INTRODUCTION

Background

Medical education is a sizeable field that encompasses many research paradigms. One of the exciting areas of growth in the past 30 years has been the surge of work rooted in qualitative methods. Qualitative approaches stem from social science research practices. Rather than quantifying, predicting, or modeling outcomes, they aim to create a deep understanding of a situation or phenomenon.Reference Bergman, de Feijter and Frambach 1 - Reference Tavakol and Sandars 3

These methods have been largely underused in emergency medicine (EM) medical education circles, but they have the opportunity of making a great impact on educational practice. Qualitative studies delve into the richness of complex phenomena, seeking to answer the “whys” and “hows.” These pursuits contrast with quantitative studies, which aim to answer focused questions (“Does this intervention work?”, “How much does this change that?”).Reference McKinley 4 In the past decade, there has been a growing interest in applying the qualitative paradigms to answer questions in the larger field of medical education,Reference Sullivan and Sargeant 5 - Reference Teherani, Martimianakis and Stenfors-Hayes 7 but there has been less uptake regarding qualitative methods in education papers within our specialty.

Despite this, a burgeoning respect for the use of qualitative approaches has developed in EM. In 2007, the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) consensus conference on knowledge translation affirmed that qualitative research has an important role for advancing the cause of translating knowledge to the bedside.Reference Compton, Lang and Richardson 8 Although this statement emerged from a broader context than EM education, it demonstrated an appreciation of the role of qualitative work in understanding the contextual nuances of implementing educational programs and inciting behavioural change. Since 2013, a group within the Academic Emergency Medicine journal has highlighted qualitative studies in their annual review of EM education papers.Reference Farrell, Kuhn and Coates 9 , Reference Yarris, Juve and Coates 10

Many qualitative methods draw from the social sciences, each method bringing with it the perspective of its originating field. Table 1 describes some of the commonly applied qualitative methods in education research and includes exemplar papers that fit within each paradigm.

Table 1 Key features of various qualitative methods

Qualitative research often receives critique, especially from reviewers unfamiliar with these methods, regarding perceptions of excessive bias or anecdote, vague or heterogeneous methodology, and absence of external validity or rigour.Reference Ziebland and McPherson 17 Fortunately, useful guides exist to help readers and reviewers better understand qualitative work such as the User’s Guide series from The Journal of the American Medical Association.Reference Giacomini and Cook 18 , Reference Giacomini and Cook 19 As these guides outline, qualitative research has its own set of rules that govern rigour, and threats to validity that can be addressed and minimized with thoughtful study design and execution.

This paper presents the results of a scoping review that aims to identify literature-based resources that EM educators may use to design, implement, and author qualitative research studies. Our literature search focused on a key primary question: what are the quality markers for qualitative educational research as described in the literature? We also explored the literature from our search to answer the following three secondary questions: 1) How frequently are qualitative papers published in EM journals? 2) Which journals regularly publish qualitative educational papers? 3) What are commonly used quality checklists for qualitative educational research?

METHODS

Literature search to identify relevant studies

We performed a scoping review using the approach described by Arskey and O’Malley.Reference Arskey and O’Malley 20 We conducted an initial search using the MEDLINE database from the National Library of Medicine as well as the ERIC database in December 2015. Our search was limited to human and English language papers using “and/or” combinations of variations of the following keywords: qualitative, emergency medicine, qualitative methods, and medical education. An adjunctive search was undertaken via Google Scholar. Google Scholar has been previously noted in the literature as an alternative search method that can replace the use of other databases for review papers.Reference Gehanno, Rollin and Darmoni 21 In this instance, we used it to supplement our other database searches.Reference Paterson, Thoma and Milne 22 , Reference Chan, Wallner and Swoboda 23 The keywords medical education, emergency medicine, and qualitative were used. We did not specify a time period for publications and accessed all literature available in the MEDLINE and ERIC databases from their beginning date. A master list was created of all articles resulting from the three searches, duplicates were excluded, and a manual search of the references of final papers was conducted to identify additional papers to add to the master list.

Selection of articles for the scoping analysis

Two investigators (TMC, DKT) performed the literature search and reviewed titles for relevancy. For the scoping analysis, we included all papers that provided guidance to authors wishing to conduct, report, or write qualitative studies or educational scholarship. We did not limit the inclusion of articles to EM literature, and instead looked more broadly into the general medical and medical education literature. We excluded papers that merely used qualitative methods. These excluded papers were kept and used for the frequency analysis, which is mentioned later in our methods. To ensure interrater consistency, the first 100 titles obtained from the MEDLINE search were reviewed together to determine consensus on which types of titles were to be included or excluded.

Charting and analysis of the quality markers

Our primary aim was to develop a literature-based set of quality markers for qualitative research, which we defined as items that were written as advice to authors of qualitative research that were not already within known qualitative scoring systems. To identify candidate quality markers, a single investigator (TMC) read the full-text articles remaining from the literature search after inclusion criteria were applied. Quality markers mentioned in the text, diagrams, figures, or tables were extracted into a master list.Reference Sebok 24 These quality markers were combined into one single master list, and then a close analysis was performed by a single investigator (TMC) to group and reduce this list in the manner described by Arskey and O’Malley into its final form.Reference Arskey and O’Malley 20 To enhance the rigour of this analysis, two investigators (DKT, JM) surveyed the analysis audit trail (i.e., the analysis documents) after reviewing the 11 full-text articles.

Qualitative publishing frequency and journal identification

To identify journals that publish qualitative research relevant to EM education, we determined the overlap of qualitative medical education research papers and qualitative research in EM. This frequency analysis was done with medical education papers using qualitative methods that were found in our initial literature search, but which were excluded from the scoping analysis. After merging the results of the three database searches and excluding duplicates, the citations were manually sorted using the Mendeley reference software into mutually inclusive categories of “qualitative research,” “medical education,” “emergency medicine,” or combinations of these two groupings (i.e., “qualitative research and emergency medicine” or “medical education and emergency medicine”). When the article title resulted in ambiguous characterization, the abstract or full-text was reviewed. We then generated a list of journals that had published at least one qualitative research articles relevant to EM medical education. From this list, we also produced a subset of journals with at least two qualifying publications.

Quality checklist identification

The manuscripts reviewed in the full-text phase were read in total by two authors (TMC, JM), and papers with relevant checklists were extracted.

RESULTS

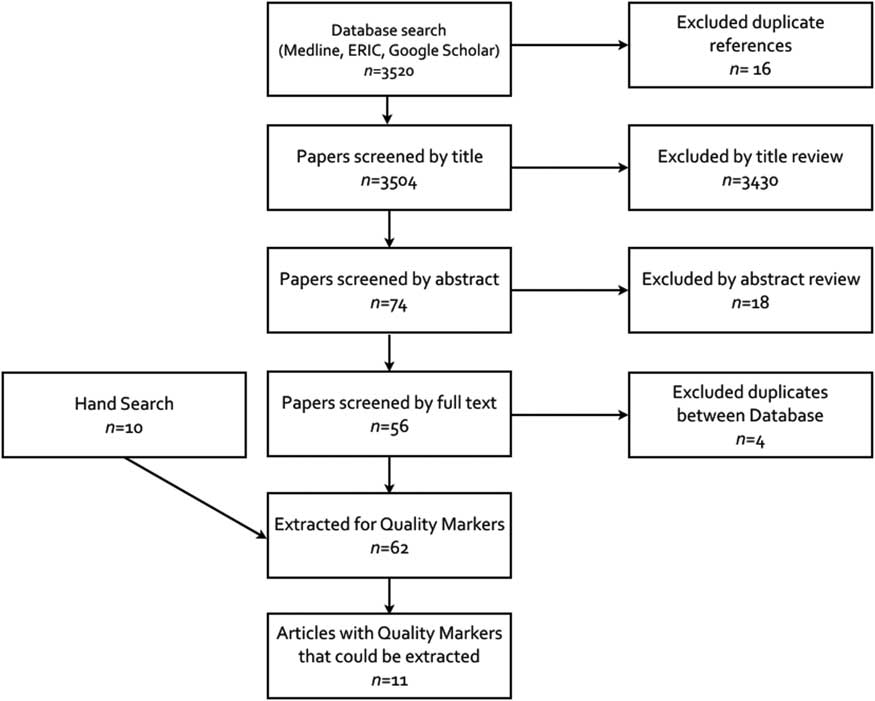

Citations totalling 1,337 were obtained from our search strategy. These papers were reviewed for duplication and then subjected to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Figure 1 depicts how papers were removed at various stages to arrive at the final set of full-text papers used for the scoping analysis (n=11).

Figure 1 Flow diagram for literature review.

Quality markers for qualitative studies

We reviewed 62 papers in full-text form for quality markers. Of these, 11 papers had specific items that could be extracted for the close analysis. Appendix A lists the 11 papers. Table 2 contains the results of our thematic analysis of quality markers in qualitative research, based on the close analysis of relevant papers from our literature review.

Table 2 Markers of quality in qualitative education research studies

Quantifying the qualitative publishing rates

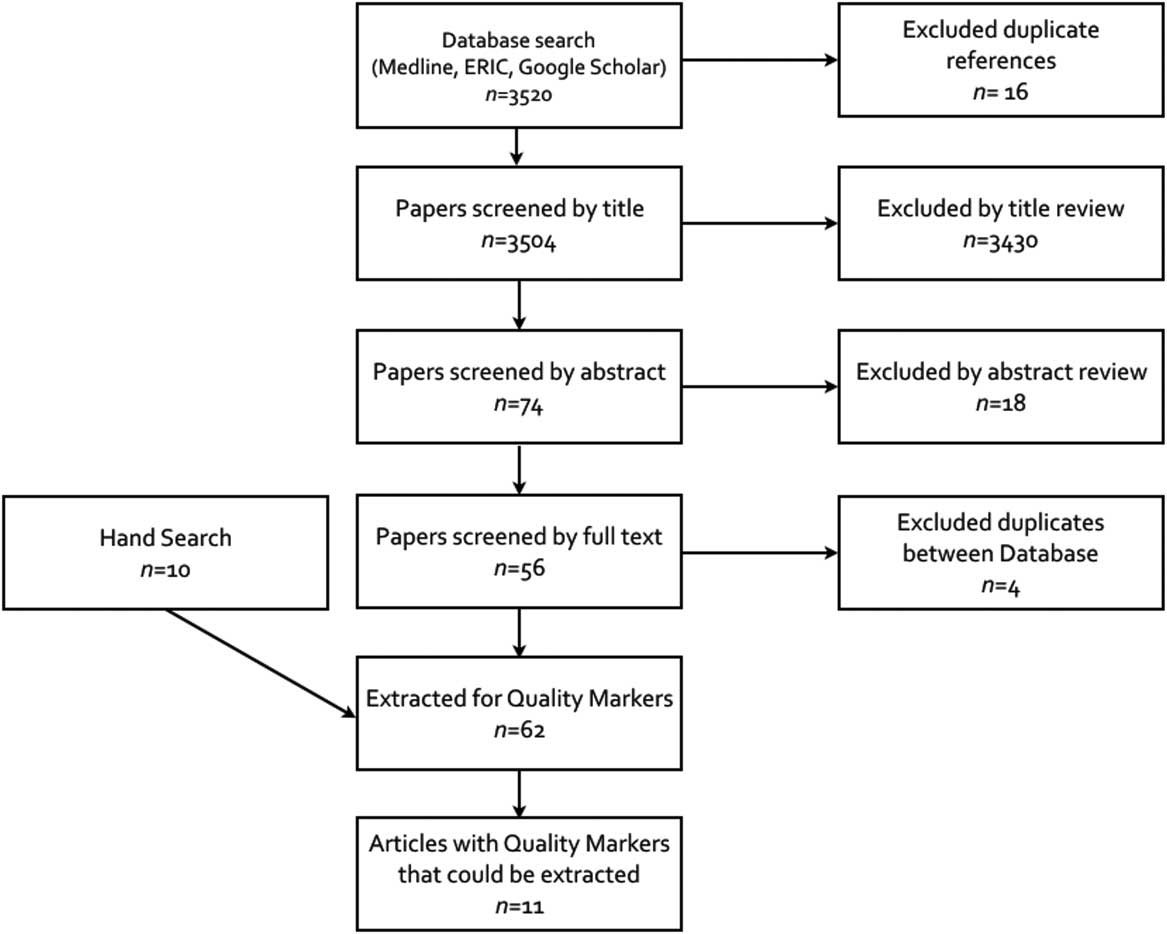

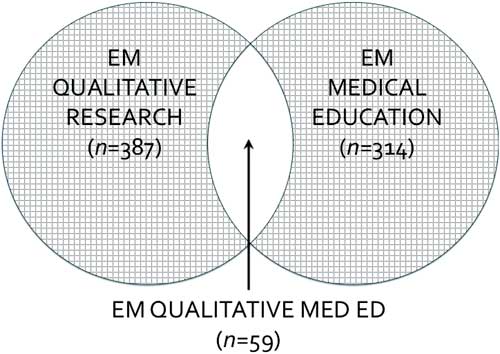

Our literature search revealed a separate set of 387 citations of EM qualitative research papers and 314 of EM medical education papers; 59 citations overlapped between these two categories, which represent qualitative education research relevant to EM (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Number of emergency medicine, qualitative and medical education papers in our literature search.

Checklists for quality

Our search identified five papers that had developed and reported checklists or scoring metrics useful for evaluating qualitative research (Table 3). The fifth paper by Sullivan et al. reported features useful for determining quality and value of both qualitative and quantitative research. These checklists would all be useful for consultation when designing a qualitative study, writing and editing manuscripts, performing editorial review of manuscripts, and performing critical appraisal of a qualitative paper.

Table 3 Checklists to evaluate qualitative work

We found 33 journals that publish EM qualitative research in medical education (Appendix B). Of these, 9 journals had at least two qualifying papers, as listed in Table 4.

Table 4 List of journals with at least two citations of qualitative research in emergency medicine medical education, listed in alphabetical order

DISCUSSION

Qualitative methods have the potential to provide us with new insight and clarity into the educational problems and dilemmas that we face within our specialty. As illustrated in Table 1, there are wide ranges of research methods that can be used to answer questions within the field of medical education. Furthermore, as evidenced by Table 4 and Appendix B, there are an increasing number of medical journals amenable to publishing rigorous qualitative work in EM and medical education. Figure 2 depicts that approximately 18.9% (59/314) of the EM education papers in our literature search were qualitative in nature. Similarly, we found that a slightly smaller proportion of EM qualitative papers (15.2% [59/397]) were educational papers. Taken together, our findings suggest that, despite a growing interest, only a minority of studies use qualitative methods. Given that many educational problems involve emerging theory or little understood phenomenon, we propose that qualitative methods are underused in EM education.

Interestingly, our thematic analysis of the 11 papers with advice and tips for writing qualitative methods yielded disparate items from those addressed in the checklists described in Table 3. Some of the items that we found were broader in their scope (i.e., more general guidance) around important aspects to consider when writing a qualitative paper. As such, we feel that the list generated by our present scoping review may help augment the advice presented by the previous literature, because it aggregates the wisdom reported in papers that may not have been used to inform the creation of previous checklists (e.g., the SRQR).Reference O’Brien, Harris and Beckman 32

There are, however, a number of challenges and barriers to using qualitative research.Reference Ziebland and McPherson 17 For instance, researchers using these techniques must be tolerant of ambiguity and be comfortable in presenting non-numerical data. Also, unlike quantitative studies, researchers must be intimately involved in the generation and interpretation of data.Reference Sargeant 6 Swaths of work cannot simply be outsourced to a junior collaborator or a hired statistician. Finally, regardless of the type of medical education scholarship, novice educators may find it difficult to get their research published, whether they are engaged in qualitative methods or not.Reference Norman 33

This scoping review and adjunctive analyses provide resources that may be useful to educators in designing, implementing, and writing up qualitative research. Attention to quality indicators and awareness of available checklists and publication venues may help educators overcome common obstacles to publication, and increase interest and engagement in qualitative research.

LIMITATIONS

This paper provides a literature-informed review of existing guides for conducting and authoring qualitative research in EM. Although it cannot replace formal methodological training and mentoring, it may serve as a complementary resource that can scaffold early career and new qualitative scientists when writing within medical education. Although efforts were made to systematically search the literature, it is possible that relevant publications could have been missed, especially because our search was restricted to the English-language only. In addition, inclusion processes and thematic analyses do involve researcher involvement in the data, and it is possible that saturation was not reached, either of the relevant papers, or of the quality markers.

CONCLUSIONS

There are many papers to guide early education researchers towards reporting and conducting high quality qualitative research. We have reported 39 quality markers that should be considered when authoring qualitative medical education studies, which we have grouped into 10 key categories. Additionally, we present five previously published quality checklists, which will assist authors in preparing qualitative manuscripts for publication. Our paper may serve as a primer for early career educators who aim to enhance the rigour of their qualitative educational research.

Competing interests: None declared.