To address the systematic underrepresentation of women, more than 100 countries have adopted gender quotas in some form or another (Dahlerup et al. Reference Dahlerup, Hilal, Kalandadze and Kandawasvika-Nhundu2014). This type of electoral rule change not only poses a normative dilemma between ensuring appropriate descriptive representation of men and women and the democratic norm of having a free, unrestricted choice between candidates, it also has practical implications. While the case for gender quotas can easily be made, as they “are the most effective way in practice to achieve descriptive representation” (Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge2005, 622; see also Kittilson Reference Kittilson2005), gender quotas may also have unintended consequences. Among these unintended effects, discussions of quotas’ impact on politicians’ quality and the potential reputational costs for women elected through quotas are at the forefront of the public debate. Like the terms “token woman” and “diversity hire,” the German word Quotenfrau (quota woman) is a slur meant to discredit quota-selected women as individuals who were not selected based on their merit. Scholars have met this hypothesis of quotas’ supposed effects with a productive research agenda focusing on the causes of quota adoption (Baldez Reference Baldez2004; Gaunder Reference Gaunder2015; Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Paxton, Clayton and Zetterberg2019; Kang and Tripp Reference Kang and Tripp2018), gender quotas’ effects on public policy (e.g., Clayton and Zetterberg Reference Clayton and Zetterberg2018), and politicians themselves (e.g., Besley et al. Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017).

While most research on quotas’ effects on merit-based candidate selection does call into question the idea that quotas undermine politicians’ quality and meritocracy, these views persist in public discourse. Research shows that support for gender quotas among the public is mixed (Barker and Coffe Reference Barker and Coffe2018; Barnes and Córdova Reference Barnes and Córdova2016; Coffe and Reiser Reference Coffe and Reiser2020; Gidengil Reference Gidengil1996; Keenan and McElroy Reference Keenan and McElroy2017). Quotas are also thought to create negative stereotypes about women’s political capabilities (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008). This negativity toward quotas could be problematic for female politicians elected through quotas, as negative views about the selection mechanism—namely, quotas—could spill over to a general aversion against “quota women” (see Clayton Reference Clayton2015). I argue that the focus of the literature on the objective effects of gender quotas might have missed other subjective effects of gender quotas.

In this study, I propose classifying the effects of gender quotas as either objective or subjective. Changes in politicians’ occupational, educational, or demographic backgrounds or political performance induced by quotas can be understood as objective quota effects. Quotas’ effects on a politician’s image, the image of women in politics, their perceived performance, legitimacy, and so on, can be conceptualized as subjective quota effects. Most studies of gender quotas’ effects examine the objective effects of gender quotas. However, if quotas are perceived to undermine meritocracy or are framed in such a way, the negative impact of this perception and framing might be just as strong as if quotas would undermine meritocracy. While negative subjective effects have been theorized (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008), they rarely have been empirically tested. This study addresses this issue by empirically focusing on the subjective effects of gender quotas. Furthermore, the novel classification of quotas’ effects into objective and subjective effects allows more precise research on gender quotas in the future.

To study the subjective effects of gender quotas, I employ a vignette experiment with party elites. I ask party elites to rate a female politician based on an audio clip of an interview and an experimental vignette. In the treatment groups, I frame the female politician as someone who potentially has benefited either from a gender quota or a ceiling quota for men. Control-group respondents do not receive any information about gender quotas. By comparing the ratings of politicians framed as potentially having benefited from quotas with the ratings of politicians that were not framed this way, I can estimate the causal effect of being associated with a gender quota on a politician’s evaluation by party elites. This allows me to uncover potentially hidden biases of party elites against “quota women.”

The respondents in this experiment are party elites in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Even though the electoral laws in these countries do not feature gender quotas and pushes to introduce gender quotas into electoral laws have failed (Coffe and Reiser Reference Coffe and Reiser2020), several parties have voluntarily introduced gender quotas into their party statutes. This stresses the pivotal role of political parties, and therefore party elites, for the success or failure of gender quotas in these countries: they can decide whether to implement quotas or not, what kind of quotas to implement, and whether they are willing to comply with the spirit of the formal rules (see Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2017; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Buckley, McGing and Wright2020). I chose to study party elites as representatives of parties, as they are gatekeepers shaping the demand for women’s representation within parties (Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995). Biases of party elites against “quota women” might halt pushes for gender quotas in parties without quotas or undermine formal rules of gender quotas in parties that have introduced gender quotas. More than 1,000 party elites participated in this study.

Contrary to my theoretical expectation, framing a female politician as a person who potentially has benefited from a gender quota does not negatively impact party elites’ ratings of the politician. While this finding holds for the elites of most political parties, the elites of the populist radical right parties react to the treatments and do rate “quota women” substantially worse. This reaction is not due to the ideological and partisan cue that the quota treatment provides. While all parties’ elites perceive “quota women” as more socially liberal, only the elites of the radical right, but not the center right, evaluate quota beneficiaries worse. Even though the center right shares the radical right’s opposition to gender quotas, the radical right reacts differently to the quota treatment. Whereas the center right is opposed to quotas, the radical right is opposed to quotas and quota beneficiaries. This adds to research that shows how the radical right repoliticizes gender (Abou-Chadi, Breyer, and Gessler Reference Abou-Chadi, Breyer and Gessler2021), opposes “genderism,” and contests gender as a legitimate political identity.

Objective and Subjective Quota Effects

Generally, the literature on the effects of gender quotas studies a wide array of phenomena. To study and systematize these effects, I propose categorizing quota effects into two distinct types: objective and subjective effects.

Objective effects of gender quotas are the effects of the formal rule changes introduced by gender quotas. In general, these studies focus on how quotas affect the demographic composition of legislatures and how these changes might affect policy outputs or politicians’ competence. These effects can be direct, such as the increase in women’s descriptive representation induced by a zipper quota for party lists. However, they can also be indirect, such as quota rule changes favoring politicians of a particular background over others, for example, if female candidates replace male candidates who belong to different a social class (see Karekurve-Ramachandra and Lee Reference Karekurve-Ramachandra and Lee2020). Objective quota effects can usually be measured independently of an individual’s judgment and opinion. Most empirical research on gender quotas has focused on the objective effects of gender quotas.

In contrast with objective quota effects, subjective quota effects are linked to an individual’s perspective. They can be thought of as affecting an individual’s emotions, perceptions, attitudes, and judgments (i.e., the perceived competence, or lack thereof, of “quota women” regardless of their qualifications). These effects can also occur among direct beneficiaries of quotas. For example, these politicians might feel obliged to represent “their” gender because they were selected through gender quotas. Spillover effects of negative attitudes toward quotas to quota beneficiaries are also part of the subjective quota effects.

In the following section, I review the evidence on objective quota effects on the competence and performance of politicians. I establish that there is surprisingly little evidence for negative objective effects of quotas on politicians’ quality as measured through a variety of indicators. Subsequently, I summarize the literature on the subjective effects of gender quotas and establish that potential negative subjective effects of quotas need more scholarly attention. Lastly, I hypothesize how quotas might negatively affect the perceived quality of “quota women.”

Objective Effects of Gender Quotas

Competence of “Quota Women”

A primary concern of opponents of gender quotas is their supposed effect on the quality of politicians (Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook, Piscopo, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). By selecting politicians based on criteria other than their competence—namely, gender—quotas undermine merit-based selections and decrease politicians’ average quality. Doubting the qualifications and the competence of “quota women” is a major pattern of resistance against gender quotas (Krook Reference Krook2016). Because of the prominence of this hypothesized negative effect of quotas on candidate quality, it is not surprising that this claim has been studied extensively. In most studies, competence and qualifications are measured through educational attainment and occupational background (see Baltrunaite et al. Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014). However, studies using more complex measures of competence exist.

Besley et al. (Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017) examine the effects of introducing a zipper quota in the Swedish Social Democratic Party. The authors estimate an earnings regression and use residuals to measure competence. Politicians who, based on their characteristics, earn more than predicted are classified as competent. Politicians who make less are classified as not competent. With this measure of competence, Besley et al. find that quotas raise the average competence of politicians by increasing the average competence of male politicians. They suggest that this is mainly due to mediocre male politicians resigning.

Similar findings have been uncovered in the context of Italian local elections. Baltrunaite et al. (Reference Baltrunaite, Bello, Casarico and Profeta2014) study the introduction of gender quotas at the municipal level in Italy in the early 1990s. They find that the introduction of gender quotas increased the average education years of elected politicians by increasing the number of women elected and decreasing the number of elected men without higher education. The finding that “quota women” are not worse than non-quota politicians in terms of their capabilities and that they sometimes even raise the overall quality of elected politicians has also been shown in Britain (Allen, Cutts, and Campbell Reference Allen, Cutts and Campbell2016), Spain (Bagues and Campa Reference Bagues and Campa2017), and France (Lassébie Reference Lassébie2020).

All things considered, there is surprisingly little evidence for quotas undermining the selection of “the best” for political offices in advanced democracies. While arguments about the validity of the competence measures employed in these studies can be made, the lack of evidence for the hypothesis that quotas undermine quality using different measures is quite apparent.

Political Performance of “Quota Women”

Differences between quota and non-quota politicians might only be visible in politicians’ behavior after being elected. Hence, studies on the political performance of quota politicians also need to be reviewed to assess quotas’ quality impact. Furthermore, doubting the political performance of “quota women” is another area of resistance against gender quotas (Krook Reference Krook2016).

From an office-seeking point of view, a politician’s electoral performance is an essential component of political performance. The evidence on how well “quota women” do in elections is mixed and seems highly context dependent. In the British case, “quota women” seem to do just as well as other politicians on Election Day (Allen, Cutts, and Campbell Reference Allen, Cutts and Campbell2016). Besley et al. (Reference Besley, Folke, Persson and Rickne2017) show a positive effect of quotas on the competence of politicians in Sweden, which, in turn, is associated with electoral success. Górecki and Kukołowicz (Reference Górecki and Kukołowicz2014) contradict this finding and show that the introduction of gender quotas in Poland’s open-list proportional representation system was associated with worse electoral performance of women. Studies of the Brazilian case also show mixed associations of quotas with the electoral performance of women (Miguel Reference Miguel2008). Bagues and Campa (Reference Bagues and Campa2017), on the other hand, do not find a negative impact of quotas on votes received by the party lists most affected by gender quotas.

Another important indicator of political performance is a politicians’ long-term career advancement. Quotas might affect women’s representation in political leadership positions in later career stages when quotas no longer apply. In the Swedish case, the introduction of gender quotas among the Social Democrats improved women’s access to leadership positions and increased the number of women perceived as capable (O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016). The same can be found in Italy, where legislative gender quotas improved women’s access to leadership executive positions (De Paola, Scoppa, and Lombardo Reference De Paola, Scoppa and Lombardo2010). In France and Italy, quotas were not associated with better access to political leadership positions for women (Bagues and Campa Reference Bagues and Campa2017; Lassébie Reference Lassébie2020)

Overall, the evidence on the political performance effects of quotas and “quota women” is mixed. While few studies show adverse effects of quotas on political performance, many studies show quotas to be performance neutral. Some studies show improvements in several dimensions of political performance as a result of quotas.

Subjective Effects of Gender Quotas

While the literature on the objective effects of gender quotas in politics is quite substantial, the literature on gender quotas in politics has neglected potential (negative) subjective effects of gender quotas (Franceschet, Krook, and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Krook, Piscopo, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012). Ignoring these (side) effects of quotas could be problematic if these subjective effects undermine the perception of quota beneficiaries. While there is not much support for the hypothesis that quotas undermine merit-based selection systems, as shown in the previous section, the belief that they might undermine merit could decrease support for quotas and negatively affect quota beneficiaries.

Evidence from other fields that engage with the subjective effects of affirmative action policies hints at possible negative subjective effects of quotas in politics. In a study of Albanian public sector employees, Faniko et al. (Reference Faniko, Burckhardt, Sarrasin, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Sørensen, Iacoviello and Mayor2017) show that women hired through a quota are perceived to be more communal. This effect is especially strong among men who feel threatened in their access to decision-making positions. Furthermore, Heilman and Welle (Reference Heilman and Welle2006) show that undergraduate work group compositions based on affirmative action negatively affect competence evaluations of beneficiaries of diversity policies by other members of the group. Hiring decisions based on affirmative action policies are shown to negatively affect the perceived competence of hired personnel (Resendez Reference Resendez2002).

Within political science, the literature dealing with the subjective effects of gender quotas is substantially smaller. Some studies focus on the attitudinal effects of quotas among the general population. Gender quotas were associated with lower perceived influence of traditional leaders in Lesotho (Clayton Reference Clayton2014) and lower self-reported political engagement of women (Clayton Reference Clayton2015). Furthermore, quotas in Lesotho were associated with more gender-egalitarian attitudes among young women but not the general population (Clayton Reference Clayton2018). Other studies examining quotas’ effect in parliamentary settings show that quota beneficiaries do not necessarily suffer from marginalization and tokenism (Kerevel and Atkeson Reference Kerevel and Atkeson2013; Zetterberg Reference Zetterberg2008). However, in some cases, quota beneficiaries are less recognized in parliamentary debates (Clayton, Josefsson, and Wang Reference Clayton, Josefsson and Wang2014). Overall, there is still substantial room to study the subjective effects of gender quotas.

Potential negative subjective effects of quotas are easy to imagine. Opponents of gender quotas argue that quotas undermine merit-based selection systems. While, as established, this claim is not necessarily valid, affirmative action policies are often viewed as non-merit-based (Heilman et al. Reference Heilman, Battle, Keller and Lee1998). Beliefs about the supposed merit undermining effect of quotas in politics might affect the perception and evaluation of “quota women.” In settings outside politics, affirmative action policies have been shown to negatively affect competence perceptions of quota beneficiaries (Heilman and Welle Reference Heilman and Welle2006; Resendez Reference Resendez2002). We might observe a similar effect in a political setting. Based on individual characteristics, which shape views about affirmative action policies (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Kravitz, Mayer, Leslie and Lev-Arey2006), false beliefs about the effects of quotas, and for political gain, voters and party elites might perceive quota beneficiaries as “politicians who did not make it on their own.”

While beliefs about merit-based selection could apply in both business settings and politics, politics features distinct norms that could compound merit-based concerns. Quotas could be perceived as disruptive to the free selection of politicians, and therefore to free elections. This argument is about aversions to the selection method spilling over to the selected (see Clayton Reference Clayton2015). As opposed to other selection mechanisms that constrain the selection of politicians, such as guaranteeing regional representation, gender quotas are relatively new instruments in electoral systems, and they are still openly contested (see Krook Reference Krook2016). This might negatively affect the evaluation of “quota women.” Furthermore, quotas are usually framed as supporting women achieving equal representation, which establishes male dominance in parliaments as the norm and women in parliament as the deviation (Murray Reference Murray2014). Given these arguments, I propose the following hypothesis:

H 1 : Women elected through gender quotas are perceived as less qualified than women not elected through gender quotas.

Negative subjective effects of gender quotas on women could also manifest themselves in the career prospects of female politicians. Breaking the glass ceiling through quotas might create other glass ceilings in later career stages: it is a prominent hypothesis that quotas might trade short-term gains for long-term losses, even if the evidence points toward the opposite direction (O’Brien and Rickne Reference O’Brien and Rickne2016). If gender quotas negatively impact the perceptions and evaluations of quota beneficiaries, they might not be considered viable candidates for higher political office by party elites.

H 2 : Women elected through gender quotas are less likely to be considered for higher political office than women not elected through a gender quota.

Scholars have been aware of quotas’ potentially negative subjective effects and proposed solutions to deal with quotas’ (side) effects. Murray (Reference Murray2014) argues that as gender quotas are mainly framed as quotas for women, the burden of proof lies on the women’s side. As the “Other,” women must justify and prove their suitability for office, while men’s skills for holding office are seen as a given. Murray calls for reframing gender quotas as quotas for men. Ceiling quotas for men are thought to emphasize the overrepresentation of men rather than the underrepresentation of women (Murray Reference Murray2014). This strategy could prove successful, as perceptions and beliefs about affirmative action policies have been shown to affect support for these policies (Kravitz and Platania Reference Kravitz and Platania1993). Furthermore, the way policy details and justifications for implementing affirmative action policies are presented affects individuals’ views about these policies (Harrison et al. Reference Harrison, Kravitz, Mayer, Leslie and Lev-Arey2006). The reframing of gender quotas could lead people to adopt new problem perceptions and views about the legitimacy of quotas and their beneficiaries. Therefore, I propose the following hypothesis:

H 3 : Reframing quotas as quotas for men decreases quotas’ negative subjective effects.

Research Design

Vignette experiments were employed to test the hypothesized subjective effects of gender quotas. In the experiments, party elites were asked to evaluate real female politicians. I manipulated information on whether the politician was elected with the help of a gender quota or lack thereof. This allows me to estimate the causal effect of being associated with a gender quota on attitudes toward a politician.

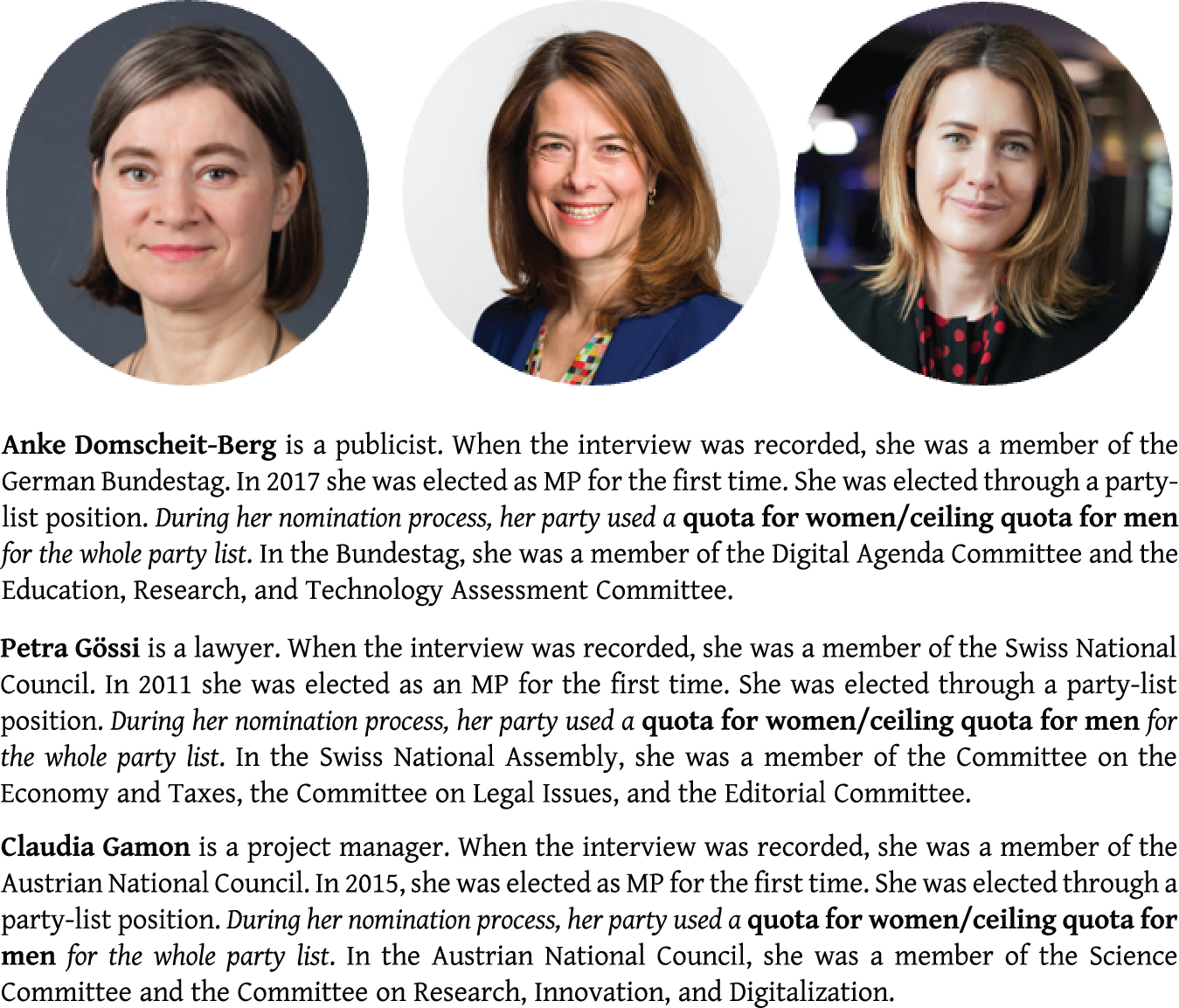

The treatments were administered through vignettes. As shown in Figure 1, the vignettes contained information on the politician’s professional background, her parliamentary committee membership, and when she was first elected to parliament. Respondents also received a picture of the politician. Most importantly, the vignettes described the nomination rules of the politician’s party. Specifically, I provided information on whether and what gender quota was employed during the politician’s nomination in a party-list-based proportional representation election. Party elites were randomly assigned to the control group and two treatment groups. The control group received the information that the politician was elected to parliament through a party-list position. Both treatment groups also received this information. Additionally, the vignette of the first treatment group contained the information that a quota for women (Frauenquote) was employed during the nomination process. In the second treatment group, I followed the argument of Murray (Reference Murray2014) and reframed gender quotas as ceiling quotas for men. This treatment group’s vignette contained the information that a ceiling quota for men (Höchstquote für Männer) was employed during the politicians’ nomination. Both treatments were used to frame the politician as a potential quota beneficiary.

Figure 1. Experimental vignettes and pictures of politicians. From left to right: Anke Domscheit-Berg (Die Linke), Petra Gössi (FDP), Claudia Gamon (NEOS). Vignettes texts are translations from the original German text. Image sources: Anke Domscheit Berg: Martin Kraft (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MJK_67671_Anke_Domscheit-Berg_(Bundestag_2020).jpg), cropped by Marco Radojevic, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode; Petra Gössi: www.parlament.ch; Claudia Gamon: OliviaBRX (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Claudia_Gamon_.jpg), cropped by Marco Radojevic, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/legalcode.

Before receiving the experimental vignettes, the party elites were asked to listen to a 90-second interview snippet by the politician. Combined with the experimental vignette, the audio clip was the basis of the evaluation process. The audio clips were chosen based on their intelligibility and left some ambiguity about the politicians’ party membership. I opted to use audio clips instead of written interview transcripts, as they contain additional information. Most importantly, by listening to the sound and tone of a woman’s voice instead of just reading the information, I could nudge respondents to think about the politician’s gender.

After listening to the audio clip and receiving the experimental vignette, party elites were asked to rate the politician based on the information they had received. Party elites had to evaluate the politician’s competence and perceived suitability for higher office. This information was recorded in a survey questionnaire on a 5-point Likert scale. Party elites were also asked to guess the ideological position of the politician. Comparing the average ratings of the politician by the treatment group with the average ratings by the control group allows me to estimate how being associated with a gender quota affects the evaluation of a politician by party elites.

The party elites surveyed for this experiment were recruited in Austria, Germany, and German-speaking Switzerland. In these countries, party elites play a pivotal role in the selection of candidates, the adoption of gender quotas, and the implementation success or failure of these measures, as the introduction of legislative gender quotas has failed so far (Coffe and Reiser Reference Coffe and Reiser2020). Therefore, each party’s elites can halt or facilitate pushes to introduce gender quotas in parties or work to undermine existing rules (see Gwiazda Reference Gwiazda2017; Mariani et al. Reference Mariani, Buckley, McGing and Wright2020).

Party elites also serve as the primary gatekeepers for women in politics and influence women’s representation within parties (Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995). Potential biases of party elites against “quota women” are arguably more problematic than voters’ biases. Only Swiss voters can influence the list positioning of parties’ nominees. Voters in Germany cannot punish individual nominees on a party list by not voting for them, and Austrian voters mainly vote for an entire party list. Therefore, studying the individuals responsible for “quota women’s” success instead of voters seems like a sensible choice.

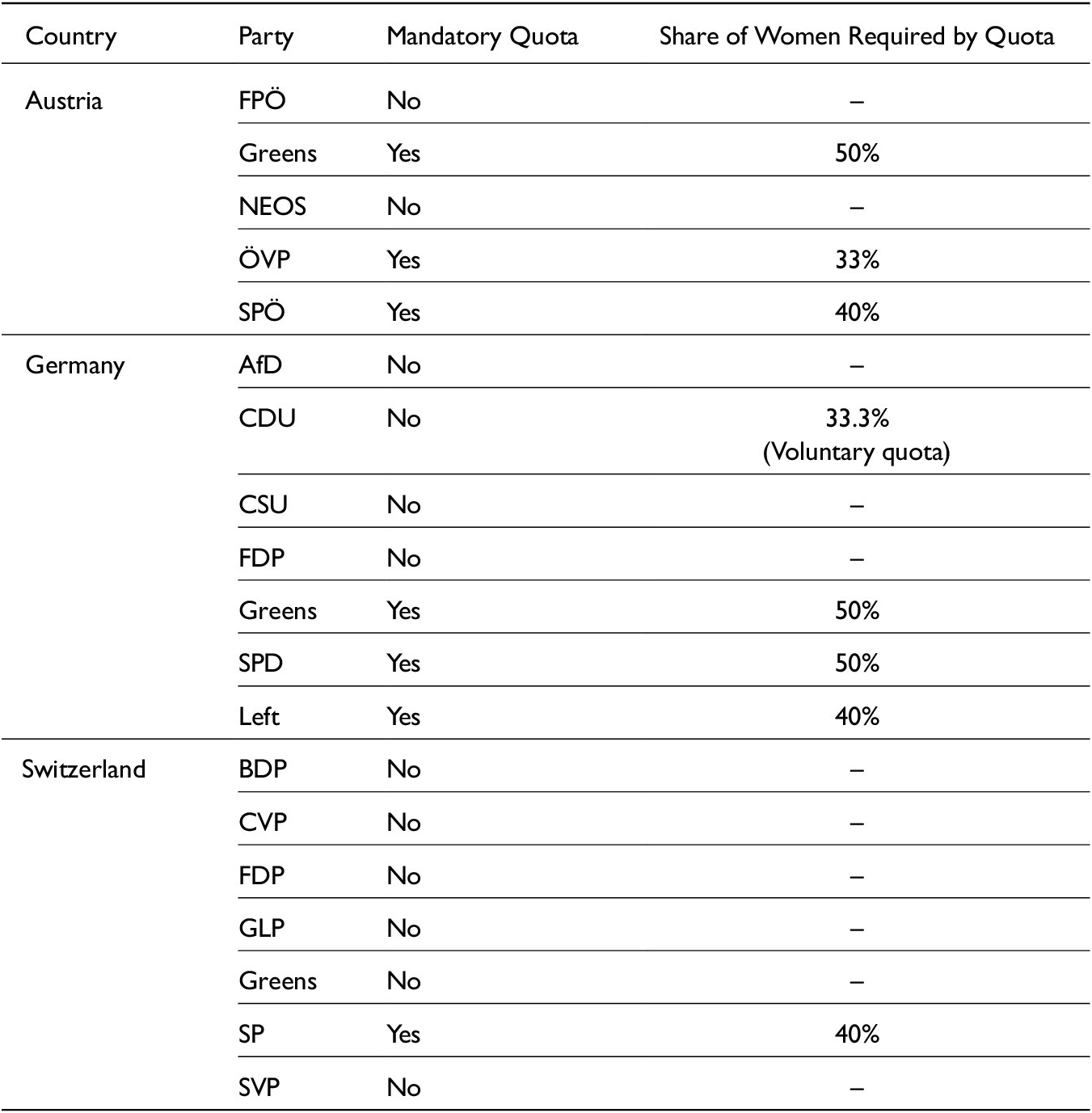

The electoral laws of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland do not feature legal gender quotas. Nevertheless, some parties have voluntarily introduced quotas to their candidate selection process (IDEA 2018). This provides me with substantial variation regarding the exposure to gender quotas between parties. As shown in Table 1, gender quotas are almost exclusively employed by left-wing parties. The ÖVP (Austrian People’s Party) is the only non-left-wing party that has introduced a mandatory quota. The share of women that the quotas require ranges from 33% to 50%. Quotas also seem to be adopted more frequently in Germany and Austria than in Switzerland. Switzerland has a more personalized electoral system, allowing voters to split their vote, rendering party-list positions less critical.

Table 1. Gender quotas in major Austrian, German and Swiss parties

Note: Party abbreviations: FPÖ = Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs; ÖVP = Österreichische Volkspartei; SPÖ = Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs; AfD = Alternative für Deutschland; CDU = Christlich Demokratische Union; CSU = Christlich-Soziale Union; FDP = Freie Demokratische Partei; SPD = Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands; Left = Die Linke; BDP = Bürgerlich-Demokratische Partei; CVP = Christlichdemokratische Volkspartei; FDP = FDP.Die Liberalen; GLP = Grünliberale Partei Schweiz; SP = Sozialdemokratische Partei der Schweiz; SVP = Schweizerische Volkspartei.

Source: Inter-Parliamentary Union, Gender Quotas Database, 2021.

As increasing women’s representation is one of the main goals of gender quotas, a look at the representation of women in these countries is merited. The share of women in the national legislatures varies: 31% in Germany, 39.3% in Austria, and 41.2% in Switzerland. Even though Switzerland introduced women’s suffrage infamously late, it can be considered a typical case of women’s representation (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2015). This, combined with the fact that the three countries share a language, makes Austria, Switzerland, and Germany compelling cases to study.

I follow a one-design, three-cases approach. This means that the basic experimental design I described was employed in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Minor alterations were made to adapt the experiment to the different cases without changing its basic logic. As I opted to ask party elites to rate a real politician, I had to minimize the chances that respondents would know the politician they were asked to rate. This was achieved by presenting them with a politician from another country. As depicted in Figure 2, Austrian elites were asked to rate a Swiss politician, German elites were asked to rate an Austrian politician, and Swiss elites were asked to rate a German politician. As Austrians, Germans, and German-speaking Swiss speak the same language, the foreign politicians they were asked to rate were perfectly intelligible for the party elites. This strategy allowed me to use real politicians and real statements, thereby ensuring the statement’s political authenticity. At the same time, it reduced the chance that respondents had prior knowledge about the politician they had to evaluate. While I cannot rule out that some respondents knew about the politician presented to them, and therefore this experimental approach has a potential source of bias, it also has substantial upsides. This experimental approach minimizes the chance that respondents feel that the experiment is artificial or not authentic. Therefore, it increases external validity. This is a sensible trade-off to make for an experiment with political elites.

Figure 2. Basic setup of experimental cases.

Austrian party elites had to rate the Swiss politician Petra Gössi. She is a member of the liberal FDP (Free Democratic Party). In the audio clip, she discussed the relationship between Switzerland and the European Union. The audio clip was 1 minute, 29 seconds long. The German politician Anke Domscheit-Berg was presented to Swiss party elites. She is a member of the Die Linke (The Left) party group in the German Bundestag. In the 1 minute, 28 second audio clip, she discussed Brexit. German party elites were asked to rate the Austrian politician Claudia Gamon. She is a member of the liberal NEOS (New Austria and Liberal Forum) party. The party elites listened to an audio clip of her discussing the European Union and its challenges. The audio clip was 1 minute, 22 seconds long.

To recruit the party elites, I contacted the party leaders at all organizational levels involved in candidate selection for the national elections: I contacted state-level leaders in Germany and Switzerland and regional, state, and national party leaders in Austria. I define party leaders as all members of the executive boards of these party chapters. The survey was administered by email. I contacted each member of the party leadership individually and invited them to participate in the survey. To contact the party elites, I initially gathered the names and email addresses of the respective party leaders in the three countries through the websites of the state-level party chapters. In total, I collected data for about 6,400 individuals: 3,000 in Austria (AT); 1,700 in German-speaking Switzerland (CH); and 1,700 in Germany (DE). Out of this group, I was able to invite 5,200 by email. I could not obtain all the names of the party leadership for every party in every state. However, I got a complete list of party leaders in more than 90% of all state-level party organizations. While the 6,400 individuals in my initial contact list are not the entire population of party elites in the three countries, the population should not exceed 6,900 individuals according to my estimates. Party elites were reminded to participate in the survey several times throughout the one-month survey period during the spring of 2020. The survey was available in German.

Overall, 1,183 elites participated in the survey, out of which about 100 failed the attention checks (see Table 6 in the appendix). The response rate was 15.4% in Germany, 16.3% in Austria, and 33.1% in Switzerland. The overall response rate was 20.9%. If we apply the experiences from legislative surveys with members of parliament to the party elites studied here, the response rates in this study are average to above average (Bailer Reference Bailer, Martin, Saalfeld and Strøm2014). Except for the Austrian cases, the respondents make up the parties’ state-level chapter executive board members.

Estimation

To test my hypotheses, I estimate the average treatment effect (ATE) of both the “woman’s quota” and the “ceiling quota” treatment in each of the three cases. I estimate a model of the following functional form:

where yi is the dependent variable. In this case, it indicates the rating of the politician by party elite i. As respondents rated the politician in several aspects, yi stands for the following dependent variables: perceived competence, perceived suitability for higher office, and perceived ideology. β1 is the estimate of the effect of the treatment variable Ti. Ti is a categorical variable that indicates whether the respondent has received no treatment, the women quota treatment, or the ceiling quota for men treatment. Finally, ε p is the error term. I estimated heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors.

To account for heterogeneous treatment effects, I also estimated the following model:

In this model, TiIi indicates the interaction between the treatment variable Ti and another variable of interest, Ii. The variables I interact the treatment with are political party and gender of the respondent. To obtain more precise estimates, I pool the data and estimate the following model:

While the treatment and the basic experimental setup are the same in all three countries, political elites were exposed to different politicians and audio clips. Furthermore, general attitudes toward quotas and female politicians might vary between cases. Therefore, I included country fixed effects in δ i. In the pooled model, I cluster the standard errors at the country level.

As response rates were not equal across sample subgroups (see Appendix 8.4 in the supplementary materials online), I employed survey weights to match the sample to known population quantities. I weighted the sample according to the party, state, and gender distribution of the contact data I have gathered and then estimated the models (see Appendix 8.6 for the unweighted analysis).

To distinguish between the true effect being unsubstantial and the estimate just being imprecise, I provide 90% confidence intervals under the estimates in each regression table. This measure makes it easier to judge whether the confidence interval around an insignificant estimate contains potentially substantial effects. I indicate whether the tail end of each confidence interval contains substantial effects by showing the number in bold if Cohen’s d is higher than .2, and I underline it if Cohen’s d is higher than .3. In Appendix 8.7, I provide summary statistics for each outcome variable.

Results: The Subjective Effects of Gender Quotas

Competence

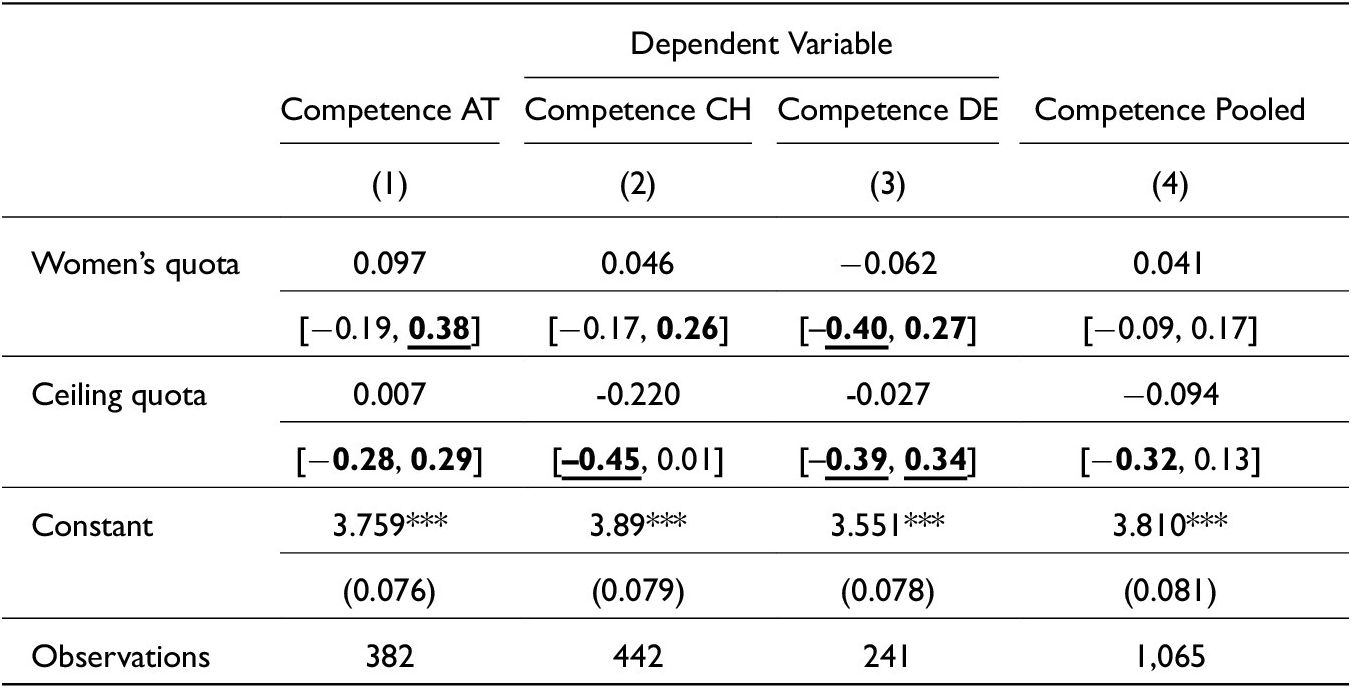

How does being associated with gender quotas affect a woman’s standing in politics among party elites? The experiment’s results for perceived competence as a dependent variable are displayed in Table 2. The first three models use only data from the individual experiments in each country to estimate ATEs. The last model pools these data to estimate the ATEs across the three experiments. The dependent variable was measured on a 1–5 scale (1 = not competent, 5 = very competent).

Table 2. ATEs of quota treatments on perceived competence

Note: 90% confidence intervals in square brackets. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (HC2) clustered on the country level for the pooled model. Estimate weighted by known population quantities. Fixed effects in the pooled model are not displayed to increase readability. Bold denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .2; underlining denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .3.

* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

In all three individual experiments and the pooled model, the effect of framing a female politician as a person who potentially has benefited from a women’s quota is close to zero and statistically not significant. The 90% confidence interval does not contain any meaningful negative values in the Austrian and Swiss experiments. Yet, it contains a small negative effect in the German experiment (effect size of approximately 5%). Overall, there is little support for H 1 , that women’s quotas negatively affect the perceived competence of female politicians substantially. Party elites do not seem to evaluate “quota women” worse if the quota is framed as a women’s quota. This certainty does not apply to the second treatment. While being associated with a ceiling quota for men does not significantly impact competence evaluations in the Austrian and German experiments, the confidence intervals are larger than in the first treatment. The Austrian, German, and pooled models contain meaningful negative estimates in the 90% confidence interval. Furthermore, in the Swiss case, the point estimate is rather substantial, and the 90% confidence interval contains negative effects up to 10%. While I do not find a significant negative effect of the ceiling quota for men treatment, I cannot rule out substantial negative effects with enough confidence.

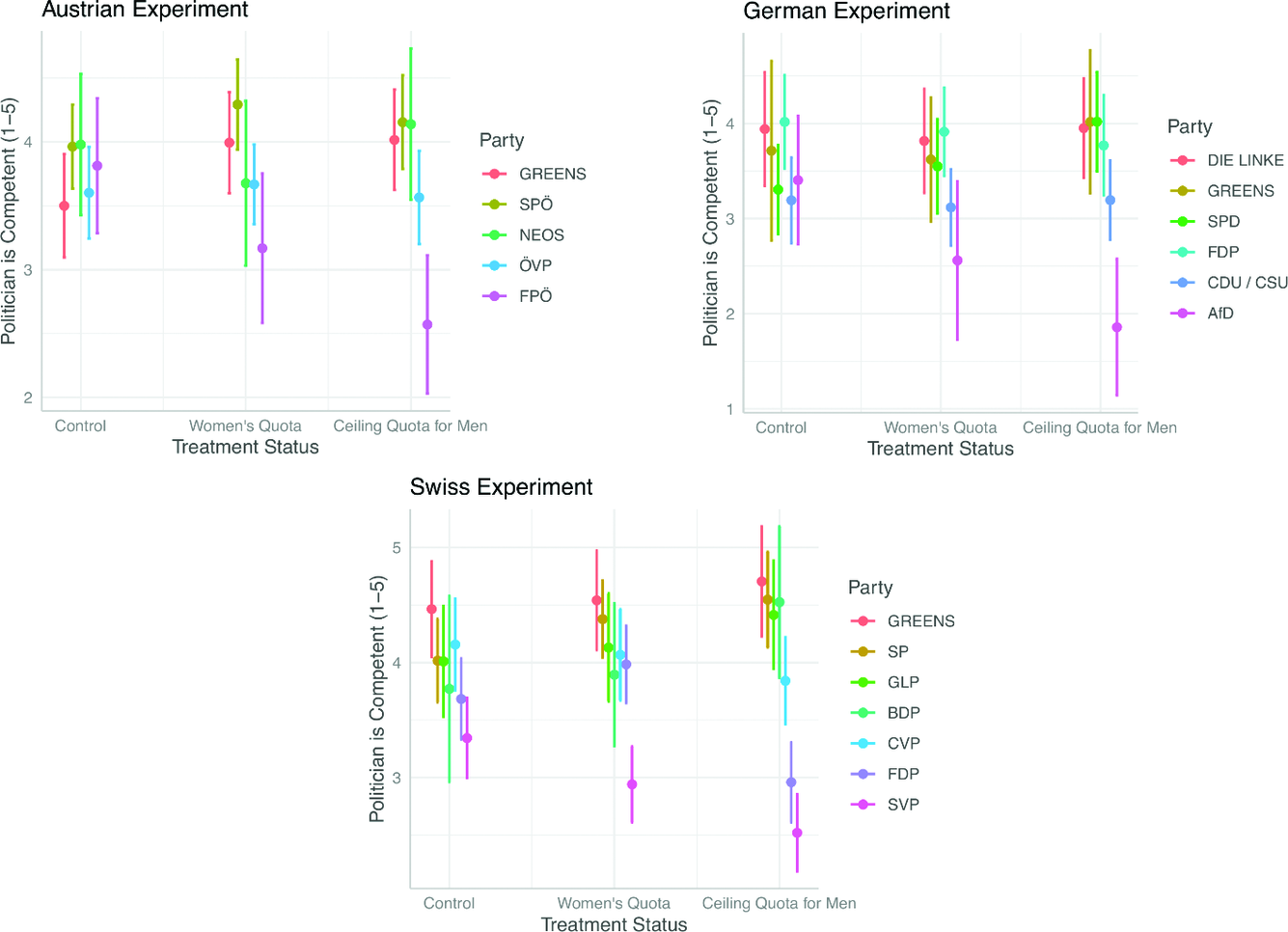

As party positions might shape views about gender quotas, I have plotted the interaction effects of the treatments and the political party of the elite in Figure 3. In these graphs, parties are ranked from left to right. This interaction was not preregistered and therefore follows a more exploratory approach. However, an interesting pattern arises in all three experiments: the variance of the competence evaluations across parties is relatively low among the control groups and increases in response to the treatments. Furthermore, most political parties in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany do not react to either quota treatment: the confidence intervals of the different experimental groups of these parties overlap, and the point estimates do not vary substantially either. This group of party elites contains elites from the far-left to center-right parties and consists of parties that have adopted gender quotas and parties that have not adopted quotas. It also includes parties with different policy positions toward gender quotas.

Figure 3. Interaction of treatment and political party of elite. Dependent variable: Perceived competence. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

However, the elites of the three right-wing populist parties, FPÖ (Freedom Party of Austria), SVP (Swiss People’s Party), and AfD (Alternative for Germany), do react to the gender quota treatments. The control-group elites of these parties do not perceive the evaluated politicians as significantly less competent than the elites of other parties. However, the right-wing populist elites who received the ceiling quota treatment assess the competence of the female politician significantly worse than the elites of other parties and the control-group elites of their party. Contrary to the predictions of H 4 , reframing gender quotas as quotas for men seems to increase rather than decrease negative responses to gender quotas. In the case of the right-wing populist elites, “ceiling quota women” are perceived to be about 20% less competent than non-quota politicians. This interaction suggests that prior beliefs about quotas might affect “quota women” perception.

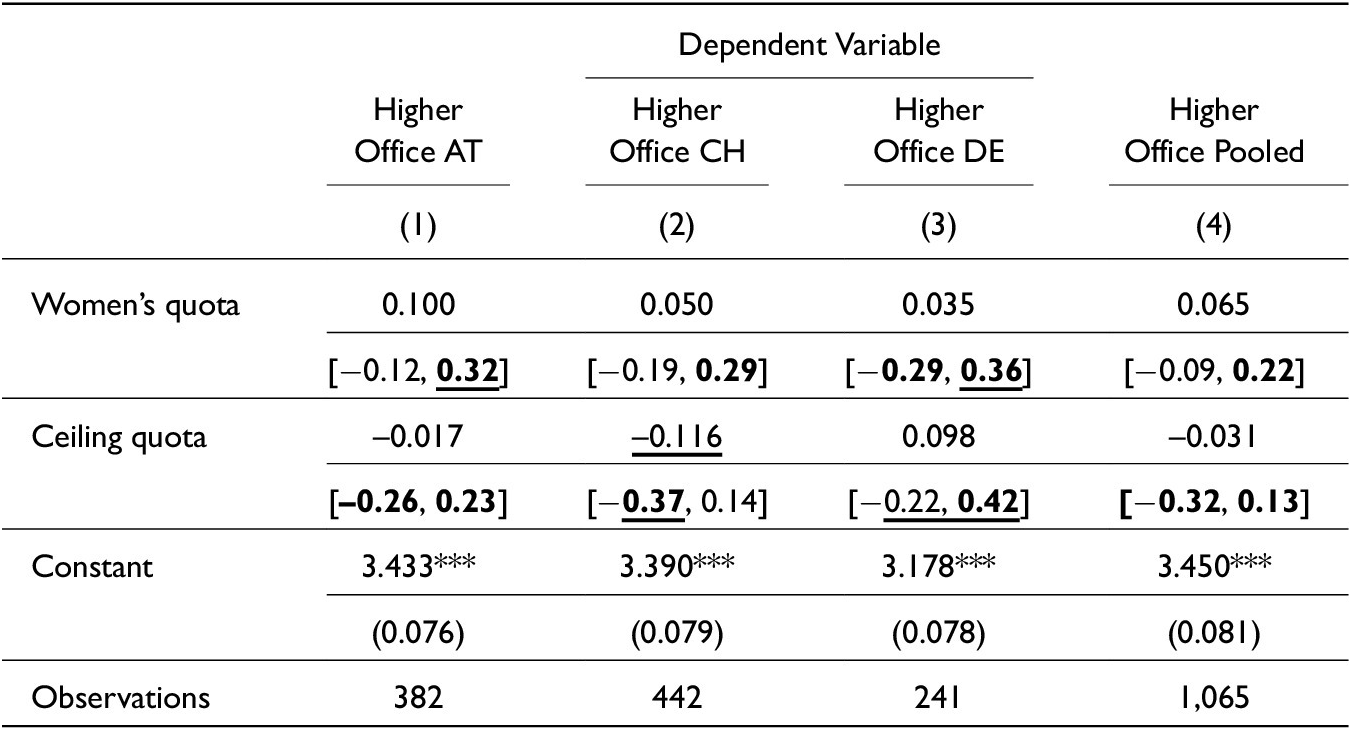

Higher Office

As hypothesized in H 2 , gender quotas could undermine quota politicians’ long-term career success. Therefore, elites were asked whether they see the evaluated politician as a suitable candidate for a higher political office. This dependent variable was also measured on a 1–5 scale (1 = not suitable for higher office, 5 = very suitable for higher office).

As seen in Table 3, the effect of being associated with a women’s quota is not significant on the politicians’ perceived suitability for higher office. Only in the German experiment does the confidence interval around the “women’s quota” estimate contain small meaningful negative values. The Swiss, Austrian, and pooled model estimates are close to zero, and the 90% confidence interval does not contain any substantial negative values. While the ceiling quota for men treatment does not significantly affect the evaluation of the politicians’ suitability for higher office, uncertainty around the estimates increases compared with the first treatment. The confidence intervals around the estimates in the Austrian, Swiss, and pooled models all contain meaningful negative effects. Therefore, I cannot rule out negative effects of being associated with a ceiling quota for men among party elites.

Table 3. ATEs of quota treatments on perceived suitability for higher office

Note: 90% confidence intervals in square brackets. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (HC2) clustered on the country level for the pooled model. Estimates weighted by known population quantities. Fixed effects in the pooled model are not displayed to increase readability. Bold denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .2; underlining denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .3.

* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

As in the last section, I combine this preregistered analysis with an exploration of party interactions. In Figure 4, I have plotted the interaction of the elites’ party and the treatment. For “suitability for higher office” as a dependent variable, the pattern that arises is similar to the party interaction effects in the competence model. The variance of responses increases in the treatment groups; in particular, the Austrian and Swiss parties of the populist radical right hold a significantly worse opinion of “quota women” than other parties’ elites. As in the competence model, this effect is more pronounced in the ceiling quota for men experimental group.

Figure 4. Interaction of treatment and political party of elite. Dependent variable: Higher office. Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

Overall, this study provides little support for the hypothesis that women’s quotas undermine the standing of women elected through them. At least among party elites, female politicians do not suffer a disadvantage in their perceived competence and suitability for higher office when associated with a women’s quota (Frauenquote). Even though voters could hold more prejudices against “quota women” than elites, they have very little direct political power over them. Only in the Swiss case are voters allowed to alter party lists and thereby punish “quota women.” Hence, this article’s politically relevant contribution is to show that party elites do not view quota women as less favorable. In particular, women benefiting or potentially benefiting from quotas can be assured that the gatekeepers in their parties do not perceive them to be worse due to quotas. I also followed the suggestions of Murray (Reference Murray2014) and reframed gender quotas as “ceiling quotas for men” (Höchstquote für Männer) and used this as a second treatment. However, this reframing effort seems to do more harm than good. While I did not find any significant negative effects associated with ceiling quotas either, I cannot rule out substantial negative effects with adequate certainty.

Exploring the interaction between party membership of the elites and the treatment offers a more nuanced picture of the effect of gender quotas and alleviates potential concerns about the treatments’ strength. While it holds that quotas do not seem to have a negative impact among most elites, the elites of the populist radical right parties stand out. The Austrian FPÖ, the Swiss SVP, and the German AfD evaluate potential quota beneficiaries substantially worse than non-quota politicians. The ceiling quota treatment causes a substantial negative reaction among these elites in particular. Even though the elites are evaluating the same audio interview, ceiling quota beneficiaries are rated up to 20% worse than non-quota politicians. The novelty of this framing might explain this strong reaction against ceiling quotas by the elites. The Höchstquote für Männer (ceiling quota for men) is not an established concept, and elites are not familiar with it, which is one potential danger of this reframing effort.

However, this explanation does not address partisan differences between the radical right and other parties. The negative reaction against ceiling quotas might also be due to this framing’s stronger emphasis on the dominant group (i.e., men). Ceiling quotas for men focus on the negative effects for the dominant group rather than women quotas’ emphasis on helping the discriminated group. While Murray (Reference Murray2014) points out that reframing quotas as “quotas for men” also entails stressing that this measure increases the quality of representation for all, this framing might also shift focus away from the benefits of quotas (increasing women’s representation) to the costs of quotas (decreasing men’s representation). This could trigger stronger negative reactions by individuals and politicians who fear losses of the dominant group, such as supporters of the radical right. This idea is even explicitly present in their manifestos. For example, the FPÖ explains its opposition to gender quotas and to “gender mainstreaming” by stating that individuals should not experience injustice based on measures that are designed to alleviate “statistically calculated inequalities” (FPÖ 2011).

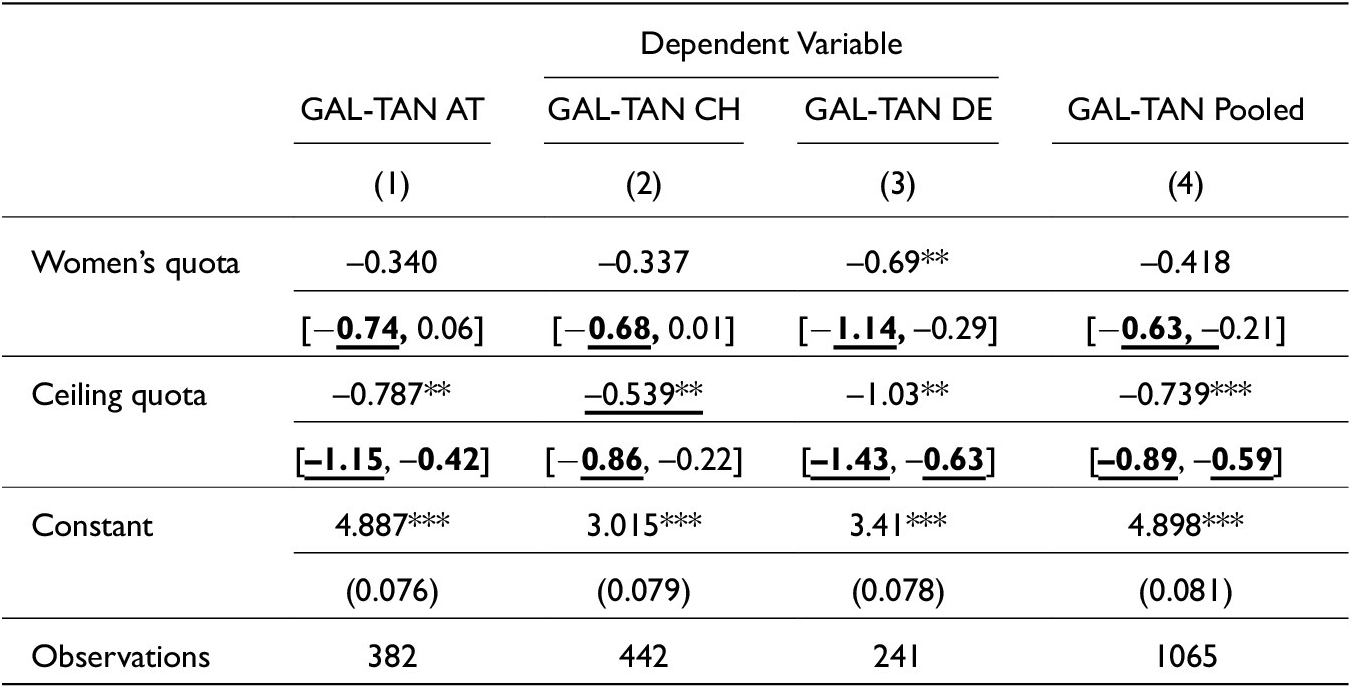

Why do elites of the populist radical right and elites of other political parties diverge in their reaction to gender quotas? One explanation can be found in Table 4. If the evaluated politicians are framed as potential women’s quota or ceiling quota beneficiaries, they are perceived as substantially more socially liberal. The ceiling quota treatment in particular causes the evaluated politician to be perceived as 0.53 (Swiss experiment), 0.79 (Austrian experiment), and 1.0 (German experiment) more socially liberal on an 11-point GAL-TAN (Green-Alternative-Libertarian/Traditional-Authoritarian-Nationalist) scale. As gender quotas are mainly used by the left and center-left parties, party elites might infer political ideology from the gender quota treatment and adjust their evaluation of the politician based on their ideological views. There is some evidence for this, as the variance of responses seems to decrease in the treatment groups (see Figure 8 in the appendix). However, this can only be part of the picture as all elites receive the quotas’ ideology cue. Still, only the elites of the populist far right seem to negatively react to quotas, while elites of the center right do not respond to them.

Table 4. ATEs of quota treatments on perceived GAL-TAN position

Note: 90% confidence intervals in square brackets. Heteroscedasticity-robust standard errors (HC2). Clustered on the country level for the pooled model. Estimates weighted by known population quantities. Fixed effects in the pooled model are not displayed to increase readability. Bold denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .2; underlining denotes that Cohen’s d is higher than .3.

* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01.

The consociational-corporatist citizenship model in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland might help solve this puzzle: in these societies, proportionality plays an important role, and therefore Krook, Lovenduski, and Squires (Reference Krook, Lovenduski and Squires2009) consider this citizenship model to be the most compatible with quotas. This might explain why the elites of most parties do not seem to hold a worse opinion of quota beneficiaries. However, Krook, Lovenduski, and Squires also point out that in these societies, the central area of conflict regarding quotas is about whether gender constitutes a valid political identity or not. While the centrist, center-right, and left-wing elites seem to accept gender as a valid political identity, the populist radical right parties are instrumental in contesting this identity and organizing anti-gender campaigns (Mayer and Sauer Reference Mayer, Sauer, Kuhar and Paternotte2017; Villa Reference Villa, Kuhar and Paternotte2017). These parties are “obsessed with gender” and politically mobilize against “gender ideology” (Dietze and Roth Reference Dietze, Roth, Dietze and Roth2020). For example, in their 2021 manifesto, the AfD opposed gender quotas not only because of merit-based concerns but also because of concerns about women’s role in society, and it proposed to “defund gender studies and gender quotas” (AfD 2021). The other parties of the radical right, the SVP and FPÖ, share this opposition toward gender quotas based on aversions against “gender politics” and “gender mainstreaming” (FPÖ 2011; SVP 2019). Furthermore, they have been involved in a push to repoliticize gender in Western Europe (Abou-Chadi, Breyer, and Gessler Reference Abou-Chadi, Breyer and Gessler2021). Therefore, the divergent reaction to the treatment might not only be due to an aversion against quotas as a selection mechanism but to opposing views on whether gender constitutes a legitimate political identity. Quotas are seen as a manifestation of “gender ideology,” “gender mainstreaming,” and “gender politics” (AfD 2021; FPÖ 2011; SVP 2019). Even though the center-right parties in these countries are usually opposed to quotas as well, they do not negatively react toward quota beneficiaries. Hence, while the center and radical right oppose quotas, only the radical right opposes quota beneficiaries.

These results also contrast with some of the findings on subjective effects of affirmative action policies outside politics, which do find negative subjective effects for affirmative action beneficiaries (Faniko et al. Reference Faniko, Burckhardt, Sarrasin, Lorenzi-Cioldi, Sørensen, Iacoviello and Mayor2017; Heilman and Welle Reference Heilman and Welle2006; Heilman et al. Reference Heilman, Battle, Keller and Lee1998; Resendez Reference Resendez2002; Zehnter and Kirchler Reference Zehnter and Kirchler2020). The stronger norm of representativeness may explain these different results in the political as opposed to the business sphere. In democracies, politicians are not only chosen based on merit but also by other factors such as regional representation or representation of language groups in a country. Even though guaranteeing representation based on gender may be contested by some political actors, guaranteeing representation as such is not alien to politics and therefore might lead to weaker adverse responses than in other settings, in which guaranteeing representation may be a foreign concept. Nevertheless, more research is needed to explain this divergence.

Conclusion

Do gender quotas hurt women in politics by stereotyping them as “quota women who are not up for the job”? In this article, I examined the gatekeepers of women’s representation: party elites. The more than 1,000 elites of German, Austrian, and Swiss parties surveyed for this study have substantial control of women’s political careers. In these three countries’ party-list-based electoral systems, they decide who gets to run on a good list position. Biases of these elites against “quota women” might undermine efforts to increase women’s representation. I asked these elites to evaluate three real female politicians based on an audio clip in a survey experiment. I experimentally manipulated whether these women had potentially benefited from gender quotas or not. This experimental setup allowed me to estimate the causal effect of being associated with a gender quota on how the party gatekeepers perceive a politician.

While I find little support for the idea that “quota women” are regarded as less competent or unsuitable for higher office, this relationship gets more intersting once I take party membership of the elites into account. The elites of most parties in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland do not discriminate against quota beneficiaries. However, the elites of the populist radical right parties do. Just changing the information on whether a politician potentially has benefited from a gender quota caused these elites to perceive said politician as less competent and less suitable for higher office.

Reframing gender quotas as “quotas for men” (Murray Reference Murray2014) does, if anything, hurt rather than help quota beneficiaries. This does not necessarily mean that this reframing effort is in vain, but that there is a danger involved, namely, triggering adverse reactions by stressing the costs for the dominant group rather than the benefits for the discriminated. Further studies could explicitly highlight the benefits of “quotas for men” and see whether this triggers more positive subjective effects.

Even though “quota women” are perceived as more socially liberal than “non-quota women,” this cannot explain the divergence between the elites of the populist radical right and other parties. While the center right also opposes left-wing policies and especially gender quotas, they do not react negatively toward quota beneficiaries. The negative attitude toward quotas by the center right does not spill over to quota beneficiaries, whereas it does so among the radical right. Therefore, the negativity toward quota beneficiaries by the radical right might not be a mere opposition to specific quota policies but more far-reaching. In line with Krook, Lovenduski, and Squires (Reference Krook, Lovenduski and Squires2009), I argue that while quotas are compatible with the citizenship model of Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, gender as a legitimate political identity is contested by the parties of the populist radical right. The aversion against “quota women” by the elites of the populist radical right might therefore be driven not only by the opposition against quotas but also by the opposition against gender as a political identity. This is in line with other research that shows increasing “anti-genderism” among the populist radical right.

Furthermore, I suggest being more conceptually fine-grained when examining the effects of gender quotas. I propose to distinguish objective and subjective quota effects. Here, I provide a study of the subjective effects of quotas. Future studies of the subjective effects of gender quotas need to consider how the attitudes toward the groups benefiting from quotas shape views about quotas. Negative attitudes toward “quota women” could manifest in other ways, such as stereotyping. Moreover, quotas may only be used as a quality heuristic in low-information environments. The elites in this experiment were given detailed information about the politicians and actual statements by the politicians. In this high-information environment, quotas may not be needed as a heuristic to judge a politician. Furthermore, newly elected, low-profile, or young politicians might suffer negative subjective effects from quotas. Their status as quota-elected politicians may be more defining for them than for more experienced politicians. Future studies should explore the negative subjective effects of quotas in low-information environments.

Nevertheless, this study adds to a wealth of research showing that quotas may be better than their reputation in Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. This is not to say that quotas have no downsides (see Jensenius Reference Jensenius2016; Karekurve-Ramachandra and Lee Reference Karekurve-Ramachandra and Lee2020), but instead that the publicly debated downsides stand on dubious empirical ground. Considering this evidence, the prevalent arguments about the capabilities and perception of women selected through quotas seem ideologically motivated.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000137.