Introduction

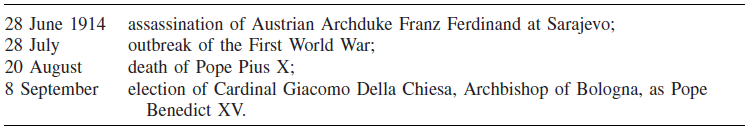

Let us begin with some dates to set the context:

A Pen Portrait of Pope Benedict XV

As was always the case until 1978, Pope Benedict XV was an Italian. He was born Giacomo Della Chiesa in Genoa, in 1854. After his ordination in St Peter's, Rome in 1878, he entered the Vatican diplomatic service. He served in the papal nunciature or embassy in Madrid from 1883 to 1887 and then in the Vatican under his boss, the Secretary of State, Cardinal Rampolla Del Tindaro. In 1901 he became the Under Secretary of State. The death of Pope Leo XIII and the election of Pope Pius X in 1903 caused him many problems because Rampolla was dismissed and replaced by Rafael Merry del Val who was Della Chiesa's junior in age and they did not get on well. In consequence, in 1908 Della Chiesa was effectively exiled from the Vatican and sent to the city of Bologna as its archbishop. This “exile”, as it happens, served him well: he was “humanised” by the experience of the pastoral care of his diocese, the fourth largest in Italy. He also came face to face with a phenomenon, the emerging Marxist revolutionary Socialist Party and its workers’ and peasants’ unions, whose rapid growth during the First World War would cause him much anxiety and influence his efforts to bring about peace.

The First World War and the Conclave

After the death of Pope Pius X on 20 August 1914, the conclave called to elect another pope in the following month faced a situation in which millions of Catholics were fighting on both sides of the war. This terrible division between Europe's Catholics was brought home to the assembled cardinals by declarations from German, French and Belgian Catholics justifying their governments’ decision to go to war.Footnote 1 The priority of the cardinal electors was to find someone who was diplomatically savvy and hopefully acceptable to all the warring powers. Though there was an attempt to stick to the policies of Pius X by promoting the candidacies of, first, Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val, Pius's Secretary of State, and then Cardinal Domenico Serafini, Giacomo Della Chiesa was the front-runner from the start, precisely because of his balanced blend of curial, pastoral and, above all, diplomatic experience. The war ruled out other candidates: in September 1914 Italy was still neutral so the war reinforced the tendency to elect an Italian, but Cardinal Domenico Ferrata's nunciature at Paris and Cardinal Agliardi's in Munich and Vienna “disqualified” them. There was resistance to Della Chiesa's election on the part of some cardinals from the Central Powers, though since Pius X had abolished the veto by secular rulers, there could be no serious attempt to influence the conclave.Footnote 2 However, it should be remembered that diplomatic questions, the papacy's relations with powers at war, were not the only issue at stake in the 1914 conclave. The question of the legacy of Pius X in other areas was also a deciding factor. Thus, the election of Benedict XV should be seen as a rejection of a large part of that legacy and, in particular, the excesses of the anti-Modernist campaign conducted by Papa Sarto.Footnote 3

The first appointments made by a freshly-elected pope, including that of Secretary of State, are usually a key indicator of the direction of the new pontificate. Benedict's “sacking” of Merry del Val was hardly a surprise and indicated his determination to break with the policies of his predecessor, especially in the diplomatic field. The appointment of the elderly Ferrata was a surprise and could only mean that Benedict wished to restore relations with France and thus close the unfortunate chapter written by Pius X and Merry del Val. But Ferrata suddenly died within weeks of his appointment and Benedict replaced him with Cardinal Pietro Gasparri, his old friend and colleague.Footnote 4 Gasparri was much same age as Benedict and had had the same sort of experience and formation in Vatican diplomacy, so the two men undoubtedly formed an ideal “team” but the pope would always have the last word. What Gasparri lacked, however, was pastoral experience, whereas Della Chiesa had been for seven years Archbishop of Bologna, one of the most difficult and turbulent cities in Italy.

Papal Peace Diplomacy

At bottom, Benedict's peace-making and humanitarian efforts between September 1914 and November 1918 were motivated by a deep revulsion at the “useless slaughter”, as he described it in his Peace Note of 1917.Footnote 5 He was particularly outraged by the new methods of waging war that had been introduced by the belligerents, like the horrors of trench warfare, the torpedoing of passenger ships and merchant vessels, and the aerial bombardment and shelling of cities with their civilian populations. Even though Catholics on both sides were invoking “just war” theory in justification of their participation in the conflict, Benedict seems to hint in his encyclicals that no war could be just in the circumstances of total war.

Benedict was undoubtedly inspired by an overwhelming sense of Christian charity and compassion but there were other considerations at work. Italian papal historian Carlo Falconi has argued that Benedict's wartime peace diplomacy was also motivated by a profound pacifism:

A man who…in June 1916 refused to approve the entry of a Catholic, Filippo Meda, into the… [wartime Italian] government and would never allow chaplains to appear in the Vatican in their military uniforms…is bound to be an unqualified pacifist.Footnote 6

Benedict often talked about the “suicide of civilised Europe”, which he feared would result from the war, i.e. economic, social and political breakdown, which was, of course, precisely what happened in a number of countries at the end of the war.Footnote 7

In his first public statement six days after his election, Ubi primum, Benedict, while stigmatising the war as God's punishment for sin, called upon the warring powers to lay down their arms and talk peace.Footnote 8 He repeated his plea in his first full-blooded encyclical, Ad Beatissimi apostolorum, of 1 November 1914.Footnote 9 By then the First World War had already settled into it a long, bloody war of attrition, especially in the trenches of the Western Front. As pope, Benedict inevitably attributed the conflict to man's falling away from God and rejecting Christ and his Church.Footnote 10 But the encyclical also made the astute observation that “Race hatred has reached its climax”.Footnote 11 Benedict was thus among the first to perceive that international affairs in Europe were being influenced by ideas of a Social Darwinian racial struggle, principally between Teuton and Slav, that is Germans and Russians. Though in Ad Beatissimi he also urged “Surely there are other ways and means whereby violated rights can be rectified”,Footnote 12 he did not at this stage offer any concrete, practical bases for a negotiated peace.

From 1915 onwards, however, he took several diplomatic initiatives to bring about peace, or at least stop the war spreading. In April and May 1915, for example, he tried to act as an intermediary between Austro-Hungary and Italy to prevent the latter from declaring war on the former, and in July of the same year, in his “Exhortation”, he made another call to the powers to negotiate, making one of his more poignant statements – “Nations do not die” – a clear reference to the fate of Belgium now almost entirely under German military occupation.Footnote 13 Shortly before the publication of this appeal, the Vatican had been involved in an attempt to negotiate peace between Belgium, France and Germany premised on the restitution of Belgium, which failed due to British intransigence.Footnote 14 In late 1916/early 1917 Benedict tried to act as a channel between some of the Entente powers and the new Austrian Emperor, Karl I,Footnote 15 and in the spring of 1917 he appealed to President Woodrow Wilson in an effort to stave off American entry into the war.Footnote 16

As the war progressed, the Vatican Secretariat of State found itself in the awkward position of being the recipient of dozens of complaints from both sides against “war crimes” allegedly committed by the others.Footnote 17 The Holy See did not possess courts of law competent to operate as the Nuremburg Tribunal and the International Court of Crimes against Humanity would later do. In any case, to have pronounced one way or another on alleged war crimes would have undercut the Vatican's claims to neutrality. Yet this did not prevent Benedict from conducting a correspondence with the Ottoman Sultan protesting about the massacres of the latter's Armenian subjects, the first major twentieth-century genocide, and with the Sultan's allies, the emperors of Austria-Hungary and Germany.Footnote 18 As a result of this, Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) possesses the only statue of Benedict XV outside Europe.

Obstacles to the Success of Papal Peace Diplomacy

There were several impediments to the success of the Vatican's peace-making role during the First World War, some self-imposed. In the first place, it took time to escape the diplomatic isolation in which Pius X had left the Vatican. It is no accident that in the most recent and authoritative analysis of the causes of the First World War by Cambridge historian, Christopher Clark, there is no mention of either Pius X, Merry Del Val, the papacy/the Holy See or the Vatican, or even the catholic Church….Footnote 19 Gradually, the exigencies of war broke this down as both belligerent powers like Great Britain, and neutrals like Switzerland and the Netherlands recognised the potential peace-making role that Benedict could play. They established or re-established diplomatic relations with the Holy See, which had declared itself both neutral and impartial in the conflict. Nevertheless, the verdict that J.D. Gregory, who served in the British legation to the Holy See between 1914 and 1916, passed on Benedict and Gasparri, “the Vatican is a fifth-rate diplomacy”, was probably shared by most other diplomats after the death of Pius X and for some years to come.Footnote 20

The physical location of the Holy See inside Italy, with which it had no diplomatic relations, was a further handicap. When Italy did go to war against Austria-Hungary and Germany, the embassies to the Holy See of those countries were banished from Rome to Lugano in Switzerland, hampering diplomatic communication with those powers. Furthermore, as American historian David Alvarez has pointed out, during the First World War the Vatican possessed no communications security. Since the Italians at this stage regarded the Vatican as part of their territory, police informers were everywhere, even penetrating the Secretariat of State and Vatican mail. Telegrams were routinely intercepted by the Italians, and the Italian secret service had broken all the Vatican's diplomatic codes.Footnote 21 Sydney Sonnino, Italy's foreign minister, made the things even more difficult for Benedict by insisting on the insertion of a clause into the Treaty of London of 1915 (which defined the terms whereby Italy joined Britain, France and Russia in the struggle against the Central Powers) precluding the pope's participation in an eventual peace conference.Footnote 22

There was a self-imposed problem: the Holy See under Benedict had its own interests, its own “war aims”, so to speak, so it could not really be entirely “impartial”. Thus it hoped to benefit from any subsequent peace treaty by regaining at least some of the territorial sovereignty of the popes that had been lost when Italian troops entered Rome in September, 1870. It also had much at stake in the survival of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the last Catholic great power in Europe and the bulwark against Orthodox Russia. The fear of a revival of Orthodoxy induced Benedict's Secretary of State, Cardinal Gasparri, presumably with Benedict's consent, to try to persuade the German High Command to make special efforts to halt the Russian advance on Constantinople in April 1916.Footnote 23 And as late as November 1918, Benedict and Gasparri attempted to win American support to prevent the complete military defeat and disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.Footnote 24

Humanitarian Relief

Benedict's peace diplomacy went hand in hand with his efforts at humanitarian relief. In December 1914 Benedict committed the Vatican to an array of papal relief work, which was to some extent comparable with that of the International Red Cross. Its principal focus was POWs, but also civilians. By the end of the war in November 1918, the “Office for Prisoners”, located in the Vatican's Secretariat of State, had dealt with a staggering 600,000 items of correspondence, including 170,000 enquiries about missing persons, 40,000 appeals for help in the repatriation of sick and severely wounded POWs, and the forwarding of 50,000 letters to and from prisoners and their families.Footnote 25 The Vatican arranged for food parcels and other goods to be delivered to POW camps and for sick and wounded POWs and civilians to convalesce in the hospitals or sanatoria of neutral Switzerland.

Achieving these results meant patient diplomacy to get around the obstacles put up by the warring powers, most notably Italy. Even more difficult was persuading the powers to let papal food relief convoys past their front lines – the Vatican was involved in feeding famished children in Belgium in 1916 and large numbers of people in Lithuania and Montenegro in 1916/1917, Poland in 1916, Russian refugees in 1916, and Syria and Lebanon from 1916 to 1923. Benedict had a particular concern for children and so continued to appeal for money for starving children in Central Europe after the end of the war. Reggie Norton has rightly pointed out that he can thus be regarded as one of the founders of the Save the Children Fund.Footnote 26

The Peace Note, August, 1917

Benedict's boldest and most public attempt to stop the war, the Peace Note, came in August 1917, and the international background helps to explain why he published it when he did. As early as 1916, it had become clear that various groups in America and Europe were looking to the pope to give a lead and he received visits in the Vatican from some of their leaders. By 1917, various international congresses were taking place to press for peace: Catholic parliamentarians from various countries met in Switzerland, representatives of Europe's Socialist parties met in Stockholm, and there were rumour rumours of a secret congress of freemasons to seek a peaceful way out of the war. As British historian A. J. P. Taylor, wrote, “The Summer of 1917 saw the only real gropings in Europe towards peace by negotiation.”Footnote 27 It was also true that by the summer of 1917 there were clear signs of exhaustion on the part of the warring powers. Czarism had collapsed in Russia in February/March as a result of the war, confirming Benedict's fears about the dangerous domestic consequences of the war. Austria-Hungary under the new Emperor Karl was also approaching exhaustion. And there was a series of very serious mutinies in the French Army after the failure of Nivelle's spring offensive. But probably what seemed to be the most propitious sign was the passing of a resolution in the Reichstag, the German parliament, in favour of “peace without annexation” in July 1917. Since Germany appeared to be in a strong military position on both the Eastern Front against Russia and in the Balkans, it was possible to imagine that her rulers might be persuaded that they could negotiate a peace deal from a position of strength.

Even before the Reichstag “peace resolution”, Benedict had sent Monsignor Eugenio Pacelli (later Pope Pius XII) as nuncio to Germany to sound out opinion there. He was well-received in military and governmental circles and returned with the feeling that the Germans were willing to negotiate seriously, even on such difficult issues as the evacuation and restitution of Belgium. So, on 1 August, the third anniversary of the outbreak of the war, the Vatican despatched the Peace Note to the heads of the belligerent powers, offering seven key proposals as a practical basis for negotiating peace:

-

(1) the re-establishment of the moral force of international law

-

(2) reciprocal disarmament

-

(3) international arbitration of disputes

-

(4) freedom of the seas

-

(5) reciprocal renunciation of war reparations

-

(6) evacuation and restoration of occupied territories, and

-

(7) the conciliatory negotiation of rival territorial claims.Footnote 28

The response of the belligerents was negative; neither side felt the moment was ripe for a peace initiative. The Germans, despite their courteous reply, felt that they were on a winning streak following the failure of Russian General Brusilov's offensive against them on the Eastern Front. Given its weakened and desperate state, Austro-Hungary could only follow in the wake of the German refusal. Above all, Woodrow Wilson gave it a cool, critical reception. This was decisive in ensuring the failure of Benedict's peace proposals because by now the United States had entered the war and the other Entente Powers were increasingly dependent on the American contribution to the war effort. Even before his government entered the war, the Calvinist president of the United States had been setting himself up as a new moral authority in the world. Benedict's only consolation would be that in content and formulation, Wilson's later “14 Points” was close to his own Peace Note.Footnote 29

Benedict was bitterly disappointed by the failure of the Peace Note, and public reactions to it. In France he was denounced as “le Pape boche” (boche is a derogatory word for the Germans). Even a priest in the Paris church of La Madeleine exclaimed, “Holy Father, we do not want your peace”. In largely Protestant Germany, Benedict had long been seen as “der franzöische Papst”, and in Italy some of the more intensely patriotic elements, led by a certain Benito Mussolini, renamed him “Maledetto XV” (a pun on his name: Maledetto means accursed in Italian, while Benedetto means blessed).

The Pope and his Secretary of State had gambled all the diplomatic influence of the Holy See in a major attempt to end the “horrible slaughter” and had failed. The episode demonstrated the limits of Vatican diplomacy: such diplomacy, based almost exclusively as it was on the moral authority of the head of the Catholic Church had limited influence on mainly Protestant powers like Germany, Britain and the United States, Orthodox Russia and Liberal-masonic powers, France and Italy.

Papal Peace Diplomacy: Benedict XV or Gasparri?

Clearly, Benedict relied heavily upon his Secretary of State, Cardinal Gasparri. This, and the fact that Pius XI retained Gasparri as Secretary of State until 1930, a decision unprecedented in the modern history of the papacy, raises an interesting question: how much of Benedict's diplomacy was really his own and how much was inspired by Gasparri? It is always difficult to decide how much of a pope's policy is his own and how much that of his Secretary of State. The authors of the entry for Gasparri in the Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani clearly believe him responsible for many of the most important diplomatic initiatives between 1914 and 1922.Footnote 30 My judgment is that papal peace diplomacy during the First World War was a synthesis of Benedict's great moral passion and Gasparri's worldly pragmatism.

The Legacy of the Peace Diplomacy of Benedict XV

The achievements of Benedict's diplomacy were considerable, despite the failures of his peace-making efforts. When he died in January, 1922, the process of restoring the effectiveness of papal diplomacy was well under way. Not only had Great Britain re-established relations with the Holy See in 1914, but Switzerland and also France did so in 1920, and relations with Germany, rather than Prussia, were established in 1924. Several other countries had also established relations, most obviously the “successor states” to the now vanished Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman and Russian empires, countries like the Baltic States, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia. Whereas the number of states with relations with the Vatican had stood at 17 on the eve of the outbreak of the First World War, at the time of Benedict's death in January 1922, it had risen to 27.Footnote 31 On this would be based the policy of negotiating concordats with individual countries that was initiated in Benedict's reign and successfully carried on by both Pius XI and Pius XII. And though there were not as yet formal diplomatic ties with Italy, the Holy See's relationship with that country was much more cordial than it had been in 1914. The way had been prepared by Benedict's diplomacy for reconciliation and the eventual solution of the “Roman Question” in 1929.

In fact, Benedict's legacy has lasted nearly one hundred years. He had irrevocably committed the Holy See to using its growing diplomatic resources not only for the defence of the Church's own immediate interests but also to a permanent peace-making and humanitarian role. His immediate successor, Pius XI, and the Secretary of State he inherited from Benedict, actively supported the search for peace and security in Europe in the 1920s, and Pius XI followed the same policy with Eugenio Pacelli as Secretary of State from 1930 onwards. When Pacelli became pope himself in March 1939 he used Vatican diplomacy in various attempts to preserve the peace right up to the moment that Hitler declared war on Poland at the beginning of September.Footnote 32 He also followed Benedict's example by setting up a Vatican Information Office to help trace missing POWs and civilians, and he promoted broader humanitarian relief efforts during the course of the Second World War and after.Footnote 33 Since 1945, successive popes have used their influence to assist in peace efforts – like John XXIII during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962,Footnote 34 Paul VI during the Vietnam War in the late 1960s,Footnote 35 and John Paul II during the Gulf and Iraq wars.Footnote 36 Thus the Holy See's ongoing, active diplomatic role in world affairs in support of peace is the most valuable and lasting legacy of Benedict's brief reign. We can, therefore, conclude that, inspired by Leo XIII, and assisted by Gasparri, Benedict XV laid the foundations of modern, twentieth/twenty-first century papal diplomacy.