The United States will be a majority–minority nation by 2043, and Latinos are already the largest minority group (United States Census 2012). Latino population growth has been especially pronounced in places where Blacks reside (Iceland Reference Iceland2009). Understanding how African AmericansFootnote 1 view the growing Latino population, and how this affects political behavior, is vital.

Scholars have alternately argued that shared social disadvantage causes or impedes political commonality between the two groups, in turn either fostering or hindering cooperation. Yet, most research relies on qualitative or observational data and has been unable to test whether there is a causal link, or specify the mechanism. Using survey experimentation on a national sample of African Americans, we test whether messages about social disadvantage promote a sense of shared political interests with Latinos.

We uncover null effects. Despite strong cross-sectional findings, there is not an immediate causal relationship between shared social disadvantage and African Americans’ relatively high political commonality with Latinos. Rather, the causal link between social inequality and cross-racial political commonality is more contingent and limited than previous research suggests.

COOPERATION OR CONFLICT?

Although by most measures Blacks are the most disadvantaged group in the United States, Latinos face economic, social, and political hurdles that result in similarly disadvantaged outcomes (Telles and Ortiz Reference Telles and Ortiz2008). Theories of political conflict and cooperation among minority groups rely on this shared social disadvantage. The competition framework posits that members of disadvantaged racial/ethnic groups are likely to see their interests as competing (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996, Olzak Reference Olzak1992); arguments for political cooperation assume that shared social disadvantage increases perceptions of commonality, leading to coalitions (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003). At the heart of this debate is whether Blacks’ disadvantaged social position will lead them to view Latinos as allies facing similar circumstances, or competitors for meager resources and power.

The existing empirical evidence is mixed. On the one hand, multiple studies find that Blacks and Latinos perceive that they are in competition with one another, leading to political conflict (Gay Reference Gay2006, Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2007, McClain and Karnig Reference McClain and Karnig1990, McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, DeFrancesco Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally, Scotto, Alan Kendrick, Lackey and Cotton2006, Sonenshein Reference Sonenshein, Browning, Marshall and Tabb2003). In many cities, rather than forming coalitions African Americans (Latinos) have defected from Democratic Latino (African American) candidates (Barreto Reference Barreto2004, Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003). However, among national elites there is little evidence of competition (Hero and Preuhs Reference Hero and Preuhs2013, Williams and Hannon Reference Williams and Hannon2016) and even findings of coalition building (Tyson Reference Tyson2016). At the mass level, while there may be “cracks in the rainbow,” there is still cross-racial electoral cooperation (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003). In sum, Blacks and Latinos have historically both cooperated and competed within the political realm, and both outcomes are thought to be driven by the groups’ shared social disadvantage relative to Whites.

POLITICAL COMMONALITY

Research on inter-minority political cooperation builds on linked fate—the sense that one's fate is connected to the fate of their racial group (Dawson Reference Dawson1994, Tate Reference Tate1993)—to connect perceptions of political commonality between communities of color with common (social) struggles (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003, McClain et al. Reference McClain, Carter, DeFrancesco Soto, Lyle, Grynaviski, Nunnally, Scotto, Alan Kendrick, Lackey and Cotton2006, Sanchez Reference Sanchez2008). Despite the prevalence of this logic in scholarship on inter-minority cooperation, we know of no studies that have tested whether perceptions of shared social disadvantage cause attitudes about inter-group political commonality. In part, the lack of causal research is due to the impossibility of randomizing social position. Previous research on this topic relies on creative analysis of observational data for theory-building and testing.

However, highlighting social inequality prior to measuring political commonality with Latinos should make social inequality more relevant to respondents’ calculations about commonality, as frames emphasize particular considerations to affect how individuals form preferences (Druckman Reference Druckman2011, Iyengar and Kinder Reference Iyengar and Kinder1987, Zaller Reference Zaller1992, Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). While we may not offer new information—the realities of racial disadvantage may be all too familiar— by varying how inequality is framed, we can test whether the theoretical causal link between social disadvantage and commonality holds. This paper provides the first rigorous test of this theoretical mechanism for the production of Black–Latino political commonality.

HYPOTHESES

Frames that emphasize shared Black–Latino inequality relative to Whites should promote political commonality with Latinos, compared to frames that emphasize comparisons between Blacks and Whites or Latinos and Whites, if the mechanism for building political commonality is a shared social disadvantage:

H1: Framing racial inequality as Black and Latino shared inequality compared to Whites should boost perceived commonality with Latinos.

Panethnicity and linked fate among Latinos can form a basis for commonality with African Americans (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003, Sanchez Reference Sanchez2008). We similarly expect racial linked fate will be correlated with perceptions of cross-racial political commonality:

H2: Linked fate should be positively associated with Latino commonality independent of treatments.

Most research assumes that social conditions translate into political beliefs about shared position and interests (Gay Reference Gay2006, Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2003). However, citizens are often unable to form political attitudes based on economic conditions, particularly when race is salient (Huckfeldt and Kohfield Reference Huckfeldt and Kohfeld1989, Key Reference Key1949, Roediger Reference Roediger1992). Respondents might require an explicitly political message to connect their shared social position to political commonality:

H3: Political messages should amplify the expected effects of racial frames.

DATA AND EXPERIMENTAL ANALYSIS

To test our hypotheses, we fielded a survey in Winter 2016 with 1,200 African Americans (Israel-Trummel and Schachter 2018).Footnote 2 Our sample was drawn from Survey Sampling International's (SSI) online panel and was quota sampled to meet current population survey (CPS) estimates for the Black population with respect to gender, age, education, and census region.

The experiment is a 4 × 2 × 2 design. First, respondents were randomized into one of the four groups. Three of the treatment groups received an abbreviated news article that varied how inequality was described: Blacks versus Whites, Latinos versus Whites, or Blacks and Latinos versus Whites (see the online Appendix for treatments). The fourth group received a placebo. This design is a form of an emphasis frame, where different dimensions of a political problem are emphasized, and each could potentially shape attitudes on the outcome variable (Druckman Reference Druckman2011). The second randomization decided whether the article focused on either housing or education. The final randomization offered a political message to half the respondents. Respondents who received the political treatment were told at the end of the article: “Experts predict that [the future of education reform/access to home loans] will depend on the results of the 2016 elections, with the Republican and Democratic parties expected to present competing proposals.” Following the treatment manipulations, respondents were asked about their perceptions of political commonality with Latinos.Footnote 3 Latino commonality ranges from 1 (Nothing in common) to 4 (A lot in common).

RESULTS

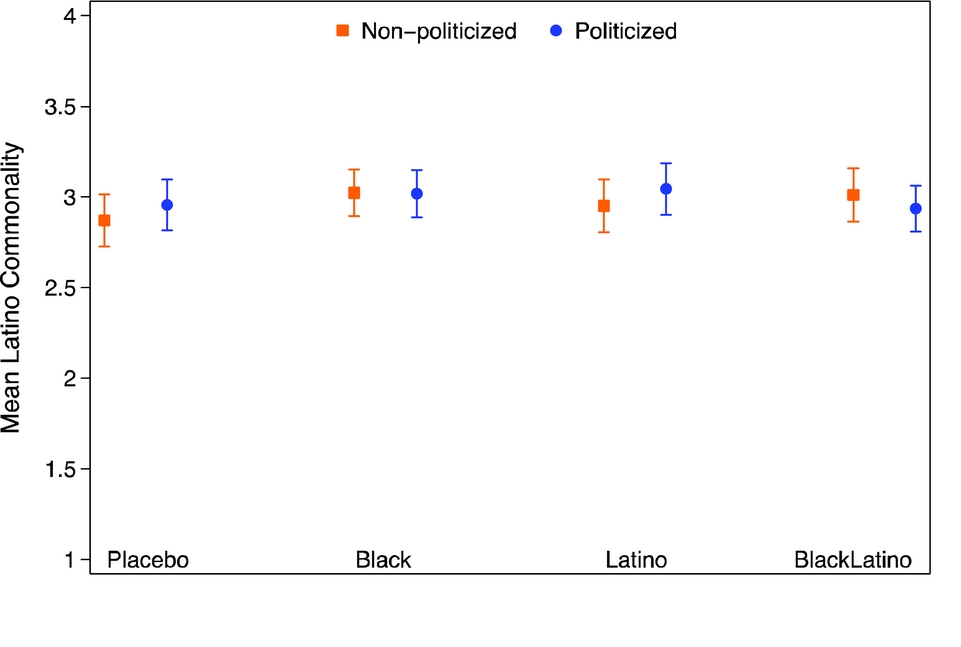

We first compare the main effects of the treatments relative to the placebo, pooling across the domain (housing or education). Figure 1 shows the lack of any significant differences. This is somewhat surprising as respondents in the Black–Latino condition received a specific message emphasizing shared Black–Latino social disadvantage. In the aggregate, it appears that framing social commonality fails to increase African Americans’ perceptions of political commonality with Latinos.Footnote 4 Adding further confidence to our null finding, in Table 1 we estimate the treatment effects on Latino commonality using OLS, controlling for respondent characteristics (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green2012). These models confirm our null findings.Footnote 5 The effect for each treatment is positive, but none reach statistical significance.

Figure 1 Treatment Effects on Latino Political Commonality.

Table 1 OLS Estimates of Treatment Effects on Latino Political Commonality, Coefficients and (SEs)

*p < 0.05.

†p < 0.10.

While the treatments have no main effect on political commonality with Latinos, it is possible that there are heterogeneous treatment effects. Given the relationship between linked fate and commonality, we test whether linked fate moderates the treatments. The lack of significant interaction between linked fate and the experimental treatments clarifies previous observational analysis. While African Americans with higher racial linked fate are more likely to express commonality with Latinos (H2), they are no more likely to respond to messages about shared inequality. Instead those who feel more linked to their own group are also more likely to believe their interests are similar to another minority group.Footnote 6

The analysis indicates that perceptions of shared social conditions are not the mechanism for building political commonality. Next, we test whether shared social position needs to be explicitly tied to politics. In brief, we find no support for the political mechanism within the educational domain, and limited evidence with housing.

Pooling across the inequality domains we find no difference comparing those who were told that experts expect the 2016 election to affect their issue versus those who did not receive a political message (Figure 2). Table 1 disaggregates the domains. These models confirm the null result for the pooled analysis and for education alone. However, within the housing domain, both Black–Latino conditions increase commonality (p = 0.066 political, p = 0.034 non-political), and the political Latino treatment boosts commonality relative to the non-political placebo (p = 0.047). Within the domain of housing access, providing information about Latino inequality relative to White, coupled with a political cue, can promote a sense of shared political interests with Latinos. In total, these results provide qualified support for H3. A political message, coupled with a racial frame about housing that references Latino inequality, promotes a sense of political commonality with Latinos. However, providing a political cue in the educational inequality domain does not affect Latino political commonality.

Figure 2 Political Messages and Treatment Effects on Latino Political Commonality.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Our results do not support the theory that shared social disadvantage is the causal mechanism for creating political commonality. There is no evidence that shared educational disadvantage promotes commonality, and very limited support for the mechanism within the domain of housing inequality, if shared disadvantage is coupled with a political message. We confirm the correlation between racial linked fate and Latino commonality, but our findings suggest that the mechanism of shared disadvantage (alone) between Blacks and Latinos is insufficient.

We are confident that we have identified a true null effect. Although pretreatment (in our case, real experiences of social disadvantage) is a threat to survey experiments (see Gaines, Kuklinski and Quirk Reference Gaines, Kuklinski and Quirk2007), individuals have multiple considerations that they could bring to bear on any issue; providing respondents with information emphasizing one of those considerations should encourage them to draw more heavily on that particular consideration (Zaller Reference Zaller1992, Zaller and Feldman Reference Zaller and Feldman1992). To test whether pretreatment could be limiting our results, we ran an additional survey of 178 Black respondents on MechanicalTurk in December 2017 comparing only the Black–Latino housing treatment versus the placebo. Although we find that there is high knowledge overall about inequality, treated respondents are significantly more likely to believe that Black and Latino borrowers tend to be given higher-priced mortgages than Whites (p = 0.03). Another measure of pretreatment (that Black and Latino borrowers tend to receive less coaching on mortgage borrowing) fails to achieve statistical difference between the treatment and placebo, but is in the correct direction (p = 0.16). Finally, we offer another true statement (whether Black and Latino borrowers are more likely to own homes in disadvantaged neighborhoods compared to Whites) that was not mentioned in the treatment article. We find no difference between beliefs about the accuracy of this statement comparing placebo and treatment conditions on this measure (p = 0.45), suggesting that our treatments did move beliefs about inequality as described in the article, and pretreatment cannot fully account for our null results. In addition, if pretreatment were driving our results, we would expect Blacks living in areas with low-exposure to Latinos (e.g., lower percent Latino zip-codes and low-immigration states) to demonstrate stronger treatment effects relative to those with more exposure (and thus more pretreatment). However, we find no differences in treatment effects by exposure to Latinos. Finally, while pretreatment is always a concern, research on Whites shows that race can be framed and primed despite the historic, institutional, and structural realities of race (Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2001, Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Hutchings and White2002). Researchers should not simply assume that race cannot be experimentally tested on minority samples.

Our results indicate that a commonly assumed mechanism for building cross-racial minority cooperation is likely insufficient. Scholars need to theorize what other mechanisms could be driving group commonality. We hope that our findings will spur further causal research on minority political behavior. As the United States marches closer to majority–minority status, understanding the forces that shape inter-minority politics will only increase in importance.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2018.15