INTRODUCTION

Academic research on Chinese citizens petitioning the authorities in person or on paper (xinfang, “letters and visits”) began around the mid-1990s. Early studies viewed letters and visits as a form of social resistance in which the masses use state policies to struggle with local officials, and in this sense, the practice was termed “rightful resistance” (O'Brien and Lianjiang Li Reference O'Brien and Li1995; O'Brien Reference O'Brien1996). Recently, more and more studies confirm that the letters and visits system provides a channel for citizens to raise “useful complaints,” spurring local governments to make substantial improvements. In this way, the system introduces a measure of checks and balances into the Chinese authoritarian regime (Chen Reference Chen2012; Chen Reference Chen2016; Dimitrov Reference Dimitrov and Dimitrov2013; Yu Reference Yu2010).

The topic of our present study is a subtopic of letters and visits that has received little attention thus far: irregular letters and visits (irregular petitions, fei zhengchang shangfang). “Regular petitions” are those that conform to the relevant guidelines in the letters and visits regulations in that they are directed at officially designated letters and visits organizations and are passed up the hierarchy (z huji shangfang). This latter means that complaints must first be filed with the county-level letters and visits bureau (xinfangju). Then, if the problem is not resolved, the petition is passed up the hierarchy of letters and visits organizations until it reaches national level. What are defined in this study as “irregular petitions” are those that do not conform to the law, i.e., those that bypass lower-level authorities and go straight to the top (yueji shangfang). Many citizens take their grievances directly to Beijing,Footnote 1 and these petitions are deemed to have “not been filed according to the law.”

So, there are two ways in which “irregular petitions,” as defined in this study, are unlawful. First, they are petitions filed in venues or to organizations other than the officially designated letters and visits bureaus. Second, they are petitions that bypass the lower-level authorities, particularly those filed directly in the capital. Citizens choose to take their petitions directly to the top because they believe that petitions made in Beijing, particularly those made outside the Beijing Letters and Visits Bureaus or even the State Bureau for Letters and Visits, are more likely to attract the attention of the government and force officials to act. These petitions often involve sensitive and complex issues that petitioners believe cannot be resolved to their full satisfaction by the local authorities.

In brief, a petition is deemed to be irregular if it is directed at any organization other than the designated ones. Beijing is the most popular place for irregular petitions—in Tiananmen Square or around Zhongnanhai, for example, or in the embassy district,Footnote 2 near the residences of the central leaders (mainly Jade Spring Hill Yuquan Shan), or the venues of various important meetings and the accommodation where the attendees are lodged.Footnote 3 If citizens attempt to petition at these locations, security personnel are dispatched to escort them away.Footnote 4 The local authorities in the petitioners’ home provinces are notified and they are returned to their home areas.

Although the study of irregular petitions is of great academic value, the topic has received almost no attention in the scholarly literature. The main reason petitioners resort to irregular means is that their regular petitions have been ineffective. But irregular petitions present a greater threat to social stability than regular ones.

In recent years, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has adopted a combination of “hard” and “soft” measures in its management of irregular petitions. During normal times, cadres tend to use soft measures like persuasion and exhortation to get petitioners to abandon their irregular petitions, because these are relatively low-cost measures. But during exceptional periods, including major political conferences or public holidays, cadres tend to use hard measures more often than soft ones as maintaining social stability is a top priority. Hard measures include compelling the petitioners to leave Beijing or detaining them. We use the concept of the “temporally differentiated response” (fenshi huiying) to describe this phenomenon.Footnote 5 We lay emphasis on this use of a combination of soft and hard measures to manage social contention. However, it is apparent that the ratio of soft to hard measures differs between normal and exceptional times.Footnote 6

This study aims to clarify the means and logic of the CCP's social control. Particularly, we try to explain why local officials are prone to use this control strategy rather than other methods during specific periods. In previous literature, there has been a lot of discussion about how local governments maintain social stability (Teets Reference Teets2014). We want to explore further whether local officials have different disposal patterns during different “periods.” Some scholars believe that the CCP has adopted many soft practices to maintain social stability in recent years.Footnote 7 Others hold that the CCP still adopts harsh punishment methods for social supervision and control, for example, through the power of the public security system (Wang and Minzner Reference Wang and Minzner2015). These opinions might be correct, but they are not comprehensive. The authors of this article believe that only by observing whether the CCP adopts different practices for social control during different periods can we have a more complete understanding of this topic.

This study examines one specific case in order to better understand how the CCP maintains social stability and to identify the characteristics and essence of its political authority. The authors selected Province A and one of the cities under its jurisdiction, City T, for this case study. Between February 2016 and December 2017, the authors visited the letters and visits bureaus, political and legal commissions, and public security bureaus of Province A and City T to collect relevant information. We investigated the subjects of the irregular petitions filed in Beijing by citizens from City T, and we examined the units that deal with irregular petitions in that province and city, so as to gain a better understanding of how these units operate and coordinate with one another while dealing with irregular petitions filed in Beijing by residents of City T.

In addition, we interviewed 43 officials and 21 petitioners, read a large number of unpublished official documents, and examined statistical material to obtain sufficient raw data for the study of irregular petitions. We also obtained statistics on petitioners from City T who visited Beijing between 2014 and 2016. During that period, there were a total of 722 petitioners from City T, 287 of whom were involved in regular petitions and 435 (60.2%) in irregular petitions. In addition, we obtained documents that reveal how the local government handled these irregular petitions.Footnote 8 Below, we outline the analytical framework of this study and the research we carried out to validate our opinions.

TWO TYPES OF STRATEGIES HANDLING IRREGULAR PETITIONS IN CONTEMPORARY CHINA

When faced with a crisis in society, the CCP uses the “carrot and stick” or “hard and soft” (ruanying jianshi) approach to resolve the problem (Sun and Guo Reference Sun and Guo2000; Hu, Wu, and Fei Reference Hu, Wu and Fei2018). For less important issues, the CCP adopts a soft approach, but when it is more seriously challenged, it is prepared to adopt harder measures that involve expending more national and social resources (Brady Reference Brady2009). These exigent measures are too costly for long-term use and can only be used sporadically or during especially sensitive periods. In normal times, the CCP must adopt softer, lower-cost measures to deal with petitions. In this study, we propose the concept of the temporally differentiated response, which categorizes the times at which petitions are presented as either “normal” or “special” (i.e., politically sensitive). In normal times, the CCP tends to favor a soft approach, while in special times it is prepared to use a hard approach.

We provide three examples to illustrate the soft and hard approaches. The soft tricks include actual bribery, emotional bribery, and persuasion via friends/relatives, whereas the hard measures include restrictions on entering Beijing, forced return and detention, and prosecution. The biggest difference between the soft and hard approaches is that soft measures focus on psychological manipulation, encouraging petitioners to withdraw their complaints voluntarily.Footnote 9 This concept is similar to the “psychological coercion” proposed by Kevin J. O'Brien and Yanhua Deng (Reference O'Brien and Deng2017). In an example of the soft approach, O'Brien and Deng describe how the Chinese authorities, when trying to evict residents so they can demolish their homes, often get the relatives of the homeowners to put emotional pressure on their family members so they eventually agree to leave voluntarily(O'Brien and Deng Reference O'Brien and Deng2015). The hard approach, on the other hand, involves physical coercion, such as forcing petitioners to leave Beijing. The state usually employs the police, military units, the courts, or other coercive institutions to carry out such hard measures.

We can therefore identify two types of strategies of social control within the CCP regime—one hard and one soft.Footnote 10 One example of soft power is the way in which the CCP, as part of its united front process, makes use of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) and semi-official social organizations to incorporate or absorb new social classes, which can be viewed as an example of infrastructural power (Dickson Reference Dickson2003). The CCP also uses “soft control” to deal with threats to social stability. As Deng and O'Brien have noted, in recent years the CCP, in dealing with social protests, has adopted the method of “relational repression,” which consists of using persuasion and applying pressure via the friends and relatives of protesters to undermine their anti-government activities (Deng and O'Brien Reference Deng and O'Brien2013). Teets (Reference Teets2014) believes that having experienced a large number of major protests, the CCP has realized that it can promote dialog with the people by opening up membership of social organizations and implementing various control measures with regard to social groups. This not only helps steer public thinking but also promotes social stability.

Then there are the “hard” measures. The CCP considers that its primary duty is to maintain political stability. As Deng Xiaoping said in 1990, “stability trumps all.”Footnote 11 This is the premise that underpins all the CCP's policies to the present day (Benney Reference Benney2016). To ensure the survival of its regime, the CCP devotes its many resources to maintaining social stability. It views all protest activities, such as parades, demonstrations, strikes, merchant strikes, and petitions, as disorderly and chaotic, and it is willing to go to any lengths to suppress and combat them. As part of its effort to maintain stability, the CCP has raised the status of the public security bureau within the bureaucratic system and has made “maintaining stability” an important indicator in the cadre evaluation system (Wang and Minzner Reference Wang and Minzner2015). Other studies have noted the important role of the armed police in the overall maintenance of social stability (Guo Reference Guo2012, 221–253). This is a sign of how the state is prepared to use “hard” measures to maintain its monopoly on violence and suppress and dominate individual citizens and society as a whole.

The CCP's internal letters and visits system makes use of these two kinds of measures, as shown in Figure 1. In normal times, cadres are more likely to use persuasion and inducement to get citizens to stop petitioning. Prior to 2013, many local cadres would hire gangsters to compel petitioners to withdraw their petitions by, for example, seizing their cell phones and identification documents and sometimes even abusing or attacking them (Chen Reference Chen2017),Footnote 12 but these practices are now strictly forbidden. The CCP has clearly specified that petitioners may not be subjected to “barring, stopping, blocking, intercepting” (lan, ka, du, jie) and other such practices.Footnote 13 This has prompted local cadres to switch to more flexible methods of exhortation, persuasion, and the like to get aggrieved citizens to desist. However, at times when hard measures are called for, cadres will use coercive or violent means to force petitioners to return home.

Figure 1 Two Kinds of Measures for Handling Irregular Petitions

Figure 1 illustrates this study's overall analytical framework. The circumstances that determine how irregular petitions are dealt with are categorized as either normal or special (such as during important conferences or public holidays). In normal circumstances, petitions are handled through the letters and visits system, while in special circumstances the political and legal system takes the lead. This is because during special periods, the stakes of maintaining social stability are extremely high. Therefore, the CCP transfers the power to deal with irregular petitions from the letters and visits system, which generally adopts a soft approach, to the higher-level, more powerful Political and Legal Affairs Commission (PLAC, zhengfawei) which uses harder measure and devotes more resources to discouraging irregular petitioners from going to Beijing. For example, in the case study used in this paper, the letters and visits bureau of Province A handles irregular petitions filed in Beijing by citizens from City T in normal times, but in special times, this authority is passed to the province's commission for political and legal affairs. Below, we will provide details of the three specific measures adopted by each of these systems, thus demonstrating the local officials’ temporally differentiated response to irregular petitions.

WHY THE TEMPORALLY DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSE? EXPLANATIONS ARISING FROM THE OPERATION COSTS OF HARD MEASURES AND THE CADRE EVALUATION SYSTEM

Here, we try to determine why local officials adopt temporally differentiated responses—soft in normal times and hard during special times—to irregular petitions. When we discuss the social stability maintenance work from the perspective of the relationship between the central and local governments, it can be seen that local officials are in a relatively weak position. It is mainly manifested in two aspects: first, in consideration of the overall national finance, the central government hopes that local officials can deal with more things with the least administrative resources. In other words, the resources of local governments are limited, and it is not easy to strive for more resources from their superiors. Second, during the most sensitive period, the central government hopes that local officials can try their best to achieve social stability, which is reflected in the indicators of performance evaluation for local governments. These two factors request local officials to make rational choices to maximize their administrative achievement (Whiting Reference Whiting2001). Above all, owing to the financial deficits, local officials have to use low-cost soft tricks to solve the problems of irregular petitions more often in order to avoid slashing other budgets of local governments. Next, for the sake of the evaluation indicators, local officials have to meet the requirements for social stability maintenance at all costs during sensitive periods. Therefore, hard measures will be used more often during such periods than that during normal periods. We will illustrate them in sequence below.

Soft tricks tend to be favored during normal times because they are less costly than hard measures. Hard measures involve arresting petitioners and returning them to their homes under a three-person escort consisting of a police officer, a letters and visits cadre, and a government leader. Taking room and board, travel, and other expenses into account, returning a petitioner costs the local government at least RMB50,000. This must be paid by the petitioner's own township. Since a township's annual administration budget is only around RMB400,000, this outlay is extremely burdensome for a local government.Footnote 14 Soft tricks, such as persuasion, come at a much lower price. As one secretary of a township Party committee commented, “If our township government gives a petitioner RMB1,000–2,000 to buy them off, they will not go to petition; this is very economical for us.”Footnote 15

In addition to the monetary cost involved, hard measures require cadres to expend a great deal of effort. For example, if a group of irregular petitioners goes up to Beijing, local government leaders are kept constantly on the run. Province A has stipulated that for groups of three or four irregular petitioners, the secretary of the township Party committee or the township mayor must go in person to Beijing to bring them back. For groups of between five and ten petitioners, the secretary of the county Party committee or the county mayor must go, and groups of as many as twenty must be escorted by the secretary of the municipal political and legal affairs commission or the deputy mayor.Footnote 16 It is obvious that the use of coercive power in handling irregular petitions places a great burden on local officials.

One reason cadres tend to use hard measures rather than soft ones during special times is that they are influenced by the CCP's performance evaluation system.Footnote 17 It is particularly important for the authorities to maintain social stability during important government meetings and holiday periods; but unfortunately for them, those occasions are popular with irregular petitioners. Petitioners believe that they have a better chance of bringing their grievances to the attention of higher-level leaders at these times, and the top leaders will be more willing to solve their problems in order to bring their protests to an end.Footnote 18 Moreover, many petitioners are aware that during these periods, the government is more willing to make exchanges of interests to maintain social stability.Footnote 19

Faced with this surge in irregular petitions, the central government has increasingly emphasized social stability performance in its evaluation of cadres. In Province A, for example, cadres have been given a score as high as 14 for their handling of irregular petitions during special periods.Footnote 20 If an organization's score fails to reach a certain level, the responsible cadre is given a “veto” (yipiao foujue).Footnote 21 In an internal speech, Shu Xiaoqin, the director of the State Letters and Visits Bureau, said that “in any region where the issues of irregular petitions in Beijing are not properly resolved, resulting in major security problems and group incidents, the veto power system shall be legally implemented and the leading cadres concerned shall take the blame.”Footnote 22 If letters and visits work is “vetoed,” the leadership cadres will be ineligible for promotion that year, and all the awards and promotions granted to public officials in all departments related to social stability and letters and visits (the political and legal affairs commission, the public security bureau, the letters and visits bureau, etc.) will be canceled.Footnote 23 In other words, during special times, the effective handling of irregular petitions becomes the foremost consideration for the authorities, so cadres will tend to opt for hard measures despite the high costs involved.

DEALING WITH PETITIONS IN NORMAL AND SPECIAL CIRCUMSTANCES: THE EXAMPLE OF PROVINCE A AND CITY T

In normal circumstances, the handling of irregular petitions is the direct responsibility of cadres working in the letters and visits system, whereas in special circumstances, this task is transferred to the political and legal system. We shall illustrate this by describing what happens in Province A and City T.

Although the CCP has stipulated that the Party secretary at each level of government is the person responsible for letters and visits work, Party secretaries do not personally handle irregular petitions. The rules in Province A are as follows: “The leaders of the Party committee and the government at each level are the first persons in charge, … each letters and visits joint office (xinfang lianxi ban) acts as a coordinating unit that solves the problem of entering Beijing to make irregular petitions.”Footnote 24 The “letters and visits joint office” mentioned in this document is the body that actually deals with irregular petitions.Footnote 25 For example, Province A's letters and visits joint office is located in the province's Beijing offices. The office has no fixed personnel but is staffed by a succession of cadres seconded from relevant departments in Province A for several weeks at a time. In normal circumstances, the office employs six to eight members of staff; in special circumstances, this number increases to between 30 and 50, primarily drawn from Province A's politics and law departments.Footnote 26

The personnel in this office who are responsible for handling irregular petitions are under unified direction and management. In normal times, one of the deputy directors of the letters and visits bureau (who holds the concurrent post of deputy director of Province A's Beijing offices zhujing ban) is responsible for day-to-day work. Other staff are drawn from the provincial political and legal affairs commission, the public security department, the letters and visits bureau, the courts, the province's Beijing offices, and the railway administration. Therefore, in normal circumstances, the joint office is run by the provincial letters and visits bureau which uses “soft” tricks to persuade irregular petitioners to leave Beijing and return to their homes in Province A.Footnote 27

During special times, the joint office establishes a “working team of the provincial joint conference in Beijing for persuading [petitioners] to return” (sheng lianxi huiyi zhujing quanfan gongzuozu, hereafter referred to as the working team) to handle irregular petitions.Footnote 28 Province A's working team is led by the secretary of the province's political and legal affairs commission. There are six deputy team leaders: the director of the letters and visits bureau, the deputy secretary of the provincial committee, the deputy secretary of the provincial government, the head of the office of the provincial working team for the maintenance of stability, the deputy chief of the provincial public security department, and the director of Province A's Beijing offices. The working team's primary duties are to give irregular petitioners in Beijing from Province A notice to leave within a limited time and to repatriate and detain them (“hard” measures) if they are arrested by the central authorities.Footnote 29

We shall describe the circumstances in City T, which is under the jurisdiction of Province A, to illustrate what happens below the provincial level. In line with the principle of “corresponding management” (duikou guanli), both the Province A letters and visits joint office and the working team have offices in City T. Figure 2 shows how the provincial joint office and its working team guide (zhidao) their counterparts at city level. These two city units are nominally led (lingdao) by the Party secretary of City T, according to the basic principle that the Party secretary is responsible for letters and visits work. However, the work of dealing with irregular petitions is actually managed by the director of City T's letters and visits bureau in normal times and the secretary of the political and legal affairs commission during more sensitive “special” periods, just as it is at provincial level. The composition of the City T letters and visits joint office and its working team, which mirrors that of Province A's joint office and working team, is shown below.

Figure 2 Mechanism for Handling Irregular Petitions

From Figure 2, it can be seen that Province A has different modes of operation for handling irregular petitions in normal and special times. In normal times, the work is led by the letters and visits bureau (under the direct responsibility of the bureau's deputy director), while in special times it is led by the province's political and legal affairs commission (under the direct responsibility of the commission's secretary). When the lead unit is the letters and visits bureau, irregular petitions are dealt with using soft tricks; if the political and legal affairs commission is in charge, hard measures are more likely to be employed. The reasons for this include factors such as the rank of the directly responsible persons, department budgets, and clarity regarding the Party's indicators for assessing department performance.

The foremost factor is the rank of the directly responsible person. In normal times, the work is overseen by the deputy director of the letters and visits bureau who holds a relatively low-level position, and this makes the use of hard measures difficult. Hard measures, such as arrest and detention, require the involvement of law-enforcement officers from the public security bureau. However, the director of the letters and visits bureau ranks below the director of the public security bureau, while the deputy director, who in normal times is directly responsible for irregular petitions, ranks even lower. For this reason, the letters and visits bureau can only liaise with the public security bureau or request its assistance.Footnote 30 Conversely, during special times, the person directly responsible for irregular petitions is the secretary of the political and legal affairs commission, who holds a more powerful position. This official is always a member of the Party's standing committee and directly manages the public security department, giving him/her the authority to mobilize public security officers and use hard measures at any time.

Another reason letters and visits bureaus are unable to use hard measures is that they have very much smaller budgets than political and legal affairs commissions. These commissions include subordinate organizations like the office of the leading team for maintenance of stability work (weihu wending gongzuo lingdao xiaozu bangongshi), the office of the committee for the comprehensive governance of social security (shehui zhian zonghe zhili weiyuanhui bangongshi), and other such organizations, all of which have enormous budgets.Footnote 31 The use of hard measures not only involves mobilizing personnel but also a great deal of expensive administrative work.

The final factor is the specific indicators for assessing these various departments. The CCP's assessment indicators for political and legal affairs commissions are more specific than those for the letters and visits bureaus, so the former must use hard measures to achieve their assessment requirements. The primary responsibility of letters and visits bureaus is to pass cases on to the relevant departments; they have no specific authority to deal directly with the issues involved. Hence there are few concrete indicators against which these bureaus’ performance can be assessed. It is no wonder, therefore, that letters and visits bureaus sometimes appear to be lackadaisical. Since the political and legal affairs commissions have relatively clear assessment indicators (primarily, a reduction in the number of irregular petitioners) they are incentivized to use hard measures in order to perform well in their assessments.Footnote 32

EVIDENCE FOR A TEMPORALLY DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSE: THE EXAMPLE OF THE HANDLING OF IRREGULAR PETITIONS

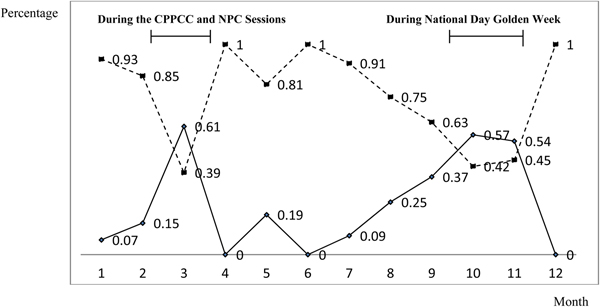

As we discussed above, the local officials use both hard and soft tricks in handling irregular petitions. We hold that, in line with the principle of the temporally differentiated response, hard measures that involve exerting the coercive power of the state are only used for short periods, while for most of the time, soft tricks are employed. This inference needs to be supported by further empirical evidence. In our case study, we use statistics concerning citizens of City T who went to Beijing to present irregular petitions. The most popular topic of the irregular petitions was unjust land acquisitions and house demolitions, followed by unjust court decisions, land disputes, and requests for increases in salary or pension.Footnote 33 The statistical data on irregular petitions are presented in Table 1 of the Appendix. The ratios of soft to hard measures used in handling irregular petitions are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Statistical Data on City T's Measures for Handling Irregular Petitions (2014–2016)

The data displayed in Figure 3 demonstrate that the handling of irregular petitions displays characteristics of the temporally differentiated response. First, during normal times, the ratio of soft tricks to hard measures is higher. Under these circumstances, coercive measures are only used against those irregular petitioners who are clearly breaking the law, such as those causing disruption or disturbances.Footnote 34 In abnormal times, hard measures are favored above soft tricks. These politically sensitive so-called special times include March (when the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference [CPPCC] and National People's Congress [NPC] are in session) and October–November (during the National Day “golden week” holiday period). It is also apparent from Figure 3 that more irregular petitioning takes place during these special periods. That is another reason why cadres seek to handle petitions more efficaciously at those times.

We reiterate that the CCP adopts a carrot and stick approach when handling irregular petitions. However, during normal and special times, the ratio of soft tricks to hard measures is influenced by cost and the cadre evaluation system. For instance, in March, when the CPPCC and NPC are in session, the CCP adopts hard measures in 61 percent of irregular petition cases, while for the rest (39 percent) it adopts a soft approach (see Figure 3). In other words, both these approaches are used all of the time. It is only the ratio of hard to soft that varies in normal and special times.

THE TRICKS INVOLVED IN SOFT STRATEGIES

The most common methods used by local officials to exercise their infrastructural power against irregular petitioners are buying-off, emotional buying-off, and persuasion by relatives and friends.

Buying off petitioners is referred to within the Party as “solving the people's internal conflicts with the people's currency.” Prominent repeat irregular petitioners are often offered cash in return for abandoning their petitions,Footnote 35 and this has become standard practice among local governments. Rather than seeking fundamental solutions to petitioners’ problems, local cadres will even use trickery or other forms of compensation to persuade irregular petitioners to give up their cause (Lee and Zhang Reference Lee and Zhang2013). During our interviews for this study, we discovered that in addition to cash payments, local governments also build houses or arrange employment for petitioners in exchange for them abandoning their irregular petitions. For example, in 2011, Petitioner S4 in City T made his first trip to Beijing to protest having received insufficient compensation for the demolition of his property and acquisition of his land.Footnote 36 By October 2017, he had made a total of 27 such trips to the capital. To prevent him from making any further journeys to Beijing, local cadres began taking S4 on trips elsewhere or sometimes directly handing over cash during special periods. For example, during the CCP's nineteenth National Congress, he was dissuaded from petitioning in Beijing after receiving a cash payment of RMB2,000.Footnote 37

As previously stated, many citizens who make irregular petitions during normal times can negotiate with or threaten local governments in order to obtain benefits. However, the benefits they receive are not necessarily related to the problems they are petitioning about. Petitioner S7 of City T is a healthy 50-year-old former soldier, but his petitions are not entirely honest. In 2013, he started petitioning in Beijing, demanding that the government provide him with a hardship allowance and a minimum living allowance, as well as giving him money to build a house. In an effort to stop these activities, his local township government went through various channels to provide him with a disabled veterans allowance of RMB300 per month and a RMB18,000 grant towards building a new house. This was not enough to put a stop to S7's irregular petitioning. This is a clear example of how some individuals use irregular petitions to force local governments to provide them with personal benefits.Footnote 38

In one example of an emotional buyoff, Petitioner S5's township government in City T helped him buy a coffin for his dead mother and bought medical insurance for his father. On the birth of S5's child, the secretary of the township Party committee went in person to the hospital and gave the family an envelope of cash. S5 said, “If I continue to petition, I will feel badly for the township Party committee secretary. But he is still unable to resolve the problem I am petitioning about, and this makes things very difficult for me. So now I only agree to quit if the township Party committee secretary calls and asks me to.”Footnote 39

Many petitioners’ problems cannot be solved by the government, but they still use the threat of irregular petitions to force the government to act. Petitioner S8 in City T began making irregular petitions in 2014 claiming that his wife had lost a lot of money through illegal lotteries. S8 attributed these losses to the local government's failure to enforce the law, and he demanded RMB200,000 in compensation. Local cadres believe there is no basis to his claims and that he is suffering from a mental disorder. However, after S8 had made two trips to Beijing to petition, the local government not only raised RMB54,000 toward his child's leukemia treatment but also arranged for treatment at municipal hospitals. S8 believes that this assistance may have been the fruit of his petitioning activities. However, during the CCP's nineteenth National Congress in October 2017, S8 ignored the remonstrations of the local government and went to Beijing to petition. He was detained by the public security forces for 10 days.Footnote 40

Lastly, cadres try to stop petitioners by working on their families and friends.Footnote 41 For example, local governments employ “collective punishment” measures (lianzuofa) against petitioners’ friends and family members who work in government agencies or public institutions, so government employees will make great efforts to stop their associates from petitioning.Footnote 42 Petitioner S6 from City T had a dispute with a company over a debt issue. He was dissatisfied with the court decision, so in 2013 he went to Beijing to petition the government. Since S6's problem involved a dispute between an individual and a company, the local government had no jurisdiction over it. However, S6's irregular petitions were a big headache for the local government, so when in 2016, Z, the newly appointed secretary of the township Party committee, learned that one of S6's relatives worked in a certain government department in the county and that his son was a university student, Z mobilized these relatives to persuade S6 to stop causing problems. He also contacted a lawyer on S6's behalf to help him file a lawsuit against the company. S6 consequently stopped petitioning and agreed to seek redress through the courts.Footnote 43

Another example is Petitioner S9 of City T. He believed that he had been inadequately compensated for the loss of his land, so in 2015, he petitioned in Beijing, asking the government to return his land. His behavior caused great problems for his local government. Although S9 had a signed document promising to transfer the land, it could not be returned because a property developer had already built houses on it. The secretary of his township Party committee learned that K, S9's elementary school classmate, was a cadre in the township, so by warning K that this would affect his performance evaluation, he made K responsible for persuading S9. K tried various ways to dissuade S9 from making irregular petitions. For example, during major holidays, K would take S9 gifts of cigarettes and alcohol to strengthen their friendship. In addition, he also tried to get S9's child transferred to the best junior high school in the county. Through these personal interactions, he persuaded S9 to give up his irregular petitions.Footnote 44

HOW HARD MEASURES ARE IMPLEMENTED

The local officials exercise their authoritarian power over irregular petitions in three ways: by preventing travel to Beijing, forced repatriation, and detention. Details of all irregular petitioners are held by the public security department. Those who have petitioned on more than two occasions are placed on a list of petitioners marked down for special monitoring. There are several methods that local officials use during sensitive times to make it difficult for these petitioners to leave their hometowns. For example, they are not allowed to buy train or airplane tickets,Footnote 45 and if they try to travel to the capital by car they are turned back at the highway checkpoint. If they do manage to sneak into Beijing, hotel staff are required to report their presence to the authorities who will have them removed.Footnote 46

Another method is forced repatriation. Petitioners who persist in irregular petitioning will be forcibly returned home by the public security authorities. When Petitioner S2 of City T took his protest over a court decision to Tiananmen Square on March 8, 2016 (when the CPPCC and NPC were in session), he was immediately taken by the police to the letters and visits bureau's reception center in Majialou. A three-person working team was dispatched from City T to collect him from Majialou, but S2 refused to cooperate with them, feeling that he had not had an adequate opportunity to air his grievance. When he tried to escape and return to Tiananmen Square, the working team dispatched two police officers from City T to forcibly escort S2 to a train and take him back home, where he was turned over to the township government.Footnote 47

The ultimate sanction is detention or imprisonment. Persistent petitioners, ringleaders, or those who cause a disturbance are detained. For example, Petitioner S3, who was subject to special monitoring, ignored the admonitions of staff in charge of maintaining stability and insisted on travelling to Beijing during the CCP's 19th National Congress. He was intercepted by personnel from City T's Beijing office and turned over to the public security authority, where he was detained for 10 days on charges of provoking a disturbance (causing trouble and creating serious chaos in public areas).Footnote 48

Petitioners who have previously been detained but who persist in petitioning and have a seriously negative influence are turned over to the courts and sentenced to terms of between six months’ and three years’ imprisonment. For example, Petitioner S10, a serial irregular petitioner, had been detained by the public security bureau of County T on three occasions, but he still refused to give up. He caused a disturbance in the vicinity of Zhongnanhai on five occasions between August 2015 and January 2016. He scattered leaflets in front of the Xinhua Gate of Zhongnanhai, which were picked up and read by passersby. The Party considered that this petitioner had seriously disturbed public order, and in April 2016, the People's Court of County L in City T charged him with provoking a disturbance and he was sentenced to two years in prison.Footnote 49

CONCLUSION: THE LOGIC OF THE TEMPORALLY DIFFERENTIATED RESPONSE AND THE MAINTENANCE OF SOCIAL STABILITY

This paper uses Province A and City T as examples in a discussion of the CCP's procedures for handling irregular petitions and the logic behind them. We have noted that both “carrots” and “sticks” have been used for this purpose. The carrots, or “soft” tricks, include cash buyoffs, emotional buyoffs, and persuasion by friends and family. The “hard” measures range from prohibiting petitioners from travelling to Beijing to forced repatriation and detention. During normal times, soft tricks are preferred, and these are the responsibility of the letters and visits joint office of each region, overseen by the deputy director of the letters and visits bureau. Hard measures are more commonly used during special periods, such as while important national conferences are in session and during public holidays, and they are implemented by the “working team of the provincial joint conference in Beijing for persuading [petitioners] to return” (working team) and overseen by the secretary of the political and legal affairs commission.

The carrot and stick approaches reflect the two types of social control strategies that the local officials exercise in handling irregular petitions. However, the ratio of hard to soft strategies used by the CCP varies during normal and special times, exhibiting a type of temporally differentiated response. During normal times, cadres use soft tricks to handle irregular petitions because of their lower political and monetary cost. During special periods, such as during important political meetings and public holidays, cadres tend to opt for hard measures, so they can obtain high scores for maintaining stability in their annual evaluations. In other words, hard measures, though effective in maintaining stability, are too costly to use all the time. This temporally differentiated response mode of operation reflects the Party bureaucracy's inability to use one long-term universal principle in handling irregular petitions because of limitations on its monopoly on power and ability to close off information.Footnote 50

Finally, although this temporally differentiated response can remove the threats posed by the aggrieved in the short term, it does nothing to resolve the underlying sources of social instability. Using letters and visits as an example, it may be that the ossification of the political system and the lack of an independent system of supervision is the cause of resentment among citizens. Even though hard measures are effective in maintaining social stability during special periods, these measures do nothing to protect petitioners’ rights and interests. In other words, the Party's measures for maintaining stability in recent years are no more than a series of social control tricks that have had numerous side effects, such as encouraging people to petition for personal profit. Many new social problems have arisen out of the Party's efforts to maintain social stability (Shambaugh Reference Shambaugh2008; Pei Reference Pei2006). The CCP's regime continues to survive, but the social control process is fraught with difficulties and it is accompanied by many uncertain factors that undermine social stability.

APPENDIX

Table 1 Irregular Petitioning in Beijing by Citizens of City T (2014–2016)