In 2008 a global economic crisis affected Europe as well as the rest of the world. The crisis caused problems in the banking sector and downturns in stock markets, bankruptcies, house repossessions and there were rises in unemployment. 1 There was concern expressed about the effect of austerity on healthcare Reference Reeves, McKee, Basu and Stuckler2-Reference Katikireddi, Niedzwiedz and Popham15 and the World Health Organization (WHO) published its concerns regarding the impact of the crisis on global health, although at least some points were proven exaggerated and unsupported by data and withdrawn later. 16-Reference Fountoulakis, Savopoulos, Siamouli, Zaggelidou, Mageiria and Iacovides20 Mental health is believed to be at a greater risk of being affected by such a crisis, since people with mental disorders (particularly mood disorders) constitute a particularly vulnerable population. Among all adverse effects, the most striking would be an effect on suicidality. It is widely believed that crises of this kind increase suicides, Reference Kentikelenis, Karanikolos, Papanicolas, Basu, McKee and Stuckler10,16,Reference Swinscow21-Reference Luo, Florence, Quispe-Agnoli, Ouyang and Crosby25 and this seems to be the conclusion of studies on the Asian economic crisis of the 1990s, with a particular emphasis on the effect of rising unemployment. Reference Chang, Gunnell, Sterne, Lu and Cheng26,Reference Chang, Sterne, Huang, Chuang and Gunnell27 Thus, it is supposed that the greatest impact is on men of working age. There are several studies suggesting a similar pattern concerning the impact of the recent economic crisis in European countries Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee8,Reference Kentikelenis, Karanikolos, Papanicolas, Basu, McKee and Stuckler10,28-Reference Economou, Madianos, Peppou, Theleritis, Patelakis and Stefanis37 and the USA Reference Reeves, Stuckler, McKee, Gunnell, Chang and Basu34 although different interpretations also exist. Reference Fountoulakis, Grammatikopoulos, Koupidis, Siamouli and Theodorakis19,Reference Fountoulakis, Savopoulos, Siamouli, Zaggelidou, Mageiria and Iacovides20,Reference Fountoulakis, Siamouli, Grammatikopoulos, Koupidis, Siapera and Theodorakis38,Reference Fountoulakis, Koupidis, Siamouli, Grammatikopoulos and Theodorakis39 An important limitation of most of these studies on European rates is that they analyse the suicide rates from 2007 on and not before, although they do report a nadir for suicide rates during 2007, and they focus almost exclusively on the possible effect of unemployment, thus neglecting other factors.

The Lopez-Ibor Foundation launched an initiative to study the possible impact of the economic crisis on European suicide rates. A group of experts were gathered from participating countries and data concerning suicide rates since 2000, along with economic indices, were gathered and analysed. The hypothesis was that suicide rates correlate with unemployment, growth rate and inflation, which are aspects of the economic situation that have a direct impact on the everyday life of the population and especially of vulnerable groups.

Method

Data acquisition

Data were gathered from 29 European countries (see online Table DS1). The data included number of men and women in the population, number of deaths by suicide in men and women, unemployment rate, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, annual economic growth rate and inflation. All data were collected strictly from the official national statistical agencies of countries. The economic variables used were defined according to the World Bank definitions. Some discrepancies between the data obtained from national agencies and those of Eurostat were detected (for example Poland). The data from the national agencies were used in all instances.

The suicide rates were calculated as number of suicides per 100 000 inhabitants without adjusting for age, since European countries do not differ significantly in terms of age composition of their populations. Adjusting for age and gender on the basis of a standardised population was not feasible since data of this kind were not readily available for all countries and all years.

The unemployment rate refers to the share of the labour force that is without work but available for and seeking employment. Definitions of labour force and unemployment differ by country, but among European countries differences are not large. Typically, the total labour force comprises people ages 15 and older who meet the International Labour Organization definition of the economically active population: all people who supply labour for the production of goods and services during a specified period. It includes both the employed and the unemployed. Although national practices vary in the treatment of such groups as the armed forces and seasonal or part-time workers, in general the labour force includes the armed forces, the unemployed and first-time job-seekers, but excludes homemakers and other unpaid caregivers and workers in the informal sector.

Gross domestic product is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or for depletion and degradation of natural resources.

The annual GDP growth was defined as the annual percentage growth rate of GDP at market prices based on constant local currency. The GDP per capita was defined as GDP divided by mid-year population.

Inflation, as measured by the consumer price index, reflects the annual percentage change in the cost to the average consumer of acquiring a basket of goods and services that may be fixed or changed at specified intervals, such as yearly. The Laspeyres formula is generally used.

All the raw data are shown in online Table DS1, and online Fig. DS1 shows the total suicide rates for each country.

Data analysis

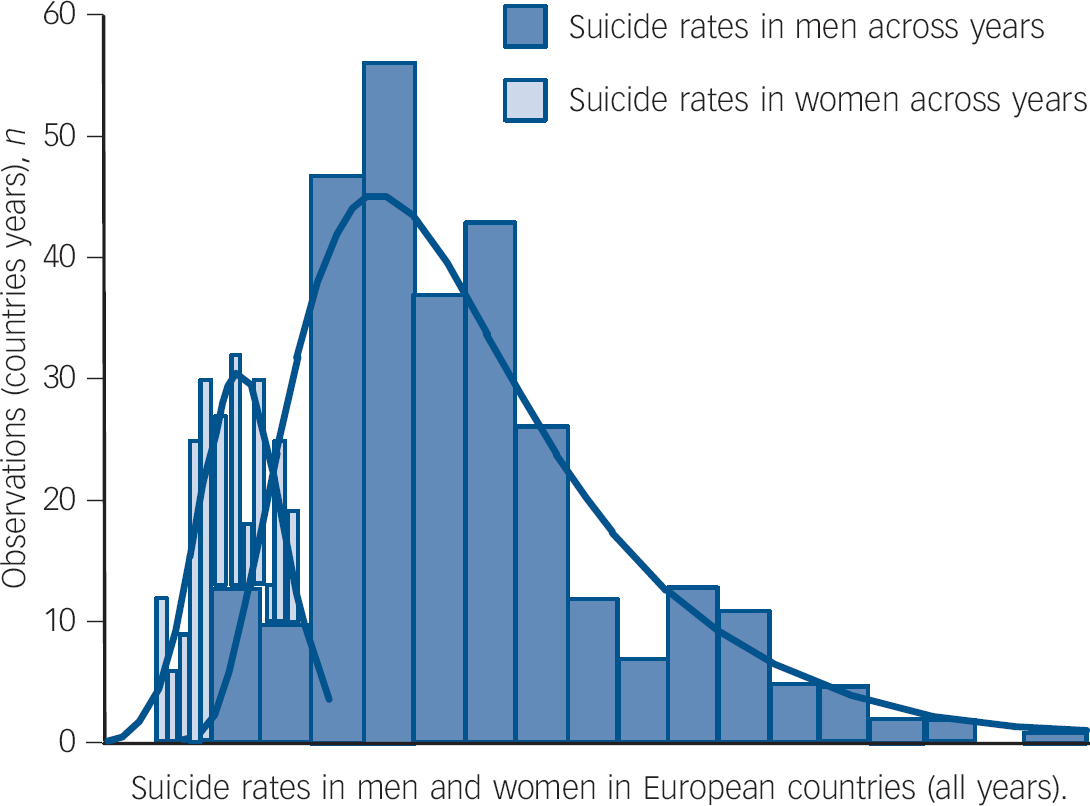

Three sets of data were obtained concerning suicides: the total rate and the rates in men and women. The total and the rates in men followed a loglinear distribution whereas the rate in women followed a normal distribution (Fig. 1).

To allow different time trends of suicide rates between countries a random coefficient regression model was applied. Specifically, we used the procedure NLMIXED in SAS 9.3 for Windows with log as link function. The model error term as well as the two random coefficients (country and country×time) were assumed to be normally distributed. Calendar year was rescaled to be zero in 2000 and GDP per capita was divided by 1000 to enhance estimation of the model as well as interpretation of effects.

Fig. 1 Histogram of suicide rates: pooled data for all countries and all years.

The dependent variables were total suicide rate and rate in men for the first two and rate in women for the third. Country was used as a categorical predictor and the economic variables (unemployment, growth rate, GDP, GDP per capita and inflation) and year as continuous predictors. We chose to use rates rather than numbers as dependent variables for two reasons. First, the use of rates would put all countries at a similar level and would not give any advantage to the big ones, thus preserving the ‘qualitative’ differences between countries. Second, the absolute number of suicides did not fit any of the basic distributions and the models derived had poor goodness-of-fit. Countries with more than 1 year of missing data were not included in the models (Bulgaria, Montenegro, Belgium, Italy).

Following the above multifactorial analyses, several exploratory analyses were applied to the data for each country separately using the non-parametric Spearman correlation coefficient. The calculation of the coefficients was done for the total time span (years 2000-2011) and also for two separate periods (2000-2005 and 2006-2011) since it was obvious that after 2006 a change in suicide trends was evident. The correlations between total suicide rates and rates in men and women with the economic variables mentioned above were calculated for each country separately.

Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA was used to test numerical differences between groups.

Results

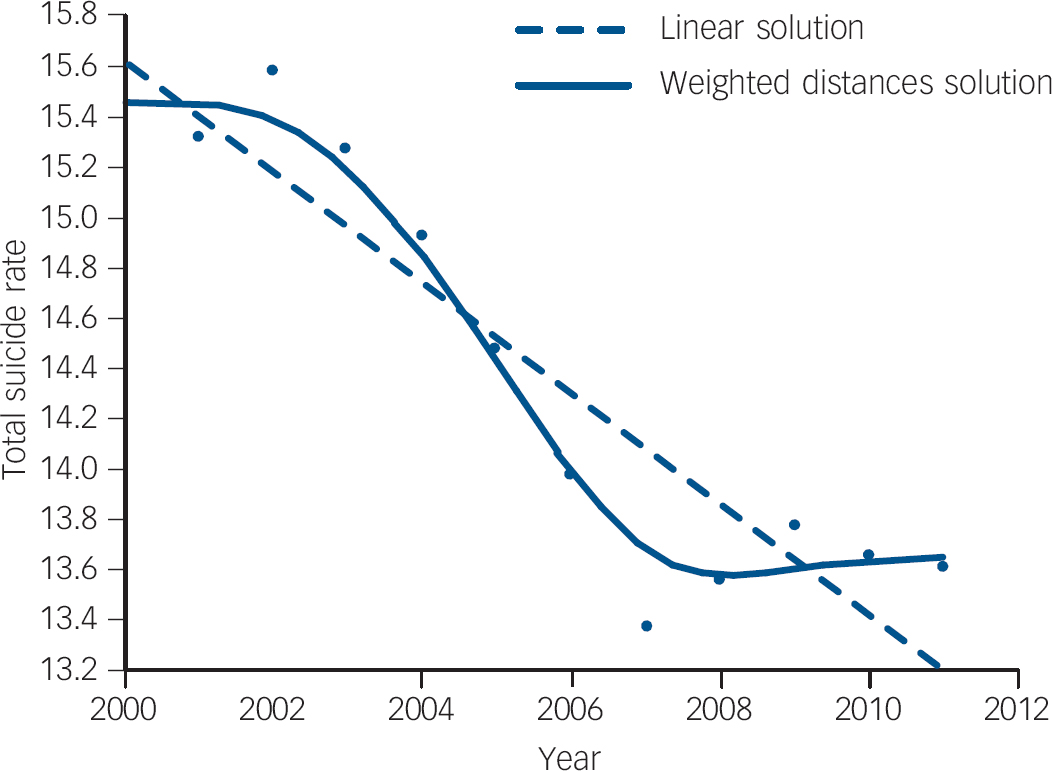

The combined data of European countries for the years 2000-2010 are shown in Table 1 and the evolution of suicides in Europe across the years in Fig. 2. Pooled data from only those countries with 2011 data as well and separately for Eurozone, European Union (EU) and the rest of the European countries can be found in online Table DS1. Online Fig. DS1 shows suicide v. time for individual countries. Overall the data from the 29 countries show a decreasing trend from year 2000 to 2011 for suicide rates both for men and for women (Table 1, Fig. 2, online Table DS1 and online Fig. DS1).

The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 2 for total suicide rates and in Table 3 for men and women separately. They suggest that total suicides rates and rates for men were related to all economic variables except GDP per capita. Rates for women were only related to unemployment. As expected, year and country also had a significant effect.

The inspection of data revealed there was a clear increasing trend in Slovakia. In Greece the maximum rate emerged in 2012 and a stabilising trend seems to be in place. Stable rates across the years were observed in the Netherlands, Romania, Norway, Montenegro and Sweden, whereas the rates for Portugal fluctuated greatly. In the other 21 countries the trend was towards lower overall suicide rates for 2010-2011 in comparison with 2000, however only in 4 of these countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland and Switzerland) was this decrease continuous and un-intermittent (online Table DS1 and online Fig. DS1). With the exception of these 4 countries (Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland and Switzerland), for the other 25 countries the rate of suicides reached a nadir during the years 2006-2009 (Table 4, online Table DS1 and online Fig. DS1). In the countries that manifested this nadir, the rates were unstable for the next year; for some a trend to increase was clear (such as the Netherlands), in others the rates increased for 1-2 years only to further decrease afterwards (such as Spain), whereas in others the rates were more or less stable (such as France). In Spain the 2012 data suggest a 10% decrease, thus further perplexing the picture.

There are no common features, in terms of economy, characterising the four countries with an un-intermittent fall in their suicide rates. Estonia experienced significant recession, Bulgaria and Finland experienced recession to a lesser extent and Switzerland only marginal recession. Slovakia, which is the only country with increasing suicide rates, experienced recession only for 1 year and its unemployment and GPD growth rates have been steadily improving since 2000. It is important to note that Slovenia did not experience any recession after 2005, however, it manifested a nadir of suicide rates in 2008 followed by an increase. Nonetheless, in the same country, in spite of significant recession during the years 2000-2005, at that time the suicide rates were dropping. Montenegro is another interesting example. In that country, the suicide rate remained unchanged throughout 2000-2010, in spite of a high growth rate. In that country the unemployment rate remained high and unchanged as well. Portugal is an exception. It experienced a recession with an increase in the suicide rate in 2003. It is the only country without a clear reduction in the suicide rates during 2000-2011. Its 2011 rate is almost double of that of 2000.

Although the data are complex, three major patterns could be identified (Fig. 3). Pattern A is followed by 13 countries, pattern B by 3 and pattern C by 11 countries (Table 4, online Fig. DS1). Montenegro and Switzerland did not follow any of these patterns. The comparison of pattern A v. pattern C countries suggested there was a tendency for pattern C countries to have better economic indices and lower suicide rates but this difference was not significant. There was also no correlation of unemployment rate at the year of nadir suicide rates and the rate of suicide increase afterwards.

Fig. 2 Change in suicide rates in Europe 2000-2010: pooled data.

Table 1 Pooled data of European countries for the years 2000-2010 (Italy, Montenegro and Bulgaria excluded because of incomplete data)

| Population | Suicides, n | Suicide rate | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Total | Men | Women | Total | Men | Women | Total | Men | Women |

| 2000 | 430 147 247 | 209 459 316 | 220 669 932 | 59 873 | 45 153 | 14 720 | 13.92 | 21.56 | 6.67 |

| 2001 | 431 483 804 | 210 282 349 | 221 201 455 | 58 624 | 44 520 | 14 104 | 13.59 | 21.17 | 6.38 |

| 2002 | 432 729 703 | 210 978 947 | 221 750 756 | 59 592 | 45 072 | 14 520 | 13.77 | 21.36 | 6.55 |

| 2003 | 434 540 344 | 211 934 885 | 222 605 459 | 58 583 | 44 478 | 14 105 | 13.48 | 20.99 | 6.34 |

| 2004 | 435 941 409 | 212 670 297 | 223 271 112 | 57 963 | 43 821 | 14 122 | 13.30 | 20.61 | 6.33 |

| 2005 | 437 969 462 | 213 759 938 | 224 209 524 | 56 325 | 42 515 | 13 810 | 12.86 | 19.89 | 6.16 |

| 2006 | 439 537 845 | 214 600 383 | 224 936 462 | 53 895 | 40 872 | 13 011 | 12.26 | 19.05 | 5.78 |

| 2007 | 441 202 320 | 215 434 814 | 225 687 506 | 51 615 | 39 140 | 12 485 | 11.70 | 18.17 | 5.53 |

| 2008 | 443 251 055 | 216 648 416 | 226 603 639 | 53 376 | 40 684 | 12 692 | 12.04 | 18.78 | 5.60 |

| 2009 | 444 825 169 | 217 452 639 | 227 373 530 | 54 437 | 42 154 | 12 012 | 12.24 | 19.39 | 5.28 |

| 2010 | 446 575 604 | 218 367 743 | 228 207 924 | 53 504 | 41 221 | 12 283 | 11.98 | 18.88 | 5.38 |

From the above it is evident that the great majority of countries manifested a halt in their decreasing suicide rates with a nadir in rates during the years 2006-2008, followed by an increase, which in half of them was temporary. The temporal relationship of this nadir in the decreasing rates to the onset of recession for each country is shown in Table 4. Onset of recession could be defined here as either a negative sign of growth rate or an increase in unemployment (see online Table DS1). The duration of this recession for each country is also shown in Table 4. In 23 countries the nadir in suicides occurred clearly before and in only 2 it occurred after the recession had started.

The mean occurrence of nadir was early 2007 whereas the mean onset of recession was mid-2008. The average latency time from suicide nadir to recession onset was 1.44 years (17.3 months, s.d. = 0.82 years). The average latency time to recession according to GDP was 1.44 years (17.3 months, s.d. = 0.84 years) and to recession according to the unemployment increase was 1.72 years (20.6 months, s.d. = 0.98 years). There were no differences between rates in men and women for this issue. All latency times were greater than 1 year, suggesting that clearly the change in slope of the suicide line occurred some months before the respected change in the slope of economic indices.

The Spearman correlation coefficients separately for each country, for total suicide rates and rates for men and women and economic indices, are shown in Table 5. The coefficients are also shown in online Table DS1 together with the coefficients calculated separately for the years 2000-2005 and 2006-2011. The coefficients with values over 0.5 (arbitrary chosen) are shown in Table 4. Some countries kept the same coefficients in this sub-analysis but others did not. This sub-analysis should be considered to be purely exploratory.

The correlation coefficient results suggest that the suicide rates are strongly correlated with GDP per capita and its changes and to a lesser extent with unemployment, which is in sharp contrast to the regression analysis results. Some countries (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Montenegro, Norway and Serbia) show very weak correlations of the suicide rates with economic indices.

In Table 6 the correlation coefficients between suicide rates and economic variables across countries for the same year are shown. Overall correlations are weak, with GDP per capita and unemployment showing some stronger tendencies.

Discussion

Main findings

Suicide rates have increased dramatically over the past 45 years despite prevention efforts. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40 There is marked geographic variability in suicide rates, with the highest rates being found in Eastern Europe and some US states and the lowest in Muslim and Latin American countries. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40,Reference Tondo, Albert and Baldessarini41 So far, this variability in suicide rates has not been satisfactorily explained. This variability is particularly true for the continent of Europe. Reasons for these great differences between national/regional suicide rates have not been fully explained yet. Geographic (latitude, longitude, altitude) climatic, dietary, genetic, economic, religious and other sociocultural differences can be taken into account. However, differences in psychiatric morbidity, the accuracy of the registration of suicide, the stigma associated with mental illness and suicide (possibly influencing help-seeking behaviour and reporting rates), the availability of lethal methods, and the availability of the social and healthcare systems should be considered. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40,Reference Rihmer, Kantor, Rihmer and Seregi42

Table 2 Results of the regression analyses for total suicide ratesFootnote a

| Total suicide rates | Estimate | s.e. | t-value | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.8898 | 0.1033 | 18.3 | <0.0001 |

| GDP per capita /1000 | –0.00256 | 0.001492 | –1.72 | 0.0921 |

| National unemployment rate | 0.005579 | 0.00106 | 5.26 | <0.0001 |

| National growth rate | –0.00401 | 0.000639 | –6.28 | <0.0001 |

| Inflation | –0.00327 | 0.001195 | –2.74 | 0.0086 |

| Year - 2000 | –0.0189 | 0.00363 | –5.21 | <0.0001 |

| Men | 1.3839 | 0.1171 | 11.82 | <0.0001 |

| D11Footnote b | 0.3202 | 0.06805 | 4.71 | <0.0001 |

| D21Footnote c | –0.00871 | 0.002457 | –3.54 | 0.0009 |

| D22Footnote d | 0.000408 | 0.000112 | 3.64 | 0.0007 |

| Error | 1.482 | 0.09553 | 15.51 | <0.0001 |

| –2 Log-likelihood | 2258.8 |

GDP, gross domestic product.

a. With country and country year as random effects. Total suicide rates are related to all economic variables. As expected, year and country also had a significant effect, except for Romania and Switzerland.

b. D11 is the estimated random variance of the country-specific intercepts.

c. D21 is the covariance of D1 and D2. It is a very common finding in longitudinal regression analysis that there is a negative covariance between intercept and slope.

d. D22 is the estimated random variance of the country-specific time trends.

Table 3 Results of the regression analyses for suicide rates in men and womenFootnote a

| Estimate | s.e. | t-value | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates in men | ||||

| Intercept | 3.2261 | 0.1167 | 27.64 | <0.0001 |

| GDP per capita /1000 | –0.00387 | 0.001876 | –2.06 | 0.0506 |

| National unemployment rate | 0.005096 | 0.001369 | 3.72 | 0.0011 |

| National growth rate | –0.00412 | 0.000831 | –4.96 | <0.0001 |

| Inflation | –0.00347 | 0.001527 | –2.27 | 0.0328 |

| Year - 2000 | –0.01405 | 0.004467 | –3.14 | 0.0045 |

| D11Footnote b | 0.3096 | 0.08933 | 3.47 | 0.0021 |

| D21Footnote c | –0.00852 | 0.002999 | –2.84 | 0.0093 |

| D22Footnote d | 0.00035 | 0.000124 | 2.83 | 0.0094 |

| Error | 2.3952 | 0.2185 | 10.96 | <0.0001 |

| –2 Log-likelihood | 1293.1 | |||

| Rates in women | ||||

| Intercept | 1.8225 | 0.1265 | 14.41 | <0.0001 |

| GDP per capita /1000 | 0.004294 | 0.002657 | 1.62 | 0.1197 |

| National unemployment rate | 0.008235 | 0.002745 | 3 | 0.0064 |

| National growth rate | –0.0024 | 0.001814 | –1.33 | 0.1981 |

| Inflation | 0.000872 | 0.00309 | 0.28 | 0.7804 |

| Year - 2000 | –0.03169 | 0.005815 | –5.45 | <0.0001 |

| D11Footnote b | 0.3209 | 0.09687 | 3.31 | 0.003 |

| D21Footnote c | –0.00695 | 0.003761 | –1.85 | 0.0775 |

| D22Footnote d | 0.000448 | 0.000171 | 2.62 | 0.0154 |

| Error | 0.5432 | 0.04908 | 11.07 | <0.0001 |

| –2 Log-likelihood | 829.6 |

GDP, gross domestic product.

a. With country and country year as random effects. Rates in men are related to all economic variables. Rates in women are not related to the national growth rate. As expected, year and country also had a significant effect, except for Poland for rates in men.

b. D11 is the estimated random variance of the country-specific intercepts.

c. D21 is the covariance of D1 and D2. It is a very common finding in longitudinal regression analysis that there is a negative covariance between intercept and slope.

d. D22 is the estimated random variance of the country-specific time trends.

The current study analysed the correlation between suicide rates in 29 European countries and economic indices. Although a correlation is evident, the temporal relationships do not support a direct link between the economic crisis and any change in the suicide rates. It also found the following results.

-

(a) There was a nadir for suicide rates across Europe around the year 2007. This synchronisation cannot be considered to be random; instead some common aetiology should have influenced the rates across the continent.

-

(b) Even in countries with more or less stable rates, the specific nadir was evident.

-

(c) The nadir occurred more than a year before the onset of the economic crisis and the subsequent increase in suicide rates also occurred several months before the crisis.

-

(d) There was a strong correlation of suicide rates with all economic indices except GDP per capita in men but only with unemployment in females. For the vast majority of countries the suicide rates correlated strongly with GDP per capita and rather weakly with unemployment and the other indices. This correlation was strong within each country and less strong across countries.

-

(e) In Eurozone countries the correlation with GDP per capita was the dominant pattern. In the rest of EU countries the correlation with unemployment was also strong. In countries outside the EU, the correlation of suicide rates with economic variables was weak.

-

(f) The combined data from European countries for the years 2000-2010 (Table 1 and online Table DS1 and online Fig. DS1) suggest that the average suicide rate in the European region is similar to that reported for the USA.

Table 4 Year of nadir in suicide rates and onset of recession according to two indices (growth rate and unemployment and duration of recession according to each one) as well as pattern of suicide rates evolution and correlations between suicide rates and economic indices in European countries

| Year of suicide rate nadir |

Recession indices, start year (duration in years) |

Timing of nadir in suicide rates |

Correlations between total suicide rate and economic indices |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Men | Women | Growth rate |

Unemploy- ment |

Pattern | Before recession started |

After recession started |

National unemployment rate |

National growth rate |

GDP (per capita) |

Inflation | |

| Eurozone countries | ||||||||||||

| Austria | 2010 | 2010 | 2010 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (3) | A | + | –0.90 | ||||

| Belgium | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (2) | B | + | –0.81 | ||||

| Estonia | - | - | - | 2008 (2) | 2009 (3) | A | –0.90 | |||||

| Finland | - | - | - | 2009 (1) | 2010 (3) | A | 0.72 | –0.89 | ||||

| France | 2007 | 2007 | 2011 | 2008 (2) | 2009 (3) | A | + | –0.85 | ||||

| Germany | 2007 | 2007 | 2006 | 2009 (1) | 2011 (1) | C | + | –0.77 | ||||

| Greece | 2007 | 2007 | 2010 | 2009 (3) | 2009 (3) | A | + | |||||

| Italy | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 2008 (2) | 2008 (2) | C | + | 0.86 | –0.83 | |||

| Ireland | 2007 | 2007 | 2006 | 2008 (3) | 2008 (4) | C | + | –0.56 | –0.71 | |||

| Netherlands | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (3) | C | + | |||||

| Portugal | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 2008 (2) | 2009 (3) | C | + | |||||

| Slovakia | 2006 | 2006 | 2006 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (2) | C | + | –0.58 | 0.73 | –0.58 | ||

| Slovenia | 2008 | 2008 | 2010 | - | 2009 (3) | C | + | 0.56 | –0.82 | –0.94 | 0.63 | |

| Spain | 2007 | 2007 | 2006 | 2009 (2) | 2008 (3) | B | + | |||||

| European Union, non-Eurozone countries | ||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | 2009 | 2010 | 2009 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (2) | A | + | 0.81 | –0.66 | |||

| Croatia | 2007 | 2007 | 2009 | 2009 (2) | 2009 (3) | C | + | 0.76 | –0.79 | |||

| Czech Rep | 2008 | 2008 | 2007 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (2) | C | + | 0.59 | –0.82 | |||

| Denmark | 2007 | 2007 | 2005 | 2008 (2) | 2009 (3) | A | + | –0.92 | ||||

| Hungary | 2007 | 2006 | 2010 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (3) | A | + | –0.79 | 0.63 | –0.87 | 0.52 | |

| Latvia | 2007 | 2007 | 2006 | 2008 (3) | 2008 (4) | A | + | –0.84 | ||||

| Lithuania | 2007 | 2006 | 2007 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (3) | A | + | –0.86 | –0.78 | |||

| Poland | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | - | 2009 (2) | C | + | 0.79 | –0.62 | –0.74 | ||

| Romania | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2009 (2) | 2009 (3) | A | + | 0.59 | –0.63 | 0.57 | ||

| Sweden | 2007 | 2007 | 2008 | 2008 (2) | 2009 (3) | B | + | –0.57 | ||||

| UK | 2007 | 2007 | 2007 | 2008 (2) | 2009 (2) | A | + | –0.80 | ||||

| Non-European union countries | ||||||||||||

| Montenegro | - | - | - | - | 2009 (1) | - | ||||||

| Norway | 2007 | 2007 | 2006 | 2008 (4) | 2009 (3) | C | + | |||||

| Serbia | 2008 | 2008 | 2010 | 2009 (1) | 2009 (3) | A | + | |||||

| Switzerland | - | - | - | 2009 (1) | 2009 (2) | - | –0.52 | 0.61 | ||||

GDP, gross domestic product.

Fig. 3 Patterns of change in suicide data in European countries in relation to the 2007 nadir.

Pattern A: the declining suicide rate is followed by a temporal increase after 2007 and then stabilises; in pattern B the declining suicide rate is interrupted by a temporal increase after 2007 and then the decline continues; in pattern C the declining suicide rate is reversed after 2007.

Table 5 Correlation coefficients between suicide rates and economic indices for each European country

| Total suicide rate | Suicide rate in men | Suicide rate in women | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | National unemploy- ment rate |

National growth rate |

GDP (per capita) |

Inflation | National unemploy- ment rate |

National growth rate |

GDP (per capita) |

Inflation | National unemploy- ment rate |

National growth rate |

GDP (per capita) |

Inflation |

| Eurozone countries | ||||||||||||

| Austria | –0.31 | 0.05 | –0.90 | –0.09 | –0.29 | 0.01 | –0.89 | –0.11 | –0.41 | –0.12 | –0.80 | 0.07 |

| Belgium | 0.26 | –0.33 | –0.81 | 0.00 | 0.26 | –0.33 | –0.81 | 0.00 | 0.32 | –0.48 | –0.86 | –0.38 |

| Estonia | 0.17 | 0.11 | –0.90 | –0.22 | 0.19 | 0.01 | –0.87 | –0.27 | 0.03 | 0.24 | –0.85 | –0.05 |

| Finland | 0.72 | –0.08 | –0.89 | 0.07 | 0.68 | –0.05 | –0.86 | 0.10 | 0.77 | 0.00 | –0.90 | –0.16 |

| France | –0.25 | 0.26 | –0.85 | 0.29 | –0.22 | 0.19 | –0.80 | 0.32 | –0.47 | 0.36 | –0.82 | 0.27 |

| Germany | 0.10 | 0.00 | –0.80 | –0.24 | 0.03 | –0.00 | –0.75 | –0.24 | 0.26 | 0.01 | –0.87 | –0.22 |

| Greece | 0.23 | –0.07 | 0.04 | –0.08 | 0.24 | –0.36 | 0.38 | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.33 | –0.38 | –0.15 |

| Italy | 0.94 | 0.22 | –0.91 | 0.38 | 0.89 | 0.06 | –0.84 | 0.28 | 0.90 | 0.47 | –0.91 | 0.49 |

| Ireland | –0.56 | 0.14 | –0.71 | 0.25 | –0.46 | 0.10 | –0.73 | 0.11 | –0.16 | –0.09 | –0.07 | 0.09 |

| Netherlands | 0.27 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.17 | –0.08 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.11 | –0.51 | 0.35 |

| Portugal | 0.13 | –0.39 | 0.16 | –0.05 | 0.19 | –0.45 | 0.14 | –0.08 | 0.23 | –0.19 | 0.23 | –0.22 |

| Slovakia | –0.58 | –0.25 | 0.73 | –0.58 | –0.62 | –0.31 | 0.74 | –0.66 | 0.14 | –0.24 | –0.03 | 0.34 |

| Slovenia | 0.56 | –0.82 | –0.94 | 0.63 | 0.60 | –0.83 | –0.90 | 0.58 | 0.39 | –0.73 | –0.85 | 0.59 |

| Spain | 0.06 | 0.34 | –0.41 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.25 | –0.35 | 0.04 | –0.17 | 0.48 | –0.31 | 0.55 |

| European union, non-Eurozone countries | ||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | 0.14 | 0.81 | –0.66 | 0.43 | –0.11 | 0.64 | –0.43 | 0.37 | –0.11 | 0.55 | –0.37 | 0.60 |

| Croatia | 0.76 | 0.26 | –0.79 | 0.12 | 0.59 | 0.18 | –0.73 | 0.10 | 0.69 | 0.33 | –0.73 | 0.23 |

| Czech Rep | 0.59 | 0.01 | –0.82 | –0.17 | 0.61 | –0.01 | –0.81 | –0.16 | 0.43 | 0.05 | –0.85 | 0.04 |

| Denmark | –0.36 | 0.26 | –0.94 | 0.01 | –0.10 | 0.11 | –0.91 | 0.14 | –0.59 | 0.44 | –0.65 | 0.17 |

| Hungary | –0.79 | 0.63 | –0.87 | 0.52 | –0.77 | 0.57 | –0.88 | 0.57 | –0.81 | 0.79 | –0.72 | 0.45 |

| Latvia | 0.11 | 0.04 | –0.84 | –0.37 | 0.13 | 0.02 | –0.87 | –0.43 | 0.00 | 0.11 | –0.81 | –0.32 |

| Lithuania | 0.39 | –0.01 | –0.86 | –0.78 | 0.30 | 0.08 | –0.82 | –0.77 | 0.39 | 0.17 | –0.82 | –0.56 |

| Poland | 0.79 | –0.62 | –0.74 | –0.06 | 0.78 | –0.66 | –0.71 | –0.04 | 0.72 | –0.46 | –0.83 | –0.01 |

| Romania | 0.59 | 0.04 | –0.63 | 0.57 | 0.63 | 0.10 | –0.49 | 0.42 | 0.25 | 0.27 | –0.45 | 0.54 |

| Sweden | –0.15 | –0.41 | –0.57 | –0.38 | –0.22 | –0.51 | –0.41 | –0.17 | –0.11 | –0.24 | –0.52 | –0.42 |

| UK | –0.39 | 0.46 | –0.34 | –0.80 | –0.31 | 0.48 | –0.40 | –0.78 | –0.54 | 0.42 | –0.16 | –0.67 |

| Non-European union countries | ||||||||||||

| Montenegro | 0.25 | 0.11 | –0.07 | 0.36 | 0.61 | 0.18 | –0.18 | 0.18 | –0.07 | –0.47 | –0.33 | 0.53 |

| Norway | 0.17 | 0.17 | –0.26 | 0.22 | 0.03 | –0.03 | –0.42 | 0.39 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.54 | –0.23 |

| Serbia | –0.46 | 0.19 | –0.10 | 0.29 | –0.43 | 0.16 | –0.23 | 0.36 | –0.55 | 0.33 | 0.08 | 0.28 |

| Switzerland | –0.52 | –0.04 | 0.61 | 0.23 | –0.51 | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.37 | –0.51 | 0.03 | 0.64 | 0.31 |

GDP, gross domestic product.

Several conclusions can be made on the basis of the above. First, these data clearly dispute the assumption that specifically changes in unemployment have a direct effect on suicide rates. The temporal sequence and correlation of events (suicide rise first, economic recession follows, synchronisation of suicide rate changes across the continent) suggests there is a close relationship between the economic environment and suicide rates; however this relationship is not that of a direct cause and effect. The findings reported by the present study concerning Europe are similar to those reported for the USA. In spite of claims that the rise in unemployment caused a rise in the suicide rate in the USA, Reference Reeves, Stuckler, McKee, Gunnell, Chang and Basu34 a closer look at the data revealed that suicides rose first and unemployment followed. Reference Fountoulakis, Koupidis, Siamouli, Grammatikopoulos and Theodorakis39 One could argue that those people who are going to lose their jobs are stressed months before this happens, but ‘fear’ of unemployment is quite different from unemployment per se, especially since such an assumption suggests that employed people take their own life before they become unemployed.

Second, it is certain that an ‘event’ occurred in the European continent after 2005 and had a profound effect on suicide rates, probably by halting the ongoing reduction in suicide rates. The strong correlation of these rates with GDP per capita and the weaker but still important correlation with the other economic indices suggest that this event was probably the prodromal phase of the economic crisis. Unfortunately, no data concerning this ‘prodrome’ can be found in the literature.

It is important however to place a question mark on the nature of the 2007 nadir in the suicide rates. This nadir was evident as a sharp decline from previous year even in countries with otherwise low and stable suicide rates until that time (such as Greece) or in countries with a robust increasing trend (such as Slovakia).

Third, an important and robust finding of the current study was the strong correlation of suicide rates with GDP per capita, although such an effect was not detected by the regression analysis. This correlation was of the magnitude of 0.80 and was found in the vast majority of countries with independent calculations. The correlation was strong within countries and weaker across countries (and also in the regression models) suggesting that the GDP is related to fluctuations in the suicide rates but may not be with the absolute baseline value. Unemployment was more important for countries outside the Eurozone area. This pattern is rather difficult to interpret.

The GDP was first developed in 1934 by Simon Kuznets Reference Kuznets43 and the danger of using it as a measure of welfare was pointed out by the author. It was established as the main tool to measure a country’s economy in 1944 after the Bretton Woods conference. In spite of the early warnings, the GDP per capita is often used as a measurement of the standard of living. This is based on the assumption that all citizens would benefit from the economic growth of their country. However, essentially it is not such an indicator and it is not a measure of personal income, since it does not take into consideration the inequalities within a given country. Nevertheless, a similar index, the gross national income (GNI) per capita is included as a significant contributor to the Human Development Index (HDI). 44 In this paper, all the economic indices checked by the authors (Gini index, private debt % of GDP, HDI) did not manifest any pattern that would relate them to the change in the suicide rates trends after 2007.

Table 6 Correlation between suicide rates and economic variables across countries during the same year

| Suicide rate |

National unemployment rate |

National growth rate |

GDP (per capita) |

Inflation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | ||||

| Total | 0.28 | –0.04 | –0.32 | 0.03 |

| Men | 0.31 | –0.02 | –0.36 | 0.09 |

| Women | 0.17 | –0.04 | –0.22 | –0.12 |

| 2001 | ||||

| Total | 0.29 | 0.14 | –0.34 | –0.09 |

| Men | 0.37 | 0.20 | –0.43 | 0.00 |

| Women | 0.23 | 0.01 | –0.28 | –0.12 |

| 2002 | ||||

| Total | 0.26 | 0.30 | –0.44 | –0.13 |

| Men | 0.29 | 0.32 | –0.46 | –0.13 |

| Women | 0.10 | 0.12 | –0.25 | –0.21 |

| 2003 | ||||

| Total | 0.24 | 0.24 | –0.39 | –0.20 |

| Men | 0.33 | 0.31 | –0.48 | –0.20 |

| Women | 0.13 | 0.03 | –0.22 | –0.26 |

| 2004 | ||||

| Total | 0.23 | 0.29 | –0.42 | 0.12 |

| Men | 0.29 | 0.41 | –0.51 | 0.26 |

| Women | 0.06 | 0.06 | –0.20 | –0.18 |

| 2005 | ||||

| Total | 0.25 | 0.28 | –0.38 | 0.08 |

| Men | 0.30 | 0.35 | –0.47 | 0.15 |

| Women | 0.12 | 0.02 | –0.17 | –0.15 |

| 2006 | ||||

| Total | 0.13 | 0.23 | –0.34 | –0.02 |

| Men | 0.21 | 0.31 | –0.45 | 0.07 |

| Women | 0.07 | –0.05 | –0.14 | –0.27 |

| 2007 | ||||

| Total | 0.00 | 0.19 | –0.33 | 0.37 |

| Men | 0.06 | 0.30 | –0.43 | 0.46 |

| Women | –0.01 | –0.03 | –0.15 | 0.11 |

| 2008 | ||||

| Total | 0.13 | 0.09 | –0.39 | 0.42 |

| Men | 0.20 | 0.14 | –0.46 | 0.45 |

| Women | 0.03 | –0.04 | –0.20 | 0.18 |

| 2009 | ||||

| Total | 0.35 | –0.36 | –0.30 | 0.00 |

| Men | 0.42 | –0.35 | –0.42 | 0.05 |

| Women | 0.17 | –0.27 | –0.13 | –0.03 |

| 2010 | ||||

| Total | 0.22 | –0.11 | –0.41 | –0.09 |

| Men | 0.34 | –0.04 | –0.49 | –0.08 |

| Women | –0.09 | –0.02 | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| 2011 | ||||

| Total | 0.50 | 0.32 | –0.46 | 0.13 |

| Men | 0.51 | 0.39 | –0.54 | 0.28 |

| Women | 0.41 | 0.18 | –0.20 | –0.10 |

One previous study reported that cross-sectionally the GDP per capita had a tendency to correlate with suicide rates in males (r = 0.3, P = 0.06) but not in females (r = 0.2, P = 0.9). Reference Sher45 Our results are in accord with this. However, the relationship of GDP with suicidality seems to be more complex and it might follow an inverted U-shaped curve, with suicide trends declining after peaking at a certain threshold of economic development. Reference Moniruzzaman and Andersson46 At low GDP levels, increases in GDP are associated with increases in suicide rates, but once a given threshold of economic development is reached, further increases in GDP do not correlate with further increases in suicide rates. Reference Voracek47

Overall, there was a worldwide increase in the purchasing power parity-adjusted GDP per capita over the past 3 decades, and during the same time period the suicide rates have increased in developing Latin American and Caribbean countries and in several high-income Asian countries (such as Japan and South Korea), and have decreased in the majority of European countries and Canada. Reference Blasco-Fontecilla, Perez-Rodriguez, Garcia-Nieto, Fernandez-Navarro, Galfalvy and de Leon48 Suicide rates in India were also positively correlated with GDP rates although the quality of the data is low and should be interpreted with caution. Reference Soman, Safraj, Kutty, Vijayakumar and Ajayan49-Reference Jacob, Sharan, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera, Seedat and Mari53 Concerning Japan and South Korea, they are both high-income countries with universal health coverage but with the private health sector prevailing over public health resources. In South Korea, although life expectancy has rapidly increased, mortality as a result of suicide increased, particularly among men aged 30 years or older. Reference Yang, Khang, Harper, Davey Smith, Leon and Lynch54

It seems that economic growth is not invariably followed by a decrease in suicide rates, especially because income inequality causes them to increase. Reference Chen, Choi and Sawada55 Also if economic growth is not accompanied by adequate infrastructures for mental health services, suicide rates might trend up. Reference Jacob, Sharan, Mirza, Garrido-Cumbrera, Seedat and Mari53

Suicide rates and mental illness

When studying the possible causes of suicide, one should have in mind that suicide is probably the end result of an interaction between many different risk factors with mental disorders being the decisive one. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40,Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen56 It is solidly proven that over 90% of people who die from suicide have a mental illness. Mood disorders are found in 80-85% Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40,Reference Rihmer, Kantor, Rihmer and Seregi42,Reference Gray and Otto57 and schizophrenia in 9-13% of people dying each year because of suicide. Reference Meltzer58 The significance of mental disorders may be much smaller in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Manoranjitham, Rajkumar, Thangadurai, Prasad, Jayakaran and Jacob59 Other risk factors in the field of psychiatry also exist, including personality disorders and substance and alcohol dependence, Reference Oquendo, Bongiovi-Garcia, Galfalvy, Goldberg, Grunebaum and Burke60,Reference Comtois, Russo, Roy-Byrne and Ries61 and a family history of suicide. Reference Oquendo, Bongiovi-Garcia, Galfalvy, Goldberg, Grunebaum and Burke60,Reference Cavazzoni, Grof, Duffy, Grof, Muller-Oerlinghausen and Berghofer62,Reference Hawton, Sutton, Haw, Sinclair and Harriss63 Ethnic group, Reference Kupfer, Frank, Grochocinski, Houck and Brown64 problematic coping skills Reference Johnson, Lydiard, Morton, Laird, Steele and Kellner65 and environmental variables such as recent psychosocial stress Reference Leverich, Altshuler, Frye, Suppes, Keck and McElroy66,Reference Leverich, McElroy, Suppes, Keck, Denicoff and Nolen67 and occupational problems or interpersonal problems with spouses or romantic partners Reference Tsai, Lee and Chen68 also constitute risk factors. The availability and access to lethal means (such as firearms) might be of importance. Reference Rihmer, Kantor, Rihmer and Seregi42 Theoretically, any intervention that helps reducing these risk factors could ultimately reduce the suicide rate; however this has not been solidly proven for most of these variables. Reference Mann, Apter, Bertolote, Beautrais, Currier and Haas40 Unfortunately, research on suicide is limited by the fact that the majority of suicide victims die at the first attempt. Reference Rihmer, Belso and Kiss69,Reference Isometsa, Henriksson, Aro, Heikkinen, Kuoppasalmi and Lonnqvist70

The first to suggest that the suicide rate depends on socioeconomic driving forces was Enrico Agostino Morselli in 1882. Reference Morselli71 Since then, suicide has usually been considered a social problem, and several risk factors have been related to suicidal behaviour, both at the subject level (microsocioeconomic factors) and at the state level (macrosocioeconomic level). Reference Qin, Agerbo and Mortensen56,Reference Lester and Yang72

Suicide prevention

An example of a successful programme aiming to reduce suicide rates is the National Service Framework target set in the UK in 1999, which aimed to reduce suicides by at least 20% by 2010. This target was achieved. The interventions included awareness campaigns and encouragement particularly to general practitioners to recognise depression and treat it early, especially with the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. However, in the USA and the Netherlands the official warning in 2003-4 was against prescribing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for young people, and this was followed by a reduction in prescribing and a detected increase in suicides in that age group. Reference Gibbons, Brown, Hur, Marcus, Bhaumik and Erkens73 In Slovenia an increase in antidepressant use lead to a decrease in the suicide rate Reference Korosec Jagodic, Rokavec, Agius and Pregelj74 and this seems to be true for Sweden, Reference Isacsson, Holmgren, Osby and Ahlner75,Reference Isacsson and Ahlner76 Hungary, Reference Dome, Kapitany, Ignits, Porkolab and Rihmer77 Europe as a whole Reference Gusmao, Quintao, McDaid, Arensman, Van Audenhove and Coffey78 and all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries. Reference Kamat, Edgar, Niblock, McDowell and Kelly79,Reference Ludwig, Marcotte and Norberg80 It seems that in spite of potential problems, the use of antidepressants overall decreases suicide rates. Reference Ludwig and Marcotte81

Most of the risk factors are likely to be dependent on the victim’s behaviour and thus do not constitute independent factors, Reference Isometsa, Heikkinen, Henriksson, Aro and Lonnqvist82 however the recent economic crisis constitutes a stress factor that is independent of the behaviour of the person, although people with specific behaviours (such as great risk-taking entrepreneurs) are likely to be more vulnerable to the crisis. On the other hand, specific cultures (such as Hispanic people in the USA) seem to have some kind of protective effects against suicidal behaviour. Reference Oquendo, Dragatsi, Harkavy-Friedman, Dervic, Currier and Burke83 Additional support for this comes from the conclusion of a recent review that only the creation of social support networks reduces suicidality and that other interventions are of unproven effectiveness. Reference Fountoulakis, Gonda and Rihmer84-Reference Gonda, Fountoulakis, Kaprinis and Rihmer87 Although it has been suggested that a reduction in unemployment through governmental action should lead to a reduction in suicidality, Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee88 this remains an unproven theoretical suggestion, and is not supported by the results of the current study.

Findings from other studies

In his seminal work in 1979, Brenner reported that for every 10% increase in unemployment there is an increase of 1.2% in total mortality, including an increase by 1.7% in suicidality. Reference Brenner and Barrett89 Suicide rates are lower in Western high-income countries in comparison with low- and middle-income countries. Reference Jacob90 The relationship of suicide rates with GDP suggests that suicide rates drop in times of economic expansion and increase in times of recession. Reference Tapia Granados91 It has been argued that business cycles affect suicide rates in the USA with the overall suicide rate usually rising during recessions and falling during expansions. Reference Luo, Florence, Quispe-Agnoli, Ouyang and Crosby25 In the past, economic crises have been correlated with increases in suicides, such as the Great depression, Reference Swinscow21,Reference Morrell, Taylor, Quine and Kerr23,Reference Stuckler, Meissner, Fishback, Basu and McKee92,Reference Tapia Granados and Diez Roux93 the Russian crisis in the early 1990s Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell33 (although the data are not published reliably) and the Asian economic crisis in the late 1990s. Reference Chang, Gunnell, Sterne, Lu and Cheng26,Reference Chang, Sterne, Huang, Chuang and Gunnell27 On the contrary, other authors suggested that actually recessions improve several health indicators. 94-Reference Ruhm96 Concerning the present economic crisis, it has been calculated that close to 5000 excess suicides occurred in the year 2009, with the increase consisting mainly of men of working age and with unemployment a direct causal factor. Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell33 A deterioration in mental health with increasing depression and anxiety rates has been reported after the economic crisis in Hong Kong, Reference Lee, Guo, Tsang, Mak, Wu and Ng97 south Australia, Reference Shi, Taylor, Goldney, Winefield, Gill and Tuckerman98 Greece, Reference Economou, Madianos, Peppou, Patelakis and Stefanis99 UK Reference Katikireddi, Niedzwiedz and Popham15 and Spain, Reference Gili, Roca, Basu, McKee and Stuckler30 and the effect seemed more severe in population groups who experienced unstable employment or financial problems. Reference Gili, Roca, Basu, McKee and Stuckler30,Reference Lee, Guo, Tsang, Mak, Wu and Ng97,Reference Shi, Taylor, Goldney, Winefield, Gill and Tuckerman98 However, the methodology of these studies cannot differentiate between general distress and clinical mood disorders and thus any link of these results with the suicide rates is problematic.

Variations between countries in suicide rates

There are considerable variations in the effect of the crisis on the suicide rate across countries and it is unclear whether these variations relate to the severity of the recession as well as to varying social support and labour market protections in different countries, as it has been previously suggested. Reference Stuckler, Basu and McKee12,Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell33,Reference Stuckler, Basu, Suhrcke, Coutts and McKee88 We were also unable to reproduce the finding that there are stronger associations between increases in national suicide rates and unemployment rates in countries with low baseline unemployment rates than in countries with high unemployment rates. Reference Chang, Stuckler, Yip and Gunnell33 On the contrary, we found that the baseline suicide rate was correlated with the overall pattern of the curve of suicide rates after the nadir year.

Social capital

One area that deserves further research is that of the so called ‘social capital’. Overall, the results of the current study imply that there were profound changes within the society of all European countries that preceded the economic crisis, however they were probably related to it or they might even constitute part of its aetiopathogenesis. The ‘social capital’ theory refers to the importance for the community of building generalised trust and, at the same time, the importance of individual free choice, in order to create a more cohesive society. It could be defined as ‘the aggregate of the actual or potential resources which are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition’. Reference Portes100-Reference Ferragina102 A decline in social capital is considered to be at the core of modern socioeconomic problems. Reference Jain, Goyal, Fox and Shrank103-Reference Putnam105 Social cohesion has already been recognised as a factor influencing the suicide rate. Reference Balint, Dome, Daroczi, Gonda and Rihmer106

Limitations

The current study has a number of limitations. It is an observational analysis based on aggregate data collected from national statistical agencies. Probably there are differences between countries both in the quality of the data as well as in the level of misclassification of suicide, and these could lead to potential bias between countries, Reference Kapusta, Tran, Rockett, De Leo, Naylor and Niederkrotenthaler107 but it is not expected they had a significant impact on the results of the current study.

Cross-level bias and aggregation bias are typical of studies similar to the current one. Reference Moniruzzaman and Andersson108 The effects observed at the aggregate level might be modulated by the ecological context at the level of the individual. Reference Lucey, Corcoran, Keeley, Brophy, Arensman and Perry109 Also time series data are frequently non-stationary and vulnerable to random findings. Reference Lucey, Corcoran, Keeley, Brophy, Arensman and Perry109 Another source of bias is possible registration bias concerning suicides between countries and over time, and also concerning the quality of the economical statistics.

Finally, an important fundamental problem is that it is probably too early to arrive at conclusions concerning the impact of the current economic crisis on health, mental health and the suicide rate in particular. It seems necessary to wait until data up to at least 2020 are gathered in order to have a complete picture.

The authors chose to publish the full data-set their analysis was based on in an online table as they strongly believe that this database should be publicly available. One of the major obstacles of the current study was the difficulty of gathering statistical data from the various countries, although these data should had been easily accessible to every citizen. The authors believe that the publication of this data-set so that anyone can perform further analysis is one of the major contributions of the current study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.