Psychotic disorders in adolescence have widespread effects on functioning and are often associated with premorbid vulnerabilities (Reference HollisHollis, 2003), behavioural problems, specific learning difficulties (Reference Nicolson, Lenane and SingaracharluNicolson et al, 2000; Reference RemschmidtRemschmidt, 2001) and substance misuse (Reference Hambrecht and HafnerHambrecht & Hafner, 2000). Individual development may be severely affected, with long-term implications for social inclusion and personal and economic independence. Studies of adults with psychosis indicate that assertive multi-disciplinary intervention early in the course of illness may improve outcome (Reference Birchwood, Fowler and JacksonBirchwood et al, 2000). Current policy recommends action against social exclusion and the introduction of early intervention teams for people with psychosis aged 14–35 years (Department of Health, 2000; Clinical Standards Board for Scotland, 2001; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002; Social Exclusion Unit, 2004). We report here for the first time cross-sectional clinical and social outcomes and service provision for a representative group with adolescent-onset psychosis who have received their care from mainstream mental health services. The participants included people who were no longer in touch with mental health services. Information such as this is essential to guide the planning of developmentally appropriate services.

METHOD

The study received approval from the multicentre and local research ethics committees, the Information and Statistics Division of National Health Service (NHS) Scotland and local healthcare managers.

Study area and population

The investigation was carried out in the socio-economically diverse areas of Edinburgh, the Lothians, Lanarkshire and south Glasgow, covering a population in 2001 of 1 750 000, about a third of the population of Scotland. Approximately 200 000 adolescents were at risk of having psychosis during the study period 1 September 1998 to 31 August 2001 (Reference ComptonCompton, 2001). Young people were eligible if at any time prior to their 18th birthday they had been in contact with mental health services for a psychotic illness, including those who had subsequently lost contact with services. Those with an ICD–10 diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, and all psychosis subgroups from mood disorders and disorders due to psychoactive substance misuse were included (World Health Organization, 1992). Those with psychosis of organic aetiology were excluded, as were those with comorbid learning disability, because many of the instruments had not been validated in this population.

Identification of participants

Potential candidates for the study were identified from three separate sources: routinely collected admission and discharge data from the Information and Statistics Division of the Scottish Executive; local hospital case registers; and clinicians in child and adolescent and adult mental health services. Any suggestion of psychosis led to further consideration for inclusion. Case records were examined by one of two clinical researchers, each of whom had several years’ experience working with young people with psychosis, and ICD–10 diagnoses based on case-note review were generated using the Operational Criteria Checklist (OPCRIT; Reference Craddock, Asherson and OwenCraddock et al, 1996), a valid and reliable research instrument that offers an efficient alternative to more lengthy diagnostic procedures. Interrater reliability ratings for this study were very good across 18 sets of case notes (κ=0.83 for diagnostic categories; κ=1.0 for psychosis v. no psychosis). Information relating to first service contacts, socio-demographic factors and substance misuse were also taken from the case notes. In two cases a clear history of psychosis was evident from information provided by the clinician identifying the cases, but access to case notes to allow formal OPCRIT confirmation of this was denied by the responsible medical officers. These two cases were included in the prevalence figure but excluded from subsequent analysis.

Recruitment for interview

Attempts were made to approach all suitable candidates for interview unless vetoed by key healthcare professionals. Ethical permission was obtained for an opt-out research design as a low response rate was anticipated. This allowed the research team to approach the young people directly (by letter, telephone or home visit) to ascertain whether they wished to take part in the study if no reply to the initial contact letter had been received within 2 weeks. Interviews were conducted by either of the two researchers, except in the few cases where there were safety concerns. Eight joint interviews were performed for the purposes of calculating interrater reliability (κ>0.7 for clinical rating scales, with one exception: for anxiety, κ=0.5). The ratings of cardinal problems and needs were made by the primary researcher (L.B.) with consensus decisions with V.M. and A.P. in several cases where there was uncertainty.

Interview procedure

The Cardinal Needs Schedule (Reference Marshall, Hogg and LockwoodMarshall et al, 1995), a modified version of the Medical Research Council Needs Assessment Schedule, was specifically adapted for this study. This enabled a detailed age-appropriate assessment of current disability and need in adolescents with psychotic illnesses using interview information from participants, their carers and keyworkers. Keyworkers were the professionals currently most closely involved in the provision of care for the participant, or the most recently involved professional if the young person was no longer in contact with services. The validated research outcome measures listed below were incorporated in the schedule to determine whether problems were present in 11 clinical and 10 social domains of functioning (see Table 4):

-

(a) Manchester Scale (Reference Krawiecka, Goldberg and VaughanKrawiecka et al, 1977): this is a 14-item research clinician-rated scale measuring psychosis (hallucinations, delusions, incoherence of thought), depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation during the past week. Ratings of moderate to severe are considered pathological. In addition, side-effects (modified to include profiles of the newer antipsychotics) are rated as not present, mild (very little/little) or marked (quite a lot/very much).

-

(b) Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (Reference Altman, Hedeker and PetersonAltman et al, 1997): a five-item self-report scale (scored 0–4) rating manic symptoms during the past week. A total score of 6 or more is indicative of mania.

-

(c) Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (Reference AndreasenAndreasen, 1989): this scale consists of five sub-scales comprising 24 items rated by carer and observation at interview, for negative symptoms during the past month. Higher scores indicate greater deficit.

-

(d) Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (Reference Wistedt, Rasmussen and PedersenWistedt et al, 1990): an 11-item carer- or keyworker-rated scale for behaviour during the past month. An item scored ‘moderate’ or above indicates an episode of aggression.

-

(e) Drake Substance Misuse Scales (Reference Drake, Osher and NoordsyDrake et al, 1990): five-point scale rated from all sources for alcohol and illicit drug use during the past 6 months. Ratings of misuse and dependence indicate difficulties.

-

(f) Goodyer Friendship Questionnaire (Reference Meltzer, Gatard and GoodmanMeltzer et al, 2000): a seven-item self-report scale for friendships during the past month. Total scores 0–2 indicate severe lack of friendships; 3–4, moderate lack; 5 or over, little or no lack.

-

(g) General Functioning Scale – Family Assessment Device (Reference Byles, Byrne and BoyleByles et al, 1988): a 12-item scale rated separately by participants and carers for family functioning during the past month. Cumulative scores of 2.00 or over indicate unhealthy family functioning.

According to domain-specific criteria, an assessment was made as to whether an ‘objective problem’ was present. These became ‘cardinal problems’ (a problem requiring action) if one or more of the following criteria were met:

-

(a) the patient is willing to accept help for the problem (the cooperation criterion);

-

(b) people caring for the patient are experiencing considerable anxiety, annoyance or inconvenience as a result of the problem (the carer stress criterion);

-

(c) the nature and severity of the problem are such that the health or safety of the patient or others is at risk (the severity criterion).

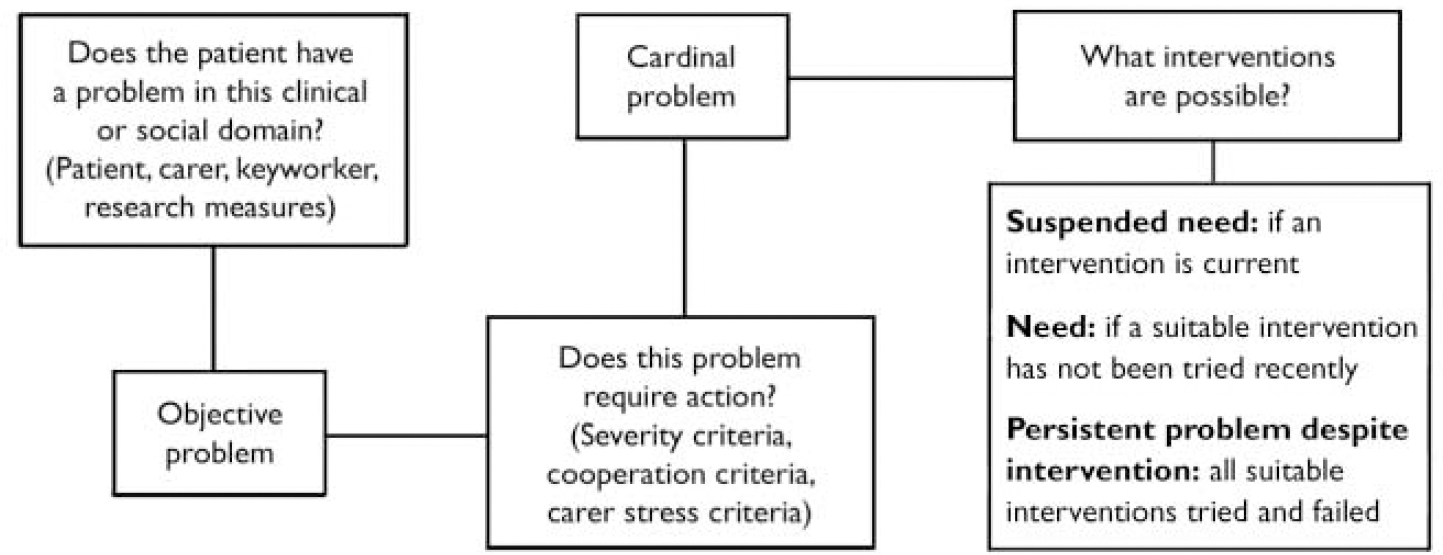

Criteria for deciding on the presence or absence of a cardinal problem are not applied uniformly for each domain of functioning. For example, people who could not use community facilities such as shops or public transport would not have a cardinal problem in this area if they did not want help. On the other hand, dangerous or destructive behaviour becomes a cardinal problem on the basis of severity, so that people who are behaving dangerously should receive an intervention even if they would not choose it. Each cardinal problem is examined with respect to the interventions that have already been offered and the current circumstances of the individual young person (Fig. 1). The cardinal problem is then rated as one of the following:

Fig. 1 Cardinal Needs Schedule protocol for establishing needs (Reference Murray, Walker and MitchellMurray et al, 1996), with permission of the BMJ Publishing Group.

-

(a) a suspended need (a cardinal problem that is currently being addressed by appropriate interventions);

-

(b) a persistent problem despite interventions (all appropriate interventions have been tried but the cardinal problem persists);

-

(c) a need (a suitable intervention exists but has not been given a recent adequate trial).

The Global Assessment of Functioning, an integral part of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, was used to supplement information about overall levels of functioning (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

RESULTS

Prevalence and diagnosis

Seventy-four males and 29 females met the inclusion criteria. The 3-year prevalence was 5.9 per 100 000 general population and approximately 50 per 100 000 adolescents at risk. The ICD–10 diagnoses generated with OPCRIT for 101 of the 103 people identified were as follows: schizophrenia 66 (65%), schizoaffective disorder 11 (11%), bipolar disorder with psychotic symptoms 3 (3%), other psychotic disorders 21 (21%). Eleven of the young people were of non-European ethnic origin.

History of mental health problems and service contacts

Details of the onset of psychosis and contact with the mental health services are shown in Table 1 for the 101 people for whom we had access to case notes. Twenty-seven individuals had a history of harmful use of alcohol, and 47 harmful illicit drug use as rated from case notes, including 26 who misused both drugs and alcohol. Since becoming unwell 86 had received in-patient care; only 20% of first admissions were to specialist adolescent facilities. At the time of follow-up 6 of the total group were in secure psychiatric units, 2 were in prison and 14 were detained under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984.

Table 1 Onset of psychosis and contact with mental health services (n=101)

| Mean | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Onset of psychosis and contact with mental health services | ||

| Age at onset of psychosis, years | 16.0 | 10.2-17.9 |

| Age at inclusion in study, years | 18.9 | 13.5-21.6 |

| Time from onset to inclusion in study, years | 2.9 | 0.5-6.8 |

| Time as in-patient (0-8 admissions), days | 84 | 0-1701 |

| Current contact with services | ||

| Age of participants, years | ||

| Child and adolescent services (n=26) | 17.4 | 13.5-19.7 |

| Adult services (n=54) | 19.4 | 16.5-21.6 |

| No contact (n=21) | 19.2 | 15.9-21.3 |

Recruitment for interview

Consent to participate in the interview could not be sought from 25 (24%) of the 103 identified young people for the following reasons: their mental health (n=8) or physical health (n=1) was too poor; the person had left Scotland (n=5); permission to examine case records and to approach the person was denied (n=2); there was exceptional delay in obtaining permission from the general practitioner to approach the young person (n=1); we could not locate the person despite extensive searches including contacting previous social workers or general practitioners and visiting the last known address (n=5); when finally located (name on house door, spoke to other resident in household, etc.) the person could not be met to discuss the study, despite at least five attempts (n=3). Of the remaining 78 young people, 53 gave permission for interview contact. In 44 cases both the young person and the carer were interviewed, in 5 cases only the young person, and in 4 cases only the carer was interviewed. Some additional information was provided by three keyworkers if the young person was an in-patient and there was no carer available. Carers were invariably parents.

There was no statistically significant difference between those from whom consent for interview could not be sought (n=25) and those who were available in regard to type of service currently received (child and adolescent v. adult), current status under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984, gender, ethnicity, substance misuse from case notes, length of follow-up and diagnostic grouping. Those for whom consent could not be sought were significantly more likely to be out of contact with the mental health service (Pearson's χ2=4.96, P=0.04) and have a shorter duration of untreated psychosis (Kruskal–Wallis X=4.29, P=0.04). There was no significant difference between those who gave consent (n=53) and those who did not (n=25) as regards current status under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984, whether currently in contact with the mental health services, type of service currently received, gender, ethnicity, substance misuse, length of follow-up and diagnostic grouping. Those who did consent to interview had a significantly longer duration of untreated psychosis (Kruskal–Wallis X=4.36, P=0.04).

Characteristics

Socio-demographic features of interviewees

Table 2 shows the current socio-demographic circumstances of the participants interviewed (n=53). Thirty-eight (78%) of the 49 participants aged 16 years or over were claiming benefits: disability living allowance (n=23), incapacity benefit (n=12), severe disability allowance (n=3), income support (n=16) and other benefits (n=3).

Table 2 Socio-demographic characteristics of interviewed sample

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Accommodation | |

| Parental home | 38 (72) |

| Supported accommodation | 3 (6) |

| Own tenancy | 5 (9) |

| Medium- or long-term in-patient | 5 (9) |

| Homeless (hostel, sleeping rough, in prison) | 2 (4) |

| Current employment/education/occupation | |

| School | 7 (13) |

| Higher education (college/university) | 10 (19) |

| Unskilled work | 5 (9) |

| Skilled work (part-time) | 1 (2) |

| Mental health day facility | 17 (32) |

| None | 14 (26) |

| No qualification (≥ 16 years, n=49) | 14 (29) |

Clinical features

Clinical findings from the outcome scales are detailed in Table 3. Using the Friendship Questionnaire, 40 (82%) reported a moderate to severe lack of friendships, including 7 who had ‘no friends’. Thirty-five (71%) participants said they were ‘not very happy’ or ‘unhappy’ with their friendships. Twenty-three (43%) had ‘unhealthy’ family functioning (rating >200 on the General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device).

Table 3 Clinical findings in interviewed participants

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Global Assessment of Functioning (n=53) | |

| Minimal—mild impairment (score 61-100) | 15 (28) |

| Moderate impairment (score 51-60) | 9 (17) |

| Serious impairment (score 41-50) | 19 (36) |

| Pervasive impairment (score 1-40) | 10 (19) |

| Manchester Scale rating moderate—severe (n=49) | |

| Psychosis | 16 (33) |

| Depression | 9 (18) |

| Anxiety | 23 (47) |

| Suicidal thoughts | 7 (14) |

| Altman Self-Rating Mania Scale (n=49) | |

| Symptoms of mania (total rating > 6) | 2 (4) |

| Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, Global scale (moderate—severe) (n=50) | |

| Affective flattening | 18 (36) |

| Alogia (impoverished thinking) | 9 (18) |

| Avolition/apathy | 22 (44) |

| Anhedonia/asociality | 19 (38) |

| Attention | 5 (10) |

| Social Dysfunction and Aggression Scale (moderate—severe on ≥ 1 item) (n=48) | |

| Verbal aggression (directed, non-directed) | 6 (13) |

| Physical aggression (to staff, non-staff, things) | 5 (10) |

| Drake Substance Misuse Scales (n=53) | |

| Alcohol only (misuse—dependence) | 4 (7.5) |

| Drugs (misuse—dependence) | 5 (9.4) |

| Both alcohol and substances (misuse—dependence) | 6 (11.3) |

Medication and side-effects

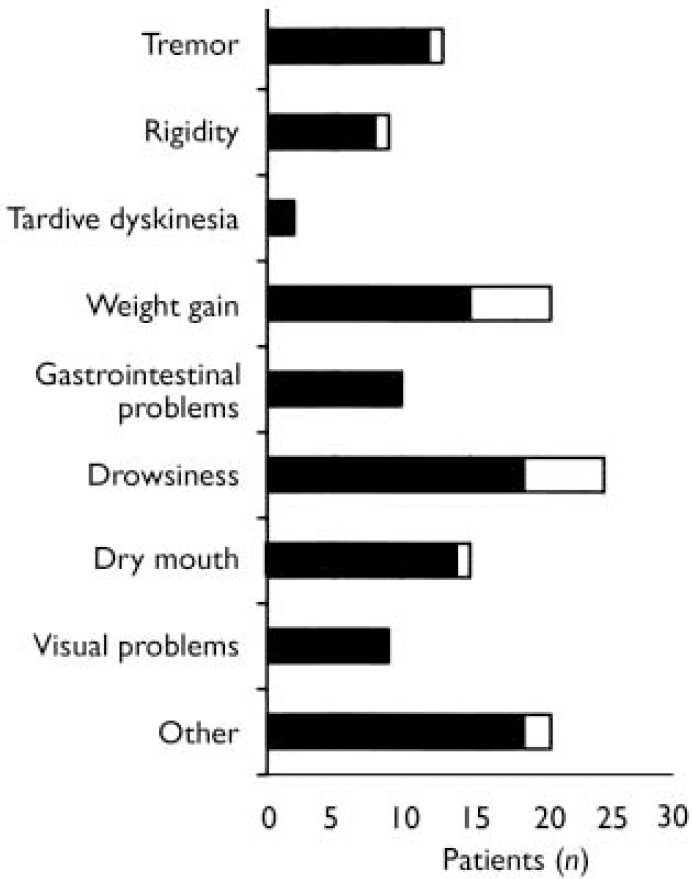

Forty-two (86%) of those interviewed were currently taking medication for their mental health: 32 were taking newer antipsychotics – most commonly olanzapine (n=9), clozapine (n=8), quetiapine (n=5) and risperidone (n=5) – and 10 were taking older antipsychotics, including chlorpromazine (n=5) and depot preparations (n=4). Six participants were taking antidepressants, 10 mood stabilisers and 4 benzodiazepines. Twenty-seven (55%) were taking more than one psychotropic medication, of whom 9 were taking oral medication to counteract side-effects (e.g. procyclidine, hyoscine, thyroxine and lactulose). Thirty-six (86%) of those taking medication reported current drug side-effects; 18 (43%) reported either at least one marked side-effect or more than four mild side-effects. Figure 2 shows the side-effects most commonly experienced.

Fig. 2 Medication side-effects (n=42): □ marked; ▪ mild.

Summary of service provision during the past year

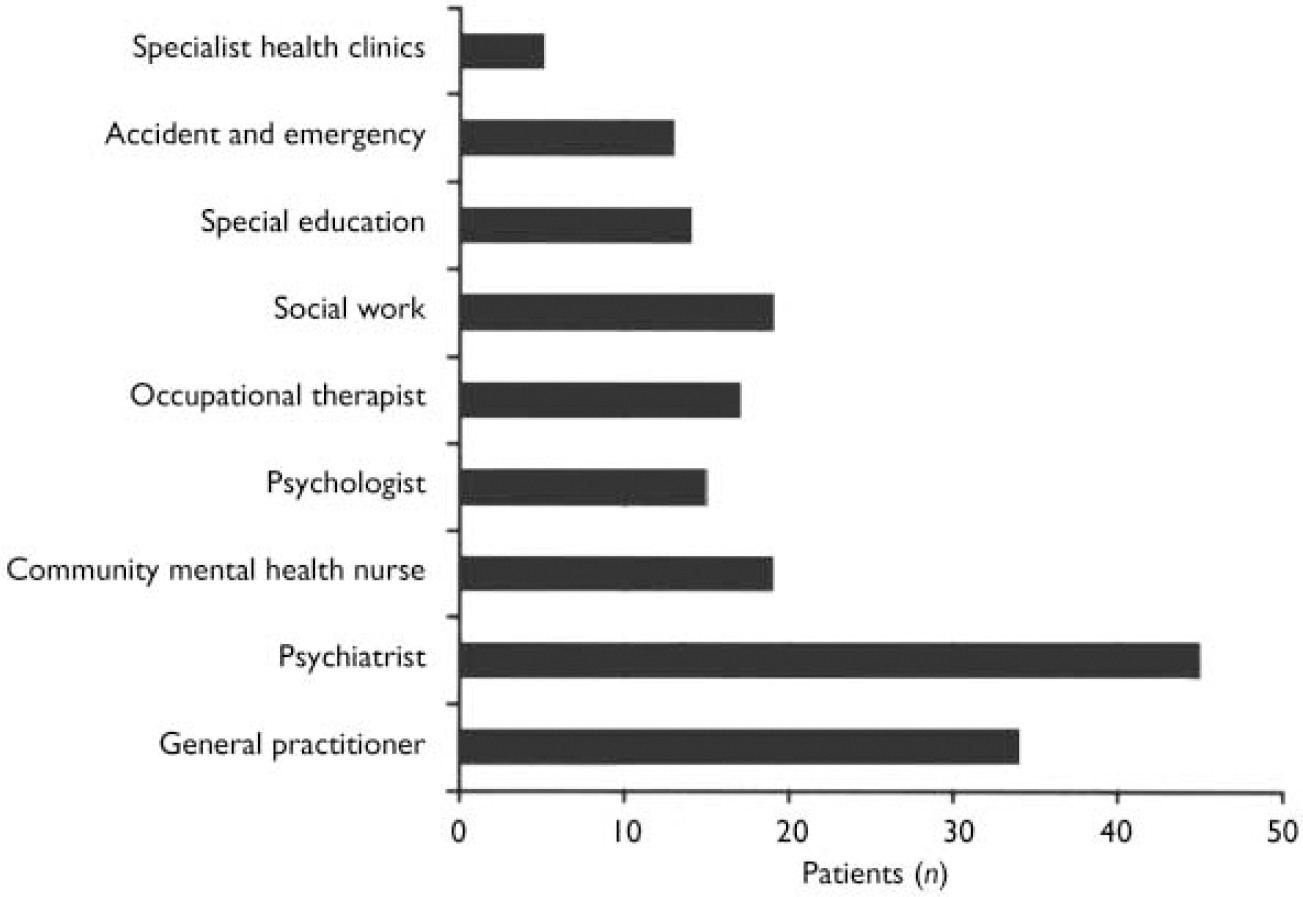

After contact with psychiatric staff, primary care consultations constituted the most frequently attended service during the previous year (Fig. 3). Eighteen participants had consulted their general practice for mental health issues and 16 for physical health concerns. Nineteen had contact with the social work department (mostly for issues relating to their mental health, including assistance with housing and benefits). Thirteen had attended accident and emergency departments (four for their mental health, including treatment of self-harm). Details of unmet need in relation to service provision are set out in Table 4.

Fig. 3 Contact with health services during the past year (n=49).

Table 4 Developmental Needs Schedule: detailed summary of findings (n=53)

| Domain | Objective problem | Cardinal problem | Suspended need | PPDI | Need | Description of intervention required (for young person, unless specified) to fulfil need1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical domain | ||||||

| Psychosis | 18 | 17 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 1 × trial of alternative antipsychotic, psychological therapy |

| 1 × CPN, clinical psychology | ||||||

| Anxiety/mood | 30 | 30 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 1 × clinical psychology, cognitive—behavioural therapy |

| 3 × anxiety management skills training | ||||||

| Side-effects (on medication n=45) | 39 | 39 | 34 | 2 | 3 | 2 × trial of alternative antipsychotic medication |

| 1 × psychiatric assessment | ||||||

| Organic problem | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Physical problem | 13 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 4 × review by suitably qualified specialist or GP |

| Underactivity (negative symptoms) | 23 | 22 | 17 | 0 | 5 | 1 × social stimulation programme |

| 2 × support/coping advice for carer | ||||||

| 1 × support/coping advice for young person | ||||||

| 1 × domiciliary social stimulation programme | ||||||

| Dangerous/destructive behaviour (self/others) | 20 | 19 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 1 × assessment of risk |

| 1 × psychiatric assessment | ||||||

| Socially inappropriate behaviour | 13 | 9 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 × coping advice and skills training |

| 1 × psychiatric assessment | ||||||

| 1 × domicilary coping skills training | ||||||

| Illicit drug use | 17 | 13 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 2 × community supervision |

| 1 × secure placement with detoxification | ||||||

| 1 × coping advice | ||||||

| 2 × education/advice | ||||||

| Alcohol misuse | 10 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 1 × community supervision |

| 2 × coping advice | ||||||

| 2 × education and advice | ||||||

| 1 × secure placement including detoxification | ||||||

| Knowledge of mental health and treatment | 36 | 36 | 17 | 1 | 18 | 8 × psychoeducation for young person and carer |

| 5 × psychoeducation for young person | ||||||

| 5 × psychoeducation for carer | ||||||

| Social domains | ||||||

| Transport/amenities | 23 | 22 | 14 | 0 | 8 | 7 × coping advice |

| 1 × insufficient information to rate | ||||||

| Education attendance (registered in education n=17) | 9 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 × coping advice/support |

| Educational performance | 19 | 9 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 5 × adult education classes |

| Keeping occupied | 40 | 35 | 23 | 1 | 11 | 3 × structured daytime activity |

| 4 × advice regarding leisure activity | ||||||

| 1 × community social activity | ||||||

| 2 × advice regarding accessing work/education | ||||||

| 1 × direct support | ||||||

| Hygiene/dressing | 10 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 1 × need for prompting about personal hygiene |

| Domestic skills (> 16 years living away from home n=11) | 7 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 2 × remedial training |

| 2 × family advice and support | ||||||

| 1 × domiciliary support/coping advice | ||||||

| Family relationships | 34 | 26 | 6 | 4 | 16 | 12 × family assessment |

| 1 × supportive counselling and advice | ||||||

| 3 × regular promotion of coping strategies | ||||||

| Friendships | 32 | 16 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 1 × social skills training |

| 2 × psychiatric day unit | ||||||

| 3 × befriender | ||||||

| Living situation | 22 | 21 | 15 | 1 | 5 | 2 × social work input |

| 3 × home visit by keyworker | ||||||

| Money/own affairs (> 16 years n=49) | 24 | 17 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 2 × advice and support for carers |

| 6 × advice about benefits and budgeting | ||||||

| 2 × direct support |

Needs assessment

Table 4 shows the symptoms and disabilities reflected as objective problems. Every participant had at least two objective problems, with a mean of 8.3 (range 2–18, 95% CI 7.2–9.4). All but three participants had cardinal problems, with a mean of 7.0 per person (range 0–16, 95% CI 5.9–8.1). Cardinal problems were rated according to the interventions offered and circumstances of the young person. The levels of suspended needs (mean 4.5 per person, range 0–13, 95% CI 3.5–5.4) represent the number of cardinal problems appropriately addressed. Six participants also had one persistent problem despite intervention (PPDI), one had two PPDIs, and another two participants had three PPDIs.

Across all the domains the mean number of unmet needs was 2.3 (range 0–8, 95% CI 1.6–2.9); a fifth of participants had five or more unmet needs. Thirty-one per cent had had all their needs met. Within the clinical domains, relatively few unmet needs were observed for psychotic or anxiety/mood symptoms, dangerous/destructive behaviour, socially inappropriate behaviour and side-effects. Four participants had unmet needs in regard to underactivity (reflecting negative symptoms) and physical problems, and six had unmet needs for illicit drug use and alcohol misuse. However, psychoeducational needs (knowledge about mental health and treatment issues) were unmet for 18 (33%) participants. In comparison, needs associated with social domains were quite frequently unmet: for supporting family relationships (n=16), keeping occupied (n=11) and managing money/own affairs (n=10).

DISCUSSION

This study describes in detail for the first time the disabilities, needs and service provision for a representative group of young people with early-onset psychosis presenting to mainstream mental health services (Reference Rabinowitz, Bromet and DavidsonRabinowitz et al, 2003). Those detained under the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984 and representatives of all diagnostic subgroups of psychosis, including substance misuse, were included. Previous studies have found high levels of disability especially in those with schizophrenia (Reference HollisHollis, 2000). Even within this diagnostically heterogeneous group we found persistent difficulties with symptoms and social functioning, with over half of the young people showing serious to pervasive levels of impairment on the Global Assessment of Functioning despite the early stage of their illness. Friends have a crucial role in supporting teenagers with mental health problems (Mental Health Foundation, 2001). Eighty-two per cent of our sample described difficulties with friendships compared with 6% in a non-clinical sample aged 11–15 years rated using the Friendship Questionnaire (Reference Meltzer, Gatard and GoodmanMeltzer et al, 2000).

Prevalence

We studied a third of the total population of Scotland, who received services from different NHS trusts, education and social work departments. The 3-year prevalence of early-onset psychosis of approximately 50 per 100 000 of the at-risk population indicates a rare disorder, with only a small number of cases occurring in each local area. Differences in methodology and inclusion criteria make comparison with other studies problematic; however, Gillberg et al (Reference Gillberg, Wahlstrom and Forsman1986) found a mean yearly prevalence for 13- to 19-year-olds hospitalised with psychosis of 7.7 per 10 000. In a Scottish sample in the 1980s the annual incidence of schizophrenia in the age-group 15–19 years was found to be 1.0 in males and 0.5 in females per 10 000 (Reference Takei, Lewis and ShamTakei et al, 1996).

Needs assessment

Using a modified version of the Cardinal Needs Schedule we were able to make a detailed and age-appropriate assessment of patients’ problems and the work being done to address these. Possible interventions were selected from the evidence base and good practice guidelines for care (Department of Health, 2000; American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2001; Clinical Standards Board for Scotland, 2001) rather than from the services available in each local area. High levels of suspended needs represent considerable levels of appropriate input, and effective interventions may mean that previous difficulties are no longer rated as current problems; underrecording of the services provided is therefore inevitable. However, for a minority of the sample we found serious failures of care, with unmet need identified in several domains. There was greater unmet need in regard to psychological and social components of disability compared with ‘medical’ aspects. Murray et al (Reference Murray, Walker and Mitchell1996) found similar results using the Cardinal Needs Schedule in a community prevalence study of people aged 18–65 years with psychosis, as did Macpherson et al (Reference Macpherson, Varah and Summerfield2003) in a similar adult sample assessed using the Camberwell Assessment of Needs Short Appraisal Schedule. This is in spite of the well-established contribution of psychoeducation and psychological treatment methods (Reference Birchwood, Fowler and JacksonBirchwood et al, 2000; American Association of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2001) and government recommendations regarding access to employment and education for those with disability (Department of Health, 2000; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002; Special Educational Needs and Disability Act 2001; Great Britain Parliament House of Commons Work and Pensions Committee, 2003). We found high levels of difficulties with family functioning: 43% v. 19% in a non-clinical population measured using the General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device (Reference Byles, Byrne and BoyleByles et al, 1988). It is disappointing therefore to note the particularly high levels of unmet need in the domain of family relationships, given the relatively robust evidence base for family interventions early in the course of psychotic illnesses (Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al, 2002). Also, many young people and their carers and keyworkers described frustration at the lack of resources for keeping young people with severe mental illness occupied during the day.

Access to in-patient care

This study has confirmed the widely held clinical impression that there is an important gap in adolescent in-patient care provision; 80% of first admissions were to adult wards, almost identical to the Swedish levels of 83% in the 1970s (Reference Gillberg, Wahlstrom and ForsmanGillberg et al, 1986). Although methodological differences make direct comparison problematic, it is noteworthy that the National In-patient Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Study (Reference O'Herlihy, Worrall and BanerjeeO'Herlihy et al, 2001) found that 4.6 per 100 000 persons aged 18 years and under from all diagnostic groups were admitted to adult general psychiatry wards in England and Wales; the most common reasons for such admissions were non-availability of an appropriate facility or the appropriate facility either being full or not accepting the patient. Adult psychiatric units are unacceptable for the care of young adolescents, their admittance to such units being at odds with good practice (Department of Health, 1998; Mental Welfare Commission for Scotland, 2001; Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003) and involving risks to health and safety because of current staffing levels and patient mix (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1999). Transitional arrangements between age-demarcated services are required to provide age-appropriate care.

Medication and side-effects

Although most young people in our sample were being treated with newer antipsychotics in accordance with treatment guidelines, there were high levels of side-effects. This supports the importance of baseline assessments prior to initiating treatment and further study to refine the use of antipsychotic medications in children and adolescents (Reference Bryden, Carrey and KutcherBryden et al, 2001).

Recruitment and engagement

The response rate of 53% makes these results tentative; however, the opt-out research design allowed inclusion of some participants no longer in contact with the mental health services and those who were more difficult to engage, making the findings more representative of a complete clinical sample. The difficulties experienced in recruitment for the interview phase of the study, despite the active role of interagency workers known to the young people concerned, give a valuable insight into the need for assertive follow-up focusing on working alliances with service users and their families (Reference RoseRose, 2001). This is resource-intensive but must be sustained in spite of competing demands to assist large numbers of patients with less severe conditions (Reference Murray, Walker and MitchellMurray et al, 1996). A prospective study of an incidence sample, although expensive, would provide valuable information on the continuity and disruption of service provision.

Implications of the study

Our findings set challenges for both service planners and providers who have responsibility for the professional care for this vulnerable group. This study shows that the reality of community care for many young people with psychotic illnesses falls short of guidelines for standards of provision (Department of Health, 1998, 2000; Clinical Standards Board for Scotland, 2001; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002; Social Exclusion Unit, 2004). There is also substantial underprovision of adequate in-patient facilities for this group of patients, including secure beds. Routine systematic needs assessment would inform service planning and assist with individual care plans. The low prevalence and complexity of needs support recommendations for a national planning framework integrating care across primary care, child and adolescent and adult mental health services, social work, education and the voluntary sector.

Acknowledgements

We thank the service users, clinicians and administrative staff who supported the study; Ann Maguire and Hester McQueen for their assistance with the identification of participants, work on the adaptation of the Cardinal Needs Schedule and data collection; the Project Steering Group consisting of Andrew Gumley, Fiona Laing, Janette Gardner and Donald Morris; Christopher Gillberg, Peter Craig, Janet Hanley, Dave Will, Ian Goodyer, Howard Meltzer, Janette Henderson and Margaret Van Beck; the Edinburgh branch of the National Schizophrenia Fellowship, the Edinburgh Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility and The Health Foundation London. V.M. was supported by the John, Alfred, Margaret and Stewart Sim Fellowship. The study was funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Executive.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.