Impact statement

Our scoping review of participatory and user-led research in mental health in Brazil highlights the importance of engaging the community of interest in the research process and challenges the traditional view of people with psychiatric diagnoses as mere research objects. Our findings reveal that participatory research in mental health in Brazil is not treated as separate from participation in shaping mental health policy, driving care, or the broader right to fully participate in societal life and enjoy social and civil rights. We identified several obstacles to full participation, including the biomedical model, primacy of academic and scientific knowledge, and systemic barriers. By foregrounding local epistemologies and promoting Global South leadership in mental health research, our work contributes to the global debate about participation and mental health research. Our findings have implications for mental health research in Brazil and beyond, and we anticipate that our research will be used to inform the development of more inclusive and equitable research practices in mental health worldwide.

Introduction

Participatory research denotes the engagement and meaningful involvement of the community of interest in multiple stages of investigation, from design to data collection, analysis, and publication. In the 1970s, participatory action research (PAR), influenced by the work of Brazilian author Freire (Reference Freire1987), emerged in the social sciences to challenge the neutrality of science and address power asymmetries between academic and popular knowledge (Borda, Reference Borda2008). PAR proposes a North–South encounter based on solidarity and mutual enrichment paying special attention to the colonial legacy of oppressed countries. According to de Sousa Santos (Reference de Sousa Santos2015), an understanding of the world beyond the western understanding of the world exists; we need cognitive justice to have global social justice; and emancipation takes shape in diverse ways outside of Western theory (de Sousa Santos, Reference de Sousa Santos2015). As such, this type of research favors subject to subject interactions toward transformation, rather than subject to object, thus reshaping epistemological notions that underpin traditional research (Fals-Borda, Reference Fals-Borda1987). Mental health research in the Global North incorporated principles of PAR to study problems with communities (Kidd et al., Reference Kidd, Davidson, Frederick and Kral2018), and a discrete body of knowledge led by people who identified as consumers, survivors, and ex-patients of psychiatry has developed (e.g., survivor research and mad studies) (Faulkner, Reference Faulkner2017). The Alma Ata was the first international declaration to explicitly state that individuals have the right to participate in shaping healthcare (WHO, 1978). Since the 1980s, public and patient involvement (PPI) or community and public engagement, grown out of civil rights movements, governmental initiatives, and disability rights movements (Tomes, Reference Tomes2006; Sweeney et al., Reference Sweeney, Beresford, Faulkner, Nettle and Rose2009), further consolidated the importance of participation in shaping public policy and in research (Hickey et al., Reference Hickey, Porter, Tembo, Rennard, Tholanah, Beresford, Chandler, Chimbari, Coldham, Dikomitis, Dziro, Ekiikina, Khattak, Montenegro, Mumba, Musesengwa, Nelson, Nhunzvi, Ramirez and Staniszewska2022). This tradition continued to expand in high-income countries (HICs), and acceptance of the principles of participatory research by mainstream science is growing (Pearce, Reference Pearce2021). Examples of the institutionalization of PPI in HICs are the National Institute of Health Research funded INVOLVE in the United Kingdom (started in 1996), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) in the United States, and the 2009 International Collaboration for Participatory Health Research with all but one steering committee member coming from the Global North (Beresford and Russo, Reference Beresford, Russo, North, Nolte, Merkur and Anell2020).

Participatory research in mental health counters the history of a field defined by the politics of exclusion (Mills, Reference Mills2014). Unlike other medical specialties, psychiatry’s relationship to social order has shaped discourses (e.g., notions of the degenerative course of mental illness, mental illness as a moral problem, and mental illness as deficit), and interventions (e.g., long-term internment and involuntary hospitalizations) that resulted in the systematic exclusion of individuals from society (Foucault, Reference Foucault1999). While a shift from asylums as the privileged locus of “treatment” happened globally, and deinstitutionalization became a priority, the issue of social exclusion has not been resolved, and even as co-production and participation develop in research, power asymmetries remain (Rose and Kalathil, Reference Rose and Kalathil2019). Research participation in low- and middle-income countries is further complicated by the enduring history of colonial legacies (Bulhan, Reference Bulhan2015) and the geopolitics of knowledge (Naidu, Reference Naidu2021) that privileges Euro-American epistemologies (Mignolo, Reference Mignolo2005), which materializes in science in multiple ways. These have multiple consequences: globally, more than 98% of all funding streams for mental health are awarded by HICs (Woelbert et al., Reference Woelbert, White, Lundell-Smith, Grant and Kemmer2020) who consequently occupy a privileged position with respect to knowledge production (Abimbola, Reference Abimbola2019); representation of individuals who are white, male, and HIC-based working at academic places of power (e.g., editorial boards and universities) is disproportionate (Naidu, Reference Naidu2021). In addition, interventions developed in the Global North have been systematically adapted and implemented in the Global South, for example, the World Health Organization’s mhGAP (Timimi, Reference Timimi2011). An equally consequential form of power and exclusion lies in the epistemological dominance of HICs, who determine the methods and knowledge that count, and continue to exclude, silence, and oppress forms of being and knowing originating in the Global South (Alejandro Leal, Reference Alejandro Leal2007; Bulhan, Reference Bulhan2015; Bhakuni and Abimbola, Reference Bhakuni and Abimbola2021; Naidu, Reference Naidu2021). Psychiatry’s history of exclusion and marginalization combined with the epistemic violence that results from the geopolitics of knowledge that shape the North–South relationship places participatory research in mental health in the Global South at the intersection of multiple oppressions.

The psychiatric reform movement in Brazil took place in the context of broader societal changes toward democratization. Starting in the 1970s, mental health workers in the country organized to denounce the abuse and inefficiency of psychiatric hospitals to treat and support the recovery of people with severe mental health problems (Amarante, Reference Amarante1998). Inspired by Basaglia’s Democratic Psychiatry and the experiences of deinstitutionalization in Italy, the anti-asylum movement grew side by side with Brazil’s universal public health system, both informed by a strong critique of positivist and biomedical epistemologies as insufficient to address social problems (Yasui, Reference Yasui2010; Amarante, Reference Amarante2015). This paradigmatic shift from asylums to the psychosocial care system was enshrined in law in 2001 (Law 10.216). Service user participation is a key feature of the Brazilian public health system and built into the principles of the psychiatric reform movement as well as the public healthcare system. Despite numerous successful experiences of service user involvement and leadership in mental health policymaking, service delivery, and advocacy (Vasconcelos, Reference Vasconcelos2009), effective and consistent participation remains aspirational.

Participation in research, however, is not as well established. More than 20 years since the shift in how mental health services are organized in Brazil has been enshrined in law, evaluation of mental health services using participatory methods remains scarce (Ricci et al., Reference Ricci, Pereira, Erazo, Onocko-Campo and Leal2020). This historical context makes it so that participation in policymaking, advocacy, and research are not understood separately. The state of the art of mental health research in the country is unknown. This knowledge gap is problematic locally and globally. Locally, participatory initiatives remain isolated in the context of specific projects and a national agenda for the advancement of participation of service users and people with lived experience of mental health problems would benefit from this scientific knowledge base. Globally, researchers remain unaware of the wealth of knowledge produced in Brazil. Thus, our study sought to review the empirical participatory literature in mental health in Brazil, identify common themes, and synthesize the results.

Objective

Our scoping review’s objective was to chart and analyze the empirical participatory mental health research literature in Brazil. Our review focused on research studies and included gray literature. Specific objectives were to describe how participation is conceptualized in mental health research in Brazil, to identify key concepts associated with participatory research, and to identify the main obstacles to participatory research in mental health in the country.

Methods

Our team included academics in Brazil, Chile, the United States, and the United Kingdom, and people with lived experience of mental health challenges. Our review followed the Joanna Briggs Institutes’ guidelines (Peters et al., Reference Peters, Godfrey, McInerney, Baldini Soares, Khalil and Parker2017) and PRISMA extension guidelines for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Reference Tricco, Lillie, Zarin, O’Brien, Colquhoun, Levac, Moher, Peters, Horsley, Weeks, Hempel, Akl, Chang, McGowan, Stewart, Hartling, Aldcroft, Wilson, Garritty, Lewin, Godfrey, Macdonald, Langlois, Soares-Weiser, Moriarty, Clifford, Tunçalp and Straus2018).

Eligibility criteria

Eligibility included studies that used participatory research methods, broadly defined as research in which service users’ and family members’ roles in the study went beyond those of research subjects (i.e., an individual who provides information or data to help answer a research question). We defined participatory research procedures broadly and included studies that employed member-checking, consultations, co-production, data validation procedures, and stakeholder consultation groups. We included empirical studies conducted in Brazil and published in peer-reviewed journals in Portuguese, Spanish, English, or French (study team’s languages). We included the gray literature as well. We did not specify dates. Studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods were eligible. Studies that included participants of any age, sex, gender, ethnicity, race, or class were included. Studies involved service users and/or family members with any mental health diagnosis but excluded those with a primary diagnosis of a physical health problem (e.g., epilepsy and dementia) or substance use exclusively. We excluded studies that claimed to be participatory but provided no evidence of participation in the methods or results section of the paper. We excluded studies focusing on providers only but kept those that included providers if families or service users were included as well.

Information sources

Our initial exploration of the topic revealed a series of challenges to traditional search strategies. Key words and vocabulary were inconsistent, metadata were missing, and titles were not available in databases (e.g., Web of Science and Scopus). To address these challenges, our team developed a multipronged strategy that combined bidirectional citation tracking (Hinde and Spackman, Reference Hinde and Spackman2015) and a targeted search strategy to a variety of databases to identify relevant studies. We conducted two bidirectional searches and one additional search of targeted databases.

The research team, through their knowledge about this literature, Google Scholar searches, and consultations with experts, first identified 10 relevant studies (known as “pearls”), and the medical librarian used these pearls to identify articles through a systematic search of their cited and citing articles using citationchaser, SciELO, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

Using the included studies, we identified relevant terms using the Systematic Review Accelerator WordFreq tool (Clark et al., Reference Clark, Glasziou, Del Mar, Bannach-Brown, Stehlik and Scott2020) and developed a targeted search strategy. The librarian searched the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycInfo, Global Health, LILACS, Web of Science, Scopus, SciELO, BDTD, and the PBiPortal de BuscaIntegrada. We limited search results to English and Portuguese titles because the previous step did not yield relevant results in French and Spanish.

Our team translated the search strategy to Portuguese between the following databases to find published and unpublished (i.e., gray) literature: PubMed, MEDLINE (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycInfo (Ovid), Web of Science Core Collection, Scopus, and Scielo.br. We pooled results in EndNote, removed duplicates, and uploaded to Covidence. We identified relevant theses and dissertations using the National Thesis Database BDTD and relevant books using the Universidade de São Paulo library catalog. Finally, our team consulted experts in the field, charted the main publication venues outside mainstream academic databases (ABRASME, APRAPSO, and ABRASCO for conference proceedings), and hand-searched key journals (e.g., Revista de Saúde Coletiva).

Selection of sources of evidence

Two independent reviewers screened studies’ titles, abstracts, and full texts using screening checklists that were pilot-tested and adjusted using the first 100 articles. Decision trees helped resolve ambiguous situations during the screening process. Ultimately, the study team decided to exclude the gray literature because most did not present primary studies. Many studies did not describe the methods making it difficult to assess if they were primary studies or not. Relevant theses and dissertations that were empirical research generally had an associated peer-reviewed publication, which we included.

Data charting process

Our team iteratively developed a data charting form using Covidence and Excel and used it to extract relevant information (Tables 1 and 2). The first author and a member of the study team extracted the data independently and resolved conflicts together. We consulted a third member of the study team when consensus could not be reached.

Table 1. Demographic, clinical, and methodological characteristics of the included studies

Table 2. Participation definition, operationalization, co-authorship

Data items and synthesis of results

Synthesis of results was iterative. We extracted data items that were relevant to the objectives of our review first in Covidence and then in Excel, including: article information (i.e., title, authors, year of publication, and aims); demographic information (i.e., age, sex, gender, ethnicity, race, and socioeconomic status); clinical characteristics (i.e., mental health problems) of the sample; whether participants were service users, family members, or providers; the study setting (i.e., community mental health center, primary care, and university); the methodological and analytical approaches; and definitions of the participatory elements in the study (e.g., member checking, designing research questions, and co-production). We used Atlas.ti to free-code the articles, and finally inductively developed a set of categories by grouping and organizing the codes.

Results

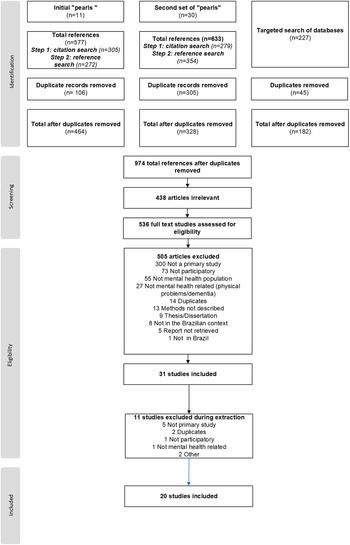

We identified 1,437 references through the search strategy. After removing 814 duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 974 references. We assessed 536 full text studies for eligibility and excluded 516 for several reasons (Figure 1), leaving final pool of 20 studies to be charted and synthesized.

Figure 1. Screening and selection of articles.

Characteristics of sources of evidence

Study publication dates ranged from 2009 to 2021. Most studies were carried out in the South and Southeast areas of Brazil (N = 13) and published in Portuguese (N = 19). Sample sizes ranged from 7 to 420, with a median number of 15 participants. Most studies were conducted at Community Mental Health Centers (N = 14) and employed qualitative methods (N = 18). Studies used a variety of data analysis approaches, with hermeneutic analysis (N = 7) being the most common. Most studies included participants diagnosed with serious mental illness, psychosis, or both (N = 18). None of the studies reported full demographic characteristics (i.e., sex, age, and race/ethnicity).

Nine studies reported on a multicentric study in partnership with a Canadian university that translated and implemented a medication management guide in community mental health centers in several regions of Brazil (Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, de Lima Palombini, Silva, Passos, Leal, Serpa, de Castro e Marques, Gonçalves, dos Santos, de Lima e Silva Surjus, Arantes, Emerich, de Carvalho Otanari and Stefanello2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Silveira et al., Reference Silveira, de Lima Palombini and Moraes2014; Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017; Chassot and da Silva, Reference Chassot and da Silva2018; Senna and Azambuja, Reference Senna and Azambuja2019; Palombini et al., Reference Palombini, Oliveira, Rombaldi, Pasini, Ferrer, Azambuja and Saldanha2020; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Renault, de Sá Mello and Guerini2020). Seven studies reported using principles of Guba and Licoln’s fourth-generation evaluation, a constructivist method – focused on negotiation – that engages stakeholder groups across all phases in iterative processes to reach consensus (Guba and Lincoln, Reference Guba and Lincoln1989, Reference Guba and Lincoln2001; Kantorski et al., Reference Kantorski, da Rosa Jardim, Wetzel, Olschowsky, Schneider, Resmini, Heck, de Lourdes Machado Bielemann, Schwartz, VCC, Lange and de Sousa2009; Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, Furtado, Miranda, Ferrer, Passos and Gama2009; Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Moreira and Onocko-Campos, Reference Moreira and Onocko-Campos2017; Alves et al., Reference Alves, Kantorski, Andrade, Coimbra, Oliveira and Silveira2018; Palombini et al., Reference Palombini, Oliveira, Rombaldi, Pasini, Ferrer, Azambuja and Saldanha2020).

Group validation of results was the most common participation strategy (Kantorski et al., Reference Kantorski, da Rosa Jardim, Wetzel, Olschowsky, Schneider, Resmini, Heck, de Lourdes Machado Bielemann, Schwartz, VCC, Lange and de Sousa2009; Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, Furtado, Miranda, Ferrer, Passos and Gama2009; Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017; Alves et al., Reference Alves, Kantorski, Andrade, Coimbra, Oliveira and Silveira2018; Massa and Moreira, Reference Massa and Moreira2019; Palmeira et al., Reference Palmeira, Leão, Neto, Barreto, de Cassia Ribeiro, Keusen and Cavalcanti2021). Only two studies explicitly stated that participants were involved in all stages of research (Chassot and da Silva, Reference Chassot and da Silva2018; Vaz et al., Reference Vaz, Lyra, Cardoso, Silva and Moraes2019). Participants were not co-authors in any of the included studies, nor was there mention of authors’ lived experience in any of the studies we included. Descriptions of the value and role of participation in research varied. Authors acknowledged the importance of community participation in public policy as a means to connect research and action (Lima et al., Reference Lima, Couto, Delgado and de Oliveira2014), noting that participation in research addresses power imbalances in the researcher–subject dyad (Passos et al., Reference Passos, Renault, de Sá Mello and Guerini2020). Another study marked diversity, respect and differences, and acknowledgment of lived experiences as legitimate sources of expertise as important reasons for participation (Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, Furtado, Miranda, Ferrer, Passos and Gama2009). One study described participation as a tool to increase political reflection, bring attention to the rights participants may have lost, and increase the relevance of research (Moreira, Reference Moreira2021). Studies that employed fourth-generation evaluation methods highlighted the importance of stakeholder involvement in all stages of research to level power asymmetries in research and increase the relevance of knowledge produced (Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Alves et al., Reference Alves, Kantorski, Andrade, Coimbra, Oliveira and Silveira2018; Senna and Azambuja, Reference Senna and Azambuja2019; Palombini et al., Reference Palombini, Oliveira, Rombaldi, Pasini, Ferrer, Azambuja and Saldanha2020). One example of fourth-generation evaluation included service users, managers, psychiatry residents, and family members to translate, adapt, and test a medication management tool for people with serious mental illness. Their inclusion fostered a sense of agency in the research process, and researchers see themselves as social actors sharing the experience of the world and bringing their own subjective experiences (Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014). One study noted the need to increase participation in research, especially in mental health, given that, historically, service users have been excluded from decision spaces including about their own treatment (Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017). One study noted that definitions and operationalization of participation vary greatly and can have different meanings (Moreira and Onocko-Campos, Reference Moreira and Onocko-Campos2017).

Synthesis of results

Importance of participation

In the context of the Brazilian psychiatric reform movement, several studies have considered participation from various dimensions: policy, political, and clinical. From a policy perspective, studies note the shift from the biomedical, hospital-centric model of care to the creation of community-based mental health centers (CAPS) as the main locus of treatment in the public mental health system (Serpa Junior et al., Reference Serpa Junior, Campos, Malajovich, Pitta, Diaz, Dahl and Leal2014). From a political standpoint, participation in research and in shaping services emblematizes autonomy, citizenship, and the general exercise of civil liberties. Finally, the clinical perspective, more directly related to treatment encounters and service delivery, amplifies the political by connecting suffering with exclusion and marginalization; and treatment with freedom, autonomy, and participation in society.

It [action research] is an essentially political way of doing research, which aims at the promotion of citizenship and focuses on the processes of social exclusion. (Moreira and Onocko-Campos, Reference Moreira and Onocko-Campos2017, p. 465)

Power and knowledge

A prevailing theme among selected articles is that psychiatry has historically oppressed and silenced the people it aims to serve by placing excessive emphasis on scientific and professional knowledge, and by reducing individuals to their diagnoses and symptoms (Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017; Moreira, Reference Moreira2021).

Deemed incapable of living in society, subjects are silenced and their tragic experience, frustration, failure and everyday suffering are gradually removed from daily experience and turned into psychopathological categories. (Moreira, Reference Moreira2021, p. 1190, our translation)

Studies point to harmful diagnostic language and treatment practices, rooted in a reductionist biomedical model, that have harmed and violated the rights of people with mental health problems.

The separation between knowledge and the experience of madness legitimized Psychiatry’s knowledge supremacy and made interventions also an expression of a power-knowledge in the name of treatment. (Moreira, Reference Moreira2021, p. 1190, our translation)

Authors suggest a need to correct power imbalances as critical to advance mental healthcare. These perspectives are strongly rooted in the works of Foucault and Basaglia.

Autonomy and empowerment

Empowerment has historical roots in the struggle for civil rights in Brazil starting in the 1970s. Grounded in the work of Freire (Reference Freire1987) and popular education, this tradition motivated the public health and mental health reform movements to transform traditional forms of power and knowledge and foreground the rights of the historically oppressed (Garcia et al., Reference Garcia, da Silva Lira, Severo, de Melo Arraes Amorim and da Silva2017). In mental health, authors note that empowerment can be paradoxical because the need for special social rights (e.g., benefits, protected work, and free transportation) often clashes with universalist claims of civil rights (e.g., equal rights, social inclusion, and full participation in society) due to the extreme disenfranchisement of populations with intersecting vulnerabilities (e.g., extreme poverty, psychiatric diagnosis, violence, and food insecurity) (Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017).

In a country in which the precarity of access to social rights for survival is constant, the service user in intense psychic suffering seems to, often, experience a double process of exclusion: to be Brazilian and to be mad. (Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014, p. 686, our translation)

In clinical care, lack of empowerment means not having enough information to make decisions about treatment. This is reinforced by power imbalances favoring professional and academic knowledge (Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, de Lima Palombini, Silva, Passos, Leal, Serpa, de Castro e Marques, Gonçalves, dos Santos, de Lima e Silva Surjus, Arantes, Emerich, de Carvalho Otanari and Stefanello2012). Increasing autonomy is an important treatment outcome in the selected studies (Kantorski et al., Reference Kantorski, da Rosa Jardim, Wetzel, Olschowsky, Schneider, Resmini, Heck, de Lourdes Machado Bielemann, Schwartz, VCC, Lange and de Sousa2009; Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, Furtado, Miranda, Ferrer, Passos and Gama2009; Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Lima et al., Reference Lima, Couto, Delgado and de Oliveira2014; Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017; Alves et al., Reference Alves, Kantorski, Andrade, Coimbra, Oliveira and Silveira2018; Chassot and da Silva, Reference Chassot and da Silva2018; Senna and Azambuja, Reference Senna and Azambuja2019; Palombini et al., Reference Palombini, Oliveira, Rombaldi, Pasini, Ferrer, Azambuja and Saldanha2020; Passos et al., Reference Passos, Renault, de Sá Mello and Guerini2020; Moreira, Reference Moreira2021; Palmeira et al., Reference Palmeira, Leão, Neto, Barreto, de Cassia Ribeiro, Keusen and Cavalcanti2021).

Historically, the Psychiatric Reform movement posed the redefinition of the meaning of autonomy for community based mental health service users as a clinical-political challenge. This meaning of autonomy must broaden and even shift the meaning inaugurated by modernity, because autonomy is no longer conceived as strictly individual. In the Brazilian Psychiatric Reform movement, the process of becoming autonomous and of emancipation is considered collective and shared. (Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017, p. 1545, our translation)

Obstacles to full participation

Participation in research, treatment, and societal life were intertwined in most studies and not analyzed separately. Key obstacles to full participation were conceptions of mental health (Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Serpa Junior et al., Reference Serpa Junior, Campos, Malajovich, Pitta, Diaz, Dahl and Leal2014) (e.g., the biomedical model and psychopathology); systemic issues (Emerich et al., Reference Emerich, Campos and Passos2014; Palmeira et al., Reference Palmeira, Leão, Neto, Barreto, de Cassia Ribeiro, Keusen and Cavalcanti2021) (e.g., tutelage, violence, poverty, and lack of access to healthcare and basic rights); power asymmetries (Onocko Campos et al., Reference Onocko Campos, de Lima Palombini, Silva, Passos, Leal, Serpa, de Castro e Marques, Gonçalves, dos Santos, de Lima e Silva Surjus, Arantes, Emerich, de Carvalho Otanari and Stefanello2012; Gonçalves and Campos, Reference Gonçalves and Campos2017; Moreira and Onocko-Campos, Reference Moreira and Onocko-Campos2017) (e.g., primacy of academic and professional knowledge, infantilizing service users, and disenfranchisement in treatment).

Consequently, the team’s actions often are directed to the need for symptomatic remission, and their service users’ words remain muted due to the consideration given to their symptoms. This suggests that the responses indicated by the teams are still supported by the medical-biological perspective of understanding the phenomena of mental suffering, which does not seem to match what should be the object of work in this new context: the existence-distress in relation with the social. (Moreira and Onocko-Campos, Reference Moreira and Onocko-Campos2017, p. 471)

Discussion

The overarching aim of this review was to chart and synthesize the participatory research in mental health in Brazil. We identified 20 relevant studies. Studies stressed the importance of participation in research as part of a broader democratizing process, reshaping power and knowledge relationships between expert and experiential knowledge. Studies noted that empowerment and autonomy are at the center of the Brazilian Psychiatric Reform movement and that participatory research lends itself to support this emancipatory project. Included studies highlighted that Brazilian mental health service users endure intersecting and synergistic processes of social exclusion that must be acknowledged. The biomedical model’s reductionist views of mental health, violence, poverty, and social exclusion were all identified as barriers to full participation in research and in shaping public policy.

Overall, Brazilian researchers did not define participatory research as distinct from other important participatory processes in society, including mental health service evaluation, public policy, advocacy, and broader claims of rights and liberties citizens must be entitled to. By refusing to treat these domains separately, Brazilian researchers have emphasized service evaluation and qualitative research in lieu of efficacy and effectiveness trials to establish the evidence base of specific interventions. This may be the result of the historical partnership of mental health professionals who consider themselves militants and advocates for the rights of service users. This configuration is not as common in the Global North, which tends to place service users and providers on opposite political sides with conflicting interests.

Brazilian participatory research has been gradually developing in the country, and included studies highlighted the importance of participation; however, most studies only included participants in member checking activities. Claims of full participation were not substantiated or well described, and authorship was limited to researchers, even when there were claims of a participatory writing process. None of the studies reported full demographic information (age, sex/gender, and race/ethnicity), suggesting that reporting practices are inconsistent throughout and are not specific to participation. Participation is further complicated by multiple vulnerabilities mental health service users experience in Brazil, including poverty, limited literacy, and social exclusion. The tension between special and universal rights, a perhaps false tension if we consider the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) and a rights-based approach to mental health (Pūras, Reference Pūras2017), featured in included studies. The emphasis of this literature on the concepts of autonomy and empowerment challenges the paternalistic nature of special benefits as they often rely on specific diagnoses and imply a deficit, perpetuating the narrow biomedical and individual-centered understanding of disabilities. On the other hand, special rights have historically played an important role in overcoming past and ongoing oppression and exclusion of this population promoting social justice.

We note that nearly half of the included studies were conducted in partnership with a Global North country, suggesting that native participatory experiences not mediated by HICs are even rarer. The existence of well-developed theories of participatory research in Brazil using local epistemologies suggests that the scarcity of this type of research may be more related to funding inequities than a deficit in the field.

Since 1988, participation in public policy development and broader political participation in Brazil has been expanding, especially in public health. In mental health, participatory service evaluation is one of the most developed areas in which participation has been more fully implemented (Ricci et al., Reference Ricci, Pereira, Erazo, Onocko-Campo and Leal2020); nevertheless, projects still fail to center service users and often only include other stakeholders (Furtado et al., Reference Furtado, Onocko-Campos, Moreira and Trapé2013) (e.g., policymakers, administrators, providers, and leadership). Compared to HICs, Brazil still lags in this area. This must be understood within the broader landscape of global mental health funding inequities and consider that 98% of all mental health research funding comes from HICs (Woelbert et al., Reference Woelbert, White, Lundell-Smith, Grant and Kemmer2020). A systematic review of the literature shows that mental health research in Brazil places a bigger focus on providers and work processes rather than outcomes and service users’ perspectives (de Rosalmeida Dantas and Raimundo Oda, Reference de Rosalmeida Dantas and Raimundo Oda2014). Although the Psychiatric Reform movement has promoted a shift in the traditional psychiatric paradigm, the biomedical model of psychiatry is still pervasive in community-based mental health services (Jorge et al., Reference Jorge, Campos, Pinto and Vasconcelos2012; Serpa Junior et al., Reference Serpa Junior, Campos, Malajovich, Pitta, Diaz, Dahl and Leal2014); thus, power asymmetries in care continue, further supporting the need for increased participation. Influences from HICs appear in how participation is understood and practiced in mental health research in Brazil (notably in the use of fourth-generation evaluation methods); however, it is safe to say that the history of the Sanitary and Psychiatric reform movements in the country and the local scholarly traditions shaped a well-defined autochthonous field. Participation in Brazil does not fit neatly into conceptual definitions from the Global North, such as user-led (Rose, Reference Rose2003) and co-creation (Greenhalgh et al., Reference Greenhalgh, Jackson, Shaw and Janamian2016); instead, Brazilian authors stress that participation has multiple meanings and applications. Importantly, participation is strongly rooted in what Brazilian authors call collective autonomy and in the rights of those who face multiple vulnerabilities and social exclusion (Passos et al., Reference Passos, de Carvalho Otanari, Emerich and Guerini2013). While tensions between research and activism are common (Montenegro, Reference Montenegro2018), the neat separation of interests between providers and service users is not relevant in the Brazilian context, and partnerships across stakeholders are fundamental.

It is noteworthy that 9 out of the 20 selected studies reported on a partnership with a Canadian university. Globally, mental health funding is unevenly distributed with HICs setting the agenda for the rest of the world. Along with setting the agenda, partnerships between the Global North and Global South in research are likely to be asymmetric despite good intentions. The project that yielded almost half of the publications we report here involved the translation and adaptation of a Canadian instrument, and not the creation of a native instrument. Such partnerships rarely ensure sustainability, and the impact of such projects tends to be limited to the life of the grant. Our study team has had multiple experiences with progressive researchers from the Global North who refuse to acknowledge a partnership between mental health providers and service users is possible. By setting the terms of what participation means, and what counts and does not, the Global North effectively continues to erase our history and deny our entrance in the debate unless we do so from a place of need and helplessness.

Limitations

Our study had limitations. Our group had to build creative strategies to overcome challenges related to missing metadata and unorthodox scientific reporting practices. The definitions of empirical research do not fully map out to how research is conducted in Brazil, making it difficult to extract data using traditional methods. Our team excluded theses and numerous articles because it was not clear if they were empirical studies or not, even though some presented data. Studies using cartographic methods were largely excluded, though many claimed to be participatory. While reviews of the scientific literature are important, they fail to include other forms of knowledge production and participation. This is particularly true for the Global South and relates to the inequities mentioned in our discussion.

Conclusions

Our study reveals important knowledge gaps. Participatory procedures were generally not well described except for the narrative data validation focus groups which are clearly conceptualized and form a discrete body of literature with well-described methods and procedures. During the screening process, this became evident to our group, and we were forced to exclude potentially relevant articles because methods were not well described or were not described at all. Given the importance of participation in mental health research, the field could benefit from more standardized ways of reporting participatory procedures, which would in turn create better accountability of what counts as meaningful participation. We must acknowledge that the scientific literature does not fully capture the wealth of knowledge production and participation in the country. New and creative methods to synthesize the scientific and non-scientific (e.g., artistic) knowledge base produced by mental health service users are needed.

Among the numerous obstacles to participation, disenfranchisement, poverty, and lack of access to social and civil rights are particularly relevant. The intersecting vulnerabilities of being Brazilian and diagnosed with mental illness substantively impact participation in research and beyond. Service users who rely on disability benefits to survive and advocate for universal civil rights exist in a paradox that cannot be sorted through research methodologies but forces us instead to contend with the political nature of research that is committed to social change.

Reparations for coloniality in global mental health research are due. Should the Global North be truly interested in leveling historical asymmetries and inequalities in the world, the first step should be the equitable distribution of research funding. HIC researchers must enter partnerships with the Global South from a place of curiosity and solidarity. Capacity building should be grounded in mutuality instead of technology/knowledge transfer. Participatory research in Brazil is rich and original. The challenges for its expansion and full implementation must be understood within a broader social context of disenfranchisement, poverty, and lack of fundamental rights. This field holds true to the Latin American origins of participation as a transformative and democratic exercise and to the tenets of the Psychiatric Reform movement that questioned the primacy of the biomedical model in mental health, exposed its contradictions, and paved the way to a community-based network of services that centered dignity and freedom as inalienable rights of every citizen. We hope to see participatory research in Brazil expand and flourish as it has in HICs, the rhizomes already exist.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.12.

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this review article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgements

This project is affiliated with and contributes to the Lancet Psychiatry Commission on Psychoses in Global Context.

Author contribution

A.C.F. had the original idea for the study and presented to all co-authors. G.J. assisted in the protocol writing and advised the team throughout. M.F. developed the search strategy and led the data management in EndNote and Covidence. D.C., R.T., and M.B. screened all title and abstracts and full texts along with A.C.F. A.C.F. and M.B. extracted the data. A.C.F. wrote the manuscript. All co-authors reviewed several iterations of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Financial support

This study was supported by the Foundation for Excellence in Mental Health Care.

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests exist.

Comments

December 20th, 2022

Dear Drs., Chibanda and Bass,

We wish to submit an original review entitled “State of the art of participatory and user-led research in mental health in Brazil: a scoping review” for consideration by Global Mental Health.

We confirm that this work is original and has not been published elsewhere, nor is it currently under consideration for publication elsewhere.

In this paper, we report on participation of individuals with lived experience of mental health challenges in research in Brazil. This is significant because the state of the art of this field is largely unknown in South America, however there’s clear indication it is a rich and productive area of research with distinct characteristics when compared to how this area has developed in the Global North.

Our review shows that participatory research in mental health in Brazil is strongly rooted in local scholarship. We present challenges to full participation that go beyond research. Brazilian service users face multiple and intersecting vulnerabilities that pose challenges to inclusion in society and in research alike. We believe this review can contribute to a more nuanced global debate about participation in Latin America.

Our team has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please address all correspondence concerning this manuscript to me at ana.florence@nyspi.columbia.edu.

Thank you for your invitation to submit this manuscript.

Sincerely,

Ana Carolina Florence, PhD