For decades, the United States criminal justice system relied heavily on incarceration as a crime-control strategy, despite the extraordinarily high costs, limited crime-prevention value, and disproportionate impact on the black community (Reference AlexanderAlexander 2012; Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference Durose, Cooper and SnyderDurose et al. 2014; Reference Maruna, Toch, Travis and VisherMaruna and Toch 2005; Reference PetersiliaPetersilia 2003; Reference TonryTonry 2011; Reference WacquantWacquant 2002; Reference WesternWestern 2006). According to the research, we have reached a point of diminishing returns on the use of incarceration, such that increases in imprisonment in recent years generated less crime reduction than in the past, with some researchers indicating either no effect or a criminogenic effect of imprisonment (Reference Johnson and RaphaelJohnson and Raphael 2012; Reference Lofstrom and RaphaelLofstrom and Raphael 2016; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014; Reference TonryTonry 2011). At the same time, the country appears to be entering a transitional criminal justice era, characterized by prison downsizing and a bipartisan shift toward alternative approaches to crime control (Reference Clear and FrostClear and Frost 2014; Reference Dagan and TelesDagan and Teles 2014; Reference Petersilia and CullenPetersilia and Cullen 2015). According to Reference RaphaelRaphael (2014), “most activists, criminal justice professionals, and informed observers of U.S. corrections policy sense a profound political change and the opening of a policy window where fundamental reform is a real possibility” (580). However, reducing the prison population is not a simple feat; without the implementation of other criminal justice reforms designed to prevent crime and reduce recidivism, lower levels of imprisonment may result in increased crime (Reference BushwayBushway 2016; Reference Petersilia and CullenPetersilia and Cullen 2015).

To minimize the possible criminogenic effects of prison downsizing, many experts advocate for the reallocation of resources from imprisonment to other possible interventions, ranging from early childhood interventions to a renewed interest in policing strategies (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014). Scholars have focused recent attention on the latter, arguing that simply increasing the resources available to the police is not enough; rather, fundamental changes in the nature of policing are also necessary. One common recommendation is for police to shift away from the traditional style of policing, which focuses on enforcement, to a sentinel style of policing that focuses on preventative patrolFootnote 1 (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). A second recommendation is for police to adjust deployment strategies to focus on high crime areas, or “hot spots,” and known offenders (Reference Braga, Papachristos and HureauBraga et al. 2012; Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015). Many hot spots interventions exist with varying support, including aggressive order-maintenance policing, offender-focused policing, increased patrols, and situational prevention. The deterrence doctrine is the premise behind these calls for shifts in the style and focus of policing, advocating for crime prevention through interventions that increase the perceived risk of apprehension and limit criminal opportunities, as opposed to focusing on the severity of punishment (Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015).

As recognized by its advocates, this type of reform represents a “major organizational challenge” to police agencies (Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015: 93) and “will require significant changes in American policing” (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015: 27). However, scholars have overlooked one of the most basic but critical questions in this debate—namely, whether the general public would be receptive to such fundamental changes in policing. There is growing evidence that the public supports prison downsizing (Reference SundtSundt et al. 2015; Reference ThieloThielo et al. 2016). Yet, we know little about whether Americans believe there is value in diverting criminal justice funds from imprisonment to policing, or support the recommended deterrence-based changes in either the style or focus of policing. Perhaps most surprisingly, we currently lack information about whether the public supports hot spots policing as a general policy approach.

This research void is significant given the current crisis of confidence in the police (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2015), especially following the police shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri and subsequent publicized deadly police-citizen encounters, as well as the Black Lives Matter movement. Changes in policing strategies, especially if evaluated negatively by the public, can influence Americans’ trust and confidence in the police, which, in turn, can affect citizens’ cooperation and compliance with law enforcement (Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 1990; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo 2002; Reference Tyler and JacksonTyler and Jackson 2014; Reference Tyler, Schulhofer and HuqTyler et al. 2010). Reference Kochel and WeisburdKochel and Weisburd (2017) report evidence that implementing hot spots policing reduces, at least temporarily, perceptions of police fairness and trustworthiness. Such potential backfire effects are especially salient for minorities, whose communities are likely to be targeted by the suggested policy changes and who already view the police as less legitimate (Reference Bobo, Thompson, Markus and MoyaBobo and Thompson 2010; Reference PeckPeck 2015; Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 2004; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer and Tuch 2002, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2004, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2006). These communities are likely to be unsupportive of policies like hot spots policing, which are more likely to stop crimes but also create distrust of the police. Implementation of policies negatively viewed by minorities can further weaken police-community relations by increasing perceptions of legal cynicism, feelings of legal estrangement and stigmatization, and fears of discrimination (Reference BellBell 2016; Reference Kirk and PapachristosKirk and Papachristos 2011; Reference WacquantWacquant 2007), or by fostering concerns of unequal policing.

Additionally, recent research shows that popular attitudes toward particular policies can set boundaries for policy implementation (Reference PiqueroPiquero et al. 2010; Reference ThieloThielo et al. 2016). More broadly, there is strong evidence that policy makers and practitioners are highly sensitive to public opinion on criminal justice (Reference Brace and BoyeaBrace and Boyea 2008; Reference Canes-Wrone and ShottsCanes-Wrone and Shotts 2004; Reference EnnsEnns 2016). The implication is that it may be difficult to implement and sustain policing reforms, even if they are effective, in the absence of public support. This possibility is noteworthy in the current political climate, where policy makers have seemingly ignored public opinion on certain issues, and we have yet to see the repercussions. Some scholars would argue that policy-making institutions cannot remain for long out of line with the opinions of the majority without risking eventual loss to their legitimacy and support (Reference DahlDahl 1957; Reference EastonEaston 1965, Reference Easton1975; Reference Scherer and CurryScherer and Curry 2010). In this view, the new administration's adoption of policies disfavored by the public can broaden the existing legitimacy crisis.

For these reasons, our study explores the attitudes of the general public toward the contemporary developments in crime control policy. Specifically, drawing on survey data from a nationally representative sample of Americans, we evaluate the public's assessments of the cost-effectiveness of policing versus prison, support for sentinel and hot spots policing, and preferences for different police intervention strategies for hot spots. We then assess whether these attitudes vary across demographic groups, particularly blacks, Hispanics, and lower income individuals who are often the groups most affected by many of these police interventions. We begin with a discussion of the relevance of public opinion to the contemporary policing developments and then proceed with an overview of these developments to give context to the survey questions asked.

Relevance of Public Opinion

Crime scholars have brought several policing reforms to the forefront, suggesting a reinvestment and reorientation in policing. At the same time, there is a current crisis in policing among the public evidenced by the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and sustained with increased negative publicity surrounding deadly police-citizen interactions (Reference BellBell 2016; Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2015). According to Reference WeitzerWeitzer (2015), these incidents “have rattled public confidence in the police and sparked fresh debate on reforms” (475). Reference JonesJones (2015) reports that confidence in policing fell to a 22-year low. Likewise, data from the General Social Survey reveal that the number of Americans who believe that “too little” is being spent on “law enforcement” fell to an all-time low of 47 percent in 2014, the most recent year available (authors’ analysis). So while scholars are debating the merits of shifting more resources to police, the media and public are debating needed reforms to police-community relations (Reference WeitzerWeitzer 2015).

Within this context and given the minimal public opinion studies in the area, it is unclear how the public will respond to the proposed changes in policing. Yet, their response is significant for two primary reasons. First, policing strategies disfavored by the public can have consequences for police legitimacy. Within the process-based model of policing, it is argued that procedural justice is a key factor in influencing perceptions of legitimacy, such that the public has more trust and confidence in authorities who treat citizens with respect and make objective decisions (Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 1990, Reference Tyler2004; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo 2002). Negative evaluations of procedural justice and legitimacy can have consequences for both cooperation with law enforcement and compliance with the law (Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 1990; Reference Tyler and HuoTyler and Huo 2002). The recent media attention surrounding police encounters calls police procedural justice and legitimacy into question (Reference BellBell 2016). In particular, Reference RosenfeldRosenfeld (2016) discusses a “Ferguson effect,” not in the sense of police disengagement as a result of increased media attention, which is one interpretation, but regarding an “empowerment” of criminals who no longer view the police as a fair and legitimate authority. The implementation of policing policies not supported by the public can contribute to a growing resentment toward police. Administrators and bureaucrats within police departments acknowledge that legal claims and protests erode legitimacy and produce calls for “legalized accountability” (Reference EppEpp 2009). Concern over legitimacy is particularly relevant for those policy proposals, like some variants of hot spots policing, that involve “intensive law enforcement and a readiness to arrest for low-level offenses,” which Reference Schulhofer, Tyler and HuqSchulhofer et al. (2011) predict are “likely to arouse resentment, weaken police legitimacy, and undermine voluntary compliance with the law” (351; Reference Rosenbaum, Weisburd and BragaRosenbaum 2006).

An additional concern regarding hot spots policing is that members of the public may perceive the targeting of certain areas by police as unfair or discriminatory, and these sentiments may diverge along race and class lines. The early work of Reference BlalockBlalock (1967) placed emphasis on minority group threat, such that majority groups are apt to mobilize resources against a growing minority that threatens the social dominance of the majority group. Perceptions of threat influence support for social control mechanisms when it comes to crime, with evidence suggesting that whites who typify crime as a minority phenomenon are more supportive of punitive punishments (Reference Chiricos, Welch and GertzChiricos et al. 2004; Reference WelchWelch et al. 2011). Among conservatives, this relationship is particularly salient (Reference Chiricos, Welch and GertzChiricos et al. 2004), with additional evidence suggesting a connection between conservative ideology and racial threat (Reference Craig and RichesonCraig and Richeson 2014a,Reference Craig and Richeson2014b). Given that many hot spots targets are predominantly disadvantaged, minority communities, white respondents of a higher social status and more conservative leaning may be more supportive of hot spots interventions, while low-income, minority respondents would be much less receptive to such changes. The latter would have consequences for police legitimacy. Evidence already suggests hot spots policing affects low-income, minority communities and can be damaging to their communities (Reference KochelKochel 2011; Reference Rosenbaum, Weisburd and BragaRosenbaum 2006).

The concerns of the black community would be noteworthy in this regard. It is widely acknowledged that the era of mass incarceration has marginalized the black community, with young, black males targeted as dangerous superpredators (Reference AlexanderAlexander 2012; Reference Bobo, Thompson, Markus and MoyaBobo and Thompson 2010; Reference TonryTonry 2011; Reference Van Cleve and MayesVan Cleve and Mayes 2015; Reference WacquantWacquant 2002; Reference WesternWestern 2006). As a result, scholars argue blacks have become an underclass excluded from many of the benefits of society, including employment, education, welfare, and political participation, and view mass incarceration as a modernized version of slavery and Jim Crow (Reference AlexanderAlexander 2012; Reference Bobo, Thompson, Markus and MoyaBobo and Thompson 2010; Reference Dagan and TelesDagan and Teles 2014; Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2015; Reference WacquantWacquant 2002; Reference WesternWestern 2006). Reference Bobo, Thompson, Markus and MoyaBobo and Thompson (2010) state that “the current punitive law and order regime and condition of racialized mass incarceration has created a real crisis of legitimacy for the legal system in the eyes of most African Americans” (345). Reference TonryTonry (2011) suggests that the existing prison disparity is partially a result of police purposely targeting minority offenders, as well as policies, like drug arrests, that focus on minority areas. As acknowledged by the President's Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015), “law enforcement cannot build community trust if it is seen as an occupying force coming in from outside to rule and control the community” (11).

Aligned with these sentiments, Reference BellBell (2016) goes a step further and suggests that the real concern is not just procedural justice and police legitimacy, but also “legal estrangement.” She proposes that estrangement involves feelings of cynicism toward the law, combined with a perceived lack of social inclusion. Reference Kirk and PapachristosKirk and Papachristos (2011) define legal cynicism as a “cultural orientation in which the law and agents of its enforcement, such as police and courts, are viewed as illegitimate, unresponsive, and ill equipped to ensure public safety” (1191). Reference BellBell (2016) suggests this cynicism and estrangement emerges from procedural injustice, marginalization by police, and unfair policing policies. Reinvesting money toward hot spots policing may contribute further to the marginalization of certain groups of people, depending on the strategies or interventions employed, and therefore, blacks may oppose these strategies since they already feel excluded from the community and question the legitimacy of the criminal justice system.

Four studies explored whether hot spots policing causes residents of targeted areas to become more afraid of crime or more distrustful or dissatisfied with police. The results are mixed. Three studies found no evidence of changes in fear or policing attitudes (Reference HabermanHaberman et al. 2016; Reference RatcliffeRatcliffe et al. 2015; Reference WeisburdWeisburd et al. 2011). One study, however, found significant, albeit temporary, declines in perceived procedural justice and trust, and a nonsignificant reduction in police legitimacy (Reference Kochel and WeisburdKochel and Weisburd 2017). However, it remains possible that if hot spots policing becomes a more widespread and institutionalized policing strategy, there may be larger and more enduring effects on public opinion. Additionally, studies continue to find that blacks and Hispanics have more negative views of the police and often perceive the police as more unjust than whites (Reference Bobo, Thompson, Markus and MoyaBobo and Thompson 2010; Reference Hagan, Shedd and PayneHagan et al. 2005; Reference PeckPeck 2015; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer and Tuch 2002, 2004, Reference Weitzer and Tuch2005). Reference WeitzerWeitzer (2015) also finds that police show less respect toward residents in disadvantaged communities. Redirecting more police resources to these areas can further delegitimize the police and impede police-community relations. This is especially true given that theory predicts groups predominantly living in low-income communities will disfavor a redirection of resources in this manner.

Second, public opinion can influence the decisions of policy makers. For instance, Reference ThieloThielo et al. (2016) point to growing empirical evidence showing a connection between public punitiveness and the implementation of punitive policies. Citizens may view the downsizing of prisons and shifting of resources to policing as being “soft on crime” (Reference Welsh and FarringtonWelsh and Farrington 2012), and therefore, police-makers and practitioners may sidestep these strategies in place of a more punitive approach. Additionally, research demonstrates that public opinion can influence the decisions of elected officials, including State Supreme Court judges and Presidents, and may even be particularly salient when approval ratings are lower (Reference Brace and BoyeaBrace and Boyea 2008; Reference Canes-Wrone and ShottsCanes-Wrone and Shotts 2004). Elected officials would then be responsive to public opinion as a means of gaining public favor, and presumably more so in election years. As Reference GarlandGarland (2001) suggests, politicians view policy initiatives in light of public opinion and political appeal. In the case of policing, a precondition for successfully implementing changes in police policy may be that the public views the reforms favorably, and policy makers assure the public the state is in control and will continue to protect the people (Reference GarlandGarland 2001). This could be true regardless of the effectiveness of the policing approaches for reducing crime.

As previously noted, the chances for policy reform are salient at this point given that bipartisan discussion is underway regarding an end to mass incarceration (Reference Dagan and TelesDagan and Teles 2014). Some scholars argue that moving the discussion away from the racial disparities and discrimination in mass incarceration to budget concerns and the inability to sustain the expense of incarceration makes agreement along party lines easier (Reference Dagan and TelesDagan and Teles 2014; Reference GottschalkGottschalk 2015). However, moving the discussion away from racial issues in the justice system can be problematic. Reference GottschalkGottschalk (2015) warns about the prior punitive turn in criminal justice policies during a period of bipartisan agreement, such that concerns over failing rehabilitation programs, judicial discretion, and increasing crime rates in the 1970s allowed conservatives to push a punitive agenda. This same scenario is a current concern given the new administration's focus on law and order, where they may favor intensive law enforcement strategies in hot spots (Reference BellBell 2016). The reactions in the 1970s can represent an “urgent and impassioned” response made in consideration of public fears and concerns (Reference GarlandGarland 2001), especially the concerns of southern, working-class whites (Reference TonryTonry 2011). In this way, evaluating public perceptions of police reform, and potential demographic cleavages of support, is important at this juncture given that it can (1) inform the direction of upcoming policies and (2) have implications for the current legitimacy crisis in policing, especially if the reforms are disfavored among certain groups.

Contemporary Developments in Policing

The propositions of deterrence theory are the main premise of the suggested shifts to sentinel and hot spots policing, with a focus on increasing the perceived risk of apprehension (or certainty of punishment) and mitigating the opportunities to commit crime (Reference ClarkeClarke 1997; Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). To refocus efforts in these areas, scholars offer many recommendations about how to shift crime control policy. Three of the most notable are: (1) investing more resources in policing, as opposed to lengthy periods of imprisonment, (2) prioritizing sentinel-style, rather than enforcement-style, policing, and (3) concentrating police resources on crime hot spots (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). We summarize each of these recommendations below along with findings from relevant public opinion research.

Investing More Resources in Policing

Under optimization theory, there is legitimate motivation for reinvesting “criminal justice resources toward interventions with higher returns per dollar spent,” such as policing (Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014: 590). If policy makers reallocate resources toward an alternate intervention with crime-reduction benefits, investing less money in prison does not have to lead to an increase in crime (Reference Lofstrom and RaphaelLofstrom and Raphael 2016; Reference Petersilia and CullenPetersilia and Cullen 2015). Recent research explores the benefit-cost ratio, or the “bang for the buck,” associated with additional policing as an intervention, with results showing it is likely higher than the benefit-cost ratio for additional prison expenditures (Reference Lofstrom and RaphaelLofstrom and Raphael 2016; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014). Evidence suggests that the “bang for the buck” of additional police spending is relatively high, reducing crime costs by $1.63 for each additional dollar spent (Reference Chalfin and McCraryChalfin and McCrary 2013; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014). Therefore, crime reduction from additional policing may actually exceed any crime increase caused by reducing the prison population resulting in a net decline in crime (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014).

The best available evidence concerning public opinion of the cost-effectiveness of policing comes from Reference Cohen, Rust and SteenCohen et al. (2006). They analyzed survey data from 2000 and found that Americans were more willing, on average, to allocate their tax dollars to policing than prisons (325). They also found that a slight majority (52.6 percent) of the public believed more money should be spent on policing (323). This finding is in contrast to a 1996 survey reporting 54 percent of the public believed it was more important to “impose stricter sentences on criminals” than to “increase the amount of police on the street” in order to prevent crime (Reference Cullen, Fisher and ApplegateCullen and Fisher 2000: 27). Although not asking specifically about prisons or policing, a recent study using a national survey conducted in 2009 found that more Americans believed additional resources needed to be focused on “punishing offenders” (28 percent) than “arresting offenders” (9 percent) (Reference BakerBaker et al. 2015: 455).

Moving to Sentinel-Style Policing

Traditionally, police have focused most heavily on their role as apprehension agents, responding to past crime events to solve the crimes (Reference BragaBraga et al. 2011; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). Police can also operate as sentinels or “capable guardians,” where their main task is to patrol and deter crime (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). The move toward greater police surveillance and the rise of “big data” analytics within police forces is indicative of this latter strategy (Reference BrayneBrayne 2014, Reference Brayne2017). The two roles—apprehension agent versus sentinel—represent the distinction between enforcement and prevention. According to Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin (2015), evidence indicates that proactive prevention is more effective than reactive arrest in reducing crime, suggesting that the police should focus more on their sentinel role. Not all scholars agree. For example, Reference Pickett and RochePickett and Roche (2016) argue that this strategy would be ineffective given that objective odds of arrest are at best weakly related to perceptions of apprehension risk. Reference BrayneBrayne (2014) fears that increased preventative surveillance could lead to increased contact with the criminal justice system, which she found led to a greater effort by individuals to avoid prosocial surveilling institutions, like hospitals, banks, schools, and jobs.

Still, as sentinels, Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. (2015) argue that police may be able to have a deterrent effect if they can increase the probability of apprehension to the point where a target becomes unattractive to a potential offender, which does not have to involve increased arrests. Consistent with Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin (2015), scholars (Reference Cullen and PrattCullen and Pratt 2016; Reference Welsh and FarringtonWelsh and Farrington 2012) recognize that policing could be a better alternative to incarceration as long as there is a focus on the front end, and not just solving crimes “after the fact.” To our knowledge, there are no previous studies that have explored public preferences for whether police should focus more on solving crimes or patrolling the streets. Therefore, it remains unclear whether Americans would be supportive of the style of policing advocated by deterrence scholars which prioritizes the sentinel role over the enforcement role.

Concentrating on Crime Hot Spots

The evidence to date suggests that concentrating police resources in small areas of cities with higher levels of crime, or “hot spots,” may be an effective method of crime reduction, at least when certain types of intervention strategies are used (Reference Braga, Papachristos and HureauBraga et al. 2012; Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015; Reference Weisburd and EckWeisburd and Eck 2004). According to Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. (2015), police can be most effective in their sentinel role when targeting these hot spots. Hot spots policing, though, encompasses many different strategies, some of which appear to be more effective than others in reducing crime (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011).

One hot spots policing strategy involves the use of aggressive order-maintenance policing. This form of policing, commonly referred to as “broken windows” or “zero tolerance” policing, is based on the theory of Reference Wilson and KellingWilson and Kelling (1982) that physical disorder and “public nuisances” in the community can create an environment conducive to serious crime (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015: 12). It focuses on increasing arrests for minor forms of offending as a means of alleviating disorder within the community. These tactics are a key part of stop, question, and frisk (SQF) programs, which were made popular by the New York City Police Department and scaled back due to findings of unconstitutionality in execution (Reference SweetenSweeten 2016). Many have identified SQF as “unethical, damaging to minority communities,” and “ineffective because of the poor police-citizen relations it produced” (Reference SweetenSweeten 2016: 68), while fueling mass incarceration. Empirical research also indicates “broken windows” policing is less effective than other strategies designed to decrease criminal opportunities (Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond 2008; Reference Braga, Welsh and SchnellBraga et al. 2015; Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015; Reference Peters and EurePeters and Eure 2016).

Another strategy, although less commonly used in hot spots, is offender-focused policing. Also sometimes identified as “focused deterrence” or “pulling levers,” offender-focused policing concentrates on regularly monitoring known offenders in the community. This strategy is based on research suggesting that a small percentage of offenders are responsible for the majority of the crimes committed, meaning these offenders have a substantial impact on the crime rate (Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015; Reference Wolfgang, Figlio and SellinWolfgang et al. 1972). While some studies have found a significant impact of focused deterrence strategies on crime reduction (Reference Braga and WeisburdBraga and Weisburd 2012; Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015), others still report a limited effect of offender-focused interventions (e.g., Reference Santos and SantosSantos and Santos 2016).

A third strategy for policing hot spots involves simply increasing police patrols in the area. Based on deterrence theory, police agencies rely on patrols, whether by foot, car, or bicycle, as a method of providing more localized police presence (Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015). Two recent studies reported violent crime reductions as a result of increased patrol (Reference Piza and O'HaraPiza and O'Hara 2014; Reference RatcliffeRatcliffe et al. 2011), with Reference Ariel, Weinborn and ShermanAriel et al. (2016) even finding reduced crimes and calls for service using “soft” patrols of civilian police officers who do not carry firearms or weapons but increase police presence. Also, increased car patrols, as well as patrols requiring engagement of the police officer in activities like arrest, pedestrian checks, or building checks, at 15 minute intervals can reduce crime incidents (Reference Rosenfeld, Deckard and BlackburnRosenfeld et al. 2014; Reference Telep, Mitchell and WeisburdTelep et al. 2014). However, additional research found foot patrols to be ineffective in comparison to other forms of policing (Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015) and that offenders can learn the patterns and timing of increased patrol in certain areas and adjust their behavior accordingly (Reference Ariel, Weinborn and ShermanAriel and Partridge 2016).

A final leading hot spots intervention strategy involves situational prevention. Situational prevention is tied to the theory of Reference Wilson and KellingWilson and Kelling (1982), but focuses more on reducing disorder through the adjustment of the physical or social environment in high crime areas (e.g., improving street lighting, adding video cameras, tearing down abandoned buildings, performing code inspections), as opposed to increasing arrests for minor forms of offending (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015). This strategy mitigates criminal opportunities in hot spots and reduces the likelihood of offending (Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond 2008; Reference ClarkeClarke 1997). Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond (2008) identified situational prevention as the hot spots intervention strategy that had the greatest crime-control gains when compared to increased misdemeanor arrests and social service strategies in their experimental study.

We are not aware of any previous studies that have explored public support for hot spots policing, or examined citizens’ preferences for different ways to police hot spots. It is also unknown whether such support varies across demographic groups, which is theoretically anticipated, and if the public prefers certain hot spots intervention strategies more than others.

Data and Methods

The primary objective of our study is to obtain accurate prevalence estimates of Americans’ cost-effectiveness judgments and attitudes toward sentinel and hot spots policing. Toward this end, we commissioned the GfK Group (formerly Knowledge Networks) to administer a series of survey questions on policing to adult (18 and older) members of the American public. GfK selected a sample of survey respondents from its probability-based “KnowledgePanel Omnibus,” and carefully designed the web-enabled panel to be representative of the U.S. population. GFK initially recruited panelists through random selection of telephone numbers and residential addresses. To extend coverage to Americans who are not Internet users, they provide laptop computers and Internet access to all panelists who need it. Surveys are then periodically e-mailed to panelists, and are self-administered through the respondents’ (or the GfK-provided) computers.

GfK Custom Research, LLC is the market leader for probability-based Internet surveys of the general U.S. population (Reference Weinberg, Freese and McElhattanWeinberg et al. 2014), and academic researchers frequently use data from the KnowledgePanel (Reference Craig and RichesonCraig and Richeson 2014a; Reference Donovan and KlahmDonovan and Klahm 2015; Reference Krosnick, Malhortra and MittalKrosnick et al. 2014). Indeed, the Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences, an ongoing interdisciplinary program funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to field experiments with general population samples (Reference MutzMutz 2011), and the American National Election Studies have used the GfK KnowledgePanel for many years. Reference AllcottAllcott (2011) opines that “Knowledge Networks [now GfK]… maintains perhaps the highest-quality publically available survey platform.” Consistent with this view, Reference Chang and KrosnickChang and Krosnick (2009) show that GfK surveys manifest “the optimal combination of sample composition accuracy and self-report accuracy” (641). Specifically, GfK surveys yield higher quality data—with less random measurement error, satisficing, and social desirability bias—than random telephone surveys, without sacrificing representativeness. Likewise, Reference YeagerYeager et al. (2011) examined the accuracy of GfK's probability-based web panel surveys, and found that these “probability samples, even ones without especially high response rates, yielded quite accurate results” (737).

GFK fielded the omnibus survey over the course of three days in the Spring of 2016. They sent one reminder e-mail during the administration period. Of the panelists who were invited to take part in the survey, 29.5 percent participated to obtain a sample of close to 1,000 respondents.Footnote 2 Meta-analytic research shows that nonresponse rates in surveys are generally uninformative about data quality or nonresponse bias (Reference GrovesGroves 2006; Reference Groves and PeytchevaGroves and Peytcheva 2008). A recent report on survey research methods to the NSF emphasizes this point: “nonresponse bias is rarely notably related to [the] nonresponse rate” (Reference KrosnickKrosnick et al. 2015: 6). In our study, we are unconcerned about nonresponse bias for three reasons. First, the majority of nonresponse occurred before respondents encountered the questionnaire (e.g., at initial recruitment in the panel), and thus is unlikely to be directly related to survey content. Second, this type of nonresponse—prior to encountering the survey topic or questions—is most likely to be a function of respondent demographics (e.g., race, income), and using post-stratification weights for these demographics, as we do (see below), should address concerns with nonresponse bias related to these factors (Reference Groves and PeytchevaGroves and Peytcheva 2008). Third, there is strong evidence that low response rate probability samples, like ours, provide highly accurate prevalence estimates (Reference Dutwin and BuskirkDutwin and Buskirk 2017; Reference YeagerYeager et al. 2011).

The margin of error for the full sample is ±3 percentage points. In all the analyses presented, we weight the data to account for the probability of selection, and to match population benchmarks from the U.S. Census and Current Population Survey.Footnote 3 The unweighted and weighted demographic characteristics for all respondents in the sample with complete data on the respective demographic items are shown in Table 1.Footnote 4

Table 1. Unweighted and Weighted Descriptive Statistics

Measures

There are four survey questions of interest in our study. In the design of these questions, we had two main goals. First, we understood hardly any respondents would be well-versed in the current debates surrounding policing. Therefore, in the question stem, we briefly introduce each of the issues asked about in order to familiarize respondents with the various topics (see questions below). In so doing, we followed a similar approach as used in prior studies (Reference Manza, Brooks and UggenManza et al. 2004; Reference ThieloThielo et al. 2016), keeping introductions minimal and neutral so as to avoid biasing answers or creating artificially knowledgeable opinions. Additionally, we avoided the use of Likert-scale responses to prevent satisficing among respondents (Reference Pickett and BakerPickett and Baker 2014). Instead, the respondents were provided item-specific questions (Reference SarisSaris et al. 2010) and asked to make clear choices between balanced alternatives.Footnote 5

The first question measures respondents’ judgments about the cost-effectiveness of spending on prisons versus policing. As noted above, one leading suggestion for how to downsize prisons without increasing crime is to redirect some of the funds used to incarcerate offenders for long time periods to policing (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011), which appears to be a more cost-effective policy option for controlling crime (Reference Chalfin and McCraryChalfin and McCrary 2013; Reference Lofstrom and RaphaelLofstrom and Raphael 2013, Reference Lofstrom and Raphael2016; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014). To investigate public views about this issue, we presented respondents with the following survey question, which is similar to prior studies by Cohen and colleagues regarding the willingness to pay for crime control alternatives (Reference CohenCohen et al. 2004, Reference Cohen, Rust and Steen2006):

We are interested in your views about the cost effectiveness of two different approaches to controlling crime. We want to know which approach you think provides the greatest crime control benefit for EACH dollar spent. That is, which provides the most “BANG FOR THE BUCK.” Of the following, which do you think prevents the most crimes: (1) Each dollar spent to keep convicted criminals in prison, or (2) Each dollar spent on policing?

The next outcome variable in our study measures respondents’ preference for whether police officers should focus primarily on their role as apprehension agents or sentinels; that is, whether they should concentrate on enforcement or prevention (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015). The following survey question was used:

We are interested in your beliefs about where police officers should focus their attention to best control crime. Which of the following comes closest to your view? (1) Police officers should focus primarily on SOLVING CRIMES that have already been committed, or (2) Police officers should focus primarily on PATROLLING the streets to prevent new crimes.

The final two outcome variables measure views about hot spots policing. The first of these variables measures respondents’ overall support for hot spots policing. Here, we are interested in whether Americans have favorable or unfavorable attitudes toward efforts to concentrate police activities in hot spots, even if it means that fewer resources are available for policing lower-crime areas. It is conceivable, for example, that the general public may be concerned that hot spots policing could lead to discrimination and/or the underpolicing of other areas. The survey question was:

Statistics show that most of the crimes that are committed in cities happen in a few small areas, such as city blocks, known as “hot spots.” However, police departments have a limited number of officers and resources. Do you think the police should focus more on policing hot spots than other areas, or focus on policing all areas equally?

Next, we inquired about the respondents’ preferences for how hot spots policing should be carried out. Specifically, we asked respondents to rank order four of the leading hot spots policing strategies: aggressive order-maintenance policing (i.e., making more misdemeanor arrests), offender-focused policing, increased police patrols, and situational interventions (i.e., modifying the environment) (Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond 2008; Reference GroffGroff et al. 2015). The survey question is listed below. Per the recommendations of Reference Dillman, Smyth and ChristianDillman et al. (2014:146, 240), we randomized the order in which the policing strategies were presented to respondents to minimize any potential ordering effects, such as primacy or recency effects.

Again, “hot spots” are small areas in cities where there is a lot of crime. There are different approaches that can be used to police “hot spots.” Please rank the following approaches from the one you MOST support (1) to the one you LEAST support (4): (1) Make more arrests in hot spots for minor offenses, such as public drinking, to get offenders off the street, (2) Regularly monitor known offenders, such as gang members and drug dealers, in hot spots, (3) Increase police presence and patrols in hot spots, (4) Modify the environment in hot spots by improving street lighting, adding video cameras, tearing down abandoned buildings, etc.

In the multivariate models, we also include independent and control variables that prior research suggests may be related to attitudes toward policing. Previous studies find that age, race, political ideology, and education are predictive of views about police policies (Reference JohnsonJohnson et al. 2011; Reference PickettPickett 2016; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer and Tuch 2006). Other studies suggest that criminal justice attitudes often vary by gender, family status, socio-economic status, and region of residence (Reference Barkan and CohnBarkan and Cohn 2010; Reference BaumerBaumer 2003; Reference SilverDenver et al. 2017; Silver 2017). Research finds similar predictors of views about different approaches to crime control (Reference Cohen, Rust and SteenCohen et al. 2006). For this reason, we include measures of these various factors in the models.

Results

Figures 1 and 2 present the weighted results for the full sample. We first consider the public's evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of spending on prisons versus policing. Inspection of Figure 1 shows that a majority of Americans (68 percent) believe that each dollar spent on policing prevents more crimes than each dollar spent to incarcerate offenders. Results from supplementary analyses in which we disaggregated the sample by respondent characteristics (not shown) revealed that a majority of every major demographic group—blacks, Hispanics, Whites, males, females, younger and older persons (defined by median), those with and without college education, those with low and high incomes (defined by median)—perceived that policing is more cost effective than prisons. Specifically, when the sample is disaggregated, between 56 percent and 75 percent of each major demographic, political, and regional group sees policing as more cost effective (not shown). This majority belief in the relative cost-effectiveness of policing emerged in every political group—Republicans, independents, and Democrats—and region—Northeast, South, Midwest, and West. Given extant evidence about the cost-effectiveness of different criminal justice policy options (Reference Chalfin and McCraryChalfin and McCrary 2013; Reference Lofstrom and RaphaelLofstrom and Raphael 2013, Reference Lofstrom and Raphael2016; Reference RaphaelRaphael 2014), our findings indicate that the public view aligns with research suggesting that spending on policing offers more “bang-per-buck” than spending on incarceration.

Figure 1. Americans’ Views About the Cost-Effectiveness of Policy Options for Controlling Crime and Policing Preferences. Notes: Across the three questions, the sample size ranges from 965 to 977 because of item nonresponse.

Figure 2. Americans’ Preferred Hot Spots Policing Strategy (N = 955).

Next, we focus on Americans' preferences for whether police should concentrate more on enforcement—the apprehension-agent role—or prevention—the sentinel role. As previously discussed, many scholars have argued that there is a need to fundamentally change policing to concentrate less on solving crimes and more on patrolling streets to prevent new crimes (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015), although others question this advice (Reference Pickett and RochePickett and Roche 2016). The data presented in Figure 1 show that the public overwhelmingly agrees that police should focus primarily on their sentinel role. Fully, 76 percent of the sample prefers that police focus more on patrolling the streets to prevent new crimes than on solving crimes already committed. When the sample is disaggregated, between 69 percent and 83 percent of each major demographic, political, and regional group prefers sentinel-style policing (not shown).

Our focus now turns to exploring public support for hot spots policing. As shown in Figure 1, the majority of Americans (61 percent) prefer police to concentrate more heavily on policing hot spots than other areas. Disaggregated analyses (not shown), revealed that although a majority of most groups prefer hot spots policing, there are some demographic cleavages. Specifically, only a minority of blacks (46 percent), Hispanics (40 percent), and persons without a college education (49 percent) support hot spots policing. Stated differently, in these demographic groups, the majority of individuals prefer that all areas in cities receive equal policing. We will explore these demographic differences in greater detail below.

Figure 2 presents Americans’ preferences regarding the leading strategies for hot spots policing. Again, we asked respondents to rank order the four strategies. In Figure 2, we show the percent of the public choosing each strategy as their top choice, as well as the percent of blacks and whites choosing each strategy.Footnote 6 By far, the hot spots policing strategy Americans prefer most overall is situational interventions (41 percent), and the least supported strategy is aggressive order-maintenance policing (8 percent). Notably, extant research suggests that the former is more effective at reducing crime in hot spots than the latter (Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond 2008). Thus, the most publically supported hot spots policing strategy is also among the most empirically supported. When the sample is disaggregated by overall support for hot spots policing, situational interventions emerge as the most preferred strategy among both respondents who want police to focus on hot spots, and among those who want police to focus equally on all areas. The implication is that when implementing hot spots policing, using situational interventions may be important for increasing receptivity among those persons who are initially the least supportive of hot spots policing. Additional analyses demonstrated that the general ranking of strategies seen for the full sample—that is, situational interventions being most preferred, followed by foot patrols, offender-focused policing, and then aggressive order-maintenance policing—emerges in every major demographic and political group, with two exceptions. As noted in Figure 2, the most preferred hot spots policing strategy among blacks is increased patrol, followed by situational interventions. The same pattern of support emerges for Republicans as well.

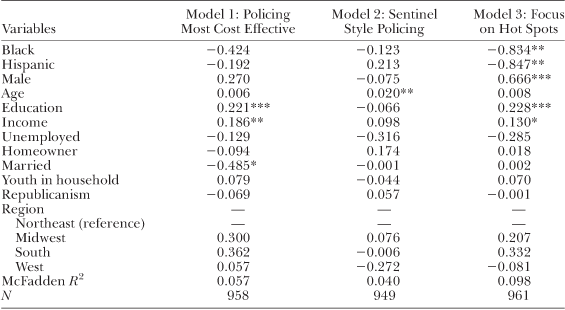

The final portion of the analysis further explores whether there are important demographic, political, and regional differences in public evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of policing and policing preferences. Tables 2 and 3 report the results from a series of logistic and multinomial logistic regression models that control for respondents’ demographic characteristics, political party identification, and region of residence. Very few factors are significantly associated with views about the relative cost-effectiveness of policing or preferences for sentinel- versus enforcement-style policing. Most notably, respondents with higher levels of education and income are significantly more likely to believe that policing is more cost-effective than prison. Married persons appear to be less likely to hold this view. Only age is a significant predictor of preferences for an enforcement- versus preventive-style of policing. Specifically, older persons are more likely than their younger counterparts to prefer sentinel-style policing.

Table 2. Logistic Regression Models Predicting Americans’ Views about the Cost Effectiveness of Crime Control Policies and Preferences for Police Policy

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

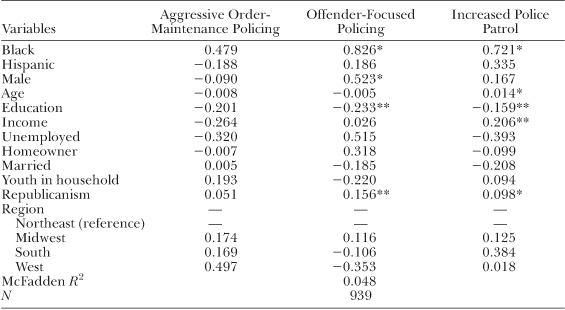

Table 3. Multinomial Logistic Regression Predicting Americans’ Preferences for Hot Spots Policing Strategies

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001 (two-tailed).

Notes: The base outcome indicates those who prefer situational interventions.

By contrast, there are several notable findings for views about hot spots policing. Blacks and Hispanics are significantly less likely than other racial and ethnic groups to support hot spots policing. This perhaps reflects a concern among these minority groups that hot spots policing may lead to discrimination by the police against minority neighborhoods or may aggravate grievances toward the police already existing in these neighborhoods (Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin 2015). The data also show that gender, education, and income are associated with views about hot spots policing. Specifically, males and persons with higher levels of education and income are all more likely to support hot spots policing. The effects of education and income may reflect a concern among persons with lower socioeconomic status that hot spots policing could result in the overpolicing of poorer neighborhoods—the types of neighborhoods in which they are probably more likely to reside.

Table 3 presents the results for preferred type of hot spots policing strategy. We use situational prevention as the reference category in the multinomial logistic regression. The results suggest that relative to other racial and ethnic groups, blacks are significantly more likely to prefer offender-focused policing or increased patrol. Males are more likely than females to prefer offender-focused policing. Being older or having higher income is associated with a higher likelihood of preferring increased patrols. By contrast, having higher educational attainment increases the likelihood of preferring situational interventions. Finally, Republicans are more likely than members of other political parties to prefer offender-focused policing or increased patrols over situational interventions.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this study, we set out to evaluate public sentiments regarding the cost-effectiveness of policing versus prison, sentinel style policing, and hot-spots policing as a means of determining whether the public would be supportive of the recent recommendations for effective crime control in the era of prison downsizing. Our motivation for exploring public views stemmed from the fact that unwanted shifts in policing could erode the perceived legitimacy of the police among the public and policy makers are largely responsive to the public's interests. Overall, we found that the majority of the public in virtually every demographic, political, and regional group believes policing is more cost-effective than keeping convicted criminals in prison, favors sentinel style policing over enforcement, and supports focusing more resources on hot spots, even if less resources are being devoted to other areas. We also found that the public is most supportive of situational prevention in hot spots, followed by increased patrols, offender-focused policing, and aggressive order-maintenance policing. Together, this evidence suggests that the majority of the general public would be receptive to each of the proposed changes in crime control policy.

Despite this conclusion, there are three concerns that should be noted with regard to hot spots policing. First, we found that blacks and Hispanics, as well as those with lower incomes and education, were less supportive of devoting more resources to hot spots policing and preferred policing all areas equally. While we did not ask questions to shed light on this lack of support, we can speculate some reasons. Many of the areas classified as hot spots are home to low income minorities. Within the context of racial and ethnic threat, it is not surprising that higher income whites support crime control policies targeting minority neighborhoods at higher levels. It appears that low income minorities may not be receptive to a change in police strategy that would bring more attention to their communities. As stated previously, trust and confidence in the police is lower among minorities (Reference Sunshine and TylerSunshine and Tyler 2003; Reference TylerTyler 2004; Reference Weitzer and TuchWeitzer and Tuch 2006), and a transition to increased policing in the areas predominantly occupied by low income minorities may aggravate the already tenuous police-community relations, thereby eroding the legitimacy of the police further in these communities. When the police are seen as less procedurally just and less legitimate, this can affect the public's willingness to cooperate with the police and comply with the law (Reference Murphy, Hinds and FlemmingMurphy et al. 2008; Reference Reisig, Tankebe and MeškoReisig et al. 2012). It can also foster legal cynicism and estrangement within the community, which has been tied to increased homicide rates in neighborhoods (Reference BellBell 2016; Reference Kirk and PapachristosKirk and Papachristos 2011).

Blacks and Hispanics may also fear possible discrimination toward minority neighborhoods with the implementation of hot spots policing, a circumstance not so far removed from the era of mass incarceration that disproportionately targeted blacks (Reference AlexanderAlexander 2012; Reference TonryTonry 2011; Reference Van Cleve and MayesVan Cleve and Mayes 2015; Reference WacquantWacquant 2002). Hot spots policing can be potentially damaging to the communities it targets (Reference KochelKochel 2011) and can undermine collective efficacy and social control in neighborhoods (Reference Rosenbaum, Weisburd and BragaRosenbaum 2006). These communities become subject to “territorial stigmatization,” and are labeled as “lawless” and uninhabitable (Reference WacquantWacquant 2007). It is not uncommon to use targeted strategies, like hot spots policing, in these areas, but these efforts can further marginalize the people living in them (Reference BrayneBrayne 2017; Reference WacquantWacquant 2007: 69). Alternatively, it is quite possible that minority respondents may not feel their communities are disproportionately targeted, but rather, that they are currently under-policed. In this regard, they may prefer more equal policing to restore the status quo and responsive government services to all areas. Reference RiosRios (2011) recognizes this idea as an “overpolicing-underpolicing paradox,” such that the police are a looming presence in the lives of many marginalized groups, but they are often not present to protect them when needed (54). Whatever the reason for the lack of support among low income minorities, when considering hot spots policing as an alternative strategy to incarceration, policy makers should account for the consequences in the communities they target and among the people who live in them.

Second, we found that Republicans and those of higher income support increased foot patrols over situational interventions. This support aligns with the ideals of racial threat, in that increased foot patrols in hot spots represents a mechanism of social control in lower income, minority areas. However, we were surprised to find that blacks also support increased foot patrols as the preferred method in hot spots. Recent research suggests that blacks often face competing pressures to oppose policies that can lead to discrimination on the one hand and support policies that control crime in their neighborhoods on the other (Reference RamirezRamirez 2014, Reference Ramirez2015). Residents of high crime areas often want more aggressive forms of policing to restore order, at least until this aggressive enforcement affects them or their families (Reference Rosenbaum, Weisburd and BragaRosenbaum 2006). We find these polarizing opinions as well, such that blacks are less supportive of focusing more police resources in hot spots—likely due to the increased potential for discrimination—but among hot spots policing strategies, favor interventions more focused on ensuring access to the police.

Third, respondents reported the least support for strategies involving increasing arrests for minor offenses in hot spots. Public sentiments thus align with existing research demonstrating that increased misdemeanor arrests is not an effective method of reducing crime (Reference Braga and BondBraga and Bond 2008; Reference Peters and EurePeters and Eure 2016). Given the lack of public support and evidence for this method of policing, which emphasizes enforcement over prevention, policy makers should consider allocating more resources toward strategies favored both publically and empirically, such as situational prevention. Given its low levels of support, “zero tolerance” policing may actually damage police-community relations by decreasing the perceived legitimacy of the police (Reference Gau and BrunsonGau and Brunson 2010; Reference Schulhofer, Tyler and HuqSchulhofer et al. 2011; Reference SweetenSweeten 2016). It is likely that the public views these tactics as procedurally unjust. As Reference Lum, Nagin and TonryLum and Nagin (2015) recognize, such activity depends to a large extent on discretion and can “introduce bias, inequity, illegality, or questionable practices into policing” (12). Situational interventions represent more of a “criminology of the self” that characterizes crime as normal and focuses on mechanisms of control that eliminate opportunities for crime, as opposed to a “criminology of the other” that marginalizes a particular group (Reference GarlandGarland 2001). The public supports focusing on the former in hot spots. It is ideal for minority groups that may feel disproportionately affected by hot spots interventions, because situational intervention is a less targeted approach. Although the current administration favors law and order approaches, it would be worthwhile to consider the public's view of “zero tolerance” policing and the consequences of its implementation to the legitimacy of the criminal justice system.

There is, however, a need for more evaluation studies of hot spots policing, including the various methods of implementation. Based on the existing evidence, resources should be devoted primarily to situational prevention, which aligns with public interest, and offender-focused policing, which is less favored by the general public. A lot of this research, though, suffers from various limitations. In their meta-analysis of problem oriented policing, Reference WeisburdWeisburd et al. (2010) were surprised to find only 10 studies with the appropriate methodological rigor to meet their inclusion criteria. Similarly, Reference Braga, Papachristos and HureauBraga et al. (2012) found only 16 eligible studies for their meta-analysis of hot spots policing, and Reference Braga and WeisburdBraga and Weisburd (2012) identified 11 eligible studies in their meta-analysis of focused deterrence. Also, for most of the policing strategies, there is not a sufficient number of studies to make informed comparisons across the different types of interventions (e.g., Reference WeisburdWeisburd et al. 2010). An increase in evaluation studies is needed to gain a better understanding of the more effective police policy approaches (Reference WeisburdWeisburd et al. 2010) and to identify whether certain policies are more effective within “well-defined sets of circumstances” (Reference Cullen and PrattCullen and Pratt 2016; Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011: 43).

It is important to consider our findings in the context of the existing debate in the field regarding the merits of the current recommendations for reforming policing. Recent research questions the strength of the evidence for hot spots policing, and argues that there is no evidence that police numbers or activities can influence crime rates by increasing the perceived arrest risk (Reference Pickett and RochePickett and Roche 2016). Reference Cullen and PrattCullen and Pratt (2016), however, emphasize that there are several other mediating mechanisms, besides sanction perceptions, through which police may be able to influence crime rates. Reference KleckKleck (2016) suggests that there may be more displacement from sentinel and hot spots policing interventions than is presently recognized, especially if offenders begin searching for targets in areas beyond the immediate vicinity of the intervention. He argues that stronger controls for displacement are needed in policing research. The contribution of our findings to this debate is twofold. First, our study shows that the public strongly supports those policing strategies that currently have the greatest empirical support, even if we accept that the strength of the empirical evidence is less than ideal and the mechanisms linking policing and crime are unclear. Second, our findings add urgency to the need for more methodologically rigorous evaluation research. If future studies address the limitations in existing research and yet still come to the same conclusions as past studies, policy makers would face an ideal situation. Specifically, in every instance—the cost-effectiveness of policing, sentinel-style policing, hot spots policing, and situational prevention in hot spots—there would be a strong reservoir of public support for evidence-based police reforms.

At the same time, it should be clear that public support for the various policing strategies identified does not imply that policing is the only cost-effective alternative to prison. We focused on policing in light of the recent discussions and debates among scholars surrounding the allocation of more resources to policing (Reference Cullen and PrattCullen and Pratt 2016; Reference KleckKleck 2016; Reference NaginNagin 2016; Reference Nagin, Solow and LumNagin et al. 2015; Reference Pickett and RochePickett and Roche 2016). Additionally, we believe this is an area where the public would be most impacted. However, while Reference RaphaelRaphael (2014) calls attention to the potential crime benefits of increased policing, he indicates that “the efficient, or lowest cost, policy strategy would be that for which our various policy tools are employed to the point where the marginal benefit in terms of crimes prevented for each additional dollar spent was equal across all possible interventions” (589, emphasis added). This statement implies that multiple interventions, not just policing, could produce an overall benefit in crime reduction. Reference RaphaelRaphael (2014) and others (Reference Durlauf and NaginDurlauf and Nagin 2011; Reference Welsh and FarringtonWelsh and Farrington 2012) discuss the potential benefits of early childhood education, for instance, as a possible intervention. Evidence indicates that early family and parenting training can effectively reduce behavioral issues among younger children, and delinquency and crime in adolescence and adulthood (Reference PiqueroPiquero et al. 2009). Studies also show that the public is both supportive of and willing to pay for early intervention and rehabilitation (Reference BakerBaker et al. 2015; Reference Cohen, Rust and SteenCohen et al. 2006; Reference ThieloThielo et al. 2016). Therefore, we should not preclude a reallocation of resources from prison to early childhood education as an additional policy tool.

We also acknowledge that the questions asked are imperfect measures. While the questions achieved our goals of introducing the respective policies and minimizing stylistic responding, we are only able to provide single item indicators of the policing reforms considered. We also recognize, as with all public opinion research, that responses could be an artifact or “illusion” of question wording and the response choices provided (Reference BishopBishop 2005). For example, responses may have been different if the answer choices included other cost-effective alternatives, aside from policing. The reliability of the measures would be further increased by using additional indicators that ask respondents about these reforms in various ways, through repeated studies measuring these concepts, and with the introduction of more response choices.

Also, some argue the general public does not have well-developed opinions regarding the questions asked (Reference BishopBishop 2005) and more deliberative questioning than we presented would lead to more informed responses. However, two relevant points bear mention. First, there is a larger literature showing that members of the public often formulate their attitudes toward criminal justice policies intuitively, and that these “intuitions of justice” nonetheless are substantively meaningful and have important implications for legal legitimacy (Reference RobinsonRobinson 2008; Reference Robinson and DarleyRobinson and Darley 2007). Second, de Reference De Keijser, Ryberg and RobertsKeijser (2014) argues that “deliberative polling techniques measure attitudes of a hypothetical public” whose views are only temporary, often reverting back “to general public opinion after some time has passed” (107).Footnote 7 The legitimacy argument we present for studying public opinion is actually most relevant to the intuitions of the uninformed general public, who will be responding and reacting to these policing changes in real time with little knowledge in the area (Reference De Keijser, Ryberg and Robertsde Keijser 2014). Even given the existing limitations, the study provides an initial look at public preferences regarding contemporary developments in policing, as well as potential public reactions to significant shifts in policing, both of which are relevant to policy makers and practitioners in the current crisis of confidence within policing.