Introduction

Despite its global importance and the recognition of dementia as an international public health priority, interventions to reduce stigma of dementia are a relatively new and emerging field (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019). “Stigma” refers to an attribute or characteristic which is socially discrediting and involves negative beliefs (stereotypes/prejudice), lack of knowledge (ignorance), and discriminatory behavior (discrimination) that results in unjustifiable or unequal treatment (Goffman, Reference Goffman1963; Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam, & Sartorius, Reference Thornicroft, Rose, Kassam and Sartorius2007). The stigma of dementia may detrimentally impact interactions with health care providers, health service utilization, and experiences in acute care settings, and can lead to social isolation, feelings of shame, and suicide (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019).

Over the past 10 years, a growing number of organizations have identified the increasing need for research to address stigma of dementia (Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, 2019; Centers for Disease Control, 2015). The World Health Organization (2012) created, Dementia: A public health priority which sheds light on the growing need for global action to raise awareness and reduce dementia-related stigma. Following this report, Alzheimer’s Disease International (2019) released an independent report which emphasized that dementia-related stigma often prevents people from seeking dementia diagnosis, treatment, and support.

Despite this increasing awareness, there is a paucity of research focusing on interventions to reduce stigma of dementia. Rather, researchers have focused on identifying and documenting stigmatizing attitudes among various groups of people such as nurses (Hanssen & Tran, Reference Hanssen and Tran2018); general practitioners (Gove, Downs, Vernooij-Dassen, & Small, Reference Gove, Downs, Vernooij-Dassen and Small2016; Gove, Small, Downs, & Vernooij-Dassen, Reference Gove, Small, Downs and Vernooij-Dassen2017; Low, McGrath, Swaffer, & Brodaty, Reference Low, McGrath, Swaffer and Brodaty2018); dementia care workers (Kane, Murphy, & Kelly, Reference Kane, Murphy and Kelly2018); family members (Abojabel & Werner, Reference Abojabel and Werner2019); family caregivers (Mkhonto & Hanssen, Reference Mkhonto and Hanssen2018); minority and ethnic groups (Nielsen & Waldemar, Reference Nielsen and Waldemar2016; Woo, Reference Woo2017); and the general public (Stites et al., Reference Stites, Johnson, Harkins, Sankar, Xie and Karlawish2018). A recent systematic review identified more than 50 articles reporting stigma-related attitudes towards people living with dementia (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Welter, Leverenz, Lerner, Udelson and Kanetsky2018b). Although negative attitudes of dementia are well documented, there is a dearth of knowledge on interventions to reduce dementia-related stigma.

The purpose of this review was to summarize the existing literature and identify key components of interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia. We used Corrigan and Penn’s (Reference Corrigan and Penn1999) stigma reduction framework to classify interventions into three categories: education (to dispel myths with facts and accurate information), contact (to provide interaction with persons with dementia), and protest (publicizing and speaking out against instances of prejudice or discrimination to suppress negative attitudes and challenge stereotypes of dementia). Findings from our study can inform the development of interventions to support programs, policies, and practices to reduce stigma and improve the quality of life for people with dementia.

Methods

Our study was guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s (Reference Arksey and O’Malley2005) five-stage scoping review process: (1) identifying the research question, (2) searching for relevant studies, (3) identifying studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) summarizing and reporting the results. Scoping reviews are appropriate for studying new topics that are complex in nature and have not been previously reviewed, such as interventions to reduce stigma of dementia. Scoping reviews are also useful because they provide a rigorous and transparent method for mapping and synthesizing areas of research in terms of volume, characteristics, and findings.

Research Question

Drawing on Corrigan and Penn’s (Reference Corrigan and Penn1999) stigma-reduction framework, our research questions for this scoping review included: (1) What education, contact, and protest-based interventions have been developed to reduce stigma towards people with dementia? (2) What are the key components of the different types of interventions?

Data Sources and Search Strategy

We searched seven health and social science databases including: PubMed, MEDLINE®, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). Web of Science; PsycInfo, Google Scholar, and Social Services Abstracts. Combinations of search terms included: dementia, OR Alzheimer’s disease (AD), OR Alzheimer’s, OR cognitive impairment, AND stigma, OR dementia-related stigma, OR anti-stigma, OR stigma reduction, OR negative attitudes, OR stereotypes, OR discrimination, AND actions, OR strategies, OR interventions, OR programs.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed to support the identification of relevant studies. The inclusion criteria included: (1) publication in English, (2) full text, peer-reviewed journal articles, (3) reported findings on interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia, and 4) having been published between January 2008 and January 2019. In 2008, a number of groups such as the Alzheimer’s Society (United Kingdom), Alzheimer’s Association (United States), and the Scottish government launched campaigns to increase public awareness, negate stigma, and improve knowledge of dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2012). Given these events, 2008 was selected as the starting point for this review. The exclusion criteria included: (1) articles that did not report research results (e.g., commentaries/editorials), (2) articles on describing stigma-related attitudes rather than stigma-reduction interventions, and (3) research on interventions to address cognition rather than stigma.

Screening and Study Selection

Each of the databases was searched separately by two independent reviewers in order to support reliability and rigour, and to ensure that no relevant articles were overlooked. We imported the search findings into bibliographic management software, followed by a systematic de-duplication. The two researchers independently screened the titles and abstracts of the articles based on the defined criteria. Full-text articles were assessed against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies related to article inclusion were discussed between the two reviewers.

A total of 732 citations were identified in the electronic databases, and 12 additional studies were found by hand-checking relevant reference lists. After 28 duplicates were removed, 716 articles remained. Following the title and abstract review, 682 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. After reviewing the full text of the remaining 34 articles, 13 studies were excluded for the following reasons (Figure 1): commentary or review rather than research article (Hand, Reference Hand2018; Lundquist & Ready, Reference Lundquist and Ready2015; Mukadam & Livingston, Reference Mukadam and Livingston2009; Swinnen, Reference Swinnen2012); interventions focused on addressing timely dementia diagnosis not stigma (Brooker, La Fontaine, Evans, Bray, & Saad, Reference Brooker, La Fontaine, Evans, Bray and Saad2014; Devoy & Simpson, Reference Devoy and Simpson2017; Edwards, Voss & Iliffe, Reference Edwards, Voss and Iliffe2014); interventions to address education not stigma (Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Lach, McGillick, Murphy-White, Carroll and Armstrong2014); interventions focused on the benefits for people living with dementia not on reducing stigma (Beard, Knauss, & Moyer, Reference Beard, Knauss and Moyer2009; Bienvenu & Hanna, Reference Bienvenu and Hanna2017; Greenwood, Gordon, Pavlou, & Bolton, Reference Greenwood, Gordon, Pavlou and Bolton2018; Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O’Connor, & Purves, Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O’Connor and Purves2016); and not available in the English language (Kaduszkiewicz, Rontgen, Mossakowski, & van den Bussche, Reference Kaduszkiewicz, Rontgen, Mossakowski and van den Bussche2009). After the full text review, 21 articles were included in the scoping review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study flow chart

Data Extraction and Analysis

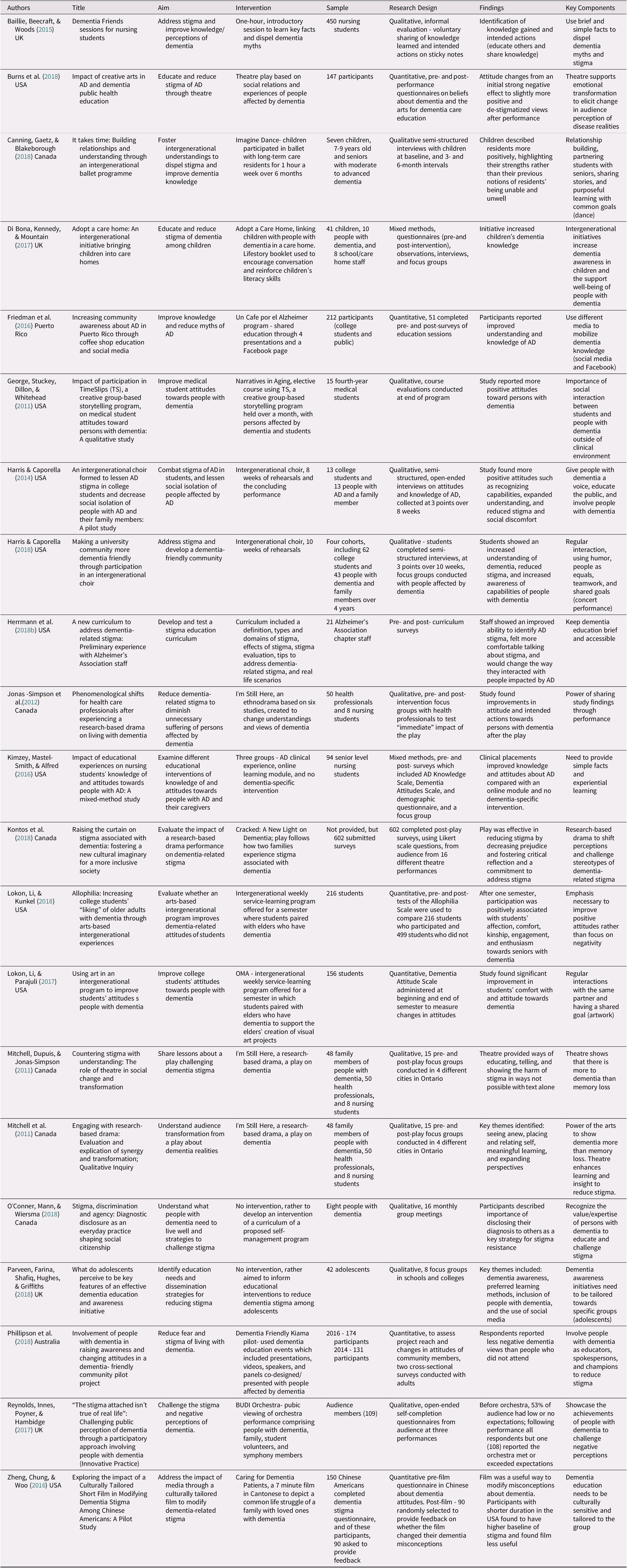

After a review of the relevant articles, the data were extracted and charted using a standardized template developed by the research team. The extracted data included the study’s aims, interventions, sample, research designs, findings, and key components (see Table 1). A preliminary pilot test was independently conducted by two of the reviewers, who extracted data from four of the included articles. Any data extraction concerns were discussed between the reviewers before they reached a final decision. Following the data extraction, the research team reviewed the data extraction tables to ensure clarity and consistency in the reporting of the data.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of included studies

Note. AD = Alzheimer’s disease

Results

Descriptive Analysis

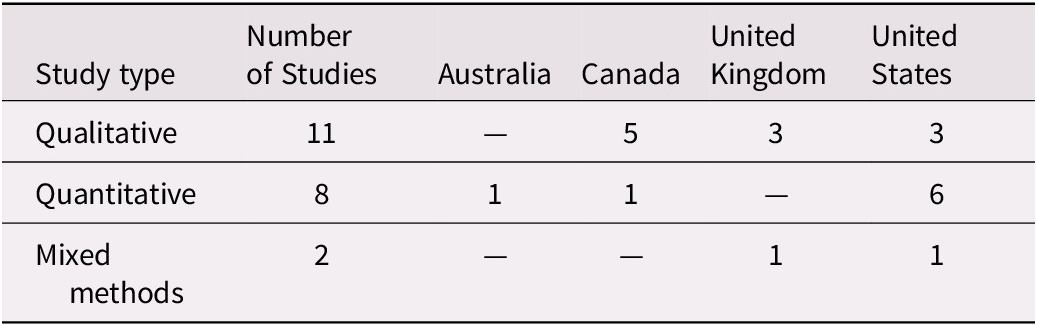

From the 21 articles identified, 11 were qualitative, 8 quantitative, and 2 were mixed methods (Table 2). Nineteen of the studies included an evaluation component to assess the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing stigma of dementia, while the other two articles focused on informing the development of an intervention. The majority of the articles were exploratory in nature and were small-scale pilot studies. The articles were from 4 countries: 10 from the United States, 6 from Canada, 4 from the United Kingdom, and 1 from Australia.

Table 2. Study design and location

Interventions

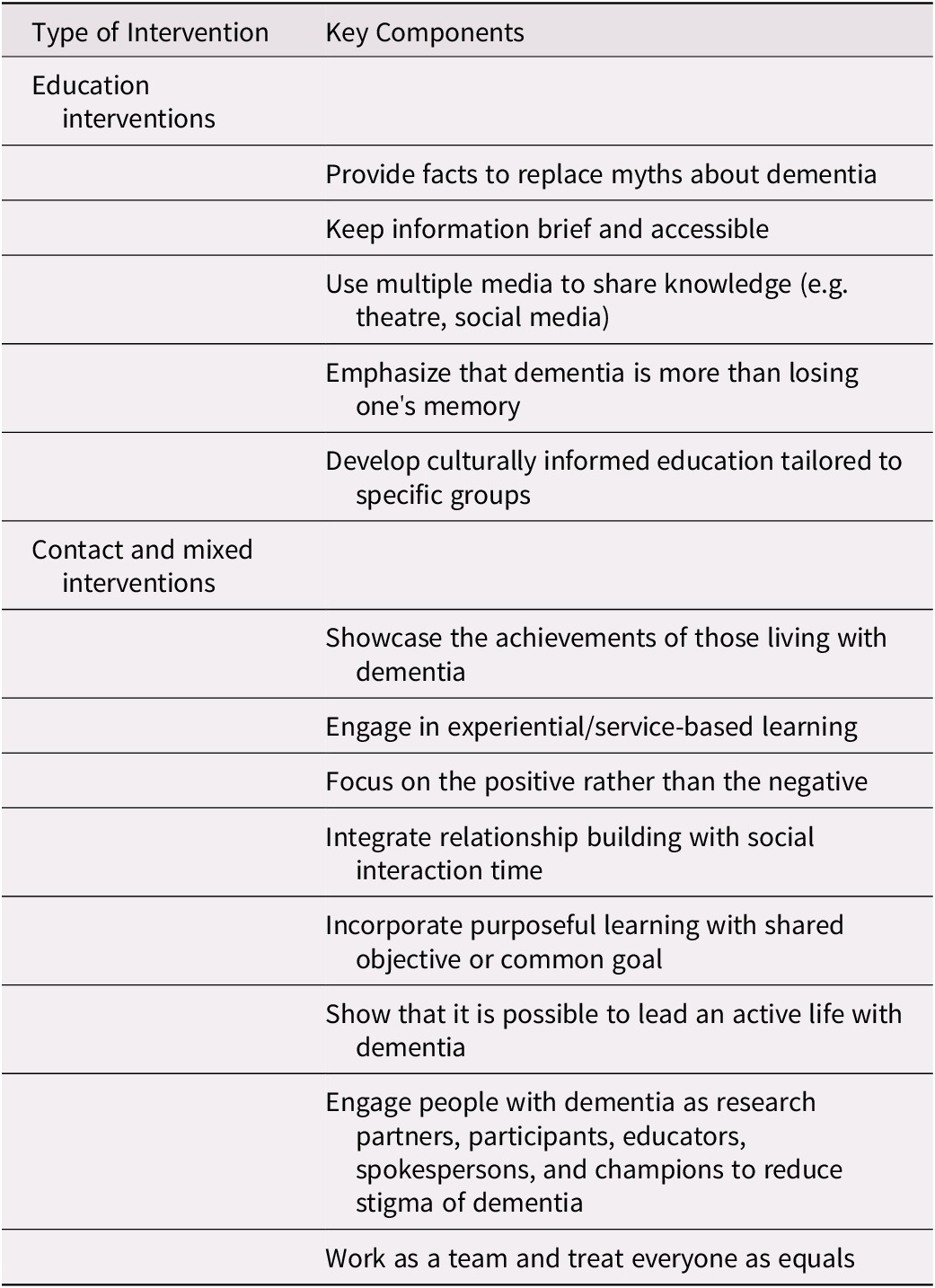

Eleven articles focused on reporting education interventions to improve dementia knowledge and reduce stigma. Eight of the articles used contact interventions, and two studies used mixed (e.g., education and contact) interventions. No studies were identified that addressed protest interventions. An overview of the key components for education, contact, and mixed interventions is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Summary of key components of stigma reduction interventions reviewed

Education interventions

Presentations

Two of the studies included interventions focused on education through presentations targeting students and/or the general public (Baillie, Beecraft, & Woods, Reference Baillie, Beecraft and Woods2015; Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Gibson, Torres, Irizarry, Rodriguez and Tang2016). Baillie et al. (Reference Baillie, Beecraft and Woods2015) Dementia Friends intervention consisted of a 1-hour presentation to 450 nursing students to learn five brief facts and dispel myths about dementia. The session was evaluated through students’ voluntarily writing lessons learned and intended actions (e.g., to educate others) on sticky notes. The presentation was considered effective based on the 418 completed sticky notes, with 456 comments on knowledge learned and 369 on intended actions. A key component of this study was keeping the educational materials brief and accessible by focusing on five simple facts.

Un Cafe´ por Alzheimer (Friedman et al., Reference Friedman, Gibson, Torres, Irizarry, Rodriguez and Tang2016) was a multi-component intervention using different media such as in-person educational sessions and a Facebook page to advance knowledge about AD. The educational sessions included basic information on AD risk factors, definition, diagnosis, and medications. After the session, people were invited to share stories, ask questions, and follow the Facebook page. The sessions were attended by 212 participants, and 51 participants completed the pre- and post-survey evaluations. Based on the 51 voluntary evaluations and the Facebook postings, the researchers found improved general knowledge of AD and its related risk factors. Key components associated with this study included that usage of different mediums (e.g., presentations and Facebook) to mobilize dementia knowledge and education.

Theatre and film

Six of the articles consisted of interventions using theatre-style plays about dementia (Burns et al., Reference Burns, Watts, Perales, Montgomery, Morris and Mahnken2018; Jonas-Simpson et al., Reference Jonas-Simpson, Mitchell, Carson, Whyte, Dupuis and Gillies2012; Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Grigorovich, Dupuis, Jonas-Simpson, Mitchell and Gray2018; Mitchell, Dupuis, & Jonas-Simpson, Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Jonas-Simpson2011; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Dupuis and Jonas-Simpson2011) and a film (Zheng, Chung, & Woo, Reference Zheng, Chung and Woo2016). These articles focused on research-informed plays about people living with dementia. Using pre and post-tests, the articles all reported improved knowledge and attitudes towards persons with dementia. Key components of these studies emphasized the usage of theatrical plays to share dementia education, knowledge, and awareness.

One study used a film in Cantonese as an educational intervention to show common life struggles of dementia and care giving (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Chung and Woo2016). One hundred and fifty Chinese Americans completed a dementia stigma questionnaire prior to the film, and of these only 90 were asked to provide feedback after the film. The study reported that 89 per cent (n = 80) of respondents found the film useful for improving knowledge and addressing misconceptions of dementia (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Chung and Woo2016). Key components of this research included cultural sensitivity and tailoring dementia education towards specific groups.

Curriculum-based interventions

Three studies focused on the development of educational curricula to reduce stigma and improve knowledge of dementia-related stigma (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Udelson, Kanetsky, Liu, Cassidy and Welter2018a; O’Conner, Mann, & Wiersma, Reference O’Conner, Mann and Wiersma2018; Parveen, Farina, Shafiq, Hughes, & Griffiths, Reference Parveen, Farina, Shafiq, Hughes and Griffiths2018). Herrmann et al. (Reference Herrmann, Udelson, Kanetsky, Liu, Cassidy and Welter2018a) developed and tested a stigma awareness and education curriculum for the 21 member staff of an Alzheimer’s Association Chapter. The curriculum covered a range of topics, from the effects of stigma to challenging real-life scenarios of stigma. Using pre and post- surveys, the researchers found that staff had an improved ability to identify and address issues of stigma. A key component of this study focused on the need for dementia education to be brief and accessible for participants (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Udelson, Kanetsky, Liu, Cassidy and Welter2018a).

Two studies did not include interventions but aimed to inform educational interventions to support dementia education and challenge stigma. A study by Parveen et al. (Reference Parveen, Farina, Shafiq, Hughes and Griffiths2018) conducted focus groups with 42 students (ages 12–18) to establish the dementia education needs of adolescents. The findings highlighted the need for more dementia awareness and preferred methods of education (e.g., videos and social media) for adolescents. A key component from this study was the importance of targeted interventions tailored towards specific age groups.

Another study used a peer support model to develop an intervention of a proposed educational curriculum to help people with dementia live well and challenge dementia stigma (O’Conner et al., Reference O’Conner, Mann and Wiersma2018). The participants included eight people with dementia (ages 57–82) who met regularly for 16 monthly group meetings. A key component of this study included recognizing the expertise of people with dementia to educate and challenge dementia-related stigma.

Contact interventions

A variety of contact interventions were identified including: intergenerational storytelling; performing arts such as an intergenerational choir, ballet, and orchestra; and visual arts programs.

Intergenerational storytelling

In a mixed-methods study, Di Bona, Kennedy, & Mountain (Reference Di Bona, Kennedy and Mountain2017) used the Adopt a Care Home program to educate children (ages 9–10) about dementia by visiting people with dementia. A Lifestory booklet was used to encourage conversation and reinforce the children’s literacy skills. Using pre and post-intervention dementia awareness questionnaires, observations, interviews, and focus groups, the study found that the program increased children’s knowledge of dementia (Di Bona et al., Reference Di Bona, Kennedy and Mountain2017). Key components of this study highlighted the importance of intergenerational contact and social interaction for improving dementia knowledge among young children.

Another study (George, Stuckey, Dillon & Whitehead, Reference George, Stuckey, Dillon and Whitehead2011) used TimeSlips, a group-based storytelling program held over the course of a month, with persons with dementia and 15 medical students. At the end of the term, course evaluations found more positive attitudes towards people with dementia. Key components of this study included relationship building and social interaction between medical students and people with dementia outside of the medical setting.

Performing arts

Four articles examined performing arts interventions including a choir, ballet, and orchestra performance. Two of the articles focused on an intergenerational choir as a contact intervention between college students and people with AD (Harris & Caporella, Reference Harris and Caporella2014, Reference Harris and Caporella2018). This research involved interviews on attitudes and knowledge of AD, collected at different points throughout the study. Over time, students exhibited less stigma and more positive attitudes towards people with AD. Similarly, another intervention used a weekly ballet class with seven children and care home residents with dementia (Canning, Gaetz, & Blakeborough, Reference Canning, Gaetz and Blakeborough2018). Using semi-structured interviews over 6-month intervals, the study found that over time, the children described the residents more positively, highlighting their abilities and strengths. Key components from these studies included designated social interaction time, relationship building, and purposeful learning with a shared goal (e.g., choir and ballet).

Another study focused on the general public’s viewing of the BUDI Orchestra, a group of people with dementia, family members, students, and professional symphony members (Reynolds, Innes, Poyner, & Hambidge, Reference Reynolds, Innes, Poyner and Hambidge2017). Qualitative, open-ended, voluntary, self-completion questionnaires from the audience (n = 109) at three public performances were used for evaluation. Before viewing the performances, 53 per cent of respondents had low or no expectations of the orchestra formed of people with dementia. Following the performances, all respondents (108) except one reported that the orchestra either met or exceeded their expectations. A key component of this study was challenging stereotypes by showcasing the achievements of people with dementia in the orchestra.

Visual arts

Two articles focused on a visual arts intervention with college students and people with dementia (Lokon, Li, & Kunkel, Reference Lokon, Li and Kunkel2018; Lokon, Li, & Parajuli, Reference Lokon, Li and Parajuli2017). The Opening Mind through Arts was a service-learning program offered for a semester in which students were paired with elders with dementia to support the elders’ creation of visual art projects. Using pre- and post-surveys, the study found improvements in the students’ attitudes and comfort levels towards people with dementia. Key components of this study included focusing on the positive, allocated social interaction time, and a shared goal of artwork.

Mixed interventions

Two studies combined education and contact interventions (Kimzey, Mastel-Smith, & Alfred, Reference Kimzey, Mastel-Smith and Alfred2016; Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Hall, Cridland, Fleming, Brennan-Horley and Guggisberg2018). The Dementia Friendly Kiama (Phillipson et al., Reference Phillipson, Hall, Cridland, Fleming, Brennan-Horley and Guggisberg2018) pilot consisted of two events involving people with dementia as educators and spokespersons in panel discussions. Two surveys were conducted with adults using validated scales to assess the study’s impact. The study found that intervention attendees had fewer negative views about dementia diagnosis, compared with people who did not attend an event. Key components of this study included collaboration with people with dementia as educators, spokespersons, and champions to reduce stigma of dementia.

Kimzey et al.’s (Reference Kimzey, Mastel-Smith and Alfred2016) study examined the impact of education interventions (e.g., on-line modules), contact interventions (e.g., clinical rotations with people with AD) and no interventions on 94 nursing students’ knowledge and attitudes of people with AD. Using mixed methods, the study found that clinical placements increased knowledge and improved attitudes compared with an online module and no AD-specific intervention. Key components of this study included the importance of hands-on experiential learning and designated social interaction time between students and people with AD.

Discussion

The stigma of dementia is a well-documented issue that reduces the quality of life for people living with dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019). Despite this knowledge, there are no known attempts to examine the current state of the literature on interventions to address dementia-related stigma. However, reducing dementia-related stigma is necessary to support the uptake of early dementia diagnosis, facilitate cognitive health promotion, and optimize health care services to support people with dementia. Moreover, an early diagnosis enables people with dementia to acquire relevant information and support services, plan for the future, and access pharmaceutical treatments that may improve their quality of life (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Accordingly, the aim of this scoping review was to synthesize the existing literature and identify key components of interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia.

We found that Corrigan and Penn’s (Reference Corrigan and Penn1999) stigma reduction framework provided a useful approach for classifying the various interventions and their key components. For example, this review found that key components of education interventions included: providing facts to replace myths, using multiple mediums to improve dementia knowledge, and developing culturally informed strategies for specific audiences. Key components of contact and mixed interventions included: showcasing the achievements of people with dementia, highlighting the different stages of dementia, relationship building, and engaging in purposeful learning. No studies examined protest interventions (i.e., drawing public attention to stigma behaviours). In the broader mental health and stigma literature, few studies evaluate protest interventions, possibly because of concerns about creating a rebound of stigma or entrenching stigma-related attitudes (Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz, & Rusch, Reference Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz and Rusch2012). However, protest interventions may repress overt stigma-related behaviours, suggesting that there is some value to this approach (Corrigan et al., Reference Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz and Rusch2012). This review, which focused on education and contact interventions, makes an important contribution to the literature, as it provides a comprehensive understanding of existing interventions to reduce dementia-related stigma to inform future health care policies, programs, and services for people with dementia.

Few studies addressed the importance of culture or geographic context (e.g., urban, rural or remote) in developing interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia (Kontos et al., Reference Kontos, Grigorovich, Dupuis, Jonas-Simpson, Mitchell and Gray2018; Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Chung and Woo2016). However, local culture and context play an important role in addressing stigmatizing beliefs surrounding dementia. For example, in rural South Africa, dementia is often viewed as witchcraft rather than as a disease (Mkhonto & Hanssen, Reference Mkhonto and Hanssen2018). Consequently, cultural beliefs and geographical context may affect whether dementia is identified, whether there is early diagnosis, and whether it is openly accepted within the community (Australian Government, 2009). Accordingly, more research is needed to develop culturally and geographically informed interventions to address the stigma of dementia.

Consistent with existing literature (Herrmann et al., Reference Herrmann, Welter, Leverenz, Lerner, Udelson and Kanetsky2018b), our scoping review found that studies often did not provide clear conceptualizations or operationalizations of dementia-related stigma. However, it is important for a study to clearly define stigma and to identify the specific measures and outcomes used to assess the impact of the intervention on dementia-related stigma. This would enhance the replicability of the study and enable researchers to evaluate and compare study findings.

This scoping review also identified the need for more rigorous methods in future research on dementia-related stigma. More specifically, many of the studies suffered from methodological limitations including: poorly defined samples (e.g., lack of consistency in reporting demographic information of the participants such as age and/or gender), informal evaluation methods, and self-report evaluation methods that are subject to positive impression management. These limitations make it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the effectiveness of the specific intervention or intervention type on reducing dementia-related stigma. Accordingly, these are important considerations for future research.

Limitations

This review aimed to summarize the existing literature and identify key components of interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia. Subsequently, the findings from this review are relevant for health professionals, community leaders, and policy makers working to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia. However, our review is not without limitations including the exclusion of non-English manuscripts, and of manuscripts published before January 2008. Consequently, it is possible that relevant research was excluded from this review.

Another limitation of this work is the lack of a quality assessment to evaluate the methods used in each of the 21 studies. The aim of this review was to synthesize the scope of the existing literature, and it refrained from assessing the quality of the studies. Accordingly, future research would benefit from an instrument to formally assess the quality of the work, including the specific measures used to evaluate the interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia. Additionally, further research is needed to evaluate the long-term impact of the different interventions in reducing stigma over time.

Conclusion

Dementia-related stigma can detrimentally impact interactions with health care providers, experiences in acute care settings, and access to specialist services (e.g., geriatricians and neurologists), and can lead to misdiagnosis, social isolation, depression, and suicide (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Dementia-related stigma pervades society and even health care institutions such as primary care, hospitals, and long-term care settings (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2019; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019). Research on interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia is critical for improving the quality of life of people living with dementia and their care partners. This scoping review synthesized the existing literature and key components of interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia. Our review makes an important contribution to the literature as it identifies a variety of interventions to address dementia-related stigma ranging from a culturally tailored educational film (Zheng et al., Reference Zheng, Chung and Woo2016) to an intergenerational choir consisting of college students and people living with dementia (Harris & Caporella, Reference Harris and Caporella2018). In moving forward, more rigorous methods are necessary to develop stronger evidence-informed interventions to reduce the stigma of dementia. In addition, future studies need to clearly define stigma and articulate the specific measures used to assess dementia-related stigma in order to enhance the replicability and utility of the study findings. The findings from our study are relevant to health care providers, researchers, and policy makers working to inform the development of stigma reduction interventions to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia.