Despite the ever-expanding body of theory that reaches almost every corner of film music, consideration of music in radio drama is patchy and threadbare. Since the early days of radio, work has been undertaken about various aspects of radio’s sound as music (Rudolf Arnheim’s 1936 Radio: An Art of Sound, for example, brought out the need for radio dramas to be alive to the ‘musical elements of speech and all sounds’), but little attention has been paid to the music within popular radio drama.Footnote 1 Neil Verma’s Theater of the Mind comes perhaps closest, with its virtuosic exploration of the stylistic changes in ‘old-time’ radio drama – the 1930s thematization of psychological plots, the 1940s plots about information transmission, and so on.Footnote 2 But while Verma notes the significance of early composers for radio drama such as Bernard Herrmann, no framework emerges for discussing musical contributions which so often prove to be a major force for delivering radio drama. The recent collection of essays Music and the Broadcast Experience contains but few references to this topic.Footnote 3 Rika Asai’s essay bases its whole discourse on Erving Goffman’s concept of ‘framing’ and the radio-drama frame which ‘focuses solely on the role of music and sound in representing “realism” in radio drama’.Footnote 4 But music’s role in ‘framing’ dissipates as we move further from Goffman, whose theories draw our attention to factors specific to the musico-radio dramatic frame. Goffman describes, for example, how the music forms ‘bridges’:

Music does not fit into a scene but fits between scenes, connecting one whole episode to another – part of the punctuation symbolism for managing material in this frame – and therefore at an extremely different level of application than music within a context.Footnote 5

Asai applies Goffman’s theory of framing to explore Benny Goodman’s on-air party Let’s Dance, and the topic of music and radio drama is set aside.

The irony of the under-exploration of music’s role in radio drama is not a small one, in that without a visual image to divert us, music generally operates closer to the foreground of our attention than it does in audiovisual media, connecting the various aspects of sound by means of what Arnheim calls an ‘acoustic bridge’:

By the disappearance of the visual, an acoustic bridge arises between all sounds: voices, whether connected with a stage scene or not, are now of the same flesh as recitations, discussions, song and music.Footnote 6

Some well-documented, highly novel sound explorations took place in the early experimental history of radio drama, particularly in avant-garde German radio, where the Hörspiel moved further away from the theatre that had been at the heart of the English radio play.Footnote 7 Whereas the Hörspiel had taken early inspiration from Anglo-American radio plays such as Richard Hughes’s A Comedy of Danger (1924), by the 1970s, Mauricio Kagel was showing us that Neues Hörspiel had its roots in the Weimar avant-garde.Footnote 8 Even in 1928, Walter Ruttmann created his experimental audio-only ‘film’ Weekend, commissioned by Berlin Funkstunde, which evoked expressionist soundscapes through montage techniques.Footnote 9 In Britain, under the control of the BBC, radio drama served as a modernist vehicle for artists such as Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (Sintesti, 1933) and Ezra Pound (the radio opera Cavalcanti, 1931). Debra Rae Cohen singles out Lance Sieveking, head of the BBC’s Research Section, as the perpetrator of much ‘radiogenic experiment’, creating impressionist-inspired dramas with techniques such as montage and fade being transported from cinema.Footnote 10 This tradition fuelled the musical experimentation of the 1950s, not least in the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s cutting-edge compositions for radio shows. More recent BBC experiments in radio drama have included The Foundation Trilogy (by David Cain, 1973) and Andrew Sachs’s The Revenge (1978), a mainstream continuation of this experimental tradition consisting only of sound effects and non-verbal utterances of the central character (Sachs himself). Such experiments were intensely musical, but music also plays a major role, though perhaps a less overtly ‘modernist’ one, in the more traditional genre of the English radio play that continued to develop in parallel.

In 1949, Boris Kremenliev was among the first to offer a practical account of composing for radio drama, though he perhaps began on the wrong foot by relegating music to the ‘background’ in his title: ‘Background Music for Radio Drama’.Footnote 11 In radio drama, when music is heard between voices and sound effects, it is often the only thing on which the audience can focus, and thus appears in the foreground. Without competing visual stimuli, it can be easier for listeners to be actively engaged with music, since there is space in the imagination for them to ruminate over its significance.Footnote 12 Kremenliev does offer a broader taxonomy of functions for music in radio drama: ‘The music used in the present unseen drama falls into one of four categories: signature, curtain, bridge, and background.’Footnote 13 The signature is the music that opens and closes the show, but the other three categories are more embedded in the drama itself:

A curtain indicates the end of an act or a scene which the producers think (perhaps justifiably) might otherwise lack finality. A bridge conveys the impression of transition in time or surroundings and is seldom more than ten seconds long. Often a bridge must contain two ideas, commenting on the scene completed and foreshadowing the one to come. Background music per se is music that actually backs up speech or action and contributes to the prevailing mood of the scene.Footnote 14

Because we cannot see what is happening in the story, the directors, dramatists and musical directors must orientate us and escort our imaginations. The field of stimulus is in one sense shallower than in film, but in another sense much deeper because the listener’s imagination must fill the gap – hence the title of Verma’s book referred to above. Verma notes that Paul Fussell called the 1940s a ‘special moment in the history of human sensibility’ in which radio fired the ‘creative imagination’, which in turn substituted for visuals.Footnote 15 He also notes the extent to which by the 1930s radio drama had ‘begun to evolve from an expressive activity driven by narration to one driven by scene’.Footnote 16 Andrew Crisell states that, ‘Because radio drama shows less and involves the imagination more, it can “stage” a whole range of situations which are quite beyond the scope of conventional drama.’Footnote 17 And as Kremenliev avers,

Radio background music, like music in opera, motion pictures, musical comedy, ballet, and television, serves essentially to create atmosphere and heighten emotion. It keeps the story moving by giving it color and by holding the attention of the listener. And it has an added, special function peculiar to the medium because it must attempt, together with the narrator and sound effects, to compensate for the missing visual image.Footnote 18

Kremenliev’s comparison with opera, movies and so on seems natural enough, but my aim is to shine a light on some of radio’s specific characteristics. The theoretical terms from audiovisual studies will prove particularly useful as starting points, but such tools need to be adapted, and consideration needs to be given to the particularities of radio.

In order to tease out the musical possibilities that radio drama offers, I have chosen the long-running BBC Radio dramatizations of the complete Sherlock Holmes canon of 60 stories, a project that grew out of a series of adaptations by the head writer Bert Coules.Footnote 19 The series ran from 1989 to 1998, starring Clive Merrison as Sherlock Holmes and Michael Williams as Dr John Watson. Music is prominent throughout the series, offering sometimes crucial layers of meaning. One producer-director, Enyd Williams, reflected at the end of the project:

I was particularly pleased with the Valley of Fear; its atmosphere, its drama, and especially the music. Our musical director Michael Haslam worked wonders with his piano and violin arrangements, and it was a real pleasure to watch him as he played the piano in the action, capturing the different characters of the various players. He was just as much an actor as the rest of the cast.Footnote 20

A cursory comparison with other dramas such as the BBC’s Agatha Christie collection shows that the Holmes collection integrates music with greater intricacy. The Christie shows use different signature music for each dramatization, but have scant diegetic music and very few bridges, curtains and background pieces. The Holmes series also compares favourably with some radio dramas that should call for greater musical sophistication, such as the 2010 adaptation by Lavinia Greenlaw of Hermann Hesse’s The Glass Bead Game – a dramatization of a novel that had music at its heart. The adaptation fails to live up to our deepest imagined ideas about the complexity of the profound ‘game’ (which synthesizes academic disciplines), and the triviality of the music played – such as Pachelbel’s Canon – robs us of a certain amount of awe. There were at least four musicians working in the production team of Sherlock Holmes at different times – the late violinist Leonard Friedman, the violinist Alexander Bălănescu, the pianist Michael Haslam, who took over from Friedman as musical director mid-way through, and the violinist Richard Friedman. The dramas generally use precomposed music from the classical repertoire, though Leonard Friedman would often improvise passages on the violin, and Haslam would make piano arrangements.Footnote 21 In avoiding common radio clichés, such as the ‘stings’ so often trivialized in the Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce radio shows from the 1940s, where an organist would hit a diminished-seventh chord to mark Holmes’s pronouncements as portentous, the BBC Sherlock Holmes series achieved a level of sophistication that pushes some of the boundaries of what can be achieved in radio dramaturgy. Experimenting with different narrative strategies over a nine-year period, and offering a staggering range of musical effects, they covered around 48 hours of radio time. The series therefore serves our reflection well and will raise fundamental questions about music in radio drama, so neglected in academic study.

Using these 60 shows as my case study, then, in the present article I will first explore and unpack prevalent notions of diegesis, some of which will prove useful,Footnote 22 but will also establish Pierre Schaeffer’s term ‘acousmatic’ as particularly pertinent,Footnote 23 considering how its accompanying concept of ‘visualization’ can work even without vision. Ultimately, this will lead me to question the ubiquitous violin music in the series and explore the different narrative positions that it represents, considering how it frames the dramas. I then examine ways in which music creates a fantasy space between two representations of the same dialogue, before unpicking the ways in which music’s presence marks an absence – a fundamental ‘lack’ among the characters. Finally, I will study the ways in which precomposed musical intertextual allusions create what I call a ‘paradiegetic’ space. While many of the techniques explored here can (and do) work in television or film, I shall keep an eye (or rather, an ear) on (a) how they work differently in radio narratives, and (b) how some are more prevalent or more intense in radio, usually as an attempt to fuel our imaginations in the absence of visual cues. While most of the ‘tricks’ discussed here can, and do, find clear analogies in film, some of them are particularly germane to radio and work differently in this medium, where the imagination provides the images.

Radio diegesis and the acousmatic frame

One of the main features of music in radio drama is that the distinction between the so-called ‘diegetic’ layer (music that the characters can hear) and the ‘non-diegetic’ (that which they cannot) is harder to determine than it is on screen, because we cannot see the source of the music. It thus takes greater subtlety of direction – and often a longer timeframe – to orientate us within the soundscape. The terms diegetic and non-diegetic have been weighed up in recent years, and some of the refinements and extensions may prove useful to us. Several commentators discuss the liminal boundary in film music between these terms – what Robynn Stilwell calls ‘the fantastical gap’,Footnote 24 or what Henry Taylor and Aaron Hunter call the ‘trans-diegetic’ movement.Footnote 25 Daniel Yacavone refers to a ‘diegetic world’ that characters inhabit versus a ‘film world’ that denotes the overall film system,Footnote 26 chiming with Ben Winters’s return to Daniel Frampton’s ‘Filmind’.Footnote 27 Anahid Kassabian argues that with the advent of video-game music and music for phone apps, new media has taken us to ‘the end of diegesis as we know it’.Footnote 28 Even in film music, Winters objects that, ‘Branding music with the label “non-diegetic” threatens to separate it from the space of the narrative, denying it an active role in shaping the course of onscreen events, and unduly restricting our readings of film.’Footnote 29 Reserving ‘diegetic’ for music that the characters actually hear or produce, Winters adopts other terms to delineate the different levels of narration. Thus ‘metadiegetic’ (a term generally used by Claudia Gorbman to describe music being heard in a character’s mind),Footnote 30 for Winters, means discourse that occurs during secondary narration by a character. Meanwhile, ‘extra-diegetic’ – which Gorbman uses to mean ‘non-diegetic’Footnote 31 – occurs at a level below the diegesis.Footnote 32

These concepts will prove useful in some corners of the present project, even without vision, but as a starting point for a study of radio, a more apt notion is Michel Chion’s one of the ‘acousmatic’, a term that was first introduced to us through Schaeffer’s musique concrète and has become common in audiovisual parlance. ‘Acousmatic’, specifies an old dictionary, ‘is said of a sound that is heard without its cause or source being seen.’Footnote 33 This is the zone in which radio, even more than film, resides, but because everything in radio is acousmatic, the term’s relationship to ‘visualization’ needs to be rethought for this context. As Schaeffer used the term in relation to his musique concrète, it attempted to provide a phenomenologically ‘reduced’ form of listening, following the Husserlian epoché, where listeners were invited to listen to sound objects without associating them with their means of production (what Schaeffer calls ‘anecdotal’ listening).Footnote 34 The term ‘acousmatic’ was associated with Pythagorean sects who listened to their master’s voice from behind a screen;Footnote 35 this magical voice was called the acousmêtre, a concept we shall unpack in due course.Footnote 36 Chion says of radio:

It should be obvious that the radio is acousmatic by nature. People speaking on the radio are acousmêtres in that there’s no possibility of seeing them; this is the essential difference between them and the filmic acousmêtre. In radio one cannot play with showing, partially showing and not showing.Footnote 37

‘Visualization’: showing/not showing in radio shows

Chion possibly overlooks the subtleties of the work of radio dramatists, who skilfully create layers of sound and action that ‘show’ us things in our imaginations – by making the source of sound clear to us – even without visuals. When we listen without images, for Chion, sound is ‘acousmatized’; when the source of the sound becomes clear, it is ‘de-acousmatized’, ‘demythologized’ or ‘visualized’. While ‘visualized’ is to be taken literally in film, we might extend the term ‘visualization’ to radio, referring to a mental image of a revealed sound source.Footnote 38 Chion speaks of ‘instantaneous perceptual triage’ as a moment when we form immediate assumptions about how the music fits into the scene, concluding that, ‘It is the image that governs this triage not the nature of the recorded elements themselves.’Footnote 39 This is not the case in radio, as there is no visual image, but the elements of sound can produce a mental image of diegetic insideness or outsideness. Indeed, one of the primary tasks of music in the ‘blind’ medium is to help us to visualize where we lack visual clues to set the scene. As Verma notes:

To create plays that evoked spatial and temporal structures in the mind, 1930s dramatists required a set of sonorous marks that could inform auditors where they ‘were’ and signify movement from one scene to the next. Perhaps the most expedient of these devices was music, a few bars of which could, in the words of one CBS executive, ‘take the place of scenery, lighting and costumes’ or, as an NBC writer put it, ‘span continents or centuries in a few seconds … like a magic carpet’. A hint of stride piano evokes Harlem in the 1910s; ‘La Marseillaise’ suggests France – in this way dramatists neatly incorporated into the play a network of preexisting associations and understandings among listeners in an audience, simplifying the task of representation by deploying fertile seeds of information.Footnote 40

In the Holmes radio drama collection, we find many instances in which musical directors manufacture qualities in the music that make it realistic to the diegetic world (that is, believable as music that the characters can hear) through manipulations of volume, ambience, resonance, panning and reverb, and even musical ‘quality’. The same occurs in film, of course, though radio perhaps relies more heavily on the ‘grain’ of the performance without a visual cue to gauge the source of sound.Footnote 41 In ‘The Crooked Man’ we are located squarely in a Victorian drinking bar, because the piano that plays at the beginning is out of tune and we hear conversational noise, with drunk singers providing the musical entertainment of which the characters are part. When we hear in ‘The Mazarin Stone’ the crackly sound of Hans Sachs’s singing in Act 2 of Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg or hear in ‘His Last Bow’ Wagner’s Siegfried Idyll, we know that we are in a drawing room, and that we are listening with the characters to new gramophone technology. At the beginning of ‘The Resident Patient’, when we hear the distant chimes of Big Ben recorded low in the audio mixFootnote 42 and a barrel organ with moving stereo panning, we know that we are strolling through a London park.Footnote 43 Further, when Holmes makes deductions about Watson’s train of thought which involve his perception of this barrel organ, the sound field is fully ‘visualized’ or ‘demythologized’. Thus, in radio, one can ‘show’ the location of music – and our subjective point of view (or as Verma calls it, our ‘audio position’)Footnote 44 – and this often involves making the music as real as possible (which often means flawed).Footnote 45 This all requires us to be what Roland Barthes would call ‘alert’ listeners and to make judgments about how likely the sound is to be what Chion calls ‘pit music’.Footnote 46 We hear music that could be pit music, but because of its appropriateness to the physical rather than the emotional situation, we may more readily accept it as ‘visualized’ in the diegetic world. Such is the case with the Strauss waltz that accompanies the first meeting of two lovers in ‘A Case of Identity’, which places us squarely in a Victorian dance hall even before Mr Angel invites Miss Sutherland to dance. In ‘The Disappearance of Lady Frances Carfax’, a similarly visualized string quartet plays a Swiss ländler in a hotel. Techniques that convey the ‘reality’ of the musical production – that bear the trace or grain of production – can all serve to ‘visualize’ the sound sources and, as we shall explore, can be used to play subtle games.

Often the ‘visualized’ nature of the music is confirmed by a simple ducking technique whereby the sound reduces volume as the characters begin to act, the volume being proportional to the characters’ engagement with the music: if the characters are paying attention to the music, it is louder; if it goes unnoticed, it is quieter. Chion discusses this ‘cocktail party effect’ where an auditor masks a general hubbub to zoom into a specific conversation,Footnote 47 and these ducking effects are common in radio drama.Footnote 48 The cocktail party technique is used to particularly good effect in the opening of ‘The Veiled Lodger’, when the overblown circus music fixes us in the diegetic circus ring (our unconscious triage mechanism might ask: ‘Why else would a Sherlock Holmes drama start with circus music?’) and then immediately ducks to become a distant sound as we focus on the characters in the wings who are preparing to go onstage. This creates a rather literal instance of Chion’s ‘in the wings effect’, where a diegetic sound lingers as we leave a scene.Footnote 49 When the tragic heroine of the tale, Mrs Ronder, takes to the stage, the sound pans to fill the audio spectrum with herself in the centre through an agreement of our point of view with hers. These instances of ‘visualized’ background music, which clarify our auditory point of view, tend to work quite intuitively and effectively, providing the conceptual backdrop for much invention in playing with the presence or absence of music within the dramatic frame of the sound field.

A director of radio drama certainly can ‘play with showing, partially showing and not showing’, pace Chion, even where everything is invisible. The Wizard of Oz’s booming voice is just as ‘visualized’ as a man behind a curtain in Frank Baum’s novel (1900) as it is in the MGM film (1939). This is in fact the coup de théâtre of one of the Holmes stories as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle conceived it. In ‘The Mazarin Stone’, Holmes utilizes this very trick by pretending, with the aid of a gramophone, to play the violin to his students in an adjacent room, all the while in fact hiding behind a curtain. The villains, hearing Holmes’s performance of the Barcarolle from Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann, thus believe him to be absent, and audibly reveal the location of a stolen jewel. Holmes then appears, putting us listeners in the same duped position as the villains, though at different narrative levels. All are surprised when Holmes steps forward, revealing himself not as the source of sound but as the source of non-sound, showing that the music behind the wall was not his own. The door is opened, and we hear the crackle of the gramophone. The music is ‘visualized’ by Holmes, and although he was not the direct source, he was nonetheless the master of the acousmatic zone.

More often, however, the reverse happens, where what we imagine to be acousmatic – outside the frame – turns out to be inside; it is ‘visualized’ or demythologized. Twice in the series, violin excerpts that so often serve as acousmatic ‘bridge’ passages suddenly turn out to be part of the diegetic world, moving from the level of narrator to the level of narrated. In the first of the short stories, ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, the acousmatic violinist suddenly makes a mistake in the Sarabande from Bach’s Partita no. 1 in B minor, and we realize that Holmes is playing within the diegetic space; he has been distracted by Watson’s entrance. In a parallel moment in ‘The Final Problem’ (the story in which Holmes famously ‘dies’), Moriarty interrupts Holmes playing Paganini’s Caprice no. 4 in C minor, and the excerpt we might have assumed to be one of many bridges or ‘flourishes’ (as they are often referred to in the scripts) is included in the diegetic frame. We can then immediately reflect on the significance of the music – a piece for solo violin but with a two-part canon whose polyphonic voices represent the intertwining destinies of the two masterminds, Holmes and Moriarty. When the same piece returns in ‘The Missing Three-Quarter’, Holmes musically (as well as verbally) compares his antagonist, Dr Leslie Armstrong, to Moriarty. These devices concern our sliding perception of agency, not necessarily shifting our audio position from outside to inside the diegesis (though this is certainly one effect) but allowing us to be in both at the same time. The violin is being played by Holmes; therefore Holmes possesses narrative agency. This runs contrary to the tradition, continued in the dramatizations, that Watson – as controller of the diegetic realm, where Holmes is the (mimetic) actor – is Holmes’s ‘Boswell’, narrating the stories years after they occurred.

This may remind us of the film Without a Clue (1988), in which ‘Holmes’ (actually an out-of-work actor, played by Michael Caine) is the slapstick puppet for the ‘real’ detective, Dr Watson (Ben Kingsley), who is both narrator and ‘real’ subject of narration. The film plays on a certain trait of humorous ‘one-upmanship’ between Holmes and Watson in the stories, perhaps most recently featured in a sketch by Mitchell and Webb in which two actors have to change roles from scene to scene in order to solve the argument about who gets to play Holmes. In a perhaps less light-hearted version of this sport, what we find in these dramas, as we shall now explore, is a situation in which Holmes’s musical activity pushes him into the same storytelling space that Watson occupies, staging a narrative tug of war. Even in the dialogue of Coules’s scripts, the pair reach the outer layers of the narrative frame, sometimes even discussing their own portrayal in early twentieth-century popular culture. For one thing, the complaints (present in the books) from Holmes about Watson’s over-romanticization of their adventures in the Strand Magazine, are developed into a discussion about the infamous William Gillette stage portrayal of Holmes in 1899.Footnote 50 These twists from Coules form an obvious way of engaging Holmes in the narrative strategy at several levels of narration above the story itself. The musical contribution to these narrative games, however, involves more subtlety and warrants still deeper investigation.

Holmes’s violin and narrative agency

Many of the musical excerpts trade on Holmes as a violin player, creating profound effects on the levels of diegesis within the musical acousmatic frame. It is established at the beginning of the canon that Holmes is a violinist. In an early scene of ‘A Study in Scarlet’, Coules has Holmes playing to Watson the Gavotte from Bach’s Partita no. 2 in E major, switching whimsically to Gilbert and Sullivan’s ‘I’m Called Little Buttercup’ and, later, Wagner’s ‘Song to the Evening Star’ from Tannhäuser. Furthermore, in this crucial early scene, Holmes presents himself as musical narrator of the drama. A famous moment in Holmes and Watson’s relationship is when Holmes finds Watson’s list of Holmes’s limitations, reading it back to him with great relish (‘Astronomy: Nil; Politics: feeble’, and so on). Improvising a cadential flourish on the violin, Holmes announces himself – ‘Sherlock Holmes …’ – before hitting a dissonant ‘bum note’ in the low register and continuing, ‘… his limits’. He then reads out Watson’s list, much to the latter’s chagrin. From here onwards the violin music is associated with Holmes, and it could always be him playing, even in the violin passages that acousmatically suture some of the scenes together. The status of the violin in the narrative frame is forever questionable, and we are kept in a kind of suspended diegesis, never entirely sure where exactly Holmes is, and at which level of narration he operates. This may remind us of Goffman’s analysis of how the same piece of music can operate on different narrative levels – ‘the same piece of music is heard differently or defined differently’ – and can perform a radically different ‘frame function’.Footnote 51 In fact, through Holmes’s violin music, he is capable of being in two places at once through different diegetic levels; he becomes the grand acousmêtre of the dramas. Chion defined the acousmêtre thus:

The acousmêtre is this acousmatic character whose relationship to the screen involves a specific kind of ambiguity and oscillation […] We may define it as neither inside nor outside the image. It is not inside, because the image of the voice’s source – the body, the mouth – is not included. Nor is it outside, since it is not clearly positioned offscreen in an imaginary ‘wing’, like a master of ceremonies or a witness, and it is implicated in the action, constantly about to be part of it. This is why voices of clearly detached narrators are not acousmêtres. Footnote 52

Although on the radio we do not see Holmes, his presence as source of the music is just as clear as if we did. Verma discusses how the radio acousmêtre operates in his analysis of the long-running series The Shadow, though his ultimate conclusion that the real acousmêtres are the sponsors (‘The acousmêtre is not the Shadow at all, but the Blue Coal Company sponsoring The Shadow in order to promote the sale of Pennsylvania anthracite’) is somewhat overly cynical in my view.Footnote 53 The sponsors of the show do not have enough of a foot in the dramas to be taken seriously as acousmêtres, but through an isomorphism with his musical instrument, Holmes is suspended over the entire dramatic enterprise of the 60 stories, keeping one foot inside the drama, and one foot outside it. He has the properties of ‘omnipotence’, ‘omniscience’ and ‘ubiquity’ that properly define the acousmêtre for Chion.Footnote 54 There are at least three different ways in which Holmes and his violin behave as acousmêtres, each of which deserves consideration.

Mendelssohn’s curtains

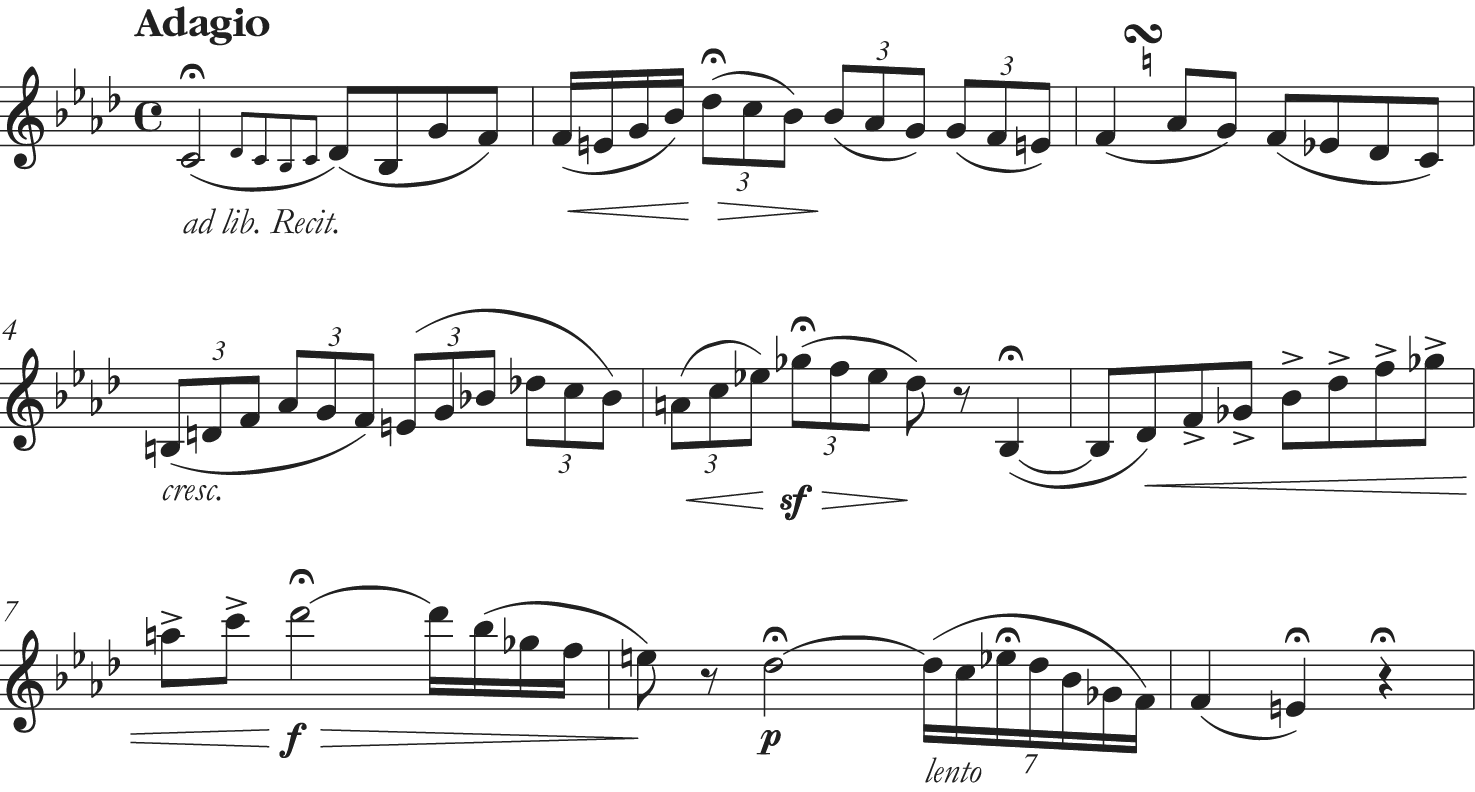

The violin plays the show’s characteristic signature tune, the unaccompanied introduction to Mendelssohn’s Violin Sonata in F minor, op. 4 (see Example 1). This is used as a frame for each story, bookending the drama with tortured chromatic twists and turns that embody Holmes’s complex nature, reminiscent of the theme from the Granada Television series (starring Jeremy Brett as Holmes and David Burke and Edward Hardwick as Dr Watson in the first and second series respectively). However, on one occasion Holmes actively plays this signature, after announcing at the close of ‘The Noble Bachelor’ that he intends to ‘while away these bleak, autumnal evenings’ and reaching for his violin. Here he steps forward as acousmêtre, and this draws the frame and the drama together. The same occurs in the Granada Television series when in ‘The Six Napoleons’ Holmes begins playing the violin signature tune to close the show.Footnote 55 This makes us wonder whether Holmes is always playing this signature theme, which normally exists outside the diegetic space of the 45-minute dramas.Footnote 56 The answer is that he probably is, but we have to suspend clear judgment. In ‘The Missing Three-Quarter’, to accompany the air of deep sadness at the episode’s close, Holmes and Watson discuss the case over the signature tune; they are in the countryside, miles from home, so there is no question of Holmes playing the violin at that time, and the diegesis splits into two temporalities, one framing the other.

Example 1 Mendelssohn’s Violin Sonata in F minor, op. 4, opening.

Chion claims that: ‘In radio, we cannot perceive where things “cut”, as sound itself has no frame.’Footnote 57 Yet sound does become this very framing device to these stories, putting Holmes the violinist, rather than Watson, in control of the narrative. This may seem surprising, because Watson so often narrates over Holmes’s violin playing. A very telling moment occurs in ‘The Red-Headed League’, when Conan Doyle places Holmes in a Sarasate concert at St James’s Hall. We imagine Holmes listening to Sarasate and listen with him to the first movement of Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto.Footnote 58 The concerto in the foreground ducks as Watson begins to narrate, describing Holmes’s introspective enjoyment of the concert. The concerto is seamlessly cut to adapt to the changes in Watson’s tone. As Watson recounts, ‘I have often thought that he was possessed of a dual nature,’ the lyrical Andante movement is heard, magically springing out of the Allegro molto appassionato first movement. Watson narrates further:

For myself, I felt his extreme exactness and astuteness in detection represented a reaction against the poetic and contemplative mood occasions such as the present brought to the fore. That the swing of his nature would shortly take him from extreme languor to devouring energy, promising an evil time for those he had set himself to hunt down.

This creates a link between Holmes’s dual personality and the dialectics within nineteenth-century symphonic forms. But this is not just a symphony; this is a concerto, where an individual of great virtuosity is placed centre stage. The curious result here, however, is that Holmes is passive (at least, he is listening rather than playing). And yet he is somehow in complete control of the narrative world, because the story and its music are about him. Notwithstanding Watson’s regular narration of text in the stories (reflecting, of course, the fact that Conan Doyle made Watson his mouthpiece), Holmes has ultimate control, because he is taking the lead role in enacting the dramas themselves, performing himself while controlling how Watson tells the story. Holmes’s musical utterances, in which his violin synecdochically stands for himself as narrative acousmêtre, gives him a direct voice, Holmes’s violin representing perhaps a counterpoint to Watson’s direct narration.

Violin bridges

The violin ‘bridges’ that ‘take us’ (as Coules often puts it in the scripts) from location to locationFootnote 59 reflect Holmes’s moods, to create what Chion calls ‘empathetic music’.Footnote 60 Holmes is telling us, in music, how he is feeling. For example, the low slump of lethargy and despondency in ‘The Reigate Squires’ is accompanied by Kreisler’s angular musical sighs from his Recitative and Scherzo which perfectly exemplify Holmes’s nervous exhaustion. On other occasions, whenever ‘the game is afoot’ we have the more energetic virtuoso passages from Paganini’s caprices acting as what Goffman calls ‘a sort of aural version of subtitles’.Footnote 61 In fact, it is no surprise, given that Holmes is often called a ‘sleuth-hound’, that when he follows Toby the sniffer dog in ‘The Sign of the Four’ or Pompey the beagle in ‘The Missing Three-Quarter’ the animals also run to Holmes’s frantic, virtuosic violin playing. These dogs represent Holmes, just as the violin does; they can therefore represent each other. But these acousmatic violin bridges also need to sew two scenes together, taking something from each, as Kremenliev outlined above. In some instances (‘Silver Blaze’, ‘The Naval Treaty’ and ‘The Illustrious Client’) we hear screams that fuse with a screeching violin which slowly calms the atmosphere and takes us to a new scene. In a different moment in ‘The Illustrious Client’, Holmes expresses the need for a ‘direct approach’ and the bridging music is extremely angular and tortured, showing us that this direct approach is impossible, as is confirmed by the game of intellectual cat and mouse that follows between Holmes and his antagonist. These links – much more subtle than the gongs that used to indicate scene changes in much of pre-war radio drama – all come from the magical commentary of Holmes’s violin, the grand acousmêtre, whose music occupies so many different diegetic positions.

Fantastic teasers; or, accompanying one’s special effects

Guido Heldt’s work on composer biopics suggests that, ‘The double role of a composer’s music as object and means of narration links the life and work in a myth-making (or more often myth-reinforcing) feedback loop.’Footnote 62 If we substitute ‘composer’ for ‘performer’ here (although we are told by Conan Doyle that Holmes is also a composer of no ordinary merit), we can acknowledge that the violin bores even deeper into Holmes’s soul through a split diegesis, in which ‘narrator’-Holmes plays the violin to accompany ‘actor’-Holmes’s speeches, now heard simultaneously, though at conceptually different times. There are four shows whose ‘teasers’ (the industry term for the attention-grabbing opening scene, heard before the signature tune and credit announcements) feature Holmes delivering key speeches that sometimes recur later in the main drama. In all cases, when the speech returns (that is, in its true setting) it is delivered purely without any background music or additional ceremony, but the teaser version is constructed magically, marked out as other-worldly and acousmatic through added music and reverberation effects on Holmes’s voice.

Merrison delivers such lines intimately, sometimes as a whisper, and yet the reverb effect projects them to the further-flung regions of the audio field, making him seem timeless, ethereal, almost godlike. In ‘The Final Problem’ there is no music, only the cold reverberation of Holmes’s voice (in this episode, Holmes faces death). In ‘The Blue Carbuncle’, the speech is accompanied by a warming yet plaintive improvisatory violin fragment, marked simply as ‘something eerie and mysterious’ in the script, which displays Holmes’s curiosity as he handles the famous gemstone: ‘Look at it. Just see how it glints and sparkles.’ This creates something similar to what Holly Rogers calls ‘sonic elongation’, when, ‘Noise from within the film’s world is broadened until it becomes unfamiliar: when source sounds abstract from their visual referents to take on musical form and texture.’Footnote 63 A similar effect again is employed in Michael Bakewell’s adaptation of Christie’s ‘The Mystery of the Blue Train’, when every unveiling of the famous ruby – ‘the heart of fire’ – is accompanied by highly refined violin harmonics that seem to zoom into the delicate, barely perceptible noises emanating from the intricate facets of the jewel, like fingers running the rim of a wine glass. As Holmes examines another realm of natural beauty in his famous speech from ‘The Naval Treaty’ (‘What a lovely thing a rose is …’), his violin soars into the highest echelons with the mysterious leaps and chromatic slides of the tenth variation of Paganini’s Caprice no. 24 in A minor, marking out that Holmes is taking time out from the reality of the case to explore the mysteries of nature.Footnote 64 In ‘The Three Garridebs’, Holmes’s opening speech explicating the Latin phrase ‘latis anguis in herba’ (‘there is a snake in the grass’) is underscored with similarly mysterious music, and although this speech never returns in the diegetic world, the episode closes with Watson spotting an adder, leading Holmes to ruminate upon the nature of fate: ‘To you, Watson, it’s like a sniggering schoolboy; to me it seems like a snake in the grass.’

In all four examples, there is a subjunctive kind of diegesis, in which the music creates a parallel universe of how the otherwise ordinary speech could have been delivered in a more interior (metadiegetic in Gorbman’s terms) world, through music. And it uses Holmes’s violin as narrator and romanticizer of his own life – something of which Holmes ironically always accuses Watson of being. It gives us a glimpse into Holmes’s inner world at things which Watson could not narrate for him and to which he has only limited access. When Stilwell coined the term ‘fantastical gap’ between diegetic and non-diegetic sounds, she described how she was pleased with the term, which was ‘particularly apt for this liminal space because it captured both its magic and its danger, the sense of unreality that always obtains as we leap from one solid edge toward another at some unknown distance and some uncertain stability’.Footnote 65 Even beyond the equivocal position of the music here as diegetic or non-diegetic, there is certainly much fantasy in these teasers, amounting to more than just the poetic magic of Holmes’s imaginative adoration of natural beauty (or ugliness in the case of the snake). In the gap between the two iterations of the same speech from different diegetic positions – one diegetic, one metadiegetic (or perhaps even non-diegetic) – there is the music.Footnote 66

Musical presence as lack

Chion describes how the ‘failure’ of talkies was that they filled the void of silence in which ‘desire had built its nest’.Footnote 67 The lack of integrated sound was fascinating to us, and we used our imaginations to fill the void. This fascination was stolen from us when sound was introduced. A radio-drama enthusiast may well feel the same about television’s visual field, which takes power away from the imagination, thus limiting our desires and fantasies. Music within radio dramas can fuel desire still further, and this desire plays itself out in the diegetic frame as well, reminding us of what the characters (and we ourselves) lack. Our individual fantasies, as well as those of the protagonists, thus supplement the drama we hear, guided by music.

The Tchaikovsky leitmotif: Holmes’s violin as Watson’s lack

The chromatic twists and turns of Mendelssohn’s signature tune can remind us that Holmes’s character is not straightforward; neither is his relationship with Watson. Without wishing to fuel the futile speculations about Holmes’s and Watson’s sexuality, it is safe to claim that the two men clearly love each other deeply, and both fulfil a certain lack in the other’s life. Watson is alone, homeless (in a sense) and drifting when he meets Holmes, who gives his life purpose again. This is offered musically in their meeting in ‘A Study in Scarlet’. When Watson recounts his war horrors as narrator in the episode’s teaser, the underscoring music is a piece of low, disturbing, dissonant, tortured, orchestral rumbling with only an intermittent flute to explore the upper register, and fragments of a violin line that seems to be trying to find its voice, distinct from the low orchestral conflict.Footnote 68 As described above, when Holmes and Watson begin sharing rooms, the first thing that Holmes does is to give Watson a demonstration of his prowess on the violin. In a sense, the sophisticated violin is the missing piece of Watson’s puzzle; it fulfils him.Footnote 69 This musical fulfilment cuts much deeper throughout the entire canon as the stories progress, using as a kind of leitmotif or signature tune for Watson’s relationships both with Holmes and with his romantic interests Tchaikovsky’s Sérénade mélancolique in B♭ minor for violin and orchestra, op. 26 (1875).

The melancholic B♭ minor theme (see Example 2) of this serenade is first heard as the signature tune of ‘The Sign of the Four’.Footnote 70 This, the second story in the canon, was directed by Ian Cotterell, who according to Coules possessed a great ‘love of music’.Footnote 71 The theme is first heard as an underscore to accompany Watson’s narration as he describes the dejection he feels when he first falls in love with their client Mary Morstan. As Watson turns away after taking her home, the script reads simply: ‘Music. Over it we move with Watson as he walks slowly to the carriage, opens the door, and gets in.’Footnote 72 Later, when Watson has declared his love, there is no underscoring, but we afterwards hear the violin theme played unaccompanied, and this is followed by ‘Come in Watson’ as we realize that this is Holmes playing. Holmes steps forward here as the musical narrator of Watson’s love life. Unlike Watson’s highly rich emotional world, Holmes’s is solitary, lonely, sparse. While Holmes possesses what Watson lacks, symbolically registered as the violin, Holmes has only the violin, while Watson has the richness of the orchestral accompaniment which, however, lies outside the Holmes–Watson relationship, belonging as it does to Watson’s more fully social existence.

Example 2 Tchaikovsky’s Sérénade mélancolique in B♭ minor for violin and orchestra, op. 26 (1875), opening.

In later stories, Watson adopts the lonely unaccompanied version when, during the period in which he believes Holmes to have been killed at the Reichenbach Falls, his wife Mary succumbs to death in ‘The Empty House’.Footnote 73 We hear Watson reading Holmes’s farewell letter, while the solo violin version of the serenade wafts through his memory (and ours). Watson is now doubly alone and has assumed a deep empathy with Holmes’s former solitary existence. In ‘Black Peter’ (after Holmes’s ‘reincarnation’), Watson is melancholy throughout, preoccupied with the anniversary of Mary’s death. When he stands at her graveside, we again hear the unaccompanied Tchaikovsky, referring back to ‘The Sign of the Four’. All Watson has left is Holmes’s violin playing to replace the richness of his former marital life. (Holmes even reports that he envies Watson because he himself cannot fall in love.) This solo version returns in the final adventure in the canon, ‘The Retired Colourman’, an episode in which Coules was briefed to make the episode ‘a real farewell’. When Watson enters 221b Baker Street to discover that Holmes has gone to live a new life in the Sussex countryside, a faint, half-remembered conversation is tinged with distant reverb to place us metadiegetically (in Gorbman’s sense) inside Watson’s memory. Beneath the unaccompanied Tchaikovsky, Watson remembers his first introduction to Holmes’s violin (‘Have you ever seen a genuine Stradivarius?’) and also recalls their last words together, woven together with this despondent theme. Watson is once again alone, and the excerpt is greatly elongated to keep compounding his sense of loss. After ‘The Sign of the Four’ this theme is notably never played again in the diegetic world and exists only in Watson’s memory, always underscoring his love, either for Holmes or for his own successive wives. But this is an acousmatic memory of something that had once been ‘visualized’, now moved to the metadiegetic. The script says simply: ‘The music cuts and so do the memories.’Footnote 74

Holmes as Wagnerian

This is not the only theme that speaks of the Watson–Holmes relationship. One of the richest musical set pieces is the reference to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in ‘The Devil’s Foot’. Coules claims: ‘I was keen to use music to evoke the bleakness and grandeur of the Cornish coast where Holmes finds himself an unwilling convalescent.’Footnote 75 That both opera and detective story are set in Cornwall is only the beginning of the marriage. Holmes is there in convalescence with Watson, and it is surely no coincidence that when using Wagner’s Tristan as underscore, the prelude from Act 3 is employed rather than the more recognizable Act 1. In Act 1, the famous opening yearning motif represents the Schopenhauerian gulf between Tristan and Isolde; in Act 3, Tristan is convalescing with his faithful aide Kurwenal – Tristan’s very own ‘Watson’.Footnote 76 Holmes again provides the musical narration as Watson does not know Tristan und Isolde and asks, ‘What do the words mean?’ Holmes then provides a translation of the Act 2 love duet (‘So stürben wir’) over the music of the Act 3 prelude. Coules admits that there is ‘more non-realism there, but the moment can take it’.Footnote 77 Ironically, for all that Watson’s fullness of love received full orchestration in the Tchaikovsky theme, it is Holmes who clearly has the knowledge of the repertoire of deep emotion. What then is the status of the music here? Perhaps it represents an unbridgeable gap both between Holmes and Watson as individuals and between them and the rest of the world. Music also represents the gap between Holmes’s inner knowledge of deep emotion and his real life, in which he is a ‘calculating machine’, as Conan Doyle puts it. There is also a gap – a ‘fantastical one’ – between levels of diegesis in the acoustic realm. When Holmes recites poetry from Wagner and we hear the orchestra, this is what he hears in his mind as a metadiegetic gesture (in Gorbman’s sense of music playing within the mind). This metadiegetic music also symbolizes here the fantasy that fills the void between the characters. Here, then, we might find a different type of ‘fantastical gap’, a rather psychoanalytical one, in which a psychological gap (or ‘lack’) which the characters feel is filled with musical fantasy.

This is not the first time that the Wagnerian world of Tristan has been used as an intertextual symbol of Holmes’s Sehnsucht. In ‘A Scandal in Bohemia’, Holmes recounts how he secretly listened – at a removal, then, of two layers of metadiegesis (in Winters’s use of the term) from the actual source – to Adler singing in her home. Playing up the angle that Adler is ‘the woman’, she sings Wagner’s Träume: Studie zu Tristan und Isolde from his Wesendonck Lieder (1857). Earlier, when Holmes’s client the King of Bohemia was reminiscing about Adler, his former lover, we heard her sing (metadiegetically) the same song (though a different part of it). In later listening outside her window, Holmes thus aligns his gaze upon Adler with that of the King, strengthening their mutual fascination with her. Wagner’s songs were dedicated to Mathilde Wesendonck, to whom he was amorously attached (extramaritally, of course) while writing Tristan. This particular song, with its ever-rising melodic lines, painfully reaching upwards for a point of satisfaction or repose, makes use of material from Act 2 of Tristan. The text speaks of dreams – ‘Tell me, what kind of wondrous dreams are embracing my senses, that have not, like sea-foam, vanished into desolate Nothingness?’ Again, however, Holmes is on the outside listening in (whereas the King was on the inside). All Holmes can do is dream outside Adler’s window. The music has a clear ‘visualization’, but it serves to highlight a fundamental blockage between Holmes and romantic enjoyment, just as romantic love was barred between Wagner and Mathilde Wesendonck. The music is present, but symbolizes an absence. This is also an example of music serving as an aural version (as it was originally designated, in fact) of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s ‘gaze’, so common in discussions of film since Laura Mulvey coined the term ‘male gaze’ to demonstrate that, in watching cinema from a male perspective, we objectify women.Footnote 78 Applying the concept to the acoustic realm, we can perhaps be truer to Lacan’s gaze, which can involve listening, reading or dreaming, and resides in the imagination. As Lacan makes clear, basing his concept on Sartre,

If you turn to Sartre’s own text, you will see that, far from speaking of the emergence of this gaze as of something that concerns the organ of sight, he refers to the sound of rustling leaves, suddenly heard while out hunting, to a footstep heard in a corridor.Footnote 79

If Lacan’s concept of the gaze is that the watcher (or listener) feels themselves objectified by an imagined gaze (something from another world that lies behind what can be actually seen or known), then Holmes is himself the objectified, powerless, mesmerized listener here; ‘the woman’ (Adler) is the singing subject, asserting full control of the gaze that, as Lacan puts it, ‘overwhelms him [Sartre for Lacan, Holmes for us] and reduces him to a feeling of shame’.Footnote 80 The power of her gaze is proved when she outwits Holmes, and she further escapes his narrative control by doing so, wielding a musical power much greater in its freedom than his solitary acousmatic violin. She has ousted Holmes as acousmêtre; she controls both his and the King’s imaginations through her music-as-gaze.

Mise en abyme: music as paradiegetic allusion

Following on from these Wagnerian associations, we now need to theorize this technique of using well-known music that comes with ready-made intertextual associations reflecting themes in Holmes’s world. The term ‘intertextuality’ has adopted many meanings since its use by Julia Kristeva in 1969, referring essentially to the reliance of any text on the presence of a network of other texts.Footnote 81 I imagine the term in the more specific and admittedly ‘narrower’ sense defined by Gérard Genette in 1982,Footnote 82 which employs it to mean plagiarism, quotation and allusion, particularly focusing on the last. Although there is room for the ubiquitous terms ‘allusion’ or even ‘intertextuality’ to be sustained, we need to emphasize the significant relationship of these to the broader diegetic structure. A similar concept to this may be what Kassabian called ‘affiliating identifications’ whose ‘ties depend on histories forged outside the film scene’.Footnote 83 However, Kassabian discusses the associations brought by popular-music genres rather than specific signifiers of other narratives. Describing a different but equally related model of engagement, Rogers talks of ‘sonic aporia’ (moments when there is a gap between what we ‘see’ – or in radio perhaps know to be happening – and what we ‘hear’), which activates us to align our pre-existent knowledge with the sounds we hear and to fill the space of the aporia with our pre-associative connections. This ‘develops horizontally on its own terms, as though referring to an alternative, or parallel, world to the one we see’.Footnote 84

In these radio dramas, certain techniques are used in order to invite into the frame a parenthetical musical drama which is based on resemblance and opens us up to something that we could call paradiegetic. Genevieve Liveley defines paradiegesis as ‘digressions which do not form part of the central narrative plot […] but which do form part of the story (or fabula)’, citing moments that ‘happened earlier’ in Homer’s Iliad such as analepses or flashbacks, nostalgic stories, histories of objects, background episodes or myths, and so on.Footnote 85 The prefix ‘para-’ has a broad constellation of meanings and associations, including ‘alongside’ or ‘adjacent’, but can also serve to mean ‘resembling’ or ‘similar’, the latter of which is particularly important to us. While paradiegesis primarily refers to two intertwined dramas, one in some way parenthetical to the other, in these radio dramas there is a strong coefficient of intertextual allusion to pre-existing secondary narratives (generally having ‘happened earlier’) that are brought into the primary frame, where they work alongside it, comment upon it through comparison (or rather invite us to find comment upon it), elucidate it and draw out new meanings, creating twin narratives that develop symbiotically. And, crucially for us, in these radio dramas, such paradiegetic worlds are invoked by purely musical means.Footnote 86

The Tristan connection is central to ‘The Devil’s Foot’ and is explicated in the dialogue, but there are many more surreptitious instances of this technique, each with different strategies for integrating with and commenting upon the main dramatic plot. These often, though not always, produce paradiegetic mises en abyme – stories within the stories – which, because they are musicalized rather than verbalized, are told only through music. The same happens, of course, in film and television, though in the parallel adaptations of Holmes stories for these media, this tends to happen through a much more basic form of allusion. In the Granada series, we hear Leporello’s famous ‘catalogue aria’ (‘Madamina, il catalogo è questo’) from Mozart’s Don Giovanni underscoring Baron von Gruner as he pastes a photograph of his latest sexual conquest into his perverse book of ‘collected women’. Tristan itself is often evoked, for example, in ITV’s adaptation of Christie’s Five Little Pigs, or the episode of Upstairs, Downstairs in which Lady Bellamy has scandalously had an affair with a younger artist, or even in the Sherlock Holmes adventure ‘The Red Circle’, in which a lover is murdered backstage at the opera. It is worth considering, however, that although this happens often in film and television, the high concentration of musical intertextuality in radio, and its elevation to something more structural to the narrative (paradiegesis), may be a response to the fact that other avenues for drawing in connections – such as a character reading a particularly relevant book or standing in front of a relevant theatrical poster – cannot be ‘shown’ visually. In ‘The Golden Pince-Nez’, for example, we cannot see that the main character is reading Anna Karenina, and therefore the connection needs to be brought out in the script, which thematizes the connections between the ‘Anna’ in both stories, adding also to the Russian flavour of the Holmes adventure (whereas the Granada series has a whole visual dimension that more subtly plants Russia in our minds – revolutionary banners in Cyrillic script, the characteristic winter hats, and so on). In this instance, the allusions are marked through literature, and are foregrounded paradiegetically in order to hammer the connection home. Along with this, many musical allusions give us an insight into how radio drama relies heavily on the technique. While the instances outlined below are certainly fascinating examples of intertextual allusion, more often than not the allusions or references become conjoined with the unfolding narrative through a paradigetic musical strategy.

A paradiegetic force of destiny

References to opera are quite common. An instance in ‘The Red Circle’ does not even require the music itself to be heard, when Holmes teasingly drives Watson to Covent Garden for an appointment with ‘a mysterious murder […] a crime of jealous passion and revenge, an Italian stabbed to death’. Of course, Holmes reveals that they are about to see Verdi’s Rigoletto, whose plot contains the same elements as those that we have heard in the adventure.Footnote 87 A less accessible instance of this kind of paradiegetic mise en abyme occurs in the Italian-mafia-driven plot of ‘The Six Napoleons’, whose dramatization alludes to music from Verdi’s La forza del destino, drawing its family feuds and famous knife fights into Holmes’s adventure. And the frequent intercutting of the developing Verdian musical narrative acts symbiotically – or paradiegetically – with Conan Doyle’s parallel narrative. We first hear the overture’s ‘fate’ theme, with its famous tragic octave Es in the brass, leading up to a catastrophic diminished-seventh chord that coincides with a melodramatic female scream of ‘Noooo!’ that capsizes the melodramatic operatic world (with vast chunks spoken in Italian) back into the Holmesian drama. The fact that the narration also makes clear that the screaming female character had been at the opera while a precious pearl was stolen binds together the two worlds surrounding the sonic aporia.

Later on, this interrupting diminished seventh is ‘corrected’ to cadence properly as the case is resolved and Lestrade declares, ‘That was first class!’ The joke here is that we might instantly assume the music to be diegetic, Lestrade commenting as the friends leave the opera together, when in fact it subsequently emerges that he is talking about Mrs Hudson’s cooking, and dinner has just finished. The opera was not in the diegetic frame after all. In terms of the drama’s diegesis, this is perhaps closest to how Giorgio Biancorosso views shifts from one diegetic level to another as a kind of ‘epistemological joke’.Footnote 88 The joke, which can work only in radio, is clearly at Lestrade’s expense; Holmes – qua musical narrative agent – views life through the lens of operatic drama, while Lestrade is the uncultured Scotland Yard official. This kind of game is more conducive to radio than it is to visual media, because radio can conceal more than film, and can conceal for longer. The moment of ‘visualization’ is easier to withhold in the dark. The idea of the ‘play within a play’ in this story is brought out more fully as this episode progresses, when Holmes takes Watson through the squalid streets and a plaintive, slow woodwind section plays a nostalgic theme in A minor from Verdi’s overture, with fragments of the main ‘fate’ motif woven in. Holmes calls this realm of the Italian immigrants ‘a city within a city’, a poignant reflection of the ‘play within a play’ now figured as the gap between grand opera and squalid reality.

The paradiegetic red herring

An instance of music having a subliminal but directly paradiegetic relevance to our experience of the mystery itself is heard at the opening of ‘The Speckled Band’. While the main protagonist, Miss Helen Stoner, is writing a letter (and is about to hear her sister Julia scream from the next room), we hear the violent opening violin solo from Ravel’s Tzigane (1924 – marginally anachronistic). This rhapsodic composition sets the tragic tone, continued in the sound of the harsh scratching from Miss Stoner’s quill pen.Footnote 89 The music is Gypsyesque (the title Tzigane being a play on the French gitan or tsigane, as well as the Hungarian cigány) and subtly implants the ‘red herring’ of the camping Gypsies who are blamed for the sister’s dying reference to a ‘speckled band’ (a reference to their bandanas). This appears to be non-diegetic, because the music is not heard by Stoner herself. However, the main signifier of death in the story is the sound of a low whistle that the lady can hear at night, which could again have something to do with the Gypsies’ music (she claims, ‘I believe they have a way of communicating with whistles’).Footnote 90 This alternative to the Gypsy whistle which would be diegetic is an instance of a subjunctive diegesis – a virtual world. This is music that is not heard by the characters but stands in for music that is heard and has the same effect on the characters within the diegetic frame that it can have on us, the radio listeners. Note also that even without identifying the piece as Ravel’s Tzigane, its Gypsy topics are easily identifiable as such by means of the dramatic, snapped rhythms, the Hungarian scales, and so on. Another layer of subtlety is that this is a false lead; the Gypsies have nothing to do with the crime. The subliminal musical red herring could well dupe listeners, just as it dupes the characters in the tale.

Paradiegetic parlour songs

It is important that listeners without knowledge of the repertoire should not be alienated; each instance has to work on its own terms. Supplementary layers of meaning must remain supplementary, however enriching they might be. Some of these paradiegetic mises en abyme are quite abstruse, but others are transparent and self-revealing – not so much allusions as direct comparisons. Coules admits to having most musical fun with his dramatization of ‘The Solitary Cyclist’ and must have similarly enjoyed ‘Charles Augustus Milverton’ and ‘The Valley of Fear’ for the use of near-complete parlour songs that are fully ‘visualized’, but which give us a form of musical dramatic irony if we pay heed to them, for they always comment on the unfolding mystery. Reading ‘The Solitary Cyclist’, Coules came across the lines: ‘Mr Carruthers takes a great deal of interest in me. We are rather thrown together. I play his accompaniments in the evenings.’Footnote 91 Coules asks us, ‘What more could an audio dramatist ask for?’Footnote 92 and made the young music teacher, Miss Smith, and her new employer, Mr Carruthers, a regular source of musical intermezzo. Coules claims: ‘I could break up what limited action the story contained with snatches of Victorian ballads and after-dinner songs, and what’s more, I could choose pieces that would actually comment on the plot as it progressed.’Footnote 93 In these songs, the intimacy between employer and employee is clear, but even beforehand, the difficult realities of the relationship are given in musical terms. Carruthers had been part of a plot to marry Miss Smith for her inheritance, but through their musical association begins genuinely to love her and tries to call a halt to the plot. The warning signs are there for us listeners, but should have been clear to her too, if only she had listened to the music she was playing. But they are not alone in the household. Miss Smith’s first duty is to Carruthers’s child, young Sarah. Sarah tells Miss Smith that her mother used to accompany her father before she died, placing Smith in the maternal role. Likewise, Miss Smith’s father died, and thus Carruthers seems to be playing father to both females. Miss Smith is playing the role of mother and (would-be) lover at the same time, forming what Carl Jung might call (apropos of Freud’s ‘Oedipus complex’) an ‘Elektra complex’, which confuses fatherly love with romantic love.

Love is certainly symbolized in the act of accompanying the singing from the piano, as is clear from the dialogue when Miss Smith claims to love providing accompaniment: ‘two elements that go together to make a greater whole’. It is no coincidence that the first song they perform to themselves (and to us) is Home, Sweet Home, as it establishes the new domestic triangle. Miss Smith soon plays a tune on the piano that Sarah in her naive way describes as ‘lovely and sad at the same time’. The tune she plays is the antecedent of the melody from Then You’ll Remember Me, but halts abruptly. Those who know the lyrics of the song will know that they predict a bleak future, with warm remembrance of the present:

Miss Smith’s abrupt abandonment of this song perhaps shows her disavowal of what she unconsciously knows to be true – that she is in the midst of deceit. Once the cat is out of the bag, and Carruthers’s role in the plot exposed, we hear a more complete version of the song with Carruthers (played by the actor Denis Quilley) completing the vocal line. This is a remembrance, of course, ‘visualized’, but only in retrospective metadiegetic memory. Coules notes that the song Daisy Bell included ‘a clear warning that the singer might well prove to be less than stable’ (‘I’m half crazy, all for the love of you’),Footnote 94 but in choosing to pepper the drama with The Gypsy’s Warning he makes further warnings:

Do not trust him, gentle lady, though his voice be low and sweet,

Heed not him who kneels before you, gently pleading at thy feet.

Now thy life is in its morning, blight not this, thy happy lot,

Listen to the Gypsy’s warning, gentle lady trust him not

[…]

I would shield thee from all danger, shield thee from the tempter’s care,

Lady, shun that dark-eyed stranger, I have warned thee, now beware.

The irony is that while Carruthers is warning Miss Smith in song, he is warning her about himself. Fortunately, Miss Smith heeds these warnings and retains her independence, which is also registered musically. Just before Carruthers proposes marriage, they perform ‘Drink to me only with thine eyes’, but Miss Smith’s musical independence is shown when she slips into a lengthy imaginative piano postlude of the sort that Schumann employs in songs from Dichterliebe. This has a resistant effect, showing that she is ultimately going to be independent from her employer’s control. Her unspoken answer, pre-emptive to the question, is clear through her playing.

As mentioned, the songs break up the drama and offer a kind of diegetic time loop; they are really happening, but not now. The final song (Then You’ll Remember Me) makes this clear and is entirely retrospective. Described in the script as ‘plaintive, sincere and tragic’, this is the most obviously atemporal paradiegetic moment; it is the one when she appears closest to her temporary father’s voice after the happy period is over. It was a song too personal for Carruthers to sing with her in real life, and was thus halted earlier, but now they reach a musical climax in her fantasy space.

Among Holmes’s most morally controversial actions (along with cocaine usage, deceiving Watson into thinking he is dead, letting criminals off ‘scot-free’ and entirely forgetting Watson in ‘The Dying Detective’) is the act of seducing his blackmailer-enemy’s maid, Aggie, away from her long-standing suitor, Harry. Holmes pitches woo and then abandons her in order to gain admittance into the abominable Charles Augustus Milverton’s house. There is no reference in Conan Doyle’s text to the musical aspects of his courtship, but under Coules’s dramatization music plays its role in the duplicity. A hint of tragic irony is given when the pub singers gather around the out-of-tune piano to sing Waiting at the Church – a song about abandonment. The courting couple step outside and the diegetic source becomes immediately quieter, allowing it to work subliminally now. We know that the song is diegetic because of the ‘realistic’ delivery, but it is also revealed to have been digested by Aggie as she begs, ‘Harry, you wouldn’t do that to me would you? You may not be much but you’re all I’ve got.’ The tables turn when Holmes enters later in the episode, disguised as a plumber – with plenty of jokes about the contents of his toolbox! The song sung along with the out-of-tune piano that accompanies Holmes’s blunt intrusion into the relationship is The Daring Young Men on the Flying Trapeze. This song represents Holmes’s ability to swoop in and steal ‘the girl’ right under Harry’s nose. The lyrics speak of a lover jilted for a trapeze artist (‘And my love he purloined away’). These songs are fully ‘visualized’ but contain within them the non-visualized aspects of the mise en abyme. They exist in the now but play out their dramas in the main diegetic space at different speeds, or on Winters’s ‘metadiegetic’ planes, happen paradiegetically to the main drama.

‘The Valley of Fear’, as noted by Enyd Williams (see note 20 above), is another story full of musical set pieces, following cues given in the novel itself. Music here ameliorates a fundamental problem with the four long Sherlock Holmes stories, which is that they are essentially two stories in one; three of the four have lengthy flashbacks.Footnote 95 The character in the flashback whom we follow most closely in ‘The Valley of Fear’ is as duplicitous as the singing characters in the stories just discussed. Birdy Edwards from Pinkertons’ Detective Agency is disguised as John McMurdoe in order to infiltrate a corrupt lodge of Freemasons. Part of Edwards’s strategy for winning the trust of the crime boss McGinty is his singing of patriotic songs at their meetings. As in ‘The Solitary Cyclist’, the songs are ‘visualized’ but contain narrative elements that play out paradiegetically. The favourite choice of song for the Irishman (other than Danny Boy) is ‘The minstrel boy’, commencing, ‘The minstrel boy to the war is gone / In the ranks of death you’ll find him’, and culminating in the stirring line, ‘Thy songs were made for the pure and free / They shall never sound in slavery.’ Iain Glen, the actor and singer, fills the space with his big finish to rapturous applause, the irony being that he is singing of how he is bringing down the organization, and the organization itself is loving every minute of it – a paradiegetic form of dramatic irony. But from the perspective of the visualized frame, the interesting aspect is that the performances are still framed by Holmes as musical acousmêtre, even though neither Holmes nor Watson could know of their existence because the songs are part of the flashback. The songs are not in Conan Doyle’s scripts, and we must assume that these moments of flashback harken back either to a possible past imagined by the detectives or to an accurate past from which the detectives are alienated. The accuracy of these flashbacks is beyond Holmes’s (and our) power to verify, so it would be impossible for these songs to enter Holmes’s diegetic space – either Holmes-the actor’s or Holmes-the narrator’s. And yet, when Holmes is slipping back into melancholy at the close of the case, the music traverses this impossible space when Holmes himself, after warming up his violin, plays ‘The minstrel boy’ in a minor key. Even here, however, there are further ‘fantastical gaps’ to be crossed, as Holmes’s violin melody eventually becomes accompanied by an ‘impossible’ piano (who is playing it?).Footnote 96 Holmes therefore steps into the flashback frame itself (which he could know only through his musical imagination), musically substituting himself for Pinkerton’s detective through a close musical empathy for the role which, by solving the case, he has earned the right to assume. Unless we are to suspend our belief about the entire diegetic situation, the only conclusion we can draw in the sphere of reality is that the flashbacks were happening in Holmes’s own mind.

Holmes, the paradiegetic priest

A particularly well-chosen piece of precomposed music is the Queen of the Night’s aria from Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte, used to accompany the regular flashbacks of Mrs Ronder, the much-abused wife of a circus ringmaster in ‘The Veiled Lodger’. The reference is explained towards the end of the drama, in a flashback of sexual abuse during which the feared Mr Ronder dubs his abused wife ‘queen of the night’. She was a circus entertainer, now reduced to a veiled creature living in the shadows following a tragic disfigurement caused by a circus lion during an incident in which her husband was killed – so that she is now properly ‘queen of the night’. One of Mozart’s subtlest twists in Die Zauberflöte is that our initial perceptions of Sarastro (as villain) and the Queen of the Night (as force of good) turn on their heads, which her furious aria of rage and revenge brings to the foreground. Likewise, this theme, used partly as the melancholic leitmotif of her past, shows ultimately that she was a murderess rather than (just) a victim. However, the music is played on the solo violin in a sorrowful, reflective mood. We may well feel that, even in her flashbacks, it is Holmes who is playing, intruding into her secret narrative space as part of his strategy for taking musical narrative control. This view is heightened when the music finally increases in volume, appearing to cross into the ‘visualized’ frame of Holmes’s drawing room as Holmes and Watson finally reflect on the case.

Holmes’s role as musical narrator is undercut in this case, however, because he is merely a confessor; he solves nothing. Mrs Ronder describes choosing Holmes to hear her story rather than a priest or a policeman, because he acts as both. Holmes is granted powers of absolution, but is ousted as true narrator because Mrs Ronder narrates through him, musically and textually, relying on him to be her proxy. Once again, recalling the first story in which Holmes is famously outwitted ‘by a woman’ (Adler), Holmes is also out-narrated by one here. However, the fact that her character is produced as a musical representation of what men say about her (her husband called her ‘queen of the night’; Holmes plays the same tune) is embodied for me in the touching pathos of the performance, now rendered as a spectre of what was once, in Mozart’s drama, the most extravagant showstopper.

Case closed?

All good things come to an end. In the chronologically final adventure, ‘His Last Bow’, Holmes returns from retirement to penetrate an espionage ring during the First World War.Footnote 97 As we hear about both his and Watson’s adaption to the ‘modern age’, Watson gets into his car to visit Holmes in Sussex, and we hear a piano rag. This and the Siegfried Idyll are the only musical excerpts in the show; gone is the comforting sound of Holmes’s fireside violin playing, and gone is his ability to act as the grand acousmêtre. As he himself declares, it is not his world any more. He has laid down his violin.

Perhaps, though, the most poignant musical moment in the entire canon occurs outside the canon itself. Adopting titles of cases to which Conan Doyle tantalizingly alludes within the stories, Coules wrote four highly successful series of additional cases himself, The Further Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, with Andrew Sachs replacing Michael Williams as Watson. The final episode, ‘The Marlbourne Point Mystery’, recorded in December 2009, says farewell via music in ‘the final scene’.Footnote 98 The script notes: ‘[Holmes] briefly checks the tuning, then begins to play Wagner’s “Song to the Evening Star”.’ Watson remembers Holmes’s earliest performance, saying, ‘You played that for me just a few days after we moved in here.’ Then Holmes strikes ‘a tremulous chord’ and makes a touching speech to Watson about how they have become immortal through Watson’s stories. Apparently, there were tears in the recording studio when the final lines were delivered, and it is only fitting that music, which had taken a lead role in narrating the entire series, be central to this closing scene as the characters reflect on their own narrative agency.

The music of the series under discussion has helped us to recalibrate theories of audiovisual media to the audio-imaginary medium of radio drama. This has involved our returning traditionally audiovisual terms – such as ‘acousmatic’ and even, en passant, Lacan’s ‘gaze’ – back to their lost acoustic origins, unlocking new meanings by substituting the visual for the imagined-visual, which is at the very heart of radio listening: ‘As a little boy in Tampa once said while watching a television story, “You know, mamma, I like stories better on radio ’cause the pictures up here [pointing to his head] are better.”’Footnote 99 Perhaps the main difference between audiovisual drama and radio drama, my analysis has aimed to show, is that radio keeps us ‘acousmatized’ for longer, suspending us in an acousmatic zone without clear ‘visualization’. ‘Visualization’ in radio is always imaginary in any case, but can be achieved in acoustic terms, and a musical director can toy with our perceptions perhaps more profoundly there than they can in film. Music is also easier to foreground in radio than it is in film, where filmgoers always have the visual field to demand their primary attention, and it thus achieves a heightened intensity.