Introduction

The Research & Development (R&D) strategy for health in the UK (Department of Health, 2006) has established an infrastructure of research networks, developed under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UK CRC) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), which, it is anticipated, will produce an efficient and effective interface between the NHS and academia to enable high-quality clinical research. Such networks, among other things, aim to produce research for practice by supporting recruitment to clinical trials. This paper suggests some problems in relation to assumptions in this strategy, which imply that once networks have been established, the interface with practice is somehow ‘sorted’. It explores particular issues for the primary care practice–research interface, where recruitment and capacity building have experienced significant barriers and difficulties in the past. The paper pays particular attention to valuing ‘close to practice’ principles in relation to the effectiveness of networks, and their ability to build capacity, and highlights the importance of process issues in achieving network aims. The paper highlights the experience and learning of existing networks in primary care, and evidence about what supports recruitment to clinical trials. The current lack of emphasis on developing research skills and leadership in frontline practitioners is also considered, and specific concerns regarding reciprocity between research and practice partnerships are highlighted. The need for development of such skills in non-clinical researchers is also important but not the subject of this paper. Concern is expressed that if these issues, and others related to the social capital of networks, are not addressed, then the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) will not be able to deliver on its objectives.

Background

There has been considerable investment in developing research networks in primary care internationally (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Wild, Harvey and Fenton2000; Van Weel et al., Reference Van Weel, Smith and Beasley2000; Farmer and Weston, Reference Farmer and Weston2002; North American Primary Care Research Group Committee on Building Research Capacity and the Academic Family Medicine Organisations Research Sub-Committee, 2002; Lindbloom et al., Reference Lindbloom, Wewigman and Hicker2004). The emphasis and purpose of Primary Care Research Networks (PCRNs) vary from maximising participation in research to developing a culture of producing research within practice. Many authors argue that networks have a function to move practitioners from participation to becoming active researchers in their own right (Clement et al., Reference Clement, Pickering, Rowlands, Krishnan, Candy and De Lusignan2000; Ryan and Wyke, Reference Ryan and Wyke2001; Farmer and Weston, Reference Farmer and Weston2002).

In the last decade, the number of PCRNs in the UK expanded based on recommendations from the Mant report (NHS Executive, 1997), which stressed the need to develop research for, with and by primary care practitioners. The National Coordinating Centre for Research Capacity Development funded 20 PCRNs within their programme of work to increase research capacity defined as ‘a process of individual and institutional development which leads to higher levels of skills and greater ability to perform useful research’ (Trostle, Reference Trostle1992, p. 1321).

The importance of networks in the prosecution of research per se should not be underestimated. Research for practice can be undertaken through using evidence gathered from practice (for example, using electronic data to undertake epidemiological research), and can assist research with practitioners by promoting active collaborations. Engaging practitioners to help with recruitment for large projects could fit into this category, and networks have been found to be important in accessing representative populations in primary care in this regard (Hammersley et al., Reference Hammersley, Hippersley-Cox, Wilson and Pringle2002). In addition, by adopting a learning and participatory approach, networks can enable research by individual practitioners and practice teams to grow ‘bottom-up’ research ideas.

Over the past year there has been initiation of disease-specific networks, comprehensive networks and a national structure of PCRNs. In these developments, however, the concept of developing capacity seems to have lost momentum and emphasis, and has been replaced by notions of recruitment and ‘participation’. In a recent discussion document (Department of Health, 2006), networks are recognised as essential to the proposed strategy; however, capacity development for practitioners is no longer a core network function. The purpose of networks is described as follows: increasing participation through maximising recruitment, integrating research and patient care; increasing the quality, speed and coordination of clinical research; and providing an explicit means by which the NHS can meet the health research needs of the industry. While these aims are understandable they may well miss out on essential elements of linking and developing research that is close to practice, in nurturing the important synergies between practice and research, and in developing the research capacity of individuals and teams within the networks.

Recent literature points to a history of difficulties and poor working practices between researchers and primary care. For example, McKinley et al. (Reference McKinley, Dixon-Woods and Thornton2002, p. 971) state:

practitioners can feel they are regarded as mere conduits to reservoirs of people on their lists by researchers who have paid scant regard to practitioners preferences about study designs and recruitment strategies.

Many of the networks that have been developed in primary care up to this point have been sensitive to this view, and have been shaped around trust and social capital (Fenton et al., Reference Fenton, Harvey, Griffiths, Wild and Sturt2001), using methods that include ‘bottom-up’ and whole systems approaches to involve practitioners as leaders and ‘doers’ of research, as well as collaborators and patient recruiters (Thomas and While, Reference Thomas and While2001; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Griffiths, Kai and O’Dwyer2001). Other authors have focussed on the importance of process in the evaluation of these networks and suggest that such process issues are essential in building a body of understanding about what works in producing useful research (Griffiths et al., Reference Griffiths, Wild, Harvey and Fenton2000; Fenton et al., Reference Fenton, Harvey, Griffiths, Wild and Sturt2001). Capacity building can not only support incentives for practitioners to participate in networks but also help to support and build connections to show how research can be beneficial to practice and to patients (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Griffiths, Kai and O’Dwyer2001).

Applying principles of capacity building to shape the conduct of research networks

The principles of research capacity building are useful in mapping some of the process issues which could inform a code of conduct for networks, and which may also contribute to their productivity. These principles can inform appropriate approaches to undertaking research with practitioners, avoiding the difficulties highlighted by McKinley and colleagues, and can ensure elements of ownership, reciprocity and incentives.

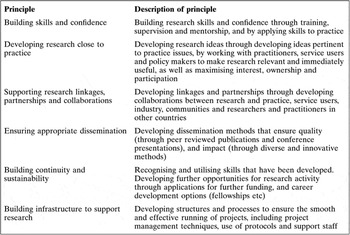

Trent Research and Development Support Unit (RDSU) has developed some principles of research capacity building through experience of supporting research alongside practice, and the use of research evidence (Cooke, Reference Cooke2005). These are listed in Box 1. A number of these issues are fundamental to the new networks, but some may be at risk as discussed above. In particular, it is the close to practice principle that appears marginalised, but which is important, not only for the effective running of research projects but also when the impact of research on primary care practice is considered.

Box 1 Principles of Research Capacity Building

Note: these principles have been developed through the work of Trent RSDU based on the framework by Cooke (Reference Cooke2005).

Closeness to practice: an important principle for productivity, recruitment and impact

Research, which is conducted ‘close’ to practice, is useful for two reasons. Firstly, in working closely with practitioners during the development and conduct of research projects, they are more likely to reach a satisfactory conclusion, and be clinically appropriate (Parry et al., Reference Foy, Parry, Duggan, Delaney, Wilson, Lewin-van den Broek, Lassen, Vickers and Myres2003). A systematic review addressing barriers to participation in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Prescott et al., Reference Prescott, Counsell, Gillespie, Grant, Russell, Kiauka, Colthart, Ross, Shepherd and Russell1999) has highlighted some key issues for working close to practice. The review highlights that barriers to practitioner participation include:

• fears around the impact on the doctor–patient relationship;

• concern for patients as they may not receive the treatment that turned out to be the best;

• the perception and importance of, and interest in, the research topic;

• incompatibility of the research protocol with normal practice;

• time constraints;

• training.

Most of the studies included in the review were based in secondary care, but many of the barriers are valid, and are often compounded, in primary care contexts. For example, the relationship with patients in primary care is not only for a single treatment period but generally for a long period of time. Challenges to the quality and rapport in the practitioner–patient relationship, perhaps as a result of research activity, will therefore have a longer-term impact. Prescott et al. (Reference Prescott, Counsell, Gillespie, Grant, Russell, Kiauka, Colthart, Ross, Shepherd and Russell1999) and others reviewing RCTs in primary care (Foy et al., Reference Foy, Parry, Duggan, Delaney, Wilson, Lewin-van den Broek, Lassen, Vickers and Myres2003) have come to similar conclusions about methods of improving the effectiveness of recruitment strategies to inform the conduct of networks. These include working closely with practitioners who have a role in developing priorities, shaping research ideas and informing methodologies that are more pragmatic in nature. Empirical evidence suggests that practitioners are more likely to engage in research if they see its relevance to their own practice, and developing research protocols with practitioners can ensure that research work blends better with practice work, and will pay attention to time constraints. Training and dialogue with practitioners in networks can develop research skills, and will help to ‘unpack’ ethical issues and research–practice dilemmas (Foy et al., Reference Foy, Parry, Duggan, Delaney, Wilson, Lewin-van den Broek, Lassen, Vickers and Myres2003). PCRNs established following the publication of the Mant Report (NHS Executive, 1997) developed close relationships with local RDSUs. Developing strong links between the networks and RDSUs is important here, as they may well have a role to play in assisting in these process issues: in supporting training within networks, priority setting and protocol development at the practice–research interface.

Secondly, developing research close to practice can mean results are more likely to be taken up in practice and have some impact (National Audit Office, 2003). Networks may help overcome the translational block of integrating new knowledge into practice (Lindbloom et al., Reference Lindbloom, Wewigman and Hicker2004).

Close to practice: keeping a focus on research capacity building in practitioners

Some of the key literature around generating knowledge for primary care practice highlights the need for developing research practitioners (Farmer and Weston, Reference Farmer and Weston2002; North American Primary Care Research Group Committee on Building Research Capacity and the Academic Family Medicine Organisations Research Sub-Committee, 2002). Examples are given of how networks can help build capacity in primary care practitioners, by developing skills and knowledge in research, and by nurturing interest and providing opportunities and research experience (Thomas and While, Reference Thomas and While2001; Macfarlane et al., Reference Macfarlane, Shaw, Greenhalgh and Carter2005). Practitioner-led research activity has been promoted through a variety of mechanisms in PCRNs, including a whole systems approach where research is shaped, and led by network members (Thomas and While, Reference Thomas and While2001), by funding pilot work through bursary schemes supporting external grant submissions by network members (Pitkethly and Sullivan, Reference Pitkethly and Sullivan2003), and through other approaches such as designated research teams. The notion that networks may provide opportunities as a ‘way into’ research is an important concern in building a primary care academic workforce. The lack of focus on this issue in the new networks is of concern. Not all primary care practitioners want to be research leaders, and many are happy to contribute to the research endeavour by engaging in research at a minimum level of participation; however, others may welcome research opportunities that can act as an incentive. Financial incentives have been well documented as an important consideration in recruitment (Foy et al., Reference Foy, Parry and McAvoy1998), but in our experience this it is not the full story. Issues of professional development, professional interest, benefits to patients, the quality of services and professional status also need to be considered.

Conclusions

This paper has highlighted some of the key process issues that are important in the development and future conduct of the networks under the direction of the UKCRN. The importance of process issues in how the networks should operate has been stressed, and we suggest that adopting research capacity building principles, in particular that of working closely with practice, should shape a code of network conduct and perhaps form the basis of accreditation, which will facilitate their productivity. Strong links with RDSUs are also stressed to maximise expertise that currently exists in this regard. Concern is expressed about the lack of continuing opportunity to build research capacity in the health care workforce in the new UKCRN networks. The current emphasis on recruitment and participation may well have the unintended consequences of reducing the infrastructure and potential of academic primary care, and research productivity in the future.

Declaration

The authors have no competing interests.