There has been growing interest in the origins of musical interests and talent, explaining the recent accumulation of twin studies on these topics. It is worth noting that several twin-based conferences, such as the 2014 International Twin Congress in Budapest, Hungary and the 2017 Twins Festival in São Paulo, Brazil featured identical twin singers at their closing events. These are not isolated events — during a trip to New York City in August 2017, I attended a stunning musical performance, Songbook Summit, a four-part revue of the music of Cole Porter, Ira and Arthur Gershwin, Howard Arlen and Richard Rodgers, created by and featuring twin jazz musicians, Peter and Will Anderson. Their matched abilities, stage presence, and musical versatility (the twins seamlessly alternate between playing the clarinet and saxophone) closely match what twin studies have been revealing about musical skills, namely that both genetic and environmental influences play a role. A selective sampling of studies is presented below, followed by an interview with the Anderson twins.

Absolute pitch, or perfect pitch, is a cognitive skill, defined as the ability to correctly name any musical note that is heard, or to sing any musical note correctly without assistance (Merriam-Webster, 2017). Absolute pitch improves with training, but whether the training produces the skill or having the skill motivates one to practice has been an unanswered question. Evidence of genetic effects was found among siblings in a family aggregation study, but the possibility that unknown environmental events explained the result could not be dismissed (Baharloo et al., Reference Baharloo, Service, Risch, Gitschier and Freimer2000).

Based largely on the Baharloo et al. (Reference Baharloo, Service, Risch, Gitschier and Freimer2000) finding, Theusch and Gitschier (Reference Theusch and Gitschier2011) conducted a twin study and segregation analysis of absolute pitch. Genetic factors were indicated by the greater resemblance shown by 14 monozygotic (MZ) than 31 dizygotic (DZ) twin pairs who completed an online survey in which they answered questions about their own absolute pitch and that of their siblings. It was also concluded that absolute pitch is a complex trait, most likely affected by various environmental, epigenetic, and stochastic factors. Aside from the small sample, the results should be viewed cautiously, given that the zygosity determinations were sometimes based on twins’ self-report and number of placentae, which may be misleading.

Finnish investigators extended this work in a twin study of musical pitch and rhythm melody (Seesjärvi et al., Reference Seesjärvi, Särkämö, Vuoksimaa, Tervaniemi, Peretz and Kaprio2016). Three online musical tasks were performed by 69 MZ twin pairs and 44 DZ twin pairs, as well as 70 individual MZ twins and 88 individual DZ twins. The tasks assessed Scale (detection of pitch changes in a two-melody comparison), incongruities in Key (off key perception in a single melody), and incongruities in Rhythm (off beat perception in a single melody). The results showed that these various facets of musical ability are differently affected by genetic and environmental influences. Specifically, Scale was mostly affected by additive genetic effects (58%), Key was largely affected by shared environmental effects (61%), and Rhythm was largely affected by non-shared environmental effects (82%).

The extent to which practice contributes to musical talent has also been addressed via twin studies. Hambrick and Tucker-Drob (Reference Hambrick and Tucker-Drob2015) found evidence of genetic influence on music practice. In particular, they reported a gene × environment interaction effect in that genetic effects on musical skill were most salient among individuals who do practice. They used existing data from twins who completed a self-report survey concerning music practice and music accomplishment as part of the National Merit Twin Study (NMTS) conducted by Loehlin and Nichols (Reference Loehlin and Nichols1976). A related study included interviews with 10 Swedish MZ twin pairs discordant for music practice (Eriksson et al., Reference Eriksson, Harmat, Theorell and Ullén2017). The twins, who differed by a total of at least 1,000 practice hours, indicated various, non-systematic reasons for this difference, among them greater openness to experience by the playing twin and greater proneness to experience flow while playing. Finally, a twin study by Mosing et al. (Reference Mosing, Madison, Pedersen, Kuja-Halkola and Ullén2014), also with Swedish twins, found genetic influence on music practice (40–70% heritable), and that the extent of practice did not affect ability within MZ twin pairs.

My interview with twin jazz musicians Peter and Will Anderson was an excellent opportunity to explore some of these findings. I met up with them on September 30, 2017 at the Vibrato Grill in Beverly Glen, California, founded by jazz musician Herb Alpert, where they were scheduled to play that evening. It was just one of their stops on an extended tour throughout the United States.

The 30-year-old twins were born in Washington, D.C., but grew up in the nearby suburb of Bethesda, Maryland. Peter was born first by cesarean section with a birth weight of four and a half pounds. He was followed 10 min later by Will, the larger twin, who weighed five and a half pounds.

The twins’ father is a professor specializing in Chinese history at Georgetown University and their mother teaches English and grammar to non-native English speakers. They have an older sister who earned a degree in economics and now works for Microsoft in Seattle, Washington. Neither of the twins’ parents played a musical instrument, but a paternal aunt was a pianist and their maternal grandfather (whom they never met) was a ‘jazz fanatic’. The only direct musical influences in the twins’ home were their mother's strong appreciation for jazz, her support of their musical interests, and the availability of her recordings of favorite artists, such as Benny Goodman. The twins’ sister, who is older by 8 years, played the violin in high school when her twin brothers would have been in the elementary grades.

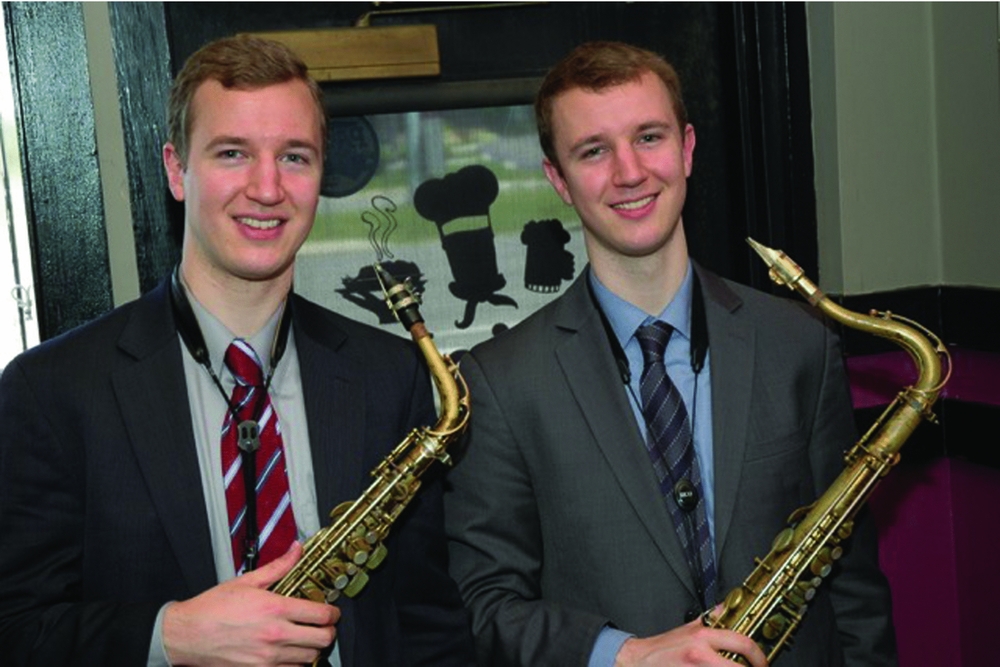

The twins’ first instrument was the clarinet. According to Peter, both he and his brother Will had always liked music and practiced constantly. Having a twin brother nearby helped to develop their musical talent because if one twin was playing video games and the other was practicing, the first brother would be motivated to practice, as well; practice is a behavior with demonstrated genetic components, as indicated above. The twins were competitive, but in a good way, just ‘trying to keep up with one another’. I have heard such sentiments before, especially from elite identical twin athletes who believe that what one of them achieves can be matched by the other (Segal, Reference Segal2000). They are usually correct. The Anderson twins eventually became adept on other instruments, such as the saxophone, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 Will (left) and Peter Anderson. Photo credit: Lynn Redmile.

In high school, the twins studied with music teacher Paul Carr, whom they credit with being an outstanding mentor. Upon graduating, they hoped to go to New York, a dream that was fulfilled when both were admitted to the prestigious Julliard School for the performing arts, located at Lincoln Center, where they completed BA and MA degrees. Throughout their years in school they were ‘great together’, with friends, teachers, and classes in common; they have never been separated for more than one month. Now they write, produce, and record music together, and believe that each brother contributes equally, although differently, to the finished product. For their production of Songbook Summit, Will completed the narration and research, while Peter was responsible for the musical arrangement. They love performing together, exuding ‘great energy’ whenever they do, and want to continue to do so in the future, perhaps overseas where appreciation for American music runs high. But in the jazz world, people often play alongside others, and while the twins do that too, they would rather be playing next to their brother.

The twins’ musical interests and talent are not their only similarities. Both describe themselves as very athletic — when they are not performing they often run in New York City, and growing up, they played soccer, basketball, and baseball and ran track. They are also both very organized, a quality that no doubt fuels their success.

However, twins are never exactly alike, and Will and Peter are no exception. Peter plays the tenor sax and Will plays the alto sax. Will has also played the flute for many years, an instrument that Peter ‘keeps in the closet’. While on tour, Will rents the cars and Peter reserves the hotels. Will is left-handed like his sister, while Peter is right-handed, and Peter is married while Will is still single. Felix Lemiere, who occasionally accompanies the brothers on guitar, observed that many people cannot tell Will and Peter apart physically, but jazz musicians can tell them apart musically. Will explained that inflection (a change in pitch or tone) can make a difference, and Peter followed up, saying that outside factors, such as hearing a particular performance or artist, can influence one's own musical rendition. I was reminded of Prof. Thomas J. Bouchard's view that identical twins are like different versions of the same song.

The Anderson twins sound a lot like MZ twins and they believe that they are — that's what their doctors have always told them — but I am not so sure. According to Will, if someone meets just one of them and comes to know them well before meeting his brother, then they have no difficulty distinguishing between them. Alternatively, if someone meets them at the same time then it becomes harder to tell them apart. Interestingly, I had a different experience — expecting the twins to be identical, as noted in their Songbook Summit biography, I was struck by their different facial structures as I watched them perform together. At our meeting at the Vibrato Grill, I asked them to complete a standard zygosity questionnaire (Nichols & Bilbro, Reference Nichols and Bilbro1966), and while it classified them as MZ at the highest level of certainty, I am not fully persuaded. The twins are interested in having their DNA analyzed using the test kit I brought with me, and the results should be available within a few weeks. The twins have admitted that they will be ‘shocked’ if they prove to be non-identical.

The Andersons offer researchers a good lesson in the best way to conduct zygosity assessments. I am reminded of Race and Sanger's (Reference Race and Sanger1975) insightful words on this topic: ‘For many years, Mr James Shields of the Genetics Unit at the Maudsley Hospital has been sending us samples of blood from the twins. We find that the blood groups practically never contradict the opinion of such a skilled observer of twins’. Despite their overall accuracy, scores on twin-typing questionnaires can be misleading in individual cases. DNA testing is, of course, the best scientific method for twin pair classification, but when it is not possible, I believe the impressions of experienced researchers count.

I have decided to give away a complimentary signed copy of my forthcoming book, Accidental Brothers, to the first reader whose judgment of the twins’ zygosity is correct, based on the photograph shown in Figure 1.

The Anderson twins’ website (http://peterandwillanderson.com) includes additional information and photographs, as well as a calendar of their upcoming performances. I want to hear them next when they perform again at the Appel Room at Lincoln Center.

Loss of a Preterm Multiple Birth Infant

In a study concerning very preterm infants, questionnaires concerning maternal mental health, parenting stress, and family functioning were completed by 162 mothers who delivered 194 very preterm infants, 65 multiples, and 129 singletons (Treyvaud et al., Reference Treyvaud, Aldana, Scratch, Ure, Pace, Doyle and Anderson2016). Fifteen mothers had experienced the loss of a newborn infant. The aim of the study was to compare anxiety and depression in the different groups of mothers at 2 years and 7 years after delivery. All participants were from the Victorian Brain Studies cohort at the Royal Women's Hospital in Melbourne, Australia.

The main findings were that maternal mental health at 2 years after delivery, and parenting stress and family functioning at 2 and 7 years after delivery did not differ between mothers of multiples and mothers of singletons. Mothers of twins and triplets actually expressed fewer depressive symptoms at the 7-year follow up. It was suspected that the higher educational levels and incomes among the multiple birth mothers helped reduce social risk factors associated with adverse symptoms and behaviors. In fact, when social risk was accounted for, the relationship between multiple birth and depression disappeared. However, the mothers who had experienced the loss of an infant were 3.6 times more likely to report high anxiety and 3.6 times more likely to report depression when their child was 7 years old.

The lack of difference between the mothers of multiple birth and singleton children should not be misconstrued. As noted by the authors, other studies have reported higher levels of depression among mothers of twins than non-twins even after controlling for social risk. In addition, according to some bereaved mothers with whom I have spoken, some individuals (including hospital staff) believe that having one surviving multiple birth child eases the loss, but mothers claim that it does not. Instead, it appears that both types of mothers experience the same high levels of grief, although selected aspects of the loss experience may differ.

Conception of Conjoined Twins

A case of conjoined thoracopagus twins (twins joined through the thorax) and sharing a heart following conception via in vitro fertilization (IVF) was reported by researchers in Lithuania (Serapinas et al., Reference Serapinas, Butkeviciene, Daugelaite, Narbekovas, Juskevicius, Bartkeviciute and Bartkeviciene2017). An eight-cell embryo with three multinuclear even-sized blastomeres was transferred and conception confirmed 5 weeks later. However, conjoined twins were identified at week 12, followed by termination of the pregnancy. A similar case was reported in Finland, which I discuss more fully elsewhere (Segal, Reference Segal2017).

The authors of this report noted that a review of the relevant literature showed that 14.8% of 75 pregnancies resulting in conjoined twins were observed in conceptions from assisted reproductive technology (ART). Given that assisted conceptions represent only 1–3% of all pregnancies, the conjoined twinning rate was clearly higher than expected. Events responsible for the association between ART and conjoined twinning are speculative, but may involve multinuclear embryos, medications, or other factors.

Depression in Fathers of Twins

Father of twins are less well studied than mothers of twins, so while the study summarized here is from 2009, it is important to consider since it raises a number of timely questions. Researchers at Case Western Reserve University examined associations among various aspects of sleep quality and deprivation and depressive symptoms in 34 fathers of twins (Flaherty & Damato, Reference Flaherty and Damato2009). The minimum gestational age of the twins was 33 weeks, and all twins were free of congenital anomalies. Data were collected three times during the first 12 weeks following delivery, by actigraphy (monitoring of how well a person is resting or sleeping by use of a device attached to the foot or wrist; see the Free Medical Dictionary, 2017) sleep diaries and by standardized instruments.

Nearly one-third of the father expressed depressive symptoms. In addition, significant correlations were found between sleep quality and fatigue, and between fatigue and depression. However, neither night sleep duration or 24-hour sleep duration related to fatigue or depression. Overall, it is clear that new fathers of twins, as well as new mothers, require professional attention to their novel parenting situation. Unanswered questions concern how family income, the availability of emotional and practical support, the presence of other children in the family, and the age of the father affect behavioral responses to raising newborn twins. The proportion of fathers who declined participation (while not reported) is also of interest, given that those who did not take part may have been too tired to do so.

Note: The research reviewed here was based on a conference abstract and a literature search failed to identify a more detailed published study. Hopefully, such a study will be forthcoming.

Twin-to-Twin Transfusion in Monochorionic-Diamniotic IVF Twins

The frequency of twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS) was compared in natural versus assisted twin conceptions by an interdisciplinary team of investigators from Israel, Spain, and Canada (Ben-Ami et al., Reference Ben-Ami, Molina, Battino, Daniel-Spiegel, Melcer, Flöck and Maymon2016). The study included 327 mothers who had delivered live monochorionic-diamniotic (MC) twins, 284 conceived spontaneously, and 43 conceived by IVF. The mean gestational age was younger for twins with TTTS (32.7 weeks) than for twins who were unaffected (35.5 weeks), but there were no differences when the groups were compared by method of conception.

Most importantly, the incidence of TTTS was lower among the IVF-MC twins (2.3%) than the non-IVF-MC twins (12.7%). The suggested reasons for this difference center around the mechanisms that could explain the MZ twinning events in the two groups. They include the increased incidence of MZ twinning linked to assisted conceptions, as well as ovarian stimulation, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and in vitro cultures. In addition, MZ twinning (as well as DZ twinning) has recently been explained by older maternal age, as has blastocyst transfer and assisted hatching (see Segal, Reference Segal2017). With IVF, an artificial break of the zona pellucida (membrane surrounding the developing ovum) could lead to division of the blastocyst (the hollow structure containing a cluster of cells called the inner cell mass from which the embryo arises; see Medicinenet.com, 2017) producing MZ twins.

High-Achieving Identical Female Twins

Prachi and Purvi Chunawala are 18-year-old identical twins from Gujarat in Western India (Yagnik, Reference Yagnik2017). The twins are noteworthy for their matched academic achievement at the highest levels. The twins obtained identical scores of 547 out of 720 on their National Eligibility Entrance Test (NEET), allowing both to be admitted to the Institute of Post-Graduate Medical Education and Research in Puducherry. Prior to that, in Class X (secondary school) one twin placed in the 99.96th percentile and the other in the 99.97th percentile, but both twins placed at the 99th percentile in Class XII (senior secondary school; class designations obtained from Wikipedia, 2017).

The twins were separately admitted to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences or AIIMS in Jodhpur and Raipur, but chose Puducherry because of its national prestige and because they could complete their education together.

Roger Federer's Two Twin Pairs

Tennis star Roger Federer is the father of two sets of identical twins (King & Burchall, Reference King and Burchall2017). His older female twins, Myal Rose, and Charlene Riva, are 7 years old and his younger male twins, Lenny and Leo, are 3. The twins watched as their father defeated the Croatian player Marin Cilic to win his eighth victory at Wimbledon. Twins are not infrequent in Federer's family — his sister has a pair of male-female twins and his maternal grandmother was a twin. Details about familial twinning in his wife Mirka's family were not provided.

Craniopagus Conjoined Twins

Conjoined twins Jaganath and Balram from India underwent a 24-hour operation for separation on July 30, 2017. This procedure was the first in a series of planned surgeries that are quite complex because the twins are joined at the head. Their chances of survival were considered minimal, but surgeons successfully separated a significant portion of their brains. The operation was led by Dr Deepak Gupta at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences or AIIMS (Basu, Reference Basu2017).

Giant Panda Twin Delivery

In Beijing, China, a giant panda named Haizi delivered twin cubs on July 30, 2017. Haizi defied the odds by giving birth to twins at the age of 23 years, equivalent to age 80 in human years. The twins are a male, weighing 123.1 grams or 4.34 ounces, and a female weighing 175 grams or 6.17 ounces. The conception and birth took place at the Wolong National Nature Reserve located in China's Sichuan province. Haizi had delivered her last pair of twins at age 19; 20 is considered the maximum breeding age for giant pandas. Interestingly, in the Chinese culture, opposite-sex twins are called ‘dragon-phoenix’ babies, a point that was raised in the article (Agence France-Presse, 2017; Chorney, Reference Chorney2017). Specifically, the phoenix is regarded as the king of all birds and in art is often paired with the dragon to symbolize harmonious marriage for a new couple. Having male-female twins is considered a blessing; hence, the name dragon-phoenix twin or long feng bao (Game Frog, 2009).