Introduction

The mid-1880s witnessed two significant shifts in the policies of the German Empire (Deutsches Kaiserreich). First, it acquired in less than a year, from 24 April 1884 to 27 February 1885, Protectorates (Schutzgebiete) over Southwest Africa, Cameroon, Togo, and German East Africa.Footnote 1 Other colonies in Asia and the Pacific would follow in the second part of the 1890s, transforming Germany into one of the largest colonial empires of the time. Second, the Royal Prussian Settlement Commission (Königlich Preußische Ansiedlungskommission) was created in 1886 to purchase large Polish estates and sell them in smaller plots to German-speaking settlers in the eastern provinces of the German Empire and thereby spur the ‘Germanisation’ of territories with large Polish-speaking communities. These events are commonly framed, in the social sciences and beyond, as belonging to different analytical spaces, namely, on the one hand, the expansion of the German colonial empire and, on the other, policies of internal nation building within the Kaiserreich. Literature on connections and entanglements has focused on how to overcome these ‘analytic bifurcation[s]’ for some time.Footnote 2 Our article contributes to and further develops this debate by making visible interconnections between colonial spaces (colony/colony) and by unpacking the notion of ‘Europe’ itself. These interconnections, which have so far been underexamined, are investigated through the circulation of technologies of power, in our case mapping and the use of blank spaces on maps, across different colonial spaces.

According to Julian Go, ‘analytic bifurcation’ occurs due to the ‘tendency to conceptually slice or divide relations into categorical essences that are not in fact essences’.Footnote 3 For Go, analytic bifurcations are artificial and intertwined with issues of state-centrism, methodological nationalism, and Eurocentrism in historical sociology. State-centric thinking refers to the assumption that ‘social relations are contained by stated boundaries; and the related myth inherited from Westphalia that the world consists essentially of sovereign states.’Footnote 4 Methodological nationalism adds to this that national (or, in our case: regional) histories are treated as isolated from one another, whereby ‘knowledge of the world [is] discursively and institutionally prestructured in such a way as to obscure the role of exchange relationships.’Footnote 5 Eurocentrism, in turn, points to spatio-temporal hierarchies that separate ‘Europe’ from other spaces and situate it as being temporally ahead.Footnote 6 Taking all of this together, a narrative is created where European states become the ‘natural’ form of political organisation and are conceptualised as distinct and isolated from the rest of the world. Moreover, this has led to the tendency that other entities, such as metropole and colony, but also East and West, domestic and foreign, state and empire, or inside and outside, have become (artificially) separated as well.

The historical turn in International Relations (IR) and the global turn in History have addressed the problematique of analytic bifurcation by introducing connections and entanglements in the making of the international, which had been unexplored before.Footnote 7 Various authors and approaches underlined that developments, events, and issues, which were traditionally analysed as having solely happened in ‘Europe’, did not occur in isolation but rather through interactions with ‘non-Europe’.Footnote 8 This article contributes to the broader discussions on how to overcome analytic bifurcations as it highlights dyanmics of interconnectedness across colonial spaces and the Europe/non-Europe divide by exploring episodes of German colonial imaginaries and policies throughout the nineteenth century. For this purpose, we focus on mapping practices and how maps created imaginaries of imperial and colonial spaces and hence ‘colonisable land’ in both Africa and the European East. We build here on insights from the critical study of maps and mapping techniques and take maps not as perfect mirrors of a world out there.Footnote 9 Colonial spaces are not simply ‘found’. Often, maps rather create imaginaries of future political projects, by, for example, creating spaces as colonisable and hence conquerable. Our article traces how the cartographic ‘technicality’ of ‘blank spaces’ has been used in the German colonial discourse to create imaginaries of territories, which are colonisable for Germans, both in Africa and the European East.

We develop our argument in four sections. The first section outlines how approaches with a focus on connections and entanglements have been employed within IR so far. While these approaches have predominantly focused on metropole-colony connections, they have not (yet) sufficiently explored connections between colonial spaces. The purpose of this article is thus to extend previous scholarship by drawing attention to interconnections between colonial spaces. This helps us, in addition, to problematise the construction of the space of ‘Europe’ itself. Whereas it is common to take Europe as a unified whole – and thereby construct and reproduce the Europe/non-Europe bifurcation –, we break ‘Europe’ down and point to hierarchies – and the construction of colonial imaginaries – within Europe itself. To show the added value of these analytic redescriptions, we explore how technologies of power, in our case mapping and the use of ‘blank spaces’ on maps, were applied within the German colonial discourse to ‘colonial spaces’ outside of ‘Europe’, in particular Africa, and in the project of the ‘colonies of the East’, of which the Prussian Settlement Commission was part of. The second section, therefore, advances to study mapping as a specific technology of power in the imagination and creation of imperial and colonial spaces. Here we reconstruct how mapping and empire intersect and introduce the cartographic technique of designating ‘unknown’ areas as ‘blank spaces’. Yet, as we show, blank spaces do not only demarcate ‘unknown’ territories as they also create an imaginary of free and empty, colonisable land. The article focuses in the third and fourth section on two episodes of the use of blank spaces on maps in the context of the German colonial discourse. For this, we turn to cartographic products of the Justus Perthes publishing house in Gotha, the leading German-language publisher on cartography and mapping during the second half of the nineteenth and the first part of the twentieth centuries. The first episode encompasses imaginaries of exploration in the Humboldtian tradition and how these imaginaries depict areas outside of Europe, particularly in Africa, as blank spaces. The second episode reconstructs the cartographic work of Paul Langhans, who focused on mapping ‘Germandom’ (Deutschtum) in Central and Eastern Europe. Juxtaposing these two episodes shows the interconnectedness between these spaces (Africa and the European East) and how techniques such as blank spaces were applied to create colonisable land. Yet, this reconstruction foregrounds both similarities and differences in the politics of using ‘blank spaces’.

Moving beyond analytic bifurcations? The study of connections, entanglements, and the making of the international

The historical turn in IR has increasingly problematised narratives of the making of the international, which were primarily a consequence of analytic bifurcations, by invoking connections and entanglements.Footnote 10 This section will, firstly, present an overview of how connections and entanglements have been introduced and discussed within historical IR and, secondly, draw attention to two interrelated aspects that have not received sufficient attention: on the one hand, the connections between colonies rather than between metropole and colony and, on the other, the problematisation of the space of ‘Europe’.

One of the main impulses to study connections and entanglements comes from the approach of ‘connected histories’. It was Sanjay Subrahmanyam, a historian specialising in the early modern period, who developed the concept of ‘connected histories’ to problematise two aspects within the historiography of that period: methodological nationalism, which takes the European nation-state as a given and traces its emergence and history back in time, and the comparative method, which compares this development within different regions by conceptualising its entities as closed containers.Footnote 11 Subrahmanyam argues, instead, that it is necessary to ‘delink the notion of “modernity” from a particular European trajectory’ since there was a ‘more-or-less global shift, with many different sources and roots, and – inevitably – many different forms and meanings depending on which society we look at it from’.Footnote 12 According to him, the connected histories approach aims to ‘not only compare from within our boxes, but spend some time and effort to transcend them, not by comparison alone but by seeking out the at times fragile threads that connected the globe’.Footnote 13 Subrahmanyam thereby underscores the need to think beyond the analytic categories and boxes that result in methodological nationalism concealing connections. Whereas Subrahmanyam focuses on the early modern period, Gurminder Bhambra has taken up the discussion on connected histories to study modernity.Footnote 14 Bhambra argues that modernity was ‘formed in and through the colonial relationship’ and as such the ‘colonial question needs to be considered as integral to the development of the nation-state not just outside Europe, but within Europe as well’.Footnote 15 A second approach that explores the relevance of connections and entanglements to understand the making of the international and that has figured prominently in IR is global history.Footnote 16 According to Sebastian Conrad, global historical scholarship criticises tendencies of internalism and Eurocentrism in the social sciences and humanities. It, instead, ‘takes the interconnected world as its point of departure, and the circulation and exchange of things, people, ideas and institutions … among its key subjects’.Footnote 17 For example, for the context of German colonialism, Andrew Zimmermann, in his book Alabama in Africa, traces the entanglements between the American South, the German Empire and Togoland through an account of the Tuskegee cotton expedition to Togo in 1901. He tells the story of not only how the American South became a model for European colonial rule in Africa but also how the expeditions, which were organised for the exchange of knowledge, also influenced discussions on agricultural labour within Germany. Zimmermann concludes that the ‘Tuskegee expedition to Togo sits at the junction of three great transformations, linking the racial political economies of the southern United States, eastern Germany, and colonial Africa’.Footnote 18 Thereby, Alabama in Africa makes visible a variety of different entanglements, which became hidden if one traces events and developments within bounded entities.

These formulations have in common that they problematise the bifurcations of metropole/colony and state/empire. This insight has also been addressed in IR, where several recent contributions in the context of the historical turn have demonstrated how a series of developments, which were previously studied in isolation within the designated space of Europe, were in fact made possible through interactions with spaces outside of it. Some have shown how the metropole/colony and nation-state/empire bifurcations silenced a series of connections.Footnote 19 Others, in turn, have underlined how the story of sovereignty, the meaning of Westphalia, and the expansion of the international society cannot be attributed to Europe alone but need to be considered as developments that happened in interaction with spaces outside of Europe.Footnote 20 One of the main foci of the historical turn in IR has been to analyse connections, exchanges, and dialogues, which had previously been made invisible by analytically separating state/empire and metropole/colony. Despite their centrality, it is important to emphasise, however, that state/empire and metropole/colony are not the only bifurcations at stake.

As Go points out, the ‘tendency to conceptually slice and divide relations into categorical essences that are not in fact essences’ is not limited to the metropole/colony bifurcation but it is also at stake in how ‘East’ from ‘West’, ‘Europe’ from the ‘Rest’, the ‘inside’ of nations from their ‘outside’, or ‘the domestic’ from the ‘foreign’ becomes divided.Footnote 21 The predominant focus on the metropole/colony bifurcation can also work to make other hierarchies and dynamics invisible in the narrative of the making of the international. This has been problematised by different scholars. For example, George Steinmetz focuses on the colonial state as an analytical field and thereby makes visible the different models of governance implemented in German colonies. Drawing on Bourdieusian field analysis, Steinmetz argues that these different modes of governance were in place as ‘the colonial state field autonomized itself from the central state and from the European colonial field of power and developed its own self-referential struggles and specific forms of symbolic capital.’Footnote 22 Hence, this account shows how different hierarchies and policies were implemented within the German Empire and thereby foregrounds a dynamic that might be overlooked at times if the metropole is taken as a bounded space only interacting with the colony rather than the autonomy of the colonial state. Furthermore, making present connections and entanglements, which were previously absented from the narrative of the making of the international continues at times to reproduce the linear progressive narrative of the making of the international.Footnote 23 To further elaborate on different hierarchical processes it is crucial, however, to problematise other analytic bifurcations. In this respect, another important bifurcation that has been scrutinised is the colony/colony one, whereby the connections, exchanges, and dialogues between different colonies become invisible. For example, the literature on ‘imperial policing’ has shown that policing was ‘part of a single system – bounded by shared institutions and common expectations’ and as such ‘the empire was a system in which ideas flowed not only outward from the metropole and back again but between the colonies themselves.’Footnote 24 In a similar vein, Robbie Shilliam has problematised the bifurcation that prevents us from seeing connections between the colonised (i.e., colony/colony connections).Footnote 25 For him, this is due to the ‘cartographic gaze’ whereby the ‘peripheral figures, especially the colonised among them, can only understand themselves in mute relation to the imperial centre.’Footnote 26 Shilliam thus underscores how Europe continues to be the centre that we refer to or connect back to. This might result in overlooking colony/colony connections that did not revolve around Europe as its centre.

While these contributions have been important in complicating the narratives of the metropole/colony and colony/colony connections, we expand this further as we problematise ‘Europe’ itself by showing how technologies of power developed to produce colonial imaginaries and control colonies were applied to Africa and the ‘colonies in the East’. The way Europe is taken as a unified space is part of why the German colonial expansion outside of Europe (by means of ‘protectorates’) and the establishment of German expansionist policies and imaginaries towards the East of Europe are not analysed as connected events: taking Europe as a unified space does not allow us to examine the existent hierarchies within Europe. The construction of the space of Europe can be problematised, and thereby decentred, in two main ways. First, one can excavate the different hierarchies that permeate the space that is designated as ‘Europe’. For example, it has been discussed how regions and peripherality were constituted in the Balkans and Eastern Europe historically.Footnote 27 As Larry Wolff states, ‘Eastern Europe’ was constructed as a site of ‘inclusion and exclusion, Europe but not Europe. Eastern Europe defined Western Europe by contrast, as the Orient defined the Occident, but was also made to mediate between Europe and the Orient.’Footnote 28 The construction of these spaces by assigning spatio-temporal hierarchies – outside of Europe/behind of Europe – constituted a ‘nested Orientalism’ within the space designated as Europe whereby the binaries of West/East and modern/traditional continued to be narrated and reproduced.Footnote 29 Within the German political discourse, this led to the creation of a specific ‘German myth of the East’. Since the beginning of the nineteenth century, and well before German unification in 1871, ‘Germans have so often seen Eastern Europe at one and the same time as both a dirty “Wild East” marked by chaos and disorganization, and yet also as a land of tremendous future possibilities and potential for Germans.’Footnote 30 The imaginary of a German frontier zone revolved mainly around the eastern borderlands of Prussia and its provinces of East Prussia, West Prussia, Silesia, Posen, and Pomerania.Footnote 31

The second and interrelated direction to problematise ‘Europe’ has been by bringing in postcolonial and decolonial perspectives to study Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans.Footnote 32 Several contributions have focused on the ‘coloniality of power’ and analysed spaces such as the European East by underlining that along with the colonial difference, there was also the imperial difference which was ‘less overtly racial, more pronounced ethnic, and distinct class hierarchies’ underlying the relationship between the ‘European empires and their (former) subjects’.Footnote 33 The ‘double imperial difference’ created ‘an external difference between the new capitalist core and the existing traditional empires of Islamic and Eastern Christian faith – the Ottoman and the Tsarist one’ and an ‘internal difference between the new and the old capitalist core, mainly England vs. Spain’.Footnote 34 As Walter Mignolo elaborates, ‘the imperial external difference created the conditions for the emergence, in the eighteenth century, of Orientalism, while the imperial internal difference ended up in the imaginary and political construction of the South of Europe. Russia remained outside the sphere of Orientalism and at the opposed end, in relation to Spain as paradigmatic example of the South of Europe’.Footnote 35 Extending on Mignolo’s distinction, Manuela Boatcă argues that there were three Europes: decadent Europe, heroic Europe and epigonal Europe. According to Boatcă, decadent Europe ‘had lost both the hegemony and, accordingly, the epistemic power of defining a hegemonic Self and its subaltern Others’, heroic Europe was defined as ‘the producer of modernity’s main achievements’ and epigonal Europe ‘defined via its alleged lack of these achievements and hence as a mere re-producer of the stages covered by the heroic Europe’.Footnote 36 This relationship meant that heroic Europe deployed ‘its imperial projects in the remaining Europes or through them’ through two mechanisms. Firstly, heroic Europe used ‘the gains of the first, Spanish-Lusitanian modernity to derive the human, economic and cultural resources that substantiated the most characteristically modern achievement’ without integrating the ‘contributions of either the decadent European South or of the colonised Americas in the narrative of modernity’.Footnote 37 The second mechanism was the establishment of ‘neocolonies in the rural and agricultural societies of the region’ which worked to institute a set of relationships of underlying blurredness – ‘being the West’s partial Other and its incomplete self’.Footnote 38 As such, the space of ‘Europe’, which is separated from other spaces and temporally ahead, is that of heroic Europe.

A focus on these two interrelated dynamics of, on the one hand, historicising the (processes of) construction of the space of Central and Eastern Europe and the Balkans and, on the other hand, foregrounding hierarchies between different ‘Europes’ through postcolonial and decolonial perspectives has been gaining some attention in different academic contexts.Footnote 39 In this article, we further develop discussions with respect to these two dynamics by focusing on how the construction of the spaces of heroic Europe and epigonal Europe needs to be further problematised in order to move beyond the analytic bifurcation of Europe/non-Europe. The problematisation of the separation of Europe/non-Europe will be done by underlining two dynamics: firstly, problematising the construction of the space of ‘Europe’ and, secondly, ‘connecting’ different colonial spaces that had been separated because of the Europe/non-Europe divide. We do this by discussing imaginaries of German colonialism and how they construct Central and Eastern Europe as a colonial space. The divisions and hierarchies were part of the imaginaries of heroic Europe. As such, it was heroic Europe that produced decadent and epigonal Europe (other), and thereby heroic Europe (self). Moreover, focusing on German colonial imaginaries shows that Germany’s own place within heroic Europe was not stable. Boatcă’s initial classification is organised around ideal types of (quasi-)Europes: Spain and Portugal represent decadent Europe, France and England heroic Europe, and the Balkans epigonal Europe. Germany, though, is missing in the list of ideal types. The reason for this is the instability of its position: at first being in-between epigonal Europe and heroic Europe and later trying ‘moving into’ heroic Europe when it started to solidify itself within European hierarchies.

Influenced by postcolonial perspectives and global history, studies on German colonialism gained some momentum recently.Footnote 40 Firstly, these contributions have focused on making German colonialism more present in the literature. Secondly, they have underlined how the making of ‘Germany’ cannot be told separately from its colonial endeavours, and vice versa. Conrad argues that Germany and its colonies should not be treated as separate but rather be approached as a ‘single analytical field’.Footnote 41 Furthermore, he points to the ‘need to move beyond colonialism as happening only in Africa and Asia’.Footnote 42 For Conrad, ‘territorial acquisitions overseas and in Eastern Europe operated within a shared paradigm’ whereby ‘the German notion of Poland was gradually transformed and, increasingly reconfigured within national and, soon also, colonial parameters’.Footnote 43 To further problematise the separation of ‘Europe’ and ‘non-Europe’ that makes connections invisible, we focus in this article on a specific form of colonial and imperial space making, namely blank spaces on maps, and how this technique was employed in German mapping projects to designate potential ‘colonies in the south’ and ‘colonies in the East’ as colonial wasteland. The following section will, thus, discuss the construction of imperial and colonial spaces in general and then turn to the specific cartographical technicality of blank spaces in nineteenth-century maps.

Empire, mapping, and the production of blank spaces

Building on contributions from critical geography and cartography, maps and mapping techniques, such as blank spaces, have received increasing attention within IR.Footnote 44 According to this strand of research, mapping is part of the making of the international, often intertwined with colonial and imperial projects. As Matthew H. Edney states, ‘[i]mperialism and mapmaking intersect in the most basic manner. Both are concerned with territory and knowledge.’Footnote 45 According to Edney, imperial mapping is ‘constructed through cartographic discourse that represent a territory for the benefit of one group but that exclude the inhabitants of the territories represented’.Footnote 46 In this section, we reconstruct scholarship on mapping and its relationship to imperialism, and point to the importance of the technique of blank spaces in this process.

The ‘post-representational turn’Footnote 47 in the study of maps and mapping departs from the ‘ideal of cartography’Footnote 48 and its belief that maps mirror the world ‘out there’. This strand of scholarship highlights three points. First, maps are not understood as perfect mirrors of a reality ‘out there’ anymore but, in the words of J. B. Harley, ‘performative’.Footnote 49 For Harley, maps shape our imagination and create conditions of possibility of rule and domination: ‘maps anticipate empire’.Footnote 50 They are important for the imagination, organisation, and execution of colonial projects. Second, mapping is never a fully stable and concluded process, as maps circulate and are permanently (re)interpreted.Footnote 51 Similarly, colonial projects are never entirely stable; they are always in the making and in need of stabilisation through technologies of power such as maps. Third, maps and mapping appear as technical exercises and, hence, apolitical. However, it is important to understand the politics of technicalities involved. Maps and mapping techniques – technicalities of cartography – need to be seen as central aspects of the negotiation in projects of exploration, conquest, and colonisation. Technicalities render political projects ‘scientific’. In this article, we analyse one specific technicality of mapping, namely the production of blank spaces.

Blank spaces figure in modern maps to delineate ‘unknown’ territories. According to Harley, ‘there is no such thing as an empty space on a map’.Footnote 52 Instead, Harley argues, ‘blank spaces’ or (‘silences’, as he prefers to call them) are ‘positive statements’ and not ‘merely passive gaps in the flow of language’: they are ‘active human performances’.Footnote 53 Blank spaces are a particular feature of modern maps. In European medieval maps, blank spaces were used, as Alfred Hiatt explains, to depict ‘the land that was rather a product of hypothesis rather than exploration’; in later periods, these blank spaces were replaced with longer texts or ‘pseudo-topography’ such as ‘speculative mountain ranges, vegetation and rivers’.Footnote 54 It was in 1749, when, as Siobhan Carroll puts it, ‘Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville erased the world.’Footnote 55 In a map of Africa, d’Anville had reintroduced the technique of blank spaces in order to depict ‘unknown’ territories. Finally, by the ‘mid-nineteenth century the blank interior of Africa – marked, if at all, with captions such as “unexplored”, “unknown interior”, “unexplored by Europeans” – was a fairly standard feature of maps of the continent’.Footnote 56 By this time, blank spaces figured prominently on maps of Africa, Australia, and the Polar regions.

Conceptually, blank spaces help create the modern, enlightenment-driven, ‘ideal of cartography’, that is, that maps objectively depict the world.Footnote 57 In this imaginary, politics and science are constructed as separate realms, where maps appear as neutral.Footnote 58 Moreover, in line with (and reinforcing) the ‘empiricist’ worldview of the nineteenth century, blank spaces create the impression that those parts on a map, which are filled with, for example, topographical details, are composed of objective, scientific, and accurate knowledge. This entails that they become validated, meaning what is depicted must be true; nothing speculative or fictitious, it seems, can be on a map as ‘unknown’ territories are marked as ‘blank’ or ‘empty’; either something is known, or it is unknown; tertium non datur.Footnote 59 Furthermore, these blank spaces on maps were vital in creating imaginaries of exploration and thereby attracting travellers, hunters, missionaries, and explorers, all aiming to extinguish the ‘horror vacui’ on maps. However, following Harley, blank spaces do not only demarcate unknown territories. They also create an imaginary and a ‘promise of free and apparently virgin land – an empty space for Europeans to partition and fill’.Footnote 60 Blank spaces designate colonial wasteland. Thereby, the landscape becomes ‘de-socialize’Footnote 61 and even ‘de-humanized’.Footnote 62 In this respect, blank spaces resemble other technologies in the justification of empire and the delineation of ‘no-man’s land’, particularly the concept of terra nullius as the absence of possession in international law, which gained prominence from the late nineteenth century onwards.Footnote 63

This article focuses on the production and circulation of blank spaces on maps and how this technique has figured as an important part of the imperial project. Within the field of IR, Jordan Branch emphasised the link of maps and empire by suggesting the concept of colonial reflection. This term describes the ‘reflection of techniques used first in colonial areas onto European internal political arrangements’.Footnote 64 Branch, thereby, addresses the analytic bifurcation of Europe/non-Europe and highlights how techniques used in colonial spaces were then transferred to Europe, thus underlining the circulation and connection rather than separation. In this article, we intend to further advance this discussion by focusing on how techniques circulated through colonial spaces that were perceived as being separate because of the division of Europe/non-Europe.

For this purpose, we introduce in the next section archival material of the mapmaking activities and writings of cartographers at the Justus Perthes press in Gotha. Between the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth centuries, Justus Perthes figured as the leading German-language publisher when it came to the collection, evaluation, and distribution of geographical knowledge and expertise. It became recognised for its production of maps of both European and non-European territories. As we argue, some of the cartographic work at Perthes needs to be seen in connection with the German colonial movements – sometimes as a reflection of it, sometimes as a driving force. We are interested in how cartographers connected in their imaginaries, by using the mapping technique of blank spaces, European and non-European territories as (potential) colonial and imperial spaces. We focus, therefore, on two episodes and their related projects. First, we reconstruct attempts to map and explore territories depicted as blank spaces in the interior of Africa since the mid-nineteenth century. This project, even though presented as being driven by ‘scientific’ interest in the exploration of ‘unknown’ territories, was intertwined with a specific politics of knowledge as it helped create an imaginary of what counted as ‘unoccupied’ land. This construction also served to identify spaces that the future Kaiserreich might take possession of after its unification and, thereby, ‘catch up’ with other European powers in their colonial expansion of territories outside of Europe. Second, we reconstruct a project that emerged during the last decade of the nineteenth century and used a colonial imaginary for Europe – and here the East of Europe – itself. Here we trace the work of Paul Langhans, one of the leading cartographers at Perthes, and the way he designed, executed, and edited the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas (German Colonial Atlas) between 1893 and 1897. As Langhans was also part of the völkische Bewegung, the leading ethnic-nationalist movement in Germany, and devoted his work to find traces of Deutschtum (Germandom) around the world, the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas was not restricted to German colonies outside of Europe but also dealt considerably with Germandom in the East of Europe. This imaginary uses blanks spaces to construct ‘unoccupied’ territories for German settlement and colonisation in the East of Europe by ‘emptying out’ these spaces of its population.

From ‘unknown land’ to ‘No Man’s Land’: The use of blank spaces in Africa

Founded in 1785 by Johann Georg Justus Perthes (1749–1816) in Gotha, the Justus Perthes publishing house developed into one of the most significant European cartographic presses within a few decades.Footnote 65 While early publications included the court almanac of Gotha and a famous necrology, the Justus Perthes press began from 1815 onwards to specialise in scientific maps and atlases and, consequently, changed its official name into Justus Perthes’ Geographische Anstalt (Justus Perthes’ Geographical Institute). Along with geographical societies, such as the Royal Geographical Society in Britain,Footnote 66 private geographical firms, such as Murray in Britain, Hachette in France, or Perthes in Germany, developed during the nineteenth century not only into important sites for the publication of geographical products but played a significant role in the collection and production of geographical knowledge itself. As the academic discipline of geography was only in an early stage of development, these private initiatives acted as centres of geography.Footnote 67 Private cartographic publishers started, for instance, to organise explorations to non-European territories, often intertwined with colonial imaginaries, aspirations, and enterprises.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, Justus Perthes became widely recognised for its production of atlases. Atlases, which often came in the format of convenient hand atlases, were among the most popular geographical products. They were affordable for a growing educated middle class interested in geography, guided private, or state-run expeditions, and documented ‘scientific progress’. Additionally, atlases had the advantage that they were produced in subsequent instalments, which made it possible to adapt them relatively quickly in the event of new ‘discoveries’. The production of the Stielers Hand-Atlas in 1816, edited initially by the cartographer and administrator Adolf Stieler (1775–1836), became the first significant cartographic success of the publishing house and ‘provided the basis for the nineteenth-century atlas concept [as it] became the longest-lived, the most well-known and above all the most successful German hand-atlas of the nineteenth century’.Footnote 68 Typical for this atlas was that it left those parts of the world, of which Europeans only had incomplete and fragmented knowledge, as blank spaces. The distinction between what is ‘known’ and the ‘unknown’ of blank spaces was further increased as ‘known’ areas were depicted as detailed as possible. This had the effect that maps often appeared as cluttered and were difficult to read. The blank spaces of these maps encompassed large areas outside Europe, such as in the Polar regions, Australia and, in particular, the interior of Africa (Figure 1). By publishing its maps in several instalments and subsequent editions, Stielers Hand-Atlas created an imaginary of ‘cartographic progress’ and triggered an ethos of discovery as the blank spaces on the map began to ‘shrink’ from edition to edition.Footnote 69

Figure 1. Map of Africa in Stielers Hand-Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1820).

Importantly, however, knowledge on maps was much more precarious, as the imaginary of scientific accuracy and objectivity claims. It was often rather an illusion. For instance, maps of Africa in the Stielers Hand-Atlas feature, as many other nineteenth-century maps, an extensive mountain range called the Mountains of Kong. These mountains start in Western Africa, in the highlands of Guinea, and extend along 10 degrees of latitude into the interior of Africa. The Mountains of the Kongo played an important role in explaining two phenomena: on the one hand, the direction of drainage of large African rivers and, on the other hand, the question of why there was no commercial exchange between Africa’s coastal and interior regions. Although these mountains were included in numerous European maps and became influential in depicting Africa and produced several hypotheses about the African continent (such as trade and climate), they were eventually imaginary mountains: the Mountains of Kong never existed. This, however, was revealed in the 1890s only. The episode of these imaginary mountains shows the authority of maps and their worldmaking capacity. And, it points to the question of authoritative knowledge for maps, and the hierarchies and politics of knowledge involved. European mapmakers of the nineteenth century based their knowledge on a few, often precarious, sources of European travellers or even on authors from antiquity. Non-European sources were usually not included. In other words, speculation was possible in these seemingly objective and scientific maps, but only if it would fit the Europeans’ gaze of Africa.Footnote 70

While the Justus Perthes publishing house obtained information in its initial phase by acquiring maps from competitors or directly from explorers, this changed from the mid-nineteenth century onwards as the press transformed itself into a genuine ‘center of calculation’Footnote 71 and began to organise its own explorations. This development is closely associated with the cartographer August Petermann (1822–78). Petermann’s trajectory is a good example of metropole/metropole connections and how the Enlightenment-driven ‘ideal of cartography’ circulated and expanded within Europe. Petermann was trained by Heinrich Berghaus, who published in close cooperation with Alexander von Humboldt, based on Humboldt’s magnum opus Koinos, the Physikalischer Atlas (Physical Atlas) with Justus Perthes. Petermann emigrated in the 1940s first to Edinburgh, where he prepared the English translation of the Physikalischer Atlas with the influential cartographic publisher W. and A. K. Johnston, and moved later to London, where he established himself as a well-known independent geographer and cartographer, became a member of the Royal Geographical Society, was awarded the honorary title of a Physical Geographer to the Queen, and created a network with several explorers. Petermann joined Justus Perthes in 1854 and established his own geographical journal, Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (Petermann’s Geographical Messages), one year later. By mobilising his network, the Mitteilungen became one of the leading European outlets for the study of geography and held this status for nearly a century.Footnote 72 One of the innovations of the journal was its map-oriented approach. As Petermann explained, ‘[t]he end result and the final goal of all geographical research, exploration, and surveying is, first of all, the depiction of the surface of the earth: the map.’Footnote 73 Moreover, according to Petermann, the primary mission of geography was to fill in the last ‘blank spaces’ on maps.

For this purpose, Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen attempted to include the newest available information in each issue. It published, for example, letters of Alexander von Humboldt or travelogues of famous explorers such as David Livingstone and Heinrich Barth, for which the journal acquired exclusive publishing rights (at least for the German-speaking market). In addition, by means of the journal, Petermann started to organise and fund his own expeditions to explore unknown areas and tied this to a still rather vague colonial imaginary. Readers of the Mitteilungen could follow the trajectory of these missions from issue to issue. The first significant expedition organised by Petermann was the so-called German Inner-Africa Expedition (Deutsche Inner-Afrika Expedition) between 1860 and 1863. Figure 2 displays a map created for this mission, which was part of the instructions the members of the expedition received before their departure and which includes several travel routes. The goal of the expedition was to explore the ‘mythical’ Wadai Empire, which is portrayed as blank on the map and was considered ‘untouched’ by Europeans. Although the German Inner-Africa Expedition ended tragically, with most of its members dying during the mission, Petermann considered it a success as it had shown that the areas it started to explore ‘deserve a special interest; they are not deadly African swamps or sandy deserts that would deserve to be visited only every 100 years by a geographical traveller, but areas that have a history and a purpose, … and which are an El Dorado when it comes to their nature’.Footnote 74 Despite these ‘favourable natural conditions, these areas are a kind of “no man’s land” to which any European power could extend its hand’.Footnote 75

Figure 2. Map of Africa including itineraries for the ‘German Inner-Africa Expedition’, Justus Perthes Gotha (1860).

By organising expeditions and using precise cartographic techniques, Petermann created a scientific imaginary that claimed to depict the world objectively and constructed politics and science as separate. However, the use of the specific technique of ‘blank spaces’ is embedded in the wider politics of creating potential imperial and colonial spaces. ‘Blank spaces’ create the idea of ‘empty space’ – empty in terms of rival (European) territorial claims, yet full of natural resources – which could be filled by future colonial projects. This also has significant repercussions for the connection between a – still imaginary – metropole and – still imaginary – colonies. Taking place a decade before the German unification of 1871, Petermann saw in the expedition an opportunity to bring together voices that intended to overcome the particularism of the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund) and advocate instead a German nation-state. As such, the Mitteilungen launched a public fundraising campaign asking each of the several sovereigns of the Confederation to donate to the development of ‘German science’ and thereby contribute to the larger ‘German empire’. For Petermann, Germany could only become a true state if it acquired colonies. As such, the imaginative nation was an official German state, holding official state-run colonies. This also has repercussions for the well-established separation between empire and nation, where the former develops into the latter, as the case of Germany shows that empire building and nation building are ‘not two stages of a consecutive development, but rather were dependent on each other’.Footnote 76 Taken together, the German Inner-Africa Expedition can be read as an initial attempt to find an ‘empty space’ for future German colonisation.Footnote 77

‘Scientific’ enterprises, such as Petermann’s German Inner-Africa Expedition, created proto-colonial imaginaries at the eve of German unification in 1871. While these aspirations were not further pursued in the initial phase of the Kaiserreich, the German colonial policy began to shift from the mid-1880s onwards with Chancellor Bismarck organising the Berlin Conference in 1884/5, the acquisition of German overseas colonies in the same year, and Wilhelm II, who became emperor in 1888, adopting the imperial foreign policy of Weltpolitik (world politics). Yet, by this period, the search for colonial territory was more complicated than initially expected, and Germany had difficulties finding its own ‘spot under the sun’. Much of what was depicted as ‘blank space’ on maps in previous decades had been explored and taken into possession by other colonial powers in the meantime. In the next section, we reconstruct a colonial project, which centred around an imaginary of the ‘colonies in the east’, that is, located within Europe and here mainly in what it refers to as the ‘Slavic’ countries.

Mapping Pan-German colonial imaginaries: The ‘colonies in the East’

The Justus Perthes press published between 1893 and 1897, in 15 instalments, one of the first atlases dedicated to the newly established German colonial empire: the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas (German Colonial Atlas) was designed and edited by Paul Langhans (1867–1952), a young cartographer and demographer who had joined Perthes in 1889.Footnote 78 Within a few years, Langhans became ‘the most important representative of ethnocentric geography’Footnote 79 in Germany and figured as the ‘doyen of German-nationalist cartography’.Footnote 80 Langhans was a member of several far-right organisations, including the Pan-German League. He had studied Geography in Leipzig, where he was influenced by Friedrich Ratzel and his idea of Lebensraum (‘living space’). In the decades around 1900, Langhans further radicalised a population-based vision of Lebensraum geopolitics by ‘translating’ the völkische ideology of the Pan-German League into cartographic projects.Footnote 81

The Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas is compiled of more than thirty main maps, supplemented by several small auxiliary maps. Two characteristics of these maps stand out. First, the atlas includes mainly topographical maps for most colonies but hardly portrays any topographical detail for areas that are considered to have a larger ‘German’ population. For these areas, it focuses almost exclusively on thematic maps, some of which depict economic and trade issues, but most are ethnographic maps. Nonetheless, these maps still follow the tradition of Justus Perthes in designing very detailed maps to create a scientific imaginary – this time of mapping ethnographic entities. Second, and contrary to what one would expect of an atlas of the German colonial endeavour at the end of the nineteenth century, the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas is not limited to German colonies outside of Europe. While it features, on the one hand, official colonies in Africa, Asia, and Oceania, which had been acquired by Germany in the previous decade following the ‘standard European colonial convention’ and thereby ‘resembled those [atlases] of other European powers’, Langhans’s atlas contains, on the other, ‘significant anomalies’:Footnote 82 it starts in Europe and constructs the European East as a colonial space in its own.

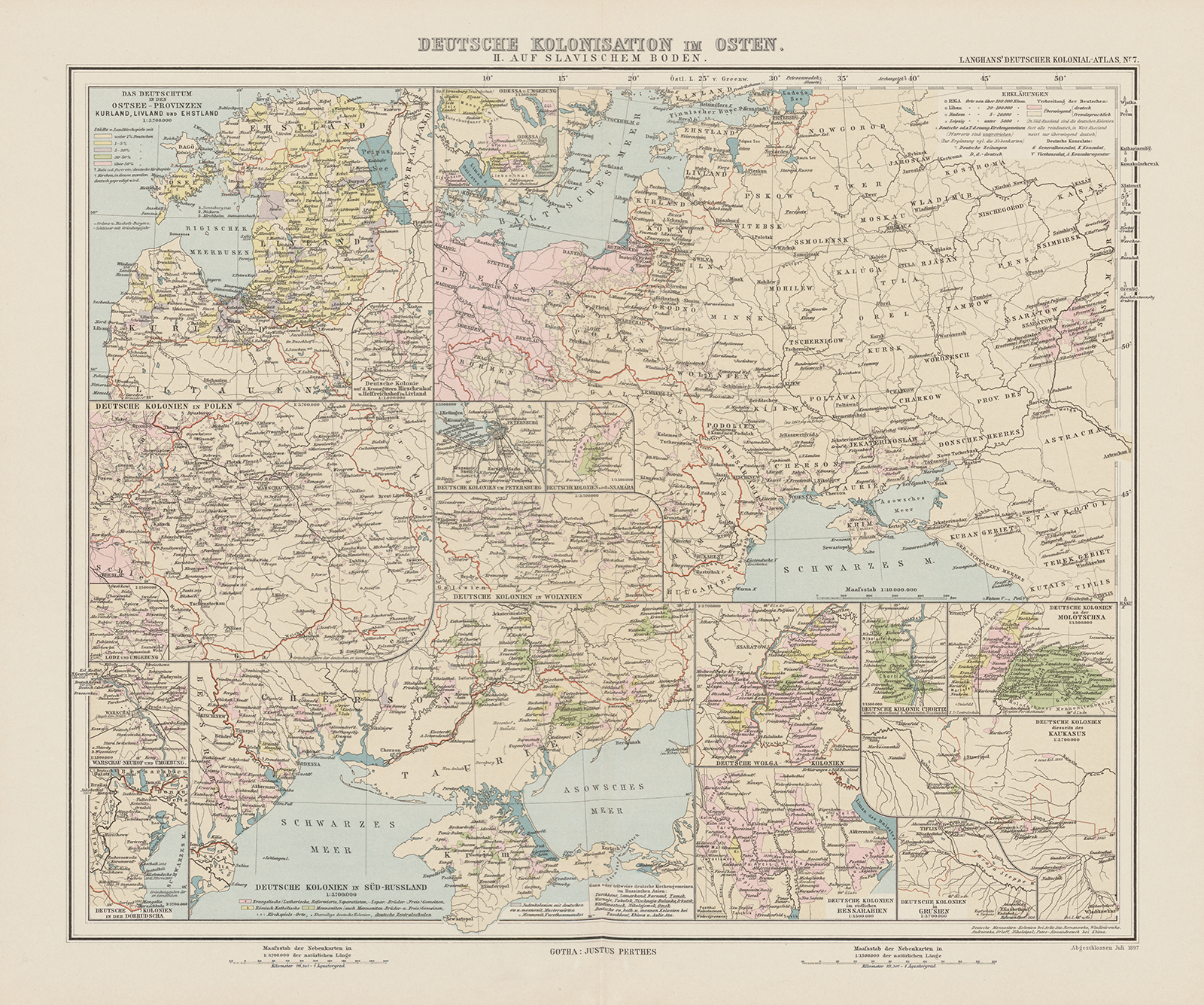

As such, the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas includes several maps claiming to portray the ‘German Colonisation in the East’ (‘Deutsche Kolonisation im Osten’). For example, one of these maps is concerned with the German colonisation ‘On Slavic soil’ (Figure 3). The main map is surrounded by various auxiliary maps, which carry titles such as the ‘German Colonies in Poland’ (‘Deutsche Kolonien in Polen’), ‘German Colonies in South Russia’ (‘Deutsche Kolonien in Südrussland’), or ‘German Wolga-Colonies’ (‘Deutsche Wolga-Kolonien’). Some of these maps seem to depict contemporary German ‘colonial’ enterprises, while others are designed as historical maps.

Figure 3. Map of ‘German Colonisation in the East. On Slavic Soil’, in Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1893–1897).

Langhans justifies the unconventional composition of the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas in an introduction, which was added to the final instalment. The tone of the introduction is overall expansionist and völkisch-nationalist, and includes a significant redefinition and ‘enormous broadening’ of the concept of ‘colonialism’ itself.Footnote 83 As Langhans writes, the ‘recent turn to the acquisition of official colonies by the German Reich through overseas protectorates has one-sided the use of the concept of the colony so much, namely in favour of the idea of the state-colony, that it might be bold to give the name colonial atlas to all settlements of Germandom’.Footnote 84 It is through the notion of Germandom (Deutschtum) that Langhans redefines the concept of colonialism. For Langhans, the German colonial enterprise is divided into two separated colonial projects: one driven by the state and one by the Volk. While the former has been realised through the acquisition of ‘protectorates’ by the Kaiserreich and is located outside of Europe, the latter involves a more ‘hidden’ colonial project, namely the project of Germandom that is driven by a mythical Volk. The Volk, as an ethnic marker, is distinguished from modern and traditional notions of both state and nation.Footnote 85 It existed before German unification and can ‘survive’ outside of the boundaries of the state. This also becomes visible in the map of German colonisation ‘On Slavic Soil’ (Figure 3). Pink-coloured areas, which indicate German settlements, dominate the map. There is no clear demarcation of the eastern border to Prussia. Moreover, the fact that the border of the Kaiserreich does not overlap with German settlement ‘leave[s] the impression that the territory formally under German rule was not congruent with the German territory, defined as the space settled and thus claimed by the German people’.Footnote 86 It gives the illusion of an open frontier space in the East of Europe.

Langhans’s colonial project of the German Volk predates the Kaiserreich, and it is a particular historical narrative plotted to justify German colonial settlements in the East. As Langhans claims, ‘today’s colonial policy of the German Reich is nothing abruptly new, but … it is necessary to understand this in line with and the context of the century-long colonial activity of the Germans.’Footnote 87 Thus, according to Langhans, Germans were involved in colonial activities before the German unification of 1871. In this narrative, Germany is neither new nor late in its colonial acquisitions. These earlier activities remained, however, unnoticed as they were not necessarily tied to the official colonial project of a state. In order to colonise, Germans do not need a state; the Volk is enough. Contemporary colonialism is legitimised by framing migration movements of the past as colonial activities and thereby producing a historically grown and established German colonial identity.Footnote 88

By invoking the historical myth of century-long colonial activities, Langhans also shifts the space of colonisation. While the conventional use of colonialism was limited to territories outside of Europe, the new focus on ‘Germandom’ makes it possible to locate German colonies, and the claims and aspirations for German future colonial activities, within Europe itself. These colonial activities do not occur in a void of ‘population-free territory’, but colonisation is regarded as a recurring struggle between different ethnic entities. As explained in the introduction of the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas:

Apart from the Reich-German protectorates, those countries are most intensively examined, which have proven to be the most beneficial for the settlement activities of German migrants and in which Germandom could relatively preserve its independence against foreign influences: the German agricultural colonies. Arduous conquest and the settlement policy of the Guelphs, the Ascanians, the Hohenzollerns and also the Habsburgs, as well as the Teutonic Order towards the east, did Germanise the lands between Elbe and Vistula and large areas of the Hungarian lands and mountain ranges.Footnote 89

The Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas follows in its maps and introduction a certain narrative of the European East, which had been established in the German-speaking territories during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and which portrays Central and Eastern Europe as different, namely as less ‘ordered’ and in a permanent state of turmoil. This ‘East’ is a frontier space and a ‘Wild East’.Footnote 90 Langhans understands the ‘Wild East’ as a conflict zone between Germans and Slavs, and frames it, as other völkisch thinkers, through ‘a proliferation of water metaphors’,Footnote 91 where German agricultural colonisation of the soil is presented as a ‘fortress’ and ‘dam’ against the danger of a ‘Slavic flood’. Central and Eastern Europe is constructed as a colonial space. As a ‘Wild East’, it needs colonial intervention to establish order, and it is the destiny of the German Volk, due to its ‘century-long colonial activity’, to do so by providing ‘culture’.Footnote 92 This justifies for Langhans an aggressive and imperialist expansion of Germandom in the future.Footnote 93

Although Langhans addressed in the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas mainly ‘colonial’ activities ‘beyond’ the German state, he considered the state-organised Royal Prussian Settlement Commission of 1886 a step in the right direction. The Commission continued a longer tradition of Prussian imperialism, particularly towards Poland, which was initiated by the First Partition of Poloand in 1772 and later also entailed population policies.Footnote 94 While the Prussian authorities insisted first on a policy of coexistence between German- and Polish-speaking populations, the Commission replaced this with a more aggressive settlement policy, which included the settlement of (Protestant) German-speaking farmers in (Catholic) Polish-speaking areas.

After completing the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas, Langhans published various maps, using different publication platforms of Justus Perthes, in which he documented the ‘progress’ of the Prussian Settlement Commission. Blank spaces play a central role in these maps. In 1896, for example, Langhans included a map in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, for which he had obtained exclusive information from the Royal Prussian Settlement Commission (Figure 4). The map aims, as Langhans writes in a short description, to display the ‘success of modern state colonisation in the East of Prussia’.Footnote 95 It depicts German-speaking areas from before 1890 as red and acquisitions of the Settlement Commission as green. Territories with a Polish-speaking majority are white, that is, depicted as blank space. ‘As the Polish territory remains white’, Langhans explains, ‘it is possible to insert new acquisitions.’Footnote 96 This is a significant reformulation of the relationship between blank spaces and the depiction of cartographic progress in two ways. First, while blank spaces were used in previous maps of areas outside of Europe to depict territories and populations ‘unknown’ to Europeans, Langhans uses blank spaces in territories ‘known’ to Europeans. Second, the ordinary reader is invited to become an active participant in this colonial movement by simply using pen and pencil.

Figure 4. Map of ‘The Work of the Prussian Settlement Commission in the Provinces of Western Prussia and Posen, 1866–1896’, Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (1896).

Blank spaces and similar cartographic techniques were also pivotal in another large atlas project of Langhans, the All-Deutscher Atlas (Pan-German Atlas), which was published in 1900 and is directly tied to the leading organisation of the völkische Bewegung, the Pan-German League.Footnote 97 The first map of this atlas is intended to provide an overview of the worldwide spread and distribution of ‘Germandom’ (Figure 5). The map is accompanied by two small auxiliary maps, one on the worldwide distribution of land between countries (Figure 6) and the other on the worldwide distribution of population between countries (Figure 7).

Figure 5. Map of ‘The Worldwide Distribution of Germandom’, in All-Deutscher Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1900).

Figure 6. Percentage of world’s land in All-Deutscher Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1900).

Figure 7. Percentage of world’s population in All-Deutscher Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1900).

While these smaller maps seem to provide, on a first view, ‘neutral information’, reading them in conjunction with the main map serves as a justification for German imperialism towards the East. While the map on land distribution lists the Kaiserreich with 2.3 per cent of the world’s land and 4.2 per cent of the world’s population, the Russian Empire covers 16.5 per cent of the world’s land but has ‘only’ 8.7 per cent of the world’s population.Footnote 98 These numbers create an imaginary where Germany is too small for its growing population while Russia has more than enough land. Put differently, there is enough ‘empty’ space for German colonialism in the East. Another map of the atlas, which is coined ‘Germany towards the East’ (‘Deutschland nach Osten’) (Figure 8), depicts the spread of Germandom in the East of Europe. Two auxiliary maps portray ‘Germandom in the Baltic Countries and the Black Sea’ (Figure 9), depicting ‘German settlements’ in pink and leaving everything else blank.

Figure 8. Map on ‘Germany Towards the East’, in All-Deutscher Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1900).

Figure 9. ‘Germandom in the Baltic Countries and the Black Sea’, in All-Deutscher Atlas, Justus Perthes Gotha (1900).

The last two sections discussed two episodes of the use of blank spaces on maps in the context of the German colonial and imperial discourse. Juxtaposing these two episodes demonstrates similarities and difference. While the blank spaces in Stielers Hand-Atlas and Petermann’s expeditions could serve as moments of imagination of a future German colonial enterprise towards Africa, Langhans’s blank spaces could do the same for spaces in Central and Eastern Europe: creating colonisable land. The first one operates with the assumption that an ‘empty’ space has to be made knowable to ‘the European’. The second project assumes that a ‘filled’ space needs to be emptied and made unknowable to ‘the European’. Moreover, both projects also had repercussions for the politics of constructing ‘Germany’ itself. For a figure like Petermann, scientific explorations were closely tied to creating a political entity that was realised through the Kaisserreich of 1871, while in Langhans’s Pan-German project ‘Germany’ did not equal the official state but was constructed through a population-based notion of Germandom.

Conclusion

The social sciences and humanities in general and IR specifically are organised around what Julian Go has called ‘analytic bifurcation’, which artificially structure and divide analytic spaces into, for example, Europe/non-Europe, inside/outside, and state/empire. Historical work focusing on connections and entanglements has been important when it comes to problematising and theorising these separations. Therefore, the starting point of this article was a reconstruction of how scholarship focusing on connections and entanglement has addressed the metropole/colony bifurcation. Building on this, we suggest that two aspects have not (yet) received sufficient attention: first, connections between colonial spaces rather than between metropole and colony and, second, the Europe/non-Europe division. By problematising this, we have pointed to processes of hierarchisation within Europe and how, in particular, the European East has been constructed as a space of ‘othering’. Thus, instead of approaching and contrasting ‘Europe’ and ‘non-Europe’ as closed containers, our contribution points to the need to analyse imperial and colonial spaces in Europe and outside of Europe as connected. This makes previously invisible connections between different colonial spaces visible. We reconstructed how mapping practices, specifically the use of blank spaces, were applied during the nineteenth century to construct imaginaries of colonisable land in spaces outside of ‘Europe’, in particular Africa, and in the project of the ‘colonies of the East’.

These two examples of the use of blank spaces, one in Africa and one in the East of Europe, demonstrate how the hierarchisation of knowledge made ‘local’ knowledge and population invisible within maps. In the first example of maps of Africa, blank spaces were used to create an imaginary of ‘scientific progress’ and to differentiate between what is ‘known’ and what is ‘unknown’ to ‘the European’. Yet, as we have shown, knowledge was far more precarious. For instance, ‘indigenous’ knowledge was excluded from maps, while, at the same time, European speculation about imaginary mountains could be included. Thus, the use of blank spaces in these maps exemplifies how ‘cartographic science became, within the European discourse, a crucial marker of difference between Europeans (the knowing Self) and non-Europeans (the un-knowing Other).’Footnote 99 Such a dynamic of the hierarchisation of knowledge continues in our second example of Paul Langhans’s ‘translation’ of a völkisch-nationalistic programme of the Pan-German League into the Deutscher Kolonial-Atlas and other cartographic products. In these maps, ‘cartographic violence’ of imperial and colonial mapping becomes visible as large populations of the East of Europe are actively written ‘off the map’.Footnote 100 The two examples illustrate how the hierarchisation of knowledge was visualised in maps to make ‘other’ forms of knowledge and ‘foreign’ population invisible.

Our contribution also draws attention to broader implications and future avenues for critically engaging with (the history of) the making of the international. There are two points that might be interesting. First, focusing on one analytic bifurcation alone runs the danger of overlooking important connections, entanglements, events, and hierarchies. This means one needs to broaden the perspective by analysing different bifurcations and their interplay. In the present article, we have explored how multiple hierarchies link spaces and processes, which have been traditionally taken as being separated and isolated. We have done this by problematising ‘Europe’ and the multiple hierarchies within this space – a space that is usually conceptualised as a homogenously bound entity. Elaborating, for example, on Germany’s place between ‘heroic Europe’ and ‘epigonal Europe’ makes a variety of concurrent hierarchies visible. It thereby draws attention to how Germany moves between these different ‘Europes’ by invoking colonial imaginaries and how this can be read as an attempt to situate itself within the hierarchies of the international. Second, problematising different analytic bifurcations draws attention to dynamics in ‘spaces’ beyond predefined ‘metropoles’ and predefined ‘colonies’. This enables to study relations between differently constructed spaces such as East/West, Europe/non-Europe, or inside/outside. It thereby highlights how these imaginaries produced space through the employment of technologies of power but also how these technologies produced these spatial imaginaries in the first place.

Acknowledgements

This article has been in the making for quite some time. For support, discussions, and comments at different stages, we would like to thank Oliver Kessler, Pinar Bilgin, Luis Lobo-Guerrero, Julia Costa Lopez, and Benjamin Herborth. Earlier drafts have been presented at the 2021 EWIS workshop ‘Making the State-System Unfamiliar: The Dynamics of the Global Empire-System, 1856–1955’ and at the research colloquium of the Center for Political Practices and Orders, University of Erfurt, in 2022. We would like to thank all participants for their feedback. We would also like to thank Sven Ballenthin and the Gotha Perthes Collection for help with the archival material and providing us with digital reproduction of the maps. Finally, we would like to thank the journal editors and three anonymous reviewers for their guidance, constructive comments, and suggestions.