1 Overview

This case study presents innovative work by a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) to use corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a key component of its business strategy in Kenya. AVIC International’s (“AVIC INTL’s”) core business is exporting Chinese machinery and vocational training curricula to enhance the availability of equipment in host countries and to build the capacity of local technical and vocational training institutions. Through active learning with stakeholders in Kenya, AVIC INTL has developed the “Africa Tech Challenge” (ATC) to host training and competitions for candidates from Kenyan technical and vocational institutes. This CSR project, first initiated in 2014, later became a signature CSR project for the company, one which was repeated annually and received Chinese government awards for companies’ overseas brand-building.

The case study shows how CSR can be an effective business strategy for Chinese SOEs operating in African states. Chinese SOEs have started to use CSR projects as a channel for gaining market access, building a positive image both in the host country and in Beijing, and cultivating and deepening ties with host country politicians, industry, civil society, and the (future) labor pool. The study also demonstrates how Chinese SOEs, over the course of overseas operations, have experienced a steep learning curve in host countries with this learning facilitated by SOEs’ interactions with stakeholders in the host country. It discusses how, despite structural asymmetry vis-à-vis China, African actors can actively shape the behavior of Chinese SOEs that are financially powerful and technically strong.

2 Introduction

Why do overseas Chinese SOEs engage in CSR initiatives?Footnote 1 How do SOEs effectively integrate CSR as part of their business strategy? These questions are particularly salient for SOEs working in host countries with relatively weak legal and social institutions to regulate corporate behavior. Global engagement by Chinese SOEs exposes them to new sets of local and international norms and practices that are frequently different from those in China. Many SOEs, during years of operations overseas, have experienced a steep learning curve in acquiring practices and norms from host countries, particularly in countries with sociopolitical contexts starkly different from that of China. CSR has become an area where SOEs can experiment with innovative practices that bring their corporate practices closer to the host country’s normative frameworks.

This case study examines AVIC INTL’s innovative approach of using CSR as a key business strategy in Kenya. It illustrates that in conditions of Sino-African power asymmetry, Chinese SOEs in Kenya learn from their interactions with host country stakeholders and adapt their operations. In 2014, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office rejected the standard approach to CSR as advocated by their headquarters in Beijing and instead initiated the ATC that later became a signature CSR project for the company. The ATC was continued annually and received awards from the Chinese government for effective overseas brand-building. What motivates AVIC INTL to allocate large budgets to this CSR project on an annual basis? Why and how did AVIC INTL create such innovative CSR activities in Kenya? And what was the role of Kenyan stakeholders in shaping AVIC INTL’s CSR initiative?

This case study draws empirical insights from the author’s direct participation in the ATC initiation stage as an early member of the China House, a Kenya-based NGO that participated in ATC’s design and implementation, in 2014. Additional empirical evidence was collected through interviews during multiple field trips to Kenya and China in 2017 and 2019 and follow-up telephone interviews in 2021 and 2022. The study also draws on secondary sources such as AVIC INTL’s CSR reports, internal documents, and email communications with stakeholders on the ATC projects.

The study is organized as follows. It starts by introducing the sociopolitical context of Kenya and Sino-Kenyan relations. Chinese companies operating in Kenya confront a starkly different sociopolitical landscape from their familiar context in China. The study then briefly discusses the Chinese government’s encouragement of Chinese companies, particularly SOEs, to use CSR as a way of overseas operational risk mitigation and it continues by describing AVIC INTL, its shareholding structure, its entry into Kenya, and its core business. The main subsection then elaborates on the initiation and development of ATC from an idea to AVIC INTL’s signature annual CSR project covering multiple African countries, and it concludes with a discussion of key points related to institutional learning, African agency, and the identity of Chinese SOEs as for-profit businesses, policy extensions of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and learning institutions to diffuse innovative overseas practices to China’s domestic business community.

3 The Case

3.1 Background on Sino-Kenyan Relations

Kenya is a lower-middle-income country. The country’s GDP per capita was US$2,007 in 2021,Footnote 2 and GDP per capita growth has averaged 1.3% over the past five years, above the regional average. In 2020, Kenya surpassed Angola to become the third largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa after Nigeria and South Africa, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). From 2015 to 2019, Kenya’s economy achieved broad-based growth averaging 4.7% per year, significantly reducing poverty (which fell to an estimated 34.4% at the US$1.90/day line in 2019).Footnote 3 Tourism in Kenya is the second largest source of foreign exchange revenue following agriculture. In 2020, the COVID-19 shock hit the economy hard, disrupting international trade and transport, tourism, and urban services activity. IMF evaluation shows that Kenya’s economic rank in sub-Saharan Africa dropped to seventh in 2021. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 further exposed Kenya’s economy to commodity price shocks, particularly as Kenya’s economy is vulnerable to the cost of fuel, fertilizer, wheat, and other food imports.Footnote 4

Kenya has one of the more vibrant media landscapes on the African continent, with professional and usually Western-trained journalists serving as watchdogs. The country’s media is highly competitive and diverse, with over 100 FM stations, more than 60 free-to-view TV stations, and numerous newspapers and magazines. Journalists in Kenya, like in many other African countries, have long been trained with Western curricula, which produces a media system that is “an appendage of the Western model” of journalism.Footnote 5 Kenya also has an active civil society organization (CSO) sector, and trade unions are active with approximately 57 unions representing 2.6 million workers in 2018.Footnote 6 Journalists and CSOs critically assess the operations of domestic and foreign businesses and politics.

In Kenya, like many other African countries, Chinese media reporting tends to be less appealing and less popular than news from Western media sources despite Beijing’s emphasis on soft power and discourse power.Footnote 7 In 2009, China’s central government committed US$6 billion to facilitate Chinese media “going out” and competing with Western media conglomerates.Footnote 8 In 2012, CGTN, the main Chinese global media station, opened its Africa headquarters in Nairobi and China Daily launched its Africa edition. Xinhua News Agency and China Radio International have also been active in their outreach to the continent. China even carried out media training programs for African journalists in China, with the hope that the journalists would portray China in a more favorable light upon returning home but with mixed results.Footnote 9 In fact, interviews and surveys with African residents found Chinese media outlets to be unappealing. Local interviewees were largely unaware of CGTN,Footnote 10 and a survey of young private sector employees in Nairobi showed that CNN, a US media outlet, was the most watched foreign media channel.Footnote 11

3.2 Kenya–China Relations

China established diplomatic relations with Kenya only two days after Kenya gained independence from the United Kingdom in December 1963. China was the fourth country to open an embassy in Nairobi. Bilateral relations gained momentum when President Daniel arap Moi came to power in 1978 and Deng Xiaoping in China pushed for “Opening and Reform.” The Sino-Kenyan relationship gained momentum with high-profile visits and agreements to promote trade, investment, and technology exchange, as well as military exchange.

China is Kenya’s largest trading partner and largest source of imports. In 2020, Kenya imported US$5.24 billion’s worth of highly diversified products from China, with textiles, chemicals, metals, electronics, and machinery representing the main sectors. In the same year, Kenya exported just US$123 million’s worth of products to China, predominantly minerals and agricultural products (see Figure 2.1.1). Kenya’s approach of exporting raw materials to China and importing manufactured products from China conforms to China’s bilateral trading pattern with many non-resource-rich African countries.Footnote 12

Figure 2.1.1 Kenya’s export basket, 2020

Kenya is the fourth largest destination of Chinese loans in Africa after Angola, Ethiopia, and Zambia. From 2000 to 2020, China extended US$9.3 billion of loans for transport, power, ICT, and other sectors.Footnote 13 The largest and most expensive project in Kenya supported by Chinese loans is the Standard Gauge Railway Phase I (US$3.6 billion) and Phase 2A (US$1.5 billion). Since 2017, however, concerns over Kenya’s debt sustainability and whether China uses debt to seek control over strategic assets such as railways and the Port of Mombasa have generated extensive debate in Kenya and internationally.

The two countries have starkly different sociopolitical systems. China is home to one of the world’s most restricted media environments with a sophisticated system of censorship.Footnote 14 The publication of the law on foreign nongovernmental organizations in 2017 and the 2016 legislation governing philanthropy significantly reduced CSOs’ access to funding from foreign sources and increased supervision and funding from the government. There is only one legal labor union organization, which is controlled by the Chinese government, and which has long been criticized for failing to properly defend workers’ rights.Footnote 15 Chinese companies operating abroad in highly different sociopolitical contexts such as in Kenya frequently find themselves stepping into unfamiliar situations such as environmental and community welfare activism, labor unions, and media watchdogs. Kenyan employees of Chinese SOEs may resort to strikes to force the management to negotiate on wage and benefits, issues that Chinese managers are ill-equipped to deal with and which are a source of tension that reveal large cultural and management style differences.Footnote 16 The sheer size and visibility of the multibillion-dollar projects that Chinese SOEs work on, with frequent visits from high-profile local politicians as well as Chinese and other international political celebrities, draw these projects into the media spotlight. Used to highly controlled media serving as a mouthpiece of the Chinese government, Chinese SOEs find themselves beleaguered by “biased” criticism in local and international newspapers and other outlets. As a result of these challenges, Chinese companies frequently find it challenging to adapt their operation to the Kenyan situation. One response is the defense mechanism of “keeping a distance with respect” (jing’er yuanzhi).Footnote 17

3.3 Doing CSR Overseas

The Chinese government has encouraged CSR domestically and published CSR regulations for overseas projects, yet implementation has been slow because these regulations are largely voluntary in nature and have weak implementation monitoring requirements. To coincide with the global expansion of Chinese companies and the ongoing evolution of the BRI, government agencies at both central and provincial levels issued 121 guidelines and regulations between 2000 and 2016, mostly voluntary, requiring Chinese companies overseas to perform CSR or improve environmental, social and governance (ESG) domestically and overseas.Footnote 18

In response to external criticism of Chinese companies’ overseas behavior, Beijing recalibrated the BRI and promoted new regulations to oversee its implementation.Footnote 19 For instance, in 2016, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce started to publish annual social and political risk assessments and held training programs for Chinese overseas investors. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China published the first Belt and Road Green Bond at the Summit in 2019. The Environmental Protection Agency committed to training 1,500 officials in BRI countries and establishing technology exchange and diffusion centers along the Belt and Road.Footnote 20 However, the majority of these are also nonmandatory, and Beijing’s regulatory bodies cannot exercise effective control and oversight of all BRI activities conducted locally or abroad.Footnote 21

3.4 AVIC INTL and the TVET Project in Africa

China Aviation Industry Corporation (AVIC) is a central SOE specializing in aerospace and defense and headquartered in Beijing. It was founded on 6 November 2008 through the restructuring and consolidation of the China Aviation Industry Corporation Ι (AVIC Ι) and the China Aviation Industry Corporation ΙΙ (AVIC ΙΙ).Footnote 22 AVIC’s business units cover defense, transport aircraft, helicopters, avionics and systems, general aviation, research and development, flight testing, trade and logistics, assets management, financial services, engineering and construction, automobiles, and more. It is ranked 140th in the Fortune Global 500 list as of 2021,Footnote 23 and, as of 2021, has 1,003 subsidiary companies, including 63 second-level subsidiaries, 281 third-level subsidiaries, 340 fourth-level subsidiaries, 261 fifth-level subsidiaries, and 14 seventh-level subsidiaries, with 24 listed companies and 400,000 employees across the globe.Footnote 24

AVIC International Holding Corporation (“AVIC INTL”) is a global shareholding enterprise affiliated to AVIC. Also headquartered in Beijing, it has six domestic and overseas listed companies and has established branches in sixty countries and regions.Footnote 25 In 2008, AVIC INTL became an independent subsidiary company engaging in nonmilitary activities, including project planning, project financing management, export of electromechanical products, general contracting, operation, and maintenance of overseas engineering projects. AVIC INTL Project Engineering Company (“AVIC INTL-PEC”) was formally the International Projects Department under AVIC INTL and became a separate company in May 2011, also headquartered in Beijing. The company specializes in four main businesses: (1) people’s livelihood projects, including exporting Chinese mobile hospital equipment, vocational training equipment, container inspection system, buses, and so on; (2) energy engineering, procurement, and contracting, notably the Atlas Power Station Project in Turkey; (3) infrastructure construction, such as the rebuilding and expansion of a Kenyan airport project; and (4) industrial facility construction. The shareholding structure of AVIC INTL-PEC is illustrated in Figure 2.1.2.

Figure 2.1.2 AVIC INTL-PEC shareholding structure

AVIC entered Kenya in 1995 to export Chinese military aircraft to Kenya and established AVIC INTL Kenya representative office on 2 June 1995. Subsequently, AVIC INTL-PEC, AVIC INTL Beijing (covering businesses including cement engineering, petrochemical engineering, electromechanical engineering, and import and export of heavy equipment), and AVIC INTL Real Estate (newly established in 2014) were established in Kenya. When bidding for projects in Kenya, AVIC INTL-PEC, together with other subsidiaries, used the name of the parent company AVIC INTL because it had a bigger branding effect, but in reality these subsidiaries operate relatively separately, having offices in different compounds. AVIC INTL-PEC has engaged in three main projects: the National Youth Service (NYS) Phase I and II,Footnote 26 Technical, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training (TVET) Phase I and II, and the Karimenu dam water supply project.Footnote 27

3.5 TVET Phase I

AVIC INTL’s TVET project was developed with the Kenyan Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MOEST) and involves equipment provision and capacity-building for Kenyan technical and vocational training institutions. In 2008, a MOEST delegation visited China and raised a request to import Chinese machineries and training in support of Kenyan TVET institutions. In 2010, AVIC INTL signed a Memorandum of Understanding with MOEST for US$30 million for Phase I of the TVET project. The following year, the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) signed an agreement with the Government of Kenya, providing a US$30 million concessional loan in support of this TVET Phase I. The terms of this loan were set at 2% interest rate, twenty-year maturity, and a seven-year grace period. The loan was scheduled for semi-annual repayment between March 2018 and September 2030.

The purpose of the project was to establish ten vocational and technical institutes in Kenya and provide training to 15,000 students.Footnote 28 The implementation of the first phase of the project mainly focused on two parts: equipment supplies and course training. This includes providing electronic and electrical goods, mechanical processing, rapid prototyping experimental training equipment, diesel generator sets and corresponding spare parts, supporting facilities for ten affiliated colleges and universities, as well as providing college planning, professional settings, and course packages, including compiling textbooks, laboratory planning, teacher training, assessment and evaluation, integration of production and education, and academic exchanges.Footnote 29

3.6 TVET Phase II

In September 2013, AVIC INTL signed the TVET Phase II contract with MOEST at a cost of US$284 million.Footnote 30 This figure was later revised to US$167 million via Addendum No. 1 of the contract. The contract value was then further revised to US$159 million via Addendum No. 2 dated 25 May 2016, after the Government of Kenya opted to undertake the civil works itself, while leaving the supply, installation, and commissioning of the equipment as well as human capacity-building to AVIC INTL. According to the contract, AVIC sought to equip a total of 134 educational institutions and provide training across the country. It was stipulated that 1,500 teachers were to be sent to the field and 150,000 students were to be trained by 2020. Exim Bank’s approval for financing was pending for three years. It was not until 2017 that Exim Bank signed an agreement to provide an additional US$158 million of commercial loans for TVET project Phase II.

3.7 Challenges during TVET Phase I Implementation

By 2013, however, the imported equipment from TVET Phase I had not been used to its full capacity. A review of the project by Kenya’s Auditor General revealed that one university and nine technical training institutes had been supplied with electrical/electronic engineering, mechanical engineering, rapid prototyping manufacturing laboratories, and diesel generators, but a physical verification of the equipment in all of the ten institutes revealed that the equipment had not been utilized to full capacity and the generators had not been put to use.Footnote 31 AVIC INTL’s progress report to Exim Bank in June 2013 also recognized the limitation of existing infrastructure and the gap between Kenyan and Chinese higher education.Footnote 32 AVIC INTL’s then project manager Li explained these two points in detail.Footnote 33 First, many remote towns in Kenya cannot provide stable electricity, and unstable electric current risks damaging expensive equipment. Second, teachers in TVET institutions, even after weeks of training in China, were still not sufficiently skilled to operate the machines, let alone teach students. For the training, AVIC INTL partnered with Inner Mongolia Technical College of Mechanics & Electrics to design the curriculum and carry out the training, but the language barrier was a key obstacle. Chinese trainers from the college traveled to Kenya and taught through translators but misinterpretation and the need to use technical jargon resulted in misunderstandings.Footnote 34 AVIC INTL needed to show that Phase 1 was successful to secure follow-on finance. However, implementation of Phase 1 on the ground was far from successful with some brand-new machines purchased from China laying idle.

3.8 A CSR Innovation: Africa’s Tech Challenge

To secure Exim Bank’s funding approval for Phase II, AVIC INTL needed to show that Phase I was a success. An endorsement letter from the Chinese Economic Councilor in Kenya was a crucial step toward securing Exim Bank funding and Liu, the then deputy CEO of AVIC INTL, took a short trip to Kenya in late January 2014. There was a dinner meeting with Han Chunlin, the then Chinese Economic Councilor to Kenya. When Han asked about the progress of AVIC INTL’s projects in Kenya, Liu reported on the progress of TVET Phase II and reflected on the experience of implementing Phase I, which had been completed by the end of 2013. He said that, in Phase II, AVIC INTL would further commit, and explore possible solutions, to ongoing issues even beyond the contract framework, such as providing raw materials and manufacturing contracts to schools and ensuring that the products could be used in other AVIC INTL projects in Kenya. By then, the company had already signed a contract with MOEST regarding TVET Phase II and were applying to Exim Bank for a loan thus requiring the endorsement letter from the Economic Councilor.

This was also the time when AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters were considering conducting a CSR project in Kenya. The then AVIC INTL’s TVET project manager Li was also at the dinner that evening. Months later, he went on a trip to visit schools in the western provinces of Kenya with Isalambo S. Shikoli Benard, his counterpart from MOEST. On 21 February, on their way to Turkana, Li received an email from AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters in Beijing informing him of the headquarters’ interest in developing a CSR project in cooperation with the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA). CFPA approached AVIC INTL headquarters in Beijing and proposed a CSR project featuring the provision of scholarships to African students to continue their study locally or in China. This was relatively easy to prepare and coordinate; CFPA already had rich experience of this type of corporate philanthropy in China. AVIC INTL headquarters allocated RMB 1 million (approx. US$16,000) for the Kenyan office to implement the project in collaboration with CFPA. AVIC INTL’s Kenyan office was selected because it was the first office to carry out an education-related program.Footnote 35 In the email, AVIC INTL headquarters indicated their plan to form a research team with the Corporate Culture Department and three managers from CFPA for a nine-day field trip to Kenya in March 2014 to carry out a feasibility study of this CSR project. Li was asked to coordinate with local stakeholders to prepare for this fieldtrip but was far from enthusiastic about CFPA’s proposal. During the seven-hour drive, Li and Benard discussed this scholarship project and Benard was equally unimpressed.

This prolonged driving trip was an ideal place for Li and Benard to brainstorm CSR project ideas. Benard’s team in MOEST had previous experience of hosting the “Robot Contest” and the winner was named “African Tech Idol.” The idea was to use robot assembly as an entry point to promote engineering and provide a forum for young engineers to display their creative works, exchange ideas, and promote engineering. Sponsored by Samsung, the fourth contest was to be held at TVET institutions.Footnote 36 Drawing on MOEST’s multiyear experience of successfully hosting the Robot Contest in cooperation with Samsung, Li and Benard borrowed this idea and applied it to AVIC INTL’s CSR project to host a technical skills competition using equipment installed by AVIC INTL. When they finally arrived at a village around midnight, Li emailed back to the senior management of AVIC INTL-PEC, copying in Liu, and warned of three difficulties in implementing the scholarship project including the recipient selection criteria, monitoring and evaluation, and most importantly, the corrupt nature of the client ministry:

The scholarship distribution has to rely on Kenyan Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, and the coordination process may induce corruption. Referencing to previous scholarship programs in cooperation with the Ministry, the scholarship tends to end up [more often] in the hands of some connected individuals than the most needed; or the money was simply divided up within the Ministry before they even reach the students.Footnote 37

In the same email, Li briefly outlined his discussion results with Benard on an alternative “Africa’s Tech Idol” project:

Name: Africa’s Tech Idol (tentative)

Potential candidates for the first season: Kenya Vocational and Technical College (about 30)

Two rounds of competition for the first season:

1. The preliminary round: machining competitions are held in five regions in Kenya and the top two in each region will be determined.

2. The final round: ten teams compete in machining at our workshop at Kensington University. We provide the design, and the team can choose their equipment, including ordinary and numerical control equipment.

The winning team will be rewarded:

1. Offered a production and processing contract on the spot.

2. Will be supported by our technicians in the factory.

3. We process raw material support.

4. A certain amount of project funding (in the form of sponsorship or angel funding) or equipment sponsorship, or both.Footnote 38

Sun and Qi (2017) had a subsequent quote from Benard explaining his attitude toward the traditional types of CSR and his enthusiasm toward the skills competition:

They [the AVIC International staff] were saying, “we could build a hospital…” I said, “All that is good, but it is being done by many people. But where you’ll have impetus: you’ve given us huge equipment, but the equipment is just here. We’re not utilizing it. So, if we have a competition to support this equipment, then really, you’ll be helping us as a country to build the confidence of our students that they can make things which can actually go out there.”Footnote 39

Benard drafted a project proposal for the creation of what eventually became the “Africa Tech Challenge” soon after returning from the Turkana trip.Footnote 40 In MOEST, Benard also sought higher administrative support from the Ministry. On AVIC INTL’s side, Li’s team sent the “Africa Tech Challenge” proposal back to Beijing for approval at the headquarters level. In comparison, the CFPA’s scholarship program gradually lost support from the AVIC INTL leadership.

In addition to MOEST’s experience in hosting skills competitions, Li also drew from the Japan International Cooperation Agency’s (JICA’s) extensive support of the Nakawa Vocational Training Institute in Uganda and also the experiences of Japanese companies in conducting CSR and other philanthropic projects – information shared via Li’s friend who was working in the Japanese Embassy in Uganda at the time.Footnote 41 Li’s friend was part of JICA’s Nakawa Institute project and, following his friend, he shadowed meetings with the project stakeholders in Uganda. When Li visited the Nakawa Institute, he was impressed to see that JICA’s malfunctioning vehicles were sent to Nakawa for maintenance. During the two decades of JICA’s cooperation with Nakawa, there was not only education but also a combination of “production and education” (chanjiao jiehe) projects in Nakawa, bringing business benefits to the institution in addition to training students. In his proposal to AVIC INTL headquarters, Li also cited the Toyota Academy and Huawei Training Centre in Kenya as successful examples of vocational training.

Upon initial confirmation from AVIC INTL headquarters of the idea of “Africa Tech Challenge,” Li and Mwangi, a Kenyan manager of AVIC INTL’s TVET project who used to study in China and speaks and writes Chinese fluently, developed the idea into a full concept note in March 2014. Mwangi’s family was well-connected in Kenya, and through her family network AVIC INTL managed to mobilize the then vice president (and president since 2023) William Ruto for the “Africa Tech Challenge” ceremony. Through his personal network, Li met the founder and CEO of China House, Huang, a Columbia University graduate and freelancing journalist who had created a Kenya-based CSO to help connect Chinese companies and Kenyan local communities. In his emails with AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters, Li mentioned China House and explored the possibility of contracting with China House to help with the development of AVIC INTL’s CSR project. Li wrote in his email to AVIC INTL headquarters:

Huang is very familiar with the media. At the time [of the competition], we will need the help of such talents in media public relations and writing various English reports… China House can recruit excellent summer volunteers to help us solve the labor shortage during the busiest season of AVIC INTL’s Kenya office.Footnote 42

Seeking to secure the first project, Huang’s friendship with Li led to a service contract between AVIC INTL and China House on the ATC in June 2014. China House recruited two full-time staff for the delivery of AVIC INTL’s contract. Among others, China House’s main responsibilities included (1) coordinating ATC stakeholders, including MOEST, public relations companies, social media, and the United Nations; (2) publicizing the ATC via China House’s own channels; and (3) providing a project evaluation summary report on the ATC’s effects to participants and media. Huang brought in his media connections and sensitivity to the ATC’s implementation and the involvement of China House was key to the development of the ATC.

Li convinced AVIC INTL headquarters to conduct the ATC as a machining skills competition in cooperation with MOEST. Li, with the help of the Ministry and together with China House, visited twenty-six out of forty-six TVET institutions in Kenya and received twenty-nine team applications, with three members in each team. Each school could nominate one or two teams with one advisor who was responsible for the organization of the participants. In the preliminary round, eighteen teams were selected and the top six then participated in the final competition. After twenty-three days of training, three winning teams were awarded US$100,000 in machine parts contracts and three individual awards with opportunities to continue education in China.Footnote 43 AVIC INTL subcontracted with the Inner Mongolia Technical College of Mechanics & Electrics to design the short training curriculum and flew two teachers from Inner Mongolia to Nairobi to train Kenyan candidates and prepare them for the competition. The ATC started in late July 2014 and the final competition was held on 5 September.

AVIC INTL’s Kenyan office developed the ATC and media relations strategy not through imposition or borrowing experience from Beijing headquarters but from the company’s interaction with stakeholders in Kenya. In addition to China House, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office also contracted with a Kenyan public relations (PR) company to run the ATC opening and award ceremonies and media engagement. Invited leaders from AVIC INTL and its parent company, the Chinese Ambassador, the Economic Councilor, the Kenyan Minister of Education, Science and Technology, and other government leaders attended the awards ceremony, which attracted wide media coverage. In fact, PR was a key component of ATC from the project design stage onward. PR costs represented 24% of the total ATC budget with expenses including PR company service fees, social media company service fees, and billboard rental and printing fees. AVIC INTL rented a billboard in Nairobi’s busy Harambee Avenue for multiple weeks. The ATC project evaluation report conducted by China House showed that the media influence of ATC included fifty-three media items at various stages of the ATC, including the opening and award ceremonies, during training, and the candidates’ recruitment. Nine out of the fifty-three pieces were from Chinese media groups in Kenya with the remainder from Kenyan and African media. Western media groups were absent.Footnote 44

The first ATC emphasized entrepreneurship and women’s empowerment as key themes beyond general skills training. The theme of entrepreneurship was implemented through ATC Talk, mimicking the format of a TED Talk. This idea emerged from a brainstorming session between Li’s team, China House, and the local PR company. The PR company invited successful Kenyan entrepreneurs and young leaders to communicate face-to-face with the students to share their entrepreneurial experiences and growth stories. In August and September 2014, three Kenyan entrepreneurs were invited to give talks to ATC candidates to create opportunities for candidates to interact with local businesses. Invited entrepreneurs shared their thoughts on topics such as “How to become an entrepreneur” by Samuel Kasera, CEO of Mutsimoto Motor Company, and “From student to entrepreneur: dream or reality” by David Muriithi, CEO of the Creative Enterprise Centre. The theme of women’s empowerment was addressed by making sure to give at least one female candidate the opportunity to study in China.Footnote 45 Charity, the only female winner among three candidates who were awarded a scholarship, continued her study at Beihang University in China and was featured in AVIC INTL’s short movie, A Kenyan Girl’s Dream to Become an Engineer.

The success of ATC resulted in AVIC INTL highlighting it as the company’s signature CSR project to be held annually. The ATC was an innovative idea for AVIC INTL, whose existing CSR projects were educational philanthropy, a signature project being a rural teacher training program named “Blue Chalk.”Footnote 46 It was also AVIC INTL’s only overseas CSR project. Each year, the ATC was featured in AVIC INTL headquarters’ annual documentary series, Glories and Hope. Although the revenue of the TVET project cannot compete with major construction projects from other AVIC branches, the ATC project was so unique that Li was awarded AVIC INTL “Best Overseas Employee.” The success of ATC Season I earned AVIC INTL wide media coverage in Kenya, enhanced client relationship with MOEST, and boosted Chinese domestic recognition.

Publicity for the ATC in China has not been as systematic as overseas in Africa where AVIC and China House’s connections were based. In explaining why the ATC’s overseas publicity is more important to AVIC INTL than domestic publicity in China, the current TVET project manager Yang explained: “We mainly target the overseas market, so domestic publicity is not very focused. At AVIC level, when they receive notifications from the government, AVIC sometimes requests us to report the ATC case.” The ATC project won the “2020 Excellent Case for Chinese Companies Overseas CSR Award,” an annual award jointly organized by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council Information Center, the China Press Office of the China International Publishing Administration, and the International Communication and Culture Center of the China Foreign Publishing Administration.Footnote 47 Utilizing its mobilization strength among university students in China, China House has also presented the ATC as a successful activity during policy conferences and student meetings.

Starting in Season III, ATC expanded beyond Kenya with teams invited from Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia. Cooperation with China House, however, finished. Since then, the ATC has become more closely aligned with AVIC INTL’s TVET project and women’s empowerment and entrepreneurship elements have not been featured.

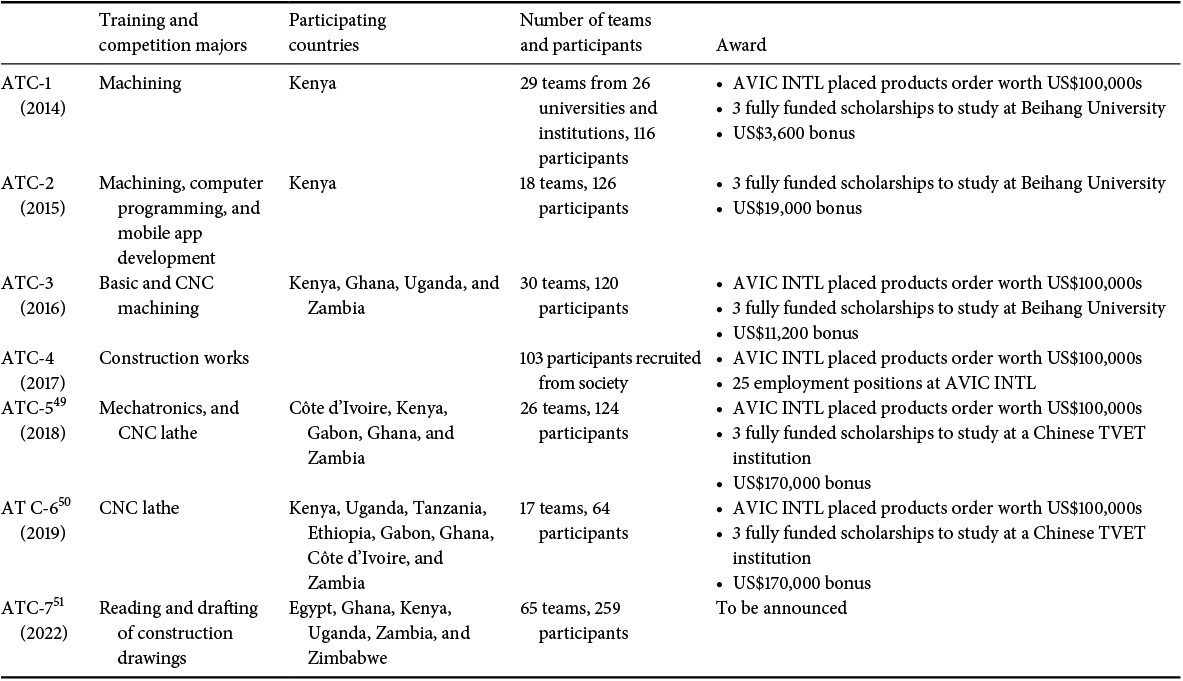

Since 2014, ATC has been held once a year, and as of 2019, it has successfully held six competitions (see Table 2.1.1). Each year, AVIC INTL allocates approximately RMB 3 million to the event.Footnote 48 Due to the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the event was temporarily suspended, but in July 2022, after suspension for two years, ATC Season VII launched online. The training was also conducted online through a newly developed app that AVIC INTL developed to use for its TVET projects in response to the pandemic and expanding business globally. The preliminary round of ATC VII has expanded to 42 schools entering 65 teams from six countries, namely Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, and a total of 259 students.

Table 2.1.1 The seven ATC seasons and coverage

| Training and competition majors | Participating countries | Number of teams and participants | Award | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATC-1 (2014) | Machining | Kenya | 29 teams from 26 universities and institutions, 116 participants |

|

| ATC-2 (2015) | Machining, computer programming, and mobile app development | Kenya | 18 teams, 126 participants |

|

| ATC-3 (2016) | Basic and CNC machining | Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia | 30 teams, 120 participants |

|

| ATC-4 (2017) | Construction works | 103 participants recruited from society |

| |

| ATC-5Footnote 49 (2018) | Mechatronics, and CNC lathe | Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, and Zambia | 26 teams, 124 participants |

|

| AT C-6Footnote 50 (2019) | CNC lathe | Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Zambia | 17 teams, 64 participants |

|

| ATC-7Footnote 51 (2022) | Reading and drafting of construction drawings | Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe | 65 teams, 259 participants | To be announced |

Yang, the current AVIC INTL’s TVET project manager, who was in charge of ATC, explained how this CSR project is being used to develop AVIC INTL’s main TVET business. ATC’s participating countries are usually the ones the company has already had TVET projects in or in which it plans to cultivate TVET cooperation:

We approached officials from the respective country’s Ministry of Education or their Vocational Education Department under the Ministry when we invited them to form teams to participate in the ATC, and for the award ceremony, we invited them over to Nairobi to attend. Similarly, we invite headmasters of TVET institutions in these countries. For each country, we have two official invitation quotas for the ATC award ceremony, and more Kenyan government officials are invited. At the third season of ATC, the current president-elect, William Ruto came.Footnote 52

This quote shows that the SOE smartly connects its CSR project to business development and market expansion. Although business development has not been made directly through the ATC, this platform is used to cultivate and maintain relationships with the leadership from TVET institutions and government officials of the target countries.

4 Conclusion

The ATC, AVIC INTL’s signature CSR project, is an example of a multinational company’s willingness to adapt to host country situations. First, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office demonstrated a learning curve with respect to CSR norms and practices in the host country. Over time, AVIC INTL developed an innovative and successful CSR project with an elevated PR strategy and aspects of gender equality and youth entrepreneurship. Second, the SOE’s project manager actively learned through interacting with a variety of stakeholders in Kenya through his personal and professional networks. Project manager Li incorporated expertise from Kenyan counterparts and drew on his knowledge of Japanese corporate practices and JICA projects to come up with tailored solutions appropriate for his project. MOEST’s successful multiyear experience of hosting the Robot Contest, in cooperation with Samsung’s CSR department and China House’s media relations and public engagement expertise, all contributed to the development and implementation of the ATC. Finally, the SOE’s internal structure may serve as a channel for the diffusion of good practices from field offices to Beijing headquarters and further spread to other Chinese companies through government promotion. Through AVIC INTL’s internal structures, information and experiences from the SOE’s field offices in Kenya were applauded by their headquarters in China and shared in internal meetings. The ATC as a case study also received an award from the Chinese government and was promoted to the wider SOE community.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

Upon completion of TVET Phase I, AVIC INTL identified the lack of usage of the machines they provided, which could potentially harm their success of securing Phase II funding from Exim Bank. Mediocre implementation on the host state side is a problem that extends well beyond the TVET case, and thus has broader significance for analyzing China–Africa projects. In the TVET case, substandard implementation was also the motivation for the company to innovate on a CSR project that could “train the trainers” to run the machines. To address the problem, AVIC INTL could have pursued a number of different strategies. For example, instead of initiating the ATC, another approach would have been for AVIC INTL to resort to litigation or other formal dispute resolution means. What are the legal merits for AVIC INTL’s claim should it want to sue the Kenyan government for not implementing its part of the contract? What are the potential risks for AVIC INTL if it pursued a legal rather than CSR route to solve the challenge? Do you agree with the company’s decision for not resorting to legal procedures?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

The ATC case raises two main questions with policy relevance. First, are CSR activities instruments of Beijing’s global soft power outreach or are Chinese SOEs making genuine progress toward localization and further internationalization? And are these mutually exclusive explanations? Arguably, Chinese SOEs, particularly their CSR activities, are part of Beijing’s broader soft power projection in Africa. Indeed, it is frequently perceived that Chinese SOEs, particularly given their state-owned nature, sometimes have broader, noncommercial aims providing a pivotal role in establishing connection between the Chinese government, local media outlets, and universities to promote a positive image of China in Africa. This case study, however, shows a CSR initiative developed by an SOE’s Kenyan subsidiary after the Kenyan project manager rejected the original CSR project proposal from the SOE headquarters. Following its success, the CSR project was then promoted by the SOE headquarters and the Chinese government as creating business development opportunities and as an example of corporate stewardship overseas. This case may thus show less a coordinated effort by the Chinese government in Beijing and more a localized learning endeavor by the SOE’s Kenyan subsidiary seeking to advance its business through an innovative and targeted CSR project. At the same time, in spite of the fact that the project was driven by local needs and interests, such facts are not to say that the Chinese government in Beijing could not then use the project for its own soft power benefits. Discuss these alternatives.

Second, is ATC an example of African agency or Chinese agency? Is China in Africa more precisely perceived as a global power exercising influence in small states? Or should we see this relationship as an interactive process where both parties have the agency to shape outcomes? We may emphasize the structural asymmetry between global economic and political strengths between smaller African countries and China, the world’s second largest economy and a rising power. In dealing with Chinese SOEs, we may perceive Kenyan bureaucrats, media, and CSOs as lacking the agency to shape the behaviors of Chinese SOEs to their benefit. An opposing perspective is to view Chinese SOEs’ activities in African countries, and in this case, AVIC INTL’s CSR initiatives in Kenya, as jointly shaped by Chinese managers and a variety of Kenyan actors. Discuss these diverging perspectives.

5.3 For Business School Audiences

AVIC INTL’s innovation underlines how CSR could help address several operational risks and opportunities for the overseas endeavors of Chinese SOEs and multinational corporations in general, particularly those operating in developing countries. What drives multinational companies’ CSR activities? The ATC case shows that in countries with relatively weak social and environmental regulations, CSR could help multinational companies earn the social license to operate and reduce compliance risks. In countries with strong socio-environmental protection laws that are strictly implemented, these legal regulations serve as a guidance for multinationals, particularly those that newly entered a market, to develop amiable community relations and avoid local pushback against their products and operations. In countries where the implementation of socio-environmental regulations is relaxed or even incomplete, how could companies use CSR activities to help them navigate community relations in host countries?

Second, the ATC case also demonstrates an opportunity for companies to strategically connect CSR and business development activities. How specifically did AVIC INTL manage to achieve this connection? In AVIC INTL’s case, the ATC’s success motivated the company’s leadership to further invest in the project and connect it to market expansion opportunities in neighboring African countries. In other words, this is a bottom-up and ad hoc connection between CSR and business development. What are options for companies to cultivate this connection? Could top-down design provide an alternative (or complementary) strategy?