What is a phōtistērion? You will not find this word in a standard English dictionary, or even in a specialised dictionary about religion, or even in a more specialised dictionary about early Christianity. To find phōtistērion as a dictionary headword, you would need the hyper-specialised Liturgical dictionary of eastern Christianity, which defines it as: ‘Literally, a “place of enlightenment”. An archaic word used to describe the rite of baptism and the baptistery. See BAPTISTERION.’Footnote 1 The supposed substitutability of one term for another is presumed throughout scholarly literature as well: phōtistērion is no more than another word for baptistery. Again and again, this Greek word for a ‘place of enlightenment or illumination’ is substituted by a word designating a ‘place of going under water’.Footnote 2 If the Greek original is not provided, the reader of the translation has no idea of this shift in the figurative language.

A sceptical reader might already be thinking, ‘So what? Both words mean the same thing.’ First, this essay makes the case that this word is worth some attention and that we might not already know what it means; second, it presents the main examples of phōtistēria; and third, it explains several different ways in which the terminological difference is meaningful for our understanding of early Christian liturgical practice and sacramental theology. In the end, the evidence from late antiquity shows that ‘baptistery’ is a misleading translation of phōtistērion, since Christians who built and used phōtistēria probably imagined ‘illumination’ to express the composite rites of initiation, within which ‘baptism’ was only one part.

Metaphors, by which we live

Interest in this topic came through prior research on the third-century house-church from Dura-Europos, Syria, and especially its unique room for Christian initiation.Footnote 3 In publications on that topic I do use the word ‘baptistery’, but I have constantly wondered whether that is what the initiates in that building would have called it. I think it is more likely they would not have used that word but, sadly, there is no inscription that names the room. So I used ‘baptistery’ grudgingly – an imperfect choice, but one that effectively communicated ‘specialised room for Christian initiation’ in modern terminology.

During that previous research, investigation of inscriptions from the region that named the various rooms of late ancient churches led to one curious discovery which specifically launched this current project. In north-western Galilee, at a kibbutz in ‘Evron near Nahariya, there are foundations and partial mosaic floors from a little-known early Byzantine church. One of the surviving inscriptions gained some fame for its use of the Hebrew letter yod three times (the first letter of the divine name), probably to signify the divine Trinity. But of interest for our purposes is an inscription that dedicates the renovation of the church's phōtistērion. It is a unique example in the extant corpus because this inscription is in a different room from the one which contains the basin for water baptism. As described by Michael Avi-Yonah, ‘by some unexplained mistake the inscription referring to the “place of light [photisterion, i.e. the baptistery]” was found in one room, and the fount in another’.Footnote 4 Avi-Yonah's comment assumes that phōtistērion and baptistery must have the same referent, and that the inscription in an adjacent room was thus ‘some unexplained mistake’. However, what if the term phōtistērion designated something else, something different or larger than the room where the font was? What would give modern archaeologists the confidence to claim that a mosaic inscription – requiring time, money, planning and artisanship – would mistakenly label the wrong room? Or was this a peculiar aberration, a local term that was not in use elsewhere? Or, for some Christians in late antiquity, did phōtistērion really mean something other than the room for baptism?

Without further evidence, the disjunction between this phōtistērion inscription and the font in the next room remains unexplained. But Avi-Yonah's identification of the issue invites further examination of the available phōtistēria from the region, located in Galilee, Syria, Jordan and (probably) Cyprus. The contention of this article is that the liturgical signifiers of water and those of light should not be so quickly elided.

The unwitting conflation of these two different terms is surprising in a field full of philologists and metaphorically-knowledgeable interpreters. The power of metaphors to shape our thinking, even to delimit the boundaries of possible thoughts, is well understood. G. Lakoff and M. Johnson's classic, Metaphors we live by, has demonstrated how much meaning is carried through language surreptitiously, depending on the metaphors chosen – or rather, not consciously chosen – by those doing the talking.Footnote 5 Ideas are food; arguments are war; love is a force of physics; theories are buildings. These are just a few conceptual metaphors identified by Lakoff and Johnson that undergird the English language, as the hidden infrastructure of our thought. Conceptual metaphors such as these, because they are used without the feeling of having thought about them, can limit the extent and predetermine the meanings of possible thought on a topic.

Indeed, regarding the crucial roles played by metaphor in determining interpretation, scholars of early Christianity are quite conscientious in certain fields of discourse. Consider the fine distinctions drawn within the realms of Christological language. Historians and theologians rightly differentiate the meanings and valences of titles and metaphors used to express the mystery of divinity and humanity in Jesus Christ: Son, Lord, Begotten, Adopted, Light, Word, Wisdom, Radiance, Emanation, King, Shepherd. We do the same careful work with figurative language about salvation, knowing that each image carries with it a particular history and specific contextual connotations: sacrifice, victory, ransom, redemption, exaltation, reconciliation, cleansing, knowledge. If an ancient source said that Christ was begotten from the Father, we would never translate that as an ‘adoption’. We stake strong claims on distinguishing Logos / Word from Sophia / Wisdom. If a Greek text calls Christ a ἱλαστήριον, the term would not be translated as a ‘cleansing’ or a ‘victory’; the sacrificial imagery of that metaphor would in some way be retained.

In Christology and soteriology scholars are appropriately fastidious about figurative language, but for source texts concerning initiation, phōtismos is regularly translated as ‘baptism’, phōtizomenoi as ‘candidates for baptism’, neophōtistos as ‘newly baptised’, and phōtistērion as ‘baptistery’. It is as if in Christology the choice had been made to conflate the Greek words for ‘king’ and ‘shepherd’ by translating them all as ‘king’. To be sure, there are some contemporary scholars who are careful in distinguishing images of initiation, such as Maxwell Johnson, Robin Jensen and others.Footnote 6 And the classic study of Greek baptismal terminology does devote an entire chapter to interpreting phōtismos on its own terms.Footnote 7 Overall it is customary to read about a church's ‘baptistery’ and its ‘newly-baptised’, but if the Greek is checked the words for light are revealed. The light of Christian initiation is thus hidden under a bushel – or rather, under a font.

This essay asks us to reconsider the practice of translating words for ‘illuminating something with light’ with words that refer to ‘dunking something in water’. Then, what happens to the meaning if we stop doing so?

Linguistic and archaeological evidence for phōtistēria

What is the linguistic and archaeological evidence for phōtistēria and baptistēria? In the Thesaurus linguae graecae, an extensive database of Greek literature, the quantitative evidence for both words is sparse. But the word phōtistērion, which seems prima facie to be more obscure, actually occurs more often than baptistērion, the cognate for what became the more common word in English and some other modern Western languages.Footnote 8 This would be surprising enough for casual users of the word ‘baptistery’, but the evidence from Greek inscriptions tells an even more dramatic story. The Packard Humanities Institute's database of Greek inscriptions, which is an extensive, albeit incomplete, collection of published inscriptions from antiquity and late antiquity, contains only two examples of baptistēria.Footnote 9 By contrast, the database has at least eleven clear examples of the word phōtistērion from Galilee, Syria and Jordan in the fifth through seventh centuries; and two more probable examples would would bring the total count to thirteen.Footnote 10

What is more, this tally of names for sites of initiation does not include at least sixteen examples of individuals called neophōtistos in inscriptions, while there are no examples of neobaptistos. In the Thesaurus linguae graecae, that difference is even more stark: there are 146 uses of neophōtistos through the seventh century, and no examples of neobaptistos. Contrary to this evidence from literary and epigraphic sources, G. W. H. Lampe's lexicon for patristic Greek reveals an English translator's bias toward ‘baptism’ language, even amid the prevalence of ‘illumination’ language. Though it does use ‘newly illuminated’ as the first translation of neophōtistos and confirms that the term retains ‘the idea of illumination’, it then proceeds to use ‘baptised’ or its cognates seven times in the rest of the dictionary entry, while words for light never appear again.Footnote 11 In general, Lampe claims, the word is used as a ‘synonym’ for neobaptistos, which leads the reader to assume that neobaptistos is the more common word. Yet the great twentieth-century lexicographer could find only scarce, obscure and very late examples of neobaptistos, as confirmed by the twenty-first-century Thesaurus linguae graecae. As for the sites of initiation, so too for the rituals’ participants: Greek words for light outshone words for water.

Before proceeding to individual examples of phōtistēria, another well-attested Greek term for a site of initiation in early Christian materials should be noted: kolumbēthra, an ancient Greek word for ‘pool’, a place for swimming or wading. For Christians, the word echoed the popular story of the healing of the paralytic, as narrated in John v.2–9: in that version the healing took place near a ‘pool’ by the ‘Sheep [gate]’, and thus the word kolumbēthra retained an association with baptism, healing and the salvation experienced by the paralytic.Footnote 12 In addition to many early Christian homilies about this story, an ancient papyrus records a prayer to the ‘God of the Sheep Pool’, and another papyrus receipt from an Egyptian monastery mentions a mechanism that draws water from a garden to fill up their kolumbēthra.Footnote 13 Inscriptions also use the term to refer to the basin that holds water for baptism, although it does not seem to refer to the room or the overall building, in the way that baptistērion or phōtistērion might.Footnote 14 Early Christian Latin, especially in the fourth century and later, also uses some words for ‘pond’ or ‘pool’: piscina (fish pond) was a popular term for the site of baptism, along with natatorium (swimming pool) and fons (spring of water).Footnote 15 The present study focuses on the Greek evidence, though, due to the distinctive use of the word phōtistērion.

Five epigraphic examples of the word phōtistērion are especially clear and can serve as a representative data set, along with a sixth that is suggestive:

1. Bsakla (northwest Syria). The earliest extant example comes from Bsakla/Beseqla in Syria and has not been officially published. Prior to the current civil war in Syria the mosaic inscription was preserved in the mosaic museum at Maarat al-Numan where it was photographed in 2010 (see fig. 1).Footnote 16 Dated provisionally to 404 ce in connection to a dated inscription presumably from the same church, it reads: ‘Having made vows to saints, Marianos, son of Theodosios, [provided for] laying the mosaics of the basilica of the holy phōtistērion, by the zeal of Mesika the most-revered presbyter and Martinos the deacon.’Footnote 17 The location is not far from the professionally excavated site of Huarte, which also has an inscription for a phōtistērion.Footnote 18

Figure 1. Dedicatory inscription for phōtistērion in Bsakla / Beseqla, Syria (5th century ce). Open access. Photo by Sean Leatherbury/Manar al-Athar, image ID 28489, Manar Al-Athar archive, <http://www.manar-al-athar.ox.ac.uk>.

2. ‘Evron (Galilee). This example is dated to 442/3 by connection to another inscription in the same church. It is the one that caused Avi-Yonah to wonder why it was in a different room from the basin for water baptism. Found on a church floor near the town of Nahariya, it reads simply: ‘In the time of the most-revered presbyter Marinos, the phōtistērion was renovated.’Footnote 19 Apparently no photograph exists of this inscription, which was uncovered during the settling of a kibbutz on the property. The Israel Antiquities Authority could not locate a photograph in its archives nor could the overseer of the site's modest archaeological museum, when consulted in 2017.Footnote 20 The kibbutz chose to backfill most of the excavated church floor and let vegetation cover it again, keeping the area clear of modern buildings but not uncovered for viewing. Other inscriptions from the church record votive memorials of donors. This particular inscription is north of the sanctuary and directly east of the room that houses the basin for baptism.

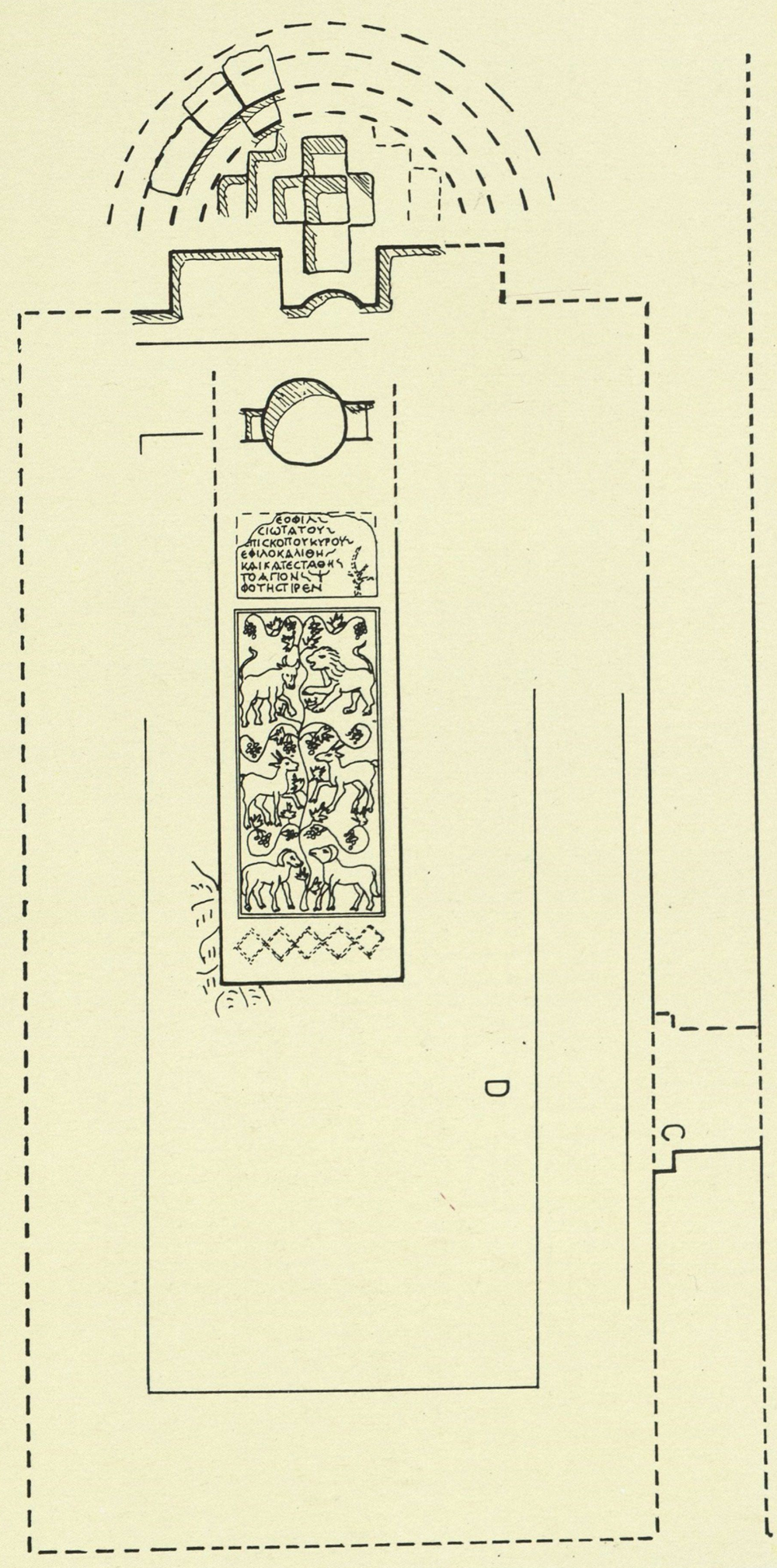

3. Madaba (Jordan). Two archaeological layers of a ‘baptistery chapel’ were excavated in Madaba: a newer upper layer with a cruciform water basin and a lower older layer, dated to the early sixth century, with a circular water basin (see fig. 2).Footnote 21 A well-preserved mosaic was discovered in the older layer: six animals face each other on two sides of a vine that grows toward the basin, and an almost fully preserved inscription sits immediately in front of the basin: ‘In the time of the most God-beloved and most holy bishop Cyrus, the holy phōtistērion was repaired and established.’Footnote 22

Figure 2. Line drawing of lower layer of ‘lower baptistry chapel’ at Madaba, Jordan (6th century ce), from Piccirillo, Mosaics of Jordan, fig. 123. Reproduced by permission of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, Mt Nebo, and the American Center of Oriental Research, Amman.

4. Kursi/Gergesa (Galilee). During the excavation of a Byzantine church in eastern Galilee, a complete mosaic inscription signals the entrance to a phōtistērion: ‘In the time of the most God-beloved presbyter and leader Stephanos, the mosaic of the phōtistērion was made, in the month of December, the fourth indiction, during the first consulship of our pious and Christ-loving emperor Maurikios’ (583–4 ce).Footnote 23 The initial publication of this inscription correctly resists translating the word as ‘baptistery’, but incorrectly states that the term is ‘not very frequent to designate a baptistery’.Footnote 24 None the less, the author plausibly speculates that rooms called diakonikon and phōtistērion are ‘important annexes of a church that might contain the baptistery’, thus endorsing the possibility that phōtistērion could be a designation of a larger annex for initiation rites within which the baptistery was one part.Footnote 25

5. Mount Nebo (Jordan). Like the example from Madaba, another from nearby preserves an inscription immediately to the left of a four-lobed water basin (see fig. 3). Discovered at Mount Nebo in what is called the ‘new baptistery chapel’, the mosaic medallion reads: ‘With the aid of our Lord Jesus Christ, the work of the holy sanctuary with the phōtistērion was completed.’Footnote 26 It is dated to 597 ce by a second medallion inscription on the other side of the basin. With the absence of other dedicatory inscriptions, the term phōtistērion seems to denote the entire room in which the water basin sits, and thus coheres with the probable interpretations of the previous two examples.

To these five examples, a sixth might be added, though tentatively. The city of Kourion in Cyprus underwent a major professional excavation that revealed a significant church from approximately the sixth century.Footnote 27 It had several adjoining rooms for the rites of initiation, the largest of which is labelled in the archaeological report as ‘baptistery’, next to two smaller rooms labelled ‘apodyterion’ (a room for getting undressed) and ‘chrismarion’ (a room for anointing). The basin for water baptism was in between the two smaller rooms, and not properly in the large room, which the archaeologists label ‘baptistery’. The mosaic of interest lies at the threshold to this largest room, suggesting that its contents signify a primary meaning of the annex overall. This mosaic, which greets candidates for initiation as they enter the multi-room annex, is a quotation from a Psalm: ‘Come forward to him, and be illuminated, and your faces shall surely not be ashamed’ (LXX Psalm xxxiii. 6).Footnote 28 This quotation is elsewhere associated with initiation in homilies and hymns.Footnote 29 The candidates are invited to cross the threshold, to ‘come forward’ (προσέλθατε), in order to ‘be illuminated’ (ϕωτίσθητε), which suggests that their construal of the overall multi-room complex and the overall signification of the composite set of rituals was related more to light and illumination than it was to water. In other words, despite the archaeologists’ label, this was probably described by its ancient initiates as a phōtistērion.

Figure 3. Photograph of phōtistērion at Mt Nebo, Jordan (6th century ce), from Piccirillo, Mosaics of Jordan, fig. 197. Reproduced by permission of the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, Mt Nebo, and the American Center of Oriental Research, Amman.

Why not baptistērion?

So why not baptistērion? Why was it used infrequently? One possibility is that the fragmentary nature of the evidence is misleading. Most of the Greek inscriptions dedicating sites of initiation from this era come from Galilee, Syria and Jordan, offering an incomplete picture of Greek-speaking early Christians. Perhaps the word baptistērion was indeed used in Greek-speaking congregations further west and the evidence hides that fact. However, if that were the case, one would expect a more significant linguistic footprint for the word in Greek literature, which there is not.

Another possibility for the absence of the word baptistērion relates to the practical reality of the rituals occurring in the room. That is to say, the vast majority of these rooms – these phōtistēria – do not have basins large enough in which to ‘baptise’ in the literal sense of the word. These basins were not big enough for anyone but a small child to be dunked, to be fully submerged in water. It is most likely that initiates in these rooms were being ‘baptised’ not literally by immersion, but rather with affusion, the pouring of water over the head and body. That is to say, the fact that Christian initiates were not going under water perhaps led to their not calling the room that housed the ritual ‘the place where you are immersed under water’.

A third possibility – and none of these possibilities are mutually exclusive – is that the conceptual metaphor of ‘illumination’ captured more of what these Christians thought the rites of initiation performed. That is to say, even if phōtistērion might not denote a different ritual space from baptistērion, historians can still be more attentive to what the designation evokes. In the categories of the philosopher of language Gottlob Frege, even in cases when the physical referent (Bedeutung) of two words or phrases may be the same, the sense (Sinn) of those words or phrases can differ. Historians of Christianity intuitively grasp the different things that a word might ‘mean’ in other ritual contexts: any given Sunday, one Christian denomination might ‘kneel’ before an ‘altar’, while another ‘gathers’ at a ‘table’. Both ‘altar’ and ‘table’ refer to a flat surface with four legs upon which consecrated bread is laid, but the senses evoked by the terms are, for one, a place for priestly sacrifice and, for the other, a place for a familial meal. In a similar way, either being ‘dunked’ or being ‘illuminated’ evokes different ways of construing the composite, overall meaning of the set of rituals of initiation.

Focal points of interpretation

It is no surprise that the image of light was a master metaphor for initiation. Light is the most widespread metaphor in the world's religions and, for Jews and Christians, the very origin of God's activity in the world.Footnote 30 As the magisterial church historian Jaroslav Pelikan showed in his book, The light of the world, much of early Christian theology and soteriology can be understood by its interactions with the imagery of light.Footnote 31

These facts notwithstanding, what specifically about the initiation rituals might have encouraged certain Christians to use ‘light’ imagery more than ‘water’ imagery? While no singular cause can be identified, there are a few focal points that show how eastern Christians in late antiquity imagined initiation as illumination. These spring from the scholarly consensus that ‘the theme of divine light is more prominent in the East than in the Latin West’; and that the Western approach to imagery of light is ‘mainly epistemological’, while the Eastern is also ‘experiential’.Footnote 32 The epistemological approach in both West and East accounts for widespread use of light to mean knowledge and even catechesis. This goes back to Paul's letters, where 2 Corinthians iv.4–6 refers to the phōtismos of the Gospel and of knowledge (gnōsis). Justin Martyr makes clear the equation of baptismal initiation and illumination by means of the connection between illumination and knowledge: ‘Illumination is the name given to this washing since those being taught these things are illuminated in their minds.’Footnote 33 Beyond these epistemological meanings, eastern narrations of illumination ‘often denote a specific spiritual experience, undergone not only inwardly but sometimes also outwardly in the body’.Footnote 34

The first point of interpretation is the ever-present relationship between oil, fire and light during Christian initiation. Whether encased in an earthenware lamp or poured on the tip of a torch, oil was, apart from the sun, the ancient world's primary source of light. The Acts of Thomas offers particularly rich evidence of how initiation was understood and perhaps practised in early Syrian Christianity, narrating five instances of conversion and initiation. The first and longest of these, the initiation of King Gundaphorus, is noteworthy in that it does not narrate water baptism at all, but only rites of anointing, illumination and eucharist:Footnote 35

[The Apostle] ordered [the initiates] to bring him oil, so that through the oil they might receive the seal. So they brought the oil and they lighted many lamps, for it was night. The Apostle stood up and sealed them [in the following manner]: The Lord was revealed to them through a voice saying, ‘Peace to you, brethren.’ They only heard the voice, and did not see his form, for they had not yet received the sealing of the seal. The Apostle took the oil, poured it over their heads, smeared it, anointed them, and then said [a series of invocations] … When they had been sealed, a youth appeared to them carrying a lighted torch, so that even the lamps became faint by the approach of its light. He exited and became invisible to them. The Apostle said to the Lord, ‘Lord, your light is incomprehensible to us, and we cannot bear it, for it's too great for our vision.’ When the (sun)light appeared and day dawned, he broke bread and made them partakers of the eucharist of Christ.Footnote 36

This ritual narrative focalises the reader's attention on light and the anointing oil, which is the subject of prayers (‘epicleses’) and which enables a period of sacramental vision. Only after being ‘sealed’ with the oil can a recipient see the presence of the Lord, who in this case appears as a youth carrying a blazing torch. And though our modern sensibilities, subconsciously formed by the ubiquity of electricity, might fail to appreciate the symbolism at first, this narrative and others make plain the connection between oil/anointing and light/illumination. Anointed with oil, surrounded by oil lamps, the initiates come to see the Lord, who outshines their lamps with a blazing torch, fuelled also by oil. Susan Myers concludes that, for all the initiation scenes narrated in the Acts of Thomas, ‘water baptism is, of the initiatory practices, third in value’, after anointing and eucharist.Footnote 37 Therefore, a Christian community that emphasised anointing in addition to (or more than) baptism might reasonably be led to call its initiation room a phōtistērion.

Cyril of Jerusalem also describes how initiates called phōtizomenoi carried their torches in procession toward the rites of initiation, while the women in procession on the painted walls of the Dura-Europos house-church were shown doing the same.Footnote 38 Elsewhere in Syrian texts, the Syriac Acts of John twice describes a blazing fire over oil at its consecration, while Syrian and Maronite liturgical texts depict a ‘flaming baptismal font’; Jacob of Serugh and Romanos the Melodist embrace the paradox, calling the water of baptism a ‘furnace’.Footnote 39 These references make even more sense when one notes a second focal point of interpretation: the early Christian recollection of the light at Jesus’ own baptism.

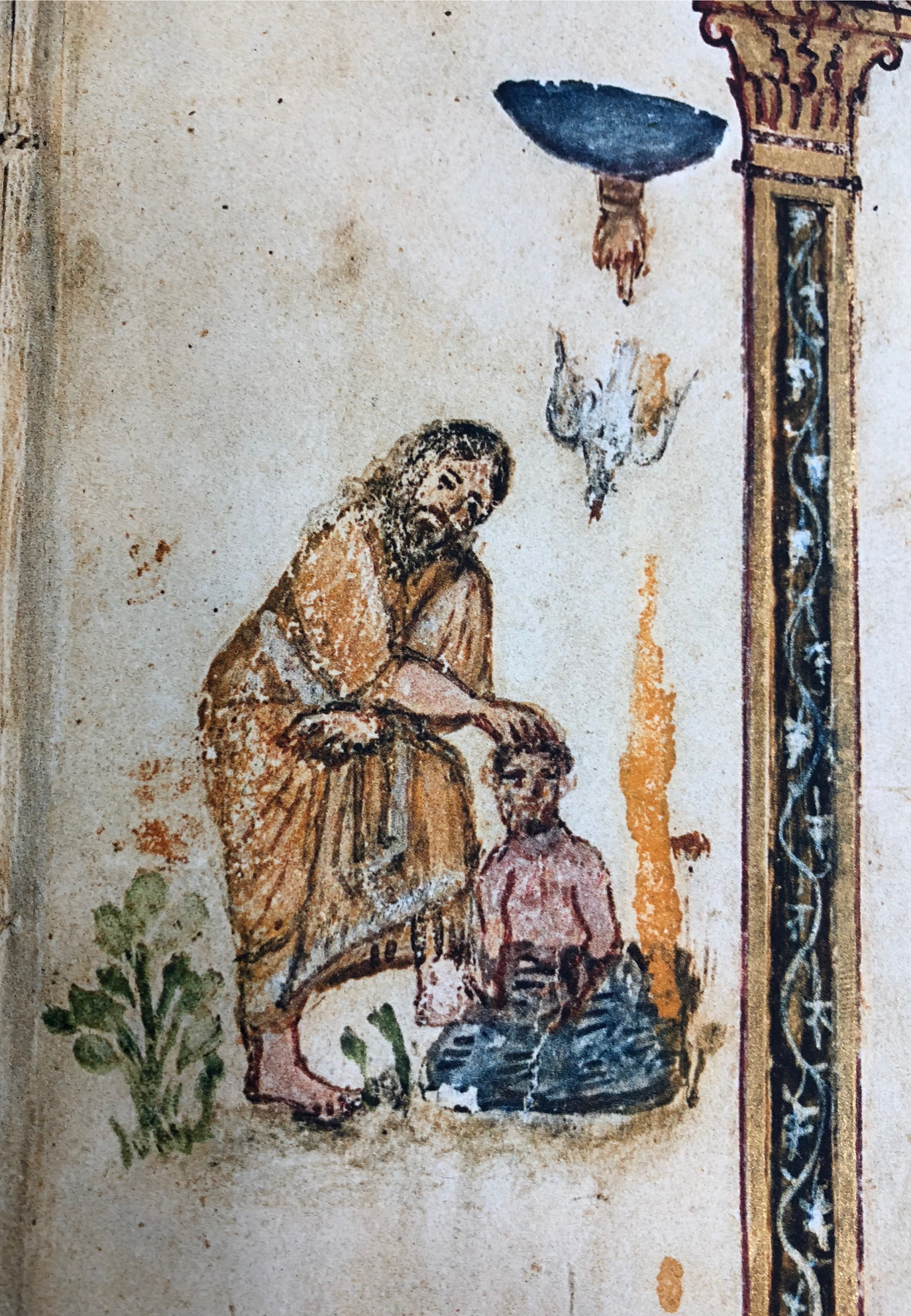

Though the canonical Gospels do not narrate such illumination, describing only the divine voice and the dove as signs of God's activity, the presence of fire and/or light was attested as early as Justin Martyr: ‘As Jesus went down into the water, the Jordan was set ablaze.’Footnote 40 It appears in other sources too, such as Old Latin versions of Matthew's Gospel: ‘when he was baptised, a flaming light shone around the water’.Footnote 41 Most important for our purposes, early Syrian texts and art (the Rabbula Gospels, see fig. 4) transmit this tradition of light at Jesus’ baptism, which has been traced in detail by Gabriele Winkler. Her argument is crucial because ‘for the Syrians, the Jordan event forms the model for the shape of their baptismal rites’.Footnote 42 The baptismal order of the Maronites, which Winkler considers to have retained ‘the oldest Syrian baptismal theology’, is replete with imagery of light and illumination, its invoked prayers flickering back-and-forth between the one-time Jordan event and the baptismal font of later centuries.Footnote 43 ‘The appearance of a light at the baptism of Jesus’ had the ‘widest dissemination’ and citations from liturgical texts ‘could be continued indefinitely’, from early Jewish-Christian Gospels (e.g. the Gospel of the Ebionites) to the Diatessaron, Ephrem, Jacob of Serugh and beyond.Footnote 44 As early as the fourth century the feast of Epiphany – celebrating, in part, Jesus’ baptism – was being described by the name ‘ta phōta’ (‘The Lights’).Footnote 45

Figure 4. Close-up of miniature of Jesus’ baptism, with fire upon the water: canon table, Rabbula Gospels (586 ce), Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, Plut. 1.56, fo. 4v. Public domain, <http://teca.bmlonline.it/ImageViewer/servlet/ImageViewer?idr=TECA0000025956&keyworks=Plut.01.56>.

Many texts are suggestive of fire at initiation, and some even discuss the appearance of a mystical or heavenly light, a kind of anamnēsis, a ritual recollection and reenactment of the light at Jesus’ own baptism. For example, consider an unusual and little-known Coptic letter from Theophilus of Alexandria to the Pachomian monk Horsiesios.Footnote 46 The archbishop asks the monk to come to the city to help him out with the baptismal ritual, since he is having trouble consecrating the water. ‘Since my fathers they have come to baptise on the appropriate day, and while they are praying by the pool, a ray of light (oy-rhabdos n-oyoein) comes and seals the waters. But this year we have not been worthy to see this.’Footnote 47 He then goes on to say he had a vision that Horsiesios can help him. Horsiesios does indeed come, and he deflects praise by contrasting the small light of a lamp (himself) to the light of the sun (Christ), drawing on the aforementioned imagery in the Acts of Thomas, Methodius and elsewhere.Footnote 48

With the monk's help, the shaft of light does then appear. The entire episode is couched as an etiological tale about the proper date of Easter initiations and probably also serves to comment on the relationship between institutional (archbishop) and charismatic (monk) authorities. Perhaps the pillar of fire at the Exodus was the connection that they drew to Easter. It is true that the letter does not call the room a phōtistērion, instead using both the Coptic word for ‘bridal chamber’ (sheleet) and the Greek loan-word baptistērion, while the basin for water is a kolumbēthra.Footnote 49 Yet it remains another vivid example of the experiential centrality of light in the narration of early Christian initiatory rituals – even when water seems to be the context of discussion.

Theophilus of Alexandria was distraught because he had ‘not been worthy to see’ the sign of light at baptismal initiation. This suggests a third focal point of interpretation: an ideal of sacramental vision, a connection between initiation and a new kind of visuality, which was emphasised by sources from Syria, Egypt and Cappadocia – and was already seen above through the Acts of Thomas.Footnote 50 Beyond the biblical resonances of these ritual descriptions, they may also draw on the traditional mysteries, such as those of Isis, which used darkness-to-light rituals at their culminating encounters with a god or goddess. Basil of Caesarea, for his part, makes explicit the new spiritual visuality enabled by Christian initiation: ‘Ignorance of God is death to the soul. The unbaptised person is not illuminated. Lacking illumination, the eye cannot function; the soul cannot contemplate God.’Footnote 51 Basil likely draws on the extramission theory of vision, the widespread (albeit variously defined) ancient notion that eyes sent something out to enable perception. Just as an internal biological fiery light enables natural vision, so does a divine light kindled at one's initiation enable a new form of sacramental vision. These connections are solidified in the words of Pseudo-Dionysius:

The same is no less true for the holy sacrament that produces God's birth within us, since God is the Creator of light and the basis of all divine illumination, and so it is correct for us to praise this sacrament according to its proper functioning under the name of illumination. Although all hierarchic actions transmit light to the faithful, it is indeed this sacrament which first opens our eyes, its original light allowing us to view the light diffused by the other sacraments.Footnote 52

If a new sacramental vision is the paramount effect of Christian initiation, that which enables all other sacramental activities to be viewed, then the primal sacrament is properly called ‘illumination’.

These early Christian sacramental theologians drew on biblical models that united water and vision, as when Ephrem describes Jesus’ healing of the man born blind at the pool of Siloam (John ix): in Ephrem's interpretation, that man's eyes were ‘illuminated’ by the water.Footnote 53 The inauguration of a new light which empowers is akin to Methodius of Olympus' explanation of why newly initiated Christians are called neophōtistoi. He compares the uninitiated to the moon, which does not generate light of its own; but those who are regenerated are able to shine with a new ray of light, as reflections of Christ, the sun, and ‘thus are periphrastically called newly illuminated’ (neophōtistoi).Footnote 54

These three aspects of interpretation lead to the conclusion that Christians who used the word phōtistērion for their sites of initiation probably understood initiation to be a composite rite, a set of rituals which involved the embodied fire of oil, the recollection of Jesus’ baptism with water and fire, and the illumination of the mind and soul, all of which led to experienced effects of sacramental vision. As historians of initiation have charted in detail, baptism by immersion or affusion was only part of the composite experience of initiates in late antiquity, which also could include enrollment, catechesis, fasting, anointing, exorcism, exsufflation, renunciation, professions, undressing and dressing, chrismation, eucharist and more. Some modern historians, such as Juliette Day, Everett Ferguson and Bryan Spinks, have used ‘baptism’ as a synecdoche for the whole set, even while richly describing the components of the experience; Hugh Riley and Maxwell Johnson prefer ‘initiation’ as the representative term, which leaves room for those traditions that emphasise anointing or eucharist in the process.Footnote 55 And though liturgical texts and ‘church orders’ from the fourth through sixth centuries do not use the word phōtistērion (as the extant inscriptions do), their textual descriptions of the initiates favour the light metaphor. The relevant writings of Cyril of Jerusalem, Gregory of Nazianzus, Ephrem, Romanos and others support the liturgical designation of neophōtistoi, the term found also in church orders, such as the fourth-century Apostolic constitutions and the fifth-century Testamentum Domini.Footnote 56 By focusing on illumination as the overarching image for initiation, the authors of such texts were not innovating but in fact drawing on biblical precursors, such as the book of Hebrews (vi.4; x.32), and adapting them to their developing sacramental theologies. In sum, the evidence shows that significant numbers of Christians in late antiquity chose ‘illumination’ as the image by which to express the composite rite and ‘phōtistērion’ as the name for its site.

A penitent enters her phōtistērion

This article has drawn from epigraphic and literary sources to argue that phōtistēria were at least as widespread as baptistēria among Greek-speaking early Christians, and probably more so. While it is difficult to determine precisely the significance of this designation, the safest judgement is that the Christians who built and used phōtistēria imagined ‘illumination’ to express the composite rite of initiation, within which ‘baptism’ was only one part. By way of conclusion, consider one of the only surviving literary texts to give contextual clues to the liturgical meaning of phōtistērion: a hymn (kontakion) of Romanos the Melodist, the liturgical composer who was born in the same time and region of most of our extant phōtistēria (born late fifth century in Syria and died mid-sixth century in Constantinople). His hymn in the voice of the repentant sinner of Luke vii.36–50, the woman who anoints Jesus’ feet and is forgiven by him in the house of Simon the Pharisee, recapitulates several points of this article in one poetic stanza. Using the ancient rhetorical technique of speech-in-character, Romanos imagines these words on the lips of the penitent woman:

What is most striking about this use of phōtistērion is its juxtaposition with so many words that relate to washing and cleansing with water.Footnote 58 The woman will ‘scrub off’ (ἀποπλύνομαι), ‘purify’ (‘καθαρίζομαι’), ‘bathe’ (‘λούομαι’), ‘wipe clean’ (‘σμήχομαι’), and ‘escape from filth’ (‘ἐκϕεύγω τοῦ βορβόρου’) in the ‘kolumbēthra’ that she will prepare – and yet Romanos does not use the word baptistērion to describe the imagined site in which the basin of water and all this explicit washing occurs. The modern English edition of Romanos's kontakia obscures this fact, rendering phōtistērion once again as ‘baptistery’.Footnote 59

Romanos, being a native of the region where Syria meets Lebanon, a region containing dedicatory inscriptions that avoid the word baptistērion, instead chose kolumbēthra to describe the water basin and phōtistērion to describe the room that houses the composite rite. Just as a contemporaneous initiate at Kourion would cross a physical threshold by walking over a mosaic about illumination, so here does the penitent cross the imagined threshold of the Pharisee's house accompanied by the same Psalm. When he describes her initiation, Romanos draws on his understanding of what occurred at Jesus’ own baptism: both of his hymns on Epiphany depict a fiery light at the Jordan.Footnote 60 Here she approaches the sun, where her past deeds will be exposed and yet she will not feel ashamed in that light. Like the moon coming out of its phase of darkness, she will receive illumination from the source of all light. In this house she will use oil and water, to be sure, but her composite process of initiation is framed as one from darkness to light – to be illuminated in a phōtistērion.