Recent excavations at the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B mega-site of Motza (7600–6000 BC), central Israel, have revealed a rare human burial with two foxes. The fox bones were dismembered, except for one foot found in articulation, and scattered among the human remains. What could this burial reveal about interactions between humans and small carnivores in the eighth and seventh millennia BC? We propose that Neolithisation entails closer relations between humans and small carnivores, relations that find expression in ritual practice. This is an animistic reflection of an anthropogenic ecology, which is advantageous to such animals and can be related to the general transition to agriculture in the Levant during this period.

Motza, located in the Judean Hills west of Jerusalem, is one of the largest sites in the southern Levant, approximately 40ha (Figure 1). It was previously excavated (Khalaily et al. Reference Khalaily2007) and is remarkable for its architecture, plaster floors, a lithic assemblage rich in arrowheads, multiple graves and numerous animal bones. As one of the earliest and largest agricultural villages in the Mediterranean phytogeographic zone, Motza has much to contribute to our understanding of the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture, and its economic, ecological, and social implications. We focus on a double burial of an adolescent and an adult with dismembered fox carcasses; we argue that this is important evidence of symbolism in the Neolithic and how it is reflected in the human-modified environments of the period.

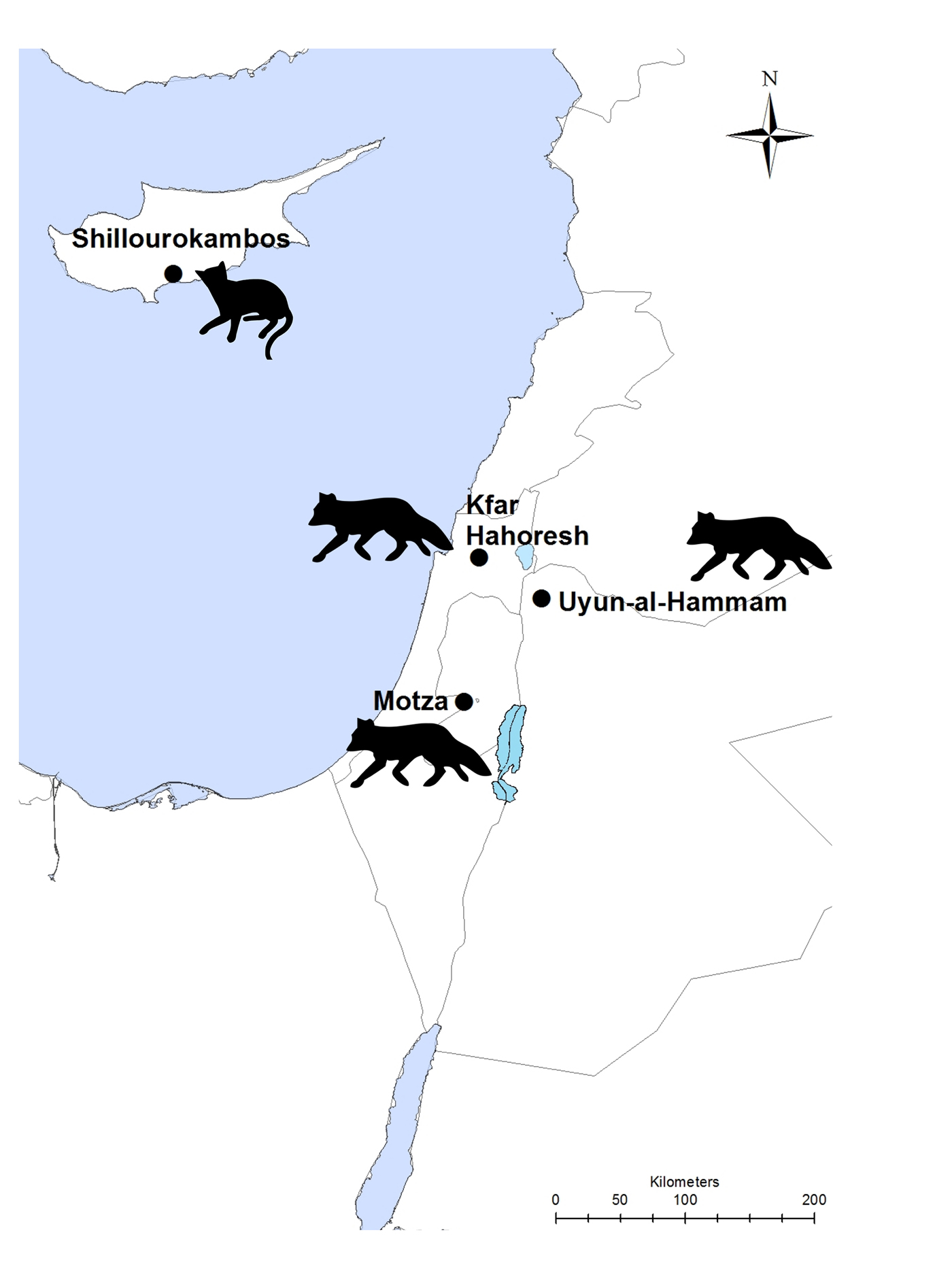

Figure 1. Map showing sites mentioned in the text. Base map: Flanders Marine Institute (2019) (available at: www.marineregions.org) (CC-licence).

Human burials with small carnivores (excluding domestic dogs) are known from a few sites (Davis & Valla Reference Davis and Valla1978; Tchernov & Valla Reference Tchernov and Valla1997) (Figure 1). At the pre-Natufian site (15 250–12 200 cal BC) of Uyun-al-Hammam, Jordan, a partly articulated fox skeleton was found in a human burial (Maher et al. Reference Maher, Stock, Finney, Heywood, Miracle and Banning2011; Goring-Morris & Belfer-Cohen Reference Goring-Morris, Belfer-Cohen and Hodder2013). Fox teeth and mandibles are often found in Natufian burials (Davis & Valla Reference Davis and Valla1978; Tchernov & Valla Reference Tchernov and Valla1997; Goring-Morris Reference Goring-Morris and Clark2005; Goring-Morris & Belfer-Cohen Reference Goring-Morris, Belfer-Cohen and Hodder2013). At the Pre-Pottery Neolithic site of Shillourokambos, Cyprus (7500–7200 cal BC), an articulated cat skeleton was discovered in a human burial (Vigne et al. Reference Vigne, Guilaine, Debue, Haye and Gérard2004; Le Mort et al. Reference Le Mort, Vigne, Davis, Guilaine and Brun2008). During the Neolithic, fox bones associated with human burials are known from the nearby Early Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site of Motza, where the burial of an adolescent associated with a fox mandible was excavated (H. Khalaily pers. comm.). At the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B ritual site of Kfar Hahoresh, human skulls were found with numerous fox mandibles, and partly articulated fox bones were excavated from two child burials (Horwitz & Goring-Morris Reference Horwitz and Goring-Morris2004; Goring-Morris Reference Goring-Morris and Clark2005; Meier et al. Reference Meier, Goring-Morris and Munro2017). Small carnivores, especially foxes, are associated with human burials before the Neolithic, and seem to have been symbolic.

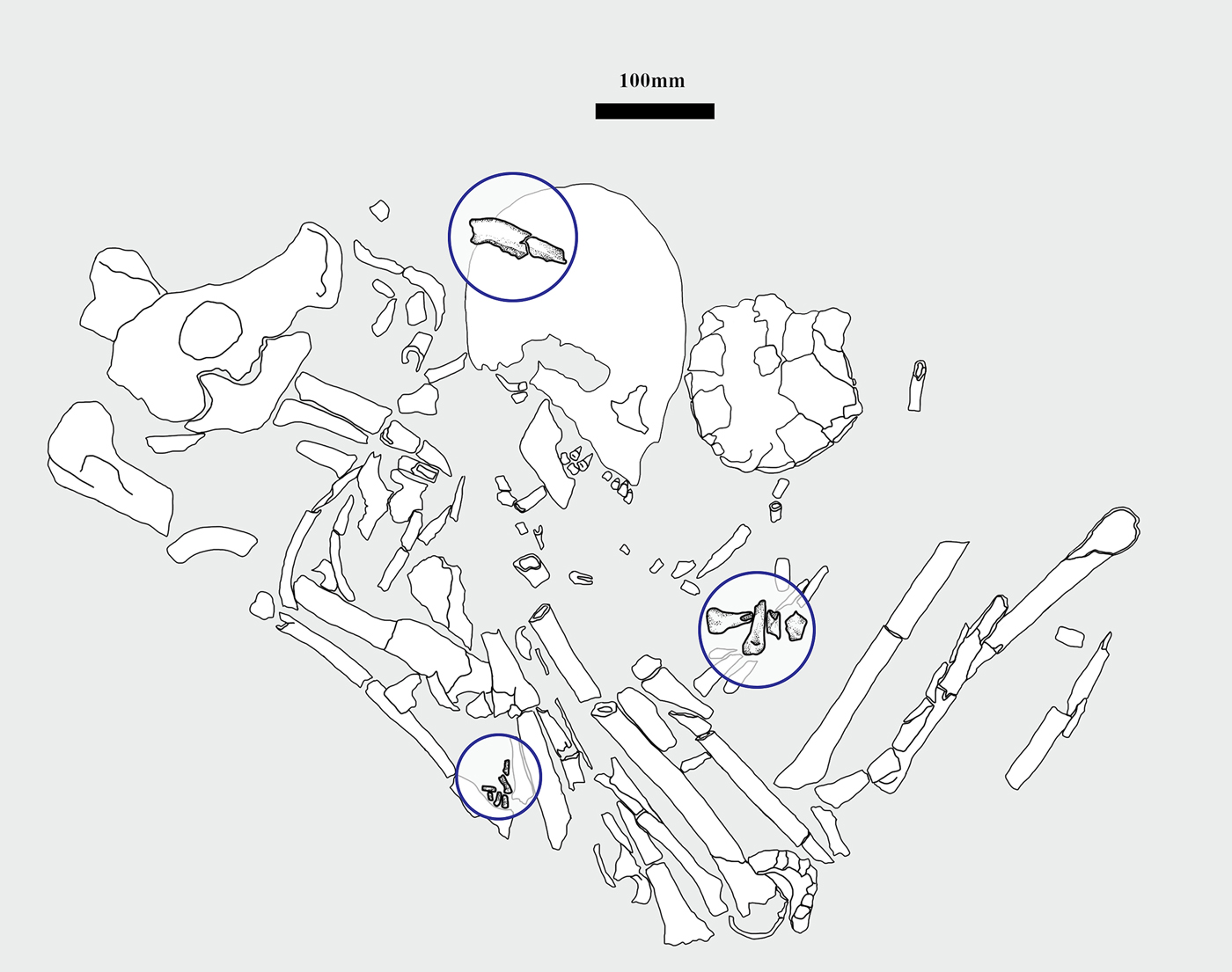

The recently discovered Motza burial (Figures 2–3), found in area B at the site (Figure 4), is close to a wall and remnants of a plaster floor, suggesting a domestic context. The earliest burial in the pit is that of a child; it seems to have been disturbed by the double inhumation of an adult male (over 60 years old) and an unsexed adolescent. The adult skeleton was disarticulated and appears to have been interred in a rectangular container, which has not survived. This may indicate reburial at the same time as the adolescent, who was interred above the adult, lying on his right side in a flexed position.

Figure 2. Photograph of the burial, courtesy of Lauren Davis, Israel Antiquities Authority.

Figure 3. Illustration of the burial with fox elements outlined in blue. Drawing by Aya Marck.

Figure 4. Site plan; area B is outlined in bold black; the location of the burial is marked in red. Plan drawn by Doaa Salman, used with permission of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

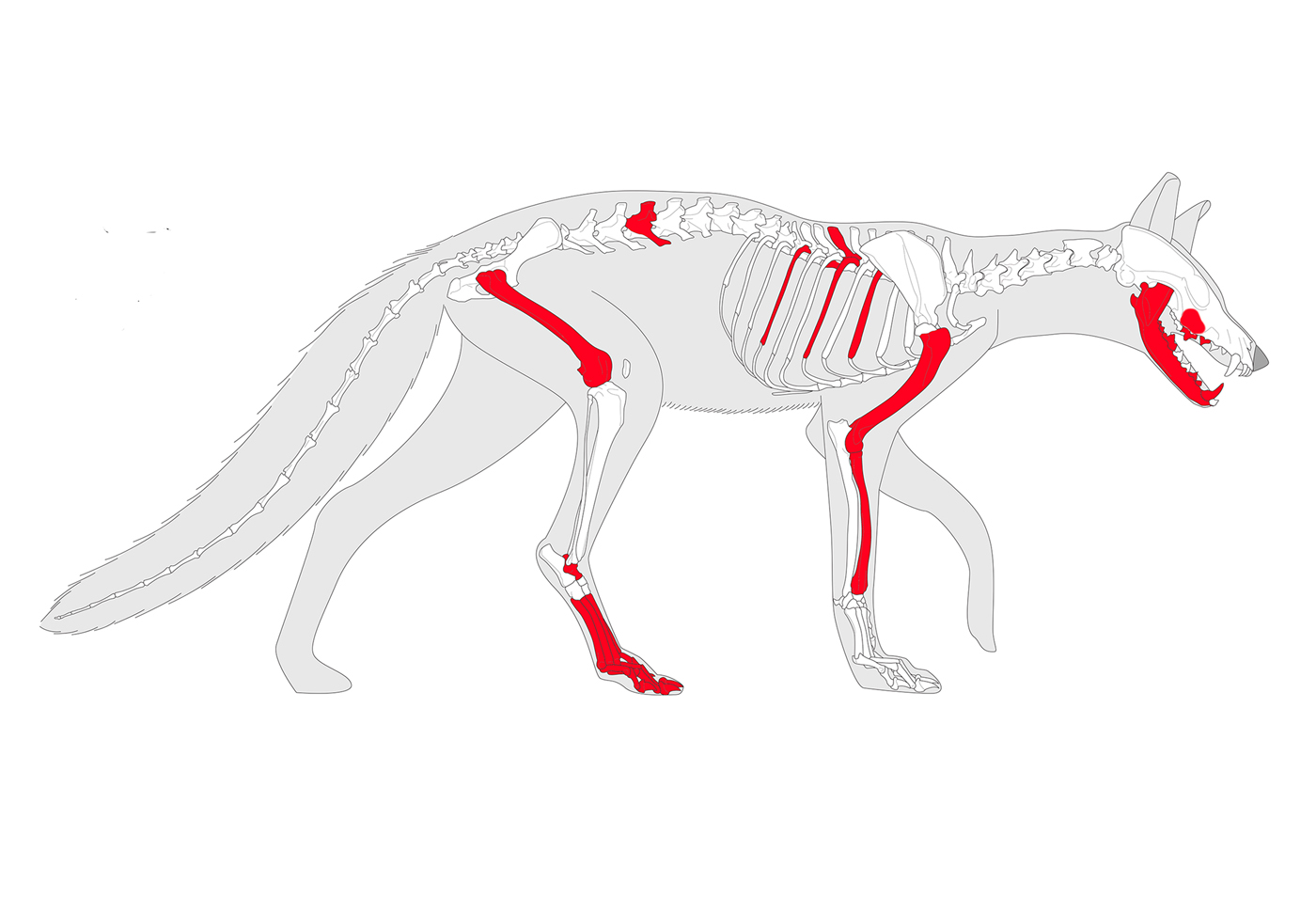

The location of fox bones in the grave (number of identified specimens—43; minimum number of individuals—2) associates them clearly with the later double burial and is quite distinct from caprine bone fragments occurring as unstructured finds in the grave backfill. A left mandible lay on the skull of the adolescent; two right femurs and two right mandibles were positioned on the right forearm. Fox phalanges, metapodials and a fully articulated astragalus of a right leg were placed inside the funerary container of the adult under his right femur. A fox humerus and radius were also placed in the burial (Figure 5). Taphonomic processes and compaction probably account for the way that the fox remains were scattered in the burial; their original arrangement is unclear. Other finds associated with the interment include beads, shells, worked stone and a stone bracelet.

Figure 5. Skeleton of a fox with the elements found in the burial coloured red. Drawn by Michel Coutureau and Céline Bemilli and taken from ArcheoZoo.org (available at: https://bit.ly/2mLcsbV).

Human burials with animals dating to the transition from hunting and gathering to farming are particularly important in understanding shifting relations between humans and animals at this time (Horwitz & Goring-Morris Reference Horwitz and Goring-Morris2004; Vigne et al. Reference Vigne, Guilaine, Debue, Haye and Gérard2004; Grosman et al. Reference Grosman, Munro and Belfer-Cohen2008; Maher et al. Reference Maher, Stock, Finney, Heywood, Miracle and Banning2011; Meier et al. Reference Meier, Goring-Morris and Munro2017). The move to permanent settlements had a dramatic effect on the immediate environment. Prolonged occupation of sites created increasing amounts of refuse and anthropogenic ecologies, which in turn attracted animals, including small carnivores such as foxes. A commensal relationship formed between these animals and humans (Zeder Reference Zeder2012), augmenting the role of foxes in Neolithic culture and society (Peters & Schmidt Reference Peters and Schmidt2004; Yeshurun et al. Reference Yeshurun, Bar-Oz and Weinstein-Evron2009).

Burials with small carnivores attest to their ecologically driven increased visibility; more implicitly, they demonstrate symbolism responding to shifts in proximate animal communities. Symbolic incorporation of elements of the animal world in ritual contexts is typical of animistic, not theistic, religions (Rappaport Reference Rappaport1979; Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999; Russell Reference Russell2011).

This liminal phenomenon of an agricultural society retaining hunter-gatherer ritual practices, and perhaps ideologies, is clearly revealed in human burials with animals. Retention of these practices supports a mosaic process of Neolithisation, in which symbolism continues to render the natural world surrounding agricultural societies as intelligible and meaningful.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Israel Antiquities Authority for permitting publication of data from the Motza excavation. We are grateful for the ERC Starting Grant 802752 (awarded to N. Marom). We also wish to thank Aya Marck, Adva Peretz and Doaa Salman for graphic editing and designs.