1. Introduction

Mercury (Hg) emissions associated with the emplacement of Large Igneous Provinces (LIPs) were first recognized by Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp (Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012), who showed a large Hg spike associated with the Siberian Traps eruptions. This event was coincident with the Latest Permian Extinction (LPE), the largest extinction in Earth's history that had a devastating impact on both terrestrial and marine ecosystems (Erwin, Reference Erwin2006). High Hg loading associated with the Siberian Traps has been supported by a similar Hg spike at the LPE boundary in Spitsbergen (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015). Recurrent Siberian Trap volcanism may also have influenced Hg loading during the Smithian/Spathian Extinction in the Sverdrup Basin (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b). While these initial studies are focused on the sedimentary records from NW Pangea, the global extent of Hg loading related to Siberian Trap volcanism has yet to be demonstrated. However, subsequent work has shown similar Hg anomalies associated with other LIP events such as the Cretaceous–Palaeogene transition (Sial et al. Reference Sial, Lacerda, Ferreira, Frei, Marquillas, Barbosa, Gaucher, Windmöller and Pereira2013, Reference Sial, Chen, Lacerda, Peralta, Gaucher, Frei, Cirilli, Ferreira, Marquillas, Barbosa, Pereira and Belmino2014; Silva et al. Reference Silva, Sial, Barbosa, Ferreira, Neumann, De Lacerda, Bojar, Melinte-Dobrinescu and Smit2013) related to Deccan Trap volcanism.

Hg is extremely toxic to life. This toxicity, combined with the ease of transport over long distances and persistence of Hg in the environment, makes modern anthropogenic mercury emissions the subject of significant global concern (AMAP, 2011). The two largest natural source of Hg to the environment are volcanic emissions and natural coal combustion (Pirrone et al. Reference Pirrone, Cinnirella, Feng, Finkelman, Friedli, Leaner, Mason, Mukherjee, Stracher, Streets and Telmer2010). These sources release Hg to the atmosphere where it can be globally transported prior to deposition in terrestrial and marine environments. In the marine environment, organic matter and clay minerals scavenge Hg and transport it to the sea floor to become fixed in bottom sediments (Cranston & Buckley, Reference Cranston and Buckley1972; Andren & Harriss, Reference Andren and Harriss1975; Lindberg, Andrenson & Harrisson, Reference Lindberg, Andrenson, Harrisson and Cronin1975; Turner, Millward & Le Roux, Reference Turner, Millward and Le Roux2004; Gehrke, Blum & Meyers, Reference Gehrke, Blum and Meyers2009). The control of primary productivity on Hg sequestration is shown by the close relationship between sedimentary organic matter and Hg in modern (Outridge et al. Reference Outridge, Sanei, Stern, Hamilton and Goodarzi2007; Stern et al. Reference Stern, Sanei, Roach, Delaronde and Outridge2009; Sanei et al. Reference Sanei, Outridge, Stern and Macdonald2014) as well as ancient sediments (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b).

Modern volcanic eruptions have a significant Hg flux that produces global Hg anomalies (Slemr et al. Reference Slemr, Junkermann, Schmidt and Sladkovic1995; Slemr & Scheel, Reference Slemr and Scheel1998; Schuster et al. Reference Schuster, Krabbenhoft, Naftz, Cecil, Olson, Dewild, Susong, Green and Abbott2002; Pyle & Mather, Reference Pyle and Mather2003). Hg is sourced from both volcanic gases as well as from rock units intruded by magma (Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp, Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012, Reference Sanei, Grasby, Beauchamp, Blais, Rosen and Smol2015; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015). During LIP events emission rates would greatly exceed normal Hg release (Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp, Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015), such that the normal marine buffering control on Hg can be potentially overwhelmed (Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp, Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b) and be recorded as an Hg spike in the sediment record. For instance, Grasby et al. (Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015) estimated that the Siberian Traps may have released up to 9.98 Gg a–1 Hg, or 400% above modern natural emissions. In comparision, the modern anthropogenic Hg emissions that roughly equal natural emissions are the subject of global concern over their impact on marine and terrestrial ecosystems. Hg anomalies formed at the time of LIP eruptions therefore suggest that: (1) Hg could be an effective marker in the geological record of periods of enhanced volcanic activity; and (2) LIP eruptions could potentially release toxic amounts of Hg to the environment. Such a scenario would add to the variety of kill mechanisms already associated with major volcanic eruptions (Keller & Kerr, Reference Keller and Kerr2014), as well as providing a direct link between terrestrial and marine extinction.

To further the assessment of Hg in the geological record, we examined the Permian – Early Triassic record at the Festningen section in Spitsbergen (Fig. 1). This well-known location records the LPE (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015; Wignall, Morante & Newton, Reference Wignall, Morante and Newton1998) as well as evidence for the earlier Capitanian Crisis (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Wignall, Joachimski, Sun, Savov, Grasby, Beauchamp and Blomeier2015) and Smithian/Spathian Extinction (Wignall et al. this volume), all of which have been linked to periods of major volcanic activity. Of these recent studies, the Hg record at Festningen has only been examined in a narrow (40 m) zone straddling the LPE boundary (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015). In this paper we examine the Hg record at Festningen over 600 m of section, spanning middle Permian – Lower Triassic deposits, representing c. 12 million years of Earth's history.4.

Figure 1. Map showing location of the Festningen section on Spitsbergen (base of section is located at 78.0950°N, 13.8240°E (WGS84 datum).

2. Study area

The Festningen section is located at Kapp Starostin, Spitsbergen (Fig. 1). The c. 45° east-dipping beds occur along a low-elevation sea cliff of c. 7 km in length. The section provides a near-continuous exposure of Carboniferous–Cenozoic strata, from Kapp Starostin to Festningsdodden, deposited in a distal broad epicontinental shelf setting on the north-western margin of Pangea (Wignall, Morante & Newton, Reference Wignall, Morante and Newton1998; Stemmerik & Worsley, Reference Stemmerik and Worsley2005; Blomeier et al. Reference Blomeier, Dustira, Forke and Scheibner2013). During Permian time Spitsbergen was at a palaeolatitude of c. 40–45°N (Golonka & Ford, Reference Golonka and Ford2000; Scotese, Reference Scotese2004).

The Kapp Starostin Formation was deposited during a period of passive subsidence that followed a major relative sea-level drop at the lower–middle Permian boundary (Blomeier et al. Reference Blomeier, Dustira, Forke and Scheibner2013). Deposition of widespread heterozoan carbonate (Vøringen Member) occurred during Roadian time, followed by the progradation of heterozoan carbonates and cherts over much of the Barents Shelf and Svalbard (Blomeier et al. Reference Blomeier, Dustira, Forke and Scheibner2013). Spitsbergen shares a similar depositional history to the palaeogeographically adjoining Sverdrup Basin (van Hauen, Degerböls and Trold Fiord formations; Beauchamp et al. Reference Beauchamp, Henderson, Grasby, Gates, Beatty, Utting and James2009; Fig. 2). Approximately 40 m below the contact with the overlying uppermost Permian – Lower Triassic Vardebukta Formation, fossiliferous carbonates of the Kapp Starostin Formation transition to spiculitic chert of late Permian age (Blomeier et al. Reference Blomeier, Dustira, Forke and Scheibner2013). These later Permian chert beds are considered equivalent to the Black Stripe and Lindström formations of the Sverdrup Basin (Beauchamp et al. Reference Beauchamp, Henderson, Grasby, Gates, Beatty, Utting and James2009). The Vardebukta and overlying Tvillingodden formations are dominated by shale, siltstone and minor sandstone of Early–Middle Triassic age (Mørk, Knarud & Worsley, Reference Mørk, Knarud, Worsley, Embry and Balkwill1982), equivalent to the Blind Fiord Formation of the Sverdrup Basin (Embry, Reference Embry and Collinson1989). The basal c. 6–7 m of the Vardebukta Formation is latest Permian in age (Wignall, Morante & Newton, Reference Wignall, Morante and Newton1998; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015).

Figure 2. Palaeogeographic map (after Embry, Reference Embry, Vorren, Bergsager, Dahl-Stamnes, Holter, Johansen, Lie and Lund1992) showing relative location of Sverdrup Basin and Spitsbergen. Inset map (after Scotese, Reference Scotese2004) showing location on NW Pangea.

3. Methods

A detailed sample suite was collected from 100 m below the Kapp Starostin/Vardebukta contact to 500 m above. Sample spacing varied from 1–2 m away from the contact to a higher density of 20–50 cm spacing from c. 40 m below to 19 m above the top of the Kapp Starostin Formation. Samples were recorded in metres above (positive) and below (negative) the last chert bed that defines the top of the Kapp Starostin Formation. Weathered surfaces were removed and then samples were collected from an isolated layer no greater than 2 cm thick. In the laboratory, any remaining weathered surfaces were removed and fresh samples were powdered by agate mortar and pestle.

Total organic carbon (TOC) was measured using Rock-Eval 6©, with ±5% analytical error of reported value, based on repeats and reproducibility of standards run after every fifth sample (Lafargue et al. Reference Lafargue, Espitalité, Marquis and Pillot1998). Elemental determinations were conducted on powdered samples digested in a 2:2:1:1 acid solution of H2O–HF–HClO4–HNO3, and subsequently analysed using a PerkinElmer Elan 9000 mass spectrometer with ±2% analytical error. Hg was measured at GSC-Atlantic by LECO® AMA254 mercury analyser (Hall & Pelchat, Reference Hall and Pelchat1997) (±10%). δ13Corg was determined on samples washed with hydrochloric acid, and rinsed with hot distilled water to remove any carbonate. δ13C was measured using continuous-flow elemental-analysis isotope-ratio mass spectrometry, with a Finnigan Mat Delta+XL mass spectrometer interfaced with a Costech 4010 elemental analyser with combined analytical and sampling error of ±0.2‰.

Analytical results from a total of 341 samples used in this study are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Geochemical data from the Festningen section. Depths are measured relative to the Latest Permian Extinction (LPE) Boundary marked by the top of the Kapp Starostin Formation. ND – not determined.

4. Results

4.a. Organic carbon

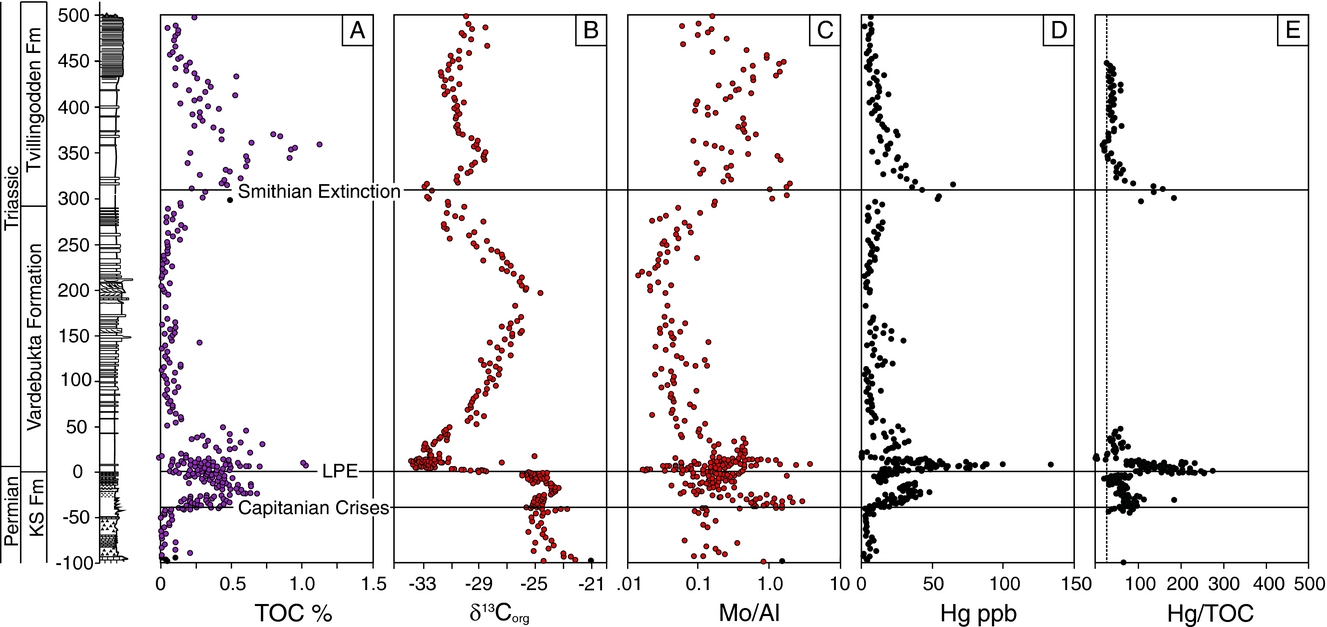

The organic carbon record, expressed as percent TOC, shows low values (<1% TOC) overall (Fig. 3a). There is an increase in TOC at –40 m. Based on brachiopod, Sr isotopes records and magnetostratigraphy data, Bond et al. (Reference Bond, Wignall, Joachimski, Sun, Savov, Grasby, Beauchamp and Blomeier2015) argue that the –40 m level is around the middle Permian extinction level at Festningen. The TOC values decline again leading up to the LPE boundary, where there is a second brief increase in TOC just above the LPE. For the remainder of the section, TOC values in the Vardebukta Formation are <0.2%. At these low values the accuracy of Rock-Eval results decreases, however data are plotted in Figure 3a to illustrate the overall low TOC values through this interval. The TOC values increase again in the basal Tvillingodden Formation, before dropping to low values in the upper 100 m of section.

Figure 3. Plots of geochemical data from Festningen, showing: (a) percent total organic carbon (TOC); (b) carbon isotope values for organic carbon; (c) Mo normalized by Al; (d) Hg values; and (e) Hg normalized by TOC (the Hg/TOC values are only shown for values of TOC > 0.2%; below that value Rock-Eval analyses provide less accurate results that are magnified in calculated ratios).

Rock-Eval 6© results also provided information on thermal maturation and indicated that organic matter in the shales have never been heated past the upper end of the oil window, and consequently the stable isotope values of organic carbon were not thermally altered (Hayes, Kaplan & Wedeking, Reference Hayes, Kaplan, Wedeking and Schopf1983). The only exception is a local thermal anomaly associated with a sill emplaced at c. 19 m that does not extend beyond 5 m of the sill boundary (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015).

4.b. Carbon isotope record

Portions of the organic carbon isotope curve (δ13Corg) at the Festningen section have been reported in previous studies, including middle–upper Permian sediments (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Wignall, Joachimski, Sun, Savov, Grasby, Beauchamp and Blomeier2015), across the Latest Permian Extinction event (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015) and sediments of Early Triassic age (Wignall et al. this volume). The combined δ13Corg curve is provided here (Fig. 3b) for comparison with both organic carbon isotope data from NW Pangea and the global inorganic carbon isotope record. The δ13Corg data from Festningen show initially relatively stable values of c. –24‰ through the middle–upper Permian sediments, with a relatively minor negative shift at c. –40 m. At the top of the Kapp Starostin Formation, carbon isotope values show the onset of a pronounced 10‰ negative shift through the basal Vardebukta Formation sediments (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015). After this point there is a progressive recovery through the next 200 m, followed by another progressive negative shift to a minimum at c. +300 m which is followed by an unstable period through the remainder of the measured section (Wignall et al. this volume).

4.c. Molybdenum

Similar to the carbon isotope record, trace element data have been shown as a proxy for anoxia for the three separate portions of the section previously studied (Bond et al. Reference Bond, Wignall, Joachimski, Sun, Savov, Grasby, Beauchamp and Blomeier2015; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015; Wignall et al. this volume). For reference, the composite curve of Mo normalized to Al is shown through the entire interval (Fig. 3c). Results show relatively low values at the base of the section with a significant spike in Mo/Al at c. –40 m, which coincides with the shift to higher TOC values and minor negative shift in δ13Corg. Above the LPE boundary there is a second spike in Mo/Al that initiates c. 5 m after the main LPE event. This is followed by a gradual decline in Mo/Al until c. 200 m, coincident with the reversal in the trend of carbon isotopes. The Mo/Al values progressively increase again through the next 100 m until +300 m, where peak Mo/Al ratios are coincident with the minimum in δ13Corg values. Mo/Al values then become highly variable for the rest of the measured section.

4.d. Mercury

Hg values for the studied section, reported here for the first time, are plotted in Figure 3d. Hg values are 0.005–0.010 μg g–1 in the basal 60 m of section and then show a shift above –40 m to values up to 0.050 μg g–1, followed by a subsequent decline to values of c. 0.020 μg g–1 in the 10 m just below the LPE boundary. At the LPE there is a significant spike in Hg to the highest values observed in the section (>0.130 μg g–1). Hg concentrations drop rapidly to background values of 0.005–0.010 μg g–1 through the remainder of the section. The only exception is a brief spike at c. +300 m, where Hg concentrations up to 0.065 μg g–1 are observed.

In both marine and freshwater environments, dissolved Hg has been shown to have a strong affinity for organic matter (OM) (Mason, Reinfelder & Morel, Reference Mason, Reinfelder and Morel1996; Gagnon, Pelletier & Mucci, Reference Gagnon, Pelletier and Mucci1997; Benoit et al. Reference Benoit, Mason, Gilmour and Aiken2001; Han et al. Reference Han, Gill, Lehman and Choe2006; Gehrke, Blum & Meyers, Reference Gehrke, Blum and Meyers2009). Grasby et al. (Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b) have also shown that OM strongly controls Hg sequestration over geological time. Along with absolute concentrations, the Hg/TOC ratio is plotted in Figure 3e. However, TOC values are too low to be considered accurate for parts of the section, where Rock-Eval analyses cannot accurately resolve concentrations <0.2% TOC; as a result, only samples with TOC >0.2% are plotted as lower accuracy can greatly affect the calculated ratio. These data show a general trend where the Hg/TOC ratio has constant low values through the section. The exceptions to this are the large spikes in Hg/TOC values that occur at the LPE boundary as well as smaller shifts that occur at –40 m as well as at c. +300 m. These increases in Hg/TOC ratio are consistent with zones where there are large spikes in absolute Hg concentration. Hg values are low outside these three levels.

5. Discussion

5.a. Carbon isotope chemostratigraphy

The δ13C record through sediments of Permian – Early Triassic age shows significant shifts that are comparable to those observed in the Sverdrup Basin (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 a) as well as with inorganic δ13C trends from records in the Panthalassa (Horacek, Koike & Richoz, Reference Horacek, Koike and Richoz2009) and the Tethys (Payne et al. Reference Payne, Lehrmann, Wei, Orchard, Schrag and Knoll2004; Horacek, Brandner & Abart, Reference Horacek, Brandner and Abart2007). This demonstrates that Festningen records global variation in biogeochemical cycles through this time interval. These can be used as a chemostratigraphic tool to support both regional and global correlation.

Bond et al. (Reference Bond, Wignall, Joachimski, Sun, Savov, Grasby, Beauchamp and Blomeier2015) argued that the minor negative carbon anomaly at –40 m correlates with the Capitanian Crisis. The LPE event, as marked by the loss of chert forming siliceous sponges, is characterized by the onset of a large negative shift in δ13Corg that reaches a minimum in the basal Vardebukta Formation (Wignall, Morante & Newton, Reference Wignall, Morante and Newton1998; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Bond, Wignall, Talavera, Galloway, Piepjohn, Reinhardt and Blomeier2015). Above the Kapp Starostin Formation, Wignall et al. (this volume) show that the next negative low point at c. 300 m is correlative with the end-Smithian Substage. This is also consistent with comparison to the δ13Corg record from the Smithian stratotype (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 a), as illustrated in Figure 4. This makes the low in carbon isotope values equivalent to the Smithian/Spathian Extinction event that was associated with renewed Siberian Trap volcanism and rapid global temperature increase (Brayard et al. Reference Brayard, Bucher, Escarguel, Fluteau, Bourquin and Galfetti2006; Orchard, Reference Orchard2007; Xie et al. Reference Xie, Pancost, Wang, Yang, Wignall, Luo, Jia and Chen2010; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Joachimski, Wignall, Yan, Chen, Jiang, Wang and Lai2012).

Figure 4. Correlation of carbon isotope and Hg records from the Smithian stratotype (left side; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 a) with record from Festningen (right side; this study).

5.b. Mercury deposition

The Hg record at Festningen shows a relatively constant background value through the majority of the succession analysed (<0.020 μg g–1). However, notable spikes in Hg concentration occur coincident with the three extinction levels represented in this section (Capitanian Crisis, LPE and Smithian/Spathian Extinction). Of these three spikes the most significant occurs at the LPE boundary. Aside from the three most prominent Hg spikes, there is also a slight increase in the upper Dienerian portion of the section. It is interesting to note that these prominent Hg spikes are all associated with shifts to lower δ13C values. In addition, there is a general association of higher Hg concentrations associated with high Mo/Al values (Fig. 2). While this may suggest increased Hg sequestration associated with changes to more anoxic environments, a plot of Mo/Al versus Hg reveals that there is no correlation (Fig. 5). Despite the general relationship, the data suggest that anoxia has no direct influence on Hg sequestration in sediments.

Figure 5. Plot of the Mo/Al ratio versus Hg concentration.

Given the low organic matter content throughout much of the Lower Triassic portion of the studied section, reliable Hg/TOC ratios are not always possible to obtain. For values <0.2% TOC, inaccuracies in measurement can lead to magnified errors and highly variable Hg/TOC values that are not reflective of natural conditions; these are therefore not shown here. However, for TOC values >0.2%, the Hg/TOC ratios for the Festningen section have relatively constant background values (vertical dashed line in Fig. 3e). These results are consistent with Hg/TOC through the Lower Triassic Smithian stratotype, Sverdrup Basin (Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b), indicating a general background level of Hg sequestration into sediment that is largely controlled by organic matter deposition.

The notable exceptions to this background Hg deposition are spikes in both total Hg concentrations as well as Hg/TOC levels at the three extinction levels (Fig. 3). Previously Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp (Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012) and Grasby et al. (Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b) argued that Hg anomalies in the geological record are related to massive Hg emissions associated with periods of major volcanic eruptions. Our results from Festningen provide support for this hypothesis, showing that over the c. 12 Ma record there are three prominent Hg anomalies superimposed on background Hg concentrations. In each case these Hg spikes are associated with global extinction events that have previously been tied to LIP eruptions: Capitanian Crisis (Emeishan eruptions); LPE (Siberian Traps); and Smithian/Spathian Extinction (renewed Siberian Traps) (Paton et al. Reference Paton, Ivanov, Fiorentini, McNaughton, Mudrovska, Reznitskii and Demonterova2010; Xie et al. Reference Xie, Pancost, Wang, Yang, Wignall, Luo, Jia and Chen2010; Bond & Wignall, Reference Bond, Wignall, Keller and Kerr2014).

On a regional perspective the Hg spikes observed at Festningen closely correspond to those in the Sverdrup Basin (Fig. 4). This indicates that these periods of anomalous Hg deposition are regional in scope, and suggests periods of enhanced Hg deposition over broad areas.

6. Conclusions

The organic carbon isotope records from the Festningen section show trends through sediments of late Permian – Early Triassic age that closely correspond to those of the Sverdrup Basin, as well as the global inorganic carbon record. These results illustrate that NW Pangea records perturbations to the global carbon cycle. It was previously demonstrated that Hg is an excellent proxy for periods of major volcanic activity in the geological record (Sanei, Grasby & Beauchamp, Reference Sanei, Grasby and Beauchamp2012; Grasby et al. Reference Grasby, Beauchamp, Embry and Sanei2013 b; Sial et al. Reference Sial, Lacerda, Ferreira, Frei, Marquillas, Barbosa, Gaucher, Windmöller and Pereira2013). The Festningen section records a general constant background of Hg deposition through time. However, there are notable spikes in Hg concentration as well as in the Hg/TOC ratio that correspond to periods of mass extinction (Capitanian Crisis, the LPE event and the Smithian/Spathian Extinction), all of which have been associated with LIP events. Our results therefore support the use of Hg as a marker for LIP eruptions. What remains uncertain is what role such Hg release could have on ecosystems. Hg is certainly one of the most toxic elements for life, and enhanced Hg flux from large igneous events would likely have a global impact on both the terrestrial and marine realm. Our results show that there are consistent records of Hg spikes associated with LIP events and mass extinctions across NW Pangea. The global nature of these records remains to be demonstrated. If they are more widely distributed, then Hg release could have played a role as a significant extinction mechanism throughout Earth's history.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible by Karsten Piepjohn of Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaftern und Rohstoffe, Geozentrum. M. Parson assisted with Hg analyses and R. Stewart with Rock-Eval analyses. DB acknowledges financial support from NERC Advanced Fellowship grant NE/J01799X/1 and the Research Executive Agency for Marie Curie IEF grant FP7-PEOPLE-2011-IEF-300455. PW acknowledges support from NERC grant NE/I015817/1.