Introduction

Alexander Barton Woodside’s classic study, Vietnam and the Chinese Model: A Comparative Study of Vietnamese and Chinese Government in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century ([1971] Reference Woodside1988), remains one of the only works to deal with the first six decades of the Nguyễn dynasty as more than merely a prologue to French colonization (Cooke Reference Cooke and Reid1997, 269). It remains an essential resource for understanding this period of Vietnamese history despite criticism from those who think he overemphasized Southeast Asian indigenous structure (Kelley Reference Kelley2006, 346–50) and those who think he overemphasized Chinese influence (Cooke Reference Cooke and Reid1997, 277–78). Indeed, the main fault of the book is that its view that this supposed tension between “Chinese” and “indigenous” culture is the animating force of Vietnamese intellectual life. Woodside himself was aware that his project of “disentangl[ing] … the Chinese or Sino-Vietnamese characteristics of Vietnamese history” was “artificial,” and that Chinese learning was so completely absorbed “that its Chinese origins became irrelevant.” Nonetheless, the task he set himself of identifying a “Chinese model” transplanted to the Vietnamese environment led him to discover tension between Chinese and indigenous culture everywhere he looked (Woodside [1971] Reference Woodside1988, 1, 21).

The most piquant criticism of Vietnam and the Chinese Model comes from Woodside himself, who in his 1988 preface to the paperback edition describes the book as “schematic and somewhat court-centered,” suggesting several themes not sufficiently explored. Much of the revised preface deals with Lê Quý Đôn (1726–84), the outstanding authority of Vietnam and the Chinese model, of whom Woodside says, he was “perfectly aware that he belonged to a far-flung Confucian commonwealth which comprised, in time and space, something more than just the contemporary Chinese and Vietnamese governments. This commonwealth increasingly shared geographic, literary, and technical knowledge” (Woodside [1971] Reference Woodside1988, n.p.). Woodside's critique of his own work was emblematic of a general shift in English-language work on precolonial Vietnam.Footnote 1 The very categories that underlay Woodside's study, of East Asia and Southeast Asia, indigenous and foreign, have come under dispute (Taylor Reference Taylor1998). At the same time, the field of Vietnamese studies was turning to the invigorating streams of Cham and Khmer culture that opened up “new ways of being Vietnamese” in the South,Footnote 2 even as others looked increasingly at Sino-Vietnamese interactions and not just unilateral influence.Footnote 3 These new directions in the field allow researchers to move past the unhelpful binary of external influence versus indigenous structure, a binary that never adequately described Vietnamese society.

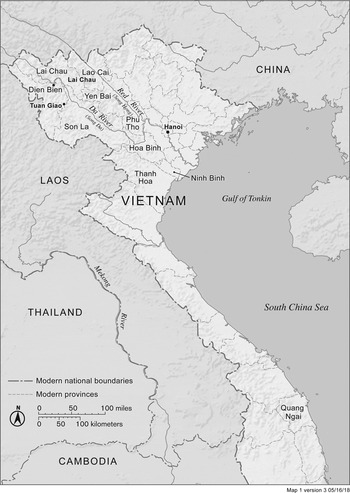

This essay explores a single text, Phạm Thận Duật's Hưng Hóa Địa Chí 興化地誌 (Hưng Hóa Gazetteer) to argue that the intellectual life of scholars in the early Nguyễn dynasty was not predominantly characterized by tension, resistance, or absorption. Rather, scholars like Phạm Thận Duật 范慎遹 (1825–85) actively produced knowledge within a dynamic and far-flung commonwealth (see figure 1). Instead of seeking to “disentangle” imported and indigenous influences, I begin with the assumption that the Confucian classics and academic trends that originated in the north were entirely naturalized in the Nguyễn dynasty, while affirming Woodside's observation that elites consciously participated in a “Confucian commonwealth.” While previous work tends to focus on how Vietnamese scholars assimilated Chinese influence, I show instead how Phạm Thận Duật used the gazetteer genre to generate new knowledge. His intellectual world was shaped by a northern canon, stimulated by the needs of the Nguyễn state, guided by Vietnamese authors, and determined by the particularities of the highland region he studied. Writing within the gazetteer genre, Phạm Thận Duật engaged with foundational classical Chinese texts, recent Vietnamese works, and the Qing-era kaozheng movement of evidentiary scholarship. And yet, as the account of the Chinese visitor Cai Tinglan shows, the intellectual world of Vietnam was not a “sinicized” frontier but a classicized center. Vietnamese scholars in the nineteenth century employed as they wished a shared canon of books and a literary language. This allowed for fruitful intellectual exchange with Chinese interlocutors, whether that exchange happened through books, through literary friendships like those between diplomatic envoys, or between actual scholars blown upon Vietnamese shores like Cai Tinglan 蔡廷蘭 (1801–59).

Figure 1. Sites mentioned in this article, with rivers and modern-day provincial borders included. Map by Ben Pease, peasepress.com.

Whether or not we refer to their broad community of learning as the “Confucian commonwealth,” few would dispute that Vietnamese scholars engaged in and contributed to a culture of knowledge that was international in scope. If Lê Quý Đôn and his counterparts saw themselves as members of this community of inquiry, how did they express that involvement? What did membership entail? What methodologies did members use to produce and contest knowledge? What aspects of this community were unique to Vietnam?

I chose Phạm's text to explore these questions for several reasons. It was written near the height of the Nguyễn dynasty's power, while it was still aggressively expanding into the hinterlands and before the beginnings of French colonization in the 1860s. As a gazetteer, its chapters engage with several different genres of writing, including geography, materia medica, and what might be called “ethnography” (Davis Reference Davis2015). And finally, Phạm's careful citation of books allows readers to trace his interlocutors and reconstruct his intellectual world. Phạm confidently rejected or reconfigured previous work, using textual citations to manifest his participation in a literary culture that transcended Vietnam. “New ways of being Vietnamese” were not limited to the south, but available to the Northern intellectuals like Phạm who actively engaged in and generated the intellectual trends of his time.

A Shipwrecked Scholar

How would a visitor to nineteenth-century Vietnam experience the Confucian commonwealth? An answer can be found in the account of Cai Tinglan, a Chinese scholar shipwrecked in Vietnam in 1835. Writing in classical Chinese formed the basis of his interactions with Vietnamese people, from high officials to humble teachers. As Cai records in his short book, Hainan Zazhu 海南雜著, on his way home to the Penghu islands from sitting the civil service examination, a storm damaged his boat and blew it off course. The sailors eventually chopped down the main mast in a desperate attempt to control the ship. After four or five days, the waves calmed and the ship drifted towards an unknown shore. Fishing boats approached, but the ship's passengers could not converse with them. The fishermen then wrote out two characters: 安南 (Annam). They had reached Quảng Ngãi Province, on the south central coast of Vietnam (Cai Reference Cai1959, 3).

Cai and his shipmates went ashore and registered with government officials. One evening, the Nguyễn officials that he met administered a civil service style examination test for him. It included questions on poetry composition and the Four Books and Five Classics (the Confucian texts that formed the basic curriculum of civil service examinations in both countries). He was given a deadline of mid-morning the following day to complete it. The following night, he was given another test. Soon after, the “king” (the Minh Mạng emperor, r. 1820–41), who had been informed of the arrival of the Chinese ship, wrote that since Cai was from a literary household, he should be given money to cover his travel expenses and an escort (Cai Reference Cai1959, 8). The Vietnamese apparently took steps to verify Cai's claim that he was a scholar. Cai gained official support, but only after a demonstration of his literary knowledge and skill.

A stream of visitors called on Cai to ask for samples of his writing and exchange poetry. He traded verses with none other than Phan Thanh Giản 藩清箭, a leading scholar who had already served as an envoy to the Qing court. In a more mundane exchange, Cai records that a teacher named Trần Hưng Đạo 陳興道 wrote a poem to summon Cai to drink with him. During their conversation, he informed Cai that Vietnamese schoolchildren studied the same books as their Chinese counterparts, albeit in handwritten manuscript copies, and that they had to use bricks and muddy water as paper and pen, without so much as a copybook to follow (Cai Reference Cai1959, 9). Within a few days, Cai was able to glimpse the literary standards of the palace and hear about the conditions of a humble school. Both engaged with the same texts that shaped Cai's own education. For Cai, as a Chinese observer who had not previously had occasion to reflect on the intellectual world of Vietnam, this was a revelation. For his Vietnamese interlocutors, it was simply the fabric of their lives.

This is not to suggest that Vietnamese literary culture or education was identical to that of China. As Alexander Woodside suggested in his revised preface, it was independent and Vietnam-focused. The Nguyễn officials did not simply take Cai's word about his identity; they demonstrated their authority by examining him. Furthermore, since he does not comment on it, it seems unlikely that Cai understood the significance of his interlocutor's name, Trần Hưng Đạo, the same name as the revered thirteenth-century resister to Yuan dynasty military campaigns in Vietnam. Was the local teacher really named after this hero? Or was he teasing or testing Cai when he told him this name? In any case, it indicates the existence of a world of historical and textual allusions that were outside of a Chinese canon and largely unknown to Cai and his compatriots.

Cai Tinglan's literary training allowed him to communicate and get help during his accidental vacation in the Nguyễn realm. He was relieved to find people who shared a common education based in the Four Books and Five Classics. The term “Confucian commonwealth” describes well Cai Tinglan's experience of passing being transported to a land of examination questions and shared educational norms. And yet, this literary world was not identical to that of China, nor was it a lesser version. By examining the work of a contemporary Vietnamese official, we can see precisely how he tested the canon through the process of khảo chứng/kaozheng and innovated within the framework of the gazetteer.

Phạm Thận Duật and His Gazetteer

Phạm Thận Duật was born in Ninh Bình Province in the Red River Delta, an educational center of Nguyễn Vietnam. Soon after passing the civil service examination at the provincial level in 1850, he was posted to the northwestern border region. Phạm was posted to the enormous frontier region along the borders of China and Laos, to the west of the Red River, officially known as Hưng Hoá since 1469.Footnote 4 Its former territory is today divided into the provinces of Sơn La, Lai Châu, and Lào Cai, as well as parts of Phú Thọ, Yên Bái, and Hoà Bình (Nguyễn Đức Thọ, Nguyễn, and Papin Reference Nguyễn, Văn Nguyên and Papin2003, 1506). This region was “an imperial frontier zone,” so remote and mountainous that garrisons and fortifications were not built there, where “imperial power enjoyed only nominal authority over the mountainous boundaries of its domains” (Le Failler Reference Le Failler2011, 42–43). Phạm's work in the highlands came at the tail end of the early Nguyễn dynasty's push to more firmly incorporate the northern highlands into central state control. Phạm Thận Duật wrote the Hưng Hoá Gazetteer in 1856, when he was the new department magistrate of Tuần Giáo (in today's Điện Biên Province). He spent the next twenty years on assignment in the northern part of the country (Nguyễn Văn Huyền Reference Nguyễn, Lâm and Nhân2005, 66).Footnote 5

The Hưng Hoá Gazetteer is written in literary Sinitic, with a few glosses in the Vietnamese vernacular script, Nôm, to record local terms for various plants and places. It was written in a mode that we know Phạm was familiar with from his list of citations (see table 1)—that of the gazetteer (fangzhi 方志). His title and chapter subjects evidence that he was working within this genre. Administrators had long written and compiled gazetteers to describe the localities under their jurisdiction in China as in Vietnam. The gazetteer genre, although often quite derivative, allowed authors to fit fresh insights and information into a widely accepted format. In other words, authors could build on existing structures of knowledge, or in the case of an entirely new gazetteer, like Phạm's, they could create a foundation, designed in a familiar way, for future scholars to use or expand as they saw fit.

Table 1. List of citations.

Compilers of gazetteers trace the genre back to the Zhou dynasty's (ca. 1045–256 BCE) requirement that localities submit maps and other information to the central government. The first writing in the gazetteer genre may be the Yugong 禹貢 section of the Shangshu 尚書, which describes mountains, rivers, local products, and other geographic features of the “nine provinces” of early China. The gazetteer genre took the form we know only in the Song dynasty (960–1279), and production of gazetteers exploded by the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) (Dennis Reference Dennis2015, 1–2, 22–24). In Vietnam, a descriptive geography was written in the reign of Lý Anh Tông (r. 1138–75), but is no longer extant. The first extant geography is Dư Địa Chí 與地誌 (Geographical Treatise) of 1435, written by the Lê intellectual Nguyễn Trãi. Through the Lê dynasty, Mạc dynasty, Lê Restoration, and Nguyễn dynasty, several geographies were produced, some commissioned by the government, and others the work of individual authors.

Phạm Thận Duật's handwritten manuscript was on a smaller (and more detailed) scale than the better-known imperially commissioned geography from the same period, Đại Nam Nhât Thống Chí 大南一統志 (The Encyclopedia of the Empire of Đại Nam), commissioned in 1849. It is also markedly different from a comprehensive Vietnamese gazetteer, Đồng Khánh Địa Đu Chí 同慶地與志, completed just a few decades later (Nguyễn Đức Thọ et al. Reference Nguyễn, Văn Nguyên and Papin2003). That gazetteer, which was compiled by a number of officials who filled out standardized forms for the counties under their control and then submitted them to the throne, does not cite other books and does not contain the detailed observations that characterize Phạm's work (see also Davis Reference Davis2015, 335).

Phạm used the format of gazetteers to organize his chapters, generally choosing topics shared by most gazetteers:

Table of contentsFootnote 6

1. 疆域 Cương vực (territory)

2. 丁田稅利 Đinh điền ngạch thuế (population and taxes)

3. 山川 Núi sông (mountains and rivers)

4. 祠寺 Chùa chiền (temples)

5. 城池 Thành trì (city wall and moat)

6. 古蹟 Cổ tích (ancient sites)

7. 氣候 Khí hậu (climate)

8. 土產 Thổ sản (local products)

9. 習尚 Phong tục (customs)

10. 土字 Thổ tự (local script)

11. 土語 Thổ ngữ (local language)

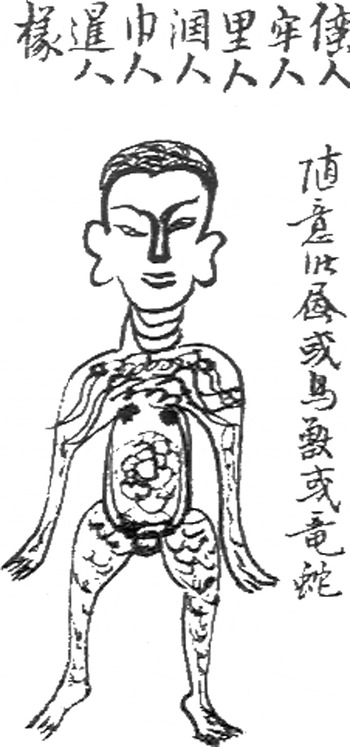

The text includes maps, drawings of irrigation systems, drawings of local ethnic groups (see figure 2), and an extensive Tai lexicon. Unlike most gazetteers, it lacks chapters on biographies of local worthies, perhaps because he could find no one to fit into the conventional mold of scholar-officials and chaste widows. He does include several tales of exemplary women in his chapter on historic sites: mainly heroic or martyred women whose spirits infuse a location with spiritual power.Footnote 7

Figure 2. Drawing of a tattooed local man (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 54b).

Phạm Tuận Duật explained his motivation, methods, and audience in his preface to the book. He wrote that an official gazetteer of Vietnam, Hoàng Việt Địa Dư Chí 皇越地與誌 (1833) focused exclusively on districts nearer to the heartland.

The land and products of the upstream districts are all neglected. When I arrived here, I wanted to consult maps and records, but there was nothing to analyze or verify (khảo chứng 考証).Footnote 8 I carefully read recent documents and relied on what I picked up myself to complete this book. Although it is still insufficient and incomplete, at least it has the value of filling in some gaps. One can also rely on the maps and illustrations when they serve as officials here. (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 1b)

Phạm's invocation of khảo chứng (Chinese: kaozheng) gives us insight into his methodology. Often translated to English as “evidential research,” the kaozheng movement in Qing China was typified by a “critical attitude toward evidence, the broad gathering of sources, and the discriminating employment of investigative methods” (Ng and Wang Reference Ng and Wang2005, 244; see also Davis Reference Davis2015, 334–35). Phạm clearly states that he used textual research and first-hand observation in order to put together a guide for future administrators.

Why would administrators need this kind of guide? In his study of local gazetteers in late imperial China, Joseph Dennis (Reference Dennis2015, 3–4, 51–54) argues that gazetteers were important vehicles for binding “locales to the centralizing state and dominant culture,” serving as “foundational blocks in building the imagined empire.” Phạm and his gazetteer certainly played a role in the Nguyễn government's goal of extending central control into marginal areas (Davis Reference Davis2015). But there was symbolic meaning to creating a local gazetteer in addition to practical value. Increasing the volume of writings about a locale (“there was nothing”) would affirm the designation of it and the Nguyễn realm more generally as a “domain of manifest civility” (Kelley Reference Kelley2003, 72).

The knowledge Phạm produced was meant to guide and aid other Nguyễn administrators, but the book went dormant. As the Vietnamese state was subsumed by the French empire, the career path once expected by successful scholars like Phạm was no longer as viable. The manuscript was collected, but not obviously used, by the French colonial regime, in the library of l'Ecole Francaise d'Extreme Orient. It existed as a handwritten manuscript and was not printed.Footnote 9

The Revival of an “Ethnographer”

There has been a surge of interest in Phạm Thận Duật in Vietnam over the past two decades, including a volume on his “life and works” published in 1989 (Nguyễn Văn Huyền Reference Nguyễn1989), which preceded a government-sponsored reprinting and translation of his complete works (Phạm Đinh Nhân Reference Phạm Đinh2000), as well as a volume of scholarly essays and reprints of newspaper articles commemorating his life (Đinh and Phạm Reference Đinh and Nhân2005). Phạm Thận Duật is presented in these works a patriot and an innovative scholar, specifically, as an ethnographer. In the estimation of some historians, his first-hand empirical investigation of local communities and sensitivity to differences in culture anticipate academic approaches of the following century (Lê Reference Lê Trí, Lâm and Nhân2005, 105; Nguyễn Quang Ân Reference Nguyễn, Lâm and Nhân2005, 290; Phan Reference Phan, Lâm and Nhân2005, 439). In English-language scholarship, Bradley Camp Davis too sees Phạm as a scholar whose methods prefigure the field of ethnography, but emphasizes that his pursuits were in the service of imperial expansion. Davis refers to the book as “imperial Vietnamese ethnography,” connected to similar colonial projects in Qing China. He argues that Phạm's “central goal” was “producing an ethnographic picture of uplands space” (Davis Reference Davis2015, 324–25, 338).

Part of the appeal of revisiting Phạm's work is that he seems to share our contemporary interests in ethnography, environment, and language. Indeed, the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer is among the first Vietnamese texts in Han script to mention the Hmong or Miao, and the first time a Vietnamese author differentiated between the White Hmong and other groups (Nguyễn Văn Huyền Reference Nguyễn, Lâm and Nhân2005, 18). His book is an extraordinary resource for understanding the northern highlands before French colonization, and scholars have mined it for information on indigenous people and local languages. And yet, his chapters on customs and language are just part of the book as a whole, which is after all a gazetteer, not an ethnography. A too narrow focus on the local customs and language chapters of the book risks overlooking Phạm's other chapters, particularly on historic sites and materia medica.

The chapters on local customs (phong tục 習尚) and local language (thổ tự 土字) and (thổ ngữ 土語) in the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer contain valuable information on a range of topics. Phạm differentiates between thirty different local groups. He covers such topics as farming, fortune-telling, religion, demons and exorcism, medicine, marriage, funerals, and handicrafts. Phạm Thận Duật made a concerted effort to learn about the local Tai dialect and wrote up a lexicon of terms in the Tai script glossed in Han characters.

The Nguyễn dynasty was established in 1802, after the turmoil of regional divisions in the waning decades of the Lê dynasty and the turbulent Tây Sơn era (1778–1802). By the early nineteenth century, the Nguyễn dynasty was aggressively incorporating the northern highlands, particularly during the reign of the second emperor, Minh Mạng (r. 1820–41). Although upland spaces have largely been neglected in national histories and deemed marginal in all ways, they were in fact economically vital to the state. Vũ Đường Luân (2014, 357–58) has shown that tax revenues from the Sino-Viet uplands in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries were many times that of the Red River Delta and the central coast, thanks to mining revenue and customs transactions on the sale of metals (see also Li Tana Reference Li2012). Lucrative overland trading between northern regions of the Nguyễn empire and south China accounted for a much bigger proportion of Nguyễn tax revenue in its early decades than even maritime trade, eclipsing tributary trade in volume (Li Tana Reference Li2012, 72–75).

The ability to understand, differentiate, and count the local population was of obvious use to the state and its representatives. Keeping an updated record of the taxable population was a key task of administrators. To that end, Phạm’s chapter on taxes quantifies the population while making distinctions between different groups. He includes population numbers of taxable subjects and acreage of taxable land. He distinguishes between Qing people (Thanh nhân 清人), Ming people (Minh hương 明鄉), Nùng 儂人, and Mán 蠻人, all of whom paid different tax rates, collected in taels of silver. Phạm and other Vietnamese writers used the term “Qing people” to designate more recent Chinese arrivals who came in order to take advantage of economic opportunities; they worked as miners, or set up inns, restaurants, and shops in river towns that sprang up along trade routes and near mines. The local perception was that they would not stay long (Vũ Đường Luân Reference Vũ2014, 362–65), and they are therefore distinguished from Minh Hương who arrived during the fall of the Ming dynasty in the mid-seventeenth century and had deeper local roots and engaged in different forms of labor. While Minh Hương, Nùng, and Mán people were taxed at the rate of one silver tael per person, Qing people were to pay two or three taels for person, depending on their district of residence (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 9a–14b). Since land and products were also taxed (in strings of copper coins and in kind), it is likely that Qing people were taxed at the higher rate because they engaged in commerce, rather than in agriculture or craft production. Elsewhere, Phạm tells us that the Thổ, Mán, Mèo, and Nùng generally used a barter system rather than cash (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 49b). We also learn from this chapter that Hưng Hóa, though large in territory, was sparsely populated.Footnote 10

Was Phạm more sensitive to local customs and traditions of the highlands than other men of his background and time? By looking at earlier Vietnamese texts on the topic, like Hưng Hóa Xử Phong Thổ Lục 興化處風土錄 (1778) by Hoàng Bình Chánh, we can wager a qualified yes. Though Davis singles out Phạm's efforts to record local place names rather than just centrally imposed Vietnamese names, it was common practice; it was done in the earlier Hưng Hóa Xử Phong Thổ Lục. Nor was Phạm the first Nguyễn official to promote learning highland languages (Poisson Reference Poisson and Gainsborough2008, 20), though perhaps he was the first to make such a comprehensive guide.Footnote 11 Phạm's work stands out, however, in the quantity and seriousness of his observations. By way of comparison, in his introduction Hoàng Bình Chánh writes of the local inhabitants that “the men are treacherous and the women are lascivious”—using familiar terms of dismissal and non-engagement. He goes on to write in a derogatory tone that women and men commit adultery, that men marry out of their clans, that the people do not pay attention to their respective ages (and thus to hierarchy), and that they “refuse to obey” (Hoàng Reference Hoàng1778, 4). By contrast, Phạm offers a serious and relatively even-handed accounting of local customs and traditions. Phạm at times gently corrects the record, as when he notes of an earlier gazetteer on the region: “Mr. Trấn's Records of Hưng Hóa says, ‘People in the district care little for gender and rank,’ but that is no longer entirely true” (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 50a). His methodology was to collect and record local customs, while comparing what he learned to the textual record.

Despite this even-handedness, Phạm's drawing of the inhabitants of Hưng Hóa allows us to see how he positioned himself in relation to his constituents and in relation to well-worn Chinese tropes of the “southern barbarian.” When Chinese writers conjured up the tattooed southern barbarian, Vietnamese were often carelessly folded into that category.Footnote 12 Lowland Vietnamese, reading Chinese books and producing their own, also acknowledged the existence of a tattooed barbarian, but they did not associate that image with themselves.Footnote 13 Phạm included a drawing of a local inhabitant, labeled with six different names for ethnic groups (see figure 2); groups that he mentions all practice tattooing in his customs chapter (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 47a). The label says they have tattoos of birds and beasts or dragons and snakes. Two other images show local inhabitants clad only in loincloths. This is a far cry from the cap and robe-wearing Vietnamese official.

Moreover, Phạm's self-description is of someone engaging in a “civilizing mission” with the goal of moving the local residents from a state of primitive ignorance into the present-day of virtuous, Confucian-inflected customs. He invokes the ancient sage kings who taught the people how to write instead of using knotted cords, how to enter into formal marriages instead of living chaotically, and how to bury their dead rather than tossing them in the river. “Before the time of the Hùng Lạc kings,” Phạm muses, “maybe the people of our country were once the way the locals here are now.” But in the intervening hundreds and thousands of years, Phạm continues, the country has become “civilized” such that people like the Qing governor-general of Yunnan, Lao Chongguang 劳崇光 (1802–67), describe it as a “domain of manifest civility” (văn hiến chi bang 文獻之邦) (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 52b).Footnote 14 His reference to Lao Chongguang, who served as the Qing inspector general and later governor-general to Guangdong and Guangxi along the Vietnamese border from 1852, is a rare glimpse into transregional literary networks. Lao wrote a preface for a Vietnamese book (see table 1), and presumably corresponded with Vietnamese scholars.

It is worthwhile here to pause and examine the word Phạm used for “civilize”: literally, “draw near to the Central Country” (進於中國). The Central Country, or as it is often translated, “Middle Kingdom,” is now the most common word for “China.” But its meaning here is more complicated. As Phạm stated, Vietnam is considered a domain of manifest civility, and has been civilized since the time of the Hùng dynasty (c. 2879 BCE–c. 258 BCE), a southern dynasty based in the Red River delta.Footnote 15 Phạm here views Nguyễn Vietnam as the Central Country. This becomes clear later in the passage, where Phạm writes:

Although I hold merely a minor post here, I am responsible for making manifest the virtue of the court in order to improve the hearts and customs of the people. How could I neglect civilizing [中國進] these few Mán Liao? As Mencius said, to lose one's place in the ranks many times, or in other words to look after someone else's flock and fail to find pasture, this can be said of my situation. (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 52b)

Phạm cites Mencius to downplay his ability to succeed, but, modesty aside, his self-defined task is clear: to change the customs of the locals to accord with that of the “Central Country” and its court, here indicating Nguyễn Vietnam. What on the surface appears to be the most derivative vocabulary imaginable is in fact infused with a sense of Vietnamese place and history. This is reinforced by his reference to the Hùng Lạc kings, a Red River–based dynasty unique to Vietnamese legend. These references most likely would have gone over the head of Chinese readers like Cai Tinglan, but they make perfect sense in the Vietnamese context. In order to fully understand Phạm as a scholar and contextualize his work, we must look back to the books and culture of knowledge that influenced his views. Luckily, he has provided us with a bibliography.

A Nineteenth-Century Bibliophile

The words Phạm Thận Duật used to describe his understanding of the world and his place in it are rooted in his education and the books he read. The Hưng Hóa Gazetteer, like all texts, is indelibly shaped by what the author read (Darnton Reference Darnton1990, 111). It is special in that the author's invocations of these texts invite us to ponder just how it was shaped by other texts. Phạm's frequent citations of texts give a good sense of the books available to and respected by nineteenth-century Vietnamese literati and the culture of knowledge that shaped him and his counterparts. In the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer, he cites dozens of books by name,Footnote 16 ranging from ancient Chinese histories to recent Vietnamese encyclopedias, from poetry to medical treatises (see table 1).

Phạm assembled his data both from first-hand observation and from his reading of a wide range of Vietnamese and Chinese printed texts, and he carefully cites this variety of sources. The Hưng Hóa Gazetteer—through its constant evocation of printed books, manuscripts, and inscriptions—traces the transmission, consumption, application, and production of knowledge. A close reading of the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer thus reveals not only the uses of Vietnamese texts, but also the unanticipated careers of books once they left the borders of the Chinese empire and entered into conversation with Vietnamese books. Phạm participated in a culture of knowledge that was both transregional and translocal, but also rooted in its Vietnamese context. Like his Chinese counterparts, Phạm was well-versed in the Four Books and Five Classics and quoted them extensively. He was aware of and engaged in some of the same debates and methods that animated Chinese scholars: the role of qi versus li; observation and experiment versus textual study; and medical theories and practice. Needless to say, not all books that circulated in China reached Vietnam, nor did most Chinese scholars read Vietnamese texts. Phạm, for example, extensively cites the Vietnamese literatus Lê Quý Đôn, whose influential writings would have been largely unknown north of the border.Footnote 17

The titles he cites are consistent with Cynthia Brokaw's division of “bestsellers of late imperial China” into three categories: educational texts, practical guides including medical texts, and literature (Brokaw Reference Brokaw, McDermott and Burke2015, 219–29).Footnote 18 In terms of educational texts, it is no surprise that Phạm would read and cite the Classics, which were baked into the literary culture of the time and kept relevant by the classics-based civil service examinations held by the Nguyễn state. He also cites official histories from both China and Vietnam. The trend of greater accessibility of medical information through the publication of medical primers and rhyme books from the late Ming is visible in his work. The Fundamentals of Medicine (Yixue Rumen 醫學入門) in particular was reprinted several times, so it is no surprise that it was available in Vietnam (Leung Reference Leung2003, 134–35). In addition to the Ming novel Journey to the West (Xiyou Ji 西遊記), Phạm quoted several poems, including one by the Tang poet Du Fu 杜甫 (712–770) (not included in table 1). In addition to the titles collected in table 1, Phạm cited genealogical tables (gia phả/jiapu 家譜), hearsay, legend, and temple inscriptions and records, demonstrating how his conversations and observations entered the written record. The source he cites most frequently is “documents from the Hàn Lâm academy” (Hàn Lâm Viện 翰林院), suggesting that he was able to access reference materials while in the capital, Huế.

Phạm's book shows the robustness of Vietnamese printing and book culture—he cites nearly as many Vietnamese texts published or circulating in manuscript as Chinese printed sources, and he uses them more extensively. The Vietnamese books he cites were mainly from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, while many of the Chinese texts he cites were classics written well before 1500. The earliest Vietnamese text he cites is Nguyễn Trãi's Lam Sơn Thực Lục (1431). It seems as though Vietnamese texts served as up-to-date reference books, while many of the Chinese books were foundational education texts. It is also possible that more up-to-date Chinese books were more difficult or expensive to obtain, as indicated by the schoolteacher Trần Hưng Đạo's lament. On the other hand, Phạm may have seen Chinese books as less relevant to his topic, the history and culture of Hưng Hóa, and thus did not cite them in this particular text. Either way, Phạm Thận Duật's methods show that he was not a passive recipient of textual knowledge, nor was he a merely replicating the classics. He critically examined existing sources to test them against what he learned in the field.

Methods: Analyzing and Verifying the Evidence

Phạm Thận Duật's experiences as a colonial administrator of Vietnam's far northwest were thus mediated through a long tradition of systems of knowledge shared and adapted between China and Vietnam, particularly with regard to natural history and geography. Even as he was conducting first-hand research into the climate, flora and fauna, and language and customs of Hưng Hóa, he was contributing to, testing, and verifying received texts. Phạm Thận Duật referred to his process of critically investigating textual sources and cross-referencing them with empirical observation as khảo chứng (kaozheng 考証) (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 1b), literally “analyze and verify,” connecting himself to the “kaozheng” scholarly approach also prevalent in Qing-era China (Davis Reference Davis2015, 334–35).

A prime example of this approach is his discussion of a poem in the chapter on “ancient sites.” Phạm records several poems attributed to Lê Thái Tổ, the posthumous title of Lê Lợi, the founding emperor of the Lê dynasty (1428–1527). Lê Thái Tổ expelled Ming troops from Vietnam after twenty years of Chinese occupation. In 1431, Lê Thái Tổ subdued the pro-Ming Tai chief Đèo Cát Hãn in Hưng Hóa (now Lai Châu Province). Phạm discovered textual records of two poems attributed to Lê Thái Tổ written to commemorate the victory. The first was inscribed on a boulder on a hilltop over the Bờ river in Lai Châu in 1431.Footnote 19 A second dates to 1432 and was located in Vạn Bờ in the village of Hào Tráng in Đà Bắc County (in present-day Hòa Bình Province). Since both were said to be in what was then Hưng Hóa, it was essential to include these imperial traces in the ancient sites chapter. However, Phạm had doubts about the number, location, intention, and author of these inscriptions. To verify, he compared five texts, assessed oral legends, and possibly visited the second stele himself. He also did a stylistic comparison of the poems to one he was certain was written by Lê Thái Tổ.

The first poem, he writes, quoting its preface, was inscribed on a boulder to “warn future generations of Mán leaders against defiance.” It was placed there in 1431 after the quelling of Đèo Cát Hãn's anti-Lê rebellion. In his preface to the poem, Lê Thái Tổ placed his struggle against the “Mán” people (highlanders differentiated from the lowland Kinh) in a long time-scale of dynastic wars with marginal groups, suggesting that resistance to state power was futile:

In the poem, Lê Thái Tổ not only figuratively registers the land in the maps and records of the empire, he literally inscribes the landscape with his threatening words.

Phạm found the second poem in “the records in the Hàn Lâm academy,”Footnote 21 dated 1432. It reads:

The preface of this poem states: “After defeating Cát Hãn [I arrived here], I made this poem to warn future generations of barbarians. They have the faces of men but the hearts of beasts. If they turn their backs on us they will be destroyed. And the strategy for advancing troops down the rivers Thao and Đà is excellent and smooth sailing.”

Phạm puzzled over the difference in the intention of the two poems: “In the records of the Hàn Lâm Academy, comparing the two prefaces, the first one says it is in order to warn future generations of Mán chiefs to be obedient. Others say it is so that future generations of the royals know the strategy [for subduing the borderlands].”

To verify that the first poem was indeed written by Lê Thái Tổ, Phạm compared the style to a third poem attributed to him, recorded in Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư (the official historical annals) under the year 1430. Like the first poem, it was inscribed in a border region, Cao Bằng, in order to reassure loyal subjects and intimidate rebels.

Comparing this to the first poem, Phạm opines that “[t]he poem that says ‘Wild rebels dare to flee punishment/While border people have long awaited our revival’ etc. shows the unity of the poetry, so it is not without reason that it is considered the poem of Lê Thái Tổ” (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 23b–24a). Since the intentions and sentiment of the two poems are the same, it suggests that the first poem is genuine. Yet Phạm still has doubts, since he cannot verify that Lê Thái Tổ ever personally visited the region. The Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư records that he sent his son Tư Tề in his stead. “Could it be that originally [Lê] Thái Tổ went there, and the history left it out?”

As for the second poem, Phạm thinks the line “on account of my age” seems appropriate, as Lê Thái Tổ would have been the advanced age of forty-eight when it was composed, but he is suspicious of the honorary title used to identify Lê Thái Tổ. Even more problematic is the location. According to Phạm, the Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư, the Hoàng Việt Thi Tuyển, the records of the Hàn Lâm Academy, and Hưng Hóa (Thực) Lục use different place names and honorific titles when discussing the poem, muddying the waters. “How could they make such a significant mistake?”

Moreover, Phạm follows Mr. Trấn in judging that the lines of the preface recorded in the Hưng Hóa (Thực) Lục that described the locals as having “a man's face but the heart of a beast” are “not entirely believable.” Indeed, a subscript notes that upon further examination, the characters “a man's face but the heart of a beast” were not present on the original stele. Phạm does not entirely trust Mr. Trãn's research, which he describes as vague and irresponsible for omitting all mention of Đèo Cát Hãn, the original reason for the poem.

Phạm had heard passed-down stories that claimed that the stele was so spiritually potent that those who gazed at it would die. Phạm rejected this explanation, opining that local residents used “ghosts to scare people away” so that no one would read the stele and form negative views of them and their rebellious past. “Old rumors are passed on anew, and after a while they start to seem true” (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 26b). He concludes by stating that “it is the responsibility of leaders to instruct the people” so that they do not pass on foolish stories.

Is Phạm Thận Duật engaging with kaozheng evidentiary methods, or is he simply rigorously and conscientiously verifying information? In addition to his own invocation of the term kaozheng, we can affirm that Phạm Thận Duật was up to date with methodologies popular in Qing China. At the very least, Phạm read and cited Lê Quý Đôn's 1773 encyclopedia, Vân Đài Loại Ngữ. Lê Quý Đôn engaged deeply with academic trends in China, and was able to obtain books and meet with scholars during his embassy to China in 1760. Throughout the Vân Đài Loại Ngữ, Lê Quý Đôn compares and analyzes different texts in much the same way as Phạm does. Phạm's analysis of poetry is noteworthy in that it engaged with kaozheng methodology in order to verify Vietnamese texts. It shows that the intellectual tradition in the north of Vietnam was not held back by Chinese influence, but propelled forward. Further examples of these methods are found in the local products chapter.

Materia Medica in the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer

We can see the influence of textual knowledge most strikingly in the chapter on local products. Hưng Hóa was an ideal laboratory for botanical research. Its insalubrious climate and misty mountains generated both diseases and the flora and fauna that could be deployed as medicines against them. Like most gazetteers, the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer includes a chapter on local products (thổ sản 土產). In this case, Phạm focuses on flora and fauna that could be sold as commodities. Some could be used as food or for building material, but most were medicine. This chapter evinces strong influence from the bencao genre (materia medica or natural history), or more specifically, Li Shizhen's magisterial 1596 Bencao Gangmu. Phạm situated what he learned locally within a system of knowledge exemplified by the Bencao Gangmu and typical of the bencao genre.

In contrast to Li Shizhen, whose goal was comprehensiveness, Phạm was keen to inventory useful local resources in just one part of the Nguyễn empire. Phạm's botanical explorations remind us of the riches that could be made in the highlands. He describes Himalayan ginseng (tam thất 三七), tobacco (yên thảo 煙草), golden-haired dog's spine fern (kim mao cẩu tích thảo 金毛狗脊草),Footnote 24 dappled bamboo (ban trúc 斑竹), canarium nut (“tram trắng” 橄欖),Footnote 25 wild yam (“củ nâu ” 禹餘粮), pears (lê 梨), monkey blood (huyết hầu 猴血), Dendrobium nobile (hoàng thảo 黃草),Footnote 26 black cardamom (sa nhân 砂仁), five-clawed chicken (ngũ trảo kê 五爪鶏), ant eggs (“trứng kiến” 蟻蚳), Anhvu carp (gia ngư 嘉魚), purple ants’ nest (tử nghị sào 紫蟻巢),Footnote 27 various kinds of bees (along with wax and honey) (phong 蜂), heartwood insects (“sâu củ đao” 朷蟲), green hornbills (hắc thổ phượng hoàng 黑土鳳凰), horses (mã 馬), lacquer trees (tất mộc 漆木), cotton trees (bồng mộc 蓬木), yellow kudzu (hoàng cát 黃葛), eaglewood (cốc 穀), poison arrow trees (Antiaris toxicaria) (tiễn độc thụ 箭毒樹), and various ores including those of gold (kim khoáng 金礦), copper (đồng khoáng 銅礦), and saltpeter (tiêu 硝).Footnote 28

The local products chapter blends empirical observation with citations from books. Like the Bencao Gangmu, Phạm's text is studded with citations and references to guide the reader along the author's intellectual path. Both the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer and Bencao Gangmu are textual curiosity cabinets. Li Shizhen cited hundreds of books by name. In his much slimmer volume, Phạm Thận Duật cites sources as disparate and distant in time as a Tang dynasty gazetteer to Lê Qúy Đôn's encyclopedic Vân Đài Loại Ngữ within a few lines. This style of writing makes the Hưng Hóa Gazetteer less like the more concise Đồng Khánh Địa Đu Chí and more like Vân Đài Loại Ngữ, which likewise cites a dizzying array of books one after the other.Footnote 29 I have attempted to catalogue in table 1 mainly the books that Phạm cited directly, rather than quotes within quotes, though the boundaries are not always clear. The practice of citing earlier texts was common in premodern literary Sinitic texts. Authors saw themselves joining an ongoing dialogue. Phạm's text shows us which texts he was engaging with and what issues he deemed important.

The very first entry, on Himalayan ginseng, typifies Phạm's reliance on the Bencao Gangmu. It is drawn almost entirely from the book, citing it directly by author and title. Nine individual entries for local products explicitly cite the Bencao Gangmu, or even instruct the reader to “see Bencao Gangmu,” suggesting that his readers would have had access to the full text. Sometimes Phạm quotes the Bencao Gangmu directly, but he often condenses or paraphrases, and he always adds his own additional thoughts or observations. In fact, his reliance on the Bencao Gangmu is so pronounced that he even notes when it does not have an entry for a local product, as in the case of hoàng thảo 黃草.

Local medicines are described as particularly useful for healing local diseases. This is true too of non-native plants, like tobacco, which was present in Vietnam by the early seventeenth century.Footnote 30 Tobacco was grown throughout Hưng Hóa and was nicknamed “herb of longing” (tương tư thảo 相思草) (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 32b).Footnote 31 Phạm deemed it an efficacious preventative medicine:

It is hot and toxic. It can ward off mountain mists and miasmic fog, so the local people ingest it a lot. The people of the heartland also ingest it a lot, instead of alcohol. Once the smoke enters the mouth, it spreads throughout the body, burning like fire and smoke. It causes one's energy and lifeblood to waste away. People with a deficit of yin should therefore avoid it. (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 32b)

In some cases, the local climatic conditions were said to produce both disease and efficacious medicines. For example, Phạm writes that places that produce black cardamom, a useful remedy for cold and heat induced diseases and sores, are the very places that have a lot of miasmic air (chướng khí 瘴氣).

In other cases, Phạm seems to be looking for products that were long associated with the Sino-Vietnamese highlands in books, even when there is not much in the way of local attestation of their use. In these cases, Phạm evaluated and sometimes dismissed inherited knowledge. Monkey blood is one such example. In China's southern imaginary, nonhuman primates were a key component of an exotic southwest. The plaintive, human-like cries of gibbons echo through Tang poetry, and Ming literature speaks of monkey blood as a valuable dye, medicine, or potion that makes spirits visible, as well as of the ambivalence of obtaining it by killing sentient beings.Footnote 32

Monkeys appear in materia medica as well. As Phạm notes, “in the Bencao Gangmu, different kinds of macaques’ heads, bones, hands, and skin are all described in detail. But it does not talk about monkey blood” (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 34b). Phạm writes about monkey blood as a medicine, even though he does not seem to have encountered any first-hand knowledge of its use. While Chinese writers ascribed the use of monkey blood to non-Han people of the south, it seems that on the other side of the border, the Vietnamese knew it as a remedy sought by the Chinese:

The monkeys birth their young in the mountains and their blood settles in caves. Qing people take cotton and silk or sticky paper and gather it up to form it into flat slices. According to their folklore, it can reduce phlegm, stop asthma, and disperse blood. Nowadays people make it into medicine for those with these illnesses.… A local saying has it that that this is not monkey blood, but just a kind of rosin from the mountains that is mistaken for monkey blood. (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 34a)

In this passage, we see Phạm wrestling with the differences between written sources and local informants. Just as in the case of the poems purportedly written by Lê Thái Tổ, Phạm makes visible his process of critically examining the existing evidence. Other representative examples of his approach come in his descriptions of the Anhvu carp (gia ngư 嘉魚) and the eaglewood tree, both of which he matches to different terms in the ancient Classic of Poetry (Shi Jing 詩經) (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 36b, 42b). As in the case of monkey blood, since a classic text, in this case the Classic of Poetry, mentions that “the South has gia ngư,” Phạm is interested in rectifying it with local fish species and providing an overview of the various names of this single type of fish.

Although Phạm privileged written texts, it seems that he made an effort to interview locals and collect information any way that he could. He cites conversations with local chiefs, hearsay, and legend (Phạm Thận Duật Reference Phạm1856, 26a, passim). He recorded what he read on steles and temple inscriptions. He drew pictures of waterwheels and locals, and seems to have learned a good deal of the local spoken language and script. The author was an attentive observer of local life. At the same time, Phạm integrated local knowledge and personal observation into existing systems of knowledge, by relying largely on published texts to mediate what he observed and testing received knowledge to determine what should be kept and what discarded. In this way, he was not dissimilar to European colonial medical specialists who selectively incorporated indigenous knowledge into European medical culture, formulating what they learned from locals into a language that would make sense to their metropolitan interlocutors.Footnote 33 Phạm was participating in a process of negotiation between local knowledge, customs, and techniques and a culture of knowledge that drew on the classical canon and evidentiary scholarship.

Conclusion: A Borderless World of Books

Phạm Thận Duật's work of transmitting and producing knowledge about the Nguyễn hinterlands enabled him to return to the capital, Huế, in 1878 and work in the highest offices of the central government. His scholarly acumen was recognized through appointments as tutor to Emperor Đồng Khánh (r. 1885–89), director of the College of the Sons of State (Quốc Tử Giám 國子監), and editor at the State History office (Quốc Sử Quán). Phạm contributed to Khâm Định Việt Sử Thông Giám Cương Mục 欽定越史通鑑綱目, an imperially sponsored history. In 1882–83, he was entrusted to go to Tianjin, China, on a diplomatic mission to seek help in dealing with French incursions.Footnote 34 He represented Vietnam at the signing of the Treaty of Huế (June 6, 1884, also known as the Patenôtre Treaty), which established the French protectorate of Vietnam. His role in ratifying this treaty did not save his life; in 1885, Phạm attempted to join the Cần Vương movement to restore power to the emperor, but was captured by the French, stripped of his titles, and sent to Côn Đảo prison for political prisoners. He died en route to prison in Tahiti. But to fully understand Phạm we must look back to the systems of knowledge and academic approaches that shaped his worldview.

Recent works in Vietnamese studies have shown that no one way of “being Vietnamese” was more authentic than any other, some by taking seriously Vietnamese scholars’ commitment to classical learning, and others by recognizing that there were multiple ways of being Vietnamese in particular “surfaces” of time and place. Both have moved the field away from the schematic and facile separation of Southeast Asian structures and the influence of the “Chinese model.” In Phạm's time, a relatively new Nguyễn dynasty was still actively engaged in consolidating and expanding its control over a Vietnamese state of unprecedented proportions, dispatching Phạm to the northwestern highlands. Both a representative of Nguyễn colonialism and a victim of French colonialism, a classically trained scholar and an innovative thinker, Phạm defies easy categorization. When we try to reconstruct his intellectual world, we see that the north-south binaries that preoccupy modern historians mattered not a whit. Although Phạm was producing knowledge useful to the Nguyễn state, he was doing so within a borderless world of books.

Revisiting the work of the northern literatus Phạm Thận Duật shows that Vietnamese scholars were neither second-rate nor passive scholars, but active participants in a transregional community of inquiry. They produced knowledge by testing and expanding received tradition, benefiting from Chinese sources while critiquing them and supplementing them with a rich local tradition outside of the view of Chinese scholars. Phạm Thận Duật's Hưng Hóa Gazetteer affirms that Vietnamese intellectuals had their own epistemic agency to assess, contest, and produce knowledge within the “Confucian commonwealth.”

Acknowledgments

This article was much improved by comments from Christopher Moore, John Phan, Jessamyn Abel, Maia Ramnath, Anatoly Detwyler, Nhung Tuyet Tran, On-cho Ng, Hoai Tran, and Nathan Vedal. Kwok-leong Tang led me to Cai Tinglan and served as my sounding board. The Institute for Arts and Humanities at Penn State and the American Council of Learned Societies Luce Postdoctoral Fellowship supported research for this project. I would like to especially thank the three anonymous readers who pushed me to strengthen and clarify my argument. The article is much stronger thanks to their insight.