Introduction

For parents caring for a child living with a life-limiting diagnosis, a supportive, therapeutic, and satisfying relationship with their health-care team is highly dependent on the quality of communication from clinicians (Ciriello et al. Reference Ciriello, Dizon and October2018; Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Bradford and Herbert2015; Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Snaman, Johnson, Wolfe, Jones and Kreicbergs2018; Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018). However, a considerable body of literature suggests parents are often dissatisfied with the standard of communication they receive from health-care providers (Brouwer et al. Reference Brouwer, Maeckelberghe and van der Heide2021). Parents have called for a focus on research that explores best practices for communication that will enable clinicians to be equipped with the tools to support “safe and candid” communication (Lord Reference Lord2019).

Current studies in pediatric palliative care reveal parents value good communication with their child’s clinicians second only to pain and symptom control as a priority need (Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018). When asked, parents nominate they want information to be delivered in a way that enables them to trust what they are being told (Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018). Parents also seek to be involved in shared decision-making about their child’s care, with an onus on the clinician to establish effective communication and shared understanding in order to achieve this (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Snaman, Johnson, Wolfe, Jones and Kreicbergs2018; Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018).

Clinicians tend to overestimate their own aptitude when it comes to communication (Ciriello et al. Reference Ciriello, Dizon and October2018). Expressions used in clinical communication are often vague and open to multiple interpretations, and yet there may be an implicit assumption by clinicians that patient and professional understand one another (Ohnishi et al. Reference Ohnishi, Fukui and Matsui2002). Adding to this, clinicians may find it difficult to discuss topics such as poor prognosis, death, and dying, and report feeling inexperienced and uncomfortable when doing so (Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Bradford and Herbert2015; Marsac et al. Reference Marsac, Kindler and Weiss2018). This is not surprising given that communication training in topics relevant to palliative care is generally lacking for health-care students (Cowfer et al. Reference Cowfer, McGrath and Trowbridge2020). Clinicians, like many across society, find these topics challenging to discuss (Fallowfield et al. Reference Fallowfield, Jenkins and Farewell2002).

A paucity of studies describe, from the parent’s perspective, the acceptability of approaches to serious illness conversations and the impact of a clinician’s chosen language on the quality of communication. While we suspect that language is central to communication and human connection (Alex and Whitty-Rogers Reference Alex and Whitty-Rogers2012; Cherny et al. Reference Cherny, de Vries and Emanuel2014; Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018), the literature would suggest clinician and parent may not yet align on what specifically constitutes high-quality communication (Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Bradford and Herbert2015). There is a role therefore to research what specific approaches may optimize serious illness communication in this difficult setting of care.

Methods

Study design

This study employed a prospective exploratory qualitative design and was approved on 15 September 2020 by The Human Research Ethics Committee of The Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia (HREC/60837/RCHM-2020). Study findings were reported against the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) framework (Tong et al. Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig2007).

Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)

Two PPI representatives – parents of a child with a life-limiting condition registered with the statewide pediatric hospice – provided input into the study design and interview schedule at the study outset which supported the process of obtaining institutional ethical approval.

Participants

Participants were English-speaking adults (>18 years) who were the parent of a child (aged 4 months–18 years) diagnosed with a condition known to be life-limiting and known to the outpatient services of the Neurodevelopment and Disability (NDD) Department at the major tertiary Children’s Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. Participants were purposively sampled to achieve a broad representation of relevant clinical and sociodemographic factors. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

A clinical nurse consultant (IS) routinely involved in the family’s care approached eligible families to seek consent for the researcher (NM) to contact the parent, discuss the study, and invite participation. Parents who consented were then subsequently interviewed by a videoconference call due to COVID-19. In-depth exploratory interviews of 60–90 minutes duration were conducted by 1 researcher (NM, a pediatric palliative care doctor exclusively involved with the NDD Department in a research capacity who had never met either the parents or their children previously). Interviews were held online from November 2020 to June 2021 with the use of encrypted videoconference software.

An interview schedule provided a guide to structure the discussion. Relevant demographic data were self-reported by participants including the child’s diagnosis, age, and health-care teams involved. The interview began with a probing question which prompted recollection of a clinical interaction or conversation with a clinician the parent remembered and invited open reflection. Parents were then presented with 2 specific hypothetical vignettes which simulated a clinician talking to a parent on the topics of “prognosis and hope” and “future wishes and goals of care.” These vignettes were designed to encourage reflection on the acceptability of the language and approach used. Direct probes were used to elicit views on the impact of the approach and whether a different one would have been more acceptable.

All interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim with the assistance of transcription software Otter.ai. Data were checked and corrected by the researcher (NM) before analysis.

Data analysis

A thematic analysis in line with Braun and Clark was conducted, with themes inductively derived and data coded for its semantic and latent meaning (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2022). Immersion in data by the principal investigator was achieved through direct and active participation in the interviews, and thereafter during ensuing analysis and interpretation of the data. Each transcript was first read in full for familiarization, then coded for key concepts relevant to the research aim, allowing for the development of preliminary themes with each successive interview. Analysis began simultaneously with data collection, and thematic ideas were explored in subsequent interviews where relevant. A master list of themes was reviewed, discussed, and refined in collaboration with 2 members of the research team (AC, LG), who aided interpretation and organization of the data around central organizing concepts and articulation of “the essence” of themes, to arrive at the final thematic structure. Direct participant excerpts from relevant interviews were highlighted in order to elucidate and characterize the thematic findings.

Results

Participants

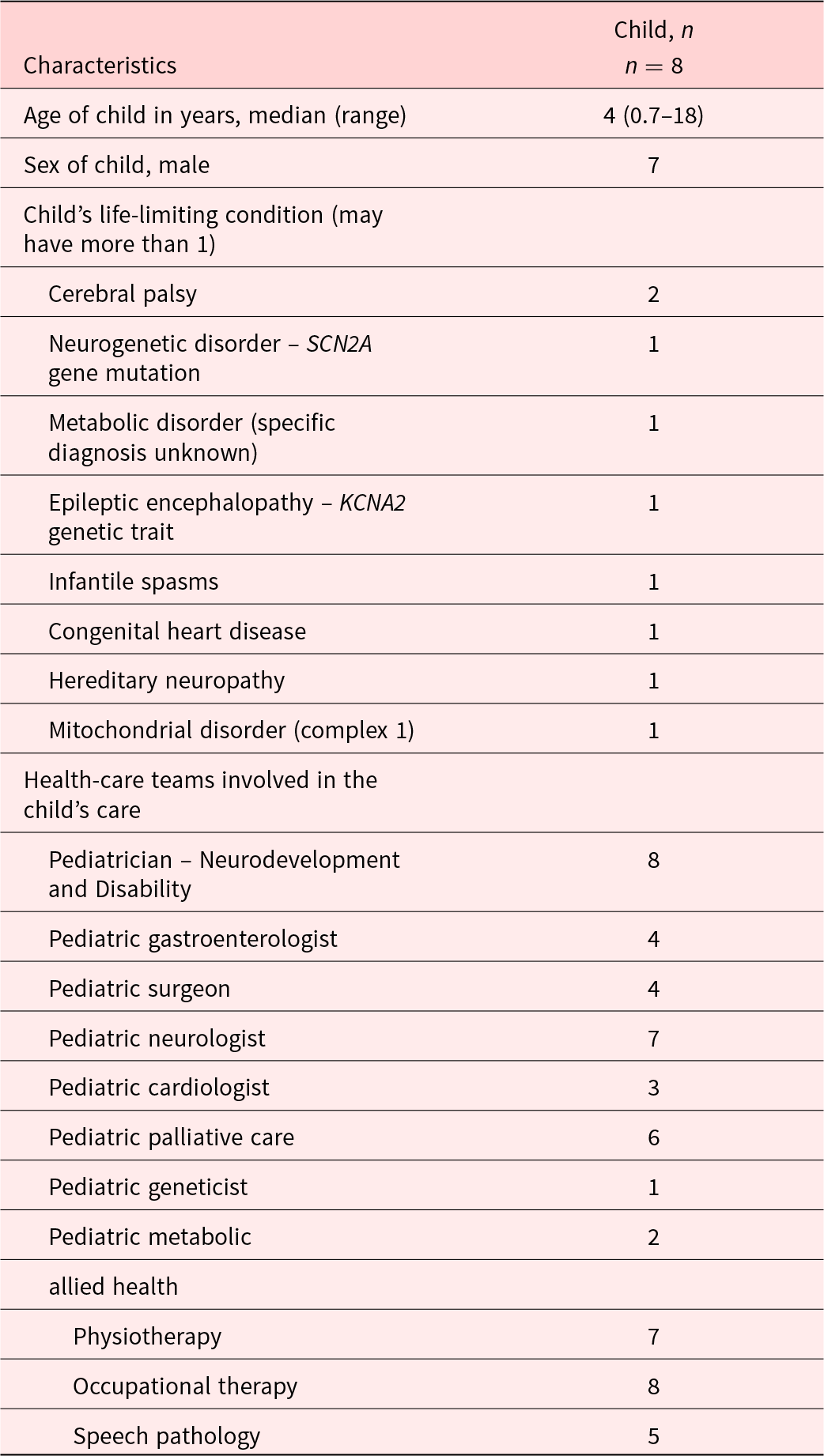

Of the 15 parents approached for study participation, 1 declined and 3 were non-contactable following the initial approach. The final participants included 11 parents (72% female) of 8 children aged between 7 months and 18 years who had various life-limiting conditions (Table 1). One interview was conducted with both parents present and in 2 instances parents of the same child interviewed separately. Children were cared for by a range of pediatric medical subspecialties and allied health teams with some also receiving care from the Palliative Care team.

Table 1. Description of children receiving care

Key findings

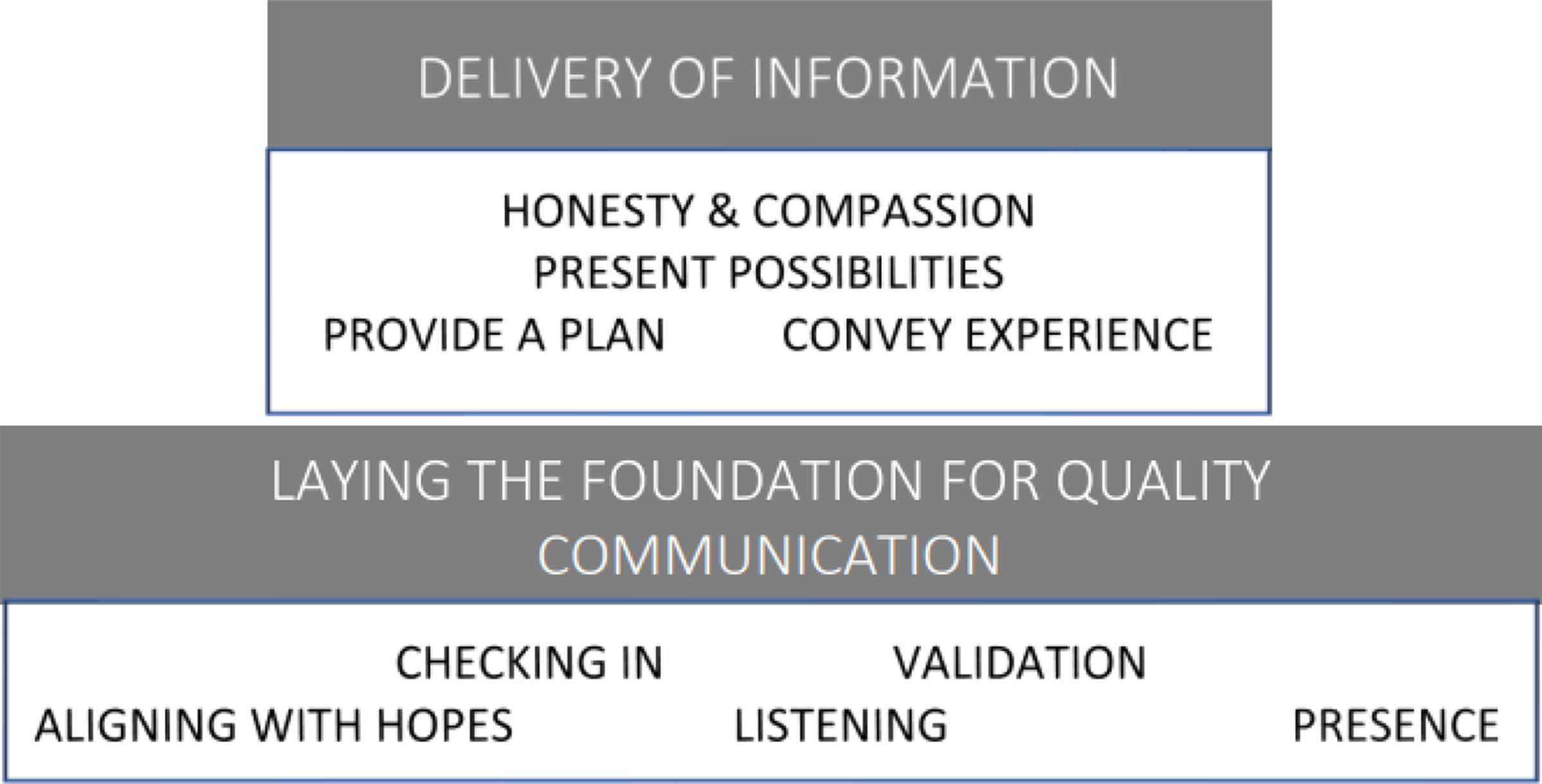

Two major themes constructed from the data represent the parental perspective on approaches to serious illness communication in the context of caring for a child with a life-limiting diagnosis. The first is approaches clinicians can use to lay the foundation for quality communication. The second is approaches clinicians can use to aid the delivery of information. Subthemes characterize each major theme and provide specificity and context. See diagrammatic representation in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Approach to serious illness communication represented diagrammatically.

Theme 1: Approaches clinicians can use to lay the foundation for quality communication

This theme outlines initial steps that clinicians may use to lay the foundation blocks, per se, for quality communication. The analysis of parents’ perspectives highlights the value of checking in, validation, aligning with hopes and a commitment to listening and continued presence.

Checking in

Parents hoped clinicians would practice “checking in” and seek to understand the context for the parent before commencing a discussion with a pre-determined agenda.

How are you feeling about being here.? Is there anything in particular that you’re worried about? […] Is there something that has been on your mind? Do you have any particular questions before we start?

Parent of 3-year-old with epileptic encephalopathy

… you can say ‘Is there anything you want to ask me, or how can I support you right now?’

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Parents also hoped clinicians would be mindful of what they may be prepared to hear at that particular moment in time.

So, when palliative care asked me recently … and they said ‘Do you want to know his prognosis?’… I was really grateful that they bothered to ask, because the answer was no.

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Validation

Parents spoke about feeling disempowered in the health-care system and that the role of the parent needs more recognition. Parents put forward a variety of approaches clinicians might use to provide reassurance through validation.

Parents are innately only trying to feed their children, love their children and not break ‘em… So when you add a carers role to that … it is a whole like smorgasbord […] that we didn’t know we had to do

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

You know your child better than anybody else

Parent of 18-year-old with hereditary neuropathy

Parents also alluded to feeling apprehensive about voicing their worries and advocated for clinicians to create a safe space to raise concerns. One approach was to open the dialogue with a statement of validation. For example,

It just feels counterintuitive to even discuss these things … because you don’t want it to happen … discussing it potentially makes it real

Parent of 3-year-old with epileptic encephalopathy

Aligning with hopes

Parents expressed a desire for clinicians to communicate in a way that aligns with their need to maintain hope. This was perceived to be achieved by using language that promotes continued possibility.

I think that the core message with the uncertainty thing is around reassuring that nothing is set in stone.… It’s not the end of the road. This just doesn’t finish, sort of thing … there is a future and there are people around you to kind of help you through that.

Parent of 2-year-old with cerebral palsy

You know that’s there’s no reversing the damage, but we still don’t know what that means for [child’s name]. So there’s this future that’s still uncertain but it’s also got room for positive …

Parent of 2-year-old with cerebral palsy

Listening

Parents spoke of a fundamental need to feel heard and listened to and how often this had not occurred. Parents provided many examples of an approach that clinicians could use to demonstrate they were listening to the parent and would continue to do so.

Often situations can be made a lot easier very, very quickly, especially with combative parents (who are only frightened) … just by simply going ‘Thank you for being here, I’m listening’… [then] I’m not on the backfoot going ‘Listen to me, listen to me!’

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Presence

Parents spoke of clinicians offering continued presence and the value of knowing their clinicians would be there for them. This was a recurrent theme as parents reflected on their confronting experiences in a highly medicalized world.

Telling people that you’ll be there with them, that they’re never going to be on their own, that there’s never going to be a question that they can’t ask even if that question feels confronting … if you don’t know the right words we’ll sit with you until you do

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Theme 2: Approaches clinicians can use to aid the delivery of information

This theme describes parental perspectives on approaches that can be used when delivering information. Parents reported on ways information can be delivered honestly and compassionately. They reflected on how a clinician’s communication is markedly improved if they are conscious of the impact of their language or what this might convey about the future possibilities for their child. Clinicians should remember to always put forward a plan and recognize that conveying their clinical expertise is empowering for families.

Honesty and compassion

Parents described their wish for information to be delivered honestly and compassionately, even in the context of receiving a poor prognosis.

You know I’m really sorry … it’s not my ideal to be delivering this news by video conference, but I think it’s really important that we do discuss this now. So, you know, I’m [going to] give you this information, [even though] it’s not what we had hoped for.

Parent of 7-month-old with infantile spasms recalling a doctor’s words

The life that they’re going to experience isn’t ordinary, but know you have a team around you who will always listen, who will always support you, and it won’t look like somebody else’s childhood, and it won’t look like their siblings, it will be different, but we are here to walk this journey with you - you’re not on your own.

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Presenting possibilities

Parents spoke of the value of the clinician presenting a range of possibilities when presenting information. Being cognizant of an approach that conveys and describes possibility was perceived to be both informative and hopeful for the parent.

I think for us we just want to know what are the next steps. Scenario A, scenario B, scenario C, or however many scenarios we’ve got … the fact that there’s a variety of pathways in front of this child, though. That’s an important point. So, you know, that is reassuring. And it’s also hopeful.

Parent of 2-year-old with cerebral palsy

He was really gentle and lovely and explained that there is quite a large window. we’re not dealing with like a six-month diagnosis. So there is a window … (and) with a lot of luck and a lot of care … but that said, that window’s still a window

Parent of 3-year-old with epileptic encephalopathy

Providing a plan

In moments of uncertainty and apprehension, parents spoke of the power of a clinician clearly articulating a plan – even if the plan was simple such as explaining the need for careful monitoring and frequent review.

… they were concerned … they will try to figure out the problem … and then they were acting. and it just … it did put my mind at rest,

and

So just be really like clear about what, you know, the expected sort of things are … and clear about the uncertainty levels … like “there’s no chance that we’ll be out within two weeks, but the average is about a month” and that sort of thing

Parent of 4-year-old with congenital heart disease

Conveying the clinician’s experience

Parents reflected on the impact of a clinician conveying their clinical expertise. This was perceived positively by parents who felt reassured about the quality of care their child would receive from an experienced clinician.

I think the word that sticks out, is you know … ‘In our experience’… I know that’s just a simple thing but it kind of gives that there is some form of … you’ve got some experience in it, you know … it’s not just coming from, you know, shooting from the gut kind of thing.

Parent of 6-year-old with an undiagnosed metabolic disorder

Yeah, so, ‘hoping for the best’ like … I don’t want doctors who are hoping … I want doctors who are saying ‘this is the best course of action based on my knowledge’ … I need to know that we’re not like doing any ‘praying’ … get the priests to do that … doctors are doing medicine and the nurses are doing nursing, you know … and we’ll do the praying

Parent of 4-year-old with congenital heart disease

Discussion

Parents have called for research that aims to improve communication with families and that, importantly, recognizes the knowledge and experience that families can bring to the care process and research agenda (Lord Reference Lord2019). This study contributes to this much needed focus through a qualitative exploration of parents’ perspectives on the clinicians approach to serious illness communication. Our findings support literature outlining approaches parents seek from clinicians caring for their loved ones with life-limiting illnesses (Bradford et al. Reference Bradford, Rolfe and Ekberg2021; Collins et al. Reference Collins, Hennessy-Anderson and Hosking2016, Reference Collins, McLachlan and Philip2018; de Vos et al. Reference de Vos, Bos and Plotz2015; Lidén et al. Reference Lidén, Ohlén and Hydén2010).

It is worth noting the literature suggesting that empathy alone is insufficient for difficult conversations (Back and Arnold, Reference Back and Arnold2014). In part, this inspired the aim of this study which was to elucidate the various needs of parents in serious illness communication and how to structure an approach to address them.

Our findings support the literature acknowledging that a family’s health-care journey is dynamic in nature and different approaches to conversations will be required at different times depending on context (Bradford et al. Reference Bradford, Rolfe and Ekberg2021; Koch and Jones Reference Koch and Jones2018). For example, Ekberg et al. reflect on how clinicians can feel compelled, perhaps unnecessarily so, to approach conversations in a recommended way (Ekberg et al. Reference Ekberg, Danby and Rendle-Short2019). The example the authors put forward is introducing the topic of end-of-life explicitly rather than implicitly. Our study findings would support that a conscious act is required on behalf of the clinician to listen for and continually monitor parental needs before proceeding with a predetermined agenda.

DeCourcey et al., in their development of an evidence-based stakeholder-driven serious illness communication program guide (SICG), identified parental needs that correlate with our findings (DeCourcey et al. Reference DeCourcey, Partin and Revette2021). In support of the approach of “checking in,” participants acknowledged that questions should be framed in a way that would seek to understand how much information parents wanted to be provided at the time. Further, their participants asserted that it was empowering to have an approach that allowed parents to reflect on “where they were at.” The approach the SICG employs creates opportunity to align with hopes and for parents to feel listened to when they are directly asked what is important to them. The conversations are revisited repeatedly meaning that health care professionals are offering a continuing supportive presence. The tool guides clinicians to provide a plan. Possibilities are presented as the clinician is guided to address uncertainties. Clinical experience is implicitly conveyed when the clinician is guided to share their understanding of the child’s illness and validation is also implicitly addressed by seeking parental opinion as well as asking about supports in time of difficulty. The authors report on parental perspectives that informed the development of an advance care planning (ACP) tool. While our findings on parental perspectives correlate with those of the authors, we put forward that our findings have broader relevance to improving the quality and provision of serious illness communication that will also occur outside of ACP discussions (Bogetz et al. Reference Bogetz, Revette and Decourcey2022; McLennon et al. Reference McLennon, Uhrich and Lasiter2013). Physicians are most likely to lead conversations using a tool that requires the user to share prognostic understanding with the child or parent. The approaches we outline are intended to have broader applicability in that they may be employed by any member of a multidisciplinary team.

In-depth analysis and study of the content of clinician communication with families is underrepresented in the literature (Kaye et al. Reference Kaye, Woods and Kennedy2021). Further research might well focus on semantics in this care setting given that the literature does report on how our words and language may have significant impact in the palliative care setting. As Cherny concluded, “Words matter […] Words guide us, constrain us, and help us” (Cherny et al. Reference Cherny, de Vries and Emanuel2014). The importance of language was also highlighted by parents in this study.

Language matters because yes it’s every day, pedestrian, to you personally, to you doctors - but not to us.

Parent of 11-year-old with a mitochondrial disorder

Sisk and Malone (Reference Sisk and Malone2018) illustrated the importance of distinguishing the meaning of words and how sharing and reflecting upon this understanding with parents could be therapeutic. For example, speaking to parents about how it is possible to hold onto hope while simultaneously acknowledging a realistic expectation of the eventual outcome.

Triangulating the parental, child, and clinician views on effective communication and exploring how these perspectives evolve longitudinally across the illness course remains an important avenue for further research.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This study was limited by the fact it was conducted at a single site and through 1 specialty medical department. However, the hospital is a well-known tertiary center which meant that parents and their children were cared for by a variety of health-care providers. Given the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictions occurring in Melbourne in 2020, the protocol was required to be amended to allow for online (only) interviews; however, this did not seem to negatively impact upon the quality of interviews or the analysis that ensued. Purposive sampling allowed for wide sampling of differing backgrounds and perspectives; however, similar to existing studies, we captured mostly female (mother) parental caregivers (Macdonald et al. Reference Macdonald, Chilibeck and Affleck2010). With a small sample size, this study was not able to capture the views of those parents who may identify as indigenous or who are non-English speaking. It is likely that communication and information delivery would be even more complex for these families and the perspectives of these parents warrant full attention in future studies.

Conclusion

This study provides unique parent perspectives highlighting 2 major needs of parents that they hope clinicians will bring to routine serious illness communication when providing care for a child with a life-limiting diagnosis. The findings offer parents’ perspectives on approaches clinicians can use in order to lay the foundation for quality communication and deliver information effectively. They provide a guide for the approach a clinician can use to help them create and maintain a therapeutic relationship with the parent. Importantly, results suggest a requirement of clinicians to be flexible with their chosen approach, being aware to actively seek feedback from parents by “checking in.” This enables the clinician to adapt the approach to the context for the parent at any given time. Informed by parents’ perspectives, this study contributes to the evidence base for clinicians caring for a family with life-limiting diagnosis by highlighting the various contexts and needs that might influence their choice of approach to serious illness communication.

Data availability statement

Ethical clearance for this study does not permit data sharing.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the participating parents who so generously gave of their time to share their reflections. Thanks also go to the staff at participating clinical units at the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne and the Paediatric Palliative Care Service at The Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, for allowing time to complete the study and analysis.

Author contributions

NM and AC were responsible for the design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of the work described in the article, and NM as the guarantor accepts full responsibility for the work, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish. IS assisted in the conduct of the work, aiding with screening and recruitment of participants. All authors assisted in the interpretation and the reporting of the work.

Funding

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.