Political values are often considered to be a cornerstone of deliberative democracy. Absent widespread subscription to coherent ideologies (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Kinder and Kalmoe, Reference Kinder and Kalmoe2017), many scholars argue citizens translate their interests into political decisions through the considered application of core values (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Feldman, Reference Feldman2003; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010). Drawing on this theory, Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) hypothesize affective polarization follows from Americans using values to evaluate salient political groups and elites which are polarized in the values they represent (Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015). Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analyze the 1992–1996 American National Election Study (ANES) panel (n = 597) and find value extremity was associated with increased affective polarization toward parties and ideological groups over this period. Further, Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) do not find affective polarization is associated with increased value extremity, which suggests the relationship between values and affective polarization flowed primarily from the former to the latter in the 1990s.

In this note, I reassess the relationship between values and affective polarization using the 2016–2020 ANES panel (n = 2670). Following Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analytic procedures as closely as possible, I seek to understand how the relationships between political values and affective polarization may (or may not) have changed since the 1990s. Using near-identical statistical models, I find value extremity in 2016 is associated with increased affective polarization toward the parties in 2020, but not toward ideological groups or presidential candidates. However, all three measures of affective polarization in 2016 are consistently associated with increased value extremity in 2020. My findings imply the relationship between values and affective polarization flowed primarily from the latter to the former between 2016 and 2020 (cf. Enders and Lupton, Reference Enders and Lupton2021).

This note is structured as follows. I begin by reviewing Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) cross-sectional (1988–2016) and longitudinal (1992–1996) analyses of the relationships between political values and affective polarization in the US. In the second section, I outline an analytic strategy for replicating Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) longitudinal analysis with the 2016–2020 ANES panel. In the third section, I analyze the 2016–2020 ANES and find lagged affective polarization exhibits stronger associations with value extremity than vice versa. In section four, I review possible explanations for why my findings differ from those of Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021), such as changes in the electorate's composition, changes in the political environment related to rising affective polarization and socio-political sorting, and random sampling error. Finally, I conclude by outlining the implications of my findings for thinking about values as influencing, but also being influenced by, affective polarization.

1. Value extremity contributes to affective polarization (1992–1996)

Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) investigate the relationship between political values and affective polarization in the US. Broadly, Enders and Lupton theorize that affective polarization could arise if citizens recognize that different political groups represent distinct values and, in turn, evaluate value-aligned groups more positively than value-misaligned groups. They derive two hypotheses. First, they hypothesize that value extremity—that is, greater distance between an individual's values and political outgroups' values—will be associated with affective polarization. Second, they hypothesize that the associations between value extremity and affective polarization will have strengthened over time as elite-level polarization increases citizens' perceived value distance to political outgroups (Hetherington, Reference Hetherington2009; Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Myers and Thornton2015).

Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) test these hypotheses with ANES Time Series cross-sectional and panel surveys. Their key variables are value extremity and affective polarization. To assess value extremity, Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) use items consistently included on the ANES that tap into respondents' beliefs in egalitarianism (four or six items) and moral traditionalism (four items). They generate a unidimensional scale from these items where egalitarianism and moral traditionalism lie on opposite ends of the values scale.Footnote 1 They then convert the value index into a measure of extremity by “calculating the absolute difference between each respondent's value orientations score and the mean value orientations score for members of the opposite party.” Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) create standard affective polarization measures using differences in 101-point feeling thermometer ratings toward three targets: parties, ideological groups, and presidential candidates. They subtract respondents' ratings of ingroups versus outgroups for each target such that larger values correspond to higher levels of affective polarization.

Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) first assess the associations between value extremity and affective polarization using linear regression on the pooled ANES cross-sections fielded between 1988 and 2016. Their first models separately regress each affective polarization measure on value extremity while controlling for issue extremity,Footnote 2 partisan-ideological sorting (Mason, Reference Mason2018), political interest, education, age, income, religiosity, race/ethnicity, gender, southern residence, and sample-year fixed effects. In subsequent conditional models, they interact value extremity and sample-year to test whether the associations between value extremity and affective polarization have strengthened over time. Their findings are consistent with their hypotheses; value extremity is associated with affective polarization toward parties, ideological groups, and presidential candidates, and these associations strengthened between 1988 and 2016.

Acknowledging that cross-sectional regressions cannot empirically distinguish any potential causal ordering between affective polarization and value extremity, Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) turn to cross-lagged panel modeling (CLPM) in the 1992–1996 ANES panel to assess whether and how value extremity and affective polarization may be related. Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) specify a CLPM for each affective polarization measure. Each CLPM includes two equations estimated via structural equation models and full information maximum likelihood. One equation predicts value extremity in 1996; the other predicts affective polarization in 1996. The independent variables, all measured in 1992, include value extremity, the respective affective polarization measure, and the same controls included in the cross-sectional models (minus sample-year fixed effects). The variables are standardized so CLPM coefficients represent the effects of standard deviation changes in independent variables on the dependent variable (also in standard deviations). To be clear, however, CLPMs suffer from many of the same shortcomings as cross-sectional regression, such as the risk of omitted variables and spurious correlations arising from measurement error. Given the assumptions of CLPMs are usually violated (Lucas, Reference Lucas2023), CLPMs should generally be interpreted as associational estimates.

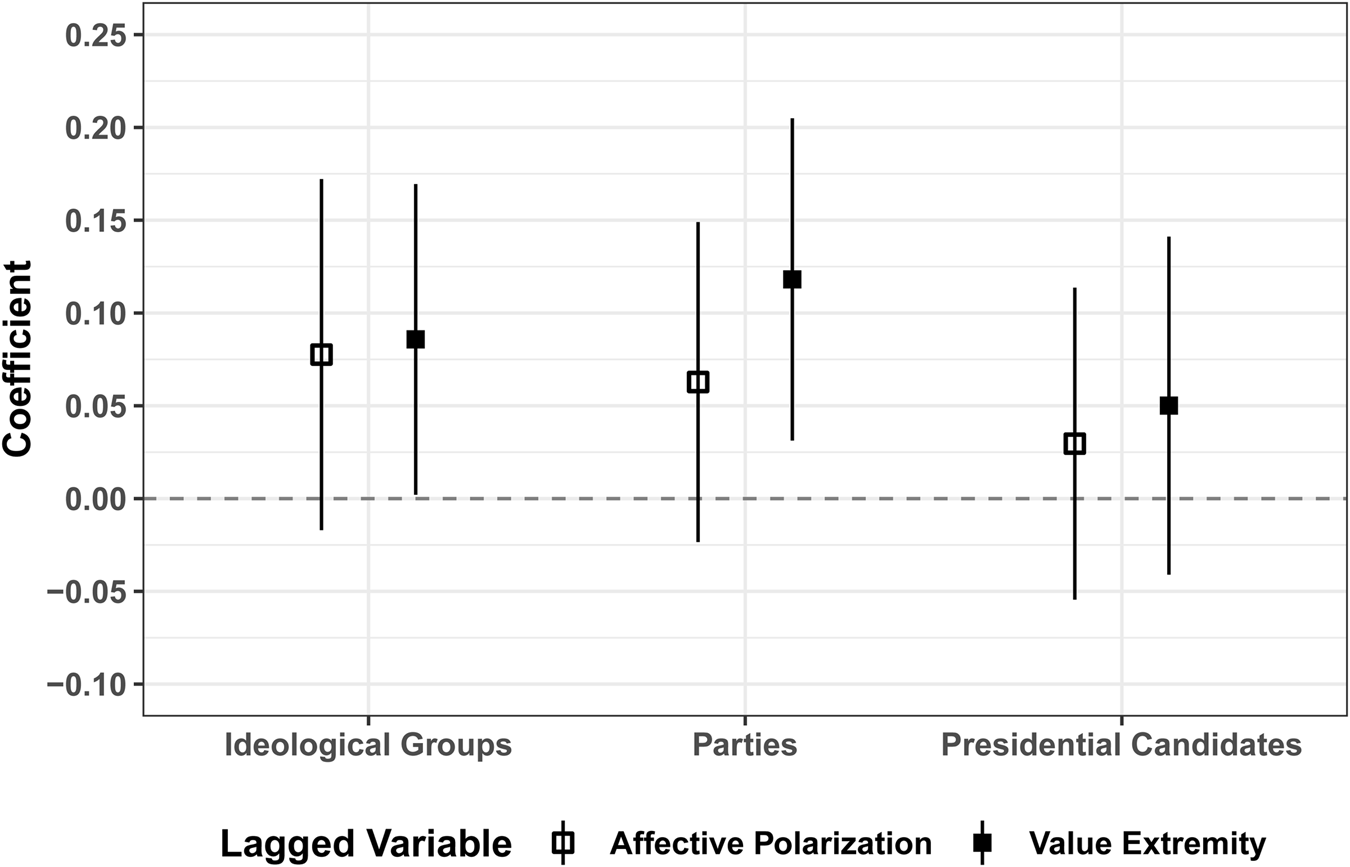

In Figure 1, I reproduce the main results from Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analysis of the 1992–1996 ANES panel.Footnote 3 Consistent with their hypotheses, lagged value extremity is associated with increased affective polarization between 1992 and 1996 in two of three cases. Lagged value extremity is associated with standard deviation increases in affective polarization of 0.086 toward ideological groups (p = 0.045), 0.118 toward parties (p = 0.008), and 0.050 toward presidential candidates (p = 0.281). Notably, lagged affective polarization is not significantly associated with changes in value extremity, which suggests the association between value extremity and affective polarization flows from values to affective polarization during this period. Additionally, although Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) do not report results from models that incorporate sampling weights, their results are robust to weighting for national representativeness (Appendix 5).

Figure 1. Associations between value extremity and affective polarization (1992–1996). Points are standardized coefficients of lagged affective polarization measures on value extremity (white) and lagged value extremity on affective polarization (black) with 95 percent confidence intervals. N = 597.

Source: 1992–1996 ANES panel.

2. Out of sample replication: 2016–2020 ANES panel

At the time of their writing, Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) could only analyze one panel survey that included measures of affective polarization and political values: the 1992–1996 ANES panel. Fortunately, another panel study has since been released with both measures: the 2016–2020 ANES. The 2016–2020 ANES panel includes 2670 respondents who completed through the post-election wave of the 2020 ANES. The total reinterview rate was 73.2 percent.

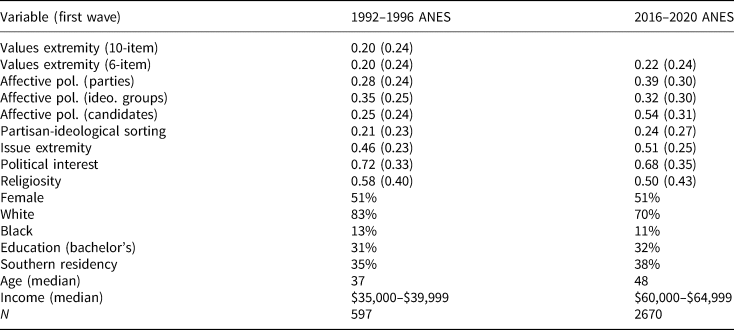

The 2016–2020 ANES panel differs from the 1992–1996 ANES panel in several ways. First, although both panels aim for national representativeness, the composition of the voting-eligible US citizenry has changed since the 1990s. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for each panel in their first wave. Relative to 1992, the electorate in 2016 exhibits slightly more extreme political values and much higher affective polarization toward parties and presidential candidates, though not ideological groups. Partisan-ideological sorting and issue extremity are also slightly more pronounced in 2016. Finally, the 2016 sample is older, less white, and less religious.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics

Table entries are means (standard deviation in parentheses), medians, or percentages. Continuous variables scaled 0–1. All variables derived from the first wave (1992 or 2016). Data weighted. Source: 1992–1996 ANES panel, 2016–2020 ANES panel.

Additionally, the 2016–2020 ANES includes only six of the ten political values items in the 1992–1996 panel: four egalitarianism items and two moral traditionalism items. However, these six items still constitute a unidimensional measure (Appendix 3) with acceptable reliabilities (α 2016 = 0.70, α 2020 = 0.75). Further, in Appendix 6, I replicate Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analysis with an identical six-item value extremity measure and find their conclusions are unchanged. There are otherwise no important differences between variables on the 2016–2020 ANES panel and those on the 1992–1996 ANES panel analyzed by Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021).

Finally, the 2016–2020 ANES panel has a sample approximately 4.5 times larger than that of the 1992–1996 ANES panel. In light of recent work demonstrating that most quantitative political science studies are underpowered (Arel-Bundock et al., Reference Arel-Bundock, Briggs, Doucouliagos, Aviña and Stanley2022), this boost to statistical power is beneficial. Given its large sample and near-identical set of variables to those on the 1992–1996 ANES, the 2016–2020 ANES is well-suited for an out-of-sample replication of Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) longitudinal analyses of the relationships between value extremity and affective polarization.

3. Results: affective polarization contributes to value extremity (2016–2020)

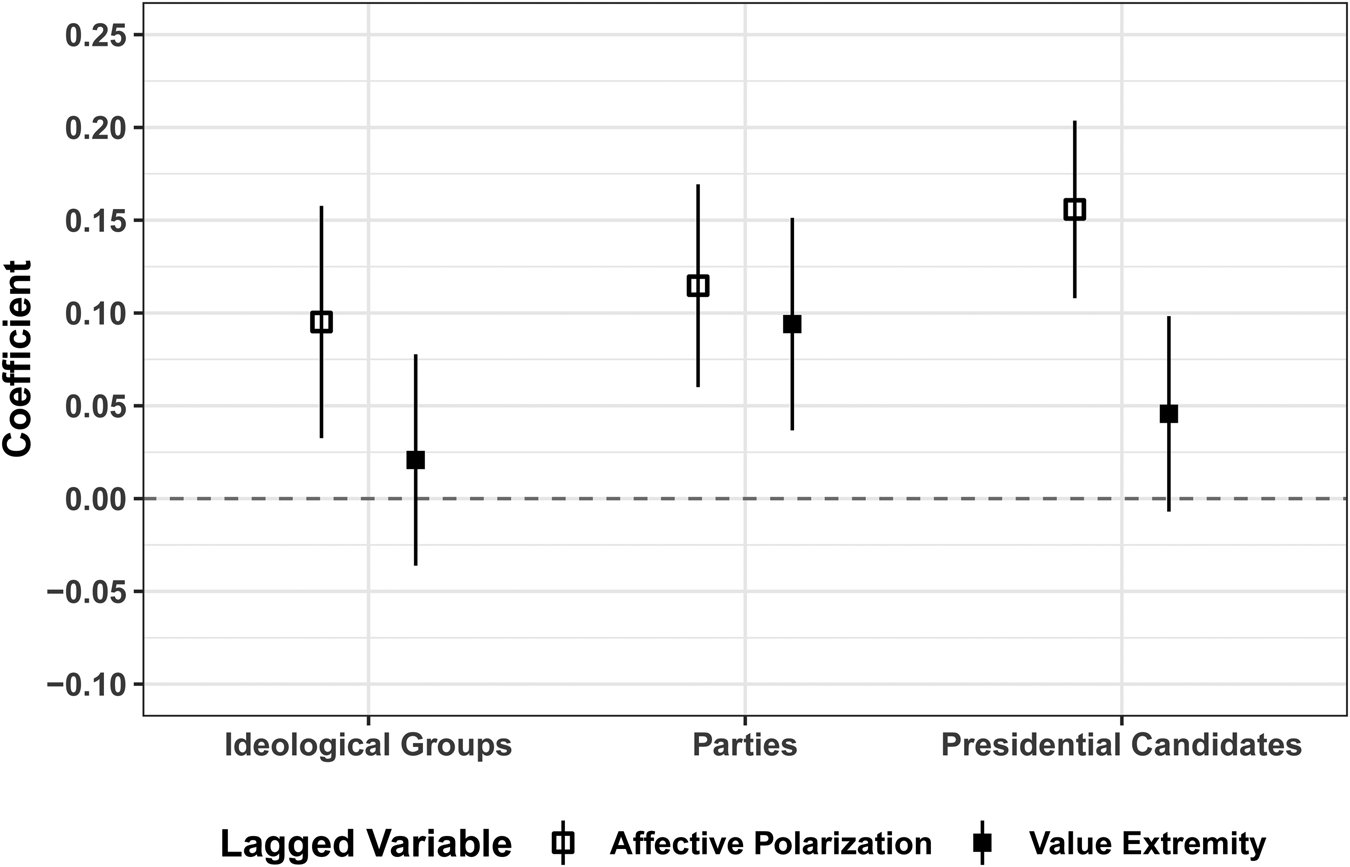

I specify three cross-lagged models to predict value extremity and affective polarization with the 2016–2020 ANES panel. Each model includes two equations simultaneously estimated using full information maximum likelihood. The first equation predicts value extremity in 2020; the second predicts affective polarization in 2020. The independent variables are measured in 2016, and include value extremity, the respective affective polarization measure, issue extremity, partisan-ideological sorting, political interest, education, age, income, gender, religiosity, race/ethnicity, and southern residence.Footnote 4 I employ sampling weights in all analyses, and account for the complex sampling design when deriving standard errors. In Figure 2, I display the key results from the CLPMs.Footnote 5 Note that the coefficients in Figure 2 cannot be directly compared to those in Figure 1 because they are derived from samples with standardized variables of different variances.

Figure 2. Associations between value extremity and affective polarization (2016–2020). Points are standardized coefficients of lagged affective polarization measures on value extremity (white) and lagged value extremity on affective polarization (black) with 95 percent confidence intervals. Data weighted. N = 2670.

Source: 2016–2020 ANES panel.

Looking first at the effects of lagged value extremity on affective polarization, I find lagged value extremity is associated with standard deviation increases in affective polarization of 0.021 toward ideological groups (p = 0.477), 0.094 toward parties (p = 0.002), and 0.046 toward presidential candidates (p = 0.095). I replicate Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) finding that lagged value extremity is associated with affective polarization toward the parties, but not their finding that value extremity contributes to affective polarization toward ideological groups. I similarly find that value extremity is insignificantly related to changes in affective polarization toward presidential candidates. Overall, I find value extremity had limited associations with increases in affective polarization between 2016 and 2020.

The more striking differences between my results and those of Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) emerge when examining the associations between lagged affective polarization and value extremity. Recall that Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) found insignificant associations between affective polarization and value extremity in all three cases. In the 2016–2020 ANES panel, however, all three lagged affective polarization measures are associated with increased value extremity in 2020. Specifically, the estimated effects of lagged affective polarization on value extremity in standard deviations are 0.095 for ideological groups (p = 0.004), 0.115 for party ratings (p < 0.001), and 0.156 for presidential candidate ratings (p < 0.001). Notably, in all three cases, the effects of value extremity on affective polarization are smaller than the effects of affective polarization on value extremity—and significantly so in two of three cases.

4. Discussion

In this paper, I evaluated the relationship between value extremity and affective polarization in the US. I reproduced Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analyses of the 1992–1996 ANES panel, which show that value extremity was associated with affective polarization toward parties and ideological groups, but not presidential candidates, and that affective polarization was unrelated to changes in value extremity. I conducted an out-of-sample replication using near-identical models and the more recent 2016–2020 ANES panel. I found value extremity was associated with affective polarization toward parties, but not ideological groups or presidential candidates. Notably, my findings mostly diverge from Enders and Lupton's when assessing affective polarization's effects on value extremity, where I find all three affective polarization measures were associated with increased value extremity.

There are several differences between my analyses and those of Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) that might explain why our findings differ. First, the composition of the electorate has changed since the 1990s. If the relationships between value extremity and affective polarization are conditioned by compositional variables, these relationships may have changed concomitantly with the electorate. In Appendix 7, I test the possibility that compositional differences explain the differences between my findings and Enders and Lupton's by weighting the 2016–2020 to match the covariate distributions in the 1992–1996 panel using entropy balancing (Hainmueller, Reference Hainmueller2012). I find the associations between lagged affective polarization and changes in value extremity are significant in all three cases, whereas lagged value extremity is insignificantly associated with affective polarization in every case, including toward parties (which originally saw a significant association). This analysis suggests differences in electorates likely do not explain why my findings differ from Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021), though I cannot rule out this explanation entirely since balancing on observables will not necessarily obviate unobserved differences.

Another possible reason why my findings diverge from Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) is that the relationship between affective polarization and value extremity changed since the 1990s. While I do not find most of Enders and Lupton's findings “replicate” in 2016–2020, this does not mean their findings were erroneous. Enders and Lupton's (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) analysis could offer an accurate snapshot of the relationship between values and affective polarization in the 1990s. Affective polarization was lower in this period, and cross-cutting socio-political cleavages were common (Iyengar et al., Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Mason, Reference Mason2018). In this environment, values could have been more central to individuals' political thinking. However, as affective polarization increased during the 21st century and Americans became increasingly well-sorted, values may have become secondary to socio-political ties. If Americans now view values as indicators of group allegiances, affective polarization may be causing Americans to adopt the values of politically similar others (and disassociate from the values of politically dissimilar others). This theory is perhaps especially compelling in light of recent work that finds political identities cause instability in other “core” traits like racial attitudes (Engelhardt, Reference Engelhardt2020), personality (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Lelkes and Malka2021), and even demographic identities (Egan, Reference Egan2020).

Finally, it is worth considering that the differences between my results and those of Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) emerged by chance due to random sampling error. The 1992–1996 ANES panel has 597 respondents; the 2016–2020 ANES panel has 2670. This larger sample may have allowed me to uncover associations between affective polarization and value extremity that existed in the 1990s but could not be identified by Enders and Lupton for a lack of statistical power. Additionally, larger samples reduce the variance in estimated effects due to sampling error, which in turn reduces false-positive findings (Open Science Collaboration, 2015; Loken and Gelman, Reference Loken and Gelman2017; Benjamin et al., Reference Benjamin, Berger, Johannesson, Nosek, Wagenmakers, Berk, Bollen, Brembs, Brown, Camerer, Cesarini, Chambers, Clyde, Cook, De Boeck, Dienes, Dreber, Easwaran, Efferson, Fehr, Fidler, Field, Forster, George, Gonzalez, Goodman, Green, Green, Greenwald, Hadfield, Hedges, Held, Hua Ho, Hoijtink, Hruschka, Imai, Imbens, Ioannidis, Jeon, Jones, Kirchler, Laibson, List, Little, Lupia, Machery, Maxwell, McCarthy, Moore, Morgan, Munafó, Nakagawa, Nyhan, Parker, Pericchi, Perugini, Rouder, Rousseau, Savalei, Schönbrodt, Sellke, Sinclair, Tingley, Van Zandt, Vazire, Watts, Winship, Wolpert, Xie, Young, Zinman and Johnson2018; Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Dreber, Holzmeister, Ho, Huber, Johannesson, Kirchler, Nave, Nosek, Pfeiffer, Altmejd, Buttrick, Chan, Chen, Forsell, Gampa, Heikensten, Hummer, Imai, Isaksson, Manfredi, Rose, Wagenmakers and Wu2018). A reduction in random sampling error could explain why I fail to find significant effects of lagged value extremity on affective polarization in one case (ideological groups) where Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) find significant effects. Given research on replicability in the social sciences, we cannot discount the possibility that different studies, even using near-identical statistical analyses, differ in their findings due to sampling error.

5. Conclusion

A foundational literature in political science contends many citizens make political decisions through a considered application of values. And because values are thought to be stable (Searing et al., Reference Searing, Jacoby and Tyner2019), they can help produce consistent political behaviors among citizens who do not engage in ideological thinking (Zaller, Reference Zaller1992; Feldman, Reference Feldman2003). Indeed, many studies have shown values are associated with political attitudes, identities, and behaviors (e.g., Feldman, Reference Feldman1988; Jacoby, Reference Jacoby2006, Reference Jacoby2014; Schwartz et al., Reference Schwartz, Caprara and Vecchione2010; Goren, Reference Goren2012; Evans and Neundorf, Reference Evans and Neundorf2020; Lupton et al., Reference Lupton, Smallpage and Enders2020; Ciuk Reference Ciuk2022; Ollerenshaw and Johnston, Reference Ollerenshaw and Johnston2022). Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) extend this values literature, concluding that affective polarization between 1992 and 1996 increased as Americans made reasonable judgements about the values represented by parties, ideological groups, and presidential candidates.

Looking at recent panel data from 2016 to 2020, however, I find that affective polarization is the stronger, more consistent predictor of value extremity than vice versa. My findings thus invoke more pessimistic conclusions than those reached by Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021) about values and the prospects for deliberative democracy. Amidst rising affective polarization and political sectarianism, values may serve more as endogenous, expressive signals of socio-political identity than deep-seated dispositions which independently drive political behavior. This conclusion is perhaps not particularly surprising in light of research that finds values are less stable than partisanship (Goren, Reference Goren2005); that values are associated with particular parties by Americans (Connors, Reference Connors2023); and that social influences, party cues, and campaigns shape value expression (McCann, Reference McCann1997; Goren et al., Reference Goren, Federico and Kittilson2009; Connors, Reference Connors2020).

My analysis supports a revisionist account of values, one where values are not exogenous to socio-political influences. However, these conclusions should be tempered by the limitations of this study's design. Cross-lagged panel models require untenably strong assumptions to be interpreted as causal effects; my findings, like those of Enders and Lupton (Reference Enders and Lupton2021), should therefore be viewed as associational. Current data limitations preclude applying stronger designs for inference, such as the random-intercept CLPM, which requires three waves (Lucas, Reference Lucas2023). Usefully, however, the ANES plans to reinterview 2016–2020 panelists in 2024. In the spirit of the present study, when 2024 data become available, a replication using random-intercept CLPMs to identify what causal relationships exist between values and affective polarization seems an obvious avenue for future research.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2023.34. To obtain replication material for this article, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EJDTXJ

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Christopher D. Johnston, D. Sunshine Hillygus, Daniel Stegmueller, participants of the 2023 Institute for Humane Studies Junior Fellowship program, two anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Political Science Research and Methods for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript. The author also thanks Adam M. Enders and Robert N. Lupton for their comments on the manuscript, and for making available their reproduction files, which served as a template for this manuscript's empirical analysis.

Competing interest

None.