Introduction

Talking about death and dying with patients with advanced diseases is an important clinical task. It allows patients to make choices regarding their treatment, to set realistic goals, to mourn and come to terms with the end of life, to experience greater satisfaction with care, and to have a better quality of life (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Kools and Lyndon2013; Brighton and Bristowe Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016; Wright Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008). Yet, evidence shows that physicians are reluctant to have discussions about poor prognosis and death (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Kools and Lyndon2013; Brighton and Bristowe Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016; Mack and Smith Reference Mack and Smith2012; Wright Reference Wright, Zhang and Ray2008). Several barriers that hinder physicians in communicating about death and dying with patients and their relatives have been reported, such as prognostic uncertainty (Epstein Reference Epstein2021), fear of inducing depressive disorders, lack of training for this task, anxiety (Stiefel and Krenz Reference Stiefel, Krenz, Surbone, Zwitter, Rajer and Stiefel2013), and emotional pain experienced by physicians (Brighton and Bristowe Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016; Horlait et al. Reference Horlait, Chambaere and Pardon2016; Mack and Smith Reference Mack and Smith2012).

The wish not to take away hope is another reason as to why physicians avoid addressing end-of-life issues (Brighton and Bristowe Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016; Horlait et al. Reference Horlait, Chambaere and Pardon2016; Mack and Smith Reference Mack and Smith2012; Wenrich et al. Reference Wenrich, Curtis and Shannon2001). Hope has long been recognized as a key component of coping with an illness (McClement and Chochinov Reference McClement and Chochinov2008), and it negatively correlates with depression and anxiety (Olver Reference Olver2012). The claim of the importance of maintaining a positive attitude and of “thinking positive” is also widespread among seriously ill patients (Wilkinson and Kitzinger Reference Wilkinson and Kitzinger2000). Evoking death may thus be viewed as conflicting with coping strategies, hope, and thinking positively. However, studies show the opposite: a physician’s honesty may help patients to feel more hopeful (Daneault et al. Reference Daneault, Lussier and Mongeau2016). Most patients and their families want to talk about death and dying (Parker et al. Reference Parker, Clayton and Hancock2007) and prefer that the subject is raised in an honest and straightforward manner (Ebenau et al. Reference Ebenau, van Gurp and Hasselaar2017; Wenrich et al. Reference Wenrich, Curtis and Shannon2001). Moreover, research by Emanuel et al. (Reference Emanuel, Fairclough and Wolfe2004) indicates that talking with terminally ill patients and their caregivers about death, dying, and bereavement is rather helpful than stressful. Avoiding these issues may be relieving in the short term but may increase patients’ distress in the long term and deny them the opportunity to share their fears and worries (Fallowfield et al. Reference Fallowfield, Jenkins and Beveridge2002), to be with their families, and to engage in activities that are important to them, given they spend more time in the hospital (Harrington and Smith Reference Harrington and Smith2008). Somehow disappointingly, Tate (Reference Tate2020) found that physicians may invoke death to leverage their professional authority and push patients toward accepting a particular treatment course.

Many articles on communication about death in cancer care focus on how oncologists deliver prognostic information (Chou et al. Reference Chou, Hamel and Thai2017; Henselmans et al. Reference Henselmans, Smets and Han2017; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2008). Most of the time patients initiate the discussion, and when physicians do it, they are often vague and use ambiguous language (Henselmans et al. Reference Henselmans, Smets and Han2017). Moreover, oncologists tend to simultaneously use explicit and implicit language (euphemistic or indirect talk) in an attempt to mitigate the effects of their message and to avoid hurting the patient (Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2007). When the topic of death appears in the discussion, physicians rapidly switch the subject to address treatment options (Chou et al. Reference Chou, Hamel and Thai2017), and when prognostic information is discussed, they focus on the uncertainty of the prognosis (Henselmans et al. Reference Henselmans, Smets and Han2017). Less studied is the physicians’ discomfort with death (Mori et al. Reference Mori, Shimizu and Ogawa2015; Rodenbach et al. Reference Rodenbach, Rodenbach and Tejani2016). Rodenbach et al. (Reference Rodenbach, Rodenbach and Tejani2016) showed how awareness of personal mortality may help clinicians to discuss death more openly with patients and to provide better care. According to Granek et al. (Reference Granek, Krzyzanowska and Tozer2013), oncologists’ discomfort with death and dying is one of the barriers to communication about the end of life, along with, for instance, lack of experience, diffusion of responsibility among multiple physicians, and lack of mentorship.

The present study aimed to investigate communication about death in follow-up consultations intended to discuss the results of the investigation documenting the spread of the disease with patients undergoing chemotherapy with no curative intent. We examined this issue from 3 perspectives, namely (i) how the topic of death was approached in the consultations, who raised it, in what way, and how oncologists and patients interacted when death appears in the discussion, (ii) how the topic unfolded during consultations, and (iii) whether interaction patterns or ways of communicating can be identified when they talked about death and dying.

The approach offered by this article is complementary to that of Henselmans et al. (Reference Henselmans, Smets and Han2017), who examined how communication about life expectancy is initiated with advanced cancer patients and what kind of prognostic information is presented.

Methods

Material

The material used for this study consisted of 134 audio-recorded and transcribed consultations of 24 oncology physicians with 134 patients with advanced cancer. This material was collected as part of a naturalistic multicenter observational study conducted in Switzerland (Vries et al. Reference De Vries, Gholamrezaee and Verdonck-de Leeuw2017); the study received approval from the ethics committee of the participating hospitals, and patients signed an informed consent form. The objective of these follow-up consultations was to discuss the results of investigations such as CT scans and tumor marker levels, effectuated to document the spread of the disease.

The duration of the recordings ranged from 5.27 min to 72.54 min (median of 26.32 min). After listening to the recordings, we excluded 13 because of mediocre sound quality and 61 because death was not discussed at all. The dataset for analysis consisted of 60 consultations.

Data analysis

We used a framework of sensitizing concepts from a literature review concerning end-of-life communication in palliative care (Parry et al. Reference Parry, Land and Seymour2014); communication about life expectancy in cancer care (Chou et al. Reference Chou, Hamel and Thai2017; Graugaard et al. Reference Graugaard, Rogg and Eide2011); the language used by oncologists to talk about death and dying (Lutfey and Maynard Reference Lutfey and Maynard1998; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2007); and coping strategies of cancer patients (Salander et al. Reference Salander, Bergknut and Henriksson2014; Wilkinson and Kitzinger Reference Wilkinson and Kitzinger2000). These concepts suggested “directions along which to look without prescribing what to see” (Bombeke et al. Reference Bombeke, Symons and Vermeire2012; Bowen Reference Bowen2006). A thematic analysis was performed on the transcripts of the 60 consultations (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006), the data analysis being both deductive, relying on the framework, and inductive, not restricted by it. The thematic map included a final set of themes (i) on ways used by oncologists, on the one hand, and patients, on the other hand, to address death and (ii) on responses used by oncologists and/or patients (see Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Ways of addressing death and dying

Table 2. Responses to the death talk

The framework and the analyses led to distinguish the use of direct from indirect language when discussing death. We used a broad definition of direct language related to death, which includes the word “death” and its synonyms, expressions commonly used to talk about death, such as “to kick the bucket” or “to be doomed,” euphemisms, such as “to be gone,” “to pass away,” and expressions unequivocally linked to the subject of death, such as “settling the affairs” or “enjoying the time left.” We considered as an indirect language the themes that may be, but are not necessarily, related to death. For example, when patients talk about their fears and anxieties about the disease and its progression, we can assume the presence of death anxiety but without being absolutely sure.

Moreover, the analysis at the level of the consultation made it possible to identify patterns of interaction, namely specific and recurring combinations of coding categories.

Results

In the following subsections, we provide illustrative excerpts for some of the results. The choice was balanced between excerpts that are very illustrative of a certain aspect and excerpts that help to understand the meaning of a result. In the excerpts, the bolded passages are elements that contributed most to the coding. However, the context was always taken into consideration and the coding was not based on an isolated passage.

In the body of the text, themes are in italics to facilitate reading and understanding.

Approaching the subject of death

When direct language about death was used, the subject was most often initiated by patients (in 23 of 33 consultations). Patients raised it in different ways, for instance by talking about the seriousness of their illness (excerpt 1, Table 3), the death of a loved one (excerpt 2, Table 3), the desire to stop treatment or their resources and life philosophy (excerpt 3, Table 3).

Table 3. Raising the subject of death

Note: The passages in italics are elements that contributed the most to the coding.

ONC = Oncologist; PAT = Patient.

Oncologists initiated death talk less often, and when they did, with less variety, they focused, for instance, on the disease severity and existing treatments, as illustrated in excerpt 4 (Table 3).

In response to the talk initiated by patients, oncologists showed, in contrast, a wide range of responses. These responses ranged along a continuum from avoiding the subject of death, medical and relational reassurance (excerpt 5, Table 4) to asking for clarification (excerpt 6, Table 4), and disagreeing. The densest response from the oncologists was the exploration of the patient’s resources.

Table 4. Responses to the death talk

Note: The passages in italics are elements that contributed the most to the coding.

ONC = Oncologist; PAT = Patient.

When oncologists initiated death talk, patients showed little variety in their responses and sometimes did not have room to answer and to engage in the discussion. They also asked for clarification or agreed without continuing the discussion.

Talking about death throughout consultations

In the consultations, the subject of death was addressed once or several times. In most consultations (in 19 of 33 consultations), direct talk about death was initiated only once, giving rise to a unique interaction between the oncologist and the patient/relatives. We identified 2 interactions associated with the subject of death in 7 consultations and 3 to 5 interactions in 7 consultations. In the latter consultations, oncologists approach the subject of death from different perspectives, such as emphasizing the seriousness of the threat posed by cancer, encouraging patients to take advantage of the limited amount of time they have left to live, or reminding them to settle their affairs. When patients addressed death, they also did it from diverse perspectives, but there is an asynchrony between them and oncologists. Indeed, oncologists and patients did not raise the subject of death at the same time of the consultation, and their attempts to talk about it were unsuccessful. Therefore, the discussion about death unfolded in distinct, successive steps, as illustrated by the following excerpt (excerpt 7, Table 5) of a consultation with a patient having colon cancer. He was informed in a previous consultation that his current treatment is the last possible option. The purpose of this consultation is to discuss the results of a CT scan, which shows no liver or bone metastasis but an important, progressive, peritoneal carcinosis. Therefore, the oncologist informs that the treatment should be stopped because it is of limited benefit.

Table 5. Talking about death throughout consultations

Note: The passages in italics are elements that contributed the most to the coding.

ONC = Oncologist; PAT = Patient.

Interaction patterns

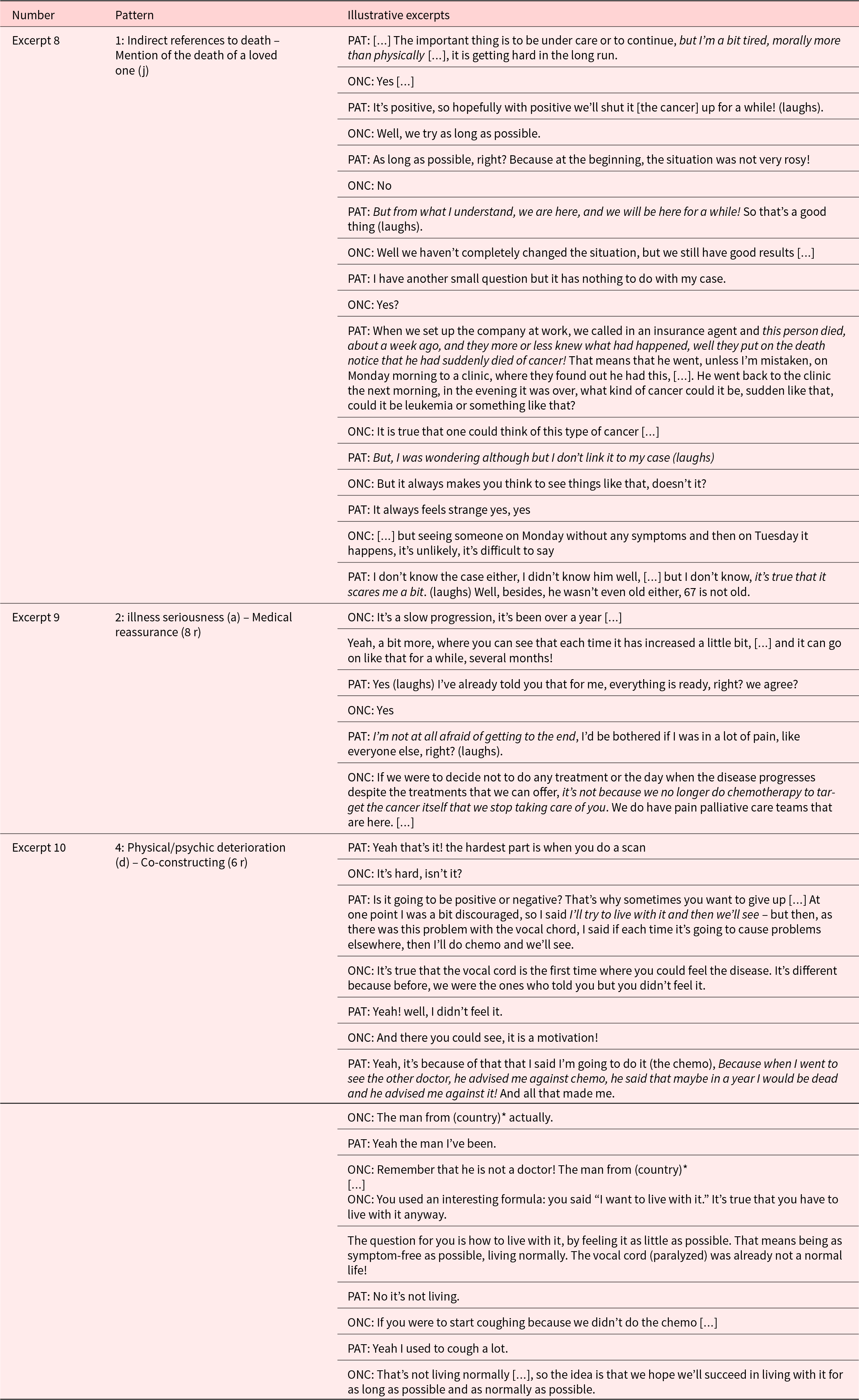

Oncologists and patients/relatives approached the subject of death in various ways in our material, among which we identified 4 specific patterns, i.e., a regularly repeated arrangement of ways of communicating and themes.

The most frequent pattern (pattern 1) consisted of several indirect references to death by patients, followed by a direct mention by the patient of the death of a loved one and a statement of the oncologists aiming to skip the subject. In the interaction pattern 1, the indirect references to death by patients throughout the consultation expressed their concerns and worries in 3 different ways: either emotionally, verbally, by discussing prognosis, or relationally, by seeking reassurance from their oncologist (excerpt 8, Table 6). Given the lack of response by oncologists, patients displaced the topic of their own death to the death of another person without a further response from the oncologists.

Table 6. Interaction patterns

Note: The passages in italics are elements that contributed the most to the coding.

ONC = Oncologist; PAT = Patient.

2 includes statements in which patients raised the subject of death by pointing to the seriousness of their illness and oncologists responded by a rationalization – they explained the situation in a rational or logical manner (excerpt 7 part 1, Table 5) – or reacted with medical reassurance – providing facts and statistics to remove fears and concerns about the illness (excerpt 9, Table 6).

Pattern 3 begins with oncologists talking about stopping treatment since they no longer have any effect. In response, patients asked for clarification with regard to the continuation of care (see excerpt 4, Table 3). Such clarification may reflect patients’ difficulty to accept the limits of treatment or an implicit call to discuss the issue of death and dying, but also a lack of understanding of the next step of the care process.

In the last pattern we identified (pattern 4), patients talked about the physical and/or psychic deterioration caused by their cancer, and oncologists co-constructed with them by complementing what they said and thus providing support to continue to elaborate. This pattern was the only one in which oncologists entered into a discussion with patients about death and encouraged them to address the subject (excerpt 10, Table 6).

Discussion

We discuss the results in the same order as that of the results section: by whom and how the issue of death was raised and which responses were elicited; how death was discussed throughout the consultations; and, lastly, what kind of interaction patterns were observed.

First, with regard to raising the subject of death, patients usually took the initiative. This finding is consistent with those of other studies, such as Henselmans et al. (Reference Henselmans, Smets and Han2017) who examined communication about life expectancy. Similarly, it has been observed in other settings than oncology that physicians await the initiative of patients to talk about the end of life (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Kools and Lyndon2013; Pino et al. Reference Pino, Parry and Land2016). We confirm this observation for the oncology setting. It may be that physicians want to respect patients’ desires concerning the timing and content of end-of-life discussions (Brighton and Bristowe Reference Brighton and Bristowe2016) or they do not want to harm, but it may also be that physicians are not comfortable talking about this issue and thus avoid it completely. In a study about the prognostic talk, Mack and Smith (Reference Mack and Smith2012) suggested that physicians are reluctant to discuss life expectancy because they think it would depress patients, take away hope, and not be culturally appropriate in certain situations and because it is stressful and hard for physicians to address the subject. We can assume that these reasons also explain the lack of initiative of oncology physicians when it comes to addressing death.

While previous studies have focused on who started end-of-life discussions, our study goes a step further and elucidates how patients raise the subject of death and how oncologists respond to it (and vice versa). Patients find various possibilities to talk about death. The patient’s frame of reference extends to life in general, it relates to the “voice of the lifeworld,” which Mishler contrasted with the “voice of medicine” (Mishler Reference Mishler1984). Indeed, relying on their frame of reference, patients addressed death, for instance, through their philosophy of life, the seriousness of their condition, the mention of the death of a loved one, or their desire to stop treatment. By addressing the severity of the disease, patients may also use the medical frame of reference to adjust to physicians, who they feel do not respond to other attempts to talk about death. The patients’ strategies to address the issue of death often follow indirect strategies, indicating a certain level of discomfort.

On the other hand, oncologists’ frame of reference to talk about death is also more limited. They show only a few ways to initiate communication about death, which are restricted to the medical domain, focusing on the severity of the disease and remaining treatment options. This observation is in line with research on prognostic communication, which demonstrated that physicians tend to shift directly from prognostic talk to treatment options (Chou et al. Reference Chou, Hamel and Thai2017) or to address treatment-related prognostic rather than disease-related prognostic (Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2008). Moreover, when the subject of death is raised, biomedical rather than psychological issues are discussed (Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2007). This is also consistent with our results. One can consider this “retreat” on safe medical grounds as a defensive reaction induced by anxiety provoked by the topic of death. Indeed, we have already observed this maneuver, associated with defenses such as rationalization and intellectualization, in our clinical work (Stiefel and Krenz Reference Stiefel, Krenz, Surbone, Zwitter, Rajer and Stiefel2013) and in empirical research on patient–oncologist communication (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, de Roten and Despland2010). While defenses have an anxiolytic and protective function, be it in physicians or patients, they might also be a source of alienation between patients and health-care professionals and lead to unmet needs. In other words, if such defensive reactions during the consultation only serve the needs of the physicians, they may do harm. While a prudent attitude in medicine is generally a good advice, this counts also for communication about sensitive issues. Perceiving when a patient is ready to discuss issues related to death and dying and when the right moment appears is most important. However, ignoring patients’ cues, not engaging in a discussion a patient initiates, or relaying solely on indirect, medically centered ways to address issues of death and dying are witness of a malaise and not a prudent medical attitude.

In terms of the response provided, the range of oncologists’ replies is much wider and that of the patients more limited. This might be because oncologists follow patients with their wider frame of reference. The observation that physicians adjust to patients’ lead has been reported in another study, demonstrating that physicians respond explicitly when patients make an explicit comment about death (Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2007). Oncologists might also be more comfortable discussing death from different perspectives once patients have clearly shown their willingness to address the subject. Oncologist’s responses, however, rarely aim at exploring the patients’ thoughts and emotions but – when they do not ignore patients’ wish to address the subject of death – consist of medical or relational reassurance (in quite general terms) or clarifications of the patients’ statements. Of course, there is no answer to death and existential issues, but it is often not so much a question to provide an answer, as physicians are trained to do, but to hear and understand the interrogations and associated emotions patients have. Feeling understood even without receiving an answer is a way to relate and to diminish loneliness, which patients often feel when facing existential threat (Stiefel and Krenz Reference Stiefel, Krenz, Surbone, Zwitter, Rajer and Stiefel2013). On the other hand, the patients’ restricted range of responses, if they receive room to respond, consist of strategies such as clarification or agreement, which can probably be understood within the larger context of the physician–patient relationship, characterized by a certain dependency, that invites patients to adopt a patient role.

Second, with respect to talking about death throughout the consultation, the results show that the subject of death was usually raised only once and that the “discussion about death” tends to be more than short. Graugaard et al. (Reference Graugaard, Rogg and Eide2011) observed that “prognostic talk in hematology and rheumatology most often occurs in segments of small duration, sometimes repeated throughout the consultation.” This appears also to be the case in the oncology setting, as suggested by our results. Even in the small number of consultations where the issue of death was raised several times, there was no extensive discussion about death. One hypothesis is that oncologists and patients do not have the same agenda with respect to death talk, and when one of them raises the subject, the other is surprised and remains stuck to his/her agenda. In this regard, a study has shown that if patients take the initiative of talking about death early in the consultation, physicians often redirect toward history taking (Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Gambino and Butow2007). Discussions with patients, however, should ideally unfold as a dance, a dialogue, in which responses to each other’s interrogations harmoniously evolve over time. However, when it comes to death, the very existential nature of the issue for which only the concerned individual may find a way to cope with disrupts a dialogue, which is usually maintained when talking about medical matters.

Lastly, 4 interaction patterns were identified. In pattern 1, when patients mentioned the death of a loved one after several indirect references to death and dying, thus showing an openness to the subject of death, oncologists often responded by avoiding the subject of death. The evocation of the deceased loved one, who is invited to the consultation as a third party, can thus be understood as a way of materializing death after having repeatedly spoken of death allusively. It is as if the patients finally say “and yet death exists!” The continuing nonresponse of the oncologists is in line with what we discussed with regard to the existential nature of death.

When patients indirectly talk about death by statements about the severity of the disease, oncologists tended to rationalize the subject or to provide medical reassurance (pattern 2). This might be the expression of physicians’ defenses (rationalization is among the mature defense to decrease anxiety (Bernard et al. Reference Bernard, de Roten and Despland2010)) or of their desire to provide solutions. Referring to development, one could say that existential issues emerging between child and parents, such as separation and associated emotional pain, require a “marked response” (Benjamin Reference Benjamin2002). Marked response means that a parent does not exactly feel what the child feels in such a moment, but that the parent is affected by the child’s experience without being emotionally overwhelmed and able to signify to the child that he or she “knows how it feels.” Marked responses were not observed in our material.

When physicians indicate that treatments should stop, patients ask for clarification (pattern 3), which may illustrate that it is not necessarily clear for patients that stopping treatments implies a progression of the disease and, ultimately, death. This clarification request might also be an expression of patients’ denial of the gravity of the situation. Here again, the marked response acknowledging the limits of medical power and the sadness or frustration that cure is not possible anymore has again not been observed in the studied consultations.

Finally, in pattern 4, patients addressed death by pointing to the endured physical and/or psychological exhaustion. Here, the oncologists responded, made clarification, and explored the subject. It thus seems that oncologists feel more comfortable discussing subjects that are in their field of competence. This facilitates oncologists to deepen the very subject of death but requires patients to adapt to the clinicians’ needs

Identifying patterns allows us to understand communication as an interaction process and not as a simple stimulus–response phenomenon. Patterns make it possible to formulate hypotheses with regard to the different challenges that addressing death pose for the patient and the clinician. Such patterns could also contribute to providing empirical evidence for communication training programs and thus to translate research into the realm of clinical practice.

Regarding research implications, the study illustrates that the analysis of entire consultations provides interesting insights, such as interaction patterns between patients and physicians. Such research approach responds to the call of a recent position paper based on a consensus meeting among oncology communication experts to take the communication context into account (Stiefel et al. Reference Stiefel, Kiss and Salmon2018). Moreover, looking for and identifying patterns is a unique way to grasp clinical communication as it is, a dynamically unfolding process shaped by both, patients and clinicians.

The findings of this study could also provide an impetus to use clinically relevant and contextualized outcome measures when evaluating the impact of the widely implemented communication training programs, which are costly and time-consuming for oncologists (Salmon and Young Reference Salmon and Young2019; Stiefel and Bourquin Reference Stiefel and Bourquin2016). We do not know the underlying reasons why patients and oncologists behaved the way they did when it comes to talking about death. Social sciences and qualitative methods may, however, well complement psychological and communication research to explore underlying motivations. This is another implication of our results for future research.

In terms of the limitations of the study, the results are restricted by the specific setting, public tertiary care centers, the mixed levels of clinical experience of the participating oncology clinicians (chief residents and senior staff members), and the way patients in French-speaking Switzerland adopt the role of patient. Furthermore, we can only formulate hypotheses with regard to the underlying reasons for the observed communication behaviors.

Conclusion

The unease with death persists, despite the increasing willingness of society and medicine to face and address it and the growing importance of communication and communication training in the oncology setting over the years. Having no good answer to patients’ questions does not mean the subject of death should not be addressed, and avoiding it may furthermore increase the feeling of loneliness of patients. As death is an existential issue, addressing other aspects than the biomedical one, such as the spirituality and the impact of the disease and its threat on everyday life, can help the patient feel understood.

Patients and oncologists have multiple ways of raising, pursuing, addressing, and evacuating the subject of death. Being attentive and recognizing these ways and associated interaction patterns can help oncologists to think and elaborate on this topic and to facilitate the discussion, with the main aim to allow patients to express themselves and to hereby allow clinicians to understand a little bit of what they are going through and what kind of interrogations and emotions their patients experience. Oncologists could reflect on their own responses and try to privilege supportive ones, such as exploring what the patient says and trying to understand the underlying reasons of their interrogations with regard to death.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise.