Why mental health matters, especially in conflict-affected settings: a situational analysis of Somalia

Global perspective

Globally, mental, neurological and substance use disorders affect about 10% of the general population, but in countries affected by humanitarian crises, one in every five people is estimated to suffer from some form of mental disorder (Marquez, Reference Marquez2018; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Bauer, Endale, Qureshi, Doukani, Cerga-Pashoja, Brar, Eaton and Bass2021). More than 75% of people with mental, neurological and substance use conditions in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), especially in conflict and post-conflict settings, do not have access to effective mental health services (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Bauer, Endale, Qureshi, Doukani, Cerga-Pashoja, Brar, Eaton and Bass2021). The lack of treatment increases the burden of illness in terms of mortality, morbidity, stigma and discrimination (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Bauer, Endale, Qureshi, Doukani, Cerga-Pashoja, Brar, Eaton and Bass2021). Evidence shows that mental illness is a leading cause of disability globally (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016).

Economically, mental disorders lead to reduced productivity, unemployment, loss of wages and resultant poverty, which affects the financial well-being at the individual level and eventually at the national and global levels (Marquez, Reference Marquez2018; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Bauer, Endale, Qureshi, Doukani, Cerga-Pashoja, Brar, Eaton and Bass2021, Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016). Depression and anxiety alone cost the global economy about a trillion US dollars a year, while the total financial cost of mental illness is expected to exceed US$ 6 trillion by 2030 (WHO, 2016). LMIC bear more than 50% of these costs (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016). Despite the enormous financial consequences of mental health, tackling mental illness is still less of a priority in LMIC, with most such countries allocating <2% of their health budget to mental health services (Marquez, Reference Marquez2018, Vigo et al., Reference Vigo, Thornicroft and Atun2016).

In 2016, the World Bank (Kovacevic, Reference Kovacevic2021), International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Health Organization (WHO) and global partners reiterated that returns on investment on treatments for mental health far outweigh the cost. A 2016 cost–benefit analysis of investing in mental health treatment for depression and anxiety in 36 low/middle- and high-income countries for the 15 years from 2016 to 2030 concluded that there would be a fourfold return on investment for every dollar spent (Chisholm et al., Reference Chisholm, Sweeny, Sheehan, Rasmussen, Smit, Cuijpers and Saxena2016).

The Somali context

Three decades of conflict and violence in Somalia have led to economic marginalization and social exclusion of young people in Somalia, who make up about 70% of the population, as well as other vulnerable people such as women and children and internally displaced people. These factors drive poverty and the resultant health inequity in the country. In Somalia, it is estimated that the prevalence of mental health illness is much higher than global estimates with one in every three people affected by some form of mental illness (Abdillahi et al., Reference Abdillahi, Ismail and Singh2020). Years of conflict and the effects of climate shocks have contributed to widespread psychosocial trauma and social deprivation in Somalia with devastating consequences on people's mental health (Abdillahi et al., Reference Abdillahi, Ismail and Singh2020). Although the burden of disease in Somalia (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020a) is dominated by communicable diseases, maternal, neonatal and nutritional disorders which represent 68% of disability-adjusted life years, mental disorders constitute a significant burden of disease as it tops at the 13th most disabling condition as calculated by years lived with disabilities (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020b).

The conflict and instability in Somalia, climate shocks and the recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic have delivered a triple blow to the country, substantially increasing the need for mental health and psychosocial support. The country's mental health services are almost non-existent with just 0.5 psychiatric beds/100 000 population compared to 6.4 beds/100 000 in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region and 24 beds/100 000 globally (WHO, 2019). With the exception of a few understaffed and poorly resourced psychiatric hospitals, Somalia has no community-based mental health services.

Given the country's current situation with the health workforce, it is unlikely that Somalia will be able to train enough mental health specialists in the foreseeable future. Therefore, it is prudent, realistic and strategic to adopt a task-shifting model (WHO, 2007) in which non-specialists provide mental health services integrated within primary health care using the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (WHO, 2008a, 2008b).

Scaling up integrated community mental health services through task-sharing

The health sector in Somalia has embarked on the implementation of a transformative agenda aimed at rebuilding and reorganizing its health system to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) using primary health care services as the entry point. The government is expected to roll out soon an essential package of health services (EPHS) with an integrated service delivery model with primary health care at its heart. The package is a set of cost-effective and evidence-informed interventions to be delivered across all service platforms in the country. This package will bring the health services close to families, ensure a continuum of care across all service delivery platforms and improve access and coverage.

Against the backdrop of the roll out of the EPHS, and with the great demand for mental health services, the treatment gap and unmet needs must be strategically tackled. This can be done through a task-shifting model which strengthens and uses the existing health infrastructure and workforce, and increases community outreach and support by enlisting more community health workers including the newly launched female health workers or Marwo Caafimad in the Somali language. The Marwo Caafimad programme was jointly developed by the federal ministry of health, UNFPA, WHO and UNICEF in an attempt to address the huge gap in health human response, especially with the understanding of the high rates of maternal and infant mortality in the country (MoH, 2014). The Marwo Caafimad programme is seen as cost-effective, culturally appropriate and sustainable interventions to address the huge gap in primary health care in the country and enhancing integrated health service delivery (MoH, 2014). Therefore, the Mental Health & Psychosocial Services (MHPSS) task shifting through community-based integrated health services is consistent with the government's strategies for achieving UHC (2019–2023) and the implementation plan for the EPHS (MoH, 2021).

Although no evidence shows the effectiveness of this new Marwo Caafimad model, the existing political and structural support system for integrating community health workers in the healthcare system in Somalia could be an ingredient for success and overcome the systemic challenges often faced by LMIC countries in implementing task-shifting model (Javadi et al., Reference Javadi, Feldhaus, Mancuso and Ghaffar2017)

COVID-19 and its mental health consequences

A worldwide global survey undertaken by WHO looking into the impact of COVID on mental health services (2020). With a response rate of 67% (130 countries), the result showed that 93% of all the countries reported disruption of one or more of mental health services during the pandemic (WHO, 2020). The mental health services hard hit during the lockdowns were community mental health services, residential care and addiction treatment programmes. While public mental health programmes such as school mental health programmes, older adults, youth services and antenatal and postnatal mental health services were significantly disrupted (2020). These are essential mental health services at the most critical time for the most vulnerable sectors of the society (2020).

Somalia and the rest of the Eastern Mediterranean Region of WHO comprising of 21 countries across Horn of Africa (Somalia and Djibouti), North Africa, Middle East, South Asia (Pakistan and Afghanistan) with a population of nearly 700 million host half of all the 70 million displaced population in the world (Said et al., Reference Said, Lopes, Lorettu, Farina, Napodano, Amadori, Pichierri, Cegolon, Padrini, Bellizzi and Alzoubi2021). With high rates of mental health conditions in humanitarian settings, the current global pandemic is making such scenario even worse, where pandemic-related conditions are leading to psychological distress, anxiety and depression. While at the same access to already limited mental health services and supplies disrupted due to the shutdowns especially lifesaving drugs for psychosis, depression and epilepsy (Said et al., Reference Said, Lopes, Lorettu, Farina, Napodano, Amadori, Pichierri, Cegolon, Padrini, Bellizzi and Alzoubi2021).

There is a significant dearth of research and publication on the mental health impact of COVID in the context of Somalia however, existing studies from similar humanitarian settings indicates a significant increase of COVID-related mental health conditions. For example, reports showed an increase in suicide and suicide attempts and domestic and gender-based sexual violence among refugees in Lebanon and Jordan (Said et al., Reference Said, Lopes, Lorettu, Farina, Napodano, Amadori, Pichierri, Cegolon, Padrini, Bellizzi and Alzoubi2021).

Resource-limited countries such as Somalia are the least likely capable of addressing the serious challenges posed by a pandemic of such magnitude. The healthcare system in Somalia has never developed beyond providing the most basic functions and has negligible capacity to the level of mental health conditions facing its citizens. It is within the current pandemic situation that it becomes more urgent to introduce robust task shifting in mental health and psychosocial support service provision to addressing existing and COVID-19-related challenges.

WHO's pyramid framework for mental health services

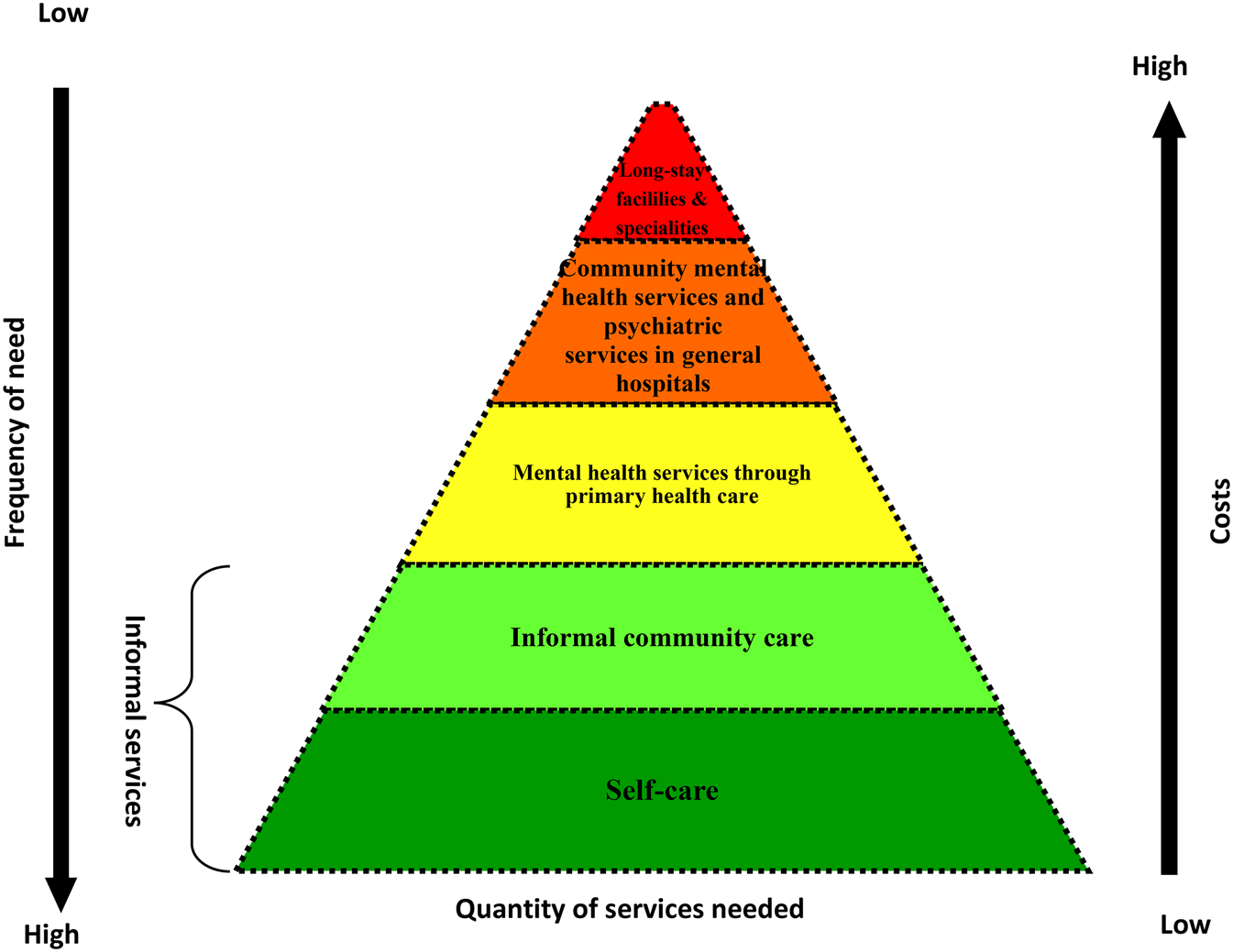

WHO has developed a pyramid framework for an optimal mix of services to provide guidance to countries on how to organize mental health services using the community-based approach (Fig. 1). The pyramid framework illustrates that most mental health care can be achieved at the community level through integrated health care services by training non-specialist health professionals (physicians, nurses and midwives) on the WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme and using community health workers and/or volunteers as a bridge between informal and formal health care services (WHO, 2017).

Fig. 1. WHO pyramid framework of optimal mix of services (source: WHO MIND project).

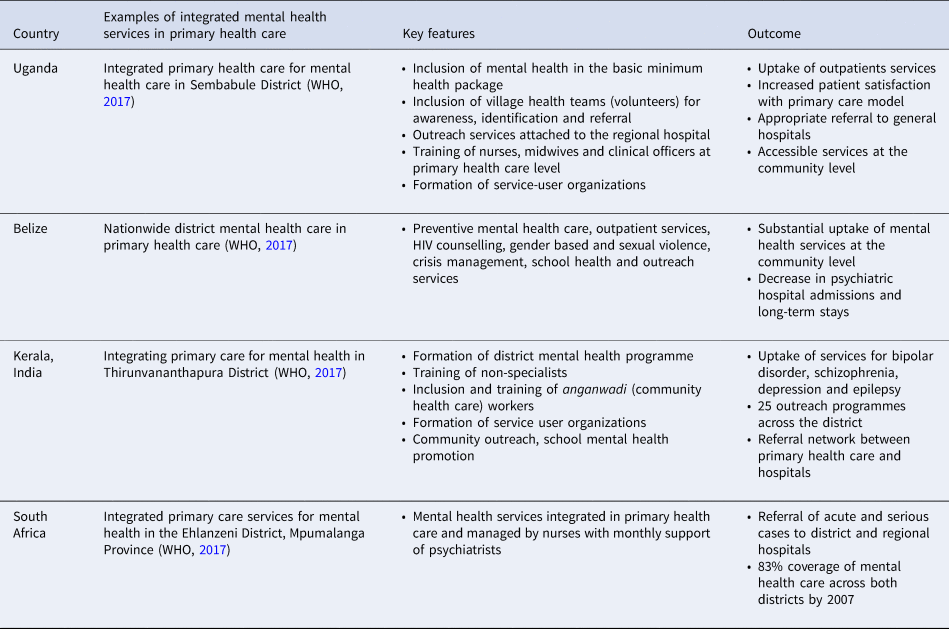

Using this approach, several countries have successfully integrated mental health services into primary health care services with encouraging results (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of integrated mental health services in primary health care in low- and middle-income settings

In addition to the countries in Table 1, Argentina, Belize, Chile, Islamic Republic of Iran and Saudi Arabia have successfully implemented integrated mental health services in primary health care either nationally or regionally with varying degree of success depending on government commitment, funding and capacity (WHO, 2008a, 2008b). The programmes were able to successfully manage priority conditions as reflected in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme.

Fostering peace through tackling mental health: the case of Somalia

Somalia's 30-year-old civil strife has severely disrupted social cohesion, broken down social norms and led to widespread psychological suffering. Long-standing conflict undermines trust between individuals, families, communities and their institutions (World Youth Report, 2003). With 70% of Somali's population under the age of 30 years, the vast majority of the population was born and grew up in the midst of conflict. This situation can lead children, young people and adults to normalize and potentially reproduce violence and conflict through retribution, joining armed groups and intimate partner violence (World Youth Report, 2003). Studies of adverse childhood experiences and trauma, such as hunger, violence and neglect, have shown an association with long-term chronic health conditions including mental health and substance use (Dube et al., Reference Dube, Felitti, Dong, Chapman, Giles and Anda2003). Therefore, neglecting to address the psychosocial impact of conflict will ultimately undermine peace, health and development.

The WHO country office in Somalia, in partnership with the IOM, UNICEF and the federal government, is currently implementing a pilot project on youth-oriented integrated MHPSS in the context of peace building. The project complements existing primary health care services and peace-building initiatives and tackles an important service delivery gap – MHPSS – that is currently not covered by any humanitarian or developmental programmes in Somalia. As part of this project, WHO and implementing partners are conducting a study on the links between mental health, conflict and peace building in order to provide evidence about the interplay between MHPSS and drivers of conflict in Somalia, and help to inform new evidence-based approaches and interventions that can be implemented as a follow-on to the project. It is being increasingly recognized among professionals working in MHPSS and peace building that interventions aiming to achieve build peace would benefit from closer links with mental health interventions, as both add vital elements to rebuilding social, economic and political structures.

Task shifting for integrated mental health services

The interventions in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme for priority mental, neurological and substance use conditions and the recommended psychological interventions, if implemented to scale, can fill the gap in treatment and mental health services in Somalia. These services can be delivered by integrating mental health services through, for example, the following task shifting approaches.

• Community outreach level: community and female health workers can be trained on: screening for common mental health illness; health education; psychosocial interventions that can be done at the community level; and referral pathways to primary health care units.

• Primary health care level: frontline primary health care workers (nurses, physicians, midwives, public health officers and social workers) can be trained to recognize and treat mental health illnesses that are treatable at the primary health care level in line with the intervention package in the Mental Health Gap Action Programme.

• General hospital level: referral networks established, mental health inpatient units integrated in selected general hospitals, and nurses, physicians and midwives trained on the Mental Health Gap Action Programme.

Investing in mental health is investment in development and peace building – two vital elements for post-conflict rebuilding of Somalia.

Financial support

None.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

Not applicable.