[צו]פי ביא כה איינה צאפ׳סת גִאם רא

תא בנגרי צפ׳אי׳ מיי לעל פ׳אם רא

[מא רא] בר אסתאן׳ תו בסי חק כ׳דמתסת

אי כ׳אגִה [באז] בין בתרח׳ם ג׳לאם רא

חאפ׳ט׳Footnote 1

The immensity of the corpus and diversity of genres of Classical New Persian in Judeo-Persian garb is remarkable. Persian-speaking Jews have contributed extensively to Persianate literary production, both religious Jewish literatures, comprising a wide-ranging diversity of genres from translations of the Tanakh and rabbinic works to chronicles, lexicographies, religious poetry including translations of medieval Hebrew poems, as well as the large corpus of non-Jewish Classical Persian literature transcribed in Hebrew script. Jews started to write New Persian from its early periods. In fact, the earliest attestations of Early Judeo-Persian (8th to 12th century) are at the same time the oldest known literary monuments of New Persian.Footnote 2 The literary contribution of Persian-speaking Jews to Persian literature thus began already with the advent of New Persian literature in general. Nevertheless, the belles lettres genre of the non-Jewish Judeo-Persian Garšūni literary tradition is attested a bit later, specifically from the period of Classical Judeo-Persian (14th to 17th centuries) continuing up to the beginning of the period of Modern Judeo-Persian (19th to 21st centuries). Classical Persian poetry was a particularly fascinating and intriguing genre for Jewish audiences, which is evident in the extant Judeo-Persian manuscripts. Neither the special contents of these literary corpora are satisfactory exploited, nor are the collections entirely catalogued.Footnote 3 Detailed studies of this literature-in-transcription, as well as a comparison with literature in the common Perso-Arabic script are still a desideratum.Footnote 4 This article aims to undertake a preliminary survey of the extant Judeo-Persian versions of the Dīvān (‘Collected Poems’) of the celebrated Persian lyric poet Šams od-Dīn Moḥammad Ḥāfeẓ of Shiraz (ca. 715/1315–792/1390) and address some contextual aspects of its popularity among Iranian Jewry.

The Judeo-Persian Garšūni Literary Tradition

Jewish communities all over the world used to write a variety of languages other than Classical Hebrew in Hebrew script. This allographic tradition, which by no means is restricted to the Jewish communities, is known as ‘Garšūnography’, denoting the writing of one language in the script of another.Footnote 5 The diaspora Jewish communities of the ancient and pre-Modern eras, more specifically the educated members thereof, were mostly bilingual and broadly well-appointed to manage the multilingual and multicultural contexts in which the communities lived. These languages are conventionally named by means of the prefix ‘Judeo-’, for example the well-known Judeo-German (i.e. Yiddish) or Judeo-Spanish (i.e. Ladino),Footnote 6 Judeo-Arabic,Footnote 7 Judeo-Hindi/Urdu,Footnote 8 Judeo-Georgian, Judeo-Persian,Footnote 9 and so forth. These ‘Jewish varieties of languages’Footnote 10 profuse with aramaisms and hebraisms, namely a syncretism of Judeo-Aramaic and Hebrew with the languages of the local non-Jewish population. The shared common feature of writing a local language in Hebrew script was definitely a favoured and widespread way of both internal communication and manuscript production. The prominent role of the Hebrew Bible and the rest of the sacred tradition transmitted in Hebrew script, not only for Jewish worship but furthermore as a religious identification marker, bestowed a special place to the utilization of the Hebrew script beyond religious contexts. Hebrew was maintained almost exclusively for liturgical purposes while the active usage of a natural spoken Hebrew gradually faded among most diaspora Jewish communities around the world, including Iranian Jewish communities, until its revitalisation as everyday language in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Like other diaspora communities, Iranian Jews continued to learn and study biblical and Mishnaic HebrewFootnote 11 for religious purposes,Footnote 12 but wrote numerous varieties of Persian and other local languages and dialects in Hebrew script.Footnote 13 It was only beginning in the early 20th century, when Iranian Jews were becoming fully integrated into an Iranian middle class, that the use of Judeo-Persian has been gradually marginalized, above all under the homogenising pressure of modern school programmes using only the conventional Perso-Arabic script.Footnote 14

A typological survey of Judeo-Persian Garšūnography: Hebrew as the Target Script

As Jewish presence in Iranian lands dates back to the eighth century bce, evidence of language contact between Iranian Jews and the members of other diaspora communities is not surprising. The Hebrew scroll of Esther, as well as other Aramaic fragments found in Qumran (e.g. 4QTales of the Persian Court, the so-called proto-Esther), indicate that a considerable amount of Persian already existed in the language of Iranian Jews as early as the Achaemenid period (549–330 bce).Footnote 15 Utilization of Aramaic scripts for Iranian languages is attested from the 5th century bce, when Imperial Aramaic gained the status of chancery language of the Achaemenid Empire. As a result, the Aramaic alphabet was adopted in many regions for writing local languages. Material evidence however is only attested from the Parthian period (ca. 210 bce – 224 ce) onwards.Footnote 16 The allographic usage of Hebrew script for Persian, and to be more accurate for Judeo-Persian, is attested in the early periods of emergence of Early New Persian in the early Islamic periods.Footnote 17 It is a remarkable coincidence that the oldest written evidence of New Persian language is at the same time the earliest evidence of Judeo-Persian, in manuscripts and inscriptions containing texts of different genres, as well as memorial and tomb inscriptions, legal documents, biblical translations and commentaries, private and commercial letters, commercial notes, poetry, and historiographies from the eighth century onwards.Footnote 18 These texts originate from numerous Jewish centres in the Persianate world, from present day Iran and Afghanistan, to Central Asia and the Caucasus, and beyond up to Egypt, India, and China.Footnote 19

The major bodies of Judeo-Persian corpora from the medieval up to the pre-modern periods can chronologically divided into three phases. The first period is between 11th and 15th centuries, during which Khuzestāsn, Fārs, and specifically Bukhara flourished as centres of Jewish theological studies, especially of the Tanakh. The end of this period coincided with the blossoming of Judeo-Persian poetry in Shiraz and central Iran, which lasted from the 14th to the 18th century. Subsequently Bukhara again became the flourishing core of Judeo-Persian literature around the 17th century, following the migration of many Jews from the borderline the Ṣafavīds and Šaibānīd borders, until the 19th century.Footnote 20

The Turco-Mongol invasion of Iran and the domination of Īlkhānīd Mongols over the Middle East during the 13th and 14th centuries ce, dramatically changed the situation of many Iranian religious minorities.Footnote 21 For example, the invasions meant an end for the existence of many Zoroastrian communities, especially in North and North-Western Iran.Footnote 22 Despite the early religious tolerance and the alleviation of sanctions towards the Iranian Nestorian Christians, already all voices and traces of Iranian Christians terminate soon after the conversion of the seventh Īlkhān, Ġāzān Khān (1271–1304 ce) to Islam in 1295, and the majority of the dioceses in Iran vanished after the 14th century. The Mongol Īlkhāns re-introduced a heavy head tax for the Jews, Christians and Zoroastrians after their accession to power, which economically destroyed the surviving minority communities,Footnote 23 besides inducing the destruction of Jewish, Christian, Buddhist and Zoroastrian temples throughout the empire.Footnote 24 Jews and Christians continued to be treated ḏimmīs “protected people”. But in contrast to Zoroastrians, who followed a policy of self-isolation and marginalisation to remain as inauspicious as possible, Iranian Jews did not disappear from the administration of the Mongol state and continued to be present at the Īlkhāns’ courts and regularly took part in the intellectual, cultural, social, and political life of the Muslim majority.Footnote 25

The difficult financial and social conditions in the 13th century did not prevent the Jews from maintaining literary production. The corpus of Judeo-Persian literature from the period after the Mongol conquest of Iran is impressive, though barely studied. This is the time that Classical Persian Poetry occupies an important place within Judeo-Persian literary production. The epic-style poetry especially flourished among the Jews and a number of famous Judeo-Persian poets, such as Šāhīn (14th century), ʿImrānī (1454–after 1536), Bābāi b. Luṭf, Bābāi b. Farhād, and Binyamīn ben Mišāʾel (Aminā) translated and versified largely Hebrew Tanakh and Midrašīm, as well as numerous philosophical and theological treatises and books. Just to mention one, the famous Pentateuch versification of Maulānā Šāhīn-e Šīrāzī, known as tafsīr-e šāhīn ʿal ha-tūrā is one of the earliest masterpieces of this genre.

Classical New Persian Literature in Jewish-Persian Versions

The corpus of Judeo-Persian literature composed in the aftermath of the Mongol invasions of Iran in the 13th century is conventionally called ‘Classical Judeo-Persian’, which is in line with mainstream Classical Persian Literature, albeit in Hebrew script. Similar to the leading role of Classical Persian poetry in the medieval and pre-Modern Iranian literary tradition, the stature and significance of poetical genres, both epic and lyric is omnipresent within Classical Judeo-Persian literature. This is evident not only in the versified translations of the Tanakh, Midrašīm, and other religious works, but also in poetic historical narratives and most notably in the Judeo-Persian rendering of non-Jewish classical Persian masterpieces. There are a considerable number of Judeo-Persian manuscripts, mostly neither studied nor edited, which comprise collections of Persian poetry that is not specifically ‘Jewish’. A quick overview on these collections shows a wide variety of original compositions by Iranian Jews as well as partial and complete Hebrew-script transcriptions of major works of Classical Persian poetry. These corpora of individual classical Persian poems transposed by ‘transcriptions’ into Judeo-Persian have almost never been studied. Vera B. Moreen has recently introduced a Judeo-Persian manuscript of Ǧalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī's Mas̱navī-ye maʿnavī, which remains a unicum pending the systematic cataloguing of the large collection of Judeo-Persian manuscripts at the National Library of Israel, Jerusalem.Footnote 26 The corpora of Judeo-Persian transcriptions of mainstream Classical Persian poetry comprise a wide range of literary canonical works, mostly dated from the 16th century onwards. Beside genuine Judeo-Persian mystical compositions, there are a moderately large number of transcriptions of popular Persian mystical epic romances. Among others, popular works are the narrative epic romance of Ḫosro-o Šīrīn by Neẓāmā Ganǧavī (1141–1209) and Yūsef-o Zoleyḫā of the Ṣūfī poet Ǧāmī (1414–1492). Very popular were also the Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Saʿdī's Golestān “Rose Garden”, the Dīvān of Ṣāʾeb of Tabriz (ca. 1592–1676), the Dīvān of Šāh Neʿmatollāh Valī (d. 1431), founder of the Neʿmat-ollāhī Ṣūfī order), and poems ascribed to ʿAṭṭār.Footnote 27 Moreover, the Judeo-Persian collections contain a good number of poems composed by unknown or less celebrated poets of Jewish or non-Jewish origin. There are also a number of poems ascribed to Ḥāfeẓ, ʿAṭṭār, and other celebrated poets which do not appear in the standard editions of their collected works.Footnote 28

This list reveals, besides the works which were of interest to the Jewish community as well as those which seem to be missing, that for the mainly urban Jewish community, access to certain major literary works of the non-Jewish Classical Persian poetry was part of their intellectual participations to the daily Iranian Muslim life. This is also certified by various historical accounts about the community. Jewish poets such as Šāhīn, ʿImrānī, Bābāi ben Luṭf, and Bābāi ben Farhād, but also many others, were clearly literary agents of the Classical Persian poetical tradition and successfully tried their talent as Persian poets. So, it is actually not surprising that not only for them, but also for a good number of the Iranian Jewry who were familiar with the classical literature and poetry, the classical Persian poems were an important part of their intellectual affairs.

Jewish Ṣūfīs and the Mystic Classical Persian Poetry

Ṣūfism exerted a significant influence on Islamicate societies and most specifically from 9th century onwards centres of Islamic mysticism (ḫānqāh) gained currency all over the Iranian world. Variations of mystical views of the universe, life and truth became predominant and influenced Iranian philosophies and worldviews, which resulted a sort of preponderance of Ṣūfī expressions and terminology within Classical Persian literature. Already in the 13th century, the famous philosopher and mystic Abraham (Abū ʾl-Munā Ibrāhīm) ben Moses ben Maymon (1186–1237), son of the great Jewish legal authority and philosopher Moses Maimonides (1137–1204), tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to establish his own Jewish Ṣūfī ṭarīqa. Works of other Spanish Jewish philosophers and mystics, such as the Baḥya (Abū Isḥāq) ibn Paqūda's (1050–1165) Judeo-Arabic Kitāb al-Hidāya ilā Farāʾiḍ al-Qulūb “Guide to the Duties of the Heart” (usually dated 1081) played a direct role in the construction of Iranian Jewish mystical philosophy (see below).Footnote 29 He was a great admirer of Islamic Ṣūfism and introduced a series of innovations inspired by the Muslim tradition.Footnote 30 As already mentioned, at least one copy of the Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Šāh Neʿmatollāh Valī survives, which suggests a remarkable grade of fascination for the Neʿmat-ollāhī order. The Neʿmat-ollāhī Ṣūfī order (founded towards the end of the 14th century) enjoyed great popularity among other Iranian Ṣūfī orders and beyond. There is not much evidence to link Iranian Jewish Ṣūfīs directly with the Neʿmat-ollāhī order, beside this manuscript. However, there is another hint which might support such connections even if indirectly, which I will discuss below with manuscript heb. 28°5088. Both the Neʿmat-ollāhī as well as Sohravardīya (founded by Šeyḫ Šahāboddīn Soharvardī, d.1234) Ṣūfī orders were widespread in India as well and show interesting connections to Iranian Jewish Ṣūfism. Nevertheless, even if the Iranian Jewry never fully implemented Iranian Muslim Ṣūfism, however, certain aspects of Islamic mysticism which were in accordance with Jewish mysticism, and particularly Islamic mystic terminology, were quickly adopted in both intellectual and literary levels. Not to forget is that the sporadic participation of Iranian Jews in Ṣūfīsm was also part of the cultural complex of the acculturation of Iranian Jewry in the medieval and premodern periods.

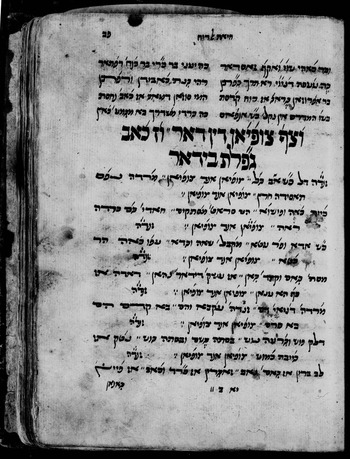

Among others, a learned merchant Jew from Mashhad, Mollā Yeḥezqel (Ḥizqīl/Ezekiel, also known as Nāmdār), who was also a teacher of Torah and Talmud, is known to have had a Judeo-Persian copy of Ǧalāl ad-Dīn Rūmī's Mas̱navī, from which he taught his favoured students, alongside the regular Jewish religious literature.Footnote 31 The account goes back to the period eight years prior to the violent revolt and forced conversions of Mashhadī Jews in 1839, known as allāhdād.Footnote 32 This stands to reason that the popular attractiveness of the Mas̱navī based on its numerous of Ṣūfī stories made it as a useful didactic reading. The popularity of Ṣūfī poetry, literature, and concepts can be more elaborated when we trace Ṣūfī-Jewish relations back. Ṣūfī motifs as a literary topoi is closely connected to the Classical Persian literature. Ṣūfī terminology and concepts have affected the literary language insofar that a separation between ‘genuine’ Ṣūfī and non-Ṣūfī thoughts seems to be almost impossible. These can be easily traced in the vocabulary of the almost all known Judeo-Persian poets. But the attraction of Ṣūfism within the Iranian Jewish elite learned community, goes beyond simple literary topoi. The interaction between intellectual Iranian Jewry and Ṣufism has a deeper intellectual background.Footnote 33 Specially the Mashhad was already turned to a centre of Jewish-Ṣūfi involvements since the Nāder Šāh partly resettled the Jewish community from Qazvin and Gīlān to Mashhad around 1746.Footnote 34 It is in this newly stabilised Jewish community that Yazdī Rabbi Simān-Ṭov Melammed (1823 or 1828), known by the pen name Ṭuvya, a prolific author, poet, philosopher, mystic and spiritual leader of the Jewish community in Mashhad flourished.Footnote 35 He composed many treatises, both in Hebrew and Judeo-Persian, among others azharot “exhortations” (1896), a multilingual treatise in Judeo-Persian, intermixed with verses in both Hebrew and Judeo-Persian, as well as a commentary to Pirqé Abot. But his major work, a mix of both Jewish and Ṣūfī philosophy and mysticism, is his philosophical-religious book Sefer Ḥayāt al-Rūḥ “The Book of the Life of the Soul” (1778),Footnote 36 a kind of commentary on the doctrine of Maimonides on the Jewish Diaspora and final salvation. Melammed conveys sincere respect and devotion to Ṣūfism in he repetitive refrain of his tarǧīʿband (strophic poem) in Ḥayāt al-Rūḥ entitled ״ ו'ז כ'אב ג"פלת בידאר ו'צף' צופ'יאן דינדאר/ vaṣf-e ṣūfīyān-e dīndār-e vaz ḫāb-e ġeflat bīdār “Description of the Pious Ṣūfīs roused from the sleep of neglect” (Ms. heb. 28°5760, fol. 82r-82v). This work of approximately 8,000 lines (prose and verse) was deeply inspired by the aforementioned ibn Paqūda's Kitāb al-Hidāya ilā Farāʾiḍ al-Qulūb [Ḥovot ha-Levavot]. Melammed's mystical enthusiasm admiration reads as follows (Fig. 1):

Fig. 1. The strophic poem of Simān-Ṭov Melammed entitled ו'צף' צופ'יאן דינדאר ״ ו'ז כ'אב ג"פלת בידאר / vaṣf-e ṣūfīyān-e dīndār-e vaz ḫāb-e ġeflat bīdār “Description of the Pious Ṣūfīs roused from the sleep of neglect”, from Ḥayāt al-Rūḥ, ms. heb. 28°5760, Fol. 82r. Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

Less than a century later, we encounter accounts of the secret Jewish Ṣūfīs of Mashhad, mentioned firstly by Joseph Wolff (1795–1862), a Jewish Christian missionary,Footnote 39 who arrived in Mashhad in first week of December 1831 on his way to Bukhara.Footnote 40 He obtained an audience with Prince Aḥmad ʿAlī Mirzā Rokn-ol-Molk (1804–1855), the governor of Khorasan in the early 19th century, immediately after his arrival in Mashhad. Prince Aḥmad ʿAlī Mirzā was the third son of the ruling King Fatḥ-ʿAlī Šāh Qajar (1771–1834) and Maryam Khanūm Banī Isrāʾīl (1770–1843), his thirty-ninth wife, who was of Jewish origin from Māzandarān and bore five other children.Footnote 41 Wolff was introduced by Aḥmad ʿAlī Mirzā to Mollā Māšīh ʿAǧūn (perhaps a reduction of Masīh Āqāǧān),Footnote 42 the chief of the local Jewish community, who was known as Mollā Mahdī by the Muslims and with the title Nasi (נָשִׂיא “prince, chief”) among the Jews. According to Wolff, the Jewish Ṣūfīs had followed the Muslim Mollā Moḥammad ʿAlī Yshkapate/Ashkeputi (probably ʿEšqābādī) as their moršed “(spiritual) guide or teacher”.Footnote 43 He gives some details regarding the manuscripts in the possession of the Mashhadī Jews, among others copies of the Persian translation of the Pentateuch (tora) and Psalms (sēfer tehillīm),Footnote 44 a Judeo-Persian copy of the Yūsef-o Zoleyḫā by Molānā Šāhīn, a Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, a Hebrew translation of the Quran,Footnote 45 as well as a copy of Ferdōsī's Šāhnāme and a copy of Rūmī's Mas̱navī.Footnote 46 It not specifically mentioned whether the latter two are Judeo-Persian transcriptions of the Šāhnāme and Mas̱navī, or manuscripts in Perso-Arabic. Despite Wolff's generally uncritical interest in manuscripts, I am inclined to suggest that again here Judeo-Persian manuscripts are meant. Wolff mentions the Jewish Ṣūfīs of Mashhad and the importance of the poems of Ḥāfeẓ and Rūmī among them in his both travelogues. In the report of his visit to Mashhad in 1831 he mentions how the Mashhadī chief Rabbi Mollā Mahdī presented him with a mystical interpretation of Ḥāfeẓ's poetry:

The wine, Mullah Meshiakh [i.e. Mollā Mahdī] observed, of which Hafiz sang, is the mystical wine of truth. Mullah Pinehas, Mullah Eliahu, Mullah Nissin, Abraham Moshe, and Meshiakh Ajoon [i.e. the same above-mentioned Mollā Mahdī], belong to the Jewish Sooffees.Footnote 47

And again, in the account of his second visit to Mashhad in 1844 as follows:

On my second arrival I heard more fully the history of the massacre [i.e. allāhdād] of the Jews. The Jews for centuries had settled there from the cities Casween, Rasht, and Yazd. They were distinguished advantageously by their cleanliness, industry, and taste for Persian poetry. Many of them had actually imbibed the system of the Persian Suffees. We heard them, instead of singing the Hymns of Zion, reciting in plaintive strains the poetry of Hafiz and Ferdousi, and the writings of Masnawee.Footnote 48

Beside all these historical accounts, a quick look through the extant Judeo-Persian manuscripts clearly testifies the admiration of the Iranian Jews for Ṣūfī poetry. The affiliation of not only the Jewish Ṣūfīs, but Iranian Jewry in general, with poems of Ḥafeẓ is in this context unsurprising.

Judeo-Persian Manuscripts of the Dīvān of Hāfeẓ

There are a good number of Judeo-Persian transcriptions of Classical Persian poets, which do not appear in their common standard editions. Even if most of the extant manuscripts seem to be too young to be valuable for critical editions, the edition and analysis of these ‘ghosts’ together with the clearly ascribed poems have never been undertaken, it remains open if and how the variations rendered in the transcription, might help to supplement the current editions of classical Persian poetry. The understudied Judeo-Persian Hāfeẓ tradition does not make an exception. Jes Peter Asmussen (1928–2002), one of the most prolific scholars of Jewish Persian literature, devoted a brief chapter of six pages in his Studies in Judeo-Persian Literature (1973) to a short comparative analysis of four poems from the two Judeo-Persian manuscripts Or. 4745 (now at the British Library) and Add. 16 in Det koneglige Bibliotek, Copenhagen.Footnote 49 In the following section, I trace the footsteps of Hāfeẓ poems within some Judeo-Persian collections. This overview is by no means an exhaustive list and is just a first step towards future studies.

There are many selections or single Judeo-Persian renderings of Ḥāfeẓ poems scattered throughout Judeo-Persian mixed collections and miscellanea. Vera B. Moreen records five manuscripts containing poems of Ḥāfeẓ out of 198 Judeo-Persian manuscripts of the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, namely ms. 1365.8; ms. 1423.32; ms 1453.18; ms. 1478.2 and ms. 5551.1, dated variously from 16th to 19th centuries from Iran and Central Asia (Bukhara):Footnote 50

• ms. 5551 (ENA II 76),Footnote 51 which is a Judeo-Persian rendition of ġazals, mostly by Ḥāfeẓ and Ǧāmī, dated to 16th or 17th century, Iran, 13 leaves. Paper (light beige); 14.5×9.7 cm.Footnote 52

• ms. 1365 (Acc 57458), a collection of various Hebrew and Judeo-Persian poems, dated 18th or 19th century (?) 240 leaves. Paper (mostly dark beige and some blue); very worn and stained at the deckle; 11.5×16.2 cm. In fol. 161r–161v, it contians a Judeo -Persian transcription of a poem by Ḥāfeẓ, titled חפיז כ׳וג׳ה “[A selection of] Ḫāǧe Ḥāfeẓ” (fol. 161r) not found in standard editions, followed by a quatrain.Footnote 53

• ms. 1423 (ENA 185), another collective manuscript, dated 1891? [Iran], 103 leaves. Paper (light beige); heavily stained; 10.5×16.7 cm, which in fol. 97r–98r contains a vocalized Judeo-Persian transcription of a ġazal by Ḥāfeẓ, entitled אין ג״זלי כונה חפיס .Footnote 54

• ms. 1453 (ENA 496), a Haggadah, containing Hebrew and Judeo-Persian texts, dated 19th century [Iran], 24 leaves. Paper (dark beige); water damage; ruled with ruling board; fol. 24 bound upside-down; 10.5×20.5 cm. Contains in fol. 24r a Judeo-Persian transcription of a ġazal by Ḥāfeẓ, entitled ג״זל חפט׳ .Footnote 55

• ms. 1478 (ENA 673), a collection of rabbinic narratives and Jewish Iranian tales, dated 19th century [Iran], 65 leaves. Paper (beige and blue); extensive damage; different sizes; ca. 22× 17 cm. In fol. 4r-5r and 8r/v contains three ġazals by Ḥāfeẓ, titled ג׳״זל חאפט׳ at the front matter.Footnote 56 ms. 1490 (ENA 1387 b 36), a mixed Judeo-Persian and Persian collection, dated 19th cent.? [Bukhara], 185 leaves. Paper (thick, beige); water damage; 17.2×10.4 cm. In fol. 139r–139v contains a Judeo-Persian imitation of a famous poem by Ḥāfeẓ. Furthermore it contains a Judeo-Persian rendering of a qaṣīde in form of baḥr-e ṭavīl by Zeynabī Samarqandī (fols. 140r–148r), as stated in the heading בחרי טביל מו זינבי צמרקנדי, imitating a famous poem by Ḥāfeẓ.Footnote 57

Beside the occasional selections or single Judeo-Persian rendering of Ḥāfeẓ poems within the miscellanea, there are also a remarkable number of survived copies of the whole Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ. Moreen mentions four copies of Ḥāfeẓ's Dīvān, kept at the Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem.Footnote 58 The enlisted manuscripts are ms. heb. 38°5106, possibly from the 16th century, ms. heb. 28°5088, dated to the 18th century and ms. Heb. 28°3418 as well as ms. heb. 38°5645, both from the 18th-19th centuries.

Putting aside the main texts contained in the manuscripts for a moment, though they certainly deserve an independent investigation, I want to take a closer look at two manuscripts of Ḥāfeẓ's Dīvān from rather a different point of view, using another kind of data available, namely the notes, colophons and material traces left by patrons, scribes, owners, and readers. Investigation of these sometimes arbitrary paratextual elements may allow us to reconstruct different facets of the production, circulation, and consumption of these manuscripts. In this perspective, the most interesting manuscript among the Judeo-Persian Ḥāfeẓ manuscripts from various collections is without doubt the manuscript heb. 28°5088.

Ms Heb. 28°5088

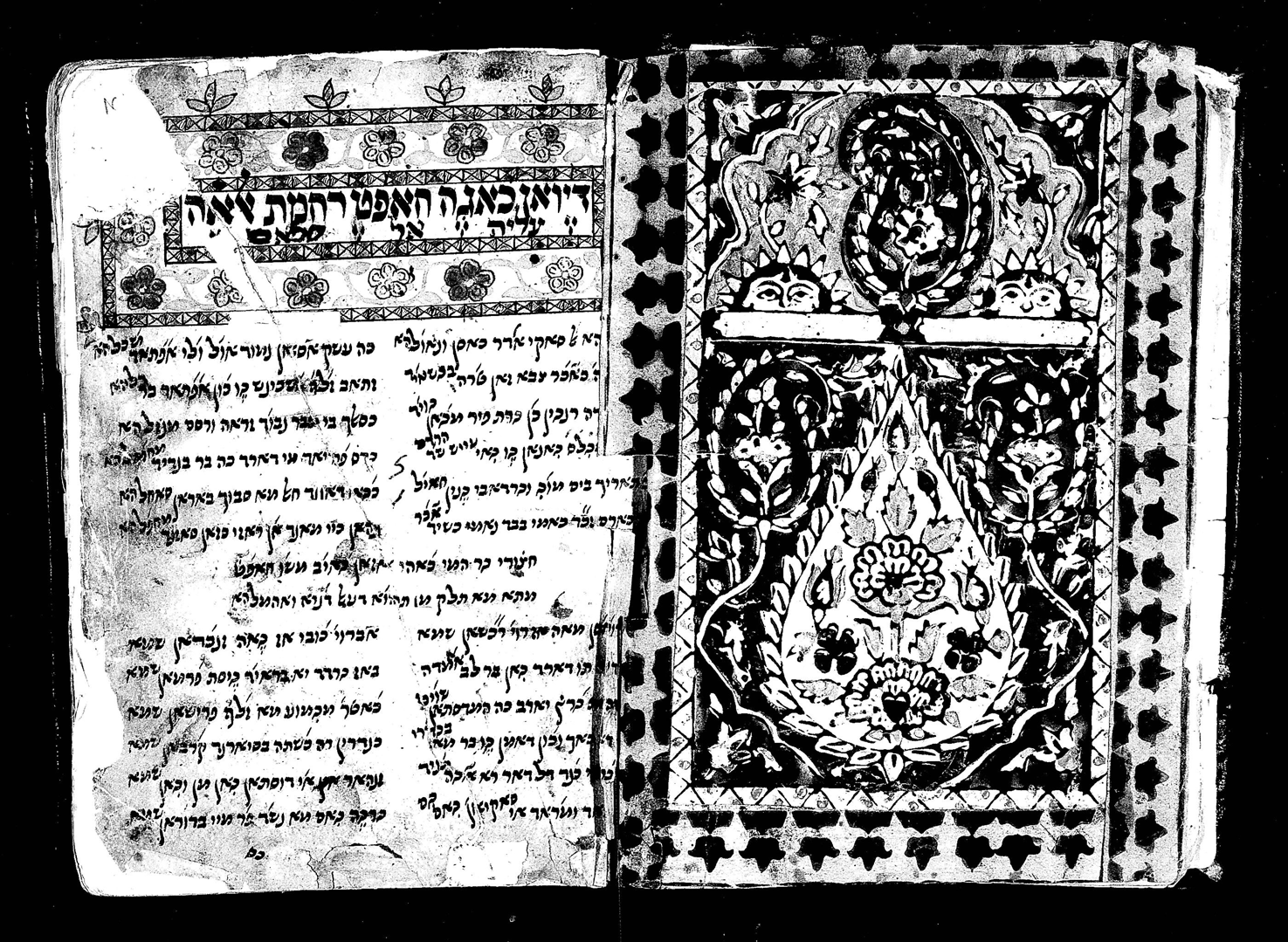

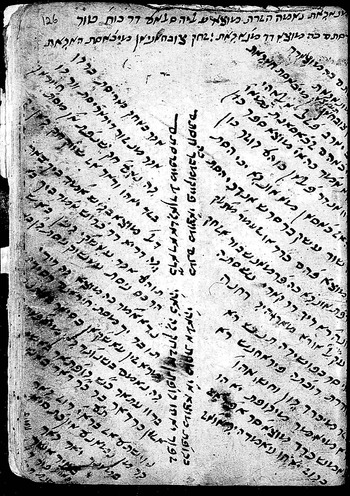

Ms Heb. 28°5088 is a 18th century Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, with the heading דיואן כאגה האפט רחמת ﭏאה עליה אל סלאמ in 138 pages and the format of 15v20 cm, is written on Western paper (inside watermark date 1792) and holds decorative motives of bote-ǧeġe (curved-top Cedar designs), flanked by two motives of Ḫoršīd-Ḫānūm “Lady Sun” on the initial page (fols. 1v-2r, Fig. 2). The manuscript comprises eighteen multilingual folios (124v to 138r) at the end of the manuscript, directly after the closing phrase תמת אל כתב, which are mostly secundo manus and relate to the various owners. The marginalia and back matter are in Hebrew, Judeo-Persian, Persian, and two ‘Indian’ scripts, and comprise selections of poetry and personal notes. The notes and selected poems added at the end of the manuscript give an interesting impression of the cultural background of its owners, and the geographical and intellectual exchange of the Judeo-Persian manuscripts of this genre. Among others the monāǧāt-nāme ascribed to ʿAṭṭār, described as מנאגאת נאמה הזרת מוצא עליה סלאמ דר כוח טור / monāǧāt-name ḥażrat mūsā ʿalayhe salām dar kūh-e ṭūr Footnote 59 “The intimate conversation of Moses, peace be upon him, in Mount Ṭūr” (fol. 126r, Fig. 3). Evidently the scribe uses the title of ʿAṭṭār's mas̱navī from ʾElāhī-nāme “Book of the Divine”, referring to the biblical Moses narrative. However, according to my knowledge, the poem is not to be found within the canonical collections of ʿAṭṭār's works. The scribe reveals his identity by using the title צעיר “young”, usually used for means of false humility by great Rabbis:

תמ. נוישתם אז בראי רוז גאר / גר מן נמאנם אין ךת […] במאנד יאד גאר … צעיר אשר … באוואלפור… שנת…

“Finished! [I've] written for the sake of vanity, this script […] will outlive me and remain as my commemoration, [written by] the young man, who […] Bavalpur […] Year […]”.

Fig. 2. Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms. Heb. 28°5088, Fols. 1v-2r. Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

Fig. 3. Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms. Heb. 28°5088, Fol. 126r. Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

The poetic formulation here is a well-known cliché of Persian colophons. Unfortunately, the year and the name of the scribe are illegible, but not of less importance, the location of the then-owner of the manuscript is clearly stated: the princely state of British India Bahawalpur in the Punjab province, today Pakistan. Bahawalpur state was founded in 1727 ce by the Muslim Navāb Ṣādīq Muḥammad Khān ʿAbbāsī I (1715–1742). The town and surrounding region, specially the neighbour historic city of Uch (Uuch Sharīf “Noble Uch”), which came under the control of the Bahawalpur princely state in 1748, is known for its Ṣūfī affairs and contains numerous tombs of prominent pīrs.Footnote 60 Uch is also closely connected with Sayyed Ǧalāl al-Dīn Boḫārī, known as Sorḫpūš (595/1198–690/1292), the renowned Central Asian Ṣūfī mystic, who migrated from Bukhara to Uch in 1244–1245, under Mongol rule. He was a Ṣūfī saint and missionary and a follower of Bahā-ʾod-dīn Zakarīyāʾ (577/1182–661/1262), Ṣūfī saint, scholarm and poet who established the Sohravardīya order of Baghdad in medieval South Asia.Footnote 61 Another note (124v) mentions also Multan, a city and capital of Multan Division located also in Punjab, today Pakistan. Like the nearby city of Uch, hosting a large number of Ṣūfī shrines, Multan was also a ‘City of Saints’, attracting congregations of Ṣūfī mystics from the 11th and 12th centuries onwards. The note (fol. 124v, Fig. 4) mentions a certain Rabbi Reuben Cohen ראובן כהן in Multan. Here again the title צעיר “young” is used for false humility, which suggests that the owner of the manuscript was a great Rabbi and probably a high-ranking community leader:

נוישתה שוד דר מולתאן ה' אייר שנת ת"קע"ד צעיר ראובן כהן

“Written in Multan, 5th of Iyar 5574 (April 25th 1814), the young Reuben Cohen”

Fig. 4. Detail from the Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms. Heb. 28°5088, Fol. 124v.

Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

The notes at the end of these manuscript here show remarkable connections to both major Ṣūfī orders of Neʿmat-ollāhī (mostly in Deccan)Footnote 62 as well as Sohravardīya (in Punjab).

Interestingly enough, the manuscript contains two notes in two different ‘Indian’ scripts (fol. 129r, Fig. 5). The first line seems to be in Landa, an old italic that was common in what is now Pakistan and is the basis of the script of the second note below, which could be an italic Gurmukhi (for Punjabi) or Khudabadi script, the pre-Arabic script for Sindhi. It shows clearly that at a certain time the manuscript was in circulation among Persian-speaking Ṣūfī Jews in the region of Punjab, where Ṣūfī connections were already present.

Fig. 5. Detail from the Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms. Heb. 28°5088, Fol. 129r.

Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

Furthermore, beside the mention of the Bahavalpur in Punjab there are numerous other poems written both in Persian and Hebrew scripts which are signed as ز ید علی شاه / از ید علی شاه / ze yad-e ʿAlī-Šāh / az yad-e ʿAlī-Šāh “[written by the] hand of ʿAlī-Šāh” (fols. 128r, 130v, 131r-132r). The scribe's name recalls again clearly the honorific titles of the masters of the Neʿmatollāhī Ṣūfī order. One of the cited poems (fol. 130v) bears a date, which is not very eligible, but eventually can be read as تاریخ ده شعبان سنه ۱۲۱۱ “the date of 10th (?) of the Šaʿbān, of the year 1211 [ah]”, corresponding to 8th February 1797. Just to give an impression of the colourful variety of the poems noticed at the back matter of the manuscript, I render one of the very last ones in Persian script (Fig. 6) which bears the aforementioned date, namely the two opening verses of a ġazal by the Persian poet of Turkish origin Molānā Badr-od-Dīn Helālī Ǧaġatāhī (ca. 874–936/1470–1529):

Fig. 6. Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms. Heb. 28°5088, Fols. 130v-131r. Courtesy of The National Library of Israel

Helālī, a faithful representative of the classical Persian poetry in Ḥāfeẓ's poetry style was well-known in Ḫorāsān and Central Asia. The mystical contents of his works, specially his mas̱navī of Šāh-o darviš (also called Šāh-o gedā) “the King and the Dervish/Beggar” made him an admired poet, even outside of the Persian-speaking boundaries.Footnote 63 Mentioning his poems here suggests not only the circulation of this manuscript, but also the likely place of its production in north eastern Iranian regions. The scribe, the same aforementioned ʿAlī-Šāh, added an interesting note to the cited poem as follows (Fig. 6):

در پشت کتاب دوستان خط بنویس، به یادگار بگذار، شاید که بدین بهانه روزی خطت نگرند، یادت آرند.

از ید علیشاه

Write a note at the back matter of the friend's books, leave them there as [your] commemoration, let's hope that by its mean, oneday s/he will look at your note and remember you. Written by the hand of ʿAlī-Šāh.

The close and friendly relationship between Iranian Muslim Ṣūfīs and their Persian speaking Ṣūfī Jews is evident.

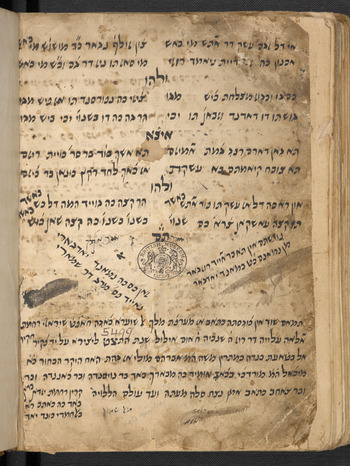

Ms Or. 4745

The last known complete Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ belongs to the rich collection of the Judeo-Persian manuscript collection of British Library.Footnote 64 Ms Or. 4745 contains 470 ġazals, alongside of other poems including the Sāqī-nāme. The 18th century manuscript is dated to 5499 of the Hebrew calendar (corresponding to 1739 ce) and is written in 120 folios (+ 1 unfoliated paper flyleaf at the end) in quires of mostly 8 leaves each, with a page size of 215 x 160 mm (written area 175 x 140 mm).Footnote 65 It has a fragile brown and black leather binding (post-1600) with Islamic end bands and spine piece from leather and tidemarks at edges and stains within the text block from liquid and usage. It has a uniform layout with 21 written lines per page in Persian semi-cursive script of the 18th century and larger square initials. The manuscript contains marginal notes and additions, as well as catchwords (rekābe) on every verso. It was purchased from its former owner S. J. A. Churchill by the British Museum on 14 February 1894. Though in general there is a lack of information regarding the production and circulation of Judeo-Persian manuscripts, Or. 4745 fortunately has an extant colophon. The complete colophon (fol. 120v, Fig. 7) reads as follows:Footnote 66

∴

תם

נושתם אין תא בראייד רוזגאר

מן נמאנם כ׳ט במאנד יאדגאר

זאן כס כה נמאנד יאדגארי

נאייד פס מרג דר שמארי

תמאם שוד אין כ׳וגִסתה כתאב אז מערפ׳ת מלךִ ﭏ שוערא כ׳אגִה חאפ׳ט׳ שיראזי רחמת

(sic) על יד פ'קיר חקיר אלאה עלייה דר רוז ה׳ שנביה ח׳ אום אילול שנת התצט ליצירא

אל בט׳אעת בנדה כמתרין משה ה׳מ׳ אברהם מולי אז גִהת האח היקר הבחור כ׳א׳

מיכאל ה׳מ׳ מורדכ'י בכ׳אגִ אומיד כה מבארך באד בר נויסנדה ובר כ׳אננדה ובר

ובר צאחב כתאב אמן נצח סלה מעתה ועד עולם הללויה.

קרין רחמת יזדאן בראן באד כה כאתב רא בﭏחמדי כונד יאד.

∴Finished!

I wrote this so when the time comes,

When I will not remain, this script will remain as commemoration;

All those, who don't bequeath any commemoration from themselves,

They won't be remembered after they death (lit. they won't be counted any more).

[Writing down of] this auspicious book of the poet laureate, the venerable Hāfeẓ of Shiraz, requiescat in pace, is finished on Thursday, the 8th of [the month of] Elul of the year 5499 of the creation of the world, by the hand of this poor fellow of scanty means, the most humble lowly servant Moshe […?] Abraham Mulī (?) for the sake of his dear brother, the young man, Mikā(e)l […?] Mordechai […?], in the hope it brings prosperity upon the scribe, and upon the reader, and upon the owner of this book, peace and eternity from now on, and forever, hallelujah.

May the one who would remember the scribe by reciting an ʾal-Ḥamd [=the Fātiḥa] be loaded with God's mercy”.

Fig. 7. Closing Page and the Colophon of the Judeo-Persian Dīvān of Ḥāfeẓ, Ms Or. 4745, fol. 120v.

Courtesy of The British Library

Not even if the colophon reveals the place of the production of this manuscript unfortunately. Though, it contains some valuable stylistic information. The colophon has a fair mixed Hebrew-Judeo-Persian vocabulary. Both names of the scribe and the owner, which manuscript was written either as a commission or as a gift are in place. A certain Moshe Avraham has copied the Dīvān for a Mikā(e)l Mordechai, who is addressed in Hebrew as האח היקר הבחור “dear brother and young man”. It is remarkable that the scribe hoped for a certain merit by coping the Dīvān in his closing prayers by uttering the wish for eternal peace and prosperity for himself as well as the owners and readers of the manuscript. Though, such closing prayers are not surprising, by having them here in Hebrew formulation, rather than the expected Judeo-Persian, it seems that the scribe saw a kind of ‘religious’ or maybe better to say ‘spiritual’ merit in fulfilling his task. He refers to himself with humble and traditional devotional formula of self-abasement as פקיר חקיר אל בט׳אעת בנדה כמתרין “the poor and insignificant lowly servant” (faqīr ḥaqīr al-bażāʿat bande-ye kamtarin), which denotes a certain commitment to the general Ṣūfī milieu. Using the very last formula of remembering the scribe by reciting a ʾal-Ḥamd (referring to the first sūra of the Quran, al-Fātīḥa), traditionally recited in Muslim funeral services and by each recalling the name of the belated ones, signifies a deep acculturation of Iranian Jewry into the Islamicate Iranian environment and most specifically into its scribal traditions.

Conclusion

One more aspect that could not be treated here is certainly the relation between Jewish Kabbala and mysticism to Iranian Muslim Ṣūfism. It is fair to suppose that the preoccupation with Jewish kabbalistic issues was a fact that cannot be neglected by talking about the Iranian and Persian-speaking Jewish tendencies towards the influence of Persian Ṣūfī literature. The lack of any systematic study of the manuscripts regarding this issue is a serious desideratum, which still must be undertaken. In the lack of any certain knowledge regarding either kabbalistic groups arose within the Iranian Jewish community or less conceivable influence by the European Hassidic streams, though, it can in so far be observed, that such a relation between the two mentioned metaphysical movements could indirectly be promoted by the popularity of the aggadic and halakhic Midrašim among Iranian Jewry and within Judeo-Persian literature.Footnote 67 Persian-speaking Jews were able to adopt the dominant Ṣūfī symbolical language and terminology alongside its mystical elements in the expression of their own, Hebrew Bible-derived, theology and philosophy.