Introduction

High-quality evidence demonstrates the efficacy of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) in patients with autoimmune or inflammatory neuromuscular disorders. Reference Patwa, Chaudhry, Katzberg, Rae-Grant and So1,Reference Perez, Orange and Bonilla2 Synthesized from pooled human plasma obtained from a large number of healthy donors, the main component of IVIG is intact Immunoglobulin G (IgG) molecules and is marketed for intravenous (IV) infusions. Reference Barahona Afonso and João3 Several immunomodulatory mechanisms for IVIG including actions on B and T cells, macrophages, complement, and cytokines have been proposed. Reference Jacob and Rajabally4 The treatment of chronic neuromuscular disorders such as chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP) and myasthenia gravis (MG) require long-term immunomodulatory maintenance therapy. However, despite being efficacious, there are several practical limitations that make long-term IVIG maintenance less attractive both from the patient and health care delivery perspective. In this regard, subcutaneous immunoglobulin (SCIG) has several advantages over IVIG. Although most data are on primary immunodeficiency syndromes, recent meta-analysis and the results of the PATH study which was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial have shown SCIG to be as efficacious as IVIG with a significantly better safety profile in CIDP, and similar outcomes have been noted with multifocal motor neuropathy with conduction block and MG. Reference Alcantara, Sarpong, Barnett, Katzberg and Bril5–Reference van Schaik, Bril and van Geloven10 Based on these evidence, SCIG has been approved for the maintenance treatment for CIDP. In this review, we discuss the practical aspects of transitioning a neuromuscular patient from IVIG to SCIG therapy. We also highlight the workflow in our unit, which is essential for a smooth and seamless transition from IVIG to SCIG.

Difference in Formulations and Pharmacokinetics between IVIG and SCIG

IVIG is available as 50 mg/ml (5%) or 100 mg/ml (10%) formulations, while SCIG is available currently in 10% and 20% concentrations stabilized with L-proline. Generally, the IV and subcutaneous formulations cannot be interchanged though there are exceptions with certain brands. After IVIG infusion, there is an initial rapid rise in the first day followed by decline of immunoglobulin (Ig) levels over the first 3 days to 50%, and further slow decline with a half-life of around 22 days. With IVIG therapy, there is a significant fluctuation of serum Ig levels, and a wearing-off effect prior to the next infusion is reported by many patients. Reference Salameh, Deeb, Burawski, Wright and Souayah8,Reference Rojavin, Hubsch and Lawo11 SCIG, on the other hand, is characterized by a slow, steady absorption from the subcutaneous space and the lymphatic system, producing lower peak levels, but higher trough levels and a steady serum concentration without the major fluctuations in serum Ig levels observed with IV administration.

Advantages and Disadvantages of SCIG over IVIG

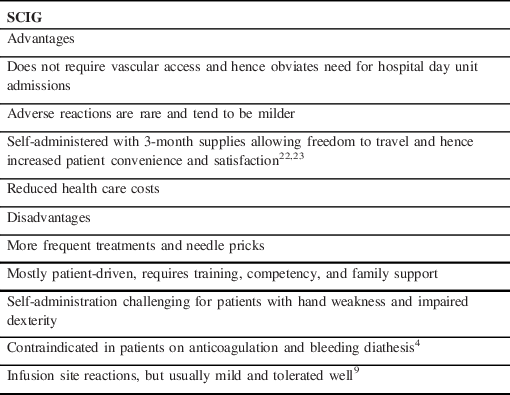

The rapid rise of serum Igs, increased serum viscosity, and complement activation are suspected to be responsible for most of the side effects of IVIG. Reference Jacob and Rajabally4 With a lower rate of increase, reduced peak serum levels and a steady state, SCIG has significantly lower risk of adverse reactions. Reference Salameh, Deeb, Burawski, Wright and Souayah8,Reference Geng, Piracha, Rashid and Rigas12–Reference Markvardsen, Sindrup and Christiansen14 Moreover, a typical maintenance dosage of IVIG consists of 1g/kg every 3 to 4 weeks infused over 6 to 8 h in a hospital day unit, while in the case of SCIG administration amounts to one or two infusions per week averaging 1.5 h per infusion at the patient’s convenience. During SCIG infusion, the patient can continue with their other activities and this route affords much greater flexibility. Reference Rasutis, Katzberg and Bril15 Although the cost of SCIG may be slightly higher than IVIG, budget impact models show that the overall health care system cost with SCIG is significantly lower due to fewer hospital visits and shorter nursing time required for infusion. Reference Martin, Lavoie, Goetghebeur and Schellenberg16,Reference Vaughan17 Equally importantly, several studies show improved patient satisfaction and quality of life on switching from IVIG to SCIG and SCIG scored better when compared to home-based IVIG as well. Reference Bienvenu, Cozon and Hoarau18–Reference Cocito, Peci and Lauria Pinter20 Table 1 summarizes some of the main advantages and disadvantages of SCIG.

Table 1: Summary of the main advantages and disadvantages of SCIG over IVIG

SCIG = subcutaneous immunoglobulin.

Selecting the Patient

SCIG is a treatment option for any patient with a neuromuscular disorder for whom IVIG maintenance treatment is indicated. Although there is some evidence for its direct use in mild to moderate exacerbations in MG and also for as first-line therapy in treatment naïve patients with CIDP, the evidence for initial SCIG in acute situations is limited, and considering its pharmacokinetic profile, we suggest IVIG be used first in most situations. Reference Beecher, Anderson and Siddiqi21,Reference Markvardsen, Sindrup and Christiansen14 We seldom initiate a patient on SCIG and offer transition to SCIG in those patients who respond well to IVIG and are stable on Ig therapy, and for those on IVIG with intolerable side effects or wearing-off with symptoms re-emerging before the next dose. It is necessary to counsel the patient about the advantages and disadvantages of SCIG, and this therapy is better offered to patients who are comfortable with handling the instructions for self-infusion, who are keen for autonomy, and who do not have a needle phobia. Since anticoagulation and bleeding diathesis are contraindications to SCIG, patients with these conditions are not selected for this therapy.

Patient Counseling

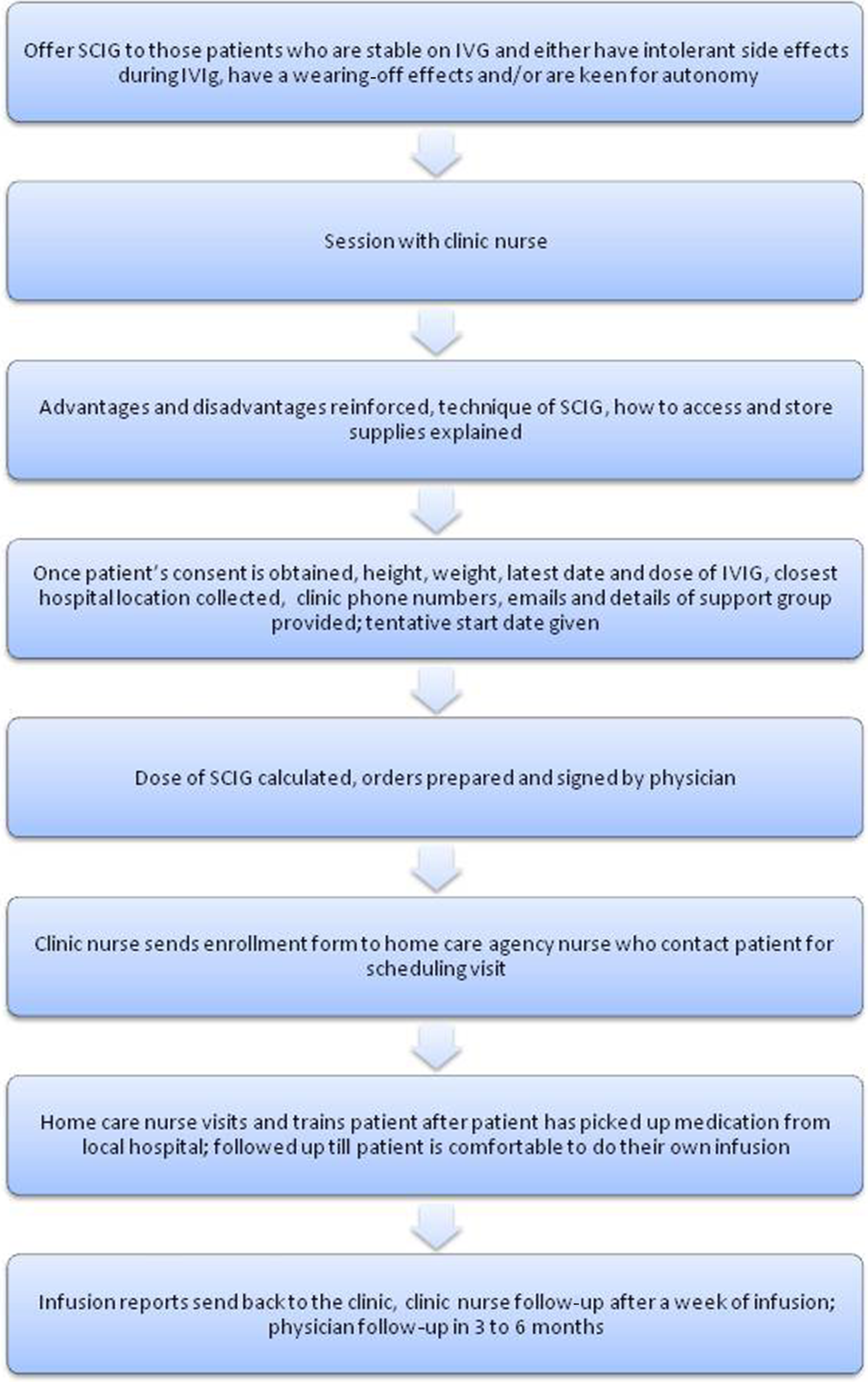

In-depth patient counseling is vital for compliance. Patients should have clear explanations about the reasons, advantages and disadvantages of transitioning, where it can be done, how long it takes, where and how to inject, how to procure the supplies, people involved in treatment, and contact numbers and emails for support to respond to any concerns that arise. Figure 1 shows the workflow in our unit for transferring a patient from IVIG to SCIG.

Figure 1: Flow chart depicting the workflow in our clinic in transitioning a patient from IVIG to SCIG.

Dose Calculation

Most of the data on pharmacokinetics and dose conversions involving SCIG are from studies in primary immunodeficiency diseases, and recommendations have been extrapolated for neurological indications. The differences in the pharmacokinetics mean that at equivalent doses, the peak serum IgG levels after weekly SCIG are 31% lower and the trough levels are 10%–20% higher compared to monthly IVIG, while the bioavailability calculated by the area under the serum concentration–time curve (area under curve, AUC) is lower. Reference Cocito, Peci and Lauria Pinter20,Reference Beecher, Anderson and Siddiqi21 Based on pharmacokinetic studies, to ensure non-inferiority as far as the bioavailability was concerned, a mean dose adjustment of 137% to 153% of the IVIG doses was recommended for different 20% SCIG formulations. Reference Cocito, Peci and Lauria Pinter20,Reference Berger, Rojavin, Kiessling and Zenker22,Reference Wasserman, Melamed and Nelson23 Subsequently, the US prescribing authorities recommended that patients switching from IVIG to 20% SCIG are treated with at least 1.37 times their previous IVIG dose. Reference Berger and Ochs24 On the other hand, clinical trials from Europe have based their comparisons of efficacy on the IgG trough levels. Since, even with an equivalent dose conversion, the IgG trough levels are higher with SCIG, the European recommendations are for a 1:1 dose adjustment when switching from IVIG to 20% SCIG. Reference Krishnarajah, Lehmann and Ellman25–Reference Gardulf, Nicolay and Asensio27 The Canadian Blood Services also recommend an equivalent dose switch followed by titration to achieve an IgG trough level of at least the lower limit of the age-specific serum IgG reference range, or as needed to achieve clinical effectiveness. Reference Fadeyi and Tran28 Several trials in primary immunodeficiency found comparable results between the two dose adjustment methods, but there were certain factors such as reduced rate of missed work or school days and length of hospital stay caused by infection that were found to favor the higher conversion coefficient. Reference Gardulf, Nicolay and Asensio27,29,Reference Haddad, Berger, Wang, Jones, Bexon and Baggish30 From the neurological perspective, it remains uncertain whether the treatment response depends on the IgG trough or peak levels or the total bioavailability and which pharmacokinetic parameter determines the treatment response. In the PATH extension study, a higher dose of SCIG was associated with lesser relapse of CIDP. To protect against underdosing, especially during the initial switch from IVIG to SCIG, we adjust the dose by a factor (DAF) of 1.37, and further adjustments are made based on the clinical response.

The weekly dose of SCIG in grams is therefore calculated with the following formula:

Weekly dose of SCIG (g) = Maintenance dose of IVIG (g) x DAF/number of weeks between IVIG doses. Then, the calculated dose in grams is multiplied by a factor of 5 for 20% SCIG formulations or by 6.25 for 16% formulations giving the total volume of SCIG in milliliters to be infused in 1 week. This can be divided into 2 or 3 doses per week. In the few patients who may be receiving 2 g/kg of IVIG every 3 or 4 weeks as maintenance therapy, a 1:1 replacement is suggested, since higher SCIG doses raise concerns about increased dose-related side effects. IgG levels are used by certain centers to guide further dose adjustments, but the reliability of these levels in any given patient is open to question, and we suggest using the patient’s clinical status when deciding on further dose modifications. Reference Orange, Belohradsky and Berger31,Reference Bonilla32 On rare occasions when a patient is directly initiated on SCIG, the dose is calculated after determining the dose of IVIG required based on the patient’s ideal body weight.

Supplies Needed for SCIG Infusion

Supplies for SCIG infusion include a mechanical infusion pump; needle administration sets (6–12 mm size), and dispensing pins/needles for extracting SCIG; an infusion rate regulator, which enables the patient to use a dial to regulate flow rate; a 60-ml syringe; a dispensing pin (spike); occlusive dressing or tape; alcohol swabs; immunoglobulin vials; a sharps container; and a patient diary or logbook (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3).

Table 2: Components of the SCIG infusion system

SCIG = subcutaneous immunoglobulin; mm = millimeters.

Figure 2: Components of the subcutaneous infusion system: (A) vial containing SCIG, (B) spike used to draw SCIG into the syringe from the vial, (C) ambulatory infusion pump, (D) 60-ml syringe with the spike attached to draw SCIG from the vial, (E) flow rate controllers, (F) ambulatory infusion pump with a syringe attached, (G) infusion tubing with multi-needle set (H) magnified view of the 6-mm subcutaneous needle, (I) occlusive dressing, and (J) sharp container.

Figure 3: SCIG infusion system. (A) vial containing SCIG, (B) spike used to draw SCIG from vial into the syringe, (C) syringe with spike attached, (D) infusion pump with a syringe attached, (E) flow controller attached to the syringe at one end and tubing at the other, (F) tubing with the multi-needle unit, (G) occlusive adhesive dressings.

Technique of Infusion

The SCIG dose is initiated 1 week after the last dose of IVIG. The site of infusion can be abdomen, thighs, lower back, or upper arms, and most patients prefer the abdomen or thighs. (Figure 4) Multiple sites can be infused simultaneously if needed, but the sites should be at least 2 inches apart. The desired amount of SCIG is drawn into the 60-ml syringe and is fixed into the infusion pump, connected to the regulator, tubing, and the subcutaneous needle. The needle is selected based on the thickness of the subcutaneous fat and ranges from 6 to 12 mm, much smaller than IV needles. After the site is cleaned thoroughly with an alcohol swab, the skin with the subcutaneous fat is pinched with one hand and the needle inserted with the other and fixed in place with an occlusive dressing. The regulator can then be set for a rate of infusion which can be started at about 20 ml/h and later increased to 25–30 ml/h. The optimal volume of 20–30 ml per site, but this can be increased gradually up to 40–50 ml depending on patient tolerance. In general, for a smooth and successful transition, a gradual escalation in dose and number of sites is advised. The patient is advised to note the details of the infusion in the logbook, including any adverse reactions. After the infusion, the pump is cleaned and stored, and the needles and tubing discarded in a suitable sharps container.

Figure 4: Diagram depicting the ideal sites for needle placement for SCIG infusion.

Home Care Nursing Support Program

Each manufacturer of SCIG has established a home support program providing nursing services for this therapy. Once the distributer’s nursing support group receives the enrollment forms, they contact the patient to schedule a home visit which is made after confirming that patient has all the necessary supplies. The components for the infusion system are dispatched by the respective manufacturer to the patient’s address, while the SCIG is collected by the patient or caregiver from their closest blood bank, to which the dose and orders for SCIG have been put in by the clinic nurse. The clinic nurse coordinates the visit and contacts both the patient and the home visit nurse. During the visit, the home care nurse trains the patient or care giver on how to prepare the infusion, choose the infusion site, insert and fix the needle, discard the sharps, and maintain the logbook. Generally, four sessions of training and infusion will be supervised by the home visit nurse unless the patient desires further sessions. SCIG is always ordered by the clinic nurse for the patient to pick up from their local hospital blood bank. The home nurse sends infusion reports to the clinic and does follow-up visits with the patient at regular intervals. In those clinical settings where the services of a dedicated clinic nurse are not available, the physician introduces the transition, performs the dose calculation of SCIG, orders at the most convenient blood bank for the patient, and introduces the home support program to the patient. The home support program nurse then fully trains the patient and also may order further SCIG doses, depending on the specific SCIG.

Potential Adverse Effects and Comparison with IVIG

The adverse effects with immunoglobulin treatment can be immediate such as flu-like symptoms (80%), dermatological (6%), and rarely hypotension and transfusion associated lung injury; or delayed which include thrombotic events such as stroke or myocardial infarction (MI) (1%), aseptic meningitis (0.6%–1%), hemolysis (1.6%), and rarely renal dysfunction. Reference Guo, Tian, Wang and Xiao33 The different pharmacokinetic properties and the slow rate of absorption mean that the chances of these systemic adverse effects are significantly lower with SCIG. The meta-analysis comparing IVIG and SCIG in patients with primary immunodeficiencies clearly showed a better safety profile for SCIG with an odds ratio of adverse effects of 0.5 compared to IVIG. Reference Bonilla32 Another meta-analysis comparing these two agents in inflammatory neuropathies found a relative risk reduction by 28% in moderate and/ or systemic adverse effects with SCIG. Reference Racosta, Sposato and Kimpinski6 The frequency of adverse effects in the SCIG group in neuropathies was 5% and might be slightly higher compared to other patient populations with reported rates of 0%–3%, since the dose of SCIG tends to be higher for chronic neuropathies. Reference Racosta, Sposato and Kimpinski6 The most common adverse effects of SCIG are local infusion site reactions which include itching, burning sensation, leakage from the infusion site, and mild redness and/ or swelling which usually subsides over 12 to 24 h. There is a wide range in the reported incidence of local adverse reactions from 0.003 events /infusion to 0.58 events /infusion, and this variability may be related to differences in reporting and recording. Reference Shabaninejad, Asgharzadeh, Rezaei and Rezapoor34,Reference Ballow, Wasserman, Jolles, Chapel, Berger and Misbah35 The intensity of local reactions tends to subside with subsequent infusions and seldom leads to discontinuation of treatment. Starting with low volumes and a slow infusion rate with gradual escalation, use of appropriate size needles and the use of ice packs after infusions can help to relieve the majority of local reactions. Reference Guo, Tian, Wang and Xiao33

Transitioning Back to IVIG

In general, few patients request return to IVIG after having been on SCIG. Patients’ attitudes and personality traits can also influence this decision. 36,Reference Kittner, Grimbacher, Wulff, Jäger and Schmidt37 Younger people who are actively employed and desire flexibility in their life style and who are more stable and self-confident and less susceptible to psychological stress prefer SCIG. Reference Kittner, Grimbacher, Wulff, Jäger and Schmidt37 Some patients find the increased treatment frequency and responsibility of self-treatment to be overwhelming and request switching to IVIG therapy. Reference Rasutis, Katzberg and Bril15 A lack of information about the benefits, misconceptions about the technical demands of self-infusions, and a paradoxical perception of “lack of freedom” could be other considerations. Despite being on SCIG for 12 months, about 20%–30% of patients do not show a clear preference for SCIG. Reference Jiang, Torgerson and Ayars38,39 Some other reasons for returning to IVIG include clinical worsening or perceived lack of benefit on switching from IVIG to SCIG and infusion site reactions. While there is no data on the dosage regimen for switching back to IVIG, a logical recommendation would be to return to the previous dose of IVIG followed by further titration based on clinical response.

Future Trends

The volume of SCIG that can be infused at a single site is a limiting factor which necessitates frequent infusions or the use of multiple needle punctures and infusion sites. Use of recombinant human hyaluronidase (rHuPH20) with 10% SCIG – also called facilitated SCIG (fSCIG) – may help overcome the volume issue as this form of SCIG breaks down the subcutaneous extracellular matrix and facilitates absorption and thus allows infusions of larger volumes and better bioavailability. This affords infusion volumes of up to 600 ml with rates of infusion titrated up to 240 ml/h. This therapy has been approved for primary immunodeficiency diseases, and a phase III randomized controlled study is underway to examine the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of fSCIG in patients with CIDP. 36

Conclusion

Transitioning patients from IVIG to SCIG offers several advantages in terms of fewer side effects, better quality of life, increased patient independence, and lower health care costs. Therefore, it is generally advantageous for multiple stakeholders to switch patients from IVIG to SCIG. Appropriate patient selection, fulsome patient counseling, and a collective effort between the physician, clinic nurse, and home visit nurse all ensure a smooth and successful transition from IVIG to SCIG.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Authorship

DM was involved in reviewing literature and drafting and editing the manuscript; ES was involved in review of literature and editing the manuscript; and VB was involved in concept and design, critically revising, and final approval of manuscript.