From the mid-1920s to the mid-1960s, the dance hall occupied a pivotal place in the culture of working- and lower-middle-class communities in Britain. Dancing had been enjoyed socially long before the twentieth century, but after the First World War people fell in love with it as never before. This transformation in dance culture came about through a combination of increasing prosperity and greater leisure time for large parts of the population, a relaxation of social mores concerning dress and social interaction between men and women, and transatlantic cultural developments. It began with new musical styles: ragtime, then jazz. New dances were formulated to accompany the new music and were deliberately designed for couples (most notably the foxtrot). The so-called ‘dance craze’ spread rapidly. At no time before had so many people danced so regularly and attracted so much contemporary interest and debate. Highlighting the ‘Craze for Dancing in London’ in 1919, one newspaper remarked: ‘London has gone dancing mad […] dancing establishments in London are crowded morning, noon, and night with eager pupils […] whilst dancing halls are booked up for months ahead.’Footnote 1 Newspapers outside London also reported the enormous popularity of dancing. On its growth in northern English towns in 1920, the Cheltenham Chronicle commented: ‘Dancing, with “the pictures” and football, fill in all the non-working hours in our great manufacturing towns, and, as a consequence, dancing masters not only teach the young how to step, but provide handsome dancing halls for them.’Footnote 2

By 1938 it was estimated that around 100 million admissions were made to dances every year, and the figure doubled by 1953.Footnote 3 The ‘dancing halls’ that sprung up to cater for this unprecedented demand developed into unique social spaces and a distinctive new building type of the twentieth century. Exact figures for the numbers of dance halls built are hard to come by. While the numbers of cinemas were tallied by a well-organised industry, there was no central collation of statistics regarding the dance-hall industry. However, because dance halls had to be granted music and dancing licences, renewed annually, it is possible to get some sense of their numbers from records held by local licensing authorities, together with other estimates. Each year from 1918 to 1965, between roughly 2000 and 3000 venues were licensed for regular dancing in Britain.Footnote 4 The number of venues in individual towns and cities could be correspondingly large. For example, in 1925 Liverpool had 152 places permanently licensed for dancing; in 1926 Newcastle-upon-Tyne had 99.Footnote 5 In 1935 Birmingham had 176 permanent dancing venues, and in 1937 Glasgow had 256.Footnote 6 These venues were not all purpose-built, however, and the range of buildings used was diverse. Common locations were town halls, assembly rooms and church halls, but public dances were also held frequently in swimming baths, department stores, political clubs, hotels and restaurants. In this article, a dance hall is defined as a building permanently licensed and open most days of the year to the general public, the main purpose of which was to cater for public dancing.Footnote 7 Under this definition, the number of permanent dance halls in Britain fluctuated between 400 and 500 from 1920 to 1960.Footnote 8

The dance hall's considerable importance in twentieth-century British society — its role in the growing emancipation of women, in emerging race relations and in enriching working-class social and cultural life — is only beginning to be fully recognised.Footnote 9 Although the dance hall became a significant feature in the modern urban landscape, architectural historians, too, have given the new building type very little attention. It is an odd omission, as the ‘architecture of pleasure’ has generated a growing body of scholarship. Bruce Peter, for example, has examined a broad range of building types of the 1930s, from holiday camps, cinemas and greyhound stadiums to zoos and seaside pavilions.Footnote 10 Of such building types, cinemas have received by far the most attention.Footnote 11 Hilary French's examination of spaces for dancing concentrates more on ballrooms than dance halls.Footnote 12 Addressing the gap in the literature, this article provides the first overview of dance halls from an architectural and spatial history perspective, with the aim of assisting the preservation of historic dance-hall buildings in Britain.Footnote 13

THE EVOLUTION OF A NEW BUILDING TYPE

The dance hall's emergence as a distinct social and architectural space was shaped by its varied roots in both the social world of the elite and the growing leisure industry of late nineteenth-century Britain. At one end of the social scale, it emerged from the ballrooms of large country houses, elaborate hotels, restaurants and private clubs frequented by the upper-middle and upper classes. In London, the Grafton Galleries, the Wharncliffe Rooms, the Portman Rooms, the Savoy Hotel and the Princess Galleries were popular locations for society dances before the First World War and served as models for the new building type.Footnote 14 Following the war, fashionable restaurants and hotels continued to expand their dancing facilities, as new dances from across the Atlantic captured the public imagination. Throughout the interwar period, leading dance bands were resident in elite nightspots: for example, Roy Fox at the Monseigneur Restaurant; Ambrose and his Orchestra at the Mayfair Hotel; and both Jack Hylton and the Savoy Orpheans at the Savoy Hotel.Footnote 15 These well-known dance venues (increasingly popularised by live outdoor broadcasts on the new BBC and by newspaper reports) offered inspiration for public dance halls of more diverse working-class origins. Like music halls, public dance facilities for the lower classes often began as spontaneous ‘get-togethers’ in public houses and other public places, where singing and common instruments provided music to dance to. Such spaces increasingly became formalised as publicans and entrepreneurs saw the potential profits to be gained by opening separate dancing rooms and halls in urban areas.

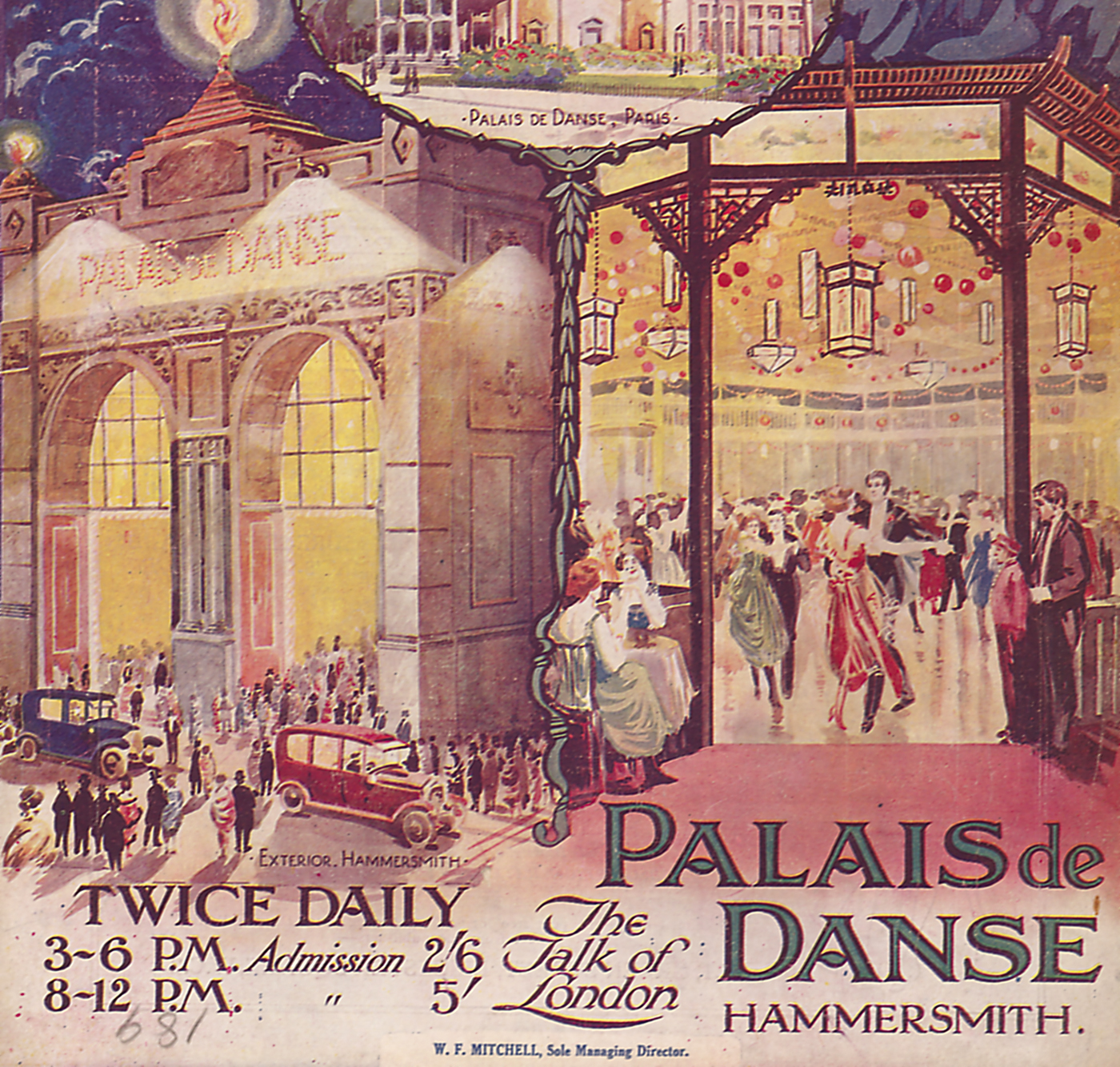

The origins of public dancing may be traced to the Victorian era and to the proliferation of new municipal halls, assembly rooms and church halls — symbols of the spirit of philanthropy and of civic pride given legislative power by the Local Government Act of 1888. The development of seaside holiday resorts, with their numerous amusement facilities, also provided the physical spaces and business experience necessary for the emergence of the dance hall. The Tower Ballroom in Blackpool, redesigned by Frank Matcham and opened in 1899, was a particularly noteworthy example.Footnote 16 Dancing was also increasingly accommodated as part of the provision of seaside pavilions, including examples as disparate as Ramsgate's Royal Victoria Pavilion, designed by S.D. Adshead and completed in 1903, and the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill-on-Sea, constructed in 1935 to the design of Erich Mendelsohn and Serge Chermayeff. Seizing on the popularity of these venues among the growing numbers of working-class holidaymakers on the coast, entrepreneurs established dance halls up and down the country. Those in the mill towns of Lancashire, for example, attempted to recreate some of the splendour of the Blackpool ballrooms.Footnote 17 Entrepreneurs were also inspired by the cavernous dance halls that had emerged in the United States before the First World War — such as the one in Pawtuxet, Rhode Island (Fig. 1) — which, designed for mass audiences, reflected the increasing leisure time and money available to large sections of the working class. Indeed, the first ‘palais de danse’ in Britain, the Hammersmith Palais, was opened in 1919 by two American businessmen (Howard Booker and Frank Mitchell) who had seen these developments at first hand.Footnote 18

Fig. 1. Postcard view of the interior of the dance hall at Pawtuxet, Rhode Island, 1911 (author's private collection)

From the 1920s to 1960, there were three main types of dance hall. There were dance halls constructed in buildings converted from other uses, purpose-built dance halls, and dance halls in multi-purpose entertainment buildings. They did not develop in a logical sequence over time, however, but responded to changing social and economic patterns.

CONVERSIONS AND THE BEGINNINGS OF THE DANCE HALL

Conversions were common not only in the early days of dance-hall construction (around 1918–23), but also in its closing days (1955–60). The popularity of dancing just after the First World War led to an initial rush by entrepreneurs and dancing masters to convert as many buildings as possible. The first requirement was sufficient uninterrupted space for a large dance floor. The floor was both one of the principal technical challenges for the architect of a dance hall and a principal attraction for customers. Accordingly, owners invested heavily in their dance floors and updated, renovated or replaced them at regular intervals. They also advertised the fact. In September 1931, the Nottingham Palais paid more than £1000 laying a new dance floor, and in October 1933 the Hammersmith Palais spent £5000 on a maple floor.Footnote 19

The installation of dance floors required consideration of several crucial issues. Especially in new buildings, which were liable to be damp on completion, room had to be left around the floor to allow the wood to swell. The width and direction of floorboards also had to be given careful thought, with some experts arguing that a floor of secret-nailed, tongue-and-groove floorboards in narrow widths gave the best effect. It was soon appreciated that boards should be laid in the direction of travel of the dancers as they progressed around the dance floor in a circular fashion. The type of timber was another major issue, as it had to be strong and durable, suitable for a high degree of polishing, but cost was also a concern. Expert opinion eventually settled on Canadian maple as the best timber for dance floors because, although expensive, it was found to be particularly hardwearing, making it ideal for the high demands that dancers would place on it. Ultimately parquet blocks, which could be arranged in multiple directions, provided the best flooring for fixed dance floors.Footnote 20

Perhaps the most important consideration in the construction of dance floors was the ability of the surface to absorb and dissipate energy. Without this, dancing could be uncomfortable and tiring and particularly wearing on the knees and ankles. Innovation led to a unique architectural feature — the sprung dance floor. One of the first to be installed in Britain was in the Tower Ballroom, Blackpool, in 1899.Footnote 21 Sprung floors made dancing less tiring and wearing, as they ‘bounced’ gently with the movement of dancers, rather than resisting them. One sprung dance-floor system that came to dominate from the 1920s onwards was the ‘Valtor’ floor, developed by Francis Morton and Company of London. The company installed floors in dance halls throughout the country, including the Grafton, Adelphi and Reece's ballrooms in Liverpool and, by the late 1930s, had installed over 400 sprung dance floors.Footnote 22 In the Valtor system, rows of light steel girders were laid under the floor, each divided into short lengths coupled together by special spring fitments. The entire floor thus rested on steel springs, with no ‘dead point’ anywhere. The floor could be adjusted to provide varying degrees of springiness, and ‘locked’ to prevent movement when not required for dancing.Footnote 23

The space above the dancers’ heads was just as important as that beneath their feet. Most ballrooms included balconies around the main dance floor where patrons could promenade and watch the proceedings below, while allowing the considerable airflow required for what could be a strenuous activity. Acoustics, an architectural science still in its infancy, was also a consideration. As a result of these requirements, large public halls, transport sheds or former factory buildings such as mills proved popular for conversion.Footnote 24 The Hammersmith Palais emerged from a former tram depot, the Carlton in Rochdale (opened in 1934) was located in a disused mill, and the Bury Palais (which opened around the same time) brought back to life a disused railway engine shed.Footnote 25

The final crucial design and technical challenge of the dance hall was the bandstand. Early dance halls featured a simple stage or raised dais to accommodate the band, but experiments were soon under way. Beginning as a practical necessity of separating the musicians from the dancers, the bandstand developed into a distinctive architectural feature. As with many other aspects of the dance-hall business, the Mecca group was at the forefront of developments, most notably introducing the revolving bandstand. One of the first was introduced at Mecca's flagship hall, the Locarno in Streatham, south London, in 1931.Footnote 26 Its purpose was twofold. First, it offered a practical solution to the problem of providing non-stop music. Previously, a change of band involved halting the dancing while equipment, instruments and players were moved on and off the stage. Alternatively, two different stages had to be constructed, which took up valuable space in the hall. With a revolving bandstand, a second band could set up in the background while the first was still performing and be brought to the audience at the press of a switch. Second, and equally important, the revolving bandstand added a highly theatrical air to the evening's proceedings, essential to create the kind of escapist atmosphere dance-hall managements were aiming for. Bandstands became highly decorative. The one at the Mayfair in Newcastle, which opened in 1961 (Fig. 2), is a good example from the dance hall's final era.Footnote 27 The tiered stage was decorated with a diamond pattern inlaid in metal against black, while the stage surround was constructed from wooden batons finished with shiny copper banding decorated with stylised stars.

Fig. 2. Bandstand at the Mayfair, Newcastle, opened in 1961 (Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums)

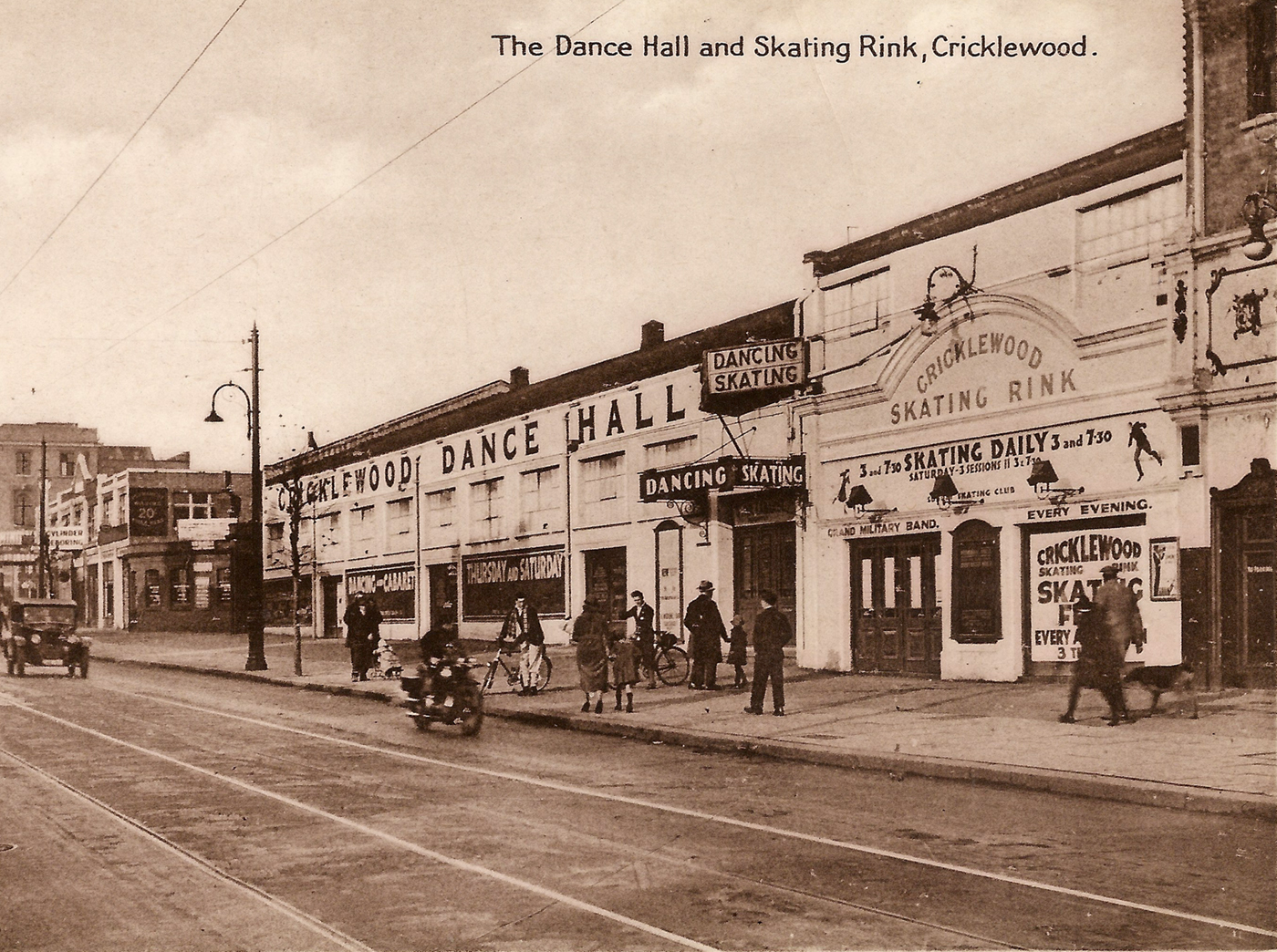

As tastes changed, dance halls took over the venues of other, declining leisure pursuits. Particularly common in the 1920s were conversions of former roller-skating rinks, which were ideal, given their large dimensions and height. The Tottenham Palais, which opened in 1925, was converted from a roller-skating rink built in 1910.Footnote 28 Sometimes the two businesses operated side by side, as in the Cricklewood dance hall and skating rink, northwest London, in the 1920s (Fig. 3). Later, in the 1950s, large numbers of redundant cinemas and theatres were converted into dance halls, as dancing outperformed both as a form of entertainment. The Majestic dance hall in Crewe, for example, was opened in 1961 by the Rank Organisation (which had diversified into dancing as cinema-going declined) following its conversion from a Gaumont cinema in a building originally erected as a picture house in 1911.Footnote 29 One of the most famous conversions from cinema to dance hall was the Rivoli Ballroom, Brockley, south London, opened in 1959.Footnote 30 The Locarno, Blackburn, was converted by the Mecca group from the former Olympia cinema at a cost of £130,000 in 1959.Footnote 31 Mecca became the largest name in dance-hall ownership and was particularly influential in the development of the building type. It was founded by Carl Heimann, who in 1927 created an offshoot of the parent firm Ye Mecca Cafés. He opened its first dance hall, Sherry's, in Brighton. By 1935, Heimann had joined forces with Alan Fairley, a Scottish entrepreneur, and by 1939 they owned nearly a dozen dance halls and controlled over 300 dance bands playing in around 2000 establishments.Footnote 32

Fig. 3. Postcard view of Cricklewood Dance Hall and Skating Rink, 1920s (author's private collection)

HAMMERSMITH PALAIS

The entrepreneurs behind Britain's first palais de danse, Booker and Mitchell, attracted an impressive £30,000 investment from shareholders, including the margarine manufacturer Sidney Van de Burgh.Footnote 33 The Hammersmith Palais was an instant success. It made over three times its original capital in the first twelve months and rapidly became known both nationally and internationally. The architect commissioned to make the conversion was Bertie Crewe (d. 1937), one of the country's leading theatre architects, who had designed over a hundred theatres, music halls and cinemas throughout Britain, including the Piccadilly and Shaftesbury theatres in London and the Palace Theatre, Manchester.Footnote 34 Booker and Mitchell's decision to employ an architect of national standing was indicative of their determination to make an architectural statement as a way of enhancing the reputation of their new venture. The site had previously been a dairy farm, then a tram depot, and finally a roller-skating rink, and on conversion could accommodate about 2500 people in its double-height space.Footnote 35 In 1921, Dancing World magazine published an illustration of its broadly classical façade and vestibule, its size exaggerated by being drawn wildly out of scale (on the left in Fig. 4).Footnote 36 The interior design (on the right) was a chinoiserie fantasy employing the contemporary fashion for ‘oriental’ motifs. The reported intention was to create an exotic escape-world that lent itself to an immersive experience for its patrons.Footnote 37

Fig. 4. Exterior and interior of the Hammersmith Palais (illustration from Dancing World, August–September 1921)

Despite Crewe's talents, the overall design of the dance hall was clearly compromised as a conversion and its former uses as a tram depot and a rink (Fig. 5). The Hammersmith Palais was essentially one large uninterrupted space, with the dance floor separated from tables and chairs around the edges. A balcony was located at one end, with a café and restaurant off the main space. Crewe's wooden framework, which served to define the dance floor and divide up the space, mimicked the architecture of a Chinese pagoda, with lacquered columns and ornamental fretwork. Above the columns was a frieze of painted glass panels depicting ‘Chinese’ scenes, and brightly coloured silk lanterns were hung around and across the dance floor. Chinese motifs were repeated throughout the dance hall, particularly in the trelliswork and painted panels that replicated oriental paper screens, backlit to enhance the artwork's colours and effects. The Chinese theme reached a climax at the centre of the dance floor, where a model mountain was created, complete with replica village and fountain. Two bandstands, one at either end of the dance floor, allowed multiple bands to play for the dancers.

Fig. 5. Postcard view of the ‘Chinese’ themed interior, Hammersmith Palais, 1921 (author's private collection)

Despite the nod to classical tradition in much of its external architecture, the Hammersmith Palais embraced modernity in its role as an important venue for the introduction of jazz to Britain. In its first nine months, it hosted the Original Dixieland Jazz Band on tour from the United States and, subsequently, other visiting American bands, notably Sidney Bechet in 1920.Footnote 38 It also attracted many of the best dance bands in Britain. The dances performed there were the height of fashion — no outdated sequence dances or polkas for Hammersmith, but foxtrots, quicksteps and the modern waltz.

The democratisation of pleasure that dance halls represented is nowhere better illustrated than in the varied social profile of the Hammersmith Palais's customers. Among its clientele were actors, sportsmen, film stars and even royalty; patrons included the Prince of Wales (a keen dancer), the Duke of York (later George VI), Lady Diana Cooper, the actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, and the celebrated French boxer George Carpentier. However, the backbone of the patronage was provided by the lower-middle and working classes — more shop girls and factory workers than celebrities, and it was estimated that three million people had danced there by 1928.Footnote 39 Despite having begun as a conversion, the Hammersmith Palais continued as a dance hall well into the post-war era and was even given an elaborate new neon frontage in the early 1960s (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Elaborate neon lighting at the Hammersmith Palais, early 1960s

PURPOSE-BUILT DANCE HALLS

As the ‘dance craze’ of the 1920s expanded, purpose-built dance halls proliferated. In Leicester, Nottingham, Manchester and other major towns and cities, entrepreneurs cashed in on the popularity of dance. Many of the businesses behind these dance halls were local consortiums made up of investors with other interests in the entertainment industry. Some were dance teachers — such as Robert Hindmarsh, who opened a string of dance halls in the northeast of England, and Malcolm Munro, who operated in Liverpool — but many had little previous experience of this emerging part of the industry.Footnote 40 Architects with established local practices were usually chosen to design the new buildings. In Liverpool, for example, the Grafton Ballroom (opened in 1924) was designed by Alfred Ernest Shennan (1888–1959), whose output in the Merseyside area included cinemas, hotels, banks and office blocks in a signature Art Deco style, together with a synagogue distinct in its Swedish-inflected functionalism.Footnote 41 The architect commissioned to design the Palais de Danse in Croydon (also built in 1924) was Hume Victor Kerr (b. 1896), whose interwar work also included the Casino Assembly Rooms in Stepney, east London, which contained a ballroom.Footnote 42 A notable survival, the Ritz dance hall built in Manchester in 1928, was an early work of the Manchester practice of Cruickshank and Seward.Footnote 43

Choosing well-established architects demonstrated the willingness of dance-hall businesses to make significant investments and helped attract publicity. The Locarno, Streatham, designed by Trehearne and Norman, Preston and Company, opened with much press interest in September 1929.Footnote 44 Advertised as ‘England's Super Dance Hall’, it cost £60,000, with £10,000 spent on the ventilation system alone.Footnote 45 Kerr's Palais de Danse in Croydon was similar in scale and ambition. The dance floor, measuring 32 × 100 ft, was overlooked by an equally impressive balcony and flanked by two orchestra stages (one on each of the long sides). It also had dedicated band rooms for the musicians. Subsidiary facilities included a large restaurant located off the main space and a café surrounding the dance floor, together with a separate ice cream soda bar.Footnote 46

Purpose-built dance halls had a confident street presence that was not always the case with conversions. The Leicester Palais (Fig. 7), designed by Clement Stretton and George Nott and opened in 1926, drew particular praise from The Builder for its elegant arcaded façade with neoclassical swag decoration.Footnote 47 The Astoria Palais de Danse in Bolton (Fig. 8), constructed at the expense of local businessman Thomas Bolton in 1928, is a striking example of how dance-hall frontages could make eye-catching statements on street corners.

Fig. 7. Exterior of the Leicester Palais, a purpose-built dance hall, 1926 (author's private collection)

Fig. 8. Handsome corner entrance to the Astoria Palais de Danse, Bolton, 1928 (Bolton News/Newsquest Photos)

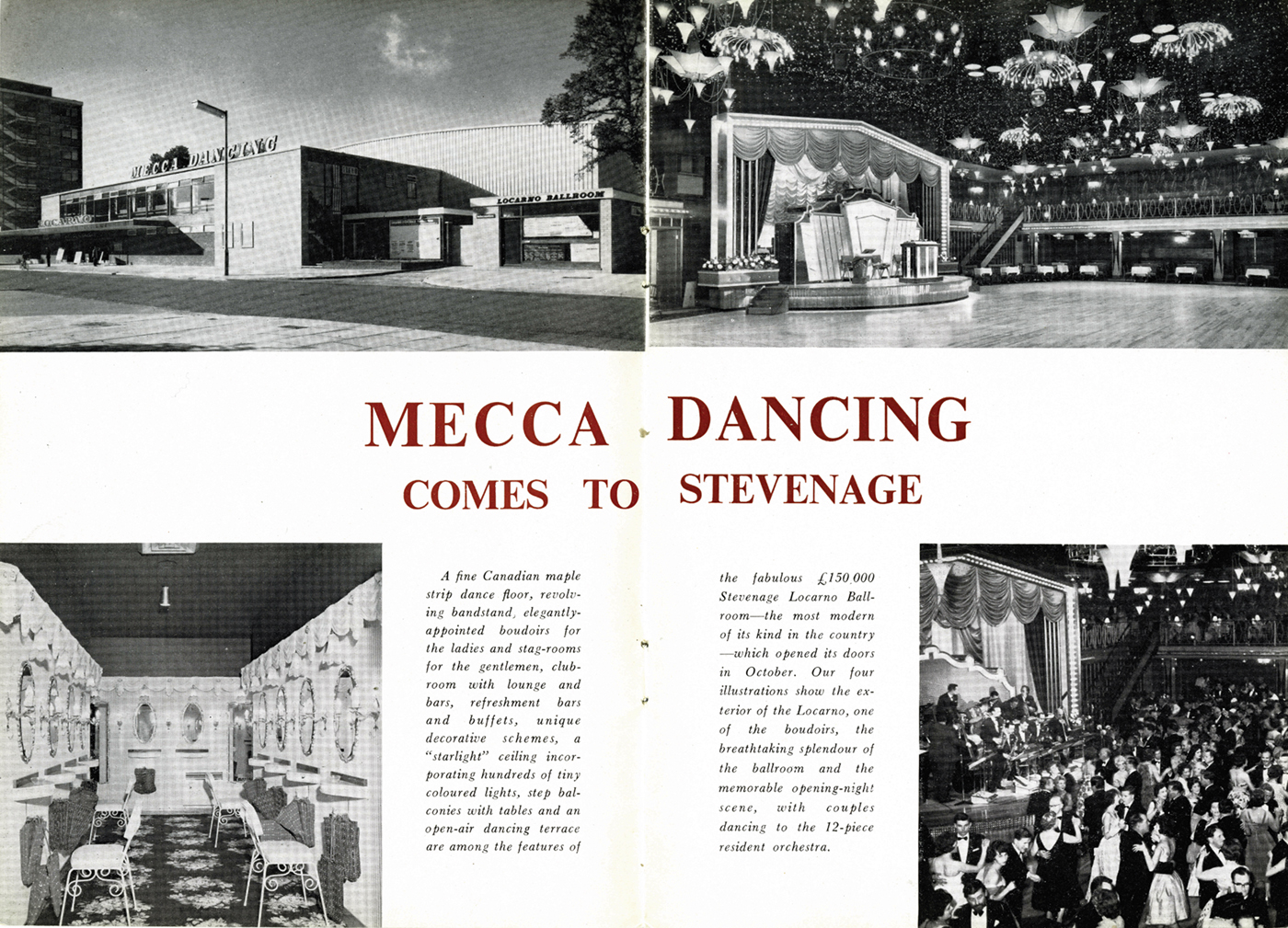

Although the construction of purpose-built dance halls declined from the 1930s, it did not end, and a second wave occurred in the late 1950s and early 1960s. In 1960, the Mecca group announced plans to invest £3 million in the industry over three years, and by 1966 it had forty-four dance halls compared to just twelve in 1951.Footnote 48 In 1961 alone, Mecca opened new purpose-built dance halls in Bradford, Newcastle upon Tyne, Hull, Basildon, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Ashton-under-Lyne and Coventry.Footnote 49 The Locarno, Bradford, which opened in September 1961, cost £550,000. The Locarno, Stevenage, which was completed the same year for a slightly more modest £150,000, was designed by Leonard Vincent, the chief architect of Stevenage Development Corporation. By this point, Mecca also employed its own group of ‘in-house’ architects for interiors, Kett and Neve, perhaps best known as the designers of one of the first motorway service stations, Trowell services on the M1 (also for Mecca).Footnote 50 The Stevenage Locarno (Fig. 9) featured a Canadian maple dance floor, a revolving bandstand, elegant ‘boudoirs’ for ladies and ‘stag rooms’ for gentlemen, a club room with lounge and bars, refreshment bars and buffets, stepped balconies with tables, an open-air dancing terrace, and a starry ceiling over the dance floor incorporating hundreds of tiny coloured lights.Footnote 51

Fig. 9. Promotional literature for the Locarno, Stevenage, 1961 (Museum Services, Stevenage, Hertfordshire)

NOTTINGHAM PALAIS DE DANSE

Opened in April 1925, the Nottingham Palais de Danse typifies the purpose-built dance hall from the height of the ‘dance craze’ in the mid-1920s. It was commissioned in 1924 by the Midland Palais de Danse Company, formed by several local entrepreneurs. Chief among them was J. Sedgewick from Derby, who had been responsible for opening the Derby Palais in 1921, a conversion of the town's Corn Exchange.Footnote 52 These businessmen had seen how lucrative dance halls had become and aimed to open one of the finest outside London. The budget was large and the quality of the building — located on a prime corner site adjacent to the city's busy central market area (Fig. 10) — was high. The architects were Thraves and Dawson.Footnote 53 Nottingham-based Alfred J. Thraves (1888–1953) became a prominent architect in the East Midlands area and designed several high-profile buildings in Nottingham, including the City Mission, although he originally made his name as a designer of chapels. Henry Holmes Dawson (1877–1964) seemingly worked with Thraves only on the palais, as he was in a London-based partnership with H.W. Allerdyce from 1920.Footnote 54

Fig. 10. Frontage of the Nottingham Palais, showing its illuminated globe, 1925 (Nottingham City Council and picturethepast.org.uk)

The principal façade was a barely resolved hybrid of modernity and tradition typical of commercial architecture of the period, a bid to be seen as both democratic and respectable. Local commentators believed that the building increased the city's status. As the Nottingham Evening Post remarked on its opening: ‘With the opening of its new Palais de Danse […] Nottingham falls in line with other progressive cities.’Footnote 55 Although the building became renowned for its large illuminated globe, the original exterior design was surmounted by a large statue of the Greek muse of dance, Terpsichore, in a typical dancing pose.Footnote 56 Terpsichore did appear on the exterior as built, but in a series of poses across a large frieze of contrasting darker stone (seen just below the globe in Figure 10). Illustrating the grace and finesse of the ‘art’ of classical dance, the frieze was likely a considered choice addressing the moral panic engendered in some parts of society by the perceived ugliness of modern social dances such as the Charleston and Black Bottom.Footnote 57

The interior of the Nottingham Palais (Fig. 11) was characterised by the eclectic deployment of neoclassical, Art Deco, oriental and even Pre-Raphaelite motifs.Footnote 58 At the centre of the dance floor was an illuminated fountain, which could rise to 12 ft, surrounded by plants. The dance floor was flanked, beneath the balcony, by two long areas of seating and tables, and a snack bar and lounge were located just off the main hall.Footnote 59 The decorative scheme in the hall included a central fresco of dancing maidens (possibly with reference to the city's local hero Robin Hood), which continued on the side walls. The lighting comprised a series of large exotic lamps in translucent glass, decorated with a mixture of Art Deco and oriental patterns to resemble stylised Chinese lanterns, supplemented by the dramatic use of changing coloured spotlights focused on the dance-floor fountain.

Fig. 11. Interior of the Nottingham Palais, 1925 (Nottingham City Council and picturethepast.org.uk)

Although dance halls were comparatively egalitarian spaces, this quality should not be overstated. People of different classes did attend the Nottingham Palais, but they did not necessarily mix. Patrons of different classes were often segregated by temporal and spatial means. In the 1920s, the class profile of the Nottingham Palais varied from day to day, as private functions closed the hall to the general public and attracted a more specialised, usually middle-class audience. Each night of the week targeted a different audience. The way in which the space was used also differed according to class. Private functions targeting the upper-middle and upper classes would be licensed to serve alcohol and food, would be granted extensions to go on for longer, and would often involve fancy dress or other special themes.Footnote 60 Public nights were never licensed (not until the 1960s) and would not usually involve fancy dress. Nonetheless, a very wide range of classes used the Nottingham Palais. In addition to its core working- and lower-middle-class patronage, it was used by upper classes from the region, and much further afield, at its various events. It was the regular venue for the South Nottinghamshire Hunt Ball, the Robin Hood Ball, the local Conservative Party Ball and various large company dances, all of which attracted local dignitaries and leading businessmen. In November 1929, the Stage Guild held its annual ball at the palais, with guests including Prince Paul of Greece.Footnote 61 A generation earlier, such events would have been held exclusively in country houses, private clubs, grand assembly rooms or private ballrooms.

DANCE HALLS AND THE MULTI-PURPOSE COMPLEX

The third and final type of dance hall was built as part of a multi-purpose complex. Experiments with multi-purpose entertainment venues had been taking place since the 1920s and 1930s and were particularly common in plans for the redevelopment of seaside resorts; hence proposals for the new Hove Pier and Amusement Centre in 1932 included a dance hall as its centrepiece.Footnote 62 Dance halls in holiday camps were also common by the 1930s, one example being at Gorleston-on-Sea in Norfolk, opened in 1937.Footnote 63 One of the first designs for a modern entertainment centre away from the coast was the Arcadium Amusement Centre proposed for the heart of London's West End, a prototype modern shopping mall and leisure centre.Footnote 64 Designed in 1934 by the architects Elcock and Sutcliffe (subsequently best known for the Daily Telegraph building on Fleet Street), it was to include three dance floors, a pool with surrounding accommodation for 600 bathers, an arcade of shops, restaurants, a ‘quick lunch bar’, brasserie and grill capable of catering for 1200 at one time. The designs also included a health centre, squash courts, gym and rooftop gardens. Only the coming of war halted the project.

More common in the interwar period — and actually constructed — were fusions between dance halls and cinemas, largely led by cinema owners afraid of dancing's threat to their business.Footnote 65 Manchester was particularly well served by these so-called ‘super cinemas’. Between 1918 and 1932, there were nearly thirty cinemas with dancing licences in the city, including the Carlton Super Cinema, the West End Cinema and the Lido Super Cinema.Footnote 66 Dance halls in more elaborate multi-purpose buildings really came into their own in the late 1950s and 1960s as part of the wave of urban redevelopment that swept through the country. Mecca was particularly forward-looking and worked hard with local planners to ensure that its dance halls were at the heart of Britain's new town and city centres, the Locarno, Coventry, discussed below, being a significant example.Footnote 67 Similar shopping-centre dance halls were opened by Mecca in Portsmouth and Basildon (where it was also called the Locarno), and Birmingham (the Mayfair). From the mid-1960s, Mecca began creating multi-purpose entertainment venues. Its Blackpool venue (Fig. 12), opened in 1965, included a Locarno, a bowling alley (run by Mecca's onetime rival Top Rank), an additional ‘modern music’ dance floor (the Highland Room), several bars, snooker halls and even a gym.Footnote 68

Fig. 12. Blackpool Locarno, one of Mecca's new multi-purpose entertainment venues, 1965 (Simon Mallett/public domain)

THE LOCARNO, COVENTRY

The Locarno, Coventry, was designed by the city architect and planning officer Arthur Ling (1913–95), together with Mecca's in-house architects Kett and Neve. Constructed in 1958–60 at a cost of £204,205, it was conceived as part of a new shopping precinct in the heart of the city (in part based on the Rows in Chester).Footnote 69 The location in a shopping precinct reflected the growing importance of consumerism in British social and economic life. In planning terms, it also reflected the thinking behind the Buchanan report on ‘Traffic in Towns’ of 1963, as the precinct was designed on the principle of separating pedestrians and cars. Smithford Way, on which the Locarno was located, was pedestrianised and multi-storey car parks were constructed close by. Ling, recognising that the removal of traffic might leave the precinct empty once the shops were closed, worked hard to keep the area alive by introducing new uses to the precinct. A dance hall and several pubs would guarantee its use after the shops had closed for the day. Ling was also concerned to bring a more ‘human’ scale to the redesign of Coventry, revising the use of large open spaces and grand vistas by the previous city planner, Donald Gibson. He achieved this by breaking up the shopping precinct's open space with an elevated circular café, with the entrance to the dance hall — a three-storey tower with an illuminated ‘Locarno’ sign — taking up the complete width of one side (Fig. 13).Footnote 70 The sense of theatricality was enhanced by the entrance to the main dance hall being reached via a glass-sided covered ‘air bridge’, two stories above ground level, which linked the tower with the main building above the shops.

Fig. 13. Postcard view of the entrance tower of the Locarno, Coventry, 1960 (author's private collection)

The façade of the main dance hall was given a canopy edged in slate to match the surrounding buildings, while the rest consisted of red and grey dark-brick panels separated with recessed blind ‘windows’ of brightly coloured glass mosaic, bordered above and below with fascias of Sicilian white marble.Footnote 71 The mosaic was the work of Fred Millett (1920–80), a mural artist with an extensive portfolio in both the public and private sectors, having worked on commissions for London County Council, Hertfordshire schools, the Post Office and National Westminster Bank.Footnote 72 The dance hall's internal illumination included strip lighting around the edge of the balcony and bandstand, interspersed with frequent use of sputnik-like spotlights in the contemporary style.

The New Bristol Centre was perhaps the zenith of these multi-purpose buildings. It was designed by Gillinson, Barnett & Partners and developed by Mecca at a cost of £2 million. Building began in the city's Frogmore Street in 1963 and was completed in 1966. The largest entertainment venue in Europe at the time, it included an ABC cinema with over 800 seats, a Locarno ballroom, a ‘Silver Blades’ ice-skating rink, a casino and several licensed bars, all served by a large multi-storey car park. Its brutalist style brought dance provision into a new architectural era.Footnote 73

DANCE HALLS: A SPATIAL HISTORY

As a new building type, the dance hall was a symbol of social, cultural and political change. Its emergence and popularity following the First World War reflected improvements in the social and economic well-being of the working and lower-middle classes. Part of a vastly expanded leisure industry whose growth was reliant on the greater availability of time and money, the dance hall depended on the spending power of the masses. Between 1914 and 1938, the average working week fell from 54 to 48 hours. Average weekly money wages rose from £1 12s. in 1913 to £3 10s. in 1938, by which time nearly 42 per cent of workers received paid holidays.Footnote 74 This gave rise to annual spending on leisure estimated at between £200 million and £250 million during the 1920s and 1930s.Footnote 75 The dance hall also arrived at the same time as mass democracy, following extensions to the franchise in 1918 and 1928 that finally gave every man and woman the right to vote. Alongside this was the growth of a highly commercialised leisure industry, which contributed to a new popular culture dominated by transatlantic trends. The dance hall, then, was part of the renegotiation of British life, culture and politics in the early twentieth century. Such changes were bringing society and culture into what John Baxendale has called the era of ‘late modernity’, in which established notions of national, class and gender identity were being challenged.Footnote 76

Dance halls opened up a whole new world of public pleasures, and thus public visibility, to the working class and to women. Dancing had a cross-class appeal and yet, by the mid-1920s, it was predominantly an activity of the working and lower-middle classes. The low cost, from 6d. up to 2s. 6d., indicates that dance organisers and commercial dance halls were aiming at a working-class audience. Virtually all the surveys of the period suggest the same. For example, the New Survey of London Life and Labour, conducted in 1928, found that

To-day dancing as an active recreation appeals to many people of all classes […] The dance-halls are within the range of nearly everybody's purse, and typists, shop assistants and factory girls rub shoulders in them […] People drop into a palais after the day's work or on Saturday evenings as casually as they go to a cinema.Footnote 77

The co-director of the Mecca chain Carl Heimann claimed that, unlike the theatre or music hall with their separate entrances and seating arrangements, dance halls were a place where class distinctions disappeared:

In the dance hall there is no differentiation between the patrons — they are all on the same ‘floor level’, all pay the same price of admission; there is no class distinction whatsoever; complete freedom of speech for all and sundry.Footnote 78

This multi-class audience for dance halls, and the democratisation it represented, was reflected in their design and even their names. The palatial references of the architecture corresponded with the term adopted for the modern dance hall, ‘palais de danse’ (literally ‘palace of dance’), which reflects the marketing strategy that made affordable luxury a key part of the attraction. During the 1920s and 1930s, advertisements emphasised the luxurious nature of the dance-hall experience. Promoting its opening night in 1925, for example, the Nottingham Palais drew attention to its ‘luxurious lounges’ with settees and ‘gold chairs’, and its ‘refinement’ in serving ‘dainty teas’.Footnote 79 Uniformed attendants, smart waiting staff and an attention to ‘service’ all added to the creation of an atmosphere previously reserved for those in higher levels of society. The colourful and ‘refined’ interior of Derby's Palais de Danse (Figs 14 and 15) demonstrates the level of glamour in leading dance halls.

Fig. 14. ‘Populist Palatial’, postcard view of the rich, colourful interior of the Palais de Danse, Derby, 1923 (author's private collection)

Fig. 15. Postcard view of ‘aristocratic’ mural paintings in the vestibule of the Palais de Danse, Derby, 1923 (author's private collection)

In the post-war period, following the shortages and restrictions of the so-called age of austerity, Britain emerged into a period of sustained and widespread prosperity. In an era of full employment and job security, real wages rose by 20 per cent between 1951 and 1959. Average weekly earnings for industrial workers grew by 34 per cent between 1955 and 1960, and by 130 per cent between 1955 and 1969. Consumerism expanded, with home ownership among manual workers reaching 40 per cent by 1962.Footnote 80 The architecture of the dance hall reflected this further democratisation of pleasure, the new centrality of the working class to national life, and a new version of ‘modernity’. The dance hall's world of luxury and escape was fully in tune with the new consumerism.

The new dance halls of the late 1950s and early 1960s were typified by sumptuous, colourful interiors along coordinated, modern lines in the ‘Contemporary’ style. Mecca's Mayfair dance hall in Newcastle, opened in 1961, is a good example (Fig. 16). The floor consisted of light grey marble-effect tiles, interspersed with a starburst design, and the walls were clad in alternate wood laminate and fabric panels, with black leatherette quilted panels, which adding a feeling of softness and luxury to the scheme. Further interest was added by the use of modern decorative geometric cornice work on the ceiling, and a series of pink, burgundy and gold downlighters.Footnote 81 Inside the main hall, the large sprung dance floor was surrounded on all sides by a seating area with burgundy carpet and tables laid with crisp white linen.Footnote 82 The room's pastel colour scheme of pinks, pale green and gold detailing was at once feminine and luxurious. The aspirational nature of the building was further reflected in the various facilities provided. There were three bars, one off the dance floor and another two upstairs (itself indicative of a less paternalistic attitude to dance halls — up to this point, magistrates had insisted they remain ‘dry’). The upstairs bars were decorated in a glamorous modern ‘members club’ style, with buttoned leather panels and copper downlighters on the walls.

Fig. 16. ‘Luxe-modern’, everyday glamour at the Mayfair dance hall, Newcastle, 1961 (Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums)

Equally impressive were the elaborate powder rooms, which included free-standing make-up stations decorated with pink candy-stripe wallpaper and topped with swags of white fabric (Fig. 17).Footnote 83 The rococo-style mirrors had lights above with tasselled fabric lampshades, and sconces in between. There were also fancy steelwork stools, and the floor was covered by a large floral carpet. Such features were not unique to Newcastle. In the Locarno, Bradford, also opened in 1961, the ‘Ladies' Boudoir’ included 45 full-length mirrors and was decorated in a ‘Georgian’ style. Its ‘Stag Room’ offered men electric shavers, hair cream and free shoeshine. Heimann had been inspired by seeing such facilities on various tours of the US during the 1940s and 1950s.Footnote 84 Similarly, in Dundee dance halls in the 1950s, automated perfume machines could be found in the women's cloakrooms, which gave a spray of Yardley's Lily of the Valley when a coin was inserted.Footnote 85

Fig. 17. ‘Ladies’ Boudoir’, Mayfair dance hall, Newcastle, 1961 (Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums)

ESCAPISM IN THE DANCE HALL

As contemporaries noted, a principal function of the dance hall was to offer an escape. According to a Mass Observation report on Bolton's dance halls in 1938,

The conclusion arrived at is that the dance hall forms a social centre which serves to insulate the individual from the unpleasant realities of everyday life. Under the soft lights and lulled by the sweet music he can sink into a dreamland of wishful desire.Footnote 86

The design of dance halls helped manufacture such dreams. In common with many entertainment venues, dance halls were sealed off from the outside world and seldom had windows. Architects enjoyed the possibilities such spaces provided. In the 1920s, borrowing from US cinema designs, ‘atmospherics’ was widely used to create escapism in the dance hall.Footnote 87 This design trend was about bringing the ‘outside’ inside, with interiors made to resemble Spanish patios or Italian villa gardens (as seen in the Spanish Hall at the Winter Gardens in Blackpool, and the Italianate lake backdrop on the main stage in the Tower Ballroom). Some dance halls themed their whole decoration, with the aim of creating a specific atmosphere. For example, at Tony's Ballroom in Birmingham, in the mid-1930s, there were two halls with sumptuous interiors on an ‘Eastern’ theme. The larger of the two, the Majestic, was decorated to represent a mosque, with prayer mats hanging from the walls and a star-painted ceiling.Footnote 88 The ‘exoticism’ continued in the names of the lounges — the Alcazar Lounge and the Baghdad Lounge. Others updated and altered their atmosphere regularly using such decorative schemes. In October 1930, the Birmingham Palais de Danse was refurbished in Japanese style, and the following year Maxime's Dance Club in Edinburgh was entirely redecorated using ‘herbaceous landscape scenes, Riviera painting and floodlighting principles’.Footnote 89

Remnants of this approach to ‘atmospherics’ could be seen in some dance halls as late as the 1950s and 1960s, despite the more functional Contemporary style taking its place. The new bandstand at the Ilford Palais in 1959 had a large painted backdrop depicting an Italianate garden, with fountains, cypress trees and urns, and three metal arches placed in front of it.Footnote 90 At the Leeds Locarno in 1964, two giant screens on either side of the bandstand projected similar images in full colour in order to evoke ‘mood’.Footnote 91 Ilford Palais even had a Tudor Room, with mock beams and accessories. Mecca's Bali Hai cocktail bars, found in many of its dance halls at this time, were full-scale escapist fantasies. The Leeds Locarno also had an Americana food bar and Flamingo coffee bar, all indicative of a popular interest in travel and the ‘exotic’.

Enhancing the escapism of the dance hall were the crucial sensory pleasures it provided. These are well conjured in the description of a Bolton dance hall in 1938:

Pausing to smooth your hair in the mirror, you go through the foyer, up more carpeted stairs. A waft of hot air, the rhythmic throb of the band, the hiss of feet on the ballroom floor assail you. Your first impression is of the red glow of the room — red walls, predominantly red carpets, orange and red lights […] The room is crowded. Facing the stairs is a lounge, with settees, wicker chairs, glass topped tables. A few couples sit out — talking […] Past them one can see heads sailing past — serenely floating (the good dancers) or bobbing jerkily (beginners). The music rises to a final chord, the drummer crashes on the cymbal […] There is a steady din of conversation.Footnote 92

Dance halls were constructed as ‘dream worlds’ where working-class men and women could be transported from the reality of their lives by vibrant colour and human interaction, liberating movement and rich, emotive music, sounds and smells. The swish of taffeta as couples progressed around the dance floor, the warm melodic sounds of a saxophone, the chatter of friends and partners, the sparkle of mirror balls, spotlights, multi-coloured lightbeams, and the faint whiff of Lily of the Valley or Midnight in Paris. The warmth and thrill of dancing cheek to cheek, waist to waist, as desire and passion ebbed and flowed at three beats to the bar, and bodies clasped together while moving gracefully, ungracefully, freed from their workaday sitting and standing, now gliding, gyrating, swaying, bending and shaking together and apart.

Dimmed lighting enhanced the power of the imagination, while coloured lights were used to create an ever-changing visual experience. For each dance, different coloured lights would be lowered — blue for a waltz, red for a foxtrot, and so on. The different colours combined with different dance moves, tempos and music to alter the mood of the dance floor. Spotlights playfully danced around the crowded floor, too. Extremely ambitious lighting schemes began to be deployed in the late 1950s, led by the Mecca group. Celestial effects were common, with thousands of bulbs creating ceilings full of sparkling ‘stars’. At the Locarno, Bradford, 35,000 Italian-made light bulbs were used on its blue painted ceiling which, when lit on their own, gave the impression of a starlit sky at night.Footnote 93

Along with these visual delights, the dance hall would immerse its patrons into an intense, vibrating world of sound. Not only the dance music, but also people talking, laughing, whispering — and of course dancing — all created a unique soundscape. Dance music was clearly a dominating feature. Virtually all dance halls, right up to their decline in the 1960s, used live music, which would continue through the evening practically non-stop. The dance programme would usually last for four hours, during which about fifty dances were played.Footnote 94 The bands were skilled at creating appealing programmes of music — varied, popular, and of the moment. The power of live music played in a relatively intimate space was such that people could literally feel the sound move through their bodies as it reverberated across the dance hall. Meanwhile, ‘sitters out’ and ‘balcony watchers’ (always a significant proportion of the dance-hall crowd) provided a constant background accompaniment with their gossip, horseplay and chatter.Footnote 95

Movement, another key sensory experience of the dance hall, was vital to the liberty and freedom it symbolised. The liberation of movement offered by the new social dances of the early twentieth century was central to their terrific popularity. Sequence dances, where everyone performed the same steps, gave way to dances formulated specifically for couples, which involved much greater physical contact between partners — the Bunny Hug and the Grizzly Bear, for example, required dancers to embrace. Using a completely new set of body movements, the dances were also far freer and open to individual interpretation.Footnote 96 The dance hall offered an outlet for ways of moving and behaving that would not be possible or acceptable outside its walls. No other public space offered the chance to display such a wide range of movement for so many people. Dancers were thrilled by the opportunity to let themselves go. Yet there was a tension between this liberation and constraint. The constraint of the crowded dance floor, for example, demanded a constant process of negotiation. Restrictions were enforced by dancing skills, or lack thereof, and the etiquette and rules laid down by the venue; and not least the pressure felt under the ever-watchful eyes of the masters of ceremonies, dance-hall staff, friends, peers, even mothers and fathers.Footnote 97

CONCLUSION

The hundreds of permanent dance halls in operation in Britain between 1918 and 1965 represented a significant expansion of the leisure industry in an age of growing mass entertainment. The buildings that enabled this new aspect of social life transported patrons into luxurious, glamorous ‘dream worlds’ of escape, and fulfilled a wide range of important social functions. Every aspect of their design was carefully considered by entrepreneurs who were often at the forefront of the newly emerging leisure industry. Dance halls provided an architecture of optimism, hope and modernity, and their style and function represented a democratisation of pleasure and the emergence of a more liberal social and political culture in Britain.

From the mid-1960s, dance halls were rapidly replaced by discos and nightclubs, or closed altogether. Many of the Mecca dance halls became bingo halls. A combination of changing musical and dance styles (recorded music replaced live, solo dances replaced couples), altered social mores (women no longer waited to be asked to dance as in the dance-hall days) and a greater range of alternative things on which to spend money (cars, holidays and housing) led to the end of the dance hall as a distinct social, cultural and architectural space.Footnote 98

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Special thanks to Dr Julian Holder whose sterling work in editing improved this piece immeasurably.