Introduction

Globally, approximately 10% of women in high-income countries (HIC) and more than 25% in low-and-middle-income countries (LMIC) are affected by mental disorders in the perinatal period (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, De Mello, Patel, Rahman, Tran, Holton and Holmes2012; Howard et al. Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; World Psychiatric Association, 2015). Although the focus of perinatal mental health research and intervention has been on depression, particularly postnatal depression, there is growing evidence of the importance of other primary and comorbid disorders, particularly anxiety disorders (Roos et al. Reference Roos, Faure, Lochner, Vythilingum and Stein2013; Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Chenausky and Freeman2014; Howard et al. Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; Biaggi et al. Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante2016). In South Africa, diagnostic prevalence rates of antenatal depression range between 22% and 34% and antenatal anxiety disorders between 3% and 30%, which is comparable to other LMIC settings (Rochat et al. Reference Rochat, Tomlinson, Bärnighausen, Newell, Stein and Jean2011; van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Myer, Onah, Tomlinson, Field and Honikman2016, Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017).

The perinatal period is recognised as a time of increased risk for onset of mental health problems (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NICE), 2014; Meltzer-Brody & Brandon, Reference Meltzer-Brody and Brandon2015). The impact of such morbidity includes adverse outcomes for pregnancy, disrupted maternal functioning, disordered mother-infant interactions; impaired growth and development as well as increased psychological, behavioural and cognitive difficulties in offspring (Glover & O'Connor, Reference Glover and O'Connor2002; Hanlon et al. Reference Hanlon, Medhin, Alem, Tesfaye, Lakew, Worku, Dewey, Araya, Abdulahi, Hughes, Tomlinson, Patel and Prince2009; Manikkam & Burns, Reference Manikkam and Burns2012; Parsons et al. Reference Parsons, Young, Rochat, Kringelbach and Stein2012; Brittain et al. Reference Brittain, Myer, Koen, Koopowitz, Donald, Barnett, Zar and Stein2015; Gentile, Reference Gentile2015; Herba et al. Reference Herba, Glover, Ramchandani and Rondon2016). There are increases in infant mortality (Stein et al. Reference Stein, Pearson, Goodman, Rapa, Rahman, McCallum, Howard and Pariante2014) and maternal morbidity and mortality through increased risk of maternal substance abuse, heightened vulnerability to domestic violence and accompanying homicide and comorbid physical illnesses such as HIV (Langer et al. Reference Langer, Meleis, Knaul, Atun, Aran, Arreola-Ornelas, Bhutta, Binagwaho, Bonita, Caglia, Claeson, Davies, Donnay, Gausman, Glickman, Kearns, Kendall, Lozano, Seboni, Sen, Sindhu, Temin and Frenk2015). Mental disorders during the perinatal period are also associated with a higher prevalence of maternal suicidal ideation and behaviour (Onah et al. Reference Onah, Field, Bantjes and Honikman2016a; Orsolini et al. Reference Orsolini, Valchera, Vecchiotti, Tomasetti, Iasevoli, Fornaro, De Berardis, Perna, Pompili and Bellantuono2016). These consequences are heightened in contexts of chronic poverty and social adversity, where there are multiple contributing risk factors and stressors (Howard et al. Reference Howard, Molyneaux, Dennis, Rochat, Stein and Milgrom2014; Langer et al. Reference Langer, Meleis, Knaul, Atun, Aran, Arreola-Ornelas, Bhutta, Binagwaho, Bonita, Caglia, Claeson, Davies, Donnay, Gausman, Glickman, Kearns, Kendall, Lozano, Seboni, Sen, Sindhu, Temin and Frenk2015; van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Myer, Onah, Tomlinson, Field and Honikman2016).

In LMIC, there are considerable gaps in the detection, treatment and care of common perinatal mental disorders (CPMD) and approximately 80% of cases remain unrecognised and untreated (Condon, Reference Condon2010). This may be due to resource constraints affecting the health care system, lack of adequate training for health workers in detecting and treating mental disorders, high patient volumes in primary health settings which make it difficult for health workers to spend time on screening and counselling, lack of referral pathways for mental health care and the competing burden of high-prevalence diseases such as TB and HIV (Saxena et al. Reference Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp and Whiteford2007; Draper et al. Reference Draper, Lund, Kleintjes, Funk, Omar and Flisher2009; Petersen et al. Reference Petersen, Bhana, Campbell-Hall, Mjadu, Lund, Kleintjies, Hosegood and Flisher2009; Kakuma et al. Reference Kakuma, Minas, van Ginneken, Dal Poz, Desiraju, Morris, Saxena and Scheffler2011; Lund et al. Reference Lund, Kleintjes, Cooper, Petersen, Bhana and Flisher2011, Reference Lund, Kleintjes, Kakuma and Flisher2010). Poverty acts as a barrier to receiving mental health care for women who have to leave their obligations at home and expend additional resources to access such care, often at a separate site to antenatal or postnatal services (Hock et al. Reference Hock, Or, Kolappa, Burkey, Surkan and Eaton2012; Benatar, Reference Benatar2013).

In South Africa, social and economic disparities affect the health care system and public sector primary health clinics often operate with minimal resources, while experiencing high patient volumes (Benatar, Reference Benatar2013). In such settings, where resources are scarce and with a paucity of specialist mental health care, there has been a call for task shifting of routine activities such as mental health screening to primary health staff and community health workers (CHWs). Task shifting may facilitate the integration of mental health services into primary care and more efficient use of human resources, which could result in greater detection and service coverage of the population (Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012). However, it is important that screening tools used by non-specialist health workers and CHWs in primary health care contexts are appropriately developed or adapted for their skill level as there may be literacy and numeracy barriers (Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012). In particular, Likert scoring systems might not be feasible or acceptable for use in settings where those conducting screening and/or those being screened have limited numeracy (Moss et al. Reference Moss, Larouche, Assah, Oyeyemi, Adedoyin, Kasoma, Aryeetey, Lambert, Ocansey, Akinroye, Prista, Sallis, Cain, Conway, Bartels, Kolbe-Alexander, Tremblay, Gavand and Onywera2016; Afulani et al. Reference Afulani, Diamond-Smith, Golub and Sudhinaraset2017; Nyongesa et al. Reference Nyongesa, Sigilai, Hassan, Thoya, Odhiambo, Van De Vijver, Newton and Abubakar2017). In order to introduce routine screening into such settings, there is a need for pragmatic screening instruments that are short, quick to administer and easy to score and interpret (Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012).

One way to address these challenges is to generate from within LMICs, evidence-based screening instruments with adequate psychometric validity (Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012; Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Scott, Hung, Zhu, Matthews, Psaros and Tomlinson2013). The tools would need to have high sensitivity and specificity in order not to overburden the health care system with false-positive cases. For use in real-world settings, and in order to be clinically useful, these tools would further need to fulfil the criteria of validity, including cultural and cognitive validity (Tsai et al. Reference Tsai, Scott, Hung, Zhu, Matthews, Psaros and Tomlinson2013). These needs were experienced by the Perinatal Mental Health Project (PMHP), which has been operating and supporting integrated mental health services within maternity service settings in Cape Town since 2002 (Honikman et al. Reference Honikman, van Heyningen, Field, Baron and Tomlinson2012). The PMHP hosted this study, which aimed to develop a psychometrically valid, ultra-short screening tool to detect antenatal depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation in South Africa.

Methodology

Setting

This cross-sectional study was undertaken at the Hanover Park Midwife Obstetric Unit (MOU), Cape Town, South Africa, which provides primary-level maternity services. Hanover Park has a population of about 35 000 people (Statistics South Africa, 2013) and is a community characterised by high levels of poverty and community-based gang violence. In this community, roughly 61% of adults do not have a regular income and less than 20% of adults have completed high school (Moultrie, Reference Moultrie2004).

General mental health services are provided by two psychiatric nurses to outpatients at the Hanover Park Community Health Clinic (CHC), adjacent to the MOU. A psychiatrist and intern clinical psychologist provide weekly consultations at the CHC. The CHC's casualty unit manages psychiatric emergencies and makes referrals to district or tertiary level hospitals. At the time of data collection, there were no specific mental health screening and support services for pregnant women.

Participants

Pregnant women arriving at the Hanover Park MOU for their first antenatal visit were invited to participate in the study. Women included in the study were 18 years or older, pregnant, willing to provide informed consent to participate and able to understand the nature of the study. Exclusion criteria were diagnosed with a current psychotic disorder or high-risk suicidal ideation or behaviour on the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) Plus.

Approval for the study was granted by the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Health Research Committee and the University of Cape Town (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research and Ethics Committee (HREC REF: 131/2009).

Instruments used

A demographics questionnaire was administered that included questions on age, language, education level, socioeconomic status, HIV status, gestation, gravidity and parity. Commonly used mental health screening tools were used to screen for antenatal depression and anxiety:

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) has been found to be a reliable instrument in screening for antenatal depression (Murray & Cox, Reference Murray and Cox1990) and has been validated for use in a wide range of settings including South Africa (Eberhard-gran et al. Reference Eberhard-gran, Eskild, Tambs, Opjordsmoen and Samuelsen2001). A cut-off score of ⩾13 on the EPDS has shown a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 77% for major and minor depression combined, in a South African setting (Lawrie et al. Reference Lawrie, Hofmeyer, de Jager and Berk1998).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was developed for detection of depression in primary care settings and has been tested for validity among diverse populations (Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2001) including in South Africa (Cholera et al. Reference Cholera, Gaynes, Pence, Bassett, Qangule, Macphail, Bernhardt, Pettifor and Miller2014; Bhana et al. Reference Bhana, Rathod, Selohilwe, Kathree and Petersen2015). It has been validated in both antenatal and postnatal populations in various settings (Sidebottom et al. Reference Sidebottom, Harrison, Godecker and Kim2012; Zhong et al. Reference Zhong, Gelaye, Rondon, Sánchez, García, Sánchez, Barrios, Simon, Henderson, May Cripe and Williams2014; Barthel et al. Reference Barthel, Barkmann, Ehrhardt, Schoppen, Bindt, Appiah-Poku, Baum, Te Bonle, Burchard, Claussen, Deymann, Eberhardt, Ewert, Feldt, Fordjour, Guo, Hahn, Hinz, Jaeger, Koffi, Koffi, Kra, Loag, May, Mohammed, N'Goran, Nguah, Osei, Posdzich, Reime, Schlüter, Tagbor and Tannich2015).

The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) has agreeable sensitivity and specificity in detecting depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder and social phobia and is a useful screening measure for antenatal depression and anxiety disorders (Kessler et al. Reference Kessler, Andrews, Colpe, Hiripi, Mroczek, Normand, Walters and Zaslavsky2002). A score of ⩾21.5 (sensitivity 73%; specificity 54%) has been determined as the best screening cut-off for diagnosed depressive and anxiety disorders amongst pregnant women in South Africa (Spies et al. Reference Spies, Stein, Roos, Faure, Mostert, Seedat and Vythilingum2009).

The Whooley questions comprise two depressive symptom questions and an optional ‘help’ question which may be asked if the woman responds positively to either of the first two questions (Whooley et al. Reference Whooley, Avins, Miranda and Browner1997). These questions have been advocated by the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for perinatal mental health in the UK (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NICE), 2014). The Whooley questions offer a relatively quick and convenient way of case-finding for non-specialist health workers in primary care settings and have been validated for use in detecting antenatal depression amongst low-income women in the South African setting (Marsay et al. Reference Marsay, Manderson and Subramaney2017).

The Generalised Anxiety Scale (revised) (Generalised Anxiety Disorder, GAD-2) is a 2-item form of the GAD-7. It has not yet been validated for use in South Africa or with antenatal populations but is regarded as being a clinically useful, short screening tool for GAD and other anxiety disorders in primary care (Kroenke et al. Reference Kroenke, Spitzer and Williams2007). Recently, these questions have been advocated as an adjunct to screening for depression by UK's NICE guidelines for perinatal mental health (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (NICE), 2014).

A number of psychosocial risk questionnaires were used to screen for common risk factors associated with CPMD (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Myer, Onah, Tomlinson, Field and Honikman2016, Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017). These included the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-2) (Straus & Douglas, Reference Straus and Douglas2004), the US Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM) (Blumberg et al. Reference Blumberg, Bialostosky, Hamilton and Briefel1999), the List of Threatening Experiences (LTE), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) (Zimet et al. Reference Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet and Farley1988), as well as the PMHP Risk Factor Analysis (RFA) tool. The RFA measures 11 risk factors including satisfaction with the current pregnancy, experience of difficult life events, the presence of a partner, perceived emotional support from partner, experience of current domestic violence, perceived emotional and/or practical support from family and friends, prior history of abuse (physical, verbal or sexual), quality of relationship with own mother, past experience of miscarriage, abortion, stillbirth or death of a child, and self-reported history of mental health problems (Honikman et al. Reference Honikman, van Heyningen, Field, Baron and Tomlinson2012).

Inclusion of the abovementioned instruments was based on screening tools meeting as many of the following criteria as possible: prior published evidence of validation against clinical diagnosis, prior use in South Africa or in LMIC and/or low-resource settings, prior use in primary care settings and evidence of validity for use with a perinatal population. All screening tools were professionally translated and back-translated from English into Afrikaans and isiXhosa, which are the three most commonly spoken languages in the Hanover Park community.

The Expanded Mini Plus Version 5.0.0 was used as the clinical diagnostic interview (Sheehan et al. Reference Sheehan, Lecrubier, Sheehan, Amorim, Janavs, Weiller, Hergueta, Baker, Dunbar and Harnett Sheehan1998). The MINI Plus, which contains modules for the major axis I psychiatric disorders according to the DSM-IV TR, covers a broad range of disorders yet is relatively quick and easy to administer. The MINI Plus has been validated for use in South Africa (Kaminer, Reference Kaminer2001) and is available for administration in English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa (Myer et al. Reference Myer, Smit, Le Roux, Parker, Stein and Seedat2008; Spies et al. Reference Spies, Stein, Roos, Faure, Mostert, Seedat and Vythilingum2009).

Data collection

A research assistant and mental health officer were appointed to collect data and provide counselling. The research assistant was trained to recruit women, administer the screening battery and manage the study database. The mental health officer was a qualified, registered counsellor and was trained to administer the MINI Plus diagnostic interview as well as to counsel women who met the criteria for CPMD after screening. A clinical psychologist supervised both these staff. Health care staff at Hanover Park MOU received maternal mental health training to sensitise them to the mental health needs of their patients. An initial pilot study was conducted to determine the feasibility and acceptability of recruitment and screening for the staff and patients at the MOU.

Data were collected by sampling every third woman presenting for her first antenatal visit at the Hanover Park MOU between 22 November 2011 and 28 August 2012. The study was verbally explained to potential participants and written or verbal informed consent was obtained. The research assistant administered a demographics questionnaire followed by the battery of symptom and psychosocial risk screens. The mental health officer then administered the MINI Plus. The order of administration of screening tools was not varied. Women were offered refreshments and a place to rest between the screening questionnaires and the MINI assessment. Women were not financially compensated for their participation.

Referral for severe mental illness

Referral protocols were established with the MOU and CHC for women who required psychiatric intervention. Women diagnosed with severe psychopathology, such as schizophrenia, bi-polar mood disorder or psychosis, or who presented a high risk for suicide on the MINI Plus, were excluded from further screening at this point and referred to specialist care according to standard care protocols for the MOU and CHC. Women diagnosed with a common mental disorder such as major depressive episode (MDE) or an anxiety disorder on the MINI Plus, or with an EPDS cut-off score of ⩾13, were offered a counselling appointment with the mental health officer.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata v 13.1. The internal consistency and scale reliability of assessment tools were previously assessed using Cronbach's alpha statistics (Cronbach, Reference Cronbach1951), and were found to range from good to acceptable (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Tomlinson, Field and Myer2018). Descriptive measures were used to describe the sample and analyse socio-demographic variables and their associations with MDE and anxiety diagnoses, using non-parametric tests, the Wilcoxon sum of rank test, the Fisher exact test and the two-sample t test.

Initially, all screening tools in their entirety were analysed against diagnostic data using receiver operating curve (ROC) statistics to analyse their performance in detecting antenatal MDE and anxiety disorders. A detailed comparison of the psychometric performance of these screening tools has been described in detail elsewhere (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Tomlinson, Field and Myer2018). Following this, an item-by-item analysis of individual MDE and anxiety symptom-screening items were conducted using simple multiple logistic regression to determine which items were the best predictors of MDE and anxiety diagnoses. Significant items, those with a p-value < 0.05 and which indicated a change in pseudo-r 2 value >0.01, were noted. Significant items were then added to a multiple logistic regression model by systematically adding or subtracting these to determine which items were the best combined predictors for MDE and anxiety diagnosis: i.e. which combined items (2 at first, then 3, then 4 items) improved the model by increasing the value of pseudo r 2 > 0.01 while maintaining p < 0.05. Once the items were identified, their content was examined and duplicate items were removed. Two suicidal ideation items (from the EPDS and PHQ9) were examined against MINI criteria for suicidal ideation and behaviour. Best-performing items with Likert-type scoring were binarised to create a uniform scoring system for the potential new tool. The Likert scoring and binarised scoring versions of items were compared against each other using diagnostic data to ensure that their performance in predicting the variables of interest were consistent and comparable.

Finally, the best combinations of items were analysed using ROC analysis of the area under the curve (AUC) to determine which set of items were the best predictors of MDE and anxiety diagnosis. Detailed ROC analysis output was used to evaluate the cut-point of the best-performing combined items that yielded optimal sensitivity and specificity and number of cases correctly classified.

Individual items from psychosocial risk screening questionnaires were also analysed using the same methodology described above. These items were then systematically added (item-by-item) to the combined, best-performing symptom-screening items to see whether they significantly enhanced the predictive value of the new combined screening tool. They were further analysed as a separate, adjunct-screening tool to the symptom-screening tool using multiple logistic regression and ROC analysis.

Results

Demographic description of the sample

A total of 376 pregnant women participated in the study. The mean age of the sample was 27 years, with a mean education level of Grade 10. Most (90%) of women were married or in a stable relationship, over half were in the second trimester of their second pregnancy and although 63% of pregnancies were unintended, 78% of the sample was reportedly pleased to be pregnant. The unemployment rate was 55%, with 43% of women living below the Statistics South Africa (SSA) poverty line (Statistics South Africa, 2015) and 42% reporting food insecurity (see Table 1). Significant associations were found between MDE and anxiety diagnoses with food insecurity, having more than one child, having an unintended and unwanted pregnancy, suicidal ideation and behaviour, current use of substances other than alcohol as reported on the MINI, perceived lack of partner support, current experience of domestic violence or of past physical, sexual or emotional abuse, self-reported history of mental health problems and experience of major, adverse life events in the past year. These associations have been described and discussed in detail elsewhere (Onah et al. Reference Onah, Field, Bantjes and Honikman2016a, Reference Onah, Field, van Heyningen and Honikmanb; van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Myer, Onah, Tomlinson, Field and Honikman2016, Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017; Field et al. Reference Field, Onah, van Heyningen and Honikman2018).

Table 1. Demographics of the sample according to diagnostic categories.

a Two-sample t test.

b Fisher's Exact test.

c The term ‘Coloured’ refers to a heterogeneous group of people of mixed race ancestry that self-identify as a particular ethnic and cultural grouping in South Africa. This term, and others such as ‘White’; ‘Black/African’ and ‘Indian/Asian’, remain useful in public health research in South Africa, as a way to identify ethnic disparities, and for monitoring improvements in health and socio-economic inequity after the abolishment of Apartheid in 1994.

*Shows significance at p < 0.05; **Shows significance at p < 0.001.

MINI diagnoses and comorbidity

There were 81 women (22%) who were diagnosed with current MDE and 86 (23%) who had diagnosed anxiety disorders [PTSD (11%), social phobia (7%), specific phobia (6%), OCD (4%), panic disorder (3%); generalised anxiety disorder (2%) and agoraphobia (0.3%)] (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017). There was substantial comorbidity between diagnoses of MDE and anxiety disorders. Of those with MDE, 56% were also diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. There were 69 women (18%) who expressed suicidal ideation and behaviour, however, 37 [about half of those with expressed suicidal ideation and behaviour (SIB)] were suicidal without a diagnosis of MDE or anxiety (Onah et al. Reference Onah, Field, Bantjes and Honikman2016a, Reference Onah, Field, van Heyningen and Honikmanb). Fifty-seven women (15%) reported current, harmful use of alcohol and/or other substances on the MINI.

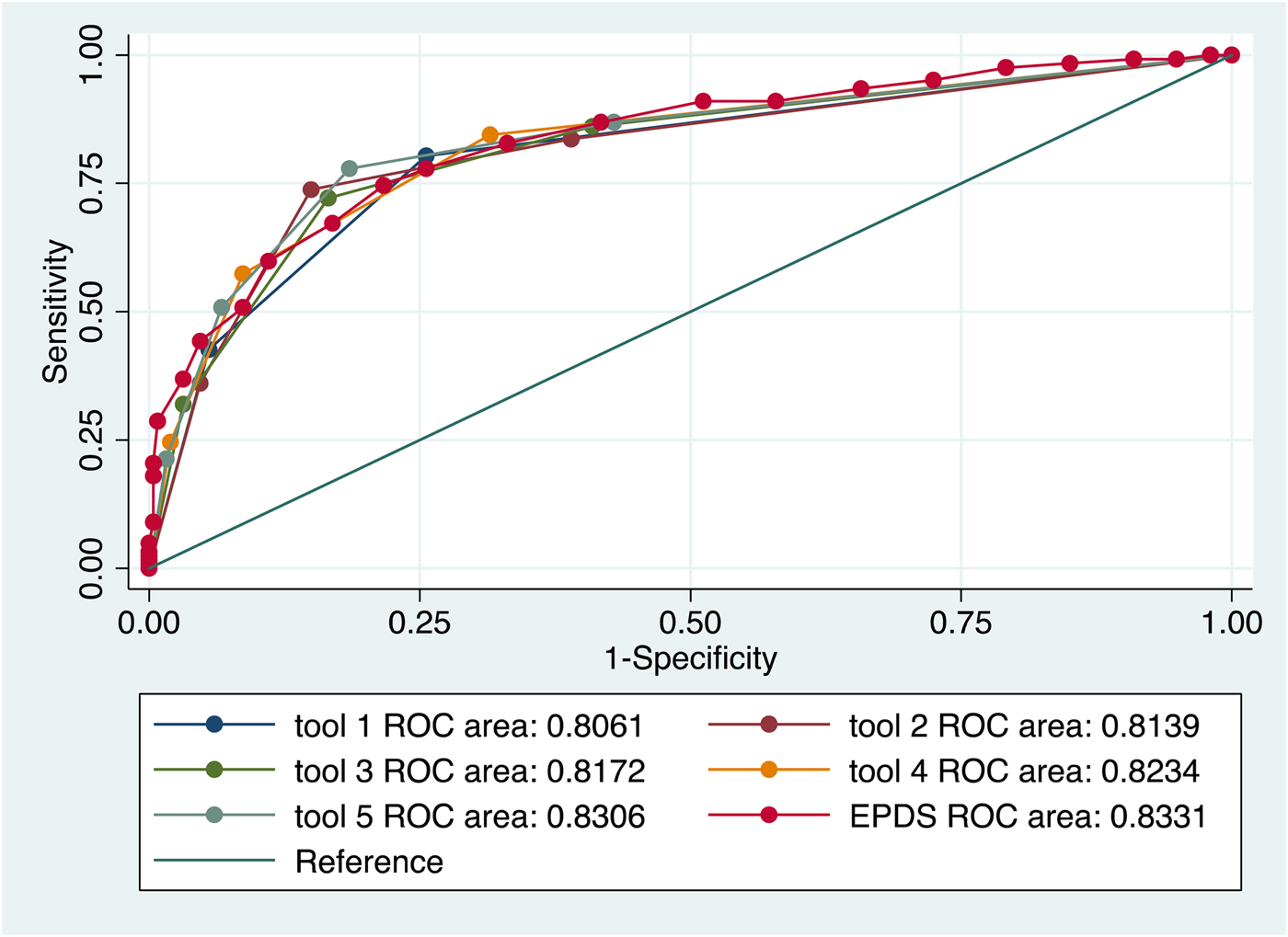

Results of logistic regression

Previous analysis comparing the psychometric performance of screening tools found that the two Whooley questions performed as well as the longer EPDS, K10 and PHQ9 in detecting symptoms of MDE and anxiety (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Tomlinson, Field and Myer2018). We used these results as a starting point to conduct the primary logistic regression to identify screening items that were independently predictive of MDE and anxiety diagnoses (see Table 2). Different combinations of the best-performing individual items yielded various iterations of a potential new screening tool (see Table 3). There were five variations of this potential new tool in the final analysis. Results from the ROC analysis of these variations against MDE and anxiety diagnosis are displayed in Table 4. All versions of the potential new tool had AUCs over 0.80. The sensitivity of the tools varied between 57% and 80%, and specificity between 74% and 91%, and the four-item version of the new screening tool performed with greater sensitivity (78%) and specificity (82%) than the EPDS (sensitivity 75%; specificity 78%) (see Fig. 1).

Table 2. Top-performing symptom-screening questions that were independently predictive of MDE and/or anxiety diagnosis.

Table 3. Analysis of screening items against separated diagnostic categories.

a Binarised version.

Table 4. ROC analysis comparing the performance of variations of the proposed screening tool, with the EPDS, against MINI diagnosis of MDE and/or anxiety disorders.

a Binarised version.

Fig. 1. Performance of various iterations of the new screening tool compared to the EPDS in detection of MDE and anxiety disorder diagnoses.

Risk factors

There were five psychosocial risk factor items that were strongly associated with MDE and anxiety diagnosis. These were, in order of significance: a self-reported history of mental health problems; experience of difficult life events in the past year; experience of abuse (physical, emotional, sexual or rape) in the past; experience of current domestic violence from a partner or someone else in the household; and lack of perceived support and comfort from a ‘special person’.

Although individual risk factor items had significant predictive value, adding these to the combined, symptom-screening items did not significantly enhance the psychometric performance of the model. There was no significant improvement in the outcome of the multiple logistic regression model, nor the AUC of the ROC analysis when risk factor items were added to symptom screening items. However, when the best-performing psychosocial risk screening items were combined as a separate, ‘risk screening tool’ associated with MDE and anxiety diagnosis, the combined items yielded a fair AUC of 0.73 with a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 64% at a cut-point of ⩾2 risk factors.

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that symptoms of MDE and anxiety and suicidal ideation in low-resource settings can be detected using an ultra-short, binary-scoring screening tool. The performance of this tool is comparable to longer screening tools and has several advantages.

Firstly, the brevity and ease of scoring of the tool may be beneficial for use in busy, low-resource settings with high volumes of service users. In these settings, the time taken to administer and score mental health screening instruments is critical and an ultra-short tool with a binary scoring system is likely to be more feasible and acceptable, especially for those with limited numeracy (Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012).

The screening items of the tool, which included an item about depressed mood, one about anhedonia, one about anxiety symptoms and one asking about suicidal ideation were highly effective at predicting CPMD. The second advantage of this tool is that it includes an item asking about symptoms of anxiety. Anxiety during pregnancy has increasingly been shown to be of concern as it is highly prevalent, is a strong predictor for postnatal psychiatric disorders and has a significant deleterious effect on maternal functioning and on child health and development (Biaggi et al. Reference Biaggi, Conroy, Pawlby and Pariante2016; Coelho et al. Reference Coelho, Murray, Royal-lawson and Cooper2011; van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017). Screening for symptoms of anxiety during pregnancy may be as important as screening for symptoms of depression, especially when the diagnostic prevalence of these disorders is equally high (Howard, Reference Howard2016; van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Myer, Onah, Tomlinson, Field and Honikman2016, Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Myer, Onah, Field and Tomlinson2017).

Thirdly, although the initial aim in developing our screening tool was to detect CPMD, we made the decision to include an item on suicidal ideation, as suicide is a leading cause of maternal mortality (Oates, Reference Oates2003; Orsolini et al. Reference Orsolini, Valchera, Vecchiotti, Tomasetti, Iasevoli, Fornaro, De Berardis, Perna, Pompili and Bellantuono2016). Also, analysis of the dataset showed that a large proportion of women with suicidal thoughts and/or behaviour had neither depression nor anxiety diagnoses (Onah et al. Reference Onah, Field, Bantjes and Honikman2016a). SIB that occurs outside of the context of depression and anxiety diagnosis is an important public health issue, and has been described in greater detail in another paper arising from the same dataset (Onah et al. Reference Onah, Field, Bantjes and Honikman2016a). The inclusion of SIB item in our ultra-short tool offers an opportunity to provide care for these high-risk women who may otherwise remain undetected. Furthermore, we made the decision to include the SIB item because it was independently predictive of MDE and anxiety diagnosis. This also follows on from recommendations made by other researchers in South Africa who examined ultra-short versions of the EPDS to screen for depression amongst high-risk pregnant women and similarly found high rates of suicidal ideation. They also recommended the inclusion of item 10 of the EPDS on the basis of its performance in predicting perinatal depression (Rochat et al. Reference Rochat, Tomlinson, Newell and Stein2013).

The psychometric properties of our new screening tool for CPMDs are comparable to longer screening tools such as the EPDS, PHQ9 and K10, all of which demonstrate moderate to high performance (AUC 0.78–0.85) (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Tomlinson, Field and Myer2018). However, the fourth advantage of our tool over existing tools is its sensitivity and reliability. Such properties may facilitate widespread screening, especially where there are resource barriers to screening, as mentioned previously. A high level of sensitivity in a screening tool is important for first-level screening purposes, however in resource-constrained areas this needs to be balanced with adequate specificity so as not to flood the system with false positives. The sensitivity (78%) and specificity (82%) of our tool in detecting MDE and anxiety disorders seems favourable compared to the EPDS (75%; 78%) and the PHQ9 (66%; 76%), as well as ultra-short versions of these: the 3-item EPDS (70%; 77%), the PHQ2 (75%; 69%) and the Whooley questions (66%; 87%) (van Heyningen et al. Reference van Heyningen, Honikman, Tomlinson, Field and Myer2018).

This screening tool may be most suitable for application as an initial screen, forming the first part of a staged assessment. Where resources are available, more qualified care workers may thereafter conduct further in-depth screening with other more complex tools and initiate appropriate referrals. There is also potential to adapt and test the tool for mobile technology platforms, where it can be self- administered, thereby providing an assessment of mental health problems outside of clinical settings.

Limitations of the study

Although the findings of this study show promise, there are several limitations. The screening tools were administered in the same order, which may have influenced women's answers. Screening items relied on self-report and therefore may have been subject to recall bias. As this was a cross-sectional study, we were not able to measure the tools’ performance over time or in different pregnancy trimesters. The screening tools had different recall periods, which may have caused the participants some confusion. In order to standardise the scoring system, certain Likert-type scoring items were adapted to be binary scoring. Although this was done for ease of use in clinical application, this may have affected the accuracy of the scoring.

At the time of writing, our proposed new symptom-screening tool appears to be one of the most suitable ultra-short screening tools to detect CPMD in low-resource settings in South Africa. Its psychometric performance compares to other ultra-short screening tools and to longer tools and it shows promise for clinical application as an initial screen.

General recommendations

The proposed new screening tool is depicted in Table 5. It has two distinct sections: Section A screens for MDE and anxiety symptoms and/or suicidal ideation and an optional Section B which screens for psychosocial risk. The screening tool depicted in this table includes modifications to certain items: to standardise the screening items, those with Likert-type scoring have been binarised (see psychometric data above) and recall periods have been standardised for the past month (requiring item 3 to change from 2 weeks and item 4 to change from the past 7 days). On the recommendation of experienced, local, mental health practitioners, the EPDS10 question asking about suicide has been re-worded from its original format to improve face validity.

Table 5. Proposed new screening tool for CPMD.

b(E.g. Death of a close relative; serious injury/illness/assault of a close relative; major financial crisis; something valuable lost/stolen; serious problem with a close friend/neighbour/relative; problems with police/court appearance)

Before this tool may be incorporated into maternity care or other screening protocols, further research is required to adapt and validate the tool with a standardised recall period as well as for culturally congruent language usage using cognitive interviewing techniques or other appropriate methods. Secondly, the tool should be field-tested for feasibility and acceptability in a range of settings and across sectors, where pregnant and post-partum women access care for themselves and/or their infants, including but not limited to the antenatal, postnatal and infant care settings and the social development sector. Third, the tool could be evaluated for other vulnerable populations such as adolescents or migrant/refugee women; and through different modes of administration, including digital platforms. Lastly, there is scope for further research on the feasibility and acceptability of the psychosocial risk-factor component as an adjunct to the symptom-screening tool in a range of resource-constrained settings.

Recommendation on the SIB item

Previous studies have cautioned that item 10 of the EPDS, asking about suicidal ideation, is rarely used in settings where resources to respond are limited (Akena et al. Reference Akena, Joska, Obuku, Amos, Musisi and Stein2012). Potential pitfalls regarding the inclusion of this screening item in a population with high SIB include flooding a poorly resourced system with false positive cases as well as the associated stigma and discrimination for women labelled with SIB. It may, therefore, be useful to investigate the inclusion of the SIB item by conducting further research and potentially expanding the item to ask about intent, plans for self-harm, and history of SIB. This may serve to increase the specificity of the item and mitigate the potential pitfalls described above. It is usually recommended that screening with ultra-short tools be followed with more detailed, in-depth screening in order to ensure more specific detection and targeted management of SIB cases (Akena et al. Reference Akena, Joska, Obuku, Amos, Musisi and Stein2012; Oates, Reference Oates2003).

Recommendations on risk factor screening

Recent recommendations by global experts for perinatal mental health advise that interventions in LMICs should include screening for and addressing risk factors and associated problems (Austin, Reference Austin2014; Meltzer-brody et al. Reference Meltzer-Brody, Howard, Bergink, Vigod, Jones, Munk-Olsen, Honikman and Milgrom2018). Risk factor screening may be conducted after symptom screening has occurred, or may be included in the development of screening tools which assess both symptoms and risk (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Colton, Priest, Reilly and Hadzi-Pavlovic2011; Somerville et al. Reference Somerville, Dedman, Hagan, Oxnam, Wettinger, Byrne, Coo, Doherty and Page2014). Although adding psychosocial risk factors does not enhance the predictability of our tool, adding risk factors as an adjunct to symptom screening, may be a useful way to identify women experiencing psychosocial stressors that increase risk for CPMD (Jewkes et al. Reference Jewkes, Dunkle, Koss, Levin, Nduna, Jama and Sikweyiya2006; Austin, Reference Austin2014). Screening for risks may help to identify women who require specific interventions and facilitate or rationalise the allocation of resources for particular problems (e.g. partner violence, food insecurity or improper nutrition, substance use). Lastly, risk screening as an adjunct to symptom screening may assist within mental health counselling as a form of assessment and facilitating initial engagement work (Steering Group for Perinatal Mental Health, 2017; Meltzer-brody et al. Reference Meltzer-Brody, Howard, Bergink, Vigod, Jones, Munk-Olsen, Honikman and Milgrom2018). Linked to this, any form of screening – whether for risk or symptoms or both, must take place as part of a well-articulated referral protocol with defined pathways to care. In this way, high-risk populations may efficiently be triaged to care, e.g. as part of a stepped care approach (Honikman et al. Reference Honikman, van Heyningen, Field, Baron and Tomlinson2012; Kagee et al. Reference Kagee, Tsai, Lund and Tomlinson2012).

Conclusions

In LMIC, where resources are scarce, using an ultra-short, binary-scoring screening tool may be a feasible and valid means to provide universal screening of pregnant women for CPMD. The inclusion of a question asking about suicidal thoughts appears to enhance the detection of women with CPMD and the detection of pregnant women who are suicidal without symptoms of CPMD. Using risk screening as an adjunct to symptom screening may be a useful way to allocate resources for early intervention or for preventing the development of mental disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the staff and study participants of Hanover Park Midwife Obstetric Unit as well as the Western Cape Department of Health. We are particularly grateful for assistance from Prof. Susan Fawcus, Ms Bronwyn Evans, Liesl Hermanus and Sheily Ndwayana. This work was supported by the South African Medical Research Council (S.H., grant no. N/A); Cordaid (S.H., grant no. N/A); The National Research Foundation of South Africa (T.vH., grant number VHYTHE001) and The Harry Crossley Foundation (T.vH., grant number VHYTHE001).

Declaration of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.