It was the early years of the 1980s, and the South African band Juluka was on the wrong side of the law. Their music was banned from the airwaves, so they had to tour to gain audiences (Baines Reference Baines and Olwage2008, p. 107). Yet touring was not a simple prospect: they were restricted from performing in public venues, and travelling to outlying South African townships to perform meant breaking the law for half the band's members. When in rural areas, the band could finish about eighty percent of their performances without hindrance, but the other twenty percent saw the police using dogs and tear gas, and even bursting onto the stage carrying shotguns to declare the show over (Clegg Reference Clegg and Bambury2017; Clegg and Drewett Reference Clegg, Drewett, Drewett and Cloonan2006, p. 130). How did the members of Juluka run afoul of what they called ‘the wrong arm of the law’ (Ngcobo Reference Ngcobo1982, p. 5)? They did so by presenting a potent challenge to apartheid ideology, in no small part by creating music whose artistic richness belies the principles of cultural segregation which the regime sought to uphold. To demonstrate this, this essay closely analyses compositional features in three songs by Juluka, showing how the band creatively combined Zulu and Western musical idioms to fashion a musical world where the two cultures flourishingly coexist.

Preliminaries

The apartheid regime's antagonist treatment of Juluka was not a reaction to any provocative activism. From the early 1970s onward the government banned albums on the grounds of indecency, blasphemy, disturbing peace, threatening the state and more (Drewett Reference Drewett2005, p. 55; Byerly Reference Byerly1998, p. 14). As a result, the members of Juluka addressed politics cautiously and did not mention apartheid. Yet their very existence as a group was a challenge to the apartheid regime of racial segregation, for half the band's members were white and the other half Zulu. Indeed, they did not need to criticise apartheid with words, for they embodied such a criticism: as Johnny Clegg, one of the co-founders, recounted, ‘Juluka is the band that said on stage: “Something else is possible”. That's all it said: “Something else is possible”’ (Clegg Reference Clegg and Bambury2017).

Juluka's origins lie in a transcultural friendship formed by Sipho Mchunu and Clegg. Mchunu (b. 1951) came from a rural Zulu family and was entirely unschooled, whereas Clegg (1953–2019) was born in Britain to white parents and for a time lectured in anthropology at a South African university. The two met in Johannesburg as teenagers, presumably at one of the migrant worker hotels Clegg surreptitiously visited to learn from Zulu dancers and musicians. They went on to form first a duo (called ‘Sipho and Johnny’) and then a band which they named Juluka, from the Zulu word for sweat (Meintjes Reference Meintjes2017, pp. 155–6).Footnote 1 While Juluka's embodiment of interracial cooperation was a very visible contradiction of the apartheid system, it was not the only reason why South African authorities repressed them. Like other South African ‘activist-performers’ (Eyerman and Jamison Reference Eyerman and Jamison1998, pp. 164–5), the members of Juluka mediated in a variety of ways the cultures which apartheid attempted to keep separate (Byerly Reference Byerly1998, pp. 1, 23–28). One approach was linguistic, as many of Juluka's songs use both English and Zulu lyrics. This combination of languages went against apartheid legislations seeking to keep languages ‘pure’, and it was consequently used as justification for the censorship of their first single, ‘Woza Friday’ (Clegg and Drewett Reference Clegg, Drewett, Drewett and Cloonan2006, p. 128). Another involved the band's live performances, where they sought to educate white audiences about the stories their songs told and the Zulu war dances they incorporated into performances. Even fans who only saw the band through their promotional material and albums’ cover art still encountered that cultural mediation through the band's costumes, which prominently mixed Zulu and Western styles of dress.Footnote 2

Of Juluka's many forms of cultural mediation, this essay focuses on the musical. Clegg himself has called explicit attention to this feature of their work: on his website's bio section, Clegg wrote that he ‘worked on the concept of blending English lyrics and Western melodies with Zulu musical structures’ with his songwriting partner, Mchunu (https://www.johnnyclegg.com/biog.html, accessed 2 March 2021). Despite this, scholarly treatments of Juluka have largely neglected analysing how these transcultural blendings are accomplished.Footnote 3 Perhaps the most extended discussion of them, by Christopher Ballantine, is rather dismissive:

From the start the band's musical integrations were awkwardly worked. Certainly, symbols for ‘white’ and ‘black’ met in the songs’ own interiors – but typically as binary, and often unequal, oppositions: ‘white’ represented largely by an English folk-rock style derived from the 1960s, which carried the song's narrative, and ‘black’ virtually relegated to the choruses. The lyrics addressed topics relevant to the anti-apartheid struggle, but commonly in two languages (English and Zulu) split along the same lines. (Ballantine Reference Ballantine2004, 109)

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ballantine's hearing of Juluka's musical integrations as superficial is based on a listening experience that does not attend carefully to these songs’ depth of artistry and ingenuity. As will be shown in this article, paying closer attention to their songs reveals that they exhibited a far more creative interplay of musical styles than Ballantine acknowledges.

The musical analyses which anchor the present article substantiate this claim. They attend to the blending of musical elements – textural, melodic, lyrical, harmonic, rhythmic and more – that symbolise ‘white’ and ‘black’. In their catalogue of 70-odd commercially released songs, Juluka engage with a wide range of genres which signify ‘white’ and ‘black’, of which the most prominent are Western folk and rock music, and Zulu mbaqanga and maskanda music. The three songs selected for analysis were chosen in part because they draw especially on maskanda,Footnote 4 a musical style whose harmonic and rhythmic characteristics are more readily distinguishable from Western styles than those of mbaqanga.

Maskanda music arose around the turn of the twentieth century among young Zulu men who migrated between their homes in rural South Africa and the centres of economic opportunity, such as mines and cities (Olsen Reference Olsen2014, pp. 20–25).Footnote 5 In its original form, as preserved in recordings from the 1950s and earlier, maskanda featured a solo singer accompanying himself, most typically with a strummed guitar.Footnote 6 In the following decades, however, a new style of guitar performance came to predominate, largely through the influence of the recordings of the maskanda icon Phuzushukela, the stage name of John Bengu (Olsen Reference Olsen2014, pp. 24–5, 32–3). In this style of finger-picking, known as ukupika, guitarists use plectrums on their thumbs and forefingers to create two (or occasionally even three) simultaneous melodic lines (Collins Reference Collins2006/2007, pp. 3–4). The resulting polyphonic effect is a hallmark of maskanda songs.

Starting in the early 1970s, producers at the South African Broadcasting Corporation ceased to record solo maskandi, as performers of maskanda are called, so the musicians formed accompanying groups (Davies Reference Davies1994, p. 133). The resulting ensemble music still emphasised the guitar, however, and did so most prominently in the songs’ introductions, which normally feature unaccompanied guitar. This introduction, called the isihlabo, is unmetred, and it serves to lay out the harmonic material for the rest of the song. Once the isihlabo concludes, the guitar establishes a new ‘melodic-rhythmic pattern’ which undergirds what follows (Collins Reference Collins2006/2007, p. 4). Above it, the singer initiates a call-and-response texture known as the ukubiza nokusabela (Titus Reference Titus2013, p. 305).Footnote 7 The responses to the soloist's calls may be provided by either one of the guitar lines or back-up singers in maskanda groups; in either case, they characteristically both enter after and overlap with the soloist's calls, and their points of melodic closure do not align (Titus Reference Titus2013, pp. 295–8).

The harmonic organisation of maskanda music varies across its subtypes. According to Barbara Titus, the isiShameni subtype ‘is quasi-diatonic in applying an ostinato progression of I–IV–V–I, also often heard in the more urban mbaqanga and isicathamiya genres’ (Titus Reference Titus2013, 291). More significant for this study is the isiZulu subtype, which harkens back to Zulu bow songs. In these, as David Rycroft (Reference Rycroft1975/1976) has detailed, a normally female singer accompanies herself by percussing the single, undivided string of the ugubhu, a bow which is 1.5–2 m long and is attached to a gourd resonator. Performers on this seemingly simple instrument can produce complex musical effects: by pinching the string, the performer can produce a second pitch, a semitone higher than that of the open string, and by shifting the position of the resonator against the body, the performer selectively amplifies harmonics of each fundamental in order to create a secondary melody (pp. 58–62). Other bow songs were performed on the umakhweyana, a divided bow, which is reputed to have been imported from Mozambique (p. 58). This instrument's string yields two fundamentals a whole tone apart, and pinching the higher string segment can produce a third fundamental pitch a semitone higher (Davies Reference Davies1994, p. 132). Maskandi who performed in the isiZulu style distilled these acoustic phenomena to their harmonic and melodic principles: two triads, a semitone or whole tone apart, and six-note scale. (Maskandi, however, frequently employ minor triads, which were unavailable on the ugubhu; Davies Reference Davies1994, p. 132.) Rycroft has noted that in ugubhu songs, either the lower or higher fundamental pitch may predominate (Rycroft Reference Rycroft1975/1976, pp. 65–6). Secondary literature on maskanda music has not focused on how composer-performers deploy these harmonic materials in their songs, but I have observed in isiZulu music a similar propensity to emphasise either the lower or higher fundamental pitch.

Before proceeding to the analyses of compositional decisions, it is important to address the matter of compositional attribution. Louise Meintjes explains that ‘from a young age Clegg came to embody Zulu aesthetics and affective warriordom by apprenticing himself to musicians and dancers’ (Meintjes Reference Meintjes2017, p. 155). Clegg's process of learning Zulu culture via personal contact muddles such attributions, particularly when considering elements of Zulu musical practice. The majority of songs in Juluka's catalogue were published under Clegg's name (the remainder are attributed solely to Mchunu or to both jointly).Footnote 8 Yet given Clegg's status as someone seeking entrance into Zulu culture, it is unlikely that he dictated all stylistic details to the Zulu members of the band, or that they made no contributions of their own to their performances. Furthermore, the bulk of the musical details analysed in this paper fall outside of the bounds of the compositional details for which the composers could legally claim copyright, and instead are characteristics of the performance, which is credited to the band.Footnote 9 Additionally, the band's later reception further complicates attributions to Clegg alone. After Juluka disbanded and Mchunu returned to farming in 1985, Clegg formed another group, which recorded under the name ‘Johnny Clegg and Savuka’.Footnote 10 As a result, some internet resources refer to the earlier band as ‘Johnny Clegg and Juluka’, and even ‘Johnny Clegg and Juluka [feat. Sipho Mchunu]’.Footnote 11 This suggestion of ‘Clegg and supporting musicians’ is clearly a distortion of the band's self-presentation as a partnership among equals, since all of its albums were issued under the name ‘Juluka’ and featured Clegg and Mchunu together on the cover illustrations. Consequently, I will attribute compositional decisions to Juluka as a group in order both to reflect Clegg's collaborative approach to learning Zulu culture and to avoid minimising the significance of the other band members.

‘December African Rain’

When Ballantine wrote that Juluka's symbols for ‘white’ were ‘represented largely by an English folk-rock style’ and that symbols for ‘black’ were virtually relegated to the choruses (Reference Ballantine2004, p. 109), he may have been thinking of a song such as ‘December African Rain’, from Juluka's 1984 album Work for All. In this song, Clegg sings an image-laden narrative through the verse and pre-chorus, while the chorus includes ngoma-signifying ‘vocable motives with strong backbeat pickups sung in repeated cycles by the backing vocalists’ of the sort that were frequently used by Juluka and Savuka (Meintjes Reference Meintjes2017, pp. 157, 160–1).

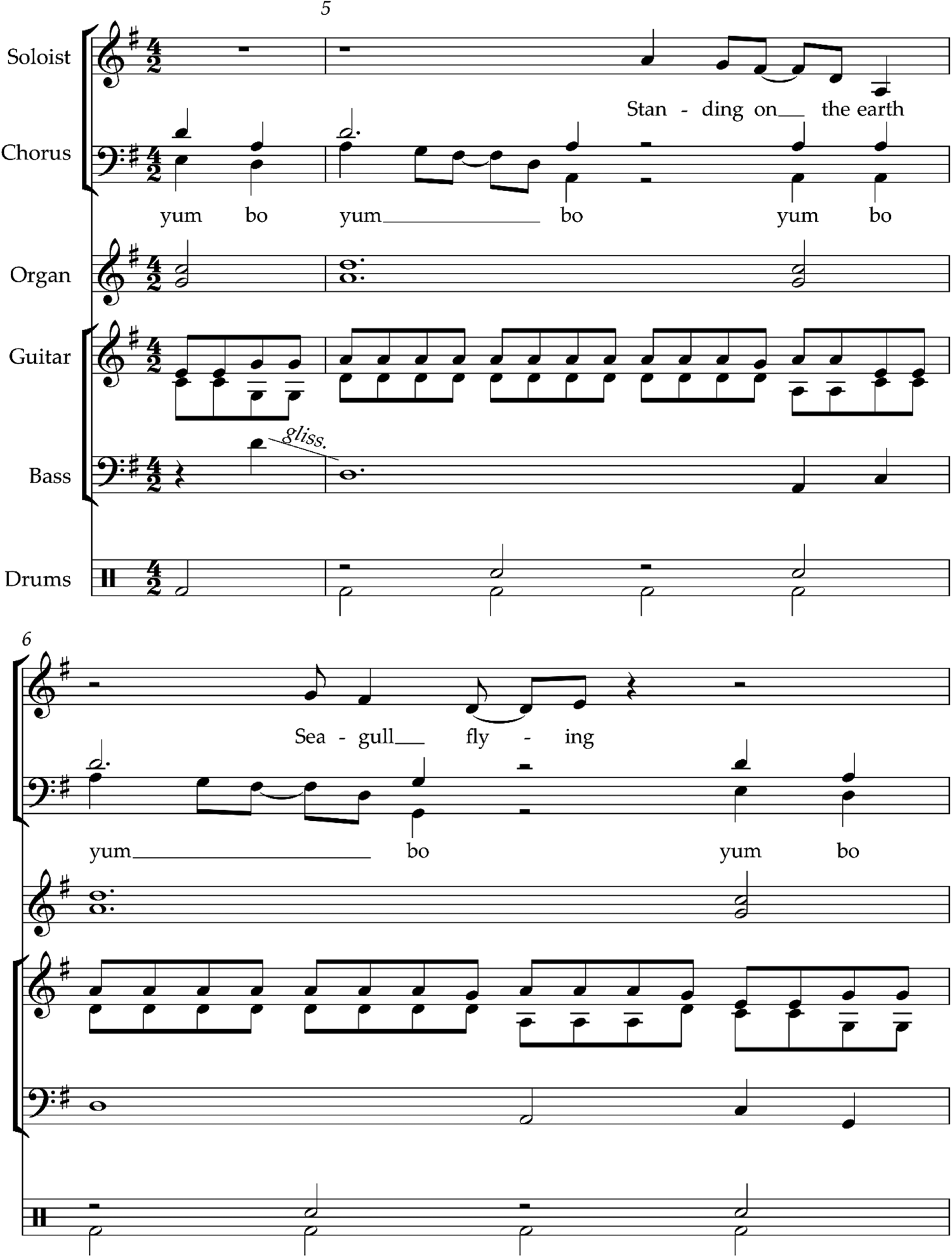

Upon closer inspection, however, the picture becomes much richer. Consider the backing vocalists: in addition to their vocables with ‘strong backbeat pickups’ in the chorus, they also contribute a prominent strong-beat-emphasising vocable motive to the texture which underlies the intro, verses and outro (see Example 1 for the beginning of the first verse).Footnote 12 The song starts with the guitar and drums establishing a repeated melodic-rhythmic pattern, and beginning in m. 3 the two-part chorus initiates a melodic descent every four beats and exactly repeats its melody every eight beats. Against this stable foundation the soloist enters partway through m. 5 with a call that echoes the lower chorus's melodic descent. The resulting call-and-response texture exhibits a non-alignment of calls and responses (with respect to both their entrances and points of arrival) that Rycroft describes as being paradigmatic for traditional music of both the Zulu people and their relatives, the Xhosa and Swazi (Rycroft Reference Rycroft1977, p. 222). In this case, however, both the soloist and chorus begin their eight-beat-long melodies in the same measure, but the soloist's temporal relationship with the chorus shifts every four beats. In the first group of four beats, the soloist enters on the third crotchet, while the chorus is silent; in the second group, he enters on the second crotchet, overlapping with the chorus's invariant rhythm.

Example 1. Juluka, “December African Rain,” beginning of verse.

The hint of rhythmic instability that arises from the soloist's shifting relationship with the chorus starts to become unmistakable in m. 11. There the soloist departs from the repeated two-measure phrase with a one-measure extension that combines the melodic descent of the phrase's first measure with the rhythmic disposition of the second measure. At m. 12 the preceding music is disrupted by an abrupt change of texture and metre (see Example 2). As the chorus falls silent, the vocal texture shifts from call-and-response to a soloist-dominated texture in a lower tessitura. Simultaneously, the synthesiser drops out and the guitarist moves from playing dyads to a more arpeggiated texture. The metre changes even more notably. Until this point, the song has proceeded at a moderate pace, with duple groupings at every level of the musical structure, with the exception of the hypermetrical extension in m. 11. At m. 12 the drummer doubles the speed of his bass- and snare-drum pattern, which imparts an intensifying ‘double-time’ feeling to the new material. At the same time, the soloist, guitarist and bass player begin to establish a much more complex metre. The metrical organisation is clearly based on an 18-beat period: the melody introduced in m. 12 returns 18 beats later, at the start of m. 15, and then the chorus section begins 18 beats after that. Within those 18 beats, however, the organisation is more ambiguous. The rhythmic profile of the first 10 beats (m. 12) is particularly complex. Against the drum-set's steady crotchet pulse, the bass and soloist initially present a dotted-crotchet pulse, but this is contradicted at the words ‘love song’ by syncopated crotchets.Footnote 13 Mm. 13–14 briefly provide a reorienting duple metre, and then the entire 18-beat cycle repeats again, with the same rhythmic profile largely preserved. ‘December African Rain’, then, involves a range of rhythmic and metric devices: shifting alignment between the call and response voices, hypermetrical extension and an unusual metre. I have not encountered these techniques in maskanda recordings, nor are they mentioned in scholarly writings on that genre. Consequently, Juluka's employment of these techniques appears to be an intentional decision to explore the artistic possibilities of joining Western compositional techniques together with maskanda practices.Footnote 14

Example 2. Juluka, “December African Rain,” pre-chorus.

The formal organisation of ‘December African Rain’ is another respect in which the members of Juluka combine Western and Zulu musical ideas. The song begins by establishing a call-and-response texture, or ukubiza nokusabela, between the chorus and soloist. In a maskanda song, this call-and-response idea would usually form the basis for the rest of the piece's formal organisation; in ‘December African Rain’, by contrast, the call-and-response gives way to new material that suggests a pre-chorus and a chorus section. As we have already seen in our discussion of the 18-beat period, changes in instrumentation, vocal texture and metre all support hearing a formal division at m. 12. The proper characterisation of the new formal section may not immediately be evident, but particularly when heard in relation to the next section, m. 12's doubled speed of the drumming and the large-scale pre-dominant to dominant harmonic progression build up a sense of momentum that is typical of pre-chorus sections (Summach Reference Summach2011, §3; de Clercq Reference de Clercq2012, p. 91). The subsequent appearance in m. 18 of the chorus section is unambiguous (see Example 3): in addition to the invariance of the lyrics in mm. 18–32 (Summach Reference Summach2012, pp. 109–12) and the appearance of the song's title in the text, the music is also louder and texturally thicker than the preceding material, as is characteristic for chorus sections (de Clercq Reference de Clercq2012, pp. 40–41). The pre-chorus's pre-dominant to dominant progression also leads to a pointed emphasis on the Ionian tonic at the start of the chorus, which is another common characteristic of chorus sections in Western popular music (de Clercq Reference de Clercq2012, p. 50).

Example 3. Juluka, “December African Rain,” beginning of chorus.

With these aspects of the song's formal organisation in mind, it is difficult to accept Ballantine's assertion that ‘symbols for “black” [are] virtually relegated to the chorus’. In fact, with the exception of the backing singers’ vocables, the chorus in ‘December African Rain’ appears to be its most conventionally Western section. For instance, at the start of chorus section all of the vocalists sing simultaneously, relating as a soloist and backup singers, in contrast to the verse's sustained call-and-response texture. Or consider the instrumentation: in the chorus section the previously prominent sound of the guitar recedes into the wash of the backing instruments. While this contributes to the greater textural fullness of the chorus, it also shifts away from the emphasis on guitar that ‘distinctly flags the sound as South African in the World Music market and as a local production in the domestic [South African] market’ (Meintjes Reference Meintjes2003, p. 157). The song's harmonic schemes also support this impression: the verse's harmonic disposition in mm. 3–11 somewhat suggests an isiZulu-style alternation between fundamentals of D and C, particularly in the synthesiser. The pre-chorus and chorus, in contrast, switch to an emphatically Western tonal syntax: leading tones replace the lowered-seventh scale degree throughout, half cadences abound and there is even an applied-dominant progression at mm. 40–41. As a result, the form, instrumentation and harmonies of ‘December African Rain’ clearly gainsay Ballantine's verse–chorus associations, and the textures and rhythmic features exhibit creative intermingling of Western and Zulu musical elements. Yet this style of verse/chorus-based song with strong maskanda influences was not Juluka's only model, as we shall now see.

‘Sky People’

In 1979, some three years after Mchunu and Clegg formed Juluka, the band released its first album, Universal Men. The album's opening track, titled ‘Sky People’, proceeds in many ways as a maskanda song. For instance, the first 20 seconds of the piece are suggestive of an isihlabo introduction section (see Example 4). At the start a solo guitarist finger-picks a polyphonic texture which comprises two distinct melodic lines. The resulting music lays out the harmonic material that will govern the rest of the piece: C major and D minor triads, as is characteristic of the isiZulu subtype of maskanda. And finally, after the first 20 seconds, the end of the isihlabo is signalled by the entrance of other instruments, which establish a new ‘melodic-rhythmic pattern’, which they sustain through much of the rest of the piece.

Example 4. Juluka, “Sky People,” opening.

Yet the opening 20 seconds of ‘Sky People’ also dispense with certain features of the isihlabo, such as its solo-guitar instrumentation. Instead, the guitar is joined by a chorus of male voices, which enters half-way through the introduction. The upper voices in this chorus sing a descending melody that loosely derives from the guitar part, and the lower voices mirror the upper ones, largely at the fifth below. The introduction's metrical disposition is also noteworthy: while solo-guitar isihlabo sections are unmetred, the introduction in ‘Sky People’ is clearly metrical, presumably to facilitate the coordination of guitarist and chorus. The guitarist starts a melodic descent every four crotchet beats, and every eight beats its melodic-rhythmic pattern repeats almost identically. Underlying this seemingly simple duple metre, however, is much more rhythmic complexity. For instance, although the chorus similarly starts a melodic descent every four crotchets, they are displaced by three semiquavers from the guitar's descents. (And this is not a matter of a simple semiquaver anticipation in the chorus's descents: the final note of their melodic figure is likewise displaced by three semiquavers from the end of the guitar's pattern.) Furthermore, the chorus repeats its melodic-rhythmic pattern every eight beats, just like the guitar, but their statements are staggered by one measure, with the guitar and chorus beginning their statements in alternate measures. Beginning a song with rhythmically complex relationships of this sort lessens the music's evocation of maskanda, with its unmetred isihlabo introductions.

The rhythmic complexity of the introduction of ‘Sky People’ also extends to its harmonic rhythm, which is entirely uncoordinated with the initiations of both the guitar's melodic descent and also the chorus's. Instead, as the lowest staves of Example 4's systems indicate, the chord roots never change on downbeats: in one measure C enters on the third crotchet,Footnote 15 and in the alternate measure the harmony returns to D on the fourteenth semiquaver. This harmonic rhythm further aligns the song with maskanda music, where changes of harmony on weak beats are not uncommon, even at the level of weak semiquavers.Footnote 16 Despite the metrical weakness of the latter harmonic shift, it is reinforced by its concurrence with the last note of the guitar's higher melodic line and by the clear change of harmony in the chorus's parts.

The change of harmony on the fourteenth semiquaver of the even-numbered measures also relates to one of the song's most intriguing features. In addition to all their metrical complexity, the first 20 seconds of ‘Sky People’ are also in a state of metrical displacement from the rest of the song. The seam between the end of the would-be isihlabo and the start of the next section is unmistakable: the guitar breaks its pattern and establishes the new melodic-rhythmic pattern that it sustains for most of the song thereafter. Two measures later, the bass and drums enter, buttressing the duple metre that persists until the end. Yet this seam is irreconcilable with the duple metre established in the introduction. As Example 5 shows, the change occurs on what would be the fourteenth semiquaver in m. 8 (at the same point where the harmonic shift was expected to fall), but this moment instead becomes the downbeat of a new measure, as the entrance of the bass and drums eight beats later retrospectively confirms. Since the point of metric reinterpretation is such a weak beat in the original metre – a weak semiquaver – it is very difficult to hear any sense of metrical continuity between the introduction and the piece's continuation. Instead, one can understand the introduction's metrical disjointedness as an analogy for the isihlabo's lack of metre.

Example 5. Juluka, “Sky People,” continuation.

Two further features of the later sections of ‘Sky People’ merit discussion. First is the rhythmic character of the melodic patterns established by the instruments after m. 9. While the bass drum sets out an unmistakable crotchet pulse beginning in m. 11, the guitar, snare drum and bass line all cultivate a cross-rhythm of four dotted quavers followed by two regular quavers. Moreover, the harmonic rhythm also aligns with this cross-rhythm: the new melodic-rhythmic pattern's harmonic support shifts from D to C on the tenth semiquaver of each bar, simultaneously with the fourth dotted quaver. This sort of cross-rhythm ‘performs Zuluness’, as Meintjes (Reference Meintjes2003, p. 174 ff.) puts it, through its resemblance to the 3 + 3 + 2 rhythm that structures various Isishameni dance steps (Clegg Reference Clegg and Tracey1982, p. 11).

The other noteworthy feature is the bass's imposition of Western functional-harmony connotations onto the piece's isiZulu-based harmonic language. When the chorus begins singing its four-measure phrases in m. 14, the bass player establishes a new melodic pattern that he then varies freely. The characteristically isiZulu harmonic material of two triads with fundamentals a whole tone apart (D minor and C major triads in this song) is still plainly evident, particularly on beats one and four. Yet the bass line always includes a prominent A towards the end of beat four, despite the fact that this emphasised note is not a member of the underlying C major triad. Instead, the bass line presents a blending of harmonic implications: the addition of the non-triadic A to the C harmony suggests a tonic-dominant opposition (although a minor dominant chord, to be sure) simultaneously with the whole-tone-related fundamentals from isiZulu maskanda music.

In sum, ‘Sky People’ presents a sophisticated mediation of Western and Zulu musical patterns. The introduction's guitar figuration suggests an isihlabo section, but the characteristic lack of metre is replaced by a state of metric shiftedness. When the chorus enters and lessens the evocation of an isihlabo, their call-and-response patterns still signal Zuluness through their metrically off-set arrangement. Thereafter, the harmonic materials conform to the two-root patterns found in isiZulu songs, but the bass player consistently adds a non-triadic note that suggests Western tonic-dominant relations. In doing so, Juluka presents a musical argument that a rich aesthetic experience can result from breaching the strict cultural segregation which the apartheid regime sought to impose.

‘Scatterlings of Africa’

The final song is probably Juluka's best-known composition. ‘Scatterlings of Africa’, first released on their 1982 album Scatterlings, appeared on the soundtrack for the film Rainman and made the UK singles chart, although in an arranged form recorded by Savuka, Johnny Clegg's second band.Footnote 17 In contrast to the previous two songs examined, the lyrics of ‘Scatterlings of Africa’ directly critique the Apartheid ideology. Rather than subscribing to the dogma of an essential difference between races, the members of Juluka emphasise all of humanity's common origin in Africa and our shared journey, singing that ‘we are scatterlings of Africa, both you and I. We're on the road to Phelamanga, beneath this copper sky’. (‘Phelamanga’ is a coined word roughly meaning ‘the end of lies’.Footnote 18)

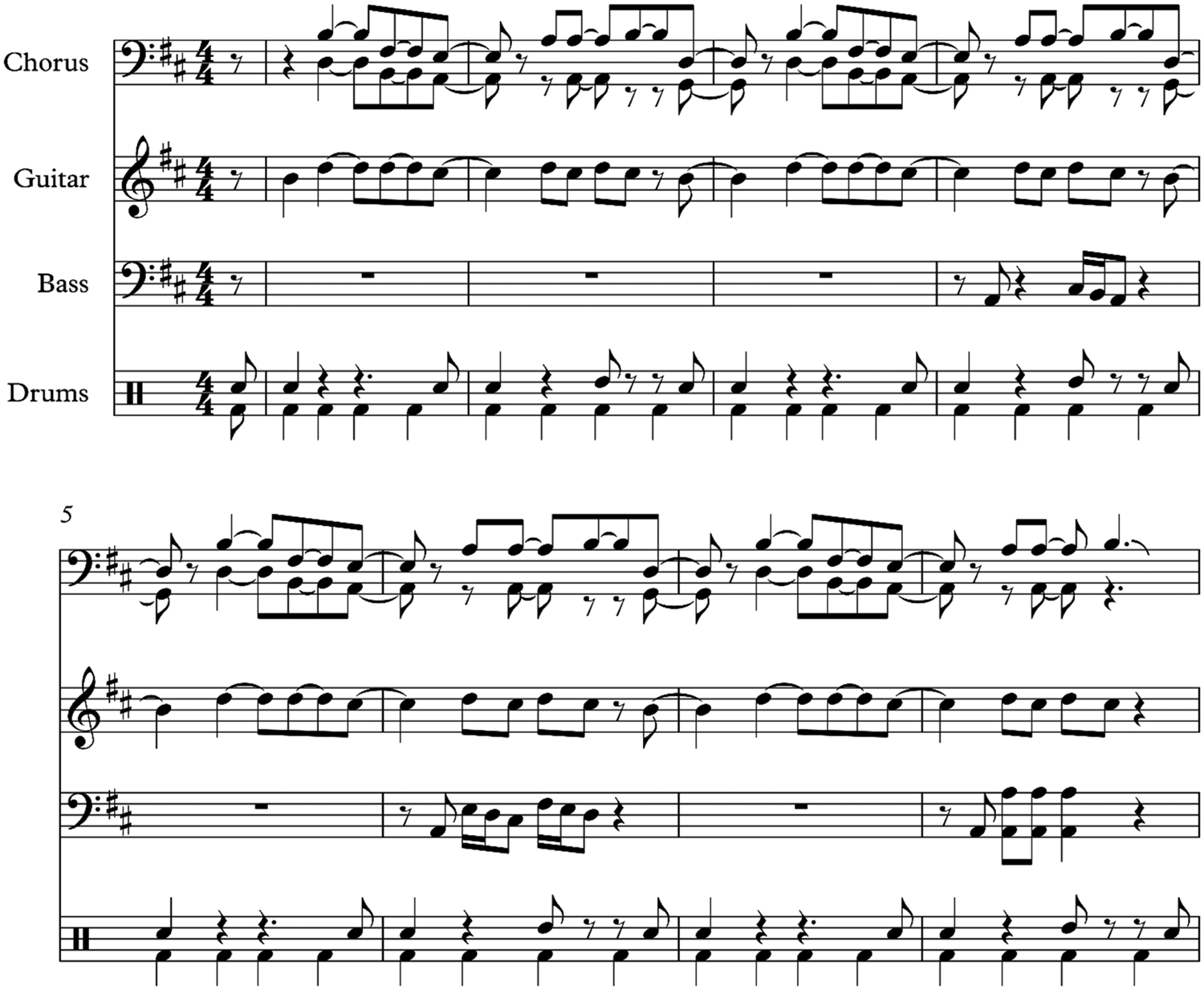

This song hews less closely to the characteristics of maskanda than the previous songs considered, but it still preserves many of their sonic signatures. Like ‘Sky People’, the song's introduction features the male chorus singing in two parts, at roughly a fifth from each other, and then a brief instrumental section (of guitar, bass, and drums) before the main vocal melody begins. And like ‘December African Rain’, the song draws upon Western tonal syntax and harmonic progressions, presents a modified verse-chorus structure and contains a significant amount of rhythmic complexity, which will be our focus.

In the introduction of ‘Scatterlings of Africa’, the bass drum begins to articulate a steady four-on-the-floor crotchet pulse, and the other instruments and singers clearly establish four-beat groupings of that pulse (Example 6). As a result, listeners are primed to hear a four-four metre, and they may well continue to hear the music that way until the last measure of the verse. Yet as the instrumental lead-in to the first verse begins in m. 9, listeners are gradually confronted with challenges to that interpretation. The guitar and bass join together to play a varying melodic figure that repeats every eight beats, and the soloist's melody also begins a new line every eight beats, as Example 7 demonstrates. Consequently, listeners hearing a four-four metre receive confirmation of that interpretation every two measures. The downbeats of the weaker four-four measures, however, are much harder to hear, since the soloist and bass player avoid playing at those moments. Instead, I prefer to hear a three-plus-five division of the eight-beat period, as shown in staff b of Example 7. In this interpretation the new mid-period division is supported by a contour accent in the vocal line and the onset of a relatively long duration in the bass part. Thereafter the bass line is entirely syncopated, but the guitar melody suggests a division of three-plus-two crotchets.

Example 6. Juluka, “Scatterlings of Africa,” opening.

Example 7. Juluka, “Scatterlings of Africa,” beginning of first verse.

Latent beneath the bass drum's crotchet pulse, however, lies yet another rhythmic stream. In fact, the guitar, bass, and soloist project a dotted-crotchet pulse through much of the eight-beat period (see staff c of Example 7). Admittedly, this pulse is not so easy to entrain, because it both conflicts with the percussion and breaks off in favour of simple crotchets for the last two beats of each period. (It does, however, become clearer in the chorus section, where the bass plays dotted crotchets at the start of nearly every measure.) This alternate pulse has implications for the song's text setting. For one, because the soloist is articulating a pulse that is not isochronous with the underlying crotchet pulse, notes that the soloist emphasises often fall on weak beats of the overall metric framework. Furthermore, melodic and rhythmic factors frequently accentuate weak syllables of the lyrics. For instance, in the text's first line, ‘Copper sun, sinking low’, the second syllables of ‘copper’ and ‘sinking’ are the highest pitches in their respective melodic contours and align with the bass drum's crotchet pulse, despite being unstressed syllables from a poetic perspective. This seeming lack of artfulness, however, is actually a hallmark of Zulu song. As Rycroft has noted, Zulu singers appear to favour ‘extreme forms of word distortion regarding syllable length and stress placement. … In song, the duration given to the longer and shorter syllables of spoken Zulu is frequently directly reversed, and stressed syllables are placed on off-beats’ (Reference Rycroft1971, 237). As a result, Juluka's decision to set the lyrics to a conflicting pulse stream was an effective way both to ensure a degree of internal coherence for the melodic line, and to align the setting of English lyrics with Zulu song practices.

Although the chorus section (see Example 8) does clarify the dotted-crotchet pulse, it further complicates the song's metric profile by shifting to a repeated pattern lasting seven crotchet beats, which the bass drum continues to articulate.Footnote 19 Curiously, Johnny Clegg did not view the seven-beat periodicity as a necessary feature of the chorus. When he re-recorded the song five years later with Savuka, an extra beat was added to the end of each seven-beat period to render a consistent duple metre.Footnote 20 I suspect that this alteration was made to support the more rock-oriented sound of Savuka. In particular, the drummer in the Savuka recording plays a conventional pattern of snare drum hits every second crotchet (offbeat) throughout, and this pattern would have become misaligned with the metre every second measure had the seven-four metre been maintained. (The drum pattern alone does not explain everything, however, since Clegg also performed the duple-metre version even when no drumming was present.Footnote 21) With Savuka, Clegg moved away from Juluka's focus on Zulu-signifying sounds towards a more pan-African style (Meintjes Reference Meintjes2017, p. 160), so it is possible that he viewed the seven-four metre as a Zulu-connoting peculiarity that was less suitable for his new band's purview.Footnote 22

Example 8. Juluka, “Scatterlings of Africa,” beginning of chorus.

The second verse of ‘Scatterlings of Africa’ exhibits additional metrical manipulations that may support the association of irregular metrical frameworks with the performance of Zuluness. Once the chorus section concludes, the instrumental lead-in from m. 9 returns, followed by new words set to a slight modification of the first verse's melody. Throughout these measures the rhythms and pulses of the first verse are maintained. The chorus section, however, does not immediately follow; instead, the second verse continues on to become twice the length of the first verse.Footnote 23 The new, second part of the second verse (Example 9) differs in notable ways from the first half. From a metrical perspective, any hint of a dotted-crotchet pulse is suppressed. Although the interiors of the eight-beat periods are still quite syncopated, the effect is of a syncopated four-four metre, rather than the more complicated three-plus-five of the verse's beginning. With respect to the lyrics, the verse's second half directly repeats its words: ‘African ideals, make the future clear’. Note that it is when Juluka invokes the implicit pan-Africanness of ‘African ideals’ that they shift from the idiosyncratic complex metrical state to a more conventional duple metre. (The verse's second half also introduces an accompanying flute, an instrument which is not strongly associated with Zulu musical culture.Footnote 24) This interpretative association of complex metre with performing Zuluness is speculative, not certain, particularly since most of Juluka's songs are in conventional duple metres, but it does offer possible insight into the metrical changes over the course of the ‘Scatterlings of Africa’ and across different performances of it.

Example 9. Juluka, “Scatterlings of Africa,” conclusion of second verse.

Conclusion

The members of Juluka worked together across lines of race and culture, and in doing so demonstrated possibilities for artistic and interpersonal richness that the apartheid regime sought to deny. Their songs present a mediation of Western and Zulu musical cultures, and, pace Ballantine, their musical integrations were far from awkwardly worked. With its methodology of closely analysing harmony, form and rhythm, this essay has demonstrated that their songs far surpass the binary, one-or-the-other oppositions of ‘white’ and ‘black’ symbols which Ballantine ascribes to them. For instance, in ‘Sky People’ and the verse of ‘December African Rain’, the harmonic organisations suggest a superimposed Western tonic-dominant relation on top of isiZulu-based pairs of chordal roots separated by a tone or semitone. Nor are the Zulu-signifying elements virtually relegated to the choruses. The verse in ‘December African Rain’ exhibits far more textural and harmonic signs of maskanda music than does its chorus, and ‘Sky People’ entirely dispenses with verse-chorus form in favour of a maskanda song structure. Finally, in ‘Scatterlings of Africa’ and ‘December African Rain’, Juluka's use of unusual time signatures, complex rhythmic patterns, and hypermetrical manipulations resemble both Western compositional practices and the rhythmic and metric patterns of Zulu ngoma dance and bow songs.

Why does it matter that Juluka's transcultural collaboration resulted in successful musical integrations? The stakes are larger than merely correcting the scholarly record, or even defending the aesthetic value of the band's music against dismissive judgement. Rather, as Byerly (Reference Byerly1998, pp. 23–6) has pointed out, the existence of bands which exhibited ‘a complete fusion of musicians, styles and languages from different backgrounds’ and whose works were ‘characterized by rich superimpositions of not merely musical components like melodies, harmonies, rhythms, and instrumentations, but also by juxtapositions of linguistic components’ was an important strategy for interracial collaboration during the democratisation process. In this light, the artistic success of Juluka's blendings of Western and Zulu musical ideas directly contributes to the potency of their artistic activism. Through their songs they demonstrated that working together across lines of imposed cultural separation creates a richer world, that ‘something else is possible’ beyond apartheid. Consequently, musical analysis of Juluka's songs not only brings to light their overlooked artistry, but also helps us to appreciate better their music's role in advocating for a more just and united world.

Acknowledgement

I would like to express my gratitude to my two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful suggestions.