A distinguishing feature of the modern state is the broad scope of public goods and service provision. Beginning in the nineteenth century and accelerating in the twentieth, the state's core functions expanded into the domains of education, health care, and social welfare assistance.Footnote 1 This expansion of social services fundamentally altered the nature of government: whereas premodern states exploited and extracted,Footnote 2 modern states gradually began to provide and protect.Footnote 3 However, this shift in the scope of state services was unevenly distributed both spatially and temporally, especially in colonial territories. What explains the uneven reach and presence of social welfare in the colonial state? Why did colonial states expand social service provision in some areas but not others?

An influential strand of the literature argues that war played a central role in the expansion of the welfare state and the reduction of wealth inequality.Footnote 4 The introduction of mass mobilization required enlisting large segments of the population—often but not always conscripts. Concerns about military readiness and large numbers of widows, orphans, and disabled veterans after armistice incentivized states to expand social policies.Footnote 5 For example, in the United States, political parties competing for the votes of veterans promised substantial social aid and assistance.Footnote 6 In Britain, where conscription was introduced in March 1916, the public clamored for better social services, such as housing, in response to the havoc and destruction of World War I.Footnote 7 However, it is less clear whether the same pattern held in colonial territories. Standard accounts of warfare and welfare often overlook variation in social assistance outside the metropole, despite the enormous sacrifices made by colonial conscripts, particularly in World Wars I and II.

This paper examines the spatial variation in social and welfare provision by asking for whom warfare increased welfare. We argue that these spatial and group-based differences are a consequence of the bargaining disadvantages that marginalized groups face in compelling the state to provide rewards in return for military service. We build on but depart from the influential bellicist literature on the effects of war on state development by recognizing the powerful incentives that states have to shirk this basic bargain between rulers and the ruled in settler colonies.Footnote 8 Unlike taxation and conscription, which were essential to the war effort, the provision of social and welfare services requires large financial outlays with little immediate return to the state. States are therefore likely to shirk these significant costs unless the governed can hold the state accountable. Colonial subjects were less able than citizens to enforce this bargain because subjects lacked the mechanisms of accountability available to citizens.

We test this argument using new archival and geospatial data at the commune (third administrative) level from French Algeria in the early twentieth century. Following its conquest in 1830, Algeria became the largest and most important part of the French Empire, and contributed many soldiers to the French military in World Wars I and II. An estimated 172,000 Algerians fought in World War I,Footnote 9 the first mobilization to introduce mass conscription of Muslim subjects. Algerian units played a key role in blunting the initial German offensive in August 1914 and in the long years of trench combat that followed. By the end of the conflict, nearly 43,000 Algerian-born soldiers made the ultimate sacrifice for France. In World War II, the quick fall of the French military to the Nazis in 1940 meant that mobilization was more limited than during World War I. Nonetheless, after the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942, more than 134,000 Algerian-born soldiers were mobilized,Footnote 10 and an estimated 18,000 were killed liberating Europe.

Unlike other parts of the Empire, Algeria's three northern départements (first-level divisions) were administratively part of France after 1848.Footnote 11 Our research design exploits variation within this internal administrative structure. Although Algeria was technically as much a part of France as Corsica, Martinique, or Réunion, the systematic marginalization of Muslim Algerians meant that a highly unequal and exclusionary pattern of governance dominated local administration from conquest in 1830 until independence in 1962. In contrast, French citizens anywhere in Algeria were entitled to rights and privileges systematically denied to Algerian subjects. These privileges included political representation as well as access to public goods and services on par with those in the metropole. Colonial Algeria thus offers important inferential advantages in that it provides high-quality local data and holds constant the many country-level factors that often bedevil cross-national comparative research on war and the state.

Within this context, we compare levels of spending on pensions and social welfare before and after World War I using a difference-in-differences design. We find that despite the enormous sacrifices made by France's colonial subjects in World War I, public spending expanded much less in communes with a greater share of French subjects. We then supplement this analysis with a quantitative exploration of mechanisms. We show that communes with more subjects faced a subject penalty after mobilization, as proxied by lower rates of spending on public assistance, education, and sanitation. Greater wartime casualties, as proxied through the local cumulative share of subject casualties in World War I, are associated with lower rates of spending on education, but higher rates of spending on the police and road building. Together, these results underscore the uneven effects of wartime mobilization on the expansion of public assistance and services.

This paper contributes to a large literature on the effects of warfare on state development. The warfare–welfare literature has long stressed the transformational nature of World War I and especially World War II on the expansion of welfare in industrialized states such as Britain, Canada, France, Germany, and the United States.Footnote 12 These conflicts were global in terms of wartime labor contributions and the theaters of battle. Nonetheless, previous scholarship has tended to examine the consequences of war for welfare systems in the metropole rather than in nonsovereign territories, and for dominant social groups, often though not always white men, rather than marginalized groups that also made enormous sacrifices in both conflicts.Footnote 13

We highlight the importance of asking for whom warfare advanced welfare. Not all veterans mattered equally in the eyes of the state, nor did families impacted by the war enjoy equal bargaining power in the aftermath of conflict. Our paper suggests an important correction to theoretical accounts linking warfare and welfare by demonstrating how disparities in bargaining power of colonial subjects impacted the expansion of social services.Footnote 14

The Subject Accountability Disadvantage

Our argument about the subject accountability disadvantage begins with the observation that the successful prosecution of war requires the state to extract labor and wealth from its population. Because premodern and early modern states relied on a narrow segment of elite violence specialists (often mercenaries) and capital-holders for this labor and wealth, they could deliver concessions for military service and tax revenues on a private and limited basis.Footnote 15 As a result, powerholders like the Catholic Church, the landed aristocracy, and merchant capitalists acquired claims on the state for protection, stipends, preferential treatment, and political representation.

The advent of direct rule and advances in the technology of war in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries altered the relationship between the state and its population. Direct rule brought the state into contact with the mass public as never before, while new technology made it possible to mobilize and maintain large standing armies comprised of ordinary citizens.Footnote 16 These changes in the technology and character of war—in combination with the actual experience of conflict itself—had profound consequences for the expansion of the welfare state.Footnote 17

First and foremost, during wars of mass mobilization, societal consensus and mass compliance with conscription became integral to the war effort.Footnote 18 This created immense pressure to grant concessions in order to obtain the manpower necessary to prevail on the battlefield. While the state certainly had incentives to ensure compliance with conscription in peacetime as well, war lent new urgency to the issue of military readiness and manpower. As a result, the state extended new benefits such as universal suffrage.Footnote 19 In turn, these democratizing reforms paved the way for more individuals to articulate new demands on the state in the realms of social services, housing, and the economy.Footnote 20

Second, these demands were especially likely to manifest during and after war. The immense toll of war created new social and economic needs that differed from those of peacetime by orders of magnitude in scope and intensity. In addition to responding to the devastation of the economy, the destruction of housing, and surging unemployment, the state had to contend with the needs of large numbers of widows, orphans, and wounded and disabled veterans.Footnote 21 These enormous sacrifices in terms of lives and livelihoods lost also provided an opportunity for politicians to seek support at the ballot box by advocating for greater concessions from the state.

However, the state faced countervailing incentives that militated against the wholesale expansion of social services. Welfare provision entailed large fiscal outlays and costly investments in administrative capacity, adding to the pressure on state treasuries already straining under wartime fiscal demands. Moreover, financing these new activities required significant changes to the level and structure of taxation that in turn risked alienating the wealthy elite, who preferred a limited state.Footnote 22 Without further tax increases or new debt, balancing the budget required expenditure cuts, not new spending commitments. State expansion in the social welfare domain thus depended on the ability of the population to bargain with the state for concessions. This bargaining power was particularly strong in the aftermath of mass mobilization, given the enormous sacrifices made during wartime.

Given these countervailing incentives, our theory builds on existing arguments about state expansion and wartime sacrifice by recognizing the political disparities among veterans and their families that affect their ability to bargain with the state. We argue that, despite making comparable sacrifices, subjects of the colonial state faced a bargaining disadvantage relative to citizens in the colony that resulted in lower levels of social spending. We identify three interrelated sources of this disadvantage: the state had a weaker sense of obligation toward subjects; subjects lacked access to formal channels of political representation; and subjects were less able to credibly threaten violence against the state.

Compared to citizens, the state did not feel the same sense of obligation toward the wartime sacrifices of colonial subjects. For many if not most Europeans, colonial subjects were a foreign “other,” an out-group whose members had lower status than members of the in-group. Racist and paternalistic attitudes certainly played an important role in rendering colonial subjects less worthy and less deserving than white Europeans. So too did notions of national identity, which by definition excluded subjects while privileging the material interests and identity of citizens. Because subjects did not hold the same status as citizens, their sacrifices were discounted or given only token recognition. For these reasons, the metropole was less likely to be responsive to subjects’ demands for concessions from the state in recognition of their wartime service, and colonial citizens were similarly likely to oppose state expansion to subjects, even veterans, because citizens viewed more inclusive access to public goods and services as inimical to their own political interests.

Colonial subjects were also disadvantaged because they lacked access to formal institutional mechanisms of political accountability. In most colonies, the military and their intermediaries oversaw the local administration.Footnote 23 Although the degree of reliance on local authorities differed across empires,Footnote 24 in the absence of the credible threat of violence, there were few mechanisms available for locals to hold these “traditional” authorities accountable.Footnote 25 By contrast, colonial citizens enjoyed formal political and civil rights such as the extension of suffrage and often political representation in local legislative bodies. In the French Empire, these privileges extended to representation at the highest levels of national politics: colonial representatives held seats in the National Assembly starting in 1792.Footnote 26 By the late 1800s, a formal parliamentary lobby composed of parliamentarians as well as key members of the business elite worked to advance the interests of France's settlers and often tried to limit policies that they perceived as favorable to colonial subjects.Footnote 27

Formal representation in the French Empire was consequential both practically and symbolically. Practically, political representation gave colonial parliamentarians a seat at the table of national political power. Representation provided opportunities to make claims on the state, extract concessions from fellow lawmakers, and directly engage in the legislative process. Symbolically, formal political representation reaffirmed the status of the broader colonial community as part of the nation, just as the systematic exclusion of representatives for subjects served as a reminder of their diminished political influence and inferior legal status.

In the absence of formal political mechanisms, subjects in theory had the option of violence as a means to pressure the state for concessions in return for wartime sacrifices. Yet even here they were at a disadvantage compared to citizens. Colonial subjects felt the weight of the state's repressive apparatus to a much greater degree than did citizens. For example, in Southeast Asia, the colonial police occupied itself with extracting taxes from colonial subjects—often peasants engaged in subsistence agriculture—and putting down violent revolts.Footnote 28 As colonial economies moved toward wage labor and away from subsistence agriculture, the police became an instrument of not only internal order but also indigenous labor control to the benefit of settler capital.Footnote 29 For subjects, then, the threat of repression was omnipresent. This challenge was even greater for territories under direct military control, where few checks on the power of local military commanders existed. For example, in French West Africa, the vast territories that later became independent Mauritania, Niger, and Chad were under formal military administration, the effect of which was to dramatically increase the costs and risks of resistance to the state.Footnote 30

A further barrier was the repressive colonial apparatus's tremendous technological advantages over any would-be rebels or agitators. Besides superior military technology, these included advanced transportation, communication, and health infrastructure. This technology helped overcome three important obstacles to colonial expansion in much of the nineteenth century by (respectively) facilitating the movement of colonial troops, transmitting information in a timely manner, and blunting the impact of disease. The combination of a sophisticated coercive apparatus and advances in infrastructure made it much more difficult for subjects to credibly threaten violence as a means of extracting concessions.Footnote 31

Our claim is not that colonial states were totally unresponsive to the demands of subjects after wars of mass mobilization. Rather, we expect that colonial states were less likely to be responsive to subjects compared to citizens because subjects had fewer and weaker mechanisms for eliciting concessions from the state. Our theory predicts smaller expansion in the scope of public assistance—or, in cases of fiscal retrenchment, greater cuts in public assistance—in the places where the wartime burden fell more heavily on subjects than citizens.

More specifically, at the national level, our argument implies that the limited bargaining power of subjects meant metropolitan authorities were less likely to legislate increases in public assistance for colonial subjects compared to colonial citizens. Similarly, national authorities had little incentive to extend citizenship in exchange for military service, an alternative pathway to accessing public assistance benefits. At the subnational or local level, our argument implies that the localities that receive the smallest increases (or greatest decreases) in welfare spending are the localities with larger subject shares of the population and where subject casualty rates were higher.

Before proceeding, it is important to highlight three conditions that limit the scope of our theoretical claims. Because the expansion of the state into the domain of social and welfare service provision is a modern phenomenon, our theory does not apply to state formation in the premodern and early-modern periods. That period of state building largely concerns the centralization of authority in the sovereign and the creation of institutions for extracting wealth and labor. We also stress that our argument applies particularly to existential conflicts which necessitated military mobilization on a massive scale. When the burden of military service falls on a limited segment of the population, there are fewer individuals articulating demands on the state for wartime sacrifices,Footnote 32 and the state can meet those demands by providing private rewards rather than costly public goods.Footnote 33 This is particularly important in colonial contexts, where a combination of poverty, coercion, and inducements had long provided imperial armies with a steady supply of “volunteers.”Footnote 34

World War I in Colonial Algeria

We test our argument about the fundamental disadvantages confronting subjects in the context of the mobilization for World War I in Algeria. We select this case because it offers a number of theoretical and inferential advantages.

First, the mobilization of colonial troops by imperial powers during World War I was unprecedented.Footnote 35 Although there was significant variation in the degree to which various French colonies contributed to the war effort, Algeria's distinct administrative status, its proximity to France, and the extension of conscription to male Muslims in 1912 ensured that Algeria's subjects experienced mass mobilization in ways not dissimilar to French citizens in Algeria or the metropole.Footnote 36 For every Algeria-born French citizen who died in the war, almost two Algerian subjects gave their lives as well. This figure compares to approximately one citizen for every sixteen subjects in neighboring Tunisia and a staggering one citizen for every 100 subjects in French Sudan (now Mali), the second- and third-largest contributors of colonial troops in World War I after Algeria.Footnote 37

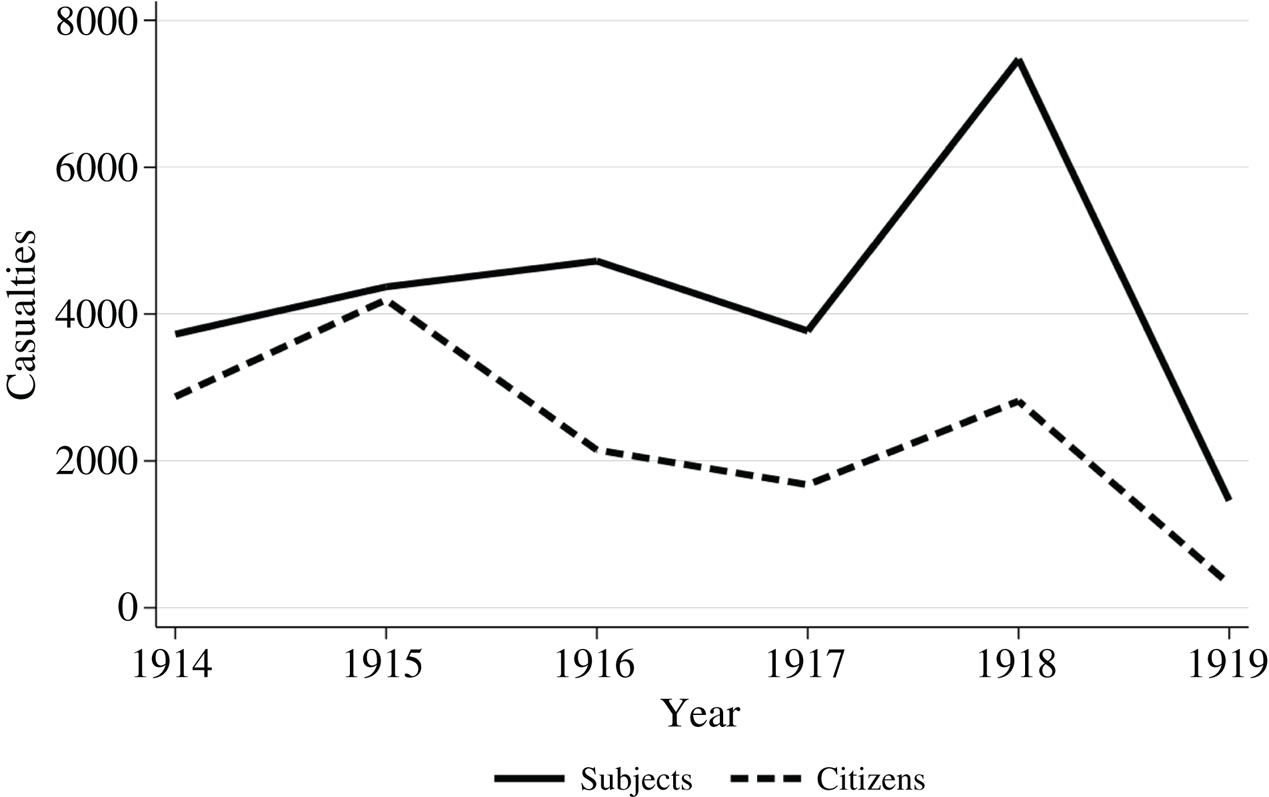

Second, the introduction of compulsory military service for Algeria's subjects made the burden of military service much more evenly distributed in Algeria than in any other part of the French Empire.Footnote 38 Figure 1 shows the losses that Algerian-born troops suffered immediately following mobilization: more than 6,000 died between August and December 1914 alone. By the end of the war, more than 40,000—about 1 percent of the total estimated population in 1911—would perish. Because citizens were a small share of the total population of Algeria, these casualties constituted a larger share of the community of French citizens in Algeria. By 1919, almost 2 percent of Algeria's French citizens had been killed in combat, compared to about 0.5 percent of all subjects. This shared war burden in Algeria allows us to isolate the subject disadvantage and the fundamental differences in bargaining power between citizens and subjects.

FIGURE 1. Algerian casualties in World War I

Third, because World War I was the first major conflict in which subjects were conscripted, it was not obvious ex ante how the French would respond after the war to the service of the thousands of subject conscripts. Although Algerians were intimately aware of the discrimination, prejudice, and racism of colonial governance, some elites believed that mass conscription would advance the political fortunes of Muslim Algerians and especially veterans,Footnote 39 a view shared by nationalist movements ranging from Ireland to India.Footnote 40

Fourth, colonial Algeria exhibits useful within-country variation in that citizen (settler) populations enjoyed an administrative status equal or comparable to those in the metropole, while the rights and privileges of colonial subjects were much more limited. In addition, fine-grained archival data on local spending are available for colonial Algeria before and after World War I. Exploiting this within-country variation offers greater inferential leverage than a national-level or cross-country design.

Mass Conscription, Citizenship, and Social Welfare

We are not the first scholars to study the fundamental disparities and inequalities of French colonial rule in Algeria, a topic that generations of historians have examined.Footnote 41 Here we review evidence from this vast literature as well as primary source data on elite political debates. Together, the evidence provides prima facie support for our theoretical claim that the reduced bargaining power of Algerian subjects meant that French government had little incentive to extend social welfare benefits to them after mobilization.

In 1907, the French government began to formally investigate the feasibility of conscripting colonial subjects to reduce growing disparities in manpower with Germany.Footnote 42 This proposal signaled a major policy shift. Although Algerian units had served with distinction in all of France's major conflicts throughout the nineteenth century, compulsory military service was a duty traditionally reserved for citizens since the declaration of the French Republic. As one recent study notes, “not only was conscription an embedded practice in French society but it also carried with it a sense that political rights were the direct corollary of military service.”Footnote 43 This meant that the proposal to extend conscription to Muslim subjects was extremely controversial, particularly for the settler community in Algeria, which vociferously opposed any change in policy. A typical op-ed from 1910 argued that the extension of compulsory military service would “compromis[e] the security of African France by arming a race which was only yesterday our enemy and resentful of our control. What will happen to the predominance of the French community if to this blood tax [conscription] you add its corollary, the right to vote?”Footnote 44

Many Muslim elites also opposed the expansion of military conscription. However, in urban centers throughout the colony a small group known as the Young Algerians engaged in a sustained press campaign arguing that conscription represented a political opportunity for Algeria's subjects.Footnote 45 Despite the strenuous objections of many prominent colons and the ambivalence or opposition of the most prominent Muslim elites, the existential threat that Germany posed led to the introduction in 1912 of compulsory military service for all male Algerian subjects of eligible age.Footnote 46

Political elites from the settler community may have failed to scuttle the expansion of conscription to subjects, but they were successful in heading off any formal recognition of greater political rights. While the decree that expanded conscription guaranteed colonial subjects the same pay and benefits as colonial citizens, it provided no special pathway to citizenship for military veterans.Footnote 47 Furthermore, the conscription law included provisions for a special payment for subjects that was not made to citizens, which put Muslim conscripts in a category “between hired mercenaries and full French citizens.”Footnote 48

In 1912, in response to this unfavorable outcome, a delegation of the Young Algerians met in Paris with a range of political elites, including the French president, and argued for equality in the terms and conditions of conscripts without respect to civil status. Their supporters simultaneously coordinated a petition campaign from hundreds of Algerian fathers stating that unless they were given the rights of citizenship, they would refuse to send their sons to fight in the French army.Footnote 49

These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful. Rather than providing a pathway to citizenship for veterans, the major 1919 postwar reform known colloquially as the loi Jonnart (Jonnart's law) extended the franchise to indigenous males who had completed their military service, but kept in place a number of onerous conditions that dissuaded many veterans from voting. These restrictions meant that the loi Jonnart did nothing to change the colonial institutions that systematically favored the interests of the European minority, ensuring that Algerian subjects confronted prejudice and discrimination on a daily basis.Footnote 50

Given the fundamental political disparities between citizens and subjects before World War I, it is reasonable to ask whether Algeria's subjects should have expected anything to change after armistice. Secondary sources suggest that the tradition of restricting conscription to French citizens prior to World War I, the centrality of the “blood tax” in Republican ideology, the existential nature of the German threat, and the fact that Algeria was administratively part of France all militated in favor of greater rights for Algerian subjects—including veterans—up to and including citizenship. With the benefit of hindsight this claim may seem improbable today. However, prior to World War I the Algerian nationalist movement was in its infancy, and the most influential political activists among Algerian subjects largely favored advocating for greater rights, not outright independence.Footnote 51

The experience of the so-called Four Communes of Senegal illustrates what might have been in Algeria. Like Algeria, these four cities enjoyed a special administrative status, including a representative in the National Assembly after 1879. The plight of the originaires, the name given to Africans born in the Four Communes, provides a useful counterfactual to subjects in Algeria. In 1916, Blaise Diagne, the first West African member of the Chamber of Deputies, was able to finally secure full citizenship rights for the originaires; his appeal for these rights was based in part on the military service of the originaires to France. Before the end of World War I, Diagne was also able to obtain the concession that at least some military veterans from West Africa would be eligible for French citizenship, greatly facilitating a major recruitment drive across Guinea and Mali in 1918.Footnote 52

Evidence from secondary sources suggests that Algerians could hardly be blamed for anticipating that wartime sacrifices might lead to greater political rights, especially for veterans and their families. But what did political elites themselves say about conscription in the lead-up to World War I and about public assistance immediately following the conflict?

To answer these questions, we examine a collection of transcripts from the annual meeting of the délégations financières to illustrate the aspirations and goals of political elites in Algeria before and after World War I. Like so many institutions, these delegations reflected the profound political inequalities of colonial Algeria. Created in 1898 as means of devolving some authority from the colonial administration, three separate delegations composed of representatives from the French, European, and subject communities met annually with representatives from the colonial administration, as well as Algeria's representatives in the National Assembly, to discuss and vote on the colonial budget. Forty-eight delegates represented the French and European communities, and twenty-one represented the subject population. While all the European representatives were directly elected, only fifteen of the representatives for Algerian subjects were; the colonial government directly selected the other six. The power of these delegations was highly circumscribed, and their “vote” largely symbolic. Still, these transcripts provide a window into elite debates on spending and public assistance before and after World War I.Footnote 53

The meeting of non-colon deputies on 13 May 1913 provides a vivid illustration of the consternation that extension of universal male conscription to Muslim subjects inspired within the pied noir community. Deputy Émile Morinaud noted that if conscription were imposed, “the indigenous will demand the right to vote just like French citizens! That day we will be submerged by the indigenous masses.”Footnote 54 In the same session, deputy Émile Picot elaborated on the same sentiment, albeit in more explicitly ethnic and materialist terms: “A simple decree is not enough to make someone French … They are Muslims before all else, and so they will remain … I am in favor of using the indigenous element if it is in defense of the Fatherland, but volunteers will present themselves in more than sufficient numbers if we offer them more advantageous circumstances than those currently in place with respect to salaries and pensions.”Footnote 55 While other perspectives were shared during the long debate, most deputies either implicitly or explicitly recognized the concept of the “blood tax” linking conscription with the right to vote.Footnote 56

Later that summer, in the meeting of the indigenous deputies, deputy Mohamed Bel Hadj Ben Gana addressed the controversial extension of conscription in terms clearly designed to address the fears raised by the representatives of Algeria's European community: “We call for the suppression of the 250-franc bonus, which we consider humiliating, because it would make our sons mercenaries and not conscripts. If France needs the blood of our sons, we are prepared to give it, but out of love and not venality … As for the benefits that have been demanded by our people, it seems obvious that France, whose love and fair benevolence for its Muslim subjects we all know, will recognize their loyalty and will accord them the satisfaction they merit.”Footnote 57

In the same session, the deputies directly attacked the Young Algerian delegation that had traveled to Paris to argue for the extension of citizenship to Algerians. In a statement that was unanimously adopted, the deputies stated that “the hour has not come when our coreligionists will demand to be French citizens. They remain faithful and loyal subjects of their adopted country, ready to consecrate their blood, proud to contribute to France's might and grandeur.”Footnote 58

These transcripts illustrate the significance of the extension of conscription to Algerian subjects. Even before the outbreak of World War I, French and indigenous political elites recognized the special symbolism of the extension of conscription to Muslim subjects and strongly associated it with the opportunity to press for greater political rights, especially for veterans.Footnote 59

Because the délégations financières were focused on the national budget, they do not provide direct insights on debates between local political elites at the commune, where key decisions on funding for social welfare were made each year. To address this gap, we combine qualitative evidence from one of the few sessions that provide direct insights on local social welfare spending during World War I with official statistics on the bureaux de bienfaisance. These local offices, funded through a combination of donations from local elites, taxes, and support from the national government, provided financial and material assistance to the most destitute and marginalized, with separate offices serving the European and indigenous communities. Not surprisingly, because these facilities were located in major urban areas, poor Europeans enjoyed much better access to this assistance than subjects, the overwhelming majority of whom lived in rural areas. In 1914, for example, across all three départements, 472,721 Europeans (about 63 percent) lived in a commune with a bureau de bienfaisance, as compared to 344,729 indigenous (about 11 percent).Footnote 60

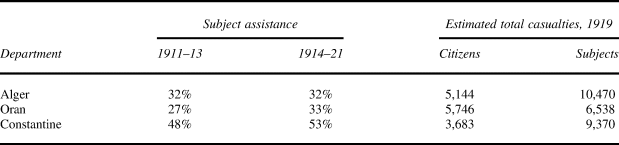

Table 1 provides subnational evidence of the consequences of the failure to secure citizenship rights for veterans and their families. The table reports the percentage of charitable spending on Algerian subjects, by département, before and after World War I. Although subjects comprised the vast majority (nearly 90 percent) of the population in all three départements, only in Constantine did Muslims receive the majority of assistance.Footnote 61 Moreover, despite increasing need as a direct result of the massive loss of working-age men after 1914, local charitable assistance remained flat in Alger, the most populous département. In Oran and Constantine there was a slight increase in public assistance to subjects after the war. Nor were these disparities limited to public assistance. Archival evidence suggests that even shortly after armistice, Muslim veterans and their families confronted a wide range of obstacles—political, bureaucratic, and practical—to accessing funds that European veterans did not.Footnote 62

TABLE 1. Local charitable spending, before and after mobilization

Note: Table depicts the percentage of charitable spending on subjects by the bureaux de bienfaisance and total casualties by department.

Qualitative evidence from the délégations financières sheds light on two mechanisms by which these inequalities were perpetuated before and after the war. First, because municipalities had to approve the placement of a bureau de bienfaisance, it was possible for local authorities to veto the expansion of these facilities. This appears to have been the case in the city of Tizi-Ouzou. Despite repeated appeals by deputies to the colonial authorities from 1906 to 1920, municipal authorities opposed expansion, and approval was never extended.Footnote 63 This meant that as late as 1921 the largest city in the Kabylie region had no bureau de bienfaisance despite a Muslim population of over 29,000 in 1911 and 243 war casualties by 1919.Footnote 64

A second mechanism was associated with funding for the bureaux de bienfaisance. Money raised through local taxes was the primary source of funding for these public charity offices. During periods of financial duress, such as World War I, need could quickly exceed the available local funds, even where a bureau was present. While deputies could and did appeal to the colonial administration for more assistance during fiscal emergencies, there was no guarantee that such demands would be met. In a speech in the 1917 session, a representative from the Algerian government explained that in Blida, a small city forty-five kilometers outside Algiers,

the mothers, wives, and infants of those indigenes who left to defend the French frontier were the charge of the commune. Our plan was all mapped out: open the doors of the bureau de bienfaisance and register all of the families whose breadwinner had left to join the army. In Blida we registered a few more than 100 in just a few weeks. However, despite the best wishes of the government and the prefecture, our resources were not augmented by a cent … During the year of 1916, to the great scandal of the indigenous and European communities, I had to close the bureau. I had to tell the families of those indigenous soldiers, who were defending France, that I had nothing more to give them. Circumstances forced me to make this declaration, but it broke my heart.Footnote 65

This qualitative evidence points to significant disparities between citizens and subjects in rewards for service despite similar sacrifices on the battlefield. But do these anecdotal accounts generalize? And how much of a penalty did colonial subjects pay relative to colonial citizens in the aftermath of the war? To answer these questions, we now turn to a statistical assessment of the relationship between citizens, subjects, and social welfare spending at the subnational level during World War I.

Estimating the Subject Penalty

Our goal is to assess the effect of the subject disadvantage on public spending in the aftermath of World War I. We formally test our argument using official data drawn from the three départements of Algiers, Oran, and Constantine and the vast southern territories administered by the French military. To our knowledge, we are the first to digitize and analyze these historical data at the commune level. Our selection of the commune as the unit of analysis reflects its important role in local administration and delivery of social services.

We construct a commune-year panel data set covering 361 communes between 1911 and 1921: from three years prior to the outbreak of World War I to three years after the armistice. We select these years because 1911 is the first year for which data are available on the formal expansion of local spending on public assistance; the last enumeration of the population prior to World War I was also in 1911.

Dependent Variable: Social Assistance and Pensions

Our outcome of interest is social welfare spending. We focus in particular on two types of welfare: pensions (for local government employees) and public assistance (medical care and assistance for the socially vulnerable). Data on spending come from local commune reports, in a series called Statistique financière de l'Algérie. These reports represent the most detailed and authoritative accounts of local fiscal data available.Footnote 66

We focus on these two categories because they are directly tied to wartime service but represent distinct aspects of social welfare. Pension benefits, which were first introduced for state employees in the metropole in the early 1800s,Footnote 67 were limited almost exclusively to local government employees in Algeria. In practice this meant that the overwhelming majority of recipients would have been French citizens, since few Algerian subjects were employed by local municipalities during this period. Moreover, because government services were overwhelmingly concentrated in a few major urban agglomerations, pensions constituted far less than 1 percent of the commune budgets, on average. For these reasons we view pensions as a very difficult test for our theory.

Social assistance spending was more broad-based. Separate medical facilities administered care to citizens and subjects, and distinct local charity offices provided assistance to the most vulnerable and needy members of both communities. Although the largest of these facilities were located in major urban centers, almost all communes set aside a significant portion of local tax revenues for public assistance. This category of welfare targeted the most vulnerable members of society, and averaged around 10 percent of the local budget, a slightly larger share on average than what communes dedicated to local policing.

One challenge with simply using the totals included in the fiscal reports as our dependent variable is that the reports do not provide any insights about the identity of recipients of this spending at the local level. To the best of our knowledge, comprehensive data on beneficiaries do not exist in any systematic format. Although population data could be used to construct an alternative per capita measure of spending, we view this approach as “baking in” assumptions about how this money was allocated—assumptions that are inconsistent with the descriptive evidence that suggests that spending disproportionately benefited colonial citizens over subjects.

To account for disparities in spending driven by differences in population, as well as to facilitate interpretation, we standardize the yearly reported pension and welfare totals by dividing them by the total annual expenditures for each commune. We view this measurement strategy as capturing the degree to which local officials prioritized spending on pensions and public assistance in a given year.

Independent Variable: Subject Share of Population

To measure the differential effect of wartime service and sacrifice, we would ideally know exactly how many individuals were mobilized in each commune, as well as their status as citizens or subjects. To the best of our knowledge, these data do not exist. Instead, we rely on data from the Tableau général des communes de plein exercice, mixtes et indigènes des trois provinces. These tabulations provide the most systematic and disaggregated data on the population publicly available.Footnote 68 We use the categories in this series to code the subject share of the total population.Footnote 69 In the specifications that follow, we rely primarily on the 1911 dénombrement, the last taken before 1914.Footnote 70

This measure serves as a suitable proxy for wartime service for two reasons. First, under universal male conscription, the composition of the local population heavily influenced conscription. Second, the law introducing conscription for Algerian subjects explicitly required local administrators to enumerate the local population to identify all eligible military-age men. This process invariably relied on the dénombrement, which was the most comprehensive official tabulation of the population in existence at the time.

Estimation Strategy

One challenge we face is that historical evidence suggests that the simple association between subject share of the commune population and spending share for our outcomes would be biased.Footnote 71 As with most colonies, settlement patterns in Algeria were not random. If the factors that influenced where French citizens chose to settle (which in turn affects the subject share of the population) also influenced spending decisions, excluding those confounders would lead to omitted variable bias. The historical literature on colonial settlement patterns suggests that the most likely confounders are geographic. French settlers tended to live in areas that were easier to access and more suitable for agriculture;Footnote 72 these physically accessible areas were also more likely to have higher levels of state presence, an important factor for the distribution of public goods and social services.Footnote 73

We address this empirical challenge by estimating the effect of the subject disadvantage using a difference-in-differences research design. A typical difference-in-differences design uses a shock, often the introduction of a new policy, to compare differences between “treated” units exposed to the shock and “control” units not exposed to the shock in an outcome of interest before and after implementation.Footnote 74 The introduction of compulsory military service in 1912 ensured that war mobilization impacted all of Algeria's communes, meaning that all localities were “treated” by the impact of conscription. However, this is not to suggest that all communes were equally impacted by mobilization.

We employ a variation of the standard difference-in-differences design that exploits variation in exposure to a policy, rather than a strict distinction between treated and control units.Footnote 75 Our theory suggests that variation in the composition of the local population moderates the relationship between mobilization and social welfare. In communes where subjects represented a larger share of the population, a larger portion of conscripts were subjects. Our theory suggests that in such places, postmobilization spending was much less likely to increase than in communes where the subject share of the population was small. In other words, in high subject-share areas, most of the mobilization burden fell on colonial subjects, and the colonial state had a greater incentive to shirk its postwar commitments to the expansion of public assistance. This suggests the following specification:

where Y is our outcome of interest (pension or public assistance spending as a share of total expenditures) in commune j for a given year k, α j is the commune fixed effect, β k is a year fixed effect, P j denotes the share of subjects as enumerated at the commune level in 1911, T k indicates whether the commune was observed before or after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, C j is a vector of commune-specific controls, including interactions of all control variables with the subject share and the treatment dummy, and ![]() $\epsilon _{jk}$ is an error term. All specifications include clustered robust standard errors at the level of the commune.

$\epsilon _{jk}$ is an error term. All specifications include clustered robust standard errors at the level of the commune.

We account for potential geographic confounders by coding a number of additional variables that appear in vector C j. We use geospatial data to calculate each commune's mean elevation and distance from the coast, and we use historical estimates of population and land use in 1820 from the HYDE database to estimate the mean precolonial population and cropland density.Footnote 76 We also code five measures related to state and settler presence using data from the Tableau général. These include a binary indicator of whether the commune had a railroad station in 1901 (when the railroad network was largely completed); the area of the commune, since larger communes tended to have fewer French settlers; the year when the commune was legally established, to account for disparities driven by variation in the expansion of the colonial state; and whether the commune was the capital of its respective arrondissement (second-level division) or département. All these confounders capture characteristics that predate 1911, the first year we observe in our panel, to avoid inducing post-treatment bias in our estimates. The only exception is commune area, which changes slightly as the territorial extent of each commune changes.

The key assumption of the difference-in-differences research design is that of “parallel trends”: while there can be differences in levels between treated and untreated units, trends in the outcomes of interest should be comparable prior to the shock and diverge only afterwards. Two key data constraints inform how we defend this untestable assumption.

A first challenge is that the continuous nature of our main explanatory variable, the subject share as enumerated in 1911, makes it difficult to visually test this assumption. Although there were some communes with few subjects and many communes with very few citizens, we cannot simply split our sample between treated and untreated units because conscription was mandatory for all adult males regardless of citizen/subject status. A second challenge is that public assistance dramatically expanded in 1911, raising questions about the comparability of observations from earlier periods for this outcome.

To defend the parallel trends assumption, we examine the balance in our variables prior to 1914. We run simple regressions to assess the association between the subjects share as enumerated at the commune level in 1911 and our main controls (almost all of which are time invariant) as well as our main outcome variables of interest: spending on pensions and public assistance as a share of total expenditures. A greater share of colonial subjects is associated with higher elevation, greater distance from the coast, lower precolonial population and crop density, larger administrative area, and lower likelihood that a commune would have a railroad station or be designated as an administrative capital.Footnote 77

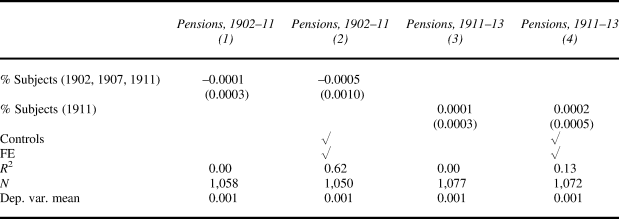

What about disparities in the share of subjects and spending on pensions or public assistance prior to 1914? Table 2 shows the association of our main outcomes prior to mobilization for World War I and the subject share of the population. Because we observe the subject share of the population in only 1902, 1907, and 1911, we use two different approaches in testing for pre-trends. First, we construct a panel using only these three years. Second, we separately examine the three-year period prior to the outbreak of World War I; we observe population data in 1911 but lack population data in 1912 and 1913. In both cases, we find no association between the share of subjects and the share of the budget devoted to pensions, with or without the inclusion of fixed effects.

TABLE 2. Association of subject share and pension spending

Notes: Commune and year FE, column 2; arrondissement and year FE, column 4. Clustered robust standard errors at commune. *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

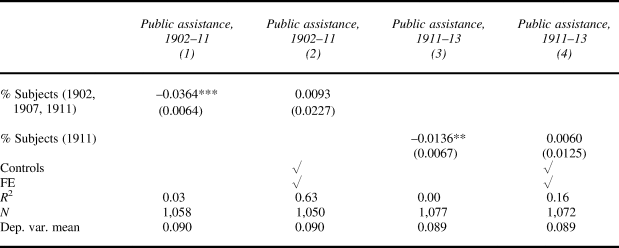

Table 3 repeats the same approach for the public-assistance outcome. An increase in the subject share is associated with lower rates of public assistance spending if we do not include controls (columns 1 and 3). This association is significant for both the 1902–11 (column 1) and 1911–13 (column 3) subsets, but is no longer significant once we include year and administrative fixed effects (columns 2 and 4).Footnote 78 These results increase our confidence that prior to the war the local subject share of the population was not associated with higher or lower rates of spending in terms of pensions or public assistance, despite the association between subject share and the geographic and administrative confounders.Footnote 79

TABLE 3. Association of subject share and public assistance spending

Notes: Commune and year FE, column 2; arrondissement and year FE, column 4. Clustered robust standard errors at commune. *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Results

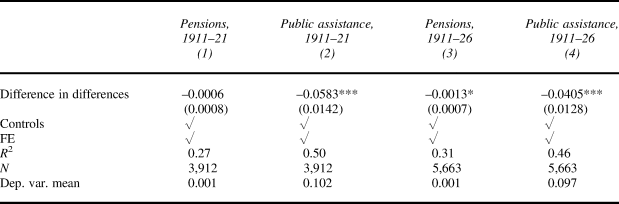

How much of an impact did a greater share of colonial subjects have on spending levels after the outbreak of World War I? Table 4 shows the results of our difference-in-differences specification for our two outcomes of interest.Footnote 80 While there is a negative association between the share of subjects and pension spending, it is not statistically significant (column 1). This is because relatively few communes paid pensions at this time, most of the beneficiaries of these pensions were French citizens, and communes exercised less discretion over these payments. A 1 percent increase in the subject population decreased spending on public assistance by 5.8 percent, a large and substantive effect (column 2).

TABLE 4. Effect of subject penalty on welfare spending

Notes: Commune and year FE, column 2; arrondissement and year FE, column 4. Clustered robust standard errors at commune. *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Our main specification focuses on a narrow window of time: 1911 to 1921 (from three years before hostilities to three years after). This narrow bandwidth affords us greater confidence that the differential effects in welfare spending stem from mobilization. Given the fiscal pressures the French state confronted during the war, we next investigate whether the effect of the subject penalty was temporary or endured after armistice. To do so, we extend our bandwidth to 1926, the last year prior to the enactment of legislation that reformed pension schemes. Columns 3 and 4 show that the wartime-induced disparities persisted twelve years after mobilization. We can see that the estimated effect of the subject penalty is larger for pension spending (about 0.1 percent) and weakly significant, and slightly attenuated (but still negative and strongly significant) for public assistance spending relative to the results presented in Table 4. We interpret these results as consistent with the idea that the subject disadvantage continued to influence local spending more than a decade after the initial mobilization for World War I.

Table 4 provides evidence consistent with our claim that localities with a greater share of colonial subjects were less likely to benefit from the postmobilization expansion of social welfare. Even after accounting for local disparities in physical accessibility (average elevation and distance from the coast), precolonial conditions that would have driven settlement patterns (estimated population density and agricultural cultivation), as well as state presence (the area of the commune, the date it was established, and whether it was part of the railroad system or if it was an administrative capital), communes with a greater share of colonial subjects received significantly less funding for social assistance in the immediate aftermath of the war, and these disparities persisted more than seven years after 1918. These disparities emerged more slowly for pension spending. There were no disparities in pensions in communes with a greater share of subjects until more than ten years after mobilization.

Assessing the Mechanisms: Casualties and Postwar Spending

Thus far we have shown that, in line with our theoretical expectations, welfare spending was lower in communes with larger subject shares of population following mobilization in 1914. Now, we explore the mechanisms underlying this finding. Specifically, we examine other spending outcomes to explore how spending shares changed after mobilization. The expanded set of outcomes allows us to better understand the budgetary priorities of local administrators. We also examine whether year-to-year variation in casualties compounded the political disparities confronting subjects after 1914.

Our expanded set of outcomes includes four additional spending categories. These are education, the share of the local budget devoted to schooling; sanitation, the share spent on sewers and drains; police, the share spent on the police force; and roads, the share spent on public roadworks.

To examine whether casualties compounded the subject penalty, we code a variable that measures the cumulative share of subject casualties by commune from 1914 until 1919. These data come from a new data set compiled by the French Ministry of Defense. Though it is not comprehensive, it is the largest publicly available data set that records the place of birth of French combatants who died in World War I; it thus offers the best data on Algerian-born military casualties.

We assume that death in war is essentially random; if so, casualties offer a representative measure of local recruitment. This is not to suggest that recruitment itself was random, an assumption that is not necessary to draw valid inferences about the mechanism. Patterns of local recruitment reflected varying conditions in the strength of the colonial state and local “push” factors, like poverty, which historical accounts emphasize was crucial in driving young men into the arms of the colonial military.Footnote 81

Determining whether an individual born in colonial Algeria was a French citizen or an Algerian subject is difficult because the database does not provide this information explicitly. We address this challenge by exploiting differences in names between French colonial citizens and subjects. Throughout the colonial period, Algerian Muslims remained fiercely protective of their own culture and traditions, which included naming conventions for their children. As a result, French citizens and subjects had distinct first names. We assume that individuals with typically “European” first names were unlikely to be Muslim subjects.

We examine every first name in the Ministry of Defense data set. We identify approximately 1,000 distinctly European first names such as Aaron, Étienne, and Jean, and code these individuals as French citizens. We include Jewish first names in this list because the Crémieux decree of 1870 granted citizenship to Algerian Jews. We code all other individuals as Algerian subjects. Of the 36,859 individuals in the data set for whom we are able to identify a place of birth, 13,819 (37 percent) are identified as “citizens” using this approach.

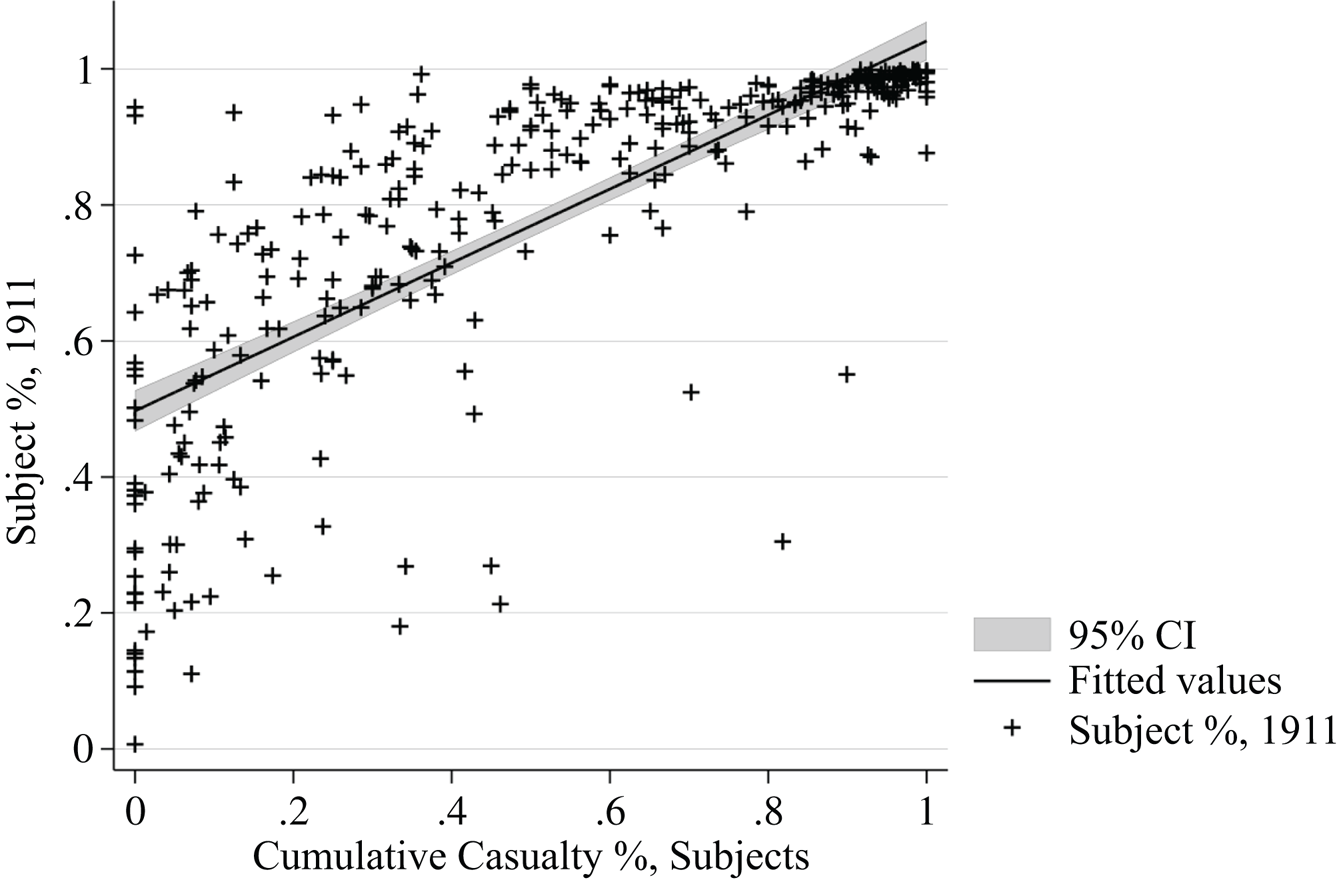

Figure 2 illustrates the positive association between the cumulative share of subject casualties in 1919 and the local share of subjects in 1911. Because this association is strong but not perfect (ρ = 0.77), we include the 1911 subject share of population in the regression to “net out” the effect of the subject penalty following mobilization.

FIGURE 2. Association of subject share in 1911 and cumulative casualties in 1919

We estimate specifications that use a two-way fixed effects model, employing fixed effects for the arrondissement, the administrative level above the commune from which we take our total counts, and each year reported in the Ministry of Defense data set—1914, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1918, and 1919—to account for variation in casualties over time. We use this higher-level (admin-2) fixed effect because the Ministry of Defense's crowd-sourced transcription of the handwritten places of birth and the process of transcribing these locations was inherently less precise than the official enumerations used to establish the share of local subjects and citizens in the dénombrement. This higher-administration fixed effect is also necessary in order to include the 1911 subject share of population variable, which in turn allows us to differentiate between the effects of political disadvantage after mobilization and variation in casualties during war.Footnote 82

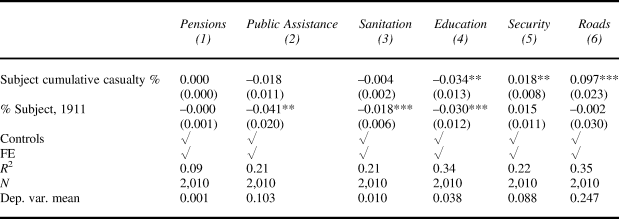

Table 5 reports the association between our standardized measures of social welfare and yearly variation in the share of local subject casualties for the war years. We see no association between either measure and the share of pension spending, probably because relatively few local communes provided pensions for their employees, and those that did focused their efforts on colonial citizens. For public assistance, we see that the local share of the population is driving the relationship. Although the casualty share measure is signed in the theorized direction, it is not statistically significant. This result indicates that spending on public assistance was lower in communes with a large number of subjects following mobilization, irrespective of the actual share of subject casualties during the war years.

TABLE 5. Association of citizen casualties and wartime public spending,1914–19

Notes: Commune and year FE, column 2; arrondissement and year FE, column 4. Clustered robust standard errors at commune. *p < .10; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Because our outcomes are measured as shares, columns 3 to 6 examine whether local communes were simply prioritizing other areas of expenditure during the war years. Column 3 suggests that communes with a greater share of subjects faced a similar political disadvantage when it came to spending on sanitation. Column 4 suggests that disadvantage also existed for education spending, and this disparity was compounded as the share of subject casualties increased over time. Columns 5 and 6 provide some sense of the areas of the budget that local authorities prioritized instead. As the share of subject casualties increased, so did spending on the police and road construction.

Taken together, these results suggest that following mobilization, communes with a greater share of subjects faced political disadvantages with respect to local spending on public assistance, sanitation, and education. Greater subject casualties actually further decreased the share of the budget local communes devoted to education. During the war years, as subject casualties increased, rather than prioritizing public assistance, local governments prioritized the police and road construction. This result is consistent with the idea that local communes were increasingly concerned about security and public order in the face of mounting subject casualties.

Scope Conditions and Generalizability

We have argued that subject populations are politically disadvantaged when bargaining with the state for rewards in return for wartime sacrifices, and that this disadvantage drives differential expansion in social welfare spending. Although we draw evidence from colonial Algeria, our theoretical insights about the subject penalty are not limited to the former French Empire. We expect our argument to generalize under three conditions.

First, our theory should apply to conflicts involving large numbers of soldiers. Our subject penalty concept is predicated on the idea that the state is unable or unwilling to provide rewards for service on a private basis. When states fight wars using a relatively small number of highly skilled specialists, it is more efficient to deliver rewards in a targeted, individualized manner rather than in the form of broad-based social services. For this reason, we do not expect our theory to apply to historical periods before the introduction of large standing armies.

Second, our theory should apply when both marginalized and nonmarginalized groups serve in the military. The subject penalty is about the differential ability of a marginalized group to pressure the state for concessions in return for wartime sacrifice. For such a disadvantage to exist, there must be salient political divisions among soldiers.

Third, our theory is most applicable when states use conscription as a method of military recruitment. In the face of the state's demand for their labor, individuals could comply or resist. Broad-based rewards—always delivered in the shadow of coercion—shape citizen calculations about compliance. All-volunteer armies sidestep this problem because recruits opt in to military service. This distinction is especially important in the context of World War I because many of the imperial units, particularly in the British military, were technically composed of “volunteers.”Footnote 83

Examples within and outside the French Empire suggest that our theory applies to cases that meet these conditions. In 1959, faced with the independence of virtually all of France's remaining colonial possessions in Africa except for Algeria, French president Charles de Gaulle announced that the pensions of veterans in former French colonies would be fixed at rates lower than those of their comrades in arms in the metropole. This represented a fundamental rupture with the principle that all French soldiers should be equally compensated for their service, an ideal enshrined in the 1912 mass conscription laws that explicitly established parity in compensation and pensions between citizens and subjects in Algeria and French West Africa.Footnote 84 This decision had immediate impact on the pensions of thousands of veterans. As one previous study notes, African veterans were paid “3 to 30 percent of the rates which their metropolitan peers were paid.”Footnote 85 This decision remained unchallenged until a ground-breaking legal case in 2001 determined that a Senegalese veteran of World War II was owed arrears after decades of underpayment on his military pension.Footnote 86

Or consider the plight of veterans from the Philippines, which became a US colony in 1898. An estimated 250,000 Filipinos fought for the US military in World War II.Footnote 87 In 1946, the year in which the Philippines achieved its independence, Congress passed the Rescission Act, which effectively excluded Filipino veterans from the G.I. Bill and other veterans benefits, despite President Roosevelt's promises to the contrary. President Truman noted in an official statement, released when he signed the Rescission Act into law, that

Philippine Army veterans are nationals of the United States and will continue in that status until July 4, 1946. They fought, as American nationals, under the American flag, and under the direction of our military leaders. They fought with gallantry and courage under most difficult conditions during the recent conflict. Their officers were commissioned by us. Their official organization, the Army of the Philippine Commonwealth, was taken into the Armed Forces of the United States by executive order of the President of the United States on July 26, 1941. That order has never been revoked or amended. I consider it a moral obligation of the United States to look after the welfare of Philippine Army veterans.Footnote 88

Seventy years after Truman's statement, few Filipino veterans or their descendants view the United States as having met its legal or moral obligation. In 2009, Congress authorized a one-time lump sum payment, with disparate funding levels for citizen and noncitizen Filipino veterans.Footnote 89 Yet this belated payment pales in comparison to the benefits, like the G.I. Bill, that other World War II veterans and their descendants enjoyed.

Our theory contributes to understanding disparities in social welfare expansion in other cases as well. Like France, the British Empire relied heavily on subject populations in both world wars. For example, in World War I alone the British mobilized more than 1.5 million Indian subjects. Although historians have begun to investigate this massive mobilization of colonial troops,Footnote 90 to the best of our knowledge the effects of this deployment on the unequal expansion of the state in India remain underexplored. Nor are these insights strictly limited to former colonies. American scholars have long noted the pernicious effects of racial discrimination for the expansion of social welfare and veterans benefits among African Americans, particularly those residing in the South.Footnote 91

Conclusion

Theories of state building often focus on macro-historical factors that shape the exercise and scope of state power. That power does not touch the lives of the governed equally. Who the state chooses to reach and who it chooses to neglect in pivotal moments of state building can have serious repercussions for welfare and well-being for generations. The disparities in social spending that we study in this paper reveal the highly unequal ways in which wars of mass mobilization shaped the expansion of public goods and assistance. These disparities are only detectable when moving from aggregate measures to variables that take into consideration politically salient differences that historians of the developing world have long highlighted. These differences fundamentally shaped the expansion of the state, especially in former colonies.

Grappling with the disparities in the way states respond to the wartime sacrifices of their subject populations is both a scholarly and a moral imperative. From a theoretical standpoint, the inability of certain populations to extract concessions from the state has implications for the generalizability of bellicist theory beyond early modern Europe. Much of bellicist theory focuses on the initial construction of state institutions. Our paper advances this literature by showing that wartime pressures can also explain the expansion of state scope, or what Ansell and Lindvall call the “revolution in government.”Footnote 92 It also suggests an intriguing explanation for why wars built states in some parts of the world but not others. If state expansion is predicated on both the state's demand for extraction and the public's ability to make claims on the state after military service, then scholars must be attentive to the conditions under which the public can enforce those claims. Those conditions are much less likely to hold in nonsovereign polities, and among subject populations specifically.

The subject penalty also suggests that bargaining power is an important factor that conditions standard narratives about the relationship between warfare and welfare. As scholars of the welfare state have recognized, who has access to political power determines variation in welfare state expansion.Footnote 93 Our paper demonstrates the importance of differential bargaining power on the basis of citizen/subject status. Theories developed on the experience of nonmarginalized social groups cannot be grafted onto the experience of the marginalized without attending to the fundamental differences in power and status that constrain disadvantaged groups.

From a moral standpoint, recognizing these disparities goes beyond correcting an omission in official histories or improving the rigor of social scientific theories. Many of the subjects who fought for colonial powers like France, Britain, and the United States served honorably only to realize that their sacrifices were less valued than those of their fellow soldiers who happened to be citizens. Veterans and their families have never forgotten those sacrifices. To avoid obscuring these legacies, studies of state building and state development should employ measures that explicitly account for the fundamental disparities between citizens and subjects.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818322000376>.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Nicholas Reynolds for assistance with acquiring some of the primary source materials used in this study. We thank Amber Afzali, Mathew Chemplayil, Damon Duchenne, Brandon Gauthier, Montagu James, Jeongmin Park, Amani Selmi, Rita Slaoui, and Conor Vance for research assistance. We thank Scott Abramson, Mark Blyth, Jeremy Bowles, Marc Grinberg, Steve Levitsky, Rick McAlexander, Carl Muller-Crepon, Joan Ricart-Huguet, Mark Schwartz, Hillel Soifer, and Madeline Woker for their comments.