Introduction

‘In our time we have come to live with moments of great crisis’ - US President Lyndon Johnson’s observation rings as true today as when he made it almost six decades ago. While the disruptive events and processes we call crises can be very real and destructive in their impacts – as the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated – crises are also discursively constructed in political fora, such as the speech on voting rights Johnson delivered to Congress in 1965. Politicians use crisis rhetoric strategically to heighten attention to issues, emphasise the urgency and scale of challenges, and show their sincerity and commitment to addressing problems through policy action. Crisis rhetoric is typically woven into crisis narratives designed to tell compelling stories about how a policy problem arose, who caused it, who it affects, and who and/or what will solve it (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ‘t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2016). These narratives often stress that some parts of society suffer disproportionately from the crisis, and that the ‘victims’ deserve additional support and/or rights from the community (Boin et al., Reference Boin, McConnell, ‘t Hart, Boin, McConnell and ’t Hart2021).

Scholars of policy change have convincingly shown that crisis narratives can be used to justify radical reform, galvanising politicians and bypassing the normally circuitous, incremental, and clientelistic processes of agenda setting and policy change (Hall, Reference Hall1993; Herweg et al., Reference Herweg, Huß and Zohlnhöfer2015; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2003). This suggests crises can be opportunities for progressive redistribution (McDowell, Reference McDowell2023). Yet, existing research on redistribution during crises paints an ambiguous picture, with some finding that responses depend on the ideology of the parties in power (Hornung & Bandelow, Reference Hornung and Bandelow2022), while others note a general tendency to shrink welfare states and increase inequality during crises, irrespective of the ideology of governing parties (Kuipers, Reference Kuipers2006). Scholars have observed that underlying attitudes toward progressive redistribution in the welfare state did not shift significantly during the pandemic (de Vries et al., Reference de Vries, Geiger, Scullion, Summers, Edmiston, Ingold, Robertshaw and Young2023). Others have argued pandemic era crisis narratives reinforced neoliberal discourses of personal responsibility and fiscal austerity (Biswas Mellamphy et al., Reference Biswas Mellamphy, Girard and Campbell2023). Crisis frames used during the pandemic may therefore have had little positive impact on support for greater redistribution and may even have had a regressive impact. Bottero (Reference Bottero2020: 133–134) notes that political and public pressure and support for redistribution depends on the presence of narratives that cast inequalities as injustices rather than inevitabilities. As a result, the implications of crises for redistribution, along with how different political parties deploy crisis narratives to drive or oppose redistributive policy change, are unclear.

This paper examines crisis narratives deployed during COVID-19. We focus on housing policy because in many parts of the world, the pandemic and its aftermath exacerbated existing housing pressures, which were experienced disproportionately by already disadvantaged groups (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Daniel, Beer, Rowley, Stone, Bentley, Caines and Sansom2022; Wetzstein, Reference Wetzstein2017). Political actors in several jurisdictions have framed these developments as a ‘housing crisis’, and there has been increased political pressure for policy action to address enduring problems of housing affordability and security (Hochstenbach, Reference Hochstenbach2024; Parsell & Pawson, Reference Parsell and Pawson2023). Work on previous episodes of housing stress, such as the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, shows how a crisis can lead to short term redistributive social policies without structural change (Marchal et al., Reference Marchal, Marx and Van Mechelen2014). Housing crisis narratives can also be mobilised to support regressive redistribution via bailouts for investors, welfare retrenchment and pro-market deregulation, obscuring or worsening structural problems which pre-date the crisis (Hochstenbach, Reference Hochstenbach2024; Roitman, Reference Roitman2013). Our paper seeks to determine empirically the extent to which pandemic era housing crisis narratives rhetorically supported redistribution, along with the direction (progressive, regressive, or horizontal) of any proposed redistribution.

We apply the Narrative Policy Framework to analyse all speeches in the Australian Parliament from March 2020–2023 where ‘housing crisis’ was mentioned. We apply a novel deductive theoretical framework that distinguishes between three redistributive crisis narratives – retrenchment, Robin Hood, and restoration – to determine which narrative was dominant, and to understand the extent to which and how political parties across the ideological spectrum mobilised each narrative. Furthermore, the crisis literature suggests that support for policy change in a crisis is often dependent on the incumbency status of a political actor, that is, whether they are in government, opposition, or holding the legislative balance of power (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009: 93–96). We therefore also inductively explore the influence of incumbency and changes in incumbency status on political actors’ support for redistribution within their crisis narratives.

The results show that progressive redistribution (Robin Hood) narratives were more prominent than regressive narratives in Australian housing debates at the national level during and after COVID-19, but that mixed, or hybrid, narratives were dominant. We also find that changes in incumbency status and the relative power of different parliamentary parties led to strategic changes in narratives, with political actors embracing steadfast, focusing, or hybridisation strategies, with implications for their redistributive ambitions. Our research provides a novel theoretical framework for conceptualising redistributive crisis narratives, along with original empirical data to demonstrate the role of partisanship and incumbency in shaping the possibilities for redistribution in a crisis.

The next section of the paper addresses the existing literature on crisis narratives and presents a typology of redistributive crisis stories, along with theoretical expectations of how party ideology and incumbency should influence take-up of the different narratives. We then outline the research design and methods, followed by a discussion of our empirical findings. The discussion documents the narrative strategies political actors use to deal with changes in their incumbency status during a crisis and reflects on the implications for knowledge about the relationship between crisis narratives and redistribution.

Crisis narratives and redistribution

While the situations we call crises often have very real impacts, the implications of crises for public policy and society are mediated by the way in which crises are framed, and how the story of a crisis is told by political actors (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ’t Hart and McConnell2009; Goffman, Reference Goffman1974). The narrative approach to studying public policy highlights the critical importance of stories for political actors’ mobilisation of support for their agendas, strategic framing of policy problem definitions, and promotion of preferred policy solutions (Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Jones and McBeth2018a). In this section we explain how we use a leading approach to studying storytelling in policy, the Narrative Policy Framework (NPF), to examine the links within policy narratives between crisis frames and redistributive policy proposals. We also note that existing NPF literature under-theorises the impact of political and partisan dynamics on narratives. This is important because while parties of left and right have distinct ideological orientations and therefore will be inclined to put forward different crisis frames, their crisis narratives may also be influenced by their incumbency status (government versus opposition), and the extent to which they depend on the support of other parties with different ideological positions within the parliament (Iversen & Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2006; Mulé, Reference Mulé2001; Starke et al., Reference Starke, Kaasch and Hooren2014).

The NPF offers a set of concepts to organise the analysis of stories systematically, including settings, plots, characters, and morals (Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Jones and McBeth2018a). Settings refer to the background conditions referenced in narratives, while the plot is the causal logic that ties together the sequence of events in the narrative. A key element of setting and plot is the temporal and spatial scope of problems and solutions in their narrative plots (Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Raile, French and McEvoy2018b). Characters include villains, who visit suffering on a group of victims by creating or sustaining a policy problem. Heroes oppose and overcome the villains to save the victims. The moral of the story encapsulates the desired path forward – what does this story tell us about what needs to happen to ensure the victims are saved from the villains by the heroes, and what have we learnt in the case of policy failure?

Using the NPF we can systematically identify comparable structures and narrative elements used in the process of policy development and discursively connect actors to policy initiatives and their political timeframes. While there are many different potential morals that emerge from policy narratives, we are interested in the subset of policy solutions that involve redistribution. We draw on Kuhlmann and Blum’s Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021 work on COVID policy narratives, which in turn develops Lowi’s (Reference Lowi1972) distinction between ‘redistributive’, ‘regulatory’, and ‘distributive’ policy instruments. Redistributive instruments explicitly take resources from one part of society and transfer them to another subgroup. By contrast, regulatory instruments do not involve the transfer of ‘treasure’ but instead use authority to control citizens’ behaviour and/or the operation of markets. However, they may also have redistributive implications, especially where regulations are used to protect the vulnerable and/or give rights to the disadvantaged. Distributive instruments are framed as those solutions that provide benefits that are universally enjoyable, while the resources to fund them are not extracted from a particular group. Distributive instruments have the political advantage of spreading benefits widely while not singling out a specific group to pay new taxes or comply with new regulations, that might therefore feel aggrieved by the impost.

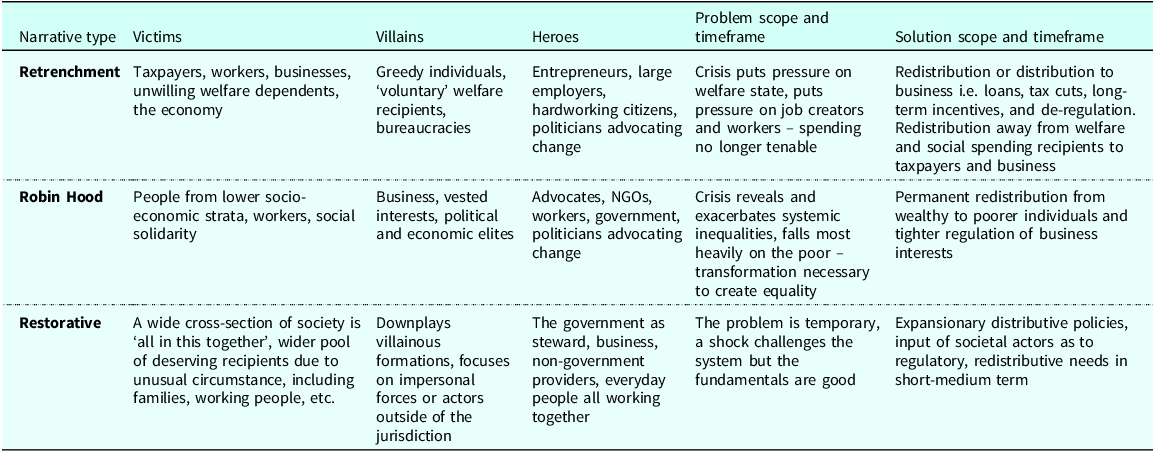

In this paper we apply these narrative concepts to crises. Crisis narratives typically create a sense of an urgent and consequential threat, which needs to be addressed to avoid serious harm, using emotionally charged language, along with unambiguous villains, victims, heroes, and morals/solutions (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ‘t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2016: 26–27). Yet, existing research paints a contradictory picture of the implications of crisis narratives for redistribution. Given the insights of NPF studies, it should be expected that crisis narratives will likely take a limited number of forms in each policy area, with potential variation to be observed across ideological and partisan dimensions. For example, countries where right-wing parties govern more often are found to have less progressive redistributive regimes (Iversen & Sosckice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2006). We follow Bierre et al. (Reference Bierre, Keal and Howden-Chapman2023) in analytically structuring the narratives into their problem formulations, and the solutions/morals presented as a corollary of them. We do so because this helps us understand the full causal logic of the narratives in terms of the scope of the problem and the change required to address it. In each narrative we also highlight the key characters, scope, aims, and likely redistributive outcomes of the policy solutions proposed. Taken together, the characters and plots involved in both the problem and solution formulations of a policy narrative lead to the moral, which the audience may infer. Table 1 synthesises narratives from the existing crisis literature and identifies three main redistributive themes. We next explain these in more detail before applying them to the housing case study.

Table 1. Three redistributive crisis narratives and their components

The first narrative we expect to see emerge from a crisis is a story of ‘retrenchment’. In this story, the crisis is constructed as a problem caused by larger economic forces beyond the control of the government, that nevertheless requires dramatic policy adaptation. On the problem definition side, spending on welfare or social programs has become untenable given the economic pressures now facing the state, and this spending may even have contributed to the crisis. The victims of this scenario are taxpayers, workers facing job losses and even the recipients of social support who have become dependent and unable to support themselves properly. Villains include inflated and inefficient state bureaucracies, along with people who depend on welfare ‘by choice’. Ideas like fairness or criminality may be deployed to stoke resentment of welfare recipients to bring the public on board with policies which worsen inequality (Hoggett et al., Reference Hoggett, Wilkinson and Beedell2010). Alternatively, if the problem is unequivocally a market failure, such as in the GFC and sub-prime mortgage crisis, lawmakers may blame greedy individuals or lax regulators within an otherwise well-operating system (Roitman, Reference Roitman2013). This problem formulation negatively politicises government redistribution to the less wealthy, while limiting the range of solutions to those which favour market-based approaches.

Retrenchment narratives combine two strands of solution. One strand, dominant in the policy discourse of powerful actors like the IMF (Kentikelenis & Stubbs, Reference Kentikelenis and Stubbs2023) involves reducing the perceived largesse of the state, requiring austerity to cut spending on wasteful welfare for the long-term benefit of hardworking taxpayers. In Kuhlmann and Blum’s (Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021) terms, this is a distributive story of ‘withdrawing to take people out of helplessness’. The other strand then holds up heroes like entrepreneurs and large companies as worthy agents of restorative social change, who will help the economy to build back stronger. For this solution to resolve the crisis, the public must be incentivised to work, while businesses will require temporary assistance ‘bailouts’, and a longer-term business environment conducive to their flourishing. This involves presenting regressive redistribution and spending on private businesses as distributive, a story of ‘providing to promote’ which will benefit all (Kuhlmann & Blum, Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021). On the regulatory side, ‘red tape’ should be slashed to ‘liberate’ the market and promote general wellbeing (Kuhlmann & Blum, Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021). In this way, actions which involve the redistribution of wealth upwards are depoliticised in the context of crises as part of what scholars have identified as the hidden welfare state of ‘privatised Keynesianism’ (Crouch, Reference Crouch2009), and ‘socialism for the rich’ (Stiglitz, Reference Stiglitz2009).

In Australia, government support and subsidies which encourage private home ownership (Berry, Reference Berry1999; Kholodilin et al., Reference Kholodilin, Kohl, Korzhenevych and Pfeiffer2023) and privilege the regulatory perspectives of housing developers (Gurran & Phibbs, Reference Gurran and Phibbs2015) have long guided housing policy. To buttress this position, prevailing policy narratives have constructed homeowners as hardworking people worthy of assistance (Fox O’Mahony & Overton, Reference Fox O’mahony and Overton2015), while users of government-provided housing are portrayed as undeserving (Kuskoff et al., Reference Kuskoff, Buchanan, Ablaza, Parsell and Perales2023), and struggling renters in the private sector are victims of circumstance (Hulse et al., Reference Hulse, Morris and Pawson2019). In the context of housing crisis discourse, scholarship points to the dominance of ‘neoliberal’ ideological framing and pro-market narratives in housing (Biswas Mellamphy et al., Reference Biswas Mellamphy, Girard and Campbell2023). In New Zealand, contestation over poor standards in rental and social housing was co-opted by the governing centre-right National party in ways which portrayed investment property owners as heroes (Bierre & Howden Chapman, Reference Bierre and Howden-Chapman2020) and presented the solution to the housing affordability crisis as requiring liberalised regulations to allow market actors to increase the supply of housing (White & Nandedkar, Reference White and Nandedkar2021). The existing housing crisis literature therefore creates the expectation that a ‘retrenchment’ narrative will most likely be deployed in a crisis in the contemporary era, especially by parties with right or centre-right ideological positions.

The second crisis narrative is a ‘Robin Hood’ story of progressive or equalising redistribution. In this story, a crisis is constructed as falling most heavily on those in society least able to bear it, with knock-on effects which may harm the broader economy or destabilise society. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, precariously employed frontline workers had no choice but to continue to work, subsequently contributing to the spread and morbidity of the virus (Côté et al., Reference Côté, Durant, MacEachen, Majowicz, Meyer, Huynh, Laberge and Dubé2021). However, rather than simply blaming the workers as individuals, this narrative highlights systemic features of the political and economic regime and paints the consequences of entrenched inequality negatively (cf. Piketty, Reference Piketty2014). This kind of narrative has a long pedigree, appearing in the rhetorical appeals of progressive politicians like Franklin Roosevelt in the United States or the left-of-centre UK Labour party after World War Two (Jackson, Reference Jackson, Callaghan and Parker2009: 236-240). In more recent times, political parties of the far left commonly justify their redistributive agendas with anti-elite Manichean populist rhetoric which resonates with a Robin Hood narrative (Rooduijn & Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017). In widespread economic crises the political incentives to use such a narrative are heightened because more people are perceived as victims of circumstances beyond their control and therefore worthy of assistance (Uunk & van Oorschot, Reference Uunk and van Oorschot2019). However, a Robin Hood narrative also identitifies villains responsible for the crisis, such as greedy corporations and other vested interests (in housing, investment property-owning elites). This morally charged argumentation adds to the salience already present in crisis framing to help justify more coercive regulatory models and greater downward redistribution, which combines Kuhlmann and Blum’s (Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021) ‘taking to take’, ‘restricting to control’ the unworthy, and ‘giving to give’ to the deserving.

There has been convergence in economic policy between parties of the ideological centre-right and centre-left in recent decades. At times center-left parties have been the standard bearers able to push forward retrenchment narratives (Kuipers, Reference Kuipers2006: 24) while under electoral pressure parties of the centre-right may push for renewed public investment in housing (Hochstenbach, Reference Hochstenbach2024). Despite this, we would expect that parties of the centre-left or left would be more likely to deploy a Robin Hood narrative than others, particularly when this is electorally beneficial to differentiate themselves from their opponents. For example, in German debates over wealth redistribution, the Social Democrats consistently draw on discourses of social justice for the poorer members of society and families to justify taxes on the wealthy, in contrast to the retrenchment arguments of the Christian-Democrats (Hilmar & Sachweh, Reference Hilmar and Sachweh2022). In the context of a housing crisis, White and Nandedkar (Reference White and Nandedkar2021) and Bierre and Howden Chapman (Reference Bierre and Howden-Chapman2020) highlight the crisis counter-narratives put forward by opposition parties of the political left in New Zealand, which pushed for redistributive and regulatory policy in housing. The opposition NZ Labour, Green, and Māori parties argued, on behalf of heroes such as social welfare NGOs and advocates, that longer term market and tax interventions were necessary to redress safety and affordability concerns. These arguments presaged the kinds of policies, such as increased spending on social housing and winding back of tax incentives for investment properties, pursued with mixed results by Labour when they came into government (Smyth, Reference Smyth2021).

Our third narrative sees crises become opportunities for politicians to exercise their rhetorical leadership to claim that the polity are ‘all in this together’ in the face of an unprecedented shock caused either by outside forces, or domestic factors which could not be controlled. Rather than ‘divisive’ redistribution of resources and/or restructuring of the system, this narrative suggests a crisis is something that is best addressed through temporary expansionary distributive policies. In the wake of the GFC for example, leaders in Australia, the UK, and Ireland were quick to blame outside banking sectors for the crisis, and in Australia suggested rapid and widespread stimulus spending was necessary to ‘save the economy’ (Masters & ‘t Hart, Reference Masters and ‘T Hart2012). A similar narrative emerged in Australia during COVID-19, when the largest spending program in Australian history was deployed to subsidise furloughed workers (Klein et al., Reference Klein, Cook, Maury and Bowey2022). By using this kind of ‘restorative’ narrative, politicians reinforce the temporarily bounded ‘setting’ of the problem (Shanahan et al., Reference Shanahan, Raile, French and McEvoy2018b) and problem solutions of ‘giving to promote’ the general wellbeing of all (Kuhlmann & Blum, Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021), or of broad victim groups like ‘families’ or ‘everyday’ people. Where this stimulus can be directed at the less wealthy, it is framed not as redressing a systemic imbalance, but highlights the increased size of the pool of deserving recipients under exceptional circumstances. In some crises, a restorative narrative might also involve short term regulatory action such as the need to restrict people’s activities during the pandemic (Kuhlmann & Blum, Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021). Unlike in a retrenchment narrative, which valorises the role of business and market forces, the restorative narrative constructs heroes out of a broad coalition of government, non-government organisations, everyday citizens and business groups.

Due to the fact this restorative narrative is designed to elicit a broad base of support, while shifting blame away from the existing government, we might expect parties of the left or right to be equally likely to embrace it especially when they are incumbent (Boin et al., Reference Boin, ‘t Hart, Stern and Sundelius2016). However, given their propensity for supporting market-based solutions and fiscal restraint, parties of the right may more naturally tend toward retrenchment (Iversen & Sosckice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2006). Similarly, challenger parties of the far left or right in opposition could be expected to bolster their claim to take government in more morally charged terms tending toward a Robin Hood or retrenchment approach (Rooduijn & Akkerman, Reference Rooduijn and Akkerman2017; de Vries & Hobolt, Reference de Vries and Hobolt2020). We therefore expect that incumbent parties of the centre-left would have the greatest incentive to rhetorically demonstrates their fitness to govern ‘for everyone’, in contrast to more ideologically extreme competitors on the left and right.

In addition to the limited research on the redistributive content of crisis narratives, the way crisis narratives may change or be abandoned, or exert a rhetorical ‘path dependency’ (Grube, Reference Grube, Uhr and Walter2014) as a party moves from opposition to incumbency is understudied. Similarly, given the complexities of maintaining political support and the influence of pre-existing institutions on the policy-making process, the take-up of these narratives or the way they may be mixed together cannot be assumed. Therefore, in our findings section, we seek to test our expectations of which kinds of narratives will likely dominate in a housing crisis, and which parties, in terms of ideology and incumbency status, will put forward each type. We also wish to understand the dynamics and rhetorical strategies which evolve in partisan debate in a crisis over time. Our case selection strategy and methodology are explained next.

Australia’s housing crisis debate

To study the role of redistribution in crisis narratives, we focused on debates about the housing crisis in Australia’s federal parliament between 2020 and 2023. Housing policy represents a set of shared problems across high income countries, with narratives of housing crisis linked to concerns about affordability, insecurity, and inequality common in these jurisdictions (Wetzstein, Reference Wetzstein2017). Within the housing field, Australia exemplifies the paradigm shift from a ‘homeowner society’ to a neoliberal investor model (Redden, Reference Redden2019). Policy changes such as the removal of inheritance taxation and the introduction of income tax deductibility for private housing investment in the 1980s have had a negative impact on home ownership rates. This also created a large constituency that opposes expanded rental rights and seeks to maintain high house price values. Persistent declines in public investment in public and social housing, combined with increases in permanent and temporary immigration, have put significant pressure on the rental market. At the same time, historically high levels of home ownership in Australia and an entrenched belief that Australia is a meritocratic ‘land of the fair go’, created a cultural bias against renting, with an assumption that only poor people rent, and a weak regime of renters’ rights (Kholodilin et al., Reference Kholodilin, Kohl, Korzhenevych and Pfeiffer2023).

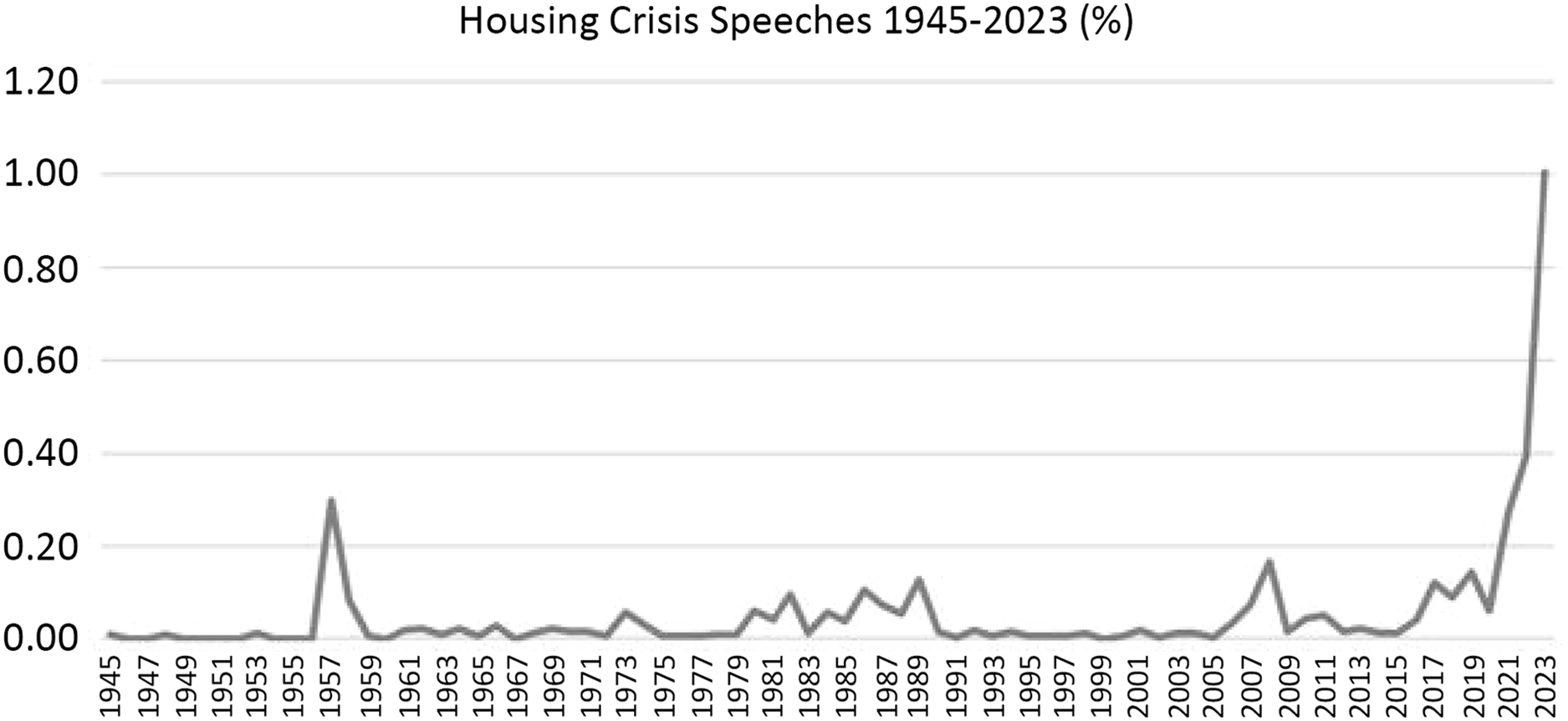

The period 2020–23 was chosen as a useful test of the role of redistribution in housing crisis narratives. While housing is a perennial topic of debate in the Australian Parliament, and ‘crisis’ rhetoric has been frequently invoked since 1945, the period 2020–23 represents a dramatic intensification of ‘housing crisis’ discourse, easily outstripping earlier periods of upheaval, such as the late 1980s property market crash and GFC, as shown in Figure 1. Despite Australia escaping widespread loss of life due to COVID-19, policy and economic changes during the pandemic created acute problems of housing affordability, especially for renters (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Daniel, Beer, Rowley, Stone, Bentley, Caines and Sansom2022). Furthermore, the immediate political context of the pandemic created a particularly hostile environment for structural redistribution in the context of housing. In 2019 the centre-left Australian Labor Party (ALP) opposition went to the election with an ambitious redistributive agenda. Among the proposals was a promise to remove tax deductibility of investment property income (negative gearing). The conservative government ran an effective scare campaign about the ALP policy’s effects on housing supply, and when the ALP lost the election, it explicitly ditched the policy, along with its other redistributive initiatives (Harris, Reference Harris2021). Thus, when the pandemic arrived, Australia was governed by a pro investment, anti-redistributive conservative party, and led by a PM who responded to concerns about rental affordability by suggesting renters should buy houses (Wahlquist, Reference Wahlquist2022). We should expect such conditions to reinforce pressures for retrenchment and to a lesser extent restoration, but to offer little room for Robin Hood narratives.

Figure 1. Housing and crisis speeches 1945-2023.

At the same time, Australia’s pandemic period presents an important element of variation on our independent variables. Despite broad public approval of the way the conservatives handled the pandemic, the government lost the March 2022 election and was replaced by Labor. Furthermore, the balance of power holders in Australia’s upper house of Parliament (The Senate) shifted from right-wing minor parties to a left-wing minor party with strong commitments to housing affordability and redistributive policy agendas. We can thus observe a shift in incumbency among key political parties during the period under study and determine the extent to which these shifts were associated with a change in the redistributive content of crisis narratives for the political actors involved.

In terms of our empirical sample, we created a corpus of all speeches in the Australian Parliament from March 2020 to March 2023 in which the phrase ‘housing crisis’ was mentioned. This phrase, which has been studied before in housing literature (Hochstenbach, Reference Hochstenbach2024), was chosen, rather than a more diffuse discussion of housing discourse in the period, because it allowed in-depth qualitative coding of the narrative elements of crisis speeches. Our sample of 239 housing crisis speeches exceeds other analyses of parliamentary records in the social policy field (Curchin et al., Reference Curchin, Weight and Ritter2024: 39) and is similar to other NPF studies (Kuhlmann & Blum, Reference Kuhlmann and Blum2021). Our data analysis methodology proceeded in three stages. First, we identified the party affiliation and incumbency status of the speakers. Second, to determine the extent to which our narrative frameworks were utilised we assessed in each speech (1) how the problem was defined in terms of its scope and the key victims and villains involved, (2) how the solution to the problem was defined in terms of the scope of change required, (3) whether regulatory, redistributive, and/or distributive policy instruments were suggested as well as their target populations, and (4) the identity of the heroes who would enact these changes. Finally for each speech we could then put these elements together to identify the takeaway ‘moral’ of the story and how closely it conformed to the structures of the retrenchment, Robin Hood, and restoration narratives. Where a narrative combined elements of multiple narrative types, we coded these in terms of their mix.

Additionally, we were open to the possibility that housing crisis speeches would fit some other narrative form outside of our typology (such as narratives that are neither redistributive nor restorative), as well as unstructured ‘drive by’ mentions of the housing crisis phrase that lack a narrative form. This is important because it allows us to determine the empirical limits of our typology. We also took note of how each party’s narratives evolved over time, and as their relative power or incumbency changed in parliament. To address our questions, we next discuss our findings in terms of the overall dominant narratives in our case, then explore how they were taken up by the various parties in parliament, and how this changed over time and with shifts in incumbency.

Dominant narratives

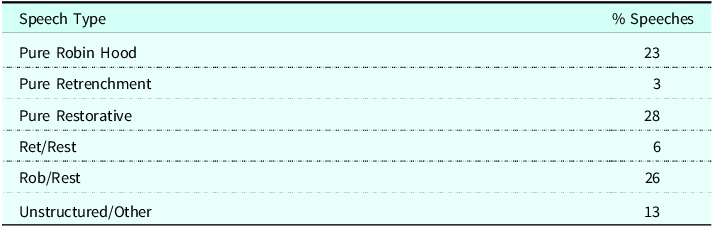

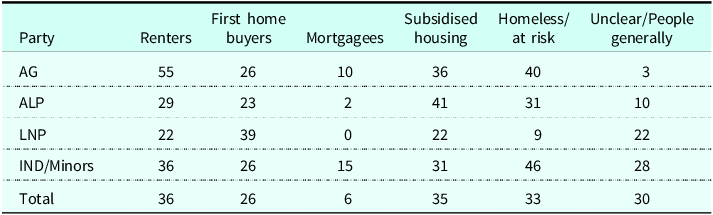

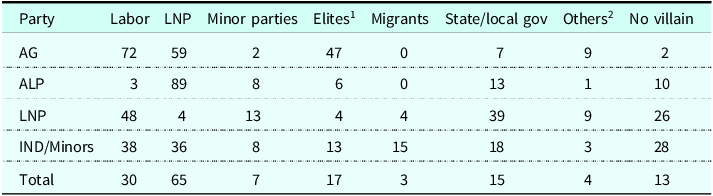

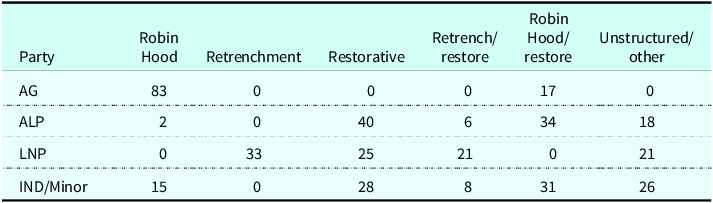

Parliamentary housing crisis discourse in the period 2020–2023 centred primarily around restorative and Robin Hood narratives. As well as appearing in pure form, we also saw these narratives combined in competing visions of redistributive and distributive solutions to problems of affordability, supply, and access to housing across tenure types (see Table 2). We found evidence for our three crisis narratives in 87 per cent of speeches that mentioned ‘housing crisis’. Our crisis narrative types are made up of a cast of actors (heroes, villains, and victims), which help to give a human dimension to problem definitions and their solutions. The dominance of Robin Hood and restorative narratives is reflected in the broad cast of crisis-impacted victims invoked by parliamentarians (Table 3). As well as concerns around the impact on society generally, parliamentarians highlighted the struggles of ‘everyday’ people made homeless and/or those in need of social housing, affordable rental accommodation, and a chance to buy their first home. Of least concern to parliamentarians were existing mortgage holders. As shown in Table 4, the villains responsible for the housing crisis were not, as in a retrenchment narrative, the users of social services or bureaucracies in need of reduction. Instead, other political parties, either at the federal or state levels of government, were the primary villains for many speakers, either because they had allegedly neglected problems in housing or were opposed to their solutions.

Table 2. Percentage of narrative types (% speeches)

Table 3. Victim definitions (% speeches)

Table 4. Villains by party (% speeches)

1 Property developers, banks, wealthy property owners

2 Bureaucrats, internal migrants, people working from home, foreign powers, DV perpetrators

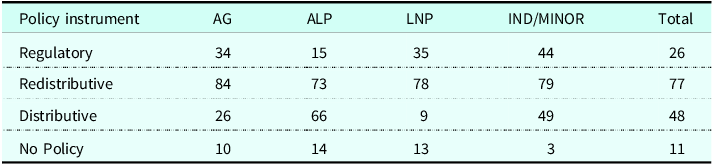

In keeping with the strong presence of Robin Hood narratives, economic elites, especially bankers and property developers, were positioned as complicit in the crisis and were the most common societal actors to blame. However, Table 5 shows that regulatory policy instruments designed to coerce prosocial behaviour in the housing market were less frequently invoked than redistributive and distributive policy instruments. Beyond these numbers, the relative strength of the restorative narrative is revealed when we examine the differing perspectives on housing crisis put forward by the main political parties.

Table 5. Suggested policy instruments (% speeches)

Partisan crisis narratives

In our sample, we can find three major crisis narratives. The most frequently invoked crisis constructions were the restorative narratives of the ALP (see Table 6). These narratives highlighted the negative impacts of COVID-19 and neglect by the Liberal/National conservatives of ‘everyday’ workers, prospective first home buyers, and women fleeing domestic violence. For the most part this was not a systemic critique of market provision of housing. Instead, crisis conditions were put forward by Labor speakers as evidence of a system requiring more stewardship and long-term investment by the federal government and cooperation between state and local authorities, non-government providers, and the private sector to address lack of housing supply. Where their narrative combined Robin Hood and restorative elements was in an emphasis on the need for targeted support for people in lower socio-economic strata, women, children, Indigenous Australians, and essential workers. Rather than regulation of private rental markets, ALP speakers tied the housing crisis to a concurrent problem of insecure work and low wages to be addressed through training and industrial relations reform.

Table 6. Narrative types (% speeches)

The second most frequent crisis narrative involved a clearly prosecuted Robin Hood story put forward by the Australian Greens and some independents. These speeches highlighted the plight of victim groups like marginalised minorities as well as young and lower socioeconomic people locked out of affordable, secure housing to rent or buy. They also used ‘housing crisis’ to critique structural problems in a system described as ‘broken’. In this narrative, insufficient provision of publicly owned housing, along with tax and regulatory structures that favoured economic elites and investment property owners, needed to be addressed through government action. In this way, the wealthy could be made to pay their fair share, housing could be partially decommodified, and the government would have funds left over to build hundreds of thousands of new homes to address the acute demand for public housing.

By contrast, the clearest retrenchment narratives were deployed by the conservative Liberal/National coalition. From their perspective, a crisis of undersupply of housing was best addressed by redistribution designed to encourage home ownership through grants for first homeowners or to encourage new construction. They were opposed to the distributive ideas of the ALP, with some Liberal/National politicians believing the construction of social housing would encourage government dependency (or they shifted responsibility by asserting this was more appropriately a problem for state governments to address). Similarly, Liberal/National members saw state and local government planning regulation as harming the ability of the private sector to provide sufficient housing and called for de-regulation. We conclude that political actors’ crisis narratives were broadly coherent with their parties’ established ideological positions (White & Nandedkar, Reference White and Nandedkar2021). However, these narratives were not static. In the next section we show how changes in incumbency status and the parliamentary balance of power during our study period led to shifts in the redistributive content of crisis narratives.

Dynamics of narrative evolution

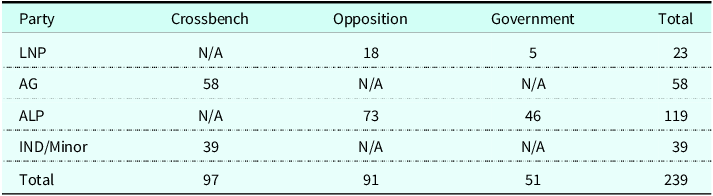

The centre-right Liberal Party of Australia and their coalition partners governed until an election loss in 2022. As shown in Table 7, while in power the LNP rarely mentioned the ‘housing crisis’ phrase, but took it up once in opposition, though still to a lesser extent than the Greens and other minor parties. The ALP made heavy use of the phrase to critique the government while in opposition, but also maintained their usage of it as they took office and began attempting to implement the programmes they took to the election. However, the outcome of the election meant they did not hold the balance of power in the Senate (Australian’s upper house, which can reject or amend legislation passed by the lower house). Instead, although the LNP had lost ground in the lower house they outnumbered the ALP in the upper house, meaning the Australian Greens were a necessary partner for passing contentious legislation. This scenario proved fertile ground for parties to compete for the moral high ground on housing issues and led to our identification of three distinct strategies of partisan narrative adjustment: hybrid, steadfast, and focused.

Table 7. Usage of housing crisis by governing status and party March 2020-March 2023 (N)

The ALP’s narratives took on a different complexion as they moved from opposition to government. In 2020–2021 they were more likely to combine their distributive policy arguments for the construction of new social and affordable housing with ‘drive by’ partisan attacks on the government containing no policy specifics. They also combined Robin Hood critiques of the government’s proposed policy of allowing workers to draw upon their superannuation retirement savings to buy houses, with retrenchment or restorative narratives. As they took government in 2022, their discourse became more likely to centre their two main restorative policy proposals: a Housing Supply and Affordability Council, which brings together community sector groups and business experts to create a better regulatory environment for housing construction, and the Housing Australia Future Fund (HAFF). This fund would borrow $10b to invest in the stock market in perpetuity and use the returns to fund social and affordable housing. This would create more housing for lower income earners with flow on effects to the rest of the housing system, which did not in theory add to government debt, require new taxes or create inflationary pressure. For the ALP, the narratives they deployed were for a ‘no losers’ correction to the market, overseen by a government which could coordinate collaboration between states, territories, business and the not-for-profit housing sector. However, the ALP faced opposition to their policies which led them to respond with a strategy of narrative hybridisation – mixing their restorative narrative with a Robin Hood strategy of targeted support for emergency housing for disadvantaged people.

The Liberal/National conservative coalition responded to its move from government to opposition by first acknowledging the crisis more fully, then defending their own legacy while criticising the ALP. Rather than changing the character of their narrative in response to their loss of power, the coalition story steadfastly remained one of a market needing correction, especially in rural areas, through deregulation and state governments stepping up on the marginal provision of emergency accommodation. For the Greens, both Labor and the conservatives were complicit in the production of a housing and taxation system, which favoured banks, property developers, and investment property owners at the expense of the less well off. Therefore, they also remained committed to Robin Hood stories with the change of government. However, over time, and given the opportunity of the balance of power, they focused their narrative. This involved narrowing their arguments from a general critique of the housing system, to attacks on the apparent inadequacies of the HAFF and neglect of renters as victims. They particularly focused their demands on federal action on the rights of tenants, proposing regulation of rents including a two-year freeze. This opposition precipitated a change to the ALP’s hybridisation strategy, which incorporated attacks on the LNP and Greens for blocking urgently needed housing. Labor combined their restorative policy proposal with redistributive Robin Hood elements, tying hundreds of millions of dollars of targeted support for veterans, women and children fleeing domestic violence, the homeless, and essential workers to passage of their legislation. Eventually in late 2023 the ALP agreed to amend the legislation to guarantee a minimum amount of spending each year and provide $2b of extra funding for state governments for housing. The Greens withdrew their opposition to the bill but continued to pressure the government on renters’ rights and price control.

Discussion and conclusions: redistributive implications of crisis narratives, partisanship, and incumbency

This research has shown that crisis narratives have an ambiguous relationship with redistribution. Redistributive policy involves governments taking from one group to give to another, a process that is fraught with political calculations and potential conflicts to manage. In the neoliberal era, when market-oriented policymaking is dominant and redistributive policies which worsen inequality have become ‘common sense’, these calculations frequently favour the already wealthy. These conditions also existed in Australia before the pandemic, with left-parties’ proposals to reduce housing inequalities defeated at the ballot box in 2019. However, when problems are framed as crises, the stakes of policymaking are raised, revealing weaknesses in the governing regime and giving political incentives to try new approaches or respond to perspectives which hitherto had been marginalised. Despite this, the experience of the COVID-19 crisis in many countries has been for stimulus policies which could address structural inequalities to be short-lived. Historically, responses to problems like the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the United States, or austerity policies in the UK and Europe, also led us to anticipate that redistribution in the face of a crisis would worsen rather than address inequality. Given this, we anticipated that retrenchment narratives would dominate parliamentary debate around the ‘housing crisis’ in Australia in 2020–2023.

Instead, we saw a more nuanced set of crisis narratives which combined elements of a ‘no losers’ restorative narrative with a desire to signal concern for the less well off. In part this was because of the Liberal-National Coalition’s reluctance to acknowledge a systemic crisis while in government. Instead, they shifted blame to COVID-era population movements and local and state governments and then remained steadfast in opposition. Nevertheless, across all ideological groupings, the widespread nature of the problem was acknowledged, and the struggles of ‘everyday’ people and disadvantaged groups were invoked to raise the saliency of issues of housing supply, access, and affordability. Once in government, the ALP’s attempts to introduce an active stewardship role for the federal government in improving the supply of affordable housing without committing to alterations of the tax code or a direct role in construction was contested by parliamentarians further to the left. Therefore, instead of incumbency leading a centre-left government to embrace a purely restorative narrative as we expected, the dynamics of partisan representation pushed them to commit to a hybridised crisis narrative incorporating redistributive policies toward ‘deserving’ groups. The left-wing Australian Greens deployed Robin Hood narratives, as one would expect. However, the partisan context and their acquisition of the balance of power moved their narratives away from arguments based on a systemic critique of market provision of housing. Instead, in the urgent context of crisis and the perceived need to secure tangible political and policy gains, they focused their narratives by rhetorically narrowing their concerns to push for regulatory market intervention on behalf of renters. In these ways, a widely acknowledged crisis in housing neither led to calls for the retrenchment of government support, nor radical redistribution of wealth which would displace or discourage market provision of housing. Rather, by focusing on the apparent neglect of the previous government and the need for a coordinated, long-term, and incremental approach to issues of supply, the housing crisis evoked in 2020–2023 laid the seeds for a housing system which is reformed, but not transformed.

What then can this case tell us about the partisan dynamics and redistributive policy implications of crisis narratives? We join those who have been sceptical about the capacity for crises to create progressive change and address structural inequalities. However, our findings also point to the continued potential of crisis narratives in parliaments to highlight emerging issues, widen the pool of ‘deserving’ targets for government assistance and give voice to alternative critical perspectives. Although there are acknowledged redistributive tendencies among parties of the centre-left (Iversen & Soskice, Reference Iversen and Soskice2006) and right (Hornung & Bandelow, Reference Hornung and Bandelow2022), whatever their ideological leanings, politicians are responsive to the dynamics of political debate, their relative strengths in parliament, and the organised mobilisation of social suffering. This is especially so given an electorate less strongly loyal to the dominant parties (Gauja & Grömping, Reference Gauja and Grömping2020) and the increased influence of challenger and populist parties on the redistributive policies of those in the ‘mainstream’ (Schumacher & van Kersbergen, Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016). In our case, a centre-left party reluctant to embrace radical change but open to an active role for government in addressing the needs of the less well-off was nudged, cajoled, and enticed toward a more redistributive policy that may have long-term transformative effects.

We suggest that the uses and abuses of crisis narratives by politicians are context-dependent and influenced by the power dynamics of parliaments. By focusing on both the range of actors identified as responsible for and affected by a crisis, as well as the use and direction of redistributive, distributive and regulatory policies, scholars can identify three crisis narratives used by politicians. By examining how they are used, mixed, and altered over time, greater clarity around the avenues for progressive and regressive social change in modern liberal democracies is possible. Similarly, for advocates and others inclined towards using a crisis frame, our findings demonstrate that it may be a double-edged sword for addressing inequality in housing, since it can entrench existing power structures as well as disrupt them.

Funding statement

Funding for this research was provided by the Australian Research Council Discovery Grant DP220101911.

Additional funding and support were generously provided by Griffith University’s School of Government and International Relations and the Centre for Governance and Public Policy.

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare.