A basic needs report of the California State University system estimated that 22·4 % of the student body is marginally food secure(Reference Crutchfield and Maguire1), defined as having ‘…problems at times, or anxiety about, accessing adequate food, but the quality, variety and quantity of their food intake were not substantially reduced’(2). Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, some studies have indicated that food security has decreased by as much as a third among college students(Reference Owens, Brito-Silva and Kirkland3,Reference Soldavini, Andrew and Berner4) . Recently, research has found positive associations between marginal food security and depression, BMI, less cooking and food agency, worse perceived health and lower grade point averages among college students(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5–Reference Payne-Sturges, Tjaden and Caldeira7). However, qualitative research has not been conducted among students experiencing marginal food security to explore these findings in the context of students’ lived experiences.

Food security status is a continuum, those with high food security have no concerns or anxiety about consistently accessing adequate food, those with marginal food security have some problems accessing adequate food, those with low food security report reduced quality and variety of diet with little indication of reduced food intake and those with very low food security report multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake(2). Low and very low food security are often combined to create a food insecure group and those with marginal food security are often combined with those with high food security to create a food secure group. However, past research in non-student populations has found that individuals experiencing marginal food security often have markedly different health outcomes than those who have high food security or those who are food insecure(Reference Cook, Black and Chilton8). For example, Cook et al. found that the adjusted OR for children experiencing fair or poor health for those who were fully food secure, marginally food secure and food insecure got progressively larger as their food security level worsened. The CI of these adjusted OR did not overlap which indicates these values were distinctly different(Reference Cook, Black and Chilton8). Sometimes there is not a clear relationship between food security status and a health outcome, such is the case where Leung et al. studied college students and found marginal and very low food security to be positively associated with BMI compared to those with high food security, while low food security was not(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5). Due to the potential differential effects of marginal food security on various health outcomes, a qualitative analysis is needed to provide context surrounding the recent findings that marginal food security negatively impacts students’ health and academic performance.

Prior qualitative work that investigated how food challenges impact student life has focused on students who experience food insecurity, or a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life(2). Student interviews suggest that food insecurity adversely affects students’ health, academics and other socio-cultural factors(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Bydalek, Williams and Fruh9–Reference Henry11) . Meza conducted twenty-five in-depth interviews with students recruited from a campus food pantry and with a general inductive approach identified several themes that highlight how students were negatively impacted by food challenges(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5). Students stated their food insecurity status added stress that interfered with daily life, led to a fear of disappointing family, resulted in resentment of students who are in better food and financial situations, created decreased capacity for social relationships, was responsible for sadness due to reflecting on food insecurity, fueled a feeling hopelessness or undeserving of help and led to frustration with their academic institution for not providing enough support(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5). While these themes illustrate how food insecurity may adversely affect students, the extent to which students experiencing marginal food security might have overlapping or dissimilar experiences as food security insecure students is unclear, as by definition they are not experiencing as severe food challenges.

In the current study, we interviewed thirty students about their experiences with marginal food security. The study aimed to identify themes from student interviews about their experiences with marginal food security and elucidate its impact on their health and academics.

Methods

Recruitment announcements were send out via email and school list-serves, flyers were posted around campus and student research assistants on several occasions would walk around campus with flyers in June 2019. Study inclusion criteria were as follows: current student at the university, ≥ 18 years of age, owning a mobile phone capable of accessing the internet and currently experiencing marginally food insecurity, as assessed by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Adult Food Security Survey Module(12). Students had to have a mobile phone capable of accessing the internet so they order food from the meal delivery service in any situation and did not have to be near a computer. The Adult Food Security Survey module asks participants to indicate how often certain statements represented their food situation in the last 12 months. Example statements include ‘I worried whether my food would run out before I got money to buy more’, and ‘The food I bought just did not last, and I did not have money to get more’. Students completed the online screening tool and those who met the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. We interviewed thirty students as previous studies interviewing college students about food insecurity reached saturation at twenty-five and twenty-seven students(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Henry11) . Written informed consent was collected from all study participants and the study design was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the university.

Demographic and academic information was collected from participants via an in-person survey after they agreed to participate in the study. This short self-administered questionnaire was completed in the presence of the interviewer before the interview began, and the participant was instructed to ask questions if they had any while filling out the form. Participants were then interviewed in-person in a private location on campus by one of two experienced interviewers (NO) and (RG). The semi-structured interview guide was based on that by Meza et al. (Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5), they had developed a questionnaire in consultation with food security experts, and we used that questionnaire as a basis for the guide we used in our study. Interviewers conducted practice interviews with student researchers to further develop prompting questions and to get feedback on clarity and respondent burden. Interviews were led by researchers and took between 8 to 59 min to complete, and averaged 17 min. The questions were designed to study the challenges associated with students’ food situations, their feelings and how their food situation affected their psychosocial health and/or academics. We added additional questions that were addressed in Henry and Daugherty’s work about the participants’ food environment and what they might ask the school to do to help them with their marginal food security (online supplementary material, Supplemental Table 1)(Reference Daugherty, Birnbaum and Clark10,Reference Henry11) .

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and later transcribed verbatim by (JS), (MP) and (ER). Themes were identified via an inductive approach by five researchers (JS), (MP), (ER), (AA) and (RG). The first three transcripts were coded as a group as a pilot test to standardise the coding process and resolve any questions. Subsequent transcripts were coded by a single researcher. Each coded transcript was then reviewed by two other researchers independently for inter-rater reliability. Regular weekly coding meetings were held and documentation of coding decisions was maintained to track questions and ultimate decisions for transparency. All coding was conducted in Dedoose (version 8.3.17). Themes were identified as a group by analysing the code co-occurrence chart in Dedoose, including the frequency at which study participants discussed similar topics.

Results

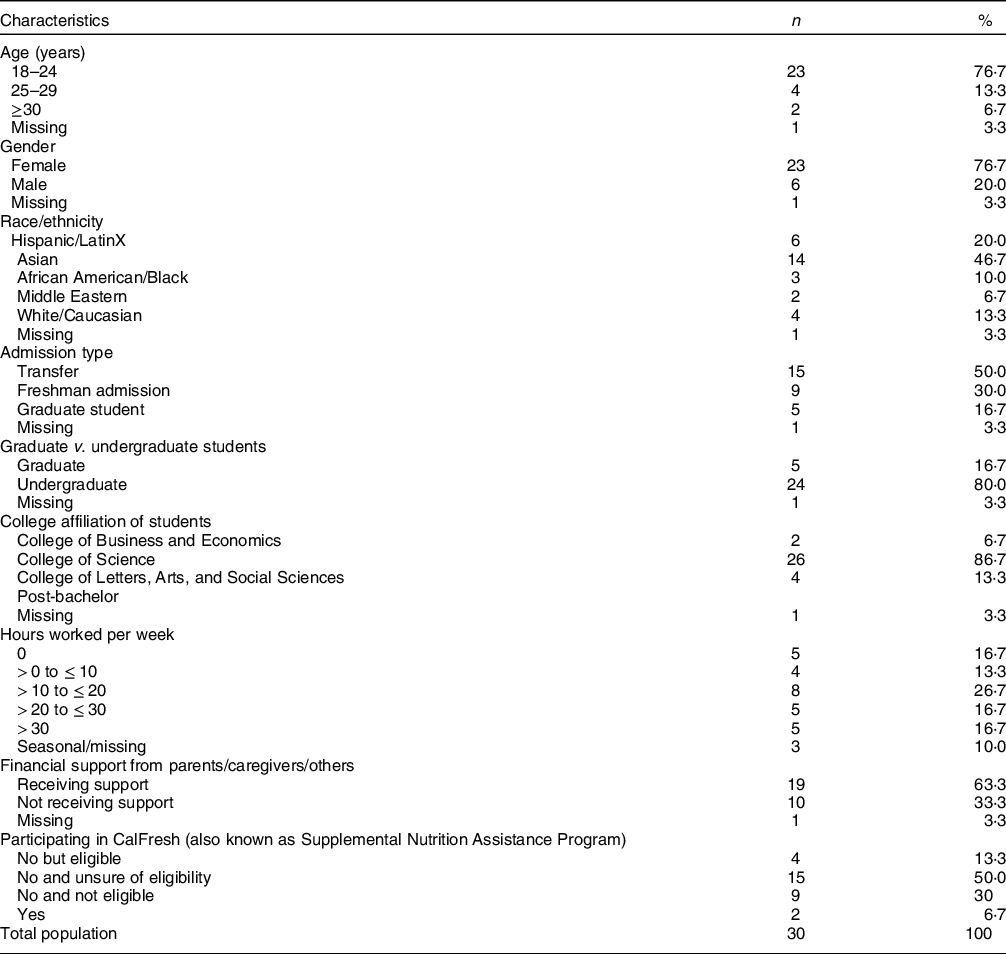

Participants in the study were predominantly undergraduates from the College of Science. A majority of the sample was female (76·7 %) and about half of participants identified as Asian (46·7 %) (Table 1). CalFresh, known federally as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, is the largest government food programme in California and provides monthly food benefits to participants with lower incomes(13). Half of students were unsure if they were eligible for CalFresh and while almost all participants indicated they had the equipment that they needed to cook, about a quarter of students stated they did not have adequate space to store food (Table 2). When surveyed on whether or not marginal food security affected their health and academics, 22 (73·3 %) of students reported that it affected their health and 20 (66·7 %) said that it affected their academics.

Table 1 Characteristics of student study participants (n = 30)

Table 2 Participant responses to questions about their food situation

* A campus programme that assists students with food, housing, emergency funds and other resources.

During the in-person interviews, students discussed how marginal food security affected their diet, mental and physical health, and academics. Key themes that emerged included trade-offs, insufficient time, stress and anxiety, self-perception, motivation and not fully participating in their academics (Table 3). Regarding diet, many students discussed purchasing foods based solely on price resulting in the consumption of more unhealthy foods, and also discussed not having enough time to procure, cook or eat food. Regarding mental health, students discussed having stress and anxiety, poor self-perception and a lack of motivation. Physical symptoms of marginal food security included fatigue and headaches, and to a lesser extent concerns about weight and the experience of hunger pains. Students discussed how their diets and the physical and mental consequences of marginal food security made it difficult for them to fully participate in their education, and in particular led to an inability to focus. Students had varying ideas regarding what the university could do to help the campus community with their food situations. Themes are described below in greater context with an accompanying quote to illustrate the theme.

Table 3 Themes and example quotations from thirty student participants

Purchasing trade-offs lead to unhealthy diets

Students frequently reported opting to purchase fast foods or less healthy food options due to price. Many reported juggling and managing bills for other basic needs and tuition in addition to food, and that saving money on food was a necessity. One student discussed needing to restrict spending on food, so she identified cheap foods that could get her through the day, such as frozen burritos. Another student stated that when buying food on campus, she would buy fries because it was not worth it to buy other more expensive foods available on campus. One student mentioned: ‘… sometimes food kind of falls last or healthier options fall last and you kinda get into the habit of oh I’ll just go and run to McDonald's and eat off of a dollar menu today or oh I’ll eat all this pasta because pasta is a dollar and veggie noodles are 5 dollars, 2 for 5 on a good day’. Participants also mentioned purchasing dry pantry staples, such as bread, canned goods and pasta because of their long shelf-life and versatility.

Having insufficient time to acquire, procure or eat food

Students consistently mentioned they did not have time to cook, procure or eat food. For example, students who worked while going to school often mentioned the challenge of having to rush in between their workplace and the university while also needing to eat or get food that would be eaten at a later time. For example, a student discussed skipping meals because of long lines and also not having a space to eat food on campus. One student mentioned that eating would take away time from her studies. One student related her experience navigating her packed schedule, saying: ‘Being a science major, I cannot even eat in class because you’re in a lab. So to eat, for the summer per instance, I have organic chemistry tour. I have a ten minute break in between lecture and lab so there’s not really time to eat. You can eat before or you eat after. And I’m in class almost til 1. So it’s like a 5 h chunk where it’s like you don’t have time to eat. And if you do you’re stepping out of class and you’re missing something. And so it’s kind of like “where am I gonna put my food, we can’t have it out [in] lab, we’re not supposed to eat in lecture.” So I think it’s just that and so by the time I get home I’m starving but I don’t wanna cook anymore so I’mma just go and run to get something to eat’.

Feeling stress and anxiety over food

Most students mentioned that food or thinking about eating healthy food when they did not have money for it was an added stressor, and became a bigger source of stress when neglected for an extended period of time. One participant relayed their worries about her future health saying: ‘There are people in my family who have diabetes and have had heart failure. And I do worry about that and It kinda gives me like a stress it’s like, “Okay well I kinda have to eat kinda like junk food just to get by.” But then it’s like I’m kind of compensating my future health and I get anxious about it. It’s like how much longer until something happens to me’.

Poor self-perception

In some of the interviews students identified a shift in the way they felt mentally after they ate poorly. They first expressed that they felt better and happier about themselves when they ate healthier food. Though students who mentioned that they ate unhealthily had thoughts related to gaining weight, which made them feel bad about themselves. In regard to their varying diet, a student said:

‘Yeah I feel better when I eat healthy. I don’t know, mentally and then physically because I know like oh I had a salad today or I ate some vegetables or something. Like I do feel better and you feel lighter and not like eating pork or beef and or something and you just feel down and like you feel it in your body. So when I do eat healthier things I do feel better rather than the unhealthy stuff.’

Marginal food security, fatigue, headaches and more other physical symptoms

Many students reported physical symptoms such as headaches, feeling less energised, sluggish or bloated due to their food situations. About half of the students attributed these physical symptoms to missing meals throughout the day or eating unbalanced diets. Some students reported feeling hunger pains and headaches which distracted them from doing school work. In regard to skipping and altering her meals, one student said: ‘Like recently, I’ve been like really groggy because like you know, you’re not getting the right meals and it’s just it makes you feel really bad. I just don’t like it and it gives you like, headaches and it doesn’t wanna make you do anything’.

Marginal food security leads to lack of focus and participation in class

The majority of students in the study reported that their academic performance was negatively affected by their food situation. Students reported that when they ate badly or skipped meals, they were less able to pay attention and focus in class. A student mentioned how the need to eat a better diet added to her stress, and she reported that when she felt stressed, she did not go to class because she felt that it was a waste of time to go if she could not focus. Another handful of students mentioned that their unhealthy eating habits would lead them to rest rather than do their school work. A student spoke of this issue, in response to whether their food situation affected their academics: ‘Yeah because there are days where I feel I’m not, I’ve just eaten something which is not all healthy and I can see that I don’t feel good, I can’t sleep, I can’t study well. But yeah there are days like this’.

Food on campus

Most students felt that the campus was not providing them with healthy options, and the few healthy options available, including the eatery on campus that sold salads, were cost prohibitive. Because of this, they often report resorting to the cheaper alternatives on campus such as fast food restaurants, as several students mentioned they frequently ate off of Taco Bell’s dollar menu. When discussing what the university could do to help marginally food secure students, many students mentioned having low cost healthy options. One participant said,

‘I just feel like sometimes the best thing [our campus] could do is maybe try to lower the prices of things if possible. I just feel like it’s kind of like a crunch for a lot of students cuz like I know we have the market on campus but the fruits there are like really expensive like a bowl of strawberry thats this big [participant put one hand in another and cupped them] is like almost five dollars I think that it’s a really ridiculous price to pay.’

Discussion

The current study was the first to our knowledge to interview college students with marginal food security about their experiences. By adapting an interviewer guide generated by food security experts in a previous study, this qualitative research provides context for recent quantitative findings associating marginal food security with poor health and academic outcomes.

Past quantitative and qualitative research suggests that experiencing food insecurity is negatively associated with academic performance(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Henry11,Reference Goldrick-Rab, Baker-Smith and Coca14) , and in the current study approximately two-thirds (66·7 %) of students reported experiencing marginal food security affected their academic performance. Those who indicated that marginal food security did not affect their academics often still acknowledged they had food challenges. This is a theme observed in Henry’s study(Reference Henry11), where four of nine Black students indicated that their food insecurity did not affect their academics, one saying that ‘It’s mind over matter, your body adapts to hunger’. This also indicates the use of coping strategies around food security among college students, highlighting the desire for good academic performance over the need for food. Of the students who indicated that marginal food security affected their academics, the predominant themes included the mental trade-off between focusing on food or academics and the consistent mention of wanting to rest or feeling tired after eating poorly, which were both also observed among the largely food insecure students in the study by Meza et al. (Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5). The current study suggests some students with marginal food security face similar challenges in achieving academic success as food insecure students.

Past research also suggests that experiencing food insecurity is negatively associated with health(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Henry11,Reference Goldrick-Rab, Baker-Smith and Coca14) , and our results support this finding, with a majority of students (73·3 %) experiencing marginal food security reporting effects on their health. Many students discussed headaches and feeling sluggish in response to missing meals or changes in their diets. More students discussed the mental health implications of marginal food security, and consistent with Meza et al. and Henry et al. (Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Henry11) , discussed feeling stress and anxiety surrounding food, a lack of motivation and feeling bad about themselves when they are not eating or eating what they consider healthy. While our data are only from a small sample (n 30) of college students, our results suggest students with marginal food security may be confronted with health challenges that are similar in nature to food insecure students, though future research is needed.

The large proportion of students that were marginally food secure that reported impacts on their health and academics suggests that some students who are marginally food secure should not be considered food secure, who by definition are adults who have no concerns or anxiety about consistently accessing adequate foods(2). The majority of students with marginal food security shared experiences similar to those of their food insecure counterparts(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5,Reference Henry11) . If campuses are considering marginally food secure students as students who have no food challenges, we may underestimate the positive effects of interventions that aim to improve food security status of students, such as campus food pantries and meal swipe programmes.

While there is much overlap in findings between marginally food secure students in our study compared with those conducted on food insecure populations, there were some differences.

Unlike quantitative analysis done by Meza on food insecure college students, the students in the current study experiencing marginal food security largely did not express anger at their institution for not providing enough resources, jealousy or resentment of other students who were food secure, or concern about disappointing their families(Reference Meza, Altman and Martinez5). While some students did mention not attending social activities and participating in campus life in the current study, this was not frequently cited unlike the study by Henry et al.(Reference Henry11). Findings could reflect real differences between students who are marginally food secure compared with those that are food insecure, or it could be a result of different prompts, differences in the student body makeup by race or by socio-economic status, or school culture.

Past research suggests our findings are in part due to misclassification bias, as the adult food security tool has not been validated for the college student population(Reference Ames and Barnett15–Reference Nikolaus, An and Ellison18). Indeed, in the current study we had students who reported their food security status did not affect them in any way, and others who reported skipping meals and truly struggling with eating enough food, which are in line with high food security and food insecure statuses, respectively. While misclassification is likely, no alternative food security assessment for college students has been widely adopted in the field. Subsequent research is needed to identify a validated food security questionnaire for college students.

There were several additional limitations to our study. First, we used a convenience sample of students from a single public university which greatly reduces our generalisability to other students and campuses. Our study population was representative of the university population, although there was over-sampling from certain colleges/majors and under-sampling in some race/ethnic groups. Our recruitment and interviewing were during our summer semester which may have impacted which students were available during this time period. We also conducted interviews with participants upon enrollment in the study, so the opportunity to develop a strong rapport with the participant was limited, which may have made the students less forthcoming in discussing implications of their food security status. Additionally, due to our semi-structured interviews, we cannot conclude, just because a thematic consensus did not emerge across students, that the students do not share these sentiments. Yet, findings are notable and have implications for how higher education institutions can better support marginally food secure students.

Conclusion

Marginal food security can potentially diminish students’ capacity to learn and succeed in their coursework, as well as to develop healthy food habits in their often formative college years. Students who are marginally food secure should not be grouped with students who have high food security, as doing so not only creates a heterogeneous category of students in regard to struggling to access food but also obscures their unique challenges. While there were overlapping themes found between previous research on food insecure students and our results from marginally food secure students, we identified several notable differences. This research underscores evidence that suggests marginal food security can inhibit college students’ personal, academic and professional growth. Further research is needed to support interventions and mechanisms to support marginal food secure students in achieving a greater level of food security.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: N/A. Financial support: This research was supported by a basic needs grant from the California State University Office of the Chancellor, the Health Sciences Department at Cal State East Bay and the Center for Student Research at Cal State East Bay. Conflicts of interest: None. Authorship: R.J.G., L.M.W., A.E., D.I., S.T., N.O. and K.C. designed the research. R.J.G. and N.O. conducted interviews, E.S.R., M.M.P., J.K.A.S. and R.J.G. analysed data and all authors helped in preparing the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The current study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving research study participants were approved by the California State University, East Bay Institutional Review Board. Written and verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects/patients.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980021001300