1. Introduction

Spain has become a locus for international immigration in recent decades, with approximately 40% of the foreign-born population coming from Latin America (Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigración, 2009). As a result of the large influx of Hispanic immigrants to urban areas, in particular, Latin American immigrants represent more than 10% of the population in major Spanish cities like Madrid, Barcelona, and Valencia (Gratius, Reference Gratius2005). As Spaniards interact with these new, Spanish-speaking members of their community, they likely use multiple cues to make immediate assessments about their interlocutors.

Previous studies have found that different varieties of Spanish, for example, evoke specific stereotypes about their speakers, with Peninsular varieties more strongly associated with family wealth, earning potential, and white-collar jobs than Latin American varieties (Carter & Callesano, Reference Carter and Callesano2018). However, listener perceptions can also be primed by visual or social information, such as whether a speaker looks Hispanic or non-Hispanic (Gutiérrez & Amengual, Reference Gutiérrez and Amengual2016) or the belief that a speaker is from a particular country (Carter & Callesano, Reference Carter and Callesano2018). The present study explores how two symbolic boundaries—raceFootnote 1 and accent—intersect, with the goal of determining how Latin American immigrants are perceived by Spaniards in Murcia. We aim to uncover whether the use of different varieties of Spanish indexes differences in national origin, socioeconomic status, and solidarity traits among native Spaniards and how this indexical process interacts with perceptions of racial differences.

To this end, we conducted a perception experiment in which participants were asked to evaluate three speakers of three varieties of Spanish (Spanish, Colombian, and Argentinian) on a series of social properties. A picture showing either a White or a Mestizo face was paired with the aforementioned stimuli on each page of the experiment. The methodological details of the experiment and analysis are provided in Section 3, and, in Section 4, we explain the results of our statistical analysis. Section 5 discusses the broader theoretical impact of the study, and concluding remarks are offered in Section 6. First, we review the recent literature to set the stage for our experiment, detailing perceptions of immigrants in Spain, attitudes toward different varieties of Spanish, and the relevant research on visual cues and speech perception.

2. Background

2.1 Latin American immigration to Spain

Europe has historically been characterized by high rates of emigration. For example, approximately fifty million Europeans moved to North America, Australia, or South America between 1815 and 1930 (Ferenczi & Willcox, Reference Ferenczi and Willcox1929:230–31), but immigration gradually began to outpace emigration in Europe following World War II. The continent is now a popular destination for immigrants, and in 2016 minority immigrant groups accounted for 20.1 million people in Europe, or roughly 4.1% of the total population (EUROSTAT 2017, as cited in Panno [Reference Panno2018]). While different motivations prompt immigration in Europe, it is, in addition to economic opportunities, increasingly motivated by threat evasion, with migrants fleeing civil violence and the impacts of climate change (Donato & Massey, Reference Donato and Massey2016).

This broad tendency toward higher rates of immigration in Europe is also true of Spain. Recent decades have seen an upsurge of international immigration to the country, with newcomers arriving from all over the globe, including Africa, Eastern Europe, Asia, and Latin America (Cachón Rodríguez, Reference Cachón Rodríguez2003; Portes, Vickstrom, & Aparicio, Reference Portes, Vickstrom and Aparicio2011). In the context of Latin American immigration, a shift has taken place in recent decades. According to Connor and Massey (Reference Connor and Massey2010), the United States was the overwhelming destination of twentieth century out-migration from Latin America, but Spain has become a particularly popular destination since joining the European Union in 1986. Compared to the United States, Spain is geographically more distant but culturally more proximal, with lower cultural and linguistic integration costs for newcomers from Latin America. While those geographically closer to the United States (i.e., Mexicans and Central Americans) are more likely to move northward, those geographically more distant from the United States (i.e., South Americans) are more likely to opt for the cultural proximity of Spain when emigrating.

In addition to cultural similarities, Spain’s less restrictive immigration policies and bilateral labor agreements with Latin American countries (i.e., with Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Ecuador in 2001 and with Peru in 2004), prompted by the abundance of foreigners in the workforce and the low fertility rate in Spain, likely contributed to increased Latin American immigration (Gratius, Reference Gratius2005). Even after immigration laws were strengthened in 2000 to align with European Union policies, several amnesty policies were approved to grant residency to undocumented immigrants a posteriori, and, unlike the practices common in the United States, the deportation of undocumented immigrants from Spain is rare.

Finally, Latin Americans enjoy a privileged immigration status in Spain, which likely enhances the desirability of the country as a destination. As Gratius (Reference Gratius2005) explains, most immigrants must live in Spain for ten years before applying for a five-year residency visa (and later, an indefinite visa), but Latin Americans are able to apply after only two years of residency in Spain. Spain’s kinship policies also benefit Latin Americans, especially Latin Americans from specific countries like Argentina, Cuba, and Uruguay. Those who are able to demonstrate that they are the children or grandchildren of a Spaniard obtain Spanish citizenship after one year of permanent residency in the country.

When compared to immigrants from other Latin American countries, Argentines possess an even more privileged social status. Given that approximately 1.5 million Spaniards immigrated to Argentina through the 1970s, the majority of Argentines qualify for the citizenship kinship criterion described above. The earlier migratory waves between the two countries and the resulting family relationships that exist between Argentines and Spaniards have also created close social and cultural bonds. Argentines enjoy a strong media presence in Spain and sympathetic portrayal in the press when compared to other Latin American immigrant groups (García, Reference García2006; Retis, Reference Retis2004). Furthermore, because the majority of Argentinian migrants fleeing political persecution in the 70s and 80s were highly educated, they tended to occupy a similar professional space as Spaniards (Vicente, Reference Vicente Torrado2006:9), whereas more recent migrants from other Latin American countries are more likely to work in unskilled jobs, in large part due to current restrictions in access to the Spanish job market (Bekenstein, Reference Bekenstein2009; García Ballesteros, Giménez Basco and Redondo González, Reference García Ballesteros, Jiménez Basco and Redondo González2009; Vicente Torrado, Reference Vicente Torrado2006). In sum, although Latin Americans have a privileged immigration status in Spain, Argentines occupy an especially privileged position historically, socially, culturally, and professionally.

2.2. Symbolic boundaries in Spain

In any context of large-scale immigration, the established majority group tends to identify symbolic boundaries, or “conceptual distinctions made by social actors… [that] separate people into groups and generate feelings of similarity and group membership” (Lamont & Molnár, Reference Lamont and Molnár2002:168) to differentiate itself from the newcomers. Commonly cited symbolic boundaries include religion, race, language, and citizenship as points of divergence, but the specific symbolic boundaries constructed are dependent on the history of the immigrant group and the societies that receive them (Alba, Reference Alba2005).

Creating symbolic boundaries between Spaniards, on the one hand, and immigrants, on the other, is a sociologically complex distinction, as “…social identities are not only multidimensional but also highly mutable” (Bail, Reference Bail2008:37). To account for the cross-national variation in constructions of symbolic boundaries, Bail (Reference Bail2008) proposed a typology of symbolic boundary configurations in Europe, with Spain falling into a fuzzy set with Portugal, Italy, and other peripheral European countries; this set of countries was characterized by stronger racial and religious symbolic boundaries and weaker cultural and linguistic symbolic boundaries than other European countries. In addition to the complex configurations of symbolic boundaries across receiving societies, the boundaries themselves are often flexible and permeable. Alba (Reference Alba2005) distinguished between “bright” boundaries, which involve an unambiguous difference, and “blurry” boundaries, or more ambiguous or indeterminate distinctions. The social construction of these categories results in real-world consequences, considering that “…the nature of the boundary affects fundamentally the processes by which individuals gain access to the opportunities afforded the majority” (Reference Alba2005:22).

At first blush, language may seem to be a bright boundary between immigrant and majority groups, but several factors make the division blurrier. First, immigrants generally learn, to differing degrees, the majority culture’s language, and their children are often bilingual in both the family language and the majority culture language. Additionally, the linguistic landscape of larger cities, like Los Angeles, tends to be multilingual to some extent, creating a degree of representation of the immigrant language in the majority culture (see Carr, Reference Carr2017). Finally, majority language speakers frequently study the minority language (e.g., Spanish is widely studied by English-speaking American high school and college students), making the language-based boundary more permeable than other boundaries like religion (Alba, Reference Alba2005).

The language category is further complicated by the linguistic legacy of colonization. While many immigrants bring linguistic backgrounds markedly different from those of their new countries (see, for example, Peach & Glebe, Reference Peach and Glebe1995), the vast majority of Latin American immigrants already speak Spanish. In this case, variety of Spanish may serve as the language-based symbolic boundary, although this boundary may also be blurred, as many transplants converge, to some extent, to the receiving society’s dialect (e.g., Dodsworth, Reference Dodsworth2017), and the second generation acquires the majority variety rather than the parents’ variety (e.g., Chambers, Reference Chambers2002; Dodsworth, Reference Dodsworth2017).

Similarly, although cultural and religious differences have been highlighted as a source of tension between Spaniards and immigrants (Aparicio, Reference Aparicio2007; Morales et al., Reference Morales, Anduiza, Rodriguez and San Martin2008), Latin American immigrants share a majority religion and some cultural practices with Spaniards, additional vestiges of colonization. When compared with Latin American immigration in the United States, for instance, the issues and costs of integration are relatively low due to the cultural, linguistic, and religious similarities (Gratius, Reference Gratius2005). While practices differ across these contexts, both Latin Americans and Spaniards may again expect to find themselves on the same side of the religious symbolic boundary and, in certain areas, on the same side of the cultural boundary.

Racial differences have often been downplayed or denied as a source of anti-immigrant sentiment in Spain (Molina Luque, Reference Molina Luque1994). However, when asked to self-report about the discrimination they experienced, immigrants believe nationality and race to be the two most important ethnic boundaries driving discrimination in Spain (Flores, Reference Flores2015). There also seems to be an inverse relationship between reports of nationality-based and racially-based discrimination for non-White immigrants, such that newer arrivals report more mistreatment based on their country of origin and more acculturated immigrants experience more mistreatment based on race. However, when European and Southern Cone immigrants acculturate, they report little racial discrimination, which suggests that whiteness facilitates cultural integration in Spain.

2.3. Attitudes toward different varieties of Spanish

In spite of the linguistic similarities between Spaniards and Latin American immigrants, the vast majority of Spaniards can and do distinguish among different dialects of Spanish (Luijpen, Reference Luijpen2012). In a survey of 79 Spaniards residing in Madrid, Liujpen (Reference Luijpen2012) found that the respondents prefer their own variety of Spanish over others. Within the Latin American context, respondents demonstrate a preference for Argentinian Spanish, associating it with more positive qualities than Ecuadorian or Colombian Spanish. In their metalinguistic commentary, the participants claim to find Argentinian Spanish “prettier,” “more musical,” and “funny,” but these evaluations are likely grounded in the socioeconomic position and reputation of the variety’s speakers in Spain. Argentinian Spanish speakers seem to benefit in terms of social evaluations because of their social contacts with Spaniards and employment, but also in large part because of their strong cultural, linguistic, and media presence. While Argentines appear to be exempt from Spanish fears of immigration, Spaniards seem to associate non-Argentinian Latin American voices with immigration, poverty, and indigenousness.

Some of these attitudes hold true for listeners from other varieties of Spanish, as well. For example, Cuban Americans evaluate Peninsular Spanish as more “correct” than other varieties (Alfaraz, Reference Alfaraz, Long and Preston2002, Reference Alfaraz2014), and they associate it with high-status professions and family wealth much more than Latin American Spanish (Carter & Callesano, Reference Carter and Callesano2018). In another study, Latinx listeners in the United States rated a speaker of Peninsular Spanish as more competent than speakers of Latin American varieties (Callesano & Carter, Reference Callesano and Carter2019). These similar conclusions across studies highlight a widely shared perception that Peninsular Spanish is associated with status, education, and wealth.

Among non-Argentinian Latin American varieties, Colombian Spanish tends to be more positively regarded than other dialects. Luijpen (Reference Luijpen2012), for instance, found that, when explicitly asked what variety of Latin American Spanish they preferred, Spaniards evaluated Colombian Spanish more positively than other non-Argentinian varieties. In Alfaraz (Reference Alfaraz, Long and Preston2002, Reference Alfaraz2014), Miami Cubans gave high correctness ratings to Colombian Spanish, only trailing behind Peninsular and Argentinian varieties in the 2002 study, and Peninsular, Argentinian, Chilean, Costa Rican, and Venezuelan Spanish in her 2014 follow-up. Carter and Callesano also point out the widespread view of Colombian Spanish as “among the best, most pure, or most refined varieties of Spanish” (Reference Carter and Callesano2018:70), attributing it to the perception of Colombians as more middle-class and ethnically European.

What can explain these attitudes toward different varieties of Spanish? Ethnolinguistic theory (Giles & Johnson, Reference Giles and Johnson1987), which expands upon social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), proposed that language, being a core component of identity, can be used to create distinctions among groups. Language use associated with particular groups can evoke internalized stereotypes about these groups (Levon, Reference Levon2014). The evocation of these stereotypes involves a semiotic process of rhematization/iconization, by which the social image and the linguistic image become bound together in a way that seems inherent (Gal, Reference Gal2005; Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000). In other words, “…linguistic features are seen as reflecting and expressing broader cultural images of people and activities. Participants’ ideologies about language locate linguistic phenomena as part of, and evidence for, what they believe to be systematic behavioral, aesthetic, affective, and moral contrasts among the social groups indexed” (Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000:37).

With these linguistically and socially intertwined ideologies of differentiation in mind, it is unsurprising that speakers of privileged varieties often feel their dialects are superior to others (Adger, Wolfram & Christian, Reference Adger, Wolfram and Christian2007:9–11). Similarly, this hierarchical social organization of linguistic varieties can result in linguistic insecurity among speakers of less prestigious varieties (Labov, Reference Labov1972:132–33). However, other qualities intersect with language to influence perceptions of others; of crucial importance to the present study is how visual information sways listener judgments.

2.4 Visual cues and speech perception

Studies in sociolinguistic perception have demonstrated that social information about a speaker (introduced into the listening context in the form of pictures, video clips, or textual information) can influence speech perception (Drager, Reference Drager2005; Hay, Nolan, & Drager, Reference Hay, Nolan and Drager2006; Hay, Warren & Drager, Reference Hay, Warren and Drager2006; Kang & Rubin, Reference Kang and Rubin2009; Kutlu, Reference Kutlu2020; Niedzielski, Reference Niedzielski1999; Rubin, Reference Rubin1992; Staum Casasanto, Reference Staum Casasanto2010, among others). For instance, Niedzielski (Reference Niedzielski1999) and Hay, Nolan, and Drager (Reference Hay, Nolan and Drager2006) found that placing a label indicating a speaker’s country of origin in an experimental context affected listeners’ perception of vocalic variants. In both studies, participants were more likely to identify the vocalic realizations they heard as those stereotypically associated with a group of speakers when they were presented with the label for that group. Other studies have employed pictures to test the effect that socioeconomic class, age, and race had on the perception of phonetic variants. Hay, Warren, and Drager (Reference Hay, Warren and Drager2006) found that the visual manipulation of age and socioeconomic class had an effect on the participants’ accuracy in a vowel identification task. Staum Casasanto (Reference Staum Casasanto2010) examined the effects of speaker race on perceptions of word-final /t/ and /d/ deletion, a linguistic feature more frequently observed in the speech of African American speakers. She found that the presence of a photograph of an African American speaker triggered perceptions of final consonant deletion.

While the studies summarized above have focused on the effects of social priming on the perception of particular linguistic (mostly phonetic) variants, other research in this area has examined how social priming intersects with sociolinguistic evaluations of different language varieties. Studies in this area consistently demonstrate that, in daily interactions, speech perception does not occur in isolation. Rather, it is also conditioned by visual cues. In a seminal paper on the topic, Rubin (Reference Rubin1992) discovered that when participants listened to a class lecture given in American English paired with an Asian face, they provided higher evaluations of accentedness and understood less of the content than participants who listened to the same recording presented with a White face. Similar effects have been found in related studies. For example, Kutlu (Reference Kutlu2020) showed that when an American English accent is paired with a picture of a South Asian face, participants’ response times were faster, and they evaluated the voice as more accented than when presented with a White face. In their investigation of perceptions of Canadian English when paired with a White face and an Asian face, Babel and Russell (Reference Babel and Russell2015) also found higher accentedness ratings for the Asian Canadians and lower intelligibility scores.

In a related study, English monolingual and Spanish-English bilingual listeners were presented with differently accented speech samples (“Standard American English, Chicano English, and nonnative Spanish-accented English”) that were paired with “idealized ‘Hispanic’ or ‘non-Hispanic’” visuals (Gutiérrez & Amengual, Reference Gutiérrez and Amengual2016:55). The results show that listeners’ evaluations of proficiency, comprehensibility, and identification were influenced by both the accented speech sample heard and the visual used. Speakers who spoke a variety considered more “standard” were given more favorable evaluations of comprehensibility and proficiency, and no visual effect was observed. However, the visual did significantly condition evaluations of whether an individual spoke Spanish and whether the participant identified with the individual.

In other words, listeners may associate stereotypes with members of an out-group and utilize visual or linguistic cues to link individuals with those broader categories (see the Reverse Linguistic Stereotype Hypothesis [Bradac, Cargile, & Hallett, Reference Bradac, Cargile and Hallett2001; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960] and the Associative-Propositional Evaluation Model [Gawronski & Bodenhausen, Reference Gawronski and Bodenhausen2006]). A more recent theoretical framework that can account for the importance of visual information across studies is that of raciolinguistic enregisterment, which proposes that “linguistic and racial forms are constructed as sets and rendered mutually recognizable as named languages/varieties and racial categories” (Rosa & Flores, Reference Rosa and Flores2017:631). Building off of work on rhematization/iconization (Gal, Reference Gal2005; Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000), raciolinguistics centers racial categories and linguistic features in the semiotic process of meaning-making, suggesting that the two are “ideologically twinned” (Rosa & Flores, Reference Rosa and Flores2017:631).

3. Methodology

3.1. Experiment design

In order to examine the effects that language variety and visual information had on Spaniards’ perceptions of others, we designed an experimental survey that was distributed online using Qualtrics. In the survey, participants residing in Murcia, Spain listened to a man’s voice and were simultaneously shown a picture of a White or Mestizo face. As noted in Section 2.3, Liujpen (Reference Luijpen2012) documents a linguistic preference for peninsular accents among Spaniards and, within the context of Latin America, a preference for Argentinian Spanish over other Latin American varieties, among which Colombian Spanish is preferred. To account for these distinctions, and with the goal of comparing a local voice to nonstigmatized Latin American varieties that can also be frequently heard in Spain, one male voice from Murcia, Spain, another from Santa Fe, Argentina, and a third from Barrancabermeja, Colombia were included in the experiment, each selected from publicly available resources. The men were all approximately the same age (late 20s or early 30s), and their speech contained clear examples of the dialectal features typical of each variety. It is important to note that, among these stimuli, the audio file selected for Spain would be considered a local voice for the participants in the study.

In each recording, the men discussed a neutral topic for 15-30 seconds (see Appendix) without background noise or interruptions. While traditional matched-guise experiments (Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960) usually employ the same paragraph uttered by speakers (or a single speaker) of different language varieties, in this study we opted for prioritizing spontaneous speech samples over controlled readings for the sake of authenticity and naturalness. However, we acknowledge that differences in content between the speech samples used could potentially bias perception.

The three different voice recordings were paired with four different photographs (see Section 3.2), resulting in a total of twelve possible combinations. To decrease attrition and ensure that each participant only heard each voice and saw each photograph one time, the pictures and audio files were paired differently across four blocks. After reviewing the instructions and providing consent, participants were randomly assigned to one of these blocks.

Participants were then told they would listen to three people residing in Spain and that they should try to guess what they were like. They were asked to rate the speaker along a series of social and personal characteristics, using eight 6-point Likert scales: leadership, humorousness, intelligence, trustworthiness, religiousness, niceness, sociability, and likability. They were also asked to estimate the monthly salary, occupation, place of origin (by making a selection on a map), and education level of the man they heard and saw.Footnote 2 Finally, participants were asked to provide sociodemographic information about themselves, including their gender, age, education level, whether they had traveled to Latin America, and whether they had Latin American friends. Figure 1 provides an example screenshot of what participants saw on each evaluation page of the experiment.

Figure 1. Screenshot of one page of the experiment.

3.2. Picture evaluation task

The four stock photographs used in the experiment, included in Figure 2, were taken from Unsplash.com. In order to find Mestizo and White faces, we relied on the photographers’ own labelling system and searched for photographs that were tagged with the labels “Hispanic” or “Latino,” on the one hand, and “White” or “Caucasian,” on the other. Once selected, the photographs were independently tested to assess to what extent the manipulation of race and age was successful, as well as to examine what unforeseen social characteristics they might index. Using Likert scales, a group of 105 Spaniards, who did not participate in the auditory experiment, evaluated each photograph on scales of attractiveness, masculinity, and how Latin American the person pictured seemed to them. They were also asked to estimate the age, occupation, place of origin (by making a selection on a map), and education level of the man they saw. Each participant evaluated a single picture and, at the end of the survey, they were asked to provide sociodemographic information about their gender, age, education, place of residence, whether they had traveled to Latin America, and if they had Latin American friends.

Figure 2. Photographs used in the experiment.

Regression models were built in R (R Core Team, 2021) to evaluate the effect of photograph and participant characteristics on ratings and response variables. The results indicate that the pictures that were selected to depict a Mestizo man (photos 1 and 4) were rated as significantly more Latin American than those selected to portray a White man (photos 2 and 3). When asked to select the country of origin of the person shown in the photograph, participants most frequently placed the men shown in photos 2 and 3 in either Spain or Argentina, while the men pictured in photos 1 and 4 were more frequently located in Colombia or the “Other” category, which was triggered when the participant selected a place in the map that was not Colombia, Argentina, the Caribbean, Mexico, or Spain. The average estimated age was significantly different for each of the photographs. The man in photo 2 was rated as the oldest of the four (mean = 38.5 years old), followed by the men in photo 4 (mean = 34 years old) and photo 1 (mean = 31.4 years old), respectively. The youngest average age was assigned to the man depicted in photo 3 (mean = 23.2 years old). There were also significant differences in the attractiveness rating given to each photograph, such that the men in photos 3 and 4 were rated as significantly more attractive than the men in photos 1 and 2. No significant differences in education level or masculinity ratings were found between the pictures, and no participant variables had a significant effect on any of the ratings.

The results of the image evaluation task confirm that the photographs employed in the experiment index Latin American status in addition to attractiveness and age. These results were used to inform the statistical analysis and the interpretation of the results. However, it is important to note that the four pictures depict four different individuals and that there might be other factors related to their appearance that might bias how they are perceived.

3.3. Participants

Recruitment took place through established connections with faculty at the Universidad de Murcia and through social media. A total of 217 Spaniards living in Murcia participated in the experiment, which took about five minutes to complete. Among the participants, 147 were women and 72 were men, and their ages ranged from 18 to 72 years old. However, because many of the participants were university students, the average age was 26.3. With respect to education level, 70 participants said they had completed secondary education, while 116 said they had a university degree, and 33 a postgraduate degree (master’s or doctorate). A total of 183 participants said they had never traveled to Latin America, and 191 indicated that they did not have any Latin American friends.

3.4. Statistical analysis

Following data collection, responses to the checkbox variables were converted to numerical values. In order to do so, salary levels were ranked from lowest to highest. All scores were then centered and standardized. A factor analysis was conducted to consolidate variables that behaved similarly and to eliminate possible correlations between them using the factanal function in R (R Core Team, 2021). While there are no established criteria for a cutoff point that determines the inclusion of variables in a particular factor, we followed Weatherholtz, Campbell-Kibler, and Jaeger (Reference Weatherholtz, Campbell-Kibler and Florian Jaeger2014), using the Kaiser rule to determine the number of factors and the loading values of each variable to determine how much meaning each variable contributed to each factor. Factors whose eigenvalues were under 1 were not included in the analysis and loading values over 0.4 were considered to be sufficient for inclusion of a rating in a particular factor. The results show that of the ten variables, seven loaded onto two factors: a status factor (for leadership, intelligence, and salary) and a solidarity factor (for niceness, sociability, likability, and humorousness). Of the remaining variables, religiousness and trustworthiness did not load onto any factor, so they were considered separately.

For the occupation variable, participants’ responses, which corresponded to a specific professional field, were matched with a prestige score based on the occupational prestige scale developed for Spain by Carabaña Morales and Gómez Bueno in Reference Carabaña Morales and Bueno1996 (PRESCA 2). Because the resulting variable was abnormally distributed, we opted for transforming the numeric variable into two prestige categories, high and low, using the average value of 135.62 as a cutoff for each level.

Mixed-effects linear regression models were then fitted to lone and joint factors, using the lme4 package (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R. The resulting five models (with status, solidarity, religiousness, trustworthiness, and occupational prestige as the dependent variables) tested the effects of the following independent variables on each rating or joint factor:

-

- Voice: whether participants were presented with a recording of the Spanish, Colombian, or Argentinian voice.

-

- Pictured race: whether the photograph depicted a White or a Mestizo face.

-

- Pictured attractiveness: whether the photograph depicted a more or less attractive man (according to participants’ ratings in the image evaluation task).

The following listener variables were also considered in the analysis:

-

- Listener age: due to the skewed distribution of the age of the participants, a log-transformed factor was employed instead of the raw numerical value.

-

- Listener gender, as described by the participant.

-

- Listener education: transformed into a numerical value from lowest to highest level.

-

- Listener travel to Latin America: whether the listener indicated they had traveled to Latin America or not.

-

- Listener friends from Latin America: whether the listener indicated they had some friends from Latin America or whether they had few or none.

Because there was a strong association between all the listener variables, only one of them could be included in the regression analysis. A random forest was developed using the party package (Hothorn et al., Reference Hothorn, Peter Buehlmann, Molinaro and Van Der Laan2006) in R to evaluate the relative importance of the possible predictors of each dependent variable (Tagliamonte & Baayen, Reference Tagliamonte and Harald Baayen2012). For all the ratings and joint factors, the most important listener variable was listener age. Thus, we decided to include only this variable and to exclude listener education and travel and connections to Latin America from the analysis. Once the relevance of the remaining predictors was established, the independent variables were added to the regression model following a stepwise procedure based on the output of each random forest, and nested models were compared using ANOVA. In addition to main effects, all two-way interactions were tested, and participant was included in all models as a random intercept, with the exception of occupational prestige, where the effects of the random variable were too small to be considered.

4. Results

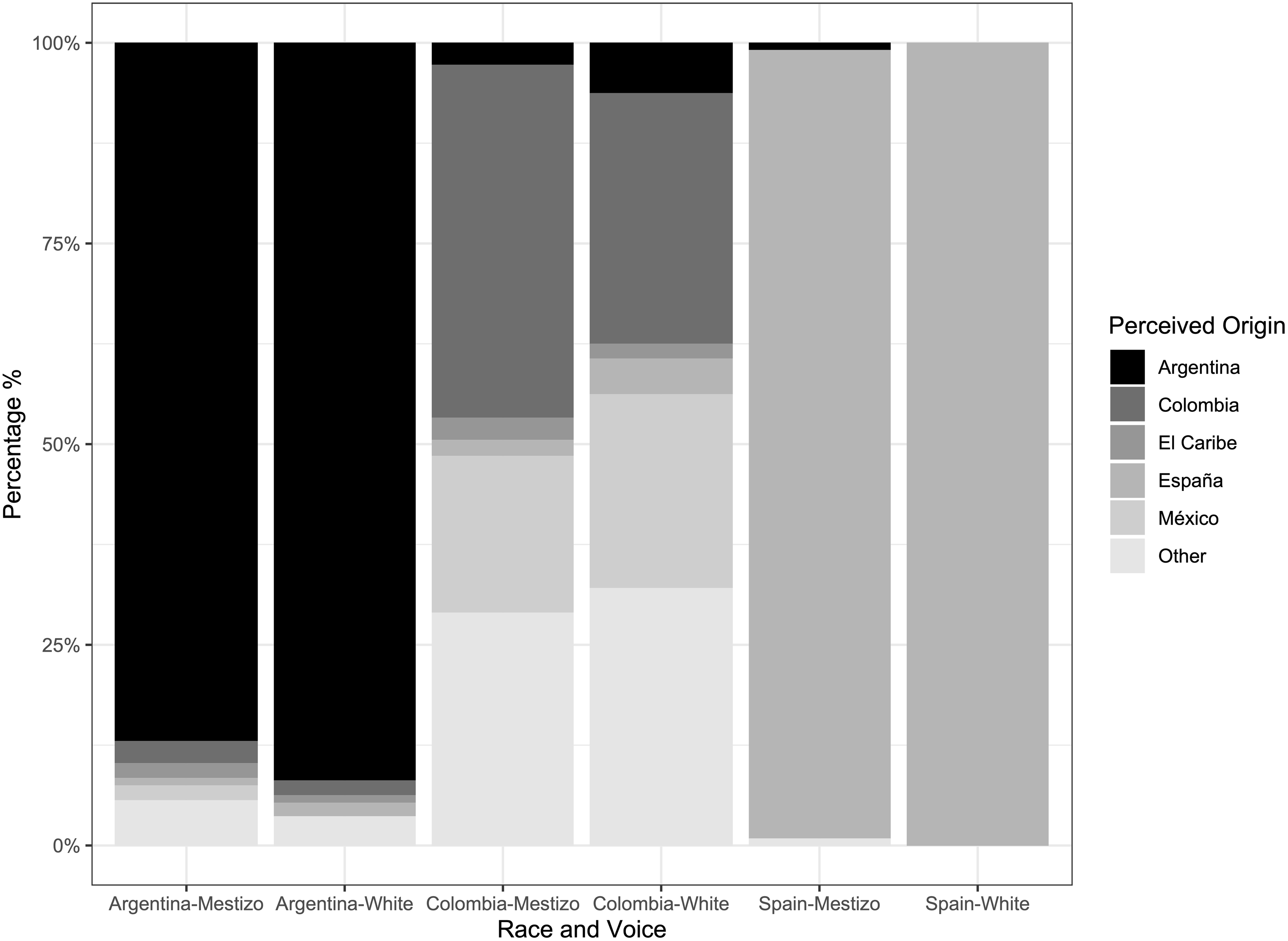

Before examining the results of the regression analyses for each lone and joint factor, we report on the distribution of the responses to the origin question of the survey, where participants were asked to select the geographic location from where they thought each speaker came. Figure 3 shows the distribution of responses by voice and photograph combination.

Figure 3. Distribution of responses to the perceived origin question by race and voice combinations.

The results show that participants were able to successfully identify the origin of the Spanish and the Argentinian voices, but they were less accurate in guessing the origin of the Colombian voice, with Colombia, Mexico, and Other being the most frequently selected categories. Thus, evaluations of the Colombian voice should be interpreted as evaluations of non-Argentinian Latin American speech. The distribution of responses also indicates that the participants overwhelmingly relied on the auditory signal to identify the origin of the speaker. While there were some differences in the selections between the voice primed with the photograph of a White man and the same auditory stimulus accompanied by the photograph of a Mestizo man, these differences were minimal, showing a slightly higher percentage of “Argentina” and “España” responses when the stimulus was paired with the photograph of a White man for the Latin American voices. The distribution of responses to the origin question in the image evaluation task shows that, without the auditory stimulus, participants associate the pictures of the White men with Spanish and Argentinian origins, while the pictures of the Mestizo men are more frequently assigned to non-Argentinian Latin American origins (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Distribution of responses to the perceived origin question by race in the image evaluation task.

The statistical analysis of listener evaluations generated different effects for each of the dependent variables included in the regression models. In the remainder of this section, we report the results for each joint and lone factor.

4.1. Status

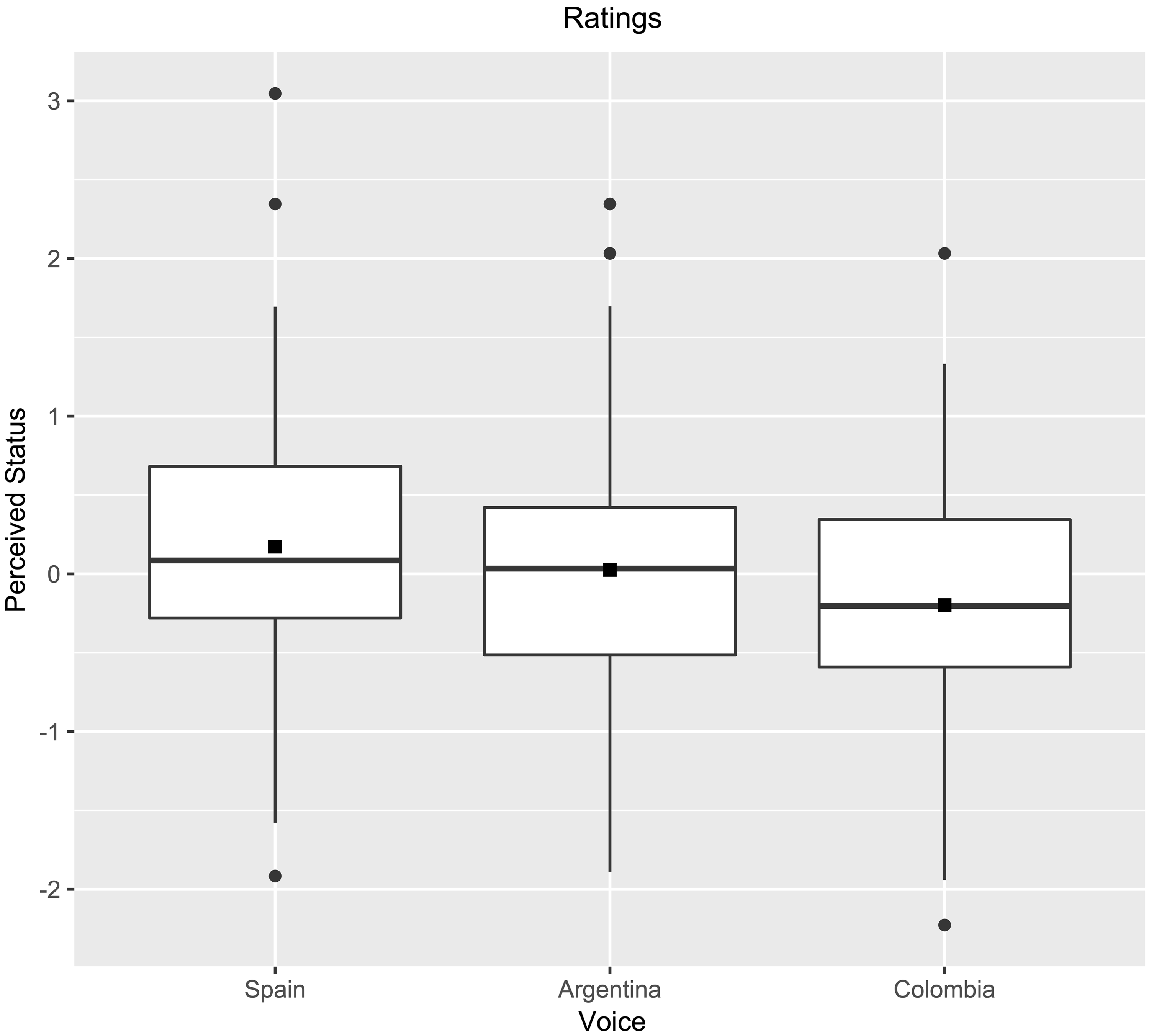

The results for the regression model for the status factor, summarized in Table 1, yielded significant main effects of participant age, the voice listeners heard, and the image paired with the auditory stimulus. Because the dependent variable was a numerical rating, positive estimate values indicate a higher status rating for each factor level. The table also includes standard errors (SE), t values and p values (alpha=0.05).

Table 1. Best-fit mixed-effects model of listener responses to the status rating. Significant factor levels are bolded. Reference levels are Voice = Spain and Image = Photo 3

The results show that the older the age of the participant, the lower their status rating of the speakers, independent of the voice or image presented in the stimulus. The findings also indicate that the Argentinian and Colombian voices were given a significantly lower status rating than the Spanish voice, with the Colombian voice rated the lowest in this category (also significantly lower than the Argentinian voice). The graph in Figure 5 illustrates the differences in status rating for the three voices. In this and all subsequent boxplots, each box in the graph shows the interquartile range of the score distribution. The horizontal line represents the median, the black squares inside the boxes represent the mean, and the dots above and below the boxes are outliers.

Figure 5. Perceived status rating by voice.

The individual image that accompanied the auditory stimulus also had a significant effect on status ratings such that the speaker was perceived as having a lower status when the voice was paired with photograph 3 than when it was paired with photographs 2 and 4. (The directionality was the same when compared to photograph 1, but the difference was not statistically significant.) Because the effect is restricted to a single photograph, using the results of the image evaluation task, we hypothesize that the lower status rating for photograph 3 may be attributed to the significantly younger age estimated for the individual pictured in that photograph. While the men in photographs 1, 2, and 4 were all, on average, estimated to be over thirty years old, the mean age attributed to the man in picture 3 was 23.2. Given that two of the three variables that were combined in the status factors, leadership and salary, are dependent on having acquired sufficient professional experience, it follows that seeing a younger face would elicit lower status ratings. No other listener variables or primed social factors for the speaker had a significant effect on the status rating.

4.2. Solidarity

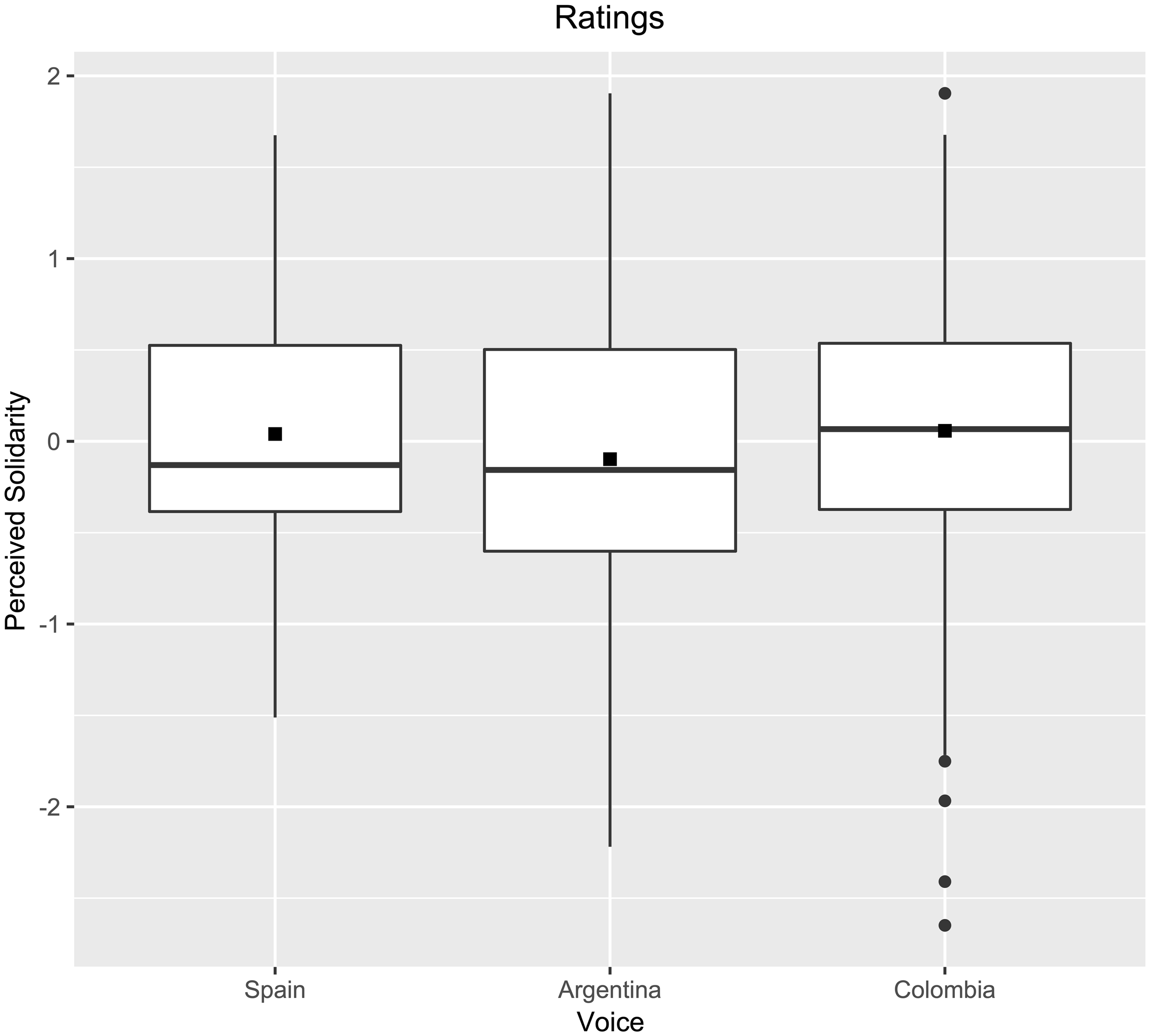

The regression analysis for the solidarity factor, which combined ratings for niceness, humorousness, kindness, and sociability, indicates that participant age and voice were significant predictors of the listeners’ ratings. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Best-fit mixed-effects model of listener responses to the solidarity rating. Significant factor levels are bolded. Reference level for voice is Spain

Similar to the status rating, the age of the participant had a significant effect on the solidarity rating such that older listeners, in general, gave lower ratings for this category. The voice participants heard was also a significant predictor of solidarity scores. In this case, the Argentinian voice elicited significantly lower ratings than the Colombian or the Spanish voices. The graph in Figure 6 illustrates the differences in solidarity rating among the three voices.

Figure 6. Perceived solidarity rating by voice.

4.3. Religiousness

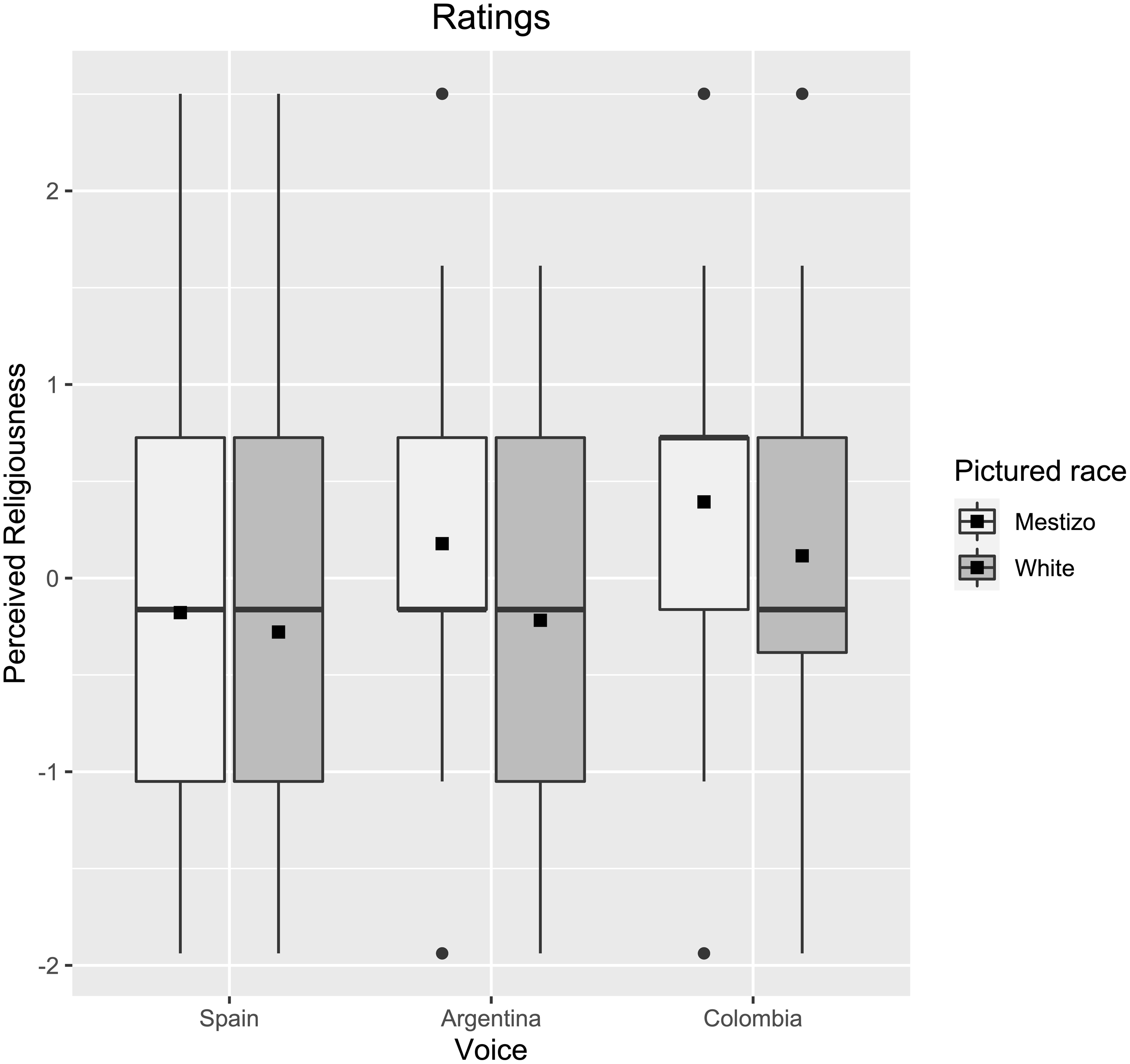

Religiousness was one of the two variables that did not load onto any factor, which is why it was considered separately. The results of the regression analysis, reported in Table 3, yielded main effects of voice and pictured race.

Table 3. Best-fit mixed-effects model of listener responses to the religiousness rating. Significant factor levels are bolded. Reference levels are Voice =Spain and Pictured race = Mestizo

The results indicate that listeners gave significantly higher religiousness evaluations when they heard the Argentinian and Colombian voices than when they heard the Spanish voice. Evaluations of the Argentinian and Colombian voices were also significantly different, with the Colombian voice perceived as the most religious. The second effect was that of pictured race. The results show that when listeners were presented with a photograph of a White man, they rated the speaker as significantly less religious than when they were presented with a photograph of a Mestizo man.

While pictured race is a significant predictor of religiousness for all voices (no significant interactions between the two predictors), the graph in Figure 7 shows that the effect of this factor is larger when the Argentinian and the Colombian voices were heard than when the Spanish voice was heard.

Figure 7. Perceived religiousness rating by voice and race.

4.4. Trustworthiness

The results for the regression analysis of the trustworthiness rating, which was also considered separately, show that only voice had a significant effect on listener evaluations of this trait. These results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Best-fit mixed-effects model of listener responses to the trustworthiness rating. Significant factor levels are bolded. Reference level for voice is Spain

The findings, represented in the graph in Figure 8, show that when participants heard the Argentinian voice, they evaluated the speaker as being significantly less trustworthy than when they heard the other two voices. No other main effects or interactions were found to be statistically significant in predicting trustworthiness ratings.

Figure 8. Perceived trustworthiness rating by voice.

4.5. Occupational prestige

As we explained in Section 3.4, due to the abnormal distribution of the occupational prestige data, responses to this variable were classified as either low or high prestige. A regression model was also fitted to the data, using occupational prestige as the categorical dependent variable. A random intercept was not included in this case because the analysis revealed that the between-subject variance was too low. The results, summarized in Table 5, show that only voice was a significant predictor of occupational prestige. In this case, because the dependent variable is categorical, positive estimates in each factor level indicate an increased likelihood of being assigned to the high occupational prestige category (the reference level for the dependent variable).

Table 5. Best-fit mixed-effects model of listener responses to the occupational prestige response. Significant factor levels are bolded. Reference level for voice is Spain

The findings show that the odds of the Colombian voice being assigned to the high prestige category are significantly lower than those of the Spanish voice, indicating that participants were more likely to judge the Colombian speaker as having a profession among those classified in the low occupational prestige category. The differences between the evaluations for the Argentinian and the Colombian voices were also statistically significant, with the former being more frequently assigned to a high-prestige professional field. These results are congruent with the observations for the status category reported in Section 4.1.

5. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that both linguistic variety (Argentinian, Colombian, or Spanish) and pictured race (Mestizo or White) condition participant evaluations of an individual’s social properties. More specifically, linguistic variety alone conditioned evaluations of status, occupational prestige, solidarity, and trustworthiness. In terms of status, the Spanish voice was attributed significantly higher status than the Argentinian voice, which was, in turn, viewed as having a higher status than the Colombian voice. Evaluations of occupational prestige followed suit, with the Spanish voice receiving the highest ratings and the Colombian voice the lowest. These findings largely confirm what other perception studies have claimed: Spanish voices are often linked with status, education, and wealth when compared to other varieties of Spanish (Alfaraz, Reference Alfaraz, Long and Preston2002, Reference Alfaraz2014; Callesano & Carter, Reference Callesano and Carter2019; Carter & Callesano, Reference Carter and Callesano2018; Luijpen, Reference Luijpen2012). While listeners were able to accurately identify the Argentinian voice, they were less successful in locating the Colombian voice, frequently selecting Mexico or other non-Argentinian Latin American countries as the origin of the speaker. Thus, in our discussion, we interpret results for the Colombian voice as evaluations of non-Argentinian Latin American speech.

Within the Latin American context, Luijpen (Reference Luijpen2012) found that Spaniards showed a strong preference for Argentinian speech. The higher status and occupational prestige ratings attributed to the Argentinian voice in our study support Luijpen’s observations and can be traced, in part, to the migration patterns between Argentina and Spain and the resultant sociohistorical connections between the countries. Because Argentina was an important locus of Spanish emigration in the nineteenth and earlier twentieth centuries, most Argentines have a long history of established family connections in Spain, which affords them expedited citizenship under Spain’s special kinship policies (Gratius, Reference Gratius2005). These preferential policies facilitated early waves of Argentinian immigration in Spain, which, driven by political exile, date back to the late 70s and 80s. Other Latin American immigration in Spain saw its largest increase recently, at the turn of the twenty-first century, giving Argentines a historical advantage over other Latin American immigrants both in terms of family ties and established immigration in the country. This might explain why listeners in our study were much better at identifying the Argentinian voice than the Colombian one.

The sociohistorical proximity between Spain and Argentina has resulted in a heightened visibility of Argentines in the Spanish media, enhancing their perceived status in Spanish society. On the one hand, the large number of Argentines that work in Spanish media and the positive reception that Argentinian film and theater have traditionally enjoyed in Spain have contributed to the cultural and linguistic knowledge that Spaniards have of Argentina (García, Reference García2006). On the other hand, Argentines are often portrayed in a positive and solidary light in the Spanish press; reporting on the Argentinian financial crisis positioned Argentines as victims of a corrupt system with which Spaniards can readily identify (Retis, Reference Retis2004). In contrast, media discourse about Colombian migration centers around violence, drugs, and social conflict, creating an image of a dangerous “other” that has the potential to destabilize peaceful coexistence with other residents, and Ecuadorians are rhetorically infantilized, with the media paternalistically highlighting their exploitation in the labor market. In other words, Spaniards receive greater exposure to Argentines and Argentinian culture in the media, where they are discursively presented as sympathetic peers, unlike other Latin American groups.

Another related factor that might explain the differences in the listeners’ status ratings for the Argentinian and Colombian voices is the professional profile of both groups of immigrants in Spain. The majority of Argentines that migrated in the 70s and 80s belonged to highly educated middle-class social groups. Thus, upon arriving in Spain, they frequently worked in relatively prestigious occupational fields (Vicente, Reference Vicente Torrado2006:9), inserting themselves into the same professional space as Spaniards and working in competition with them. Consequent waves of Argentinian migration were viewed from this frame of reference, providing newly arrived Argentines with a privileged status. Without this sociohistorically privileged status, other and more recent Latin American immigrants were more likely to work in unskilled jobs, mainly in the service and agricultural industry. This is not necessarily due to a lack of qualifications among these immigrant groups, but rather to current restrictions in access to the job market (Bekenstein, Reference Bekenstein2009; García Ballesteros, Giménez Basco & Redondo González, Reference García Ballesteros, Jiménez Basco and Redondo González2009; Vicente Torrado, Reference Vicente Torrado2006).

Although the Argentinian voice was evaluated as having a higher status than the Colombian voice, it was also perceived as significantly less trustworthy, and it received lower solidarity ratings than both the Spanish and Colombian voices, which were not significantly different from each other in either scale. These findings illustrate the competence versus warmth dichotomy that has been shown to underlie group stereotyping in social psychology (Cuddy, Fiske & Glick, Reference Cuddy, Fiske and Glick2008; Fiske et al., Reference Fiske, Cuddy, Glick and Xu2002). Research in this field has shown that beliefs about social outgroups can be organized along the two dimensions. High-status, competitive groups are frequently rated higher in competence dimensions (status and occupational prestige in our study), while low-status, noncompetitive groups normally receive higher ratings in evaluations of warmth (solidarity and trustworthiness in our study). High ratings along both warmth and competence dimensions are usually reserved for in-group evaluations, which explains why participants gave the highest ratings in all categories to the Spanish voice. Examining the existing stereotypes about Argentines in Spain corroborates our findings. For instance, Bekenstein (Reference Bekenstein2009) highlights that, despite the favorable attitudes that exist toward Argentines in Spain, they are still considered foreigners and are susceptible to discrimination. The author adds that Argentines frequently elicit mistrust, not only among Spaniards but also among other Latin American groups. They are also often perceived as arrogant and egocentric due to their alleged self-identification as “first-class” immigrants (Bekenstein, Reference Bekenstein2009; García Santiago & Zubieta Irún, Reference García Santiago and Irún2006).

Finally, both linguistic variety and race altered evaluations of religiousness in our experiment. With regard to voice, the Colombian voice was perceived as the most religious, and the Argentinian voice was also considered significantly more religious than the Spanish voice. These voice-based evaluations, to some extent, mirror citizens’ expressed religious commitments across these countries. According to the Pew Research Center, 80% of Christians in Colombia said religion is very important in their lives,Footnote 3 as compared to 48% in Argentina and 30% in Spain (Pew Research Center, 2018). However, this picture is complicated by the effect of pictured race. When the audio files were paired with a Mestizo face, the Spanish participants’ evaluations of religiousness increased significantly for both the Colombian and Argentinian voices. However, this same race-based effect was not observed for the Spanish voice. How can we explain the difference between the Latin American voices and the Spanish voice? The Reverse Linguistic Stereotype Hypothesis (Bradac, Cargile & Hallett, Reference Bradac, Cargile and Hallett2001; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Hodgson, Gardner and Fillenbaum1960) and the Associative-Propositional Evaluation Model (Gawronski & Bodenhausen, Reference Gawronski and Bodenhausen2006) have contended that out-group members are likely to be associated with stereotypes, and faster response times for out-group voices and faces suggests that listeners rely on mental shortcuts as they evoke these stereotypes (Kutlu, Reference Kutlu2020). In our experiment, the Mestizo faces seem to evoke stereotypes about higher rates of religiousness, but these mental shortcuts are only employed for out-group voices, not the local voice.

To situate this finding within a more linguistic framework, linguistic features become associated with a specific group of people (e.g., Latin Americans) through rhematization (Gal, Reference Gal2005; Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000), and, by extension, ideologies link those people with stereotypical characteristics (e.g., Mestizo and higher levels of religiousness). Participants in our experiment overwhelmingly placed the Spanish and Argentinian voices as coming from Spain and Argentina, respectively, and, while place of origin evaluations for the Colombian voice were more varied, including Mexico, Colombia, and other Latin American countries, the speaker was still positioned as Latin American. Similarly, as our picture evaluation task made clear, participants believed that the men with more Mestizo faces were significantly more likely to be from Latin America than the men with Whiter faces. Taken together, these findings underscore the “ideological twinning” of race and linguistic variety in the minds of the participants, whereby the two are constructed as sets in the process of raciolinguistic enregisterment (Rosa & Flores, Reference Rosa and Flores2017:631). To borrow a phrase from Rosa (Reference Rosa2019), in our participants’ minds the people they evaluated looked like a language (variety) and sounded like a race.

These experimental results complicate the idea of symbolic boundaries (i.e., based on race, language, religion, etc.). The present study demonstrates that the symbolic boundaries commonly applied to Latin American immigrants in Spain are not discrete categories but rather overlapping concepts. Perhaps the overlapping nature of these categories has enabled scholars to downplay the importance of race as a factor in anti-immigrant sentiment in Spain in previous studies (Molina Luque, Reference Molina Luque1994) in spite of immigrants’ self-reports of race-based discrimination (Flores, Reference Flores2015). Because many of these symbolic boundaries are constructed as ideologically twinned sets, race may also overlap with religion (or degree of religion) and language (or language variety), among other symbolic boundaries—any one of which could potentially be specified as the determining factor in Spaniards’ sentiments toward immigrant groups.

The configuration of these overlapping boundaries may contribute to attitudes toward and, ultimately, the experiences of immigrants in Spain. While pictured race did not impact participant evaluations to the same extent as linguistic variety in our experiment, it did reinforce certain stereotypes. Particularly when congruence was observed between participants’ linguistic and visual expectations for Latin Americans (i.e., when a voice perceived as more Latin American was paired with a Mestizo face, which was also perceived as more Latin American), stereotypes about religion were enhanced. This finding suggests that the more symbolic boundaries overlap for migrants in Spain, the more pronounced stereotypes will be toward those individuals, which may result in differential treatment. For example, previous research has indicated that as non-White immigrants become acculturated in Spain, they report less nationality-based discrimination but more racially-based discrimination. However, when White immigrants from Eastern Europe and the Southern Cone acculturate, they do not report racial discrimination, which suggests that whiteness decreases the barriers to integration (Flores, Reference Flores2015). García’s (Reference García2006) study supports this observation, highlighting the racial similarities between Spaniards and Argentines as a determinant of cultural acceptance. According to the author, Argentines’ European descent and whiteness grants them a “physical invisibility” that shields them from racial profiling.

It bears repeating that specific symbolic boundaries, such as racial boundaries, are neither rigid nor objective; rather, they are malleable and depend crucially on the history of the immigrant group and the receiving society (Alba, Reference Alba2005). Given the history of reciprocal immigration between Spain and Argentina, their close social and cultural connections, and the presentation of Argentines as sympathetic peers in Spanish media, Spaniards may conceptualize Argentines as falling on the same side of the racial symbolic boundary as they do. However, some level of erasure (Irvine & Gal, Reference Irvine, Gal and Kroskrity2000) of racial nuance is necessary for this ideology of racial sameness to flourish. As is the case in other Latin American countries, mestizaje is common in Argentina, but national discourse centers the country’s European roots and downplays racial mixing (Wade, Reference Wade and Poole2008). In other words, symbolic boundaries revolving around race or language, for instance, do not provide measures of intergroup difference, but rather highlight underlying ideologies about immigrant groups. Importantly, our findings indicate that these existing ideologies can be strengthened when racial and linguistic information are layered in congruence with existing stereotypes about Latin America, suggesting that migrants may be susceptible to increased barriers to integration when multiple symbolic boundaries overlap.

6. Conclusion

This study has explored how linguistic variety (i.e., Spanish, Colombian, and Argentinian) and race (i.e., Mestizo or White) condition Spaniards’ evaluations of others in an increasingly diverse society, finding that both factors play a role as Spanish participants situate others in social space. We contended that the bidirectional historical and sociocultural relationship between Spain and Argentina, the strong representation and positive portrayal of Argentines in the media, and the prestigious occupations held by early Argentinian immigrants in Spain help explain the higher status evaluations the Argentinian voice received when compared to the Colombian voice. However, we also showed that the Colombian voice was evaluated more positively for trustworthiness and solidarity than the Argentinian voice, which underscores the persistent mistrust elicited by Argentines who, as high-status outsiders, are perceived as being arrogant and in direct competition with Spaniards. Finally, we posited that when language variety and race are congruent with existing stereotypes about Latin America, perceptions of social distance (e.g., religiousness) increase, demonstrating that linguistic and visual information work together to condition and mutually reinforce Spaniards’ views of migrants. However, a great deal of work is still needed to better understand this complex phenomenon and improve upon the limitations of the current study.

First, we acknowledge that, as suggested by Carter and Callesano (Reference Carter and Callesano2018), the use of dialect labels delimited by country (e.g., Colombian, Argentinian, Spanish), the approach we have employed throughout this paper, can be a problematic practice. The labels themselves may imply that these samples are representative of the speech spoken in that region when, in reality, numerous varieties of Spanish and other languages coexist within the borders of the countries discussed here. Similarly, the terms could suggest the clear existence of national linguistic boundaries when, in reality, these boundaries are merely social constructions. Future studies should work to establish a methodology that better accounts for the linguistic diversity of the Spanishes spoken in different countries beyond the psychosocial simplifications adopted in this paper.

Second, we recognize that our methodological approach could have, to some extent, influenced the results presented here. As reported in Section 4, listeners relied primarily on the linguistic signal as they made social evaluations. While previous research has found that social information about the speaker can bias sociolinguistic perception, listeners are more likely to use this information when the linguistic signal is ambiguous (Drager, Reference Drager2005; Juskan, Reference Juskan2018; Staum Casasanto, Reference Staum Casasanto2010). In our experiment, however, the signal was not ambiguous; participants received ample linguistic information (a paragraph-length sample of the speaker’s variety), which was the primary contextual cue used to situate speakers in geographic and social space. This finding echoes those of other studies that have employed different linguistic varieties and more limited social or visual information in their methodology (e.g., Callesano & Carter, Reference Callesano and Carter2019; Carter & Callesano, Reference Carter and Callesano2018; Gutiérrez & Amengual, Reference Gutiérrez and Amengual2016). Future studies should modify the distribution of social/visual and linguistic information by, for example, including videos rather than images or limiting the linguistic features that could be used to identify the speakers’ origins. Altering the methodology in this way could shed light on how the experimental design itself influences participants’ responses to linguistic and social information.Footnote 4

In spite of the limitations outlined above, this project has advanced the academic conversation about immigration in an increasingly globalized world by adopting a transdisciplinary perspective, drawing from linguistics, anthropology, sociology, and social psychology. This discussion has contributed to our theoretical understanding of how language and race mutably influence the ideologies of members of the receiving society. Importantly, our findings are also relevant in a more concrete, practical sense, as these ideologies may, in turn, influence the symbolic boundaries established between groups and the social boundaries that foment discrimination or impede integration.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the Fulbright US Scholar Program for making this experiment possible, Juan Manuel Hernández Campoy and Juan Antonio Cutillas Espinosa for their helpful suggestions about the experimental design and language, Ana Isabel Foulquié Rubio, Sofía Virgili Viudes, and Christina Martínez Sánchez for their assistance recruiting participants, and the audience at the Tenth International Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics for their insightful feedback on an earlier version of this paper. We would also like to thank our participants for generously sharing their time and thoughts with us.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Appendix

Auditory experimental stimuli heard by all participants, organized below by language variety.

Argentinian voice

“Y los llaman a entrenar. Hacen un campo, ponele, de tres o cuatro días donde hacen trabajos de fundamento, muchos juegos, pero obviamente que no quedaban todos. A lo mejor reclu– llamaban quince chicos y quedaban cuatro.”

“And they call them up to train. They do a camp, let’s say, for three or four days where they work on fundamentals, a lot of games, but obviously not everybody stayed. Maybe they recrui– they called up fifteen guys and four stayed.”

Colombian voice

“Esta zona es muy húmeda, y es muy calurosa. El ambiente es muy festivo, es muy alegre. La capital del país es mucho más una ciudad grande con los– la agresividad de una ciudad grande, los problemas de transporte, etcétera, y la gente es más cerrada.”

“This zone is very humid, and it’s very hot. The atmosphere is very festive, it’s very happy. The capital of the country is much more a big city with the– the aggressiveness of a big city, transportation problems, etcetera, and the people are more closed-off.”

Spanish voice

“Bueno, la preparación diaria, básicamente a la hora del trabajo, principio de la mañana, se realiza una revisión de todo el material, instalaciones y demás – se repone o se arregla el material que pueda estar defectuoso. Luego, se realiza la práctica diaria. Siempre hay una práctica diaria, pues, que, que viene desde la jefatura, viene determinada. Luego, la hora de la comida y demás y ya por la tarde, o sea, el ejercicio físico que también lo tenemos obligatorio.”

“Well, the daily preparation, basically at the start of work, first thing in the morning, all the equipment is reviewed, the facilities and all of that – the equipment that could be defective is replaced or repaired. Later, daily practice takes place. There’s always a daily practice, well, that, that comes down from the leadership, it’s already determined. Next, it’s lunch time and all that and then in the afternoon, I mean, there’s physical exercise that’s also mandatory for us.”