Impact Statement

We provide a review and prospectus on the future of coastal monitoring using imagery from Earth-observing satellite and advanced machine-learning and data-assimilation techniques.

Introduction

The coastal zone is the interface between oceanic, terrestrial, and anthropogenic forces. Sandy coasts, in particular, are increasingly encroached upon by urban development on the landward side, while waves, storms, and sea-level rise encroach upon their seaward side. This so-called “coastal squeeze” (Doody, Reference Doody2013; Pontee, Reference Pontee2013) is becoming increasingly apparent and problematic and may lead to permanent loss/drowning of beaches as sea-level accelerates and landward beach migration is restricted (Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard and Limber2017b; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Masselink, Masselink, Coco, Short, Castelle, Rogers and Jackson2020), eliminating the recreational, economic, ecologic, and flood-protection services beaches provide (Barbier et al., Reference Barbier, Hacker, Kennedy, Koch, Stier and Silliman2011; Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Dugan, Page, Wood, Hart, Cayan, Erikson, Hubbard, Myers, Melack and Iacobellis2021). Prior to coastal armoring, sandy beaches were resilient landscapes, which maintained their existence by migrating according to the forces that moved them (FitzGerald et al., Reference FitzGerald, Fenster, Argow and Buynevich2008; Cooper et al., Reference Cooper, Masselink, Masselink, Coco, Short, Castelle, Rogers and Jackson2020). Beaches evolve at a variety of time scales, from seconds to centuries (e.g., episodically and chronically), in response to tides, waves, sea-level rise, fluvial sediment inputs, and a multitude of other site-specific processes (Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Limber, Erikson and Cole2017c). In certain cases, the erosion and recovery of beaches due to waves and storms is predictable: state-of-the-art erosion models (and ensembles thereof) can often demonstrate considerable skill in blind tests (Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Antolínez, Beuzen, Bryan, Cagigal, Castelle, Davidson, Goldstein, Ibaceta, Idier, Ludka, Masoud-Ansari, Mendez, Brad Murray, Plant, Ratlif, Robinet, Rueda, Sénéchal, Simmons, Splinter, Stephens, Townend, Vitousek and Vos2020). In other cases, in complex environments and for exceptional storms, the erosion response often remains unpredictable or highly uncertain (Murray, Reference Murray2007). In either case, coastal monitoring data are critical to either train or supersede models. Unfortunately, observations of coastal change with high spatiotemporal resolution only exist at a small number of well-monitored sites (e.g., Morton et al., Reference Morton, Leach, Paine and Cardoza1993; Birkemeier et al., Reference Birkemeier, Nicholls, Lee, Kraus and McDougal1999; Ruggiero et al., Reference Ruggiero, Kaminsky, Gelfenbaum and Voigt2005; Kuriyama et al., Reference Kuriyama, Ito and Yanagishima2008; Hansen and Barnard, Reference Hansen and Barnard2010; Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Hubbard and Dugan2012; Ludka et al., Reference Ludka, Gallien, Crosby and Guza2016; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harley, Short, Simmons, Bracs, Phillips and Splinter2016b; Splinter et al., Reference Splinter, Harley and Turner2018). Present-day remote-sensing techniques (e.g., Lidar from aircraft) have significantly increased the spatial extent of coastal monitoring efforts, albeit with limited frequency (e.g., semi-annual at best). Imagery from Earth-observing satellites in combination with machine-learning models promises to transform coastal science from a “data-poor” field, where data are spatiotemporally sparse, into a “data-rich” field, where new observations are collected daily for the entire world. Satellites have already been used to generate coastal observations across national and global scales (Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018). This paper presents a review and prospectus on the future of coastal monitoring through the lens of satellite remote sensing, with an emphasis on studying sandy beaches with optical imagery.

The future of satellite-based coastal monitoring shows great potential. Satellite-based monitoring systems will eventually deliver operational, global-scale, high-resolution, subdaily observations with meter-scale accuracy. Additionally, future coastal monitoring systems will be integrated with operational atmosphere-ocean-wave forecast models to produce data-assimilated predictions of coastal change, much like modern-day weather reports. Advances in satellite-based monitoring in combination with machine learning and data-assimilated modeling will be crucial to address lingering questions and debates about the causes and effects of coastal erosion over large scales. These high-resolution imagery and data from future coastal monitoring systems will likely reveal how pervasive the “coastal squeeze” has become in many locations, particularly in urban areas (Griggs and Patsch, Reference Griggs and Patsch2019). Satellites will allow us to watch, in high definition, the slow loss of many beaches and islands worldwide (e.g., Baker et al., Reference Baker, Harting, Johanos, London, Barbieri and Littnan2020) as global temperature and sea level rise (Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Dugan, Page, Wood, Hart, Cayan, Erikson, Hubbard, Myers, Melack and Iacobellis2021; Armstrong McKay et al., Reference Armstrong McKay, Staal, Abrams, Winkelmann, Sakschewski, Loriani, Fetzer, Cornell, Rockström and Lenton2022). Future coastal monitoring will also likely reveal the extent to which anthropogenic interventions like beach nourishments are necessary to sustain the existence of many beaches against sea-level rise.

In this paper, we focus on the future of satellite-based coastal monitoring systems designed to observe dynamic shoreline positions of sandy coasts (although many of the satellite platforms and methods detailed here may translate to monitoring in more diverse coastal environments). The comprehensive coastal monitoring systems of the future will likely comprise numerous components, for example, satellite-derived bathymetry, video-from-space, satellite-based structure-from-motion, remote sensing with active sensors like Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites, and monitoring of coastal cliffs, inlets, estuaries, wetlands, and habitats. However, many of these components (some of which are covered in other reviews; for example, Bergsma et al., Reference Bergsma, Almar, Rolland, Binet, Brodie and Bak2021; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harley, Almar and Bergsma2021) are not explored in detail in the current prospectus. Here, we primarily focus on satellite-derived shorelines as the most important and immediate priority of future coastal monitoring for a number of reasons: (1) sandy beaches generally front and provide protection for the most densely populated coastal landscapes and thus are often critical to preventing loss of life and property, (2) beach and waterline position can be observed directly from satellite imagery (and require very little inference, in contrast to underwater features), (3) satellite-derived shorelines represent the closest proxy to most long-term, in situ observations with high temporal resolution, which thus facilitates comparison among datasets, with shorelines being an excellent proxy for beach profile and volume change (Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Allan, Hansen, Kaminsky, Ruggiero and Doria2011), and (4) observations of shoreline positions (despite their many and varied definitions and applications; for example, Boak and Turner, Reference Boak and Turner2005; Pollard et al., Reference Pollard, Brooks and Spencer2019; Toure et al., Reference Toure, Diop, Kpalma and Maiga2019) can address many important, lingering scientific and management questions and challenges, such as chronic erosion rates, storm response and recovery, shoreline recession due to sea-level rise, lifespan of nourishments, and the connection between beach processes and fluvial/terrestrial processes.

We continue the prospectus (in section “Literature review”) with a brief review of past, present, and state-of-the-art/future coastal monitoring methods. Sections “Data-driven coastal science using machine learning” and “Integration with operational coastal-change models” highlight the critical roles that machine learning and data assimilation, respectively, will necessarily play in deriving relevant information and predictions from the raw data collected by future coastal-monitoring systems. Section “Challenges” discusses important technical and scientific challenges that must be addressed with future satellite-based coastal monitoring systems. Finally, section “Conclusions” concludes the prospectus.

Literature review

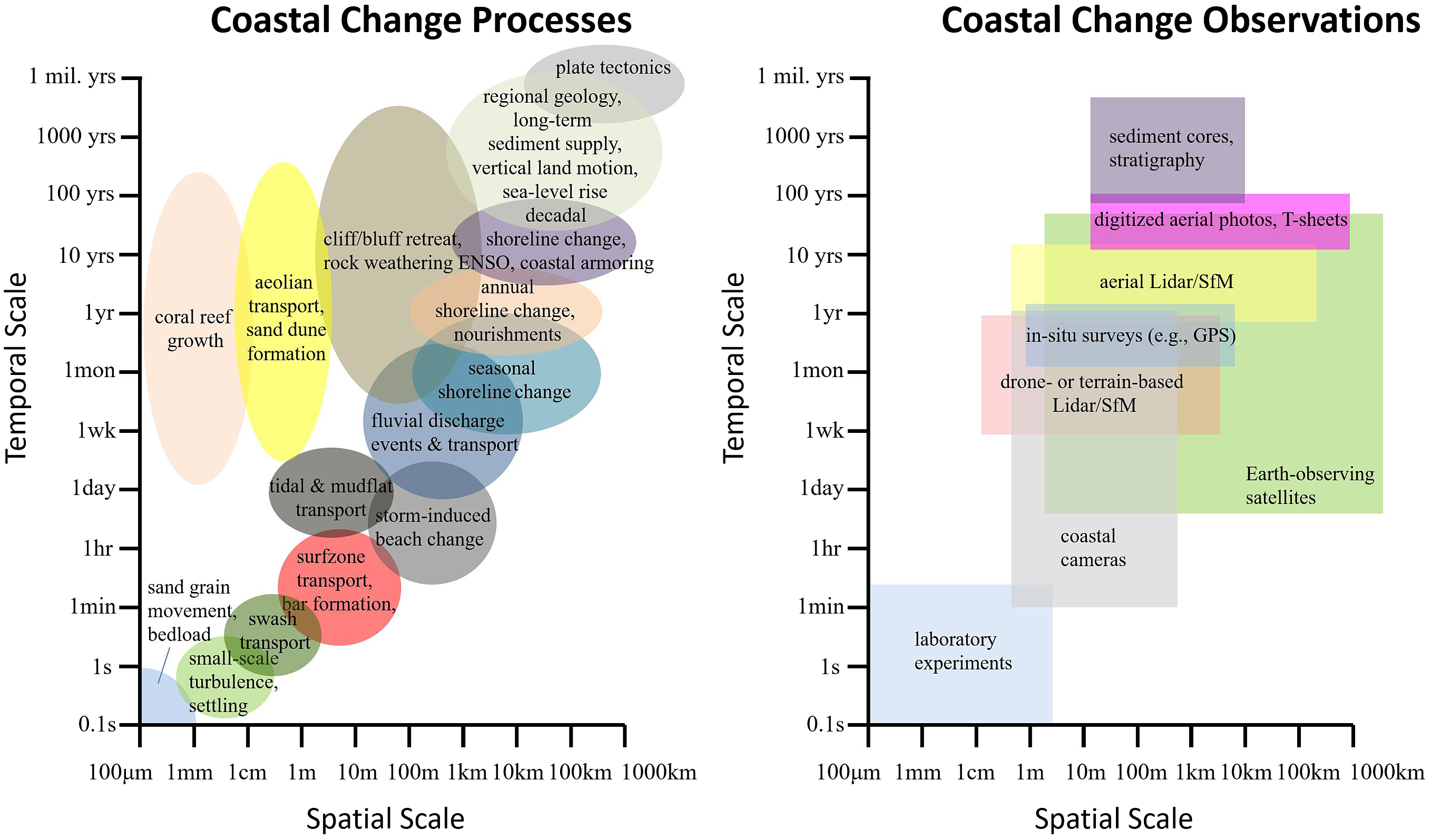

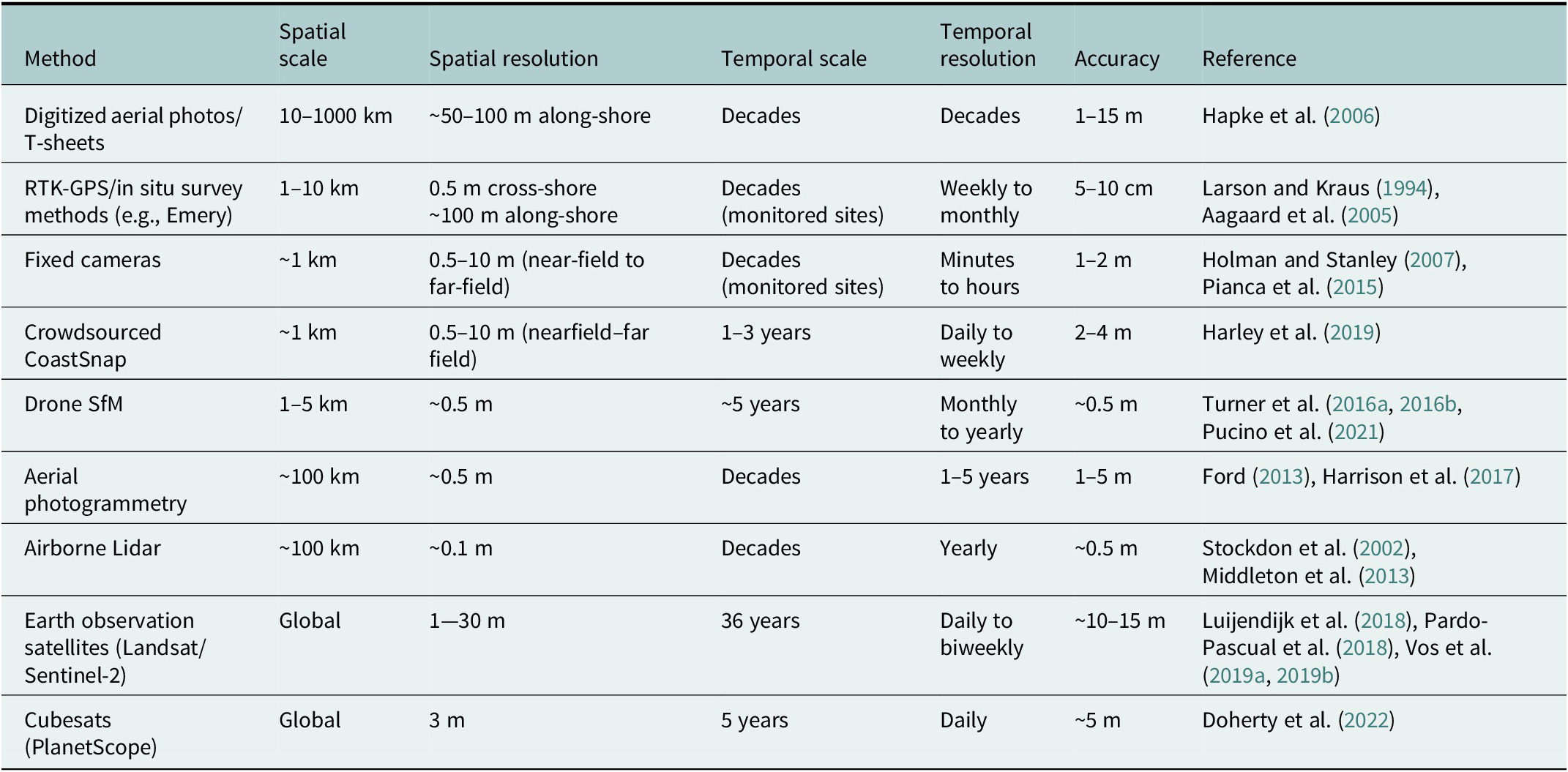

Many techniques exist to monitor beaches and beach processes, all with differing levels of accuracy, spatiotemporal resolution, and coverage, as depicted in Figure 1 and described in Table 1. Here, we briefly summarize the most popular past, present, and potential future monitoring methods and their influence on coastal science.

Figure 1. The multiscale nature of coastal-change processes (left) and observational techniques (right) that seek to capture behavior across scales. The coastal-change processes given here are adapted from Vitousek et al. (2017).

Table 1. Summary of the different modern technologies for shoreline monitoring

Coastal monitoring: Past

Long-term observations of coastal change only exist at a handful of well-monitored beaches, for example, Duck, North Carolina (Larson and Kraus, Reference Larson and Kraus1994), Torrey Pines, California (Ludka et al., Reference Ludka, Guza, O’Reilly, Merrifield, Flick, Bak, Hesser, Bucciarelli, Olfe, Woodward, Boyd, Smith, Okihiro, Grenzeback, Parry and Boyd2019), Ocean Beach, California (Hansen and Barnard, Reference Hansen and Barnard2010; Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Hubbard and Dugan2012), the Columbia River littoral cell in Oregon and Washington (Ruggiero et al., Reference Ruggiero, Kaminsky, Gelfenbaum and Voigt2005), and Fire Island, New York (Lentz and Hapke, Reference Lentz and Hapke2011), in the U.S.; Ensenada, Mexico (de Alegría-Arzaburu et al., Reference de Alegría-Arzaburu, Gasalla-López and Benavente2022); Narrabeen-Collaroy, Australia (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harley and Drummond2016a, Reference Turner, Harley, Short, Simmons, Bracs, Phillips and Splinter2016b); Hasaki, Japan (Kuriyama et al., Reference Kuriyama, Ito and Yanagishima2008; Banno et al., Reference Banno, Nakamura, Kosako, Nakagawa, Yanagishima and Kuriyama2020); Truc Vert, France (Castelle et al., Reference Castelle, Bujan, Marieu and Ferreira2020); Portrush, Perranporth, and Slapton Sands in the U.K. (Masselink et al., Reference Masselink, Castelle, Scott, Dodet, Suanez, Jackson and Floc’h2016); South Holland, Netherlands (de Schipper et al., Reference de Schipper, de Vries, Ruessink, de Zeeuw, Rutten, van Gelder-Maas and Stive2016). Large-scale (>100–1,000 km) “snapshots” of historical coastline state exist, typically in the form of so-called “shorelines,” which have varying definitions and are digitized from various sources, for example, “T-sheets” and aerial photos (Shalowitz, Reference Shalowitz1964; Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, Hayden, May and May1980; Anders and Byrnes, Reference Anders and Byrnes1991; Crowell et al., Reference Crowell, Leatherman and Buckley1991; Hapke and Richmond, Reference Hapke and Richmond2000; Fletcher et al., Reference Fletcher, Rooney, Barbee, Lim and Richmond2003; Boak and Turner, Reference Boak and Turner2005). Seamless, large-scale assessments of coastal change, for example, the USGS National Assessment of Shoreline Change (Hapke et al., Reference Hapke, Reid, Richmond, Ruggiero and List2006), have often relied on fitting trend lines to small numbers (i.e., 4–10, at best) of historical shorelines, which often have decade-long gaps and are taken inconsistently at different seasons, wave conditions, tide phases, and so forth. Hence, older coastal-change studies can arguably be categorized as either (1) studies of a specific beach with high spatiotemporal resolution or (2) studies of a long coastline (e.g., >100–1,000 km) with temporally sparse data. Fortunately, newer technologies have increased the spatiotemporal resolution and extent of coastal observations and analyses (as described below).

Coastal monitoring: Present

Remotely sensed coastal observations in the form of topographic and bathymetric Lidar from airplanes became a boon for coastal science near the turn of the century (Sallenger et al., Reference Sallenger, Krabill, Swift, Brock, List, Holman, Manizade, Sontag, Meredith, Morgan, Yunkel, Frederick and Stockdon2003). For the first time, seamless digital elevation models (DEMs) were available for both coastal/shoreline-change detection (Stockdon et al., Reference Stockdon, Asbury H, List and Holman2002) and site-specific modeling applications. DEMs enhanced our view of the coast, enabling examination of three-dimensional (3-D) structure beyond traditional two-dimensional (vector-based) representations of the shoreline (e.g., elevation contours of coastal topography or proxies thereof). Although Lidar DEMs remain indispensable tools for coastal/hydrodynamic/flood modeling, they arguably have not had as great of an effect to proliferate data-driven studies of dynamic coastal change. Airborne Lidar data collection (and the observed coastal/shoreline state derived therein) remains annual or multiannual at best, due to their high cost and post-processing requirements. Some exceptional coastal-change studies have commissioned and used biannual Lidar surveys (cf. Yates et al., Reference Yates, Guza, O’Reilly and Seymour2009); however, most Lidar DEMs remain isolated “snapshots” of dynamic coastal landscapes. The size and complexity of 3-D Lidar point-cloud data, which must be post-processed into DEMs, are often rate-limiting factors for the frequency and availability of Lidar data. Even “rapid response” pre-and post-storm Lidar collection missions can take years to become fully processed and available.

Terrain-based Lidar (e.g., Young et al., Reference Young, Guza, Matsumoto, Merrifield, O’Reilly and Swirad2021) and drone-based Structure-from-Motion (SfM) (e.g., Turner et al., Reference Turner, Harley and Drummond2016a, Reference Turner, Harley, Short, Simmons, Bracs, Phillips and Splinter2016b) or drone-based Lidar (Troy et al., Reference Troy, Cheng, Lin and Habib2021) techniques were developed to overcome the temporal sparsity of aerial Lidar data. Despite the notable successes of terrain-based Lidar and drone-based SfM/Lidar for certain landscapes such as cliffs and dunes, the major limitation of these technologies is their narrow geographic scope. Aerial SfM techniques (such as the USGS Plane Cam) were developed as a cost-effective alternative to Lidar for collecting coastal-change data with high temporal resolution over large spatial scales (Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Warrick, East, Magirl, Stevens, Bountry, Randle, Curran, Hilldale, Duda, Gelfenbaum, Miller, Pess, Foley, McCoy and Ogston2018; Warrick et al., Reference Warrick, Ritchie, Schmidt, Reid and Logan2019). Yet, post-processing (e.g., to remove SfM artifacts caused by a moving waterline across a static beach) remains a rate-limiting factor for data availability.

Concurrently with (and often predating) the development of aerial Lidar/SfM, coastal camera technology emerged as a powerful tool for studying coastal processes and change (Holman and Stanley, Reference Holman and Stanley2007). “ARGUS”-type still and video cameras provide high-frequency, long-term (subseconds to interannual) imagery to observe and quantify beach/dune erosion (Palmsten and Holman, Reference Palmsten and Holman2012) and bathymetric state (Holman et al., Reference Holman, Plant and Holland2013) as well as hydrodynamic processes like waves (Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Carini, Harrison, Chickadel and Warrick2020), currents (Chickadel et al., Reference Chickadel, Holman and Freilich2003), and runup (Stockdon et al., Reference Stockdon, Holman, Howd and and Sallenger2006). Coastal cameras possess the desirable capability to observe and record synoptic hydrodynamic conditions and weather along with morphologic change (which is generally not possible with the other survey techniques mentioned above). However, coastal cameras (once again) remain narrow in their geographic scope (~1 km along-shore). Yet, crowdsourced camera platforms for monitoring coastal change like CoastSnap (Harley and Kinsela, Reference Harley and Kinsela2022) are rapidly expanding the scope of coastal monitoring.

The past-to-present-to-future progression of coastal monitoring systems (e.g., from the Emery (Reference Emery1961) survey method to survey rods/total stations to GPS to Lidar to cameras) is exemplified in Splinter et al. (Reference Splinter, Harley and Turner2018), “Remote sensing is changing our view of the coast,” which focuses on the highly monitored field site of Narrabeen-Collaroy, Australia. They concluded that, even though satellites represent the inevitable culmination of coastal monitoring over large spatial scales, a “complementary suite of remote sensing products” may always be needed.

Coastal monitoring: State-of-the-art and future

The publishing of Luijendijk et al.’s (Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018) “State of the world’s beaches” was a bellwether moment: it ushered in the “big-data” era of coastal science. Although several prior case studies investigated the identification of the shoreline from satellite imagery (as described below), Luijendijk et al.’s (Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018) study was truly the first application at scale. Using more than three decades of annual composites of Landsat imagery, they produced historical erosion rates on a global scale (see http://shorelinemonitor.deltares.nl/). Nevertheless, the study had limitations, for example, the misidentification of some rocky and hardscape coasts as sandy (which is practically impossible to avoid on a global scale, however) and the use of composite (time-averaged) images to average over tidal and seasonal fluctuations in shoreline/waterline position and cloud cover. Despite these limitations, Luijendijk et al.’s (Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018) research gives us a glimpse into the future, where satellites continuously monitor, update, and assess the state of the world’s beaches.

There are many unanswered questions surrounding the drivers, processes, and fate of coasts worldwide that can be addressed with prolific satellite observations. A fundamental challenge that pervades coastal science (among many other fields of Earth science) is multiscale behavior of coastal processes (Larson and Kraus, Reference Larson and Kraus1995; Hapke et al., Reference Hapke, Plant, Henderson, Schwab and Nelson2016; Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Chataigner, Yates, Le Dantec, Suanez, Cagigal, Floc’h and Townend2021), which is illustrated in Figure 1. As discussed above and as shown in Figure 1, individual coastal monitoring methods can generally capture only a limited range of spatiotemporal scales. Earth-observing satellites represent the future of coastal change monitoring for the simple reason that they can observe a far greater range of scales than any other method. Unlike all of the other traditional coastal monitoring techniques, satellites are the only method capable of observing coastal change with high-temporal frequency (e.g., daily to weekly) across very large spatial scales (e.g., global), which is a critical gap in Figure 1 that only satellites can fill. As discussed below in section “Scientific challenges,” having regular observations that can fill this critical gap enables us to address a number of lingering scientific questions about the processes and fate of coastlines over large scales.

Additionally, Earth-observing satellites have profoundly changed how we collect data. For the first time, we can look into the past to “collect” dataFootnote 1 (with regular intervals, high spatiotemporal resolution, and global coverage). This data-collection protocol fundamentally differs from traditional protocols, where field/laboratory campaigns must be thoroughly planned and meticulously conducted, often requiring 10s of hours of labor to capture a single shoreline for a discrete-time/location. Being able to regularly observe coastal change across four decades using the Landsat archive is the greatest advantage of this dataset. Thus, in spite of all the recent and planned improvements to satellite hardware and image resolution, the need to use software to better understand occurrences recorded in long-standing archives will never cease.

Optical satellites

In recent decades, a number of studies have used optical satellite imagery (including the infrared portions of the electromagnetic spectrum) to map changes in shoreline position with increasing levels of automation. While manual digitalization of shoreline position is a reliable and accurate method, particularly on high-resolution images (Ford, Reference Ford2013; Kelly and Gontz, Reference Kelly and Gontz2019), it remains time-consuming and impractical when employed for long stretches of coastline with hundreds of revisits. Instead, modern methods exploit the contrast in spectral signature between water and land to automatically identify the shoreline. In particular, water readily absorbs light in the near-infrared and short-wave infrared bands, but land does not. Hence, image indices, such as the normalized difference water index (NDWI, Gao, Reference Gao1996) and its derivatives, have become the cornerstones of remotely sensing divisions between water and land.

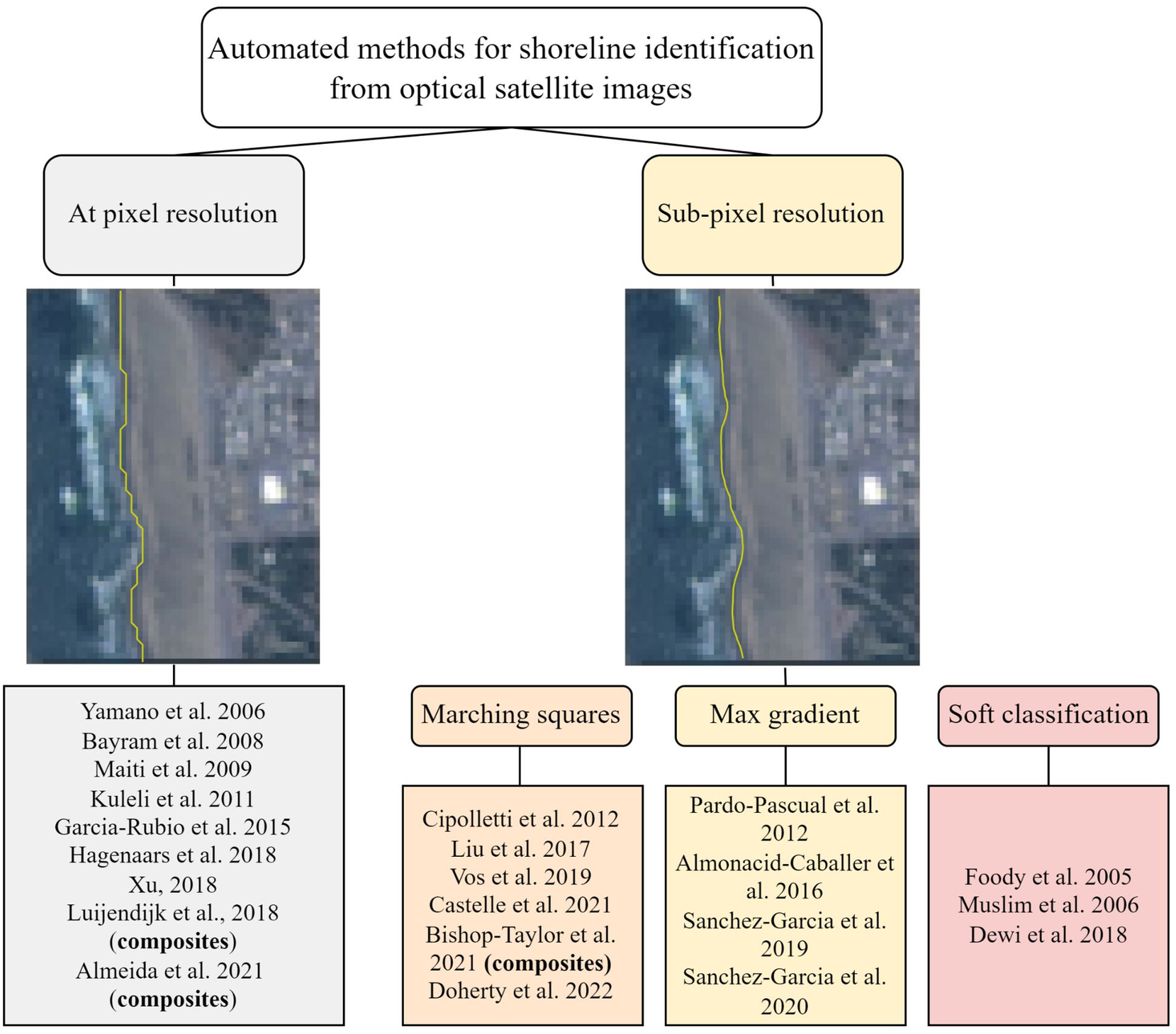

Figure 2 summarizes the variety of satellite-based shoreline detection methods developed in previous literature. These methods can be divided into “at pixel resolution” and “subpixel resolution” categories. As shown on the left side of Figure 2, at pixel resolution methods tend to create a stair-cased waterline. To avoid the “staircase effect” resulting from extracting a contour along individual pixels, a smoother contour can be extracted by integrating the information of neighboring pixels, this can be done using the marching-squares algorithm (e.g., Liu et al., Reference Liu, Trinder and Turner2017; Vos et al., Reference Vos, Harley, Splinter, Simmons and Turner2019a, Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b), a max-gradient method (Pardo-Pascual et al. Reference Pardo-Pascual, Almonacid-Caballer, Ruiz and Palomar-Vázquez2012), or a soft classification (Foody et al., Reference Foody, Muslim and Atkinson2005).

Figure 2. Summary of different methods to automatically map shorelines on optical satellite imagery, including an example of shoreline detection at pixel resolution (left), indicating the “staircase effect,” and at subpixel resolution (right).

Several studies have used composite imagery (Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018; Bishop-Taylor et al., Reference Bishop-Taylor, Nanson, Sagar and Lymburner2021; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Harris, Xie and Phinn2021), which average spatially overlapping images within a time window (e.g., yearly) into a single image. Composite images simplify shoreline mapping by smoothing over dynamic atmospheric (e.g., clouds) and hydrodynamic processes (e.g., tide, wave runup), which obscure and oscillate important features like the water line, respectively. Although composite imagery facilitates mapping long-term shoreline variability (e.g., seasonal to interannual and longer), it also generally precludes mapping of short-term, storm-driven coastal change. Balancing the trade-offs between using smoother, composite imagery versus noisier, synoptic imagery remains an active area of research. However, the trends seem to indicate that synoptic shoreline mapping (even for long-term shoreline change analysis, e.g., Castelle et al., Reference Castelle, Ritz, Marieu, Lerma and Vandenhove2022) is becoming increasingly accurate and attractive.

Vos et al.’s, Reference Vos, Harley, Splinter, Simmons and Turner2019a, Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b CoastSat toolbox derives shorelines from individual satellite images allowing daily to weekly shoreline monitoring. Recently, other publicly available satellite-derived shoreline acquisition and analysis toolboxes have become available (e.g., CASSIE – Almeida et al., Reference Almeida, Efraim de Oliveira, Lyra, Scaranto Dazzi, Martins and Henrique da Fontoura Klein2021). Having dense time-series of shoreline positions from synoptic satellite imagery has enabled derivations of beach slopes (Vos et al., Reference Vos, Deng, Harley, Turner and Splinter2020) and intertidal DEMs (Bishop-Taylor et al., Reference Bishop-Taylor, Sagar, Lymburner and Beaman2019b) from space. Synoptic shoreline mapping from medium to coarse pixel resolution typically translates to 10–15 m accuracy (root-mean-square error) in shoreline position when compared to centimeter-scale in situ observations (e.g., Hagenaars et al., Reference Hagenaars, de Vries, Luijendijk, de Boer and Reniers2018; Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018; Pardo-Pascual et al., Reference Pardo-Pascual, Sánchez-García, Almonacid-Caballer, Palomar-Vázquez, de los Santos, Fernández-Sarría and Balaguer-Beser2018; Vos et al., Reference Vos, Harley, Splinter, Simmons and Turner2019a, Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b). However, recent shoreline-monitoring tools based on high-resolution satellite imagery (3 m/pixel) can provide ~5 m accuracy, which is double or triple the conventional satellite accuracy against in situ observations (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Harley, Vos and Splinter2022). Hence, small form-factor, high-resolution “cubesat” technology (Poghosyan and Golkar, Reference Poghosyan and Golkar2017) and the increased spatiotemporal resolution they provide will likely play an increasingly important role in coastal monitoring. We, the community of coastal scientists, are rapidly approaching a situation in which we will have access to more data (in the form of coastal imagery) than we can readily analyze and ingest with state-of-the-art methods. This situation will increasingly demand advances in the capability and scalability of machine-learning models and the computer system they are run on (as discussed below).

Active sensor satellites

Optical satellites (described above) are passive sensors that record the sun’s reflected light from Earth. Active sensor satellites, on the other hand, emit and record reflected signals. Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites, for example, emit pulses of radio waves at a target scene and record the backscattered signal. Altimetric satellites, for example, ICESat-2, use a form of Lidar for mapping land, vegetation, ocean, and/or icesheet topography. Active sensor satellites offer advantages over passively sensed optical imagery such as the ability to image at night, through cloud-cover, or during extreme storm events. Although these capabilities make SAR and satellite-altimetry promising technologies for monitoring coastal hazards, they are not included in the current review/prospectus, except to say that (in our opinion) they represent extremely intriguing and underutilized tools in monitoring coastal hazards and coastal change. In particular, the prospect of obtaining regular topographic and bathymetric Lidar DEMs from space (rather than from airplanes) is particularly compelling. Although satellite-based Lidar would be unlikely to supplant aerial Lidar for quasi-static urban terrain (at least in the next several years), it could provide a tremendous advantage for observing elevation change across dynamic landscapes like beaches.

Data-driven coastal science using machine learning

As satellite datasets become bigger, the application of modern machine-learning modeling workflows to evaluate Earth surface processes becomes increasingly attractive, particularly as data science workflows become more robust, scalable, and accessible through open-source software (e.g., Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Wernette, Fitzpatrick, Favela, Goldstein and Enwrightin review; Gibeaut et al., Reference Gibeaut, Tissot and Lakshmanan2019; Morgan et al., Reference Morgan, Plant, Stockdon and Snell2019; Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Buscombe, Lazarus, Mohanty, Rafique, Anarde, Ashton, Beuzen, Castagno, Cohn and Conlin2021b; Demir et al., Reference Demir, Xiang, Demiray and Sit2022; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Sandoval, Crystal-Ornelas, Mousavi, Wang, Lin, Cristea, Tong, Carande, Ma and Rao2022). Machine learning is broadly defined as teaching a computer algorithm to learn by example. Among machine-learning frameworks, deep-learning techniques have become particularly powerful for extracting information from imagery (Campos-Taberner et al., Reference Campos-Taberner, García-Haro, Martínez, Izquierdo-Verdiguier, Atzberger, Camps-Valls and Gilabert2020). Deep learning uses large, feedforward neural networks, which employ feature-extraction layers that “learn” to map an input dataset (e.g., imagery) to an output (e.g., more abstract information such as the probability of belonging to a certain category). In coastal science, deep-learning methods are increasingly used to map features such as land-cover type (e.g., sand, water, vegetation) as well as land-cover interfaces such as shorelines (Buscombe and Ritchie, Reference Buscombe and Ritchie2018). In the near future, machine learning will be used in coastal science to extract all types of hydrodynamic and morphodynamic information from satellite imagery (e.g., nearshore wave height/period/direction, runup, grain size, suspended sediment concentration, mineralogy, soil moisture, and river discharge), as well as socioeconomic information such as human interventions at the coast (beach nourishments, etc.), data pre- and post-processing tasks such as data cleaning (e.g., Kim et al., Reference Kim, Huh, Kim, Kim, Yoo and Shim2020) and sensor/data fusion (e.g., Meraner et al., Reference Meraner, Ebel, Zhu and Schmitt2020; Muñoz et al., Reference Muñoz, Muñoz, Moftakhari and Moradkhani2021).

In the following sections, we review a handful of key methods in machine learning that are directly relevant to satellite-based monitoring of coastal environments. Primarily, we focus on techniques that derive data from optical imagery alone, which is by far the most common input to most well-known machine learning modeling frameworks (e.g., supervised convolutional neural networks) across science and engineering.

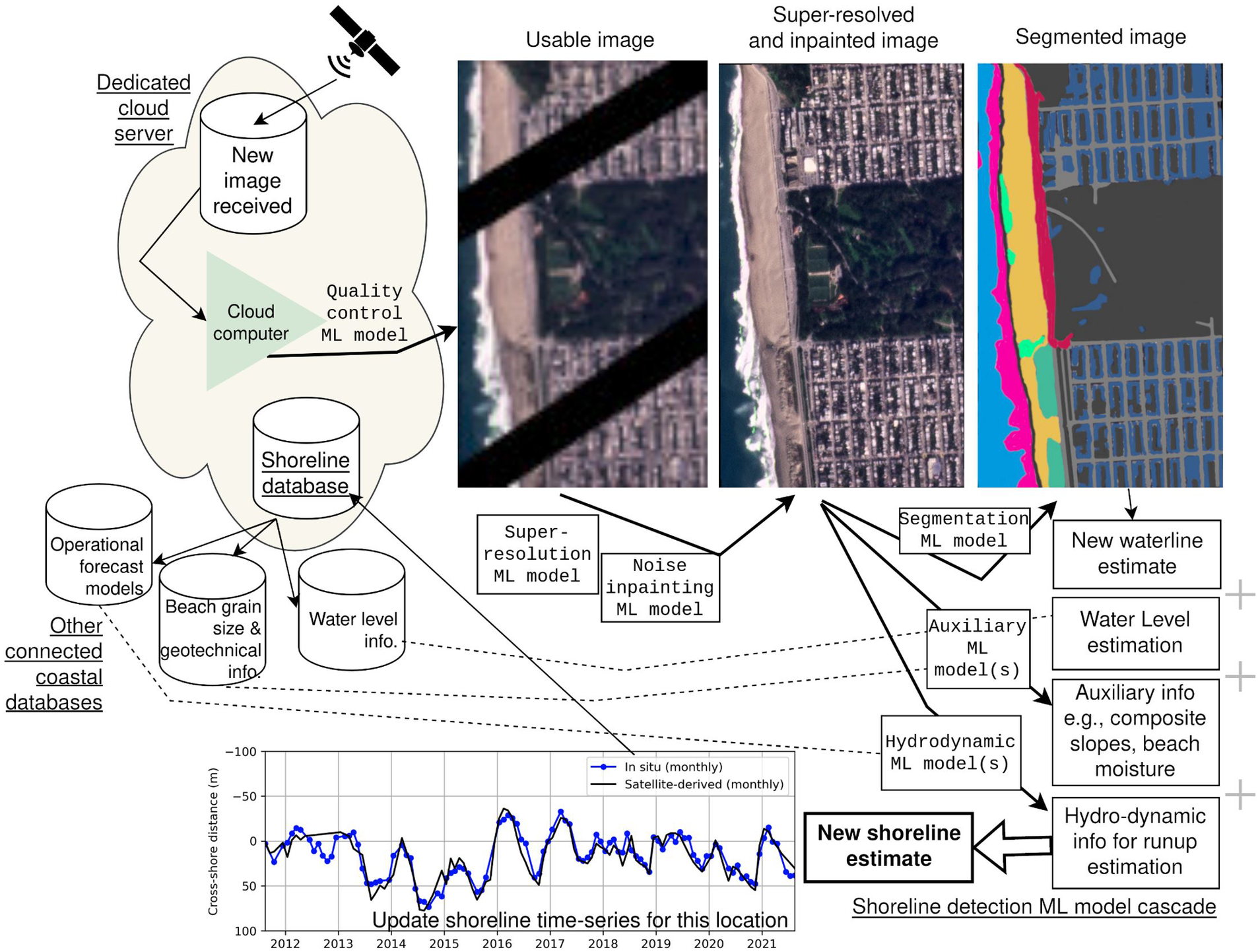

Satellite image classification, segmentation, and regression

A variety of deep-learning-based image segmentation and classification methods have been applied to characterize coastal landforms and covers, sediments, hydrodynamics, shorelines, beach erosional, and morphodynamic states (e.g., Buscombe and Ritchie, Reference Buscombe and Ritchie2018; Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018; Buscombe and Carini, Reference Buscombe and Carini2019; Bishop-Taylor et al., Reference Bishop-Taylor, Sagar, Lymburner, Alam and Sixsmith2019a, Reference Bishop-Taylor, Sagar, Lymburner and Beaman2019b; Vos et al., Reference Vos, Harley, Splinter, Simmons and Turner2019a, Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b; Dang et al., Reference Dang, Bui and Pham2020; den Bieman et al., Reference den Bieman, de Ridder and van Gent2020; Ellenson et al., Reference Ellenson, Simmons, Wilson, Hesser and Splinter2020; Gray et al., Reference Gray, Chamorro, Ridge, Kerner, Ury and Johnston2021; McAllister et al., Reference McAllister, Payo, Novellino, Dolphin and Medina-Lopez2022; Buscombe and Goldstein, Reference Buscombe and Goldstein2022). Image segmentation, whereby each pixel is classified into predetermined classes (e.g., “sand,” “water,” “vegetation”; see Figure 3), facilitates spatially explicit mapping of coastal environments. Image segmentation methods have been useful for estimating landcover types (Buscombe and Ritchie, Reference Buscombe and Ritchie2018), backshore morphology (Mao et al., Reference Mao, Harris, Xie and Phinn2022), roughness for flood models (Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Van Dongeren, Doyle, Hegermiller, Hsu, Kalra, Olabarrieta, Penko, Rafati, Roelvink and van der Lugt2022), mapping flood extents (Bentivoglio et al., Reference Bentivoglio, Isufi, Jonkman and Taormina2021; Erdem et al., Reference Erdem, Bayram, Bakirman, Bayrak and Akpinar2021), flood damage (Adriano et al., Reference Adriano, Yokoya, Xia, Miura, Liu, Matsuoka and Koshimura2021), and economic impacts (Donaldson and Storeygard, Reference Donaldson and Storeygard2016). Segmentation and classification methods can also be slightly modified into so-called "image regression” methods, which provide continuous estimates of quantities of interest (e.g., wave height, Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Carini, Harrison, Chickadel and Warrick2020) or water depth (Collins et al., Reference Collins, Brodie, Bak, Hesser, Farthing, Lee and Long2020). Deep-learning models of continuous variables are inherently stochastic and built with physical properties, which are useful in a myriad of situations where a deterministic model is inadequate or is prohibitively expensive (Simmons and Splinter, Reference Simmons and Splinter2022).

Figure 3. Schematic of a conceptualized, data-driven shoreline-detection workflow using a cascade of machine-learning models. After a new image is available for a location (e.g., Ocean Beach, California, in this example), an initial model determines suitability of the image for processing. Subsequent models carry out image filtering, super-resolution, and inpainting (gap/cloud filling). An image-segmentation model is then used to determine waterline location, which, as well as corrected for tide and other instantaneous variables such as runup, slope, grain size, and so forth, from other machine-learning or data-assimilative models. The outputs from this satellite-based monitoring system could be readily integrated with predictive modeling approaches; see Figure 4.

It is likely that many existing deep-learning models trained from ground-based camera imagery (e.g., for estimating breaking wave height and period, Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Carini, Harrison, Chickadel and Warrick2020; detecting rip-currents, de Silva et al., Reference de Silva, Mori, Dusek, Davis and Pang2021; or detecting wave breaking, Stringari et al., Reference Stringari, Guimarães, Filipot, Leckler and Duarte2021) could be readily adapted to high-resolution satellite imagery. Similar machine-learning models might be constructed for observing/inferring several relevant, continuous variables such as wave runup, beach slope, grain size, or susceptibility to landslides or cliff/bluff erosion from satellite imagery. So far, many deep-learning applications use imagery alone to make predictions without ancillary information, such as waves, tides, or weather. In the future, models will likely be multimodal (Sleeman et al., Reference Sleeman, Kapoor and Ghosh2022), using heterogeneous inputs, such as image/video or scalar/vector/raster, or multiple imagery types (e.g., Guirado et al., Reference Guirado, Tabik, Rivas, Alcaraz-Segura and Herrera2019) or ancillary information (e.g., instantaneous water level or offshore wave predictions) encoded as scalars and vectors (O’Neil et al., Reference O’Neil, Goodall, Behl and Saby2020; Sadeghi et al., Reference Sadeghi, Nguyen, Hsu and Sorooshian2020). The same model features can also be used for multiple classification or prediction targets. A rudimentary example of this is the SediNet model reported by Buscombe (Reference Buscombe2020), which uses the same image features to estimate multiple quantiles of the grain size distribution from an image of sediment.

Supervised and unsupervised learning

All machine-learning models lie somewhere on a spectrum between fully supervised and fully unsupervised. A fully supervised deep-learning approach involves training a large neural network “end-to-end” that explicitly maps user-defined classes (and user-digitized labeled datasets) from imagery. In contrast, fully unsupervised model frameworks infer outputs (such as a class set) from imagery by attempting to uncover patterns, textures, and so forth. However, unsupervised deep neural networks are relatively rare in practice in the current state-of-the-art, plus they still require smaller supervised data for validation purposes, so labeling data is not entirely avoided.

Training supervised models (of coastal landcover, for example) typically involves substantial efforts in labeling, digitizing, and/or categorizing features in imagery using tools like Doodler (Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Goldstein, Sherwood, Bodine, Brown, Favela and Wernette2022) or Coastal Image Labeler (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Buscombe, Lazarus, Mohanty, Rafique, Anarde, Ashton, Beuzen, Castagno, Cohn and Conlin2021b). In general, supervised and semi-supervised machine-learning models are only as good as the label data they are trained with (Geiger et al., Reference Geiger, Cope, Ip, Lotosh, Shah, Weng and Tang2021). At the time of writing, the availability of (analysis-ready) labeled data is perhaps the greatest impediment to the uptake of deep learning among the community of coastal scientists. For the foreseeable future, machine-learning models will continue to require specialized label data for examining specific coastal science questions. Therefore, key to the success of machine-learning applications in the coastal zone will be the creation of commonly labeled datasets that adhere to Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reuse (FAIR) principles (Wilkinson et al., Reference Wilkinson, Dumontier, Aalbersberg, Appleton, Axton, Baak, Blomberg, Boiten, da Silva Santos, Bourne and Bouwman2016). Publicly accessible labeled datasets such as MNIST and ImageNET have become the backbone of deep-learning model development and evaluation. Similarly, large labeled environmental image collections such as BigEarthNet (Sumbul et al., Reference Sumbul, Charfuelan, Demir and Markl2019, Reference Sumbul, De Wall, Kreuziger, Marcelino, Costa, Benevides, Caetano, Demir and Markl2021) that focus on land cover, or the series of SpaceNet datasets that detail infrastructure in satellite scenes, have become the backbone of environmental applications of machine learning. More specialized tasks in coastal science can leverage these large datasets, through image premasking, preclassification, transfer learning, and so forth, but ultimately more powerful data-driven models will inevitably require more specialized labeling in support of specific coastal science or monitoring objectives (e.g., Seale et al., Reference Seale, Redfern, Chatfield, Luo and Dempsey2022). Our ever-increasing reliance on large labeled datasets to train machine-learning models is the primary motivation for developing specialized yet standardized workflows for coastal science applications (e.g., Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Braswell and McShane2021a, Reference Goldstein, Buscombe, Lazarus, Mohanty, Rafique, Anarde, Ashton, Beuzen, Castagno, Cohn and Conlin2021b; Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Wernette, Fitzpatrick, Favela, Goldstein and Enwrightin review).

Spectral unmixing

Spectral mixture models use hyperspectral imagery to infer subpixel composition (e.g., Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Brodrick, Cawse‐Nicholson, Fisher, Pavlick, Small and Thompson2022), especially for medium to coarse (e.g., 10–30 m) resolution imagery. Assuming each pixel contains information about multiple subpixel components (revealed in the reflectance across several spectral bands), a model is created to estimate what proportion of each component is present in each pixel. The model then uses inverse methods to decompose or “unmix” the original signal into proportional fractions of endmembers. To date, numerous proof-of-concept applications in beach and bluff hydrology have been developed to identify grain size (e.g., Bradley et al., 2018; Sousa and Small, Reference Sousa and Small2019), grain mineralogy and rock lithology (e.g., Karimzadeh and Tangestani, Reference Karimzadeh and Tangestani2021), vegetation characteristics (Sousa et al., Reference Sousa, Brodrick, Cawse‐Nicholson, Fisher, Pavlick, Small and Thompson2022), evapotranspiration and surface moisture (e.g., Sousa and Small, Reference Sousa and Small2018), and saltwater intrusion (Werner et al., Reference Werner, Bakker, Post, Vandenbohede, Lu, Ataie-Ashtiani, Simmons and Barry2013), among other processes. Based on the success of spectral unmixing to identify other terrestrial features, we anticipate that this methodology could be expanded to unmixing the hyperspectral signal from coastal environments for making measurements of suspended-sediment concentration, fluvial and submarine groundwater discharge, salinity, chlorophyll, and other tracers, as well as emergent/submerged vegetation, for example.

Image super-resolution

Aside from the inability to image through cloud clover, an important limitation of optical satellite imagery is its spatial resolution. For example, the pixel resolutions of Landsat and Sentinel-derived shorelines are 30 m (15 m when pan-sharpened) and 10 m, respectively. Beaches and other coastal landforms, particularly those in urban settings, are typically narrow (e.g., tens to hundreds of meters in width). Change detection using medium-resolution optical imagery can be hampered when the landform size is only a few pixels wide. Shoreline detection using more recent high-resolution satellite imagery can be two to three times more accurate than low-resolution imagery (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Harley, Vos and Splinter2022). However, the archives of high-resolution satellites often only extend back 5–10 years, in contrast to extending back four decades in the Landsat archive. Using advanced machine-learning techniques to enhance the resolution of individual images will be critical advancement toward making the most out of older and coarser imagery in long-standing archives.

The recovery of a higher-resolution image from its lower-resolution counterpart, known as “image super-resolution” (see Figure 3), is a topic of great interest in satellite remote sensing (e.g., Luo et al., Reference Luo, Zhou, Wang and Wang2017; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Wang, Yi, Wang, Lu and Jiang2019; Dong et al., Reference Dong, Sun, Jia, Xi, Gao and Zhang2020). Image super-resolution will become an increasingly critical tool to enhance old imagery. For example, super resolution will enable greater accuracy and spatial precision of shoreline-detection algorithms and machine-learning model outputs. Deep-leaning (e.g., Kernel-based, convolutional neural network) models, which extract features based on gradients in image intensity, may particularly benefit from super-resolution, because features are better resolved.

Machine-learning models can be trained to learn how to upsample images by matching coincident low- and high-resolution imagery. There are already numerous super-resolution methods, including (1) single-image super-resolution (SISR) that learns the implicit redundancy present in satellite data due to local spatial correlations and recovers missing high-resolution information from a single low-resolution instance (e.g., Shi et al., Reference Shi, Caballero, Huszár, Totz, Aitken, Bishop, Rueckert and Wang2016); (2) reference-based super-resolution (RefSR) that uses high-resolution reference imagery paired with low-resolution imagery (e.g., Yue et al., Reference Yue, Sun, Yang and Wu2013; Ledig et al., Reference Ledig, Theis, Huszár, Caballero, Cunningham, Acosta, Aitken, Tejani, Totz, Wang and Shi2017). We expect to see continued advances in super resolution from generative adversarial network (GAN)-based approaches (described below) that use a pair of models, namely a generator model to produce an upscaled image that is iteratively judged and refined using a discriminator model (e.g., Ledig et al., Reference Ledig, Theis, Huszár, Caballero, Cunningham, Acosta, Aitken, Tejani, Totz, Wang and Shi2017).

Recently, the Landsat Collection 2 was released. Collection 2 is the second major reprocessing effort of the Landsat archive, which applied advancements in data processing and algorithm development for nearly all of the imagery from Landsat 1–9 and the science products from Landsat 4–9. In the future, we could possibly see the release of remastered, high-resolution Landsat collections based on image denoising and super-resolution algorithms (and possibly in combination with spectral unmixing models). Additionally, we could eventually see the release of remastered, cloud-free Landsat collections which apply cloud removal models based on deep learning and data/sensor fusion (e.g., with SAR satellites – see Meraner et al., Reference Meraner, Ebel, Zhu and Schmitt2020).

Generative modeling

Many deep-learning models used for information extraction are discriminative, for example, estimating labels from data. Another class of deep-learning-based models is generative, for example, they generate data (e.g., imagery) from labels. Generative models can also create hyper-realistic depictions of landscapes and seascapes from user-created labels of environmental conditions. Generative modeling has transformative potential for stakeholder and public engagement by enabling photo-realistic depictions of coastal erosion and flooding due to model projections of storms or sea-level rise scenarios. Model-generated polygons, representing future flooding or erosion scenarios, displayed on a map are perhaps not as compelling as stepping into virtual environments and witnessing synthetic yet realistic depictions of possible future flooding and erosion. Synthetic satellite imagery based on map-views of flood/erosion-prone areas may also be compelling visualization for coastal managers and the general public.

Although they are still very much in the research phase, such generative models have already been used to visualize coastal flooding (e.g., Lütjens et al., Reference Lütjens, Leshchinskiy, Requena-Mesa, Chishtie, Díaz-Rodríguez, Boulais, Sankaranarayanan, Piña, Gal, Raïssi and Lavin2021), urbanization (Boulila et al., Reference Boulila, Ghandorh, Khan, Ahmed and Ahmad2021), and disasters such as hurricanes/typhoons (Rui et al., Reference Rui, Cao, Yuan, Kang and Song2021). Conditional generative adversarial networks (cGANs) are capable of generating realistic topography for synthetic landform generation (e.g., Valencia-Rosado et al., Reference Valencia-Rosado, Guzman-Zavaleta and Starostenko2022). We predict that generative models will be used to increase available training data for coastal data-science tasks with minimal manual effort. Future data-assimilative numerical models (described in the following section), combined with GANs, may be able to assimilate satellite images themselves (instead of data products derived therein), generate future predicted landscapes resulting from hindcast/forecasts of physical drivers, and capture feedback between the two.

Integration with operational coastal-change models

In the past several decades, the field of coastal science has increasingly relied on numerical models to assess coastal change and coastal hazards. This reliance makes sense: models are necessary (but not sufficient) tools for prediction. Additionally, this reliance makes sense because models are ubiquitous, while observations are sparse (until recently with the public release of Landsat and Sentinel products). So far, integrated coastal-change modeling and observation systems have remained elusive. Instead, modelers (ourselves included) have used observations “for support rather than for illumination.Footnote 2” Fortunately, with the proliferation of satellite data, we are going to have a lot more observations within our grasp, or, better yet, within our gaze.

Data assimilation

Data assimilation is the bridge that unites the pillars of models and observations for predictions of complex dynamical systems (Fletcher, Reference Fletcher2017). Data-assimilation methods automatically adjust the model state (e.g., the model solution and parameters) during the simulation to best fit any available observations (e.g., shoreline location) via an optimal interpolation that accounts for the uncertainty of both the model and observations. Simply put, if the observations are specified to be of greater uncertainty, the method places more weight on the model and vice versa. Hence, the relative inaccuracy of individual, satellite-derived observations may not severely denigrate the model’s calibration. Data-assimilation methods will weight the model versus observations accordingly, although they may require more observations for convergence. Fortunately, satellites will readily supply those observations with ever-increasing accuracy.

Data assimilation is often credited as the tool that has enabled realistic weather prediction (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, O’neill, Derber and Kamachi2005; Navon, Reference Navon2009). Data-assimilation methodologies are not particularly new. For example, Kalman’s (Reference Kalman1960) “new approach to linear filtering and prediction problems” is more than 60 years old. However, what has really enabled today’s reliable weather predictions is the daily assimilation of millions of satellite observations (Lahoz and Menard, Reference Lahoz and Menard2010).

Although data-assimilation techniques are well established in the fields of atmosphere and ocean modeling, they are relatively new in the coastal geosciences due to the field’s lingering challenge of data sparsity. What’s the point of data assimilation if you do not have much data to assimilate?

Data assimilation methods for coastal change

In coastal science, data-assimilation methods have been applied to problems of bathymetric inversion (e.g., Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Özkan-Haller and Holman2010, Reference Wilson, Özkan-Haller, Holman, Haller, Honegger and Chickadel2014) and shoreline modeling (Long and Plant, Reference Long and Plant2012; Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Limber, Erikson and Cole2017c, Reference Vitousek, Cagigal, Montaño, Rueda, Mendez, Coco and Barnard2021; Ibaceta et al., Reference Ibaceta, Splinter, Harley and Turner2020; Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Antolínez, Beuzen, Bryan, Cagigal, Castelle, Davidson, Goldstein, Ibaceta, Idier, Ludka, Masoud-Ansari, Mendez, Brad Murray, Plant, Ratlif, Robinet, Rueda, Sénéchal, Simmons, Splinter, Stephens, Townend, Vitousek and Vos2020). Although they have been primarily used in hydrodynamic models, data-assimilation methods may be particularly well suited to sediment-transport and morphology models, with many tunable parameters and coefficients that require calibration. Further, when investigating sediment transport on a specific beach, it is hard for models to compete with observations in terms of their relevance and applicability. Although many different types of coastal morphological model exist (Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Antolínez, Beuzen, Bryan, Cagigal, Castelle, Davidson, Goldstein, Ibaceta, Idier, Ludka, Masoud-Ansari, Mendez, Brad Murray, Plant, Ratlif, Robinet, Rueda, Sénéchal, Simmons, Splinter, Stephens, Townend, Vitousek and Vos2020; Ranasinghe, Reference Ranasinghe2020; Toimil et al., Reference Toimil, Camus, Losada, Le Cozannet, Nicholls, Idier and Maspataud2020; Splinter and Coco, Reference Splinter and Coco2021; Sherwood et al., Reference Sherwood, Van Dongeren, Doyle, Hegermiller, Hsu, Kalra, Olabarrieta, Penko, Rafati, Roelvink and van der Lugt2022), it is likely that the “best” model will be one that assimilates the “best” data. For perhaps 99% of the world’s coastlines, satellites are the “best” data, simply because they are the only data, or at least the only suitable time series of data.

The sparsity of coastal observations in space and time has meant that very little data are available for model calibration/assimilation and even less (if any) data are available for model validation. Prolific satellite data enables model calibration and validation. For the first time, we will have the ability to validate model predictions over extremely large scales. Hence, the satellite-based coastal-monitoring renaissance may stimulate a renaissance in model performance or, at the very least, an introspection about the capabilities and limitations of coastal models to resolve real-world behavior.

So far, data-assimilated coastal-change models (e.g., Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Limber, Erikson and Cole2017c, Reference Vitousek, Cagigal, Montaño, Rueda, Mendez, Coco and Barnard2021; Ibaceta et al., Reference Ibaceta, Splinter, Harley and Turner2020; Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Antolínez, Beuzen, Bryan, Cagigal, Castelle, Davidson, Goldstein, Ibaceta, Idier, Ludka, Masoud-Ansari, Mendez, Brad Murray, Plant, Ratlif, Robinet, Rueda, Sénéchal, Simmons, Splinter, Stephens, Townend, Vitousek and Vos2020) have relied on Lidar, GPS, or camera-derived shoreline observations, which has limited their geographic scope and the number of observations available for the models to assimilate. Prolific satellite-derived shoreline observations with high spatiotemporal resolution and coverage would likely increase the amount of available assimilation data in these applications by 2–3 orders of magnitude compared to Lidar/GPS observations. For example, some model domains that previously assimilated 5–10 shorelines will now have 500–1,000 satellite-derived shorelines. As a tradeoff, the accuracy of each satellite-derived shoreline is 2–3 orders of magnitude less than each Lidar/GPS shoreline (e.g., 5–15 m vs. 1–10 cm, respectively). However, we anticipate that the assimilation of high-volume/limited-accuracy satellite-derived shorelines will not severely denigrate model predictions for beaches where satellite observations can provide a reasonable signal-to-noise ratio.

Most data-assimilated coastal-change models (e.g., Long and Plant, Reference Long and Plant2012; Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Limber, Erikson and Cole2017c, Reference Vitousek, Cagigal, Montaño, Rueda, Mendez, Coco and Barnard2021; Ibaceta et al., Reference Ibaceta, Splinter, Harley and Turner2020; Montaño et al., Reference Montaño, Coco, Antolínez, Beuzen, Bryan, Cagigal, Castelle, Davidson, Goldstein, Ibaceta, Idier, Ludka, Masoud-Ansari, Mendez, Brad Murray, Plant, Ratlif, Robinet, Rueda, Sénéchal, Simmons, Splinter, Stephens, Townend, Vitousek and Vos2020) typically rely on sequential methods (e.g., Kalman filtering), where model-state adjustments are performed in sequence, that is, one-after-the-other and at each model time step that is coincident with observations. Sequential data-assimilation methods calibrate models to observations individually in time, and hence they may be considered a “local” (in time) optimization. In contrast, variational data-assimilation methods (a.k.a. 4-DFootnote 3-var) or global optimization methods calibrate models either over a certain time interval of observations or for the entire timespan of observations, respectively. Thus, most existing (sequential) data-assimilated coastal-change models that primarily use data assimilation for parameter estimation, may arguably be better suited to apply global optimization techniques, which will return optimal parameters over the full calibration period. However, looking forward to the future, toward the prospect of integrating satellite observations with operational coastal-change models, the argument swings back toward the preferential use of sequential data-assimilation methods in order to best “reinitialize” the model with nearly instantaneous satellite-derived observations of coastal state.

In the future, we will have operational prediction systems for short/long-term coastal change (as shown in the concept in Figure 4), much like modern-day weather/climatological reports. These prediction systems will be driven by operational atmosphere, ocean, wave, fluvial, and terrestrial models and assimilated with satellite observations. The operational coastal-change modeling system of the future will be integrated with operational coastal-flood models, which will account for coupled feedbacks like beaches acting as buffers against flooding (Barnard et al., Reference Barnard, Erikson, Foxgrover, Hart, Limber, O’Neill and Jones2019). When future beach nourishments occur, the operational monitoring/modeling system will automatically reinitialize the beach to its new, accreted state (as observed from space) and will operationally downgrade the flood risk accordingly. Vice versa, if storm-driven erosion events occur, the operational monitoring/modeling system will upgrade the coastal storm risk posed by subsequent storm events, in order to account for the depleted beach state. The need for coastal, operational monitoring/prediction systems will emphatically grow in tandem with exponential increases in coastal impacts due to sea-level rise in the next few decades (Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Fletcher, Frazer, Erikson and Storlazzi2017a; Taherkhani et al., Reference Taherkhani, Vitousek, Barnard, Frazer, Anderson and Fletcher2020).

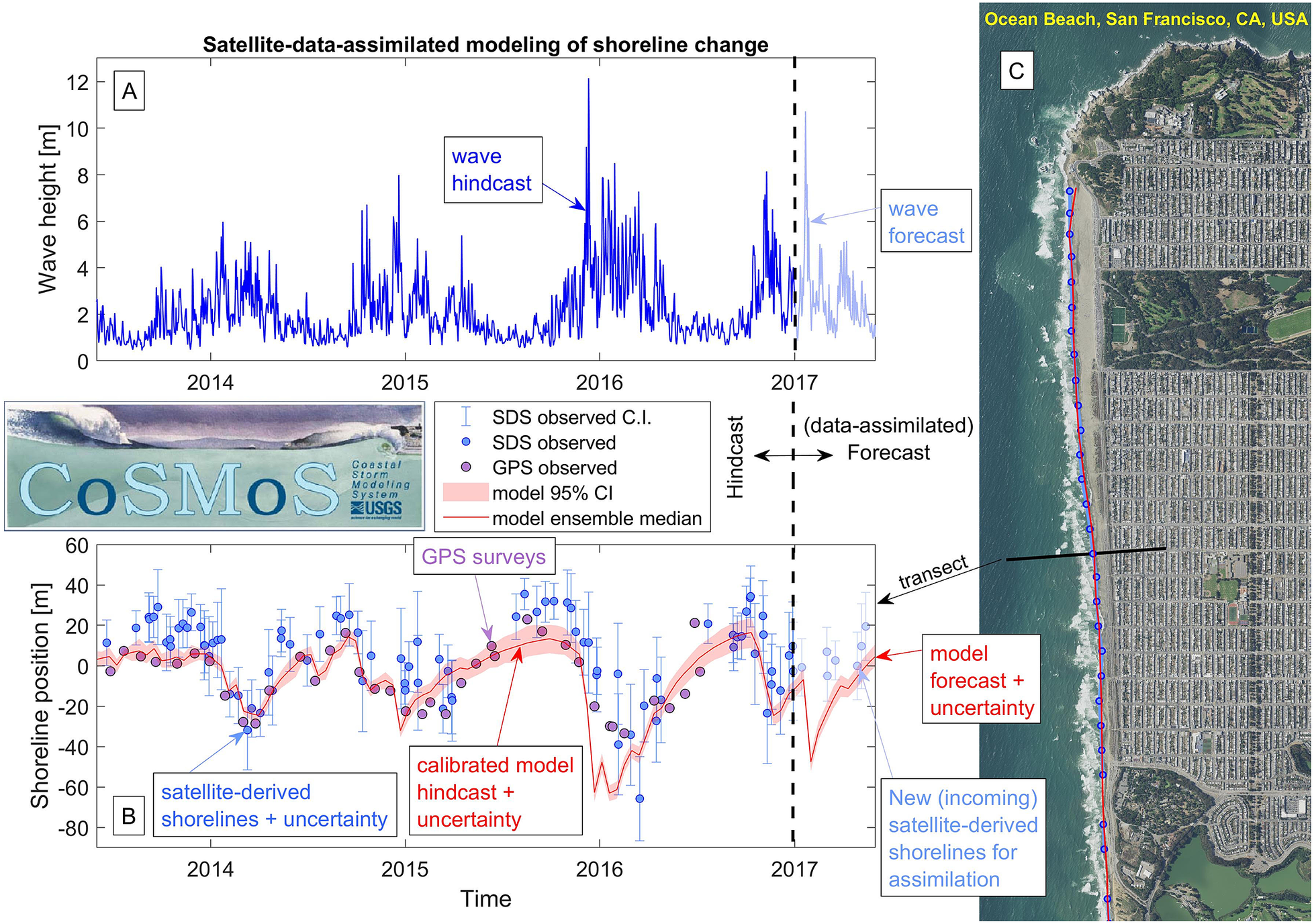

Figure 4. A concept of a satellite-data-assimilated coastal-change modeling system at Ocean Beach, San Francisco, California, USA (Panel C). Panel A shows a time series of significant wave height at this location. The earlier portion of the time series represents a wave hindcast and the later portion represents a wave forecast. Panel B shows a time series of shoreline position (along a shore-normal transect in the middle portion of the beach on Panel C) with GPS surveys (purple dots), satellite-derived shorelines (blue dots) plus uncertainty (blue confidence intervals), and the model-predicted shoreline position (red line) plus uncertainty (pink bands) using the CoSMoS-COAST model (Vitousek et al., Reference Vitousek, Barnard, Limber, Erikson and Cole2017c, Reference Vitousek, Cagigal, Montaño, Rueda, Mendez, Coco and Barnard2021). The black, vertical dashed line (ca. 2017 in this example) represents a transition from a model hindcast to a model forecast, where new, incoming (nearly instantaneous) satellite-derived shorelines will reinitialize the model state to provide an operational prediction of coastal change.

Challenges

There are numerous challenges that future satellite-based coastal monitoring systems will face. First, satellite monitoring is a relatively new concept in coastal science and the accuracy of satellite-derived products (e.g., shoreline positions) is not yet fully understood. Second, satellite-derived products (and the machine learning and other algorithms that produce them) come with their own set of challenges, including (1) data creation/curation challenges and (2) computational challenges, which are somewhat similar (but also somewhat different) than those faced by numerical models. Finally, satellite monitoring will face many lingering scientific questions in coastal science, which have, thus far, remained unanswered.

New developments, technologies, and methods for data collection (e.g., Lidar, coastal cameras) have resulted in tremendous scientific progress in the field of coastal science, but they have not been a “silver bullet” for all problems and all scales. We argue that future satellite-based coastal monitoring systems (despite their limitations) will be the closest thing resembling a silver bullet that the field will ever have to solve our most unyielding, “grand challenge” problems.

Verification

Some in coastal science may doubt the accuracy and applicability of satellite-derived coastal data (e.g., shoreline positions) compared to traditional field-data collection methods. These doubts primarily stem from satellite methods being relatively new, but also over concerns such as the limited pixel resolution and the complexity of nearshore processes, which complicates shoreline identification (among other things). These doubts will be dispelled as the overwhelming utility of satellite observations becomes increasingly apparent.

In the meantime, much work lies ahead to demonstrate the veracity of satellite monitoring methods. Validation efforts will involve the investigation of different components of error, including:

-

• Resolution: The pixel resolution of satellite imagery will remain a critical factor in the accuracy of derived data products (e.g., shoreline position, image segmentation/classification). Existing satellite-derived shoreline-detection methods consistently return root-mean-square errors of roughly half of the image pixel size (e.g., 10–15 m for Landsat, Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018; 3.5–5 m for Planet, Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Harley, Vos and Splinter2022). Yet so far, there has not been a comprehensive assessment of accuracy versus resolution across many satellite missions/platforms using well-monitored field sites. Although there are high-resolution satellites capable of returning decimeter-scale pixels (e.g., WorldView), we anticipate that it is unlikely that the error of shorelines derived therein will be correspondingly low. Instead, other factors (e.g., geo-referencing, wave runup) will likely cause an accuracy bottleneck.

-

• Image coregistration and geo-referencing: The geo-referencing (i.e., the mapping/alignment of imagery to real-world coordinate systems) of satellite imagery is a nontrivial and poorly understood component of error in shoreline monitoring. Most satellites report their own potential geo-referencing errors, which are typically on the order of ~5 m for Landsat. Coregistering images to a base/reference image (via some type of multidimensional scaling while accounting for sensor- and atmospherically derived distortion) may significantly reduce geo-referencing offsets between images, providing greater accuracy and consistency (Doherty et al., Reference Doherty, Harley, Vos and Splinter2022). Yet, the performance of image coregistration methods has not been thoroughly investigated in the context of specific coastal-monitoring objectives.

-

• Machine-vision algorithms: Most algorithms for shoreline detection, geomorphic mapping, change detection, and other tasks are relatively new and were developed for specific coastal settings. As adoption expands, these algorithms will be applied at new, dissimilar sites, which will test their accuracy/robustness. A salient feature of satellite-derived shoreline observations is that they are noisy, compared with in situ, elevation-based surveys. This noise is partly due to wave runup and water-level variations (as discussed below). Other components of shoreline mapping/machine-vision algorithms, like index thresholding, may also play a nontrivial role in contributing to noise/inaccuracy. For example, Doherty et al. (Reference Doherty, Harley, Vos and Splinter2022) found differences in accuracy between Otsu-based thresholding and weighted-peaks-based thresholding, which are conceptually similar methods. In short, we still do not know the best combination of image indices and thresholds to optimally identify the shoreline across a variety of sites, time periods, and tidal reference elevations (e.g., MSL vs. MHW). This knowledge gap is something that must be carefully investigated to improve the robustness/maturity of algorithms over time. Additionally, there are many domain remapping techniques, which, for example, might (1) align imagery from real-world coordinates into along-shore and cross-shore or transect-based coordinates (instead of real-world coordinates), (2) mask out urban or back beach portions of an image to precondition image segmentation algorithms, or (3) enhance (e.g., via super-resolution) targeted features like wave swash or beach nourishments. Although they have yet to see application, there are many existing and emerging filtering techniques (some of which are based on machine learning) that could be applied to de-noise, de-haze, or in-fill satellite-derived shoreline observations, particularly for partially cloudy imagery (Figure 3).

-

• Nearshore processes and water-level corrections: Wave runup (i.e., the wave setup plus time-varying wave swash) is a critical nearshore hydrodynamic process that affects both coastal flooding and shoreline identification in satellite imagery. Many existing satellite-derived shoreline toolboxes (e.g., CoastSat, Vos et al., Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b) correct the instantaneously observed waterline for tidal stage to a standard reference elevation (e.g., Mean Sea Level) but do not correct for wave setup/runup. Hence, the presence of dynamic wave runup remains an important source of uncertainty in shoreline identification (Castelle et al., Reference Castelle, Masselink, Scott, Stokes, Konstantinou, Marieu and Bujan2021). It is possible that wave-driven water-level components, like wave setup, could be corrected for in satellite-derived shorelines. Because wave setup is a persistent water-level component, it may be feasibly corrected for using empirical equations (e.g., Stockdon et al., Reference Stockdon, Holman, Howd and and Sallenger2006). Wave swash, on the other hand, is a dynamic water-level component and thus correcting for it is a more difficult task. It may be possible to obtain an estimate of swash elevation and potentially of swash phase directly from satellite imagery at individual sites via the modification of “optical wave gauging” techniques (e.g., Buscombe et al., Reference Buscombe, Carini, Harrison, Chickadel and Warrick2020) to an “optical runup gauging” technique applied to satellite imagery. However, the impact of swash processes on satellite-based shoreline detection will require further research.

As our reliance on satellite-based coastal monitoring increases, we must not neglect traditional monitoring techniques (Splinter, Reference Splinter, Harley and Turner2018). For example, the majority of machine-learning applications involving satellite imagery require ground-based data for training or verification, or both. Sharing of ground-based data will greatly facilitate the development of data-driven models using machine-learning algorithms, which could be taught to proxy those measurements from satellite imagery. In addition, ground-based measurements are often necessary for beach and dune volume calculations. The continuation of in situ coastal surveys, especially those at regularly monitored sites and leveraged to evaluate our ever-increasing arsenal of remote-monitoring platforms, would be an exceedingly valuable endeavor to improve overall scientific understanding.

Computational challenges

Dealing with large, ever-expanding archives of satellite data will remain an important technical challenge as the resolution of satellite imagery increases. For example, halving the pixel size quadruples the storage requirements. Decimating the pixel size increases the storage requirements by a factor of 100. Additionally, satellite imagery is increasingly available with a growing number of spectral bands, which further adds to the storage requirements. The problem quickly scales to the point where downloading images (to be processed locally) becomes intractable, and it becomes necessary to “send algorithms to the data, not the other way around” (Wulder et al., Reference Wulder, Coops, Roy, White and Hermosilla2018). This problem motivates the need to advance our cloud-computing expertise, where images are stored and analyzed on the cloud. Satellite-based remote sensing and cloud computing will become increasingly important components of the training/curriculum for the next generation of coastal scientists. Even with state-of-the-art training and access to cloud-hosted solutions, the question remains as to whether or not the firehose of daily incoming satellite data will outpace our ability to interpret those data.

Both numerical and machine-learning models have benefited greatly from exponential increases in computational power. Many of the (pretrained) machine-learning algorithms used in existing satellite toolboxes require fairly minimal computational effort, except when being deployed at large scales (e.g., over ~1,000 km). However, as image spatial resolution improves, the number of spectral bands increase, and additional pre- and post-processing routines become necessary (e.g., image super-resolution, image coregistration, image remapping to shore-normal coordinate systems, improved segmentation, machine-learning-based water-level corrections, filtering/smoothing, NaN-infilling), then computational costs will necessarily increase to pay for the higher accuracy received. There must always be a three-point balance between computational cost, accuracy, and spatial/temporal scale. We argue that satellite monitoring efforts should ideally tip the scales in favor of large-scale applications, since scalability is and will always be the greatest advantage of satellites over traditional coastal-monitoring systems.

As accessibility to cloud computing improves, our focus should be on creating a suite of web-enabled software tools for data labeling, modeling, and model verification tailored to the specific needs of coastal researchers and resource managers. In the meantime, easy-to-use platforms like Google Earth Engine, a cloud-computing solution for local delivery and/or cloud processing of satellite data, have enabled several notable applications in water science (e.g., AquaMonitor, Donchyts et al., Reference Donchyts, Baart, Winsemius, Gorelick, Kwadijk and Van De Giesen2016; Dynamic Surface Water Extent, Soulard et al., Reference Soulard, Walker and Petrakis2020) and coastal science (e.g., ShorelineMonitor, Luijendijk et al., Reference Luijendijk, Hagenaars, Ranasinghe, Baart, Donchyts and Aarninkhof2018, CoastSat, Vos et al., Reference Vos, Harley, Splinter, Simmons and Turner2019a, Reference Vos, Splinter, Harley, Simmons and Turner2019b). Conventional wisdom indicates: if data are easy to access, then they are used. Following this logic, the adoption/use of high-resolution optical and SAR imagery will be much slower and uneven if data are hidden behind a paywall. Data access/costs will dictate the adoption rates of high-resolution satellite products. High costs of high-resolution imagery (per square km) may pigeon-hole many applications into being small-scale, which is the very drawback that we hoped the satellites would overcome. Hence, publicly available satellite imagery such as currently available from Landsat and Sentinel will likely always play a commanding role in scientific research.

Scientific challenges

It has been long understood that water-level observations recorded at a single tide gauge cannot provide a broad understanding of global sea-level rise. Instead, decades of observations across hundreds of distant tide gauges are necessary to provide consensus on sea-level rise. Better yet, tide gauges in combination with decades of satellite altimetry data (i.e., observations of sea surface height from radar satellites like Topex/Poseidon, Jason-1,2,3) provide the necessary and sufficient data to demonstrate, without ambiguity, that global sea level is rising and accelerating, as has been demonstrated in the most recent IPCC (2021) and U.S. (Sweet et al., Reference Sweet, Hamlington, Kopp, Weaver, Barnard, Bekaert, Brooks, Craghan, Dusek, Frederikse, Garner, Genz, Krasting, Larour, Marcy, Marra, Obeysekera, Osler, Pendleton, Roman, Schmied, Veatch, White and Zuzak2022) sea-level-rise reports.

For many reasons, a similar mentality about the need to form consensus using global-scale observations is perhaps not as prevalent within the coastal-change community. Instead, we rely on “scalability by analogy,” namely, that the study of one site will inform the fate of another (under the assumption of the universality of the underlying sediment transport and morphologic processes). Arguably, we have not possessed the scale of data sufficient to take the alternative “scalability-by-volume” approach … until now. With prolific satellite-derived shoreline observations, we can begin to form a local-to-global consensus about the drivers and fate of coasts worldwide.

Satellite observations are ideally suited to address critical knowledge gaps about multidecadal drivers of coastal change. For example, Barnard et al. (Reference Barnard, Short, Harley, Splinter, Vitousek, Turner and Heathfield2015) investigated patterns of coastal change due to climatic cycles (e.g., El Niño–Southern Oscillation) at 48 sites around the Pacific. Armed with almost four decades of satellite observations, a similar analysis might be conducted spanning the Pacific Rim. In addition to wave-driven, cross-shore beach response, multidecadal changes in wave and storm patterns can affect gradients in longshore transport (e.g., Slott et al., Reference Slott, Murray, Ashton and Crowley2006; Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Ruggiero, Antolínez, Méndez and Allan2018), which often represent the strongest drivers of long-term coastal change.

Although many more critical knowledge gaps exist than can be discussed here, we highlight an important trio of challenges (which focus primarily on the long-term sustainability of coasts): (1) coastal recession due to sea-level rise, (2) the lifespan of nourishments and the sustainability of urban coasts, and (3) large-scale fluvial sediment supply from watersheds to beaches.

The “Bruun rule” (Reference Bruun1962) is a widely used and widely criticized model to quantify shoreline recession due to sea-level rise (Wolinsky and Murray, Reference Wolinsky and Murray2009). Both its widespread use and widespread criticism stems from the precision at which it quantifies coastal recession, namely

![]() $ R=S/\tan \alpha $

, where

$ R=S/\tan \alpha $

, where

![]() $ S $

is the sea-level rise and

$ S $

is the sea-level rise and

![]() $ \tan \alpha $

is the average beach slope from the depth of closure to the top of the upper shoreface. The accuracy of the Bruun rule, on the other hand, is somewhat suspect (Cooper and Pilkey, Reference Cooper and Pilkey2004). It is often hard to directly and unambiguously attribute erosion to small amounts of sea-level rise among so many other simultaneous coastal-change processes (e.g., waves/storms, sediment sources/sinks). The underlying mechanism of the Bruun rule, namely the upward and landward migration of beaches to maintain an “equilibrium” elevation profile shape due to sea-level rise, is generally not hotly debated, and the model endures because there is “no simple, viable alternative” (Rosati, Reference Rosati, Dean and Walton2013). Convincing validation studies of the Bruun rule have been carried out in both laboratory (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Baldock, Birrien, Callaghan, Nielsen, Beuzen, Turner, Blenkinsopp and Ranasinghe2018) and field (Troy et al., Reference Troy, Cheng, Lin and Habib2021) settings. Although the task of verifying the Bruun rule is hard on open-ocean coasts, where historical sea-level rise has been slow (e.g., on the order of 2–3 mm/year), it is more tractable in lakes. Using remote sensing techniques, Troy et al. (Reference Troy, Cheng, Lin and Habib2021) found that ~1 m of lake-level rise (over the course of a decade) resulted in ~30 m of coastal recession at beaches on Lake Michigan. This amount of recession was nearly triple that expected from the passive inundation of a static beach profile (i.e., ~10 m), but about half of the recession was expected from the unmodified Bruun rule (i.e., 60 m). Although certain lakes currently serve as a model environment for testing shoreline recession due to water-level trends, the world’s oceans will soon follow suit. According to the latest NOAA sea-level rise report (Sweet et al., Reference Sweet, Hamlington, Kopp, Weaver, Barnard, Bekaert, Brooks, Craghan, Dusek, Frederikse, Garner, Genz, Krasting, Larour, Marcy, Marra, Obeysekera, Osler, Pendleton, Roman, Schmied, Veatch, White and Zuzak2022), we can expect ~1.1–2.1 m of sea-level rise by 2100 (if emissions are not curbed). Over the next several decades, satellites will allow us to observe (on a global scale) the relationship between sea-level rise and coastal recession. The ratio of sea-level rise and the shoreline recession rate is sometimes called the “transgression slope” (e.g., Wolinsky and Murray, Reference Wolinsky and Murray2009), and satellite-derived shoreline observations might illuminate if it scales with (1) the average beach slope (i.e., the classic Bruun rule), (2) the inland beach slope (i.e., the passive inundation model), or (3) some landscape-dependent middle ground. Hence, we offer the issue of sea-level-driven coastal recession as the first “grand-challenge” problem for both coastal science and society, and we propose that satellite-derived shoreline observations will be the critical factor in solving it.

$ \tan \alpha $