LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the role and possible mechanisms of action of yoga therapy in clinical psychiatric practice based on current evidence

• recognise yoga practices beneficial for common psychiatric disorders, their indications, contraindications and underlying rationale

• appreciate what kind of referral patterns might be expected for yoga therapy in a tertiary care psychiatric hospital.

The growing burden of mental illness worldwide has significant health, social, human rights and economic consequences, despite improvements in treatment and access to care (World Health Organization 2019). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one in four people experience a mental disorder at some point in their lives. The global disability-adjusted life-years attributed to mental disorders has increased from 3.1% in 1990 to 4.9% in 2019 (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators 2022). More than half of the world's countries lack sufficient skilled professionals to handle mental illnesses in the community, especially in low and lower middle income countries. More than 50% of countries have only one psychiatrist per 100 000 people and 40% of countries have less than one hospital bed reserved for mental disorders per 10 000 people (World Health Organization Reference World Health2015). For the past decade, there has been an emphasis on prevention in the WHO's Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020. In 2013, the WHO set objectives of providing comprehensive, integrated and responsive mental health and social care services in community-based settings and implementing strategies for promoting mental health and preventing mental illness (World Health Organization Reference World Health2013).

Yoga originated as a holistic system in India more than 3000 years ago. It is an ancient way of living in harmony with oneself (body, emotion and intellect) and nature (Satyananda Reference Satyananda2002). The fundamental components of yoga were summarised in a systematic eight-limbed approach (ashtanga yoga, which includes: ethical precepts – yama and niyama, physical postures – asana, breathing practices – pranayama, interoceptive awareness – pratyahara, focussed meditation – dharana, effortless meditative "flow" state – dhyana and the transcendental state – samadhi) by the Sage Patanjali in 400 bce (Satyananda Reference Satyananda2002). Patanjali's sutras (aphorisms) describe that main objective of yoga is to ‘calm down the agitations of the mind’ (sutra 1.2). All major schools of yoga that emphasise postures, breathing practices and cleansing techniques (as a preparation to the advanced meditative yoga of Sage Patanjali) are derived from hatha yoga. According to yoga philosophy, the word ‘hatha’ comes from ‘Ha’, which means the Sun, and ‘Tha’, meaning the Moon. Thus, all yogic practices aim to align an individual's biorhythms with those of nature, thereby improving overall health. Most schools of yoga incorporate elements of asanas (physical movements), including relaxation, pranayamas (breathing practices) and dhyana (meditation) to achieve this.

Although traditionally yoga was a discipline designed for spiritual growth, over the past two decades it has emerged as a promising complementary and alternative non-pharmacological option in the management and prevention of mental disorders (Varambally Reference Varambally, George and Gangadhar2020). Yoga therapy is free from stigma and has gained popularity across cultures. Other advantages of yoga therapy include the easy accessibility of trained professionals, cost-effectiveness (as it does not require any expensive equipment or maintenance costs) and the option of conducting yoga sessions in groups. The synchronisation of body movements, breath and mind together during a group yoga practice may lead to better sense of connectivity among people while practising yoga (coupling of the consciouness). Yoga can also be a helpful community-based intervention for providing comprehensive, holistic mental healthcare and promoting mental well-being and preventing mental illness (Varambally Reference Varambally, George and Gangadhar2020).

Studies have found a gap between the use of yoga by individuals with neuropsychiatric disorders and the prescription of yoga by trained mental health professionals (Sirven Reference Sirven, Drazkowski and Zimmerman2003). The primary reason for this gap is the lack of sufficient training and education of mental health professionals in yoga therapy.

This article aims to provide a scientific update on the role of yoga therapy for psychiatric disorders, along with the essential conceptual framework and clinical tips (based on our clinical experience of over a decade) for psychiatrists who seek to integrate yoga into their clinical practice.

Yoga in psychiatry: the evidence–base

Depression

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis (Brinsley Reference Brinsley, Schuch and Lederman2021) assessed the effects of yoga interventions based on physical postures in alleviating depressive symptoms. It included 19 studies (13 randomised controlled trials, RCTs) and 1080 participants with mental disorders such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, anxiety, alcohol dependence and bipolar disorder. The review authors found that yoga led to a greater reduction in depressive symptoms than treatment as usual, attention control or being on a waiting list. They also observed a dose–response relationship between the number of yoga sessions per week and a reduction in depressive symptoms. There is some preliminary evidence that yoga-based interventions may be a promising non-pharmacological option for depressive symptoms during pregnancy, especially for mild depression, as noted in a meta-analysis that included six studies (405 pregnant mothers) (Ng Reference Ng, Venkatanarayanan and Loke2019). Evidence is also emerging to support the usefulness of yoga as monotherapy for mild to moderate depression, as demonstrated by a few good-quality RCTs (Prathikanti Reference Prathikanti, Rivera and Cochran2017; Nyer Reference Nyer, Gerbarg and Silveri2018). One of these RCTs found that a 12-week Iyengar yoga and coherent breathing programme was a helpful solo intervention for resolving suicidal ideations in people with major depressive disorder. It also reported that the most common adverse event associated with yoga practice was musculoskeletal pain, which resolved over the study period (Nyer Reference Nyer, Gerbarg and Silveri2018).

Anxiety disorders

A systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the effect of yoga intervention on anxiety identified eight RCTs involving 319 participants with elevated anxiety levels or anxiety disorders (Cramer Reference Cramer, Lauche and Anheyer2018a). It found short-term beneficial effects of yoga in reducing anxiety in individuals with elevated levels of anxiety compared with no treatment and active comparators but no significant impact for individuals with clinical diagnosis of anxiety disorders (as per DSM-5 criteria). Based on this evidence, only a weak recommendation can be made at present for the clinical use of yoga in people diagnosed with anxiety disorders.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

A systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of yoga (7 RCTs; n = 284) in people with PTSD revealed low-level evidence for its clinical utility in reducing PTSD symptoms (Cramer Reference Cramer, Anheyer and Saha2018b).

Obsessive–compulsive disorder

Owing to the limited number of studies of yoga interventions for obsessive–compulsive disorder, no systematic reviews or meta-analyses have been published in this area. Though emerging evidence for an add-on utility of yoga is encouraging (Shannahoff-Khalsa Reference Shannahoff-Khalsa, Fernandes and Pereira2019; Shannahoff-Khalsa Reference Shannahoff-Khalsa, Ray and Levine1999), there is a need for more quality trials to make specific clinical recommendations.

Schizophrenia

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 RCTs involving 1081 people with schizophrenia found beneficial effects of meditation-based mind–body therapies (yoga, tai-chi, qi-gong and mindfulness) on negative symptoms compared with treatment as usual or non-specific control interventions (Sabe Reference Sabe, Sentissi and Kaiser2019). The review authors pointed out that there was moderate to high heterogeneity in these studies and that the effect size was small. Another meta-analysis found that mindful exercises such as yoga, tai-chi and qi-gong were more beneficial than non-mindful physical exercises in reducing psychiatric symptoms (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale scores) and improving working memory in this population. However, the quality of evidence was low (Li Reference Li, Shen and Wu2018). Overall, yoga can be considered helpful as an adjunctive therapy in reducing negative symptoms and improving the quality of life in people with schizophrenia. Most of the trials demonstrated clinical improvement after 8–12 weeks of yoga practice.

Chronic pain syndromes

A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for people with chronic non-specific neck pain has reported positive effects on pain intensity, pain-related functional disability, quality of life and mood (Li Reference Li, Li and Jiang2019). Similarly, meta-analyses have supported the beneficial short-term and long-term effects of yoga in reducing functional disability and pain in people with chronic non-specific lower back pain (Holtzman Reference Holtzman and Beggs2013: eight RCTs; Cramer Reference Cramer, Lauche and Haller2013: ten RCTs).

A recent meta-analysis assessed the effect of yoga in people with a diagnosis of chronic or episodic headache (tension-type headache and migraine). The pooled effect size of five RCTs revealed a significant overall effect favouring yoga on headache frequency, duration and pain intensity (Anheyer Reference Anheyer, Klose and Lauche2020). This overall effect is mainly attributable to patients with tension-type headaches. Similarly, a meta-analysis of four trials reported yoga to be highly effective in alleviating menstrual pain in women with primary dysmenorrhoea (Kim Reference Kim2019). Hence, in summary, yoga can serve as a valuable complementary treatment in managing chronic pain conditions.

Mild cognitive impairment and early dementia

The effect of common forms of mind–body exercises (yoga, tai-chi and qi-gong) on cognitive functions of people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has been evaluated in a systematic review and meta-analysis of nine RCTs and three non-RCTs (Zou Reference Zou, Loprinzi and Yeung2019). The review authors observed that there was a significant improvement in the following domains of cognition (in decreasing order of pooled effect size): (a) attention; (b) short-term memory; (c) executive function; (d) visuospatial function; and (e) global cognitive function. This indicates that mind–body interventions such as yoga, tai-chi and qi-gong can improve cognitive function in people with MCI. The evidence points to the potential role of such interventions in delaying the progression from MCI to Alzheimer's disease or other types of dementia.

Substance use disorders

A review of the evidence over the past 10 years for yoga in smoking cessation concluded that it is a promising intervention for improving smoking cessation rates (Dai Reference Dai and Sharma2014). Similarly, reviews of studies of yoga for various substance use disorders (four RCTs involving people with nicotine dependence, four RCTs in people with alcohol dependence and two RCTs in people with opioid use disorder) have concluded that yoga can be a useful adjuvant intervention in reducing addiction severity and improving quality of life (Sarkar Reference Sarkar and Varshney2017; Kuppili Reference Kuppili, Parmar and Gupta2018). Thus, there is preliminary evidence for the utility of yoga as an adjunctive treatment in substance use disorders.

Psychiatric disorders in children and adolescents

A systematic review of 27 studies assessing the effects of yoga interventions on anxiety and depression in young people found that 70% of the studies reported overall improvements. Among the studies evaluating anxiety and depression, 58% showed improvement, whereas 70 and 40% of the studies assessing anxiety alone and depression alone reported improvements. The review authors concluded that regardless of intervention characteristics, yoga improves anxiety and depression in young people (James-Palmer Reference James-Palmer, Anderson and Zucker2020).

A systematic review that included four RCTs (two involving mantra meditation and two using yoga) could not draw any firm conclusion for the recommendation of yoga in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Krisanaprakornkit Reference Krisanaprakornkit, Ngamjarus and Witoonchart2010). Thus, the current evidence is not sufficient to make clinical recommendations for ADHD, but this is an important area for future research.

A review article in the area of yoga, mindfulness and autism spectrum disorders identified eight empirical studies that showed promising early results on social, emotional or behavioral metrics(Semple Reference Semple2019). Though empirical evidence from the review was inconclusive, authors suggested need for further research.

This review of the evidence indicates that yoga can be useful for reducing anxiety and depression in children and adolescents but no conclusions can be drawn for its utility in ADHD or autism spectrum disorders at present.

Sleep disorders

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effects of mind–body therapies on sleep quality in healthy individuals and in people with insomnia (Wang Reference Wang, Li and Pan2019). It found 49 studies (4506 participants) with interventions such as meditation, tai-chi, qi-gong and yoga. The review authors concluded that these interventions produced a statistically significant improvement in sleep quality and reduction in insomnia severity, with more significant effects on healthy people than the clinical population. Thus, yoga can be recommended for enhancing the quality of sleep in healthy individuals and in people with insomnia.

Clinical yoga techniques for common psychiatric disorders

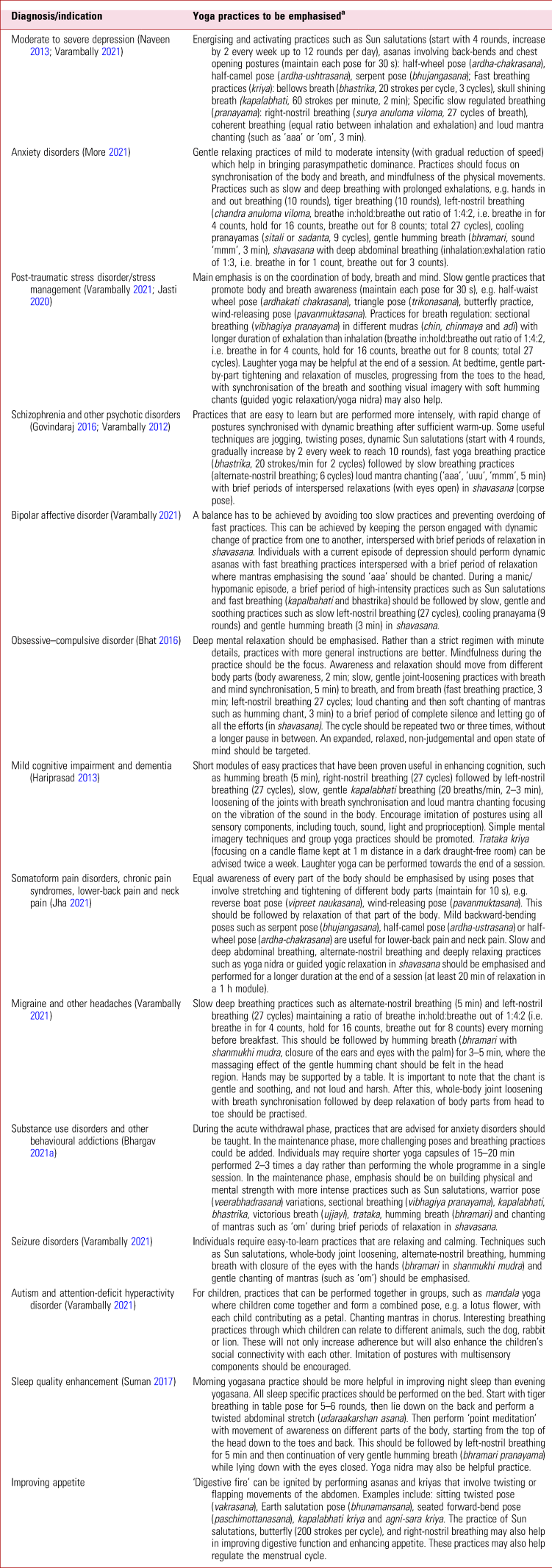

Although evidence points to the utility of yoga for various psychiatric conditions, it is difficult to say precisely what form of yoga should be recommended for specific symptoms or disorders. This is primarily due to the heterogeneity in the styles of yoga used in different studies and the lack of quality studies comparing different styles of yoga. Given these caveats, the suggestions below are based on our combined experience of clinical psychiatry and yoga therapy, and the self-reports of our patients. Table 1 offers some tips on the kind of yoga practices that should be emphasised in specific psychiatric disorders. We believe these will help clinicians understand therapeutic yoga techniques that can benefit their patients. Preliminary research shows that, on average, 8–12 weeks of yoga practice, with a minimum of three 1 h sessions per week, are required to produce observable benefits in major psychiatric conditions (Streeter Reference Streeter, Gerbarg and Brown2020; Arasappa Reference Arasappa, Bhargav and Ramachandra2021).

TABLE 1 Yoga practices to be emphasised for various psychiatric disorders

a Yogic practices should be performed at least three times per week for sustained effects. Fast breathing practices should not be performed less than 2 h after a meal.

Safety and adverse events

A systematic review assessing the frequency of adverse events in RCTs of yoga (94 RCTs published between 1975 and 2014 and involving 8430 participants) concluded that yoga was as safe as usual care and exercise (Cramer Reference Cramer, Ward and Saper2015). A few studies have reported aggravation of psychotic symptoms after meditative practices among patients with pre-existing psychotic disorders: a narrative review of 19 studies and 28 cases observed that the types of meditation involved were transcendent, mindfulness, Buddhist meditation such as vipassana, qigong, zen and theraveda, and practices such as bikram yoga, pranic healing and Hindustan-type meditation. However, the review authors noted that it was difficult to attribute a causal relationship between the meditation and worsening of psychotic symptoms and suggested further studies (Sharma Reference Sharma, Mahapatra and Gupta2019). Similarly, indirect evidence indicates that hyperventilation can be a cause, a correlate or a consequence of panic attacks, and practices reversing hyperventilation may be effective (Meuret Reference Meuret and Ritz2010). Fast yoga breathing practices such as kapalbhati and bhastrika involve hyperventilation, whereas kumbhaka (holding of the breath) reverses the hyperventilation process. Kumbhaka has been used as a part of regulated breathing and slow pranayama in yoga. Thus, faster yoga breathing may be avoided, whereas slow pranayama may be promoted in anxiety disorders, including panic disorder. Learning yoga from media sources such as YouTube and self-practice without supervision can result in serious side-effects due to incorrect practices and should be avoided (Suchandra Reference Suchandra, Bojappen and Rajmohan2021).

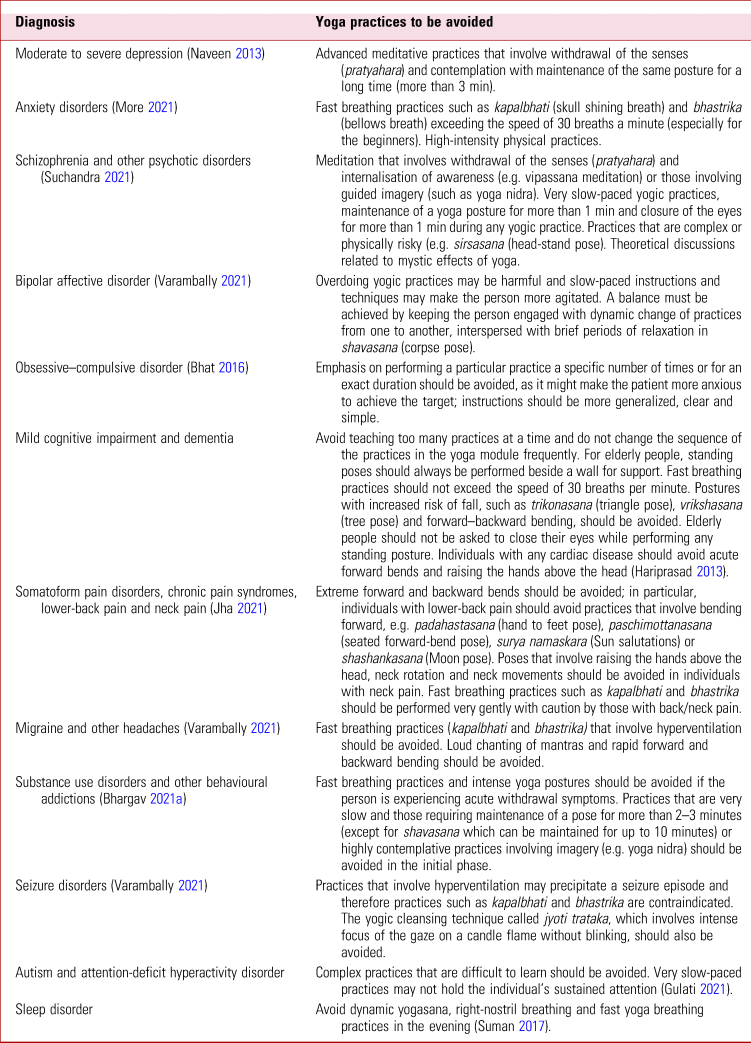

It is important for clinicians to understand the potentially harmful effects of yoga practices and Table 2 lists practices that may preferably be avoided in patients with particular psychiatric disorders.

TABLE 2 Yoga practices to be avoided and precautions to be followed for various psychiatric disorders

Possible neurobiological mechanisms of action of yoga in mental disorders

Downregulation of the HPA axis

Yoga has been found to reduce cortisol levels by downregulating the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Studies have also shown that yoga practice (from the acute effect of a single session to 6 months of regular practice) can reduce cortisol levels in people with psychiatric disorders (Thirthalli Reference Thirthalli, Naveen and Rao2013; Bershadsky Reference Bershadsky, Trumpfheller and Kimble2014).

Increase in BDNF levels

Studies have also demonstrated that yoga practice of 12 weeks can enhance neuroplasticity (levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, BDNF) in people with major depressive disorder (Naveen Reference Naveen, Varambally and Thirthalli2016; Tolahunase Reference Tolahunase, Sagar and Faiq2018).

Enhancement of GABAergic transmission

Another major central mechanism through which yoga produces a calming and relaxing effect is by enhancing the levels of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Studies have also found that Iyengar yoga intervention, varying from a single session to 12 weeks, can increase thalamic GABA levels in healthy individuals (Streeter Reference Streeter, Jensen and Perlmutter2007; Streeter Reference Streeter, Whitfield and Owen2010). Similar findings have also been observed with 12 weeks of yoga practice in patients with major depressive disorder (Streeter Reference Streeter, Gerbarg and Brown2020). This GABAergic mechanism of yoga has also been demonstrated using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) in people with depressive disorder (Bhargav Reference Bhargav, Reddy and Govindaraj2021b).

Reduction in inflammatory cytokines

Inflammation is another biological process that is associated with psychiatric conditions. Two RCTs demonstrated a reduction in interleukin-6 (IL-6) after 10 weeks of hatha yoga (Nugent Reference Nugent, Brick and Armey2021) and 12 weeks of yoga and meditation-based lifestyle (Tolahunase Reference Tolahunase, Sagar and Faiq2018) in people with major depressive disorder.

Modulation of autonomic nervous system functions

Certain yoga practices, especially breathing through a specific nostril or at a particular frequency, have shown differential effects on the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (Raghuraj Reference Raghuraj and Telles2008). Slow yoga breathing practices may result in a state of parasympathetic dominance (Kromenacker Reference Kromenacker, Sanova and Marcus2018), whereas faster yoga breathing practices (kriyas) may produce the opposite effect.

Morphological and functional brain changes

In a recent review article, 34 international peer-reviewed neuroimaging studies of the effects of yoga on the brain using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), positron emission tomography (PET) or single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) were analysed. Three consistent findings from the studies were: (a) increased grey matter volume in the insula and hippocampus; (b) increased activation of prefrontal cortical regions; and (c) functional connectivity changes in the default mode network (van Aalst Reference van Aalst, Ceccarini and Demyttenaere2020).

Further information

Further details on mechanisms of action may be found in a recent review article summarising biomarker evidence for the effects of yoga in psychiatric disorders (Bhargav Reference Bhargav, George and Varambally2021c).

Yoga in current psychiatric treatment guidelines

In 2016, the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) updated its evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depressive disorders. Section 5 of the guidelines deals with two broad categories of intervention using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): (a) physical and meditative treatments and (b) natural health products. For major depressive disorder of mild to moderate severity, the guidelines recommend exercise, (bright) light therapy, St John's wort, omega-3 fatty acids, S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) and yoga as first- or second-line treatments (Ravindran Reference Ravindran, Balneaves and Faulkner2016). Similarly, for adults with depression for whom psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy is either ineffective or unacceptable, the American Psychological Association's guidelines include a ‘conditional recommendation for use’ of exercise, St John's Wort, bright light therapy or yoga (Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders 2019). Yoga is also recommended as a complementary intervention for the management of schizophrenia in the UK's updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines (NCCMH Reference National Collaborating2014).

Barriers and limitations to the use of yoga in psychiatry

At an individual level, yoga requires significant motivation and effort. It also requires dedicated time and space for practice. In a survey of people with schizophrenia, it was observed that travel distance from home to the yoga centre was the primary barrier to yoga practice (Baspure Reference Baspure, Jagannathan and Kumar2012). Complex and challenging practices pose other obstacles. To overcome these barriers and enhance motivation, the yoga therapist should initially spend a good amount of time with the patient in rapport building and start with simple and easy yoga practices. Tele-yoga might be used to overcome the barriers of distance and time, with more frequent short sessions rather than a single long session. However, there is currently a disconnect between psychiatric care facilities and yoga services in most of the world. There are many reasons for this, such as the lack of trained yoga therapists/mental health professionals in most hospitals (perhaps because of funding limitations) and also the lack of awareness among mental health professionals about the benefits and precautions of yoga in relation to psychiatric disorders. We hope this article will help improve the connection (the root of the word ‘yoga’ means ‘to connect’). A limitation of yoga therapy is lack of standardisation of practices for given clinical conditions. Clinical trials of yoga in psychiatric disorders use various interventions, ranging from predominantly asana-based approaches (the Iyengar school) to practices that are purely contemplative and meditative (Rajayoga meditation). This heterogeneity in published trials hinders application in clinical settings and calls for standardisation of modules and replication of studies.

How yoga services evolved at our tertiary mental healthcare hospital

The National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) is a major tertiary mental healthcare hospital in South India, with 932 in-patient beds and an average of 1500 patients attending out-patient services every day. The integration of yoga into clinical practice began in 2007 with the establishment of a centre funded by the Government of India's Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha and Homeopathy (AYUSH). Initially, services were provided on the basis of referrals (only one or two patients per day) from the NIMHANS’ Departments of Psychiatry, Neurology and Psychology and were limited to patients with non-specific complaints or those who asked for yoga or those who had mild anxiety or depression and were unwilling to take medications. Referrals increased over the years and the centre was absorbed into NIMHANS’ core services in 2014. In-patients and out-patients at NIMHANS were referred to the yoga centre by psychiatrists, psychologists, neurologists and neurosurgeons. In 2019, the yoga centre evolved into a separate clinical department – the Department of Integrative Medicine at NIMHANS – which integrates biomedicine, yoga and Ayurveda, with faculty and scientists from all three disciplines.

After coming to the yoga centre, the patient is first seen by the senior resident in psychiatry, who assesses the severity of illness and rules out contraindications for yoga. After assessment the patient is sent to a senior/junior scientific officer (MD yoga), who formulates the yoga programme and offers yoga-based lifestyle tips related to physical activity, diet, stress and sleep based on the assessment of the individual's constitution from traditional viewpoints (gunas – mental attitudes; doshas – physical factors). The patient is then introduced to the yoga therapist (Master's degree in yoga) who delivers the yoga sessions. Patient is given a yoga registration card that shows the patient's details, the name of the therapist, the time of sessions and an attendance chart. The first session is conducted by the therapist one-on-one, either on the day the patient first visits the department or the next day. In the first session, the therapist demonstrates indicated and contraindicated practices from the yoga module for the specific condition (e.g. the depression or anxiety module) and any errors in the patient's practice are corrected. Subsequently, from day 2, the patient joins 1 h group sessions for their particular condition. For most people, ten supervised yoga sessions are sufficient to learn and practice the module on their own at home with the help of a practice chart or a video. Individuals with chronic psychoses and elderly people with cognitive impairment often need a month of supervised practice (approximately 20 sessions) to learn the module. For children with autism, 3–4 months are usually required to accustom the child to the class and practice, and substantial improvements in imitation are often observed only after 6–9 months of regular practice.

Indications for yoga referral

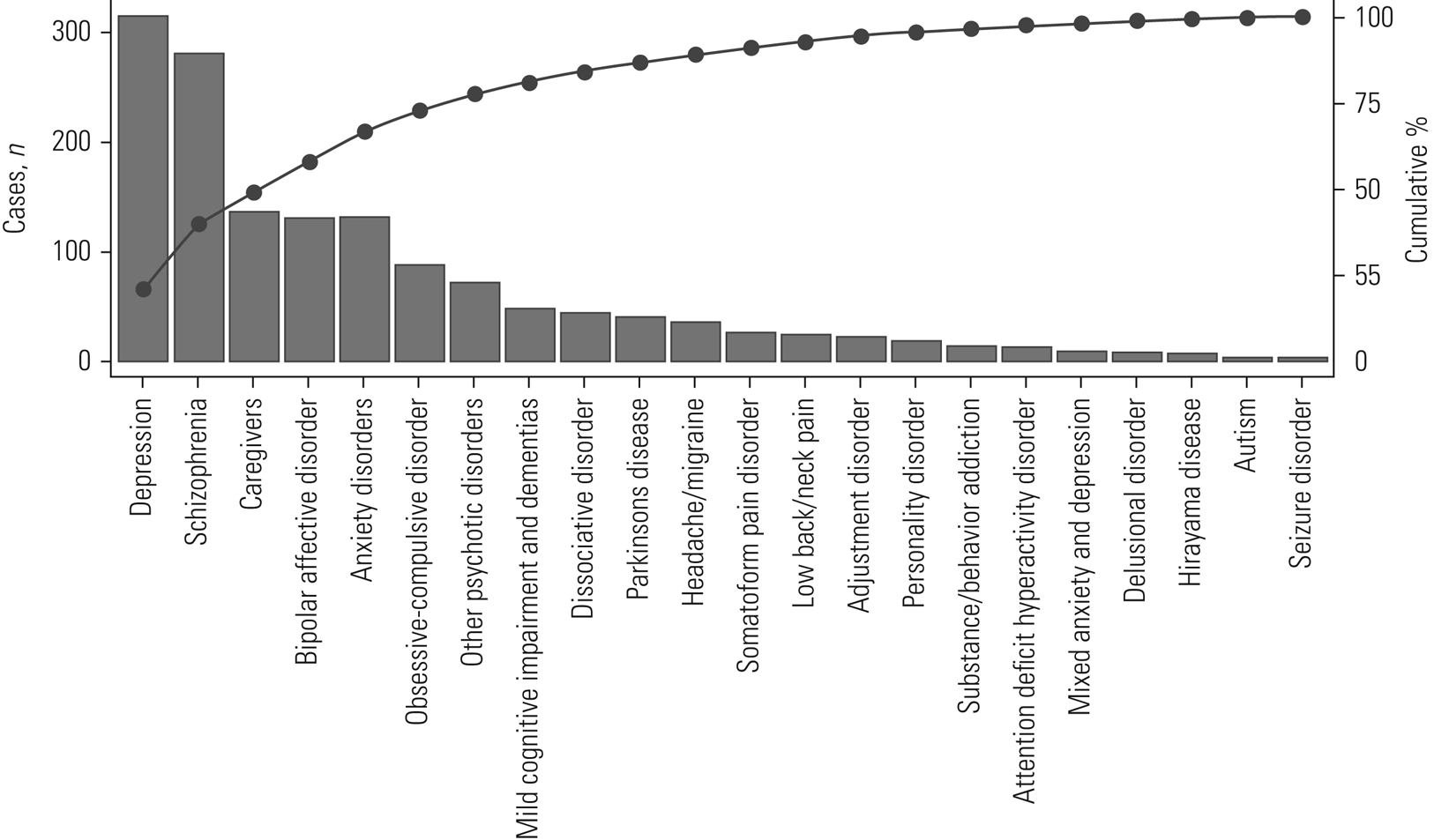

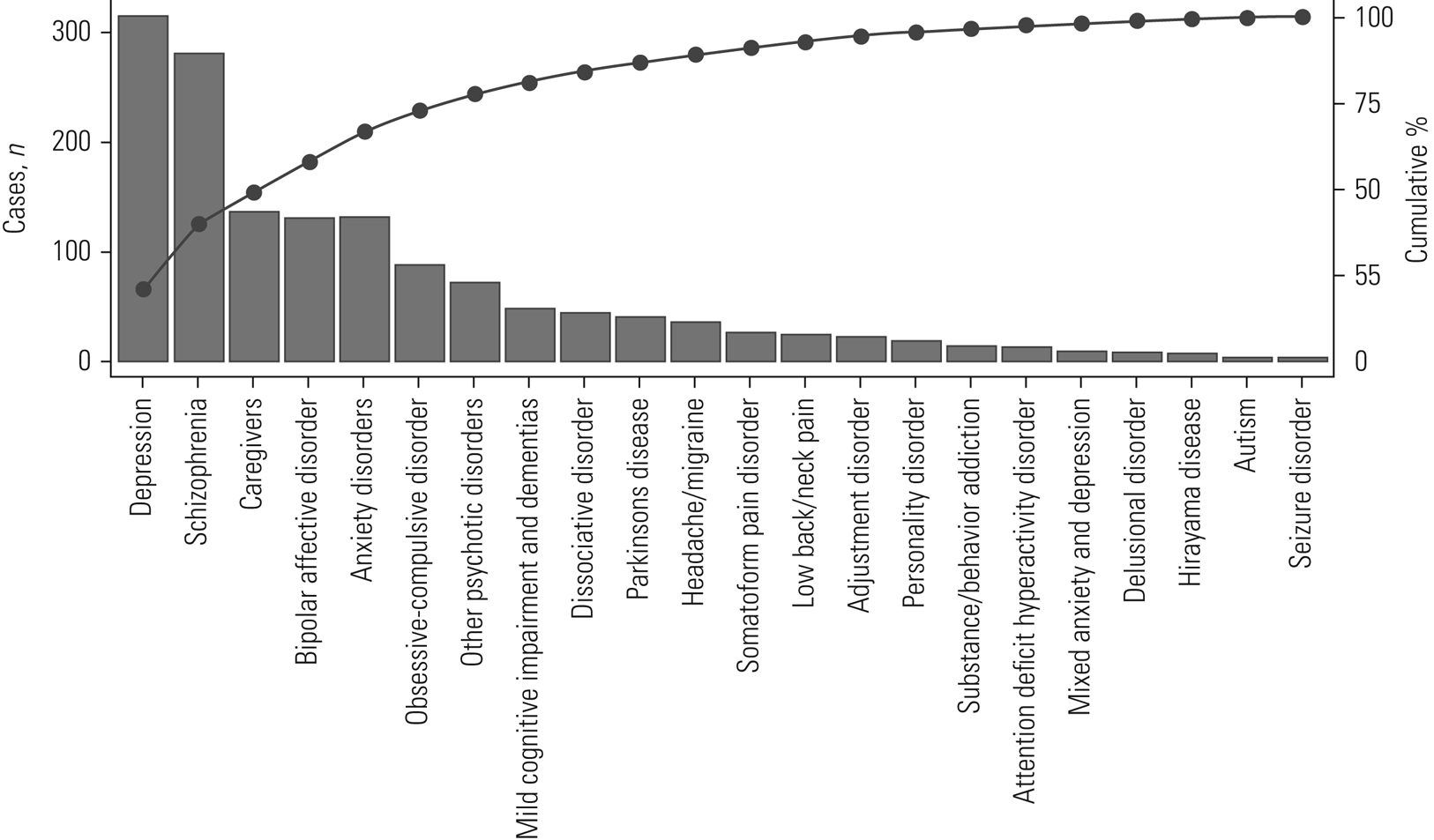

More than 70% of individuals referred for yoga therapy to the Department of Integrative Medicine at NIMHANS are treated primarily for one of the following disorders: (a) depressive disorders; (b) schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; (c) anxiety disorders or obsessive–compulsive disorder; (d) mild cognitive impairment. The first two categories account for more than half of total referrals (53%). Hence, a yoga therapy centre in a tertiary mental healthcare setting could expect depression and schizophrenia (with other psychotic disorders) to be the most important psychiatric disorders for which yoga therapy is sought as an adjunctive treatment. Figure 1 shows the distribution of referrals by diagnosis in 2019. Apart from the conditions depicted in Fig. 1, about 1% of referrals were for the following diagnoses: ADHD, seizure disorder, Hirayama disease and autism spectrum disorders.

FIG 1 Pareto chart showing the diagnosis-specific pattern of referrals for yoga therapy to the Department of Integrative Medicine at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, a tertiary mental and neurological healthcare hospital in South India, from 1 January to 31 December 2019.

Role of a yoga-based lifestyle in preventive psychiatry

Preventive psychiatry is a branch of psychiatry that aims at health promotion, protection from specific mental illnesses, early diagnosis, effective treatment, disability limitation and rehabilitation. Prevention in neuropsychiatric conditions is particularly important as many of them run a chronic disabling course. Lifestyle factors, including psychosocial environment and stress, play key roles in the causation of psychiatric disorders. A yoga-based lifestyle has been found to be helpful in reducing lifestyle-related risk factors in major non-communicable diseases, and several studies have demonstrated the utility of yoga in combating psychological stress (Cocchiara Reference Cocchiara, Peruzzo and Mannocci2019). Freedom from stigma, and the increasing popularity of tele-yoga in recent times, have made yoga more acceptable and accessible to people. Although potentially useful, research into the role of yoga in preventive psychiatry is limited.

Future directions in integrative psychiatry

Given the safety and beneficial effects of yoga in treatment of psychiatric disorders and promotion of mental well-being, we anticipate that it will become an integral part of multidisciplinary psychiatric care in the near future, similar to clinical psychology and psychiatric social work. However, this needs continuing generation of evidence on both the efficacy and mechanisms of action of yoga in mental health disorders.

Authors contributions

All authors contributed to the conception of this artcile, writing the first draft, revision and preparing the final version of this manuscript.

Funding

This article received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. However, H.B. and S.V. are supported by the Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance, respectively receiving an Early Career and an Intermediate Career Fellowship. The Department of Integrative Medicine at NIMHANS is supported by the Ministry of AYUSH, Government of India, through funding for the Centre of Excellence in AYUSH Research.

Declaration of interest

S.G. is a member of the BJPsych Advances editorial board and did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this article.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem:

1 Which of the following is not a part of eight-limbed approach of yoga (Ashtanga yoga)?

a physical posture (asana)

b withdrawal of the senses (pratyahara)

c focused concentration (dharana)

d perception through the senses (pramana)

e ethical precepts (yama).

2 It is advisable to avoid the practice of meditation in:

a anxiety disorders

b depression

c schizophrenia

d somatoform pain disorder

e post-traumatic stress disorder.

3 The following yogic practice should be emphasised more in anxiety disorders:

a right-nostril breathing

b left-nostril breathing

c bellows breath (bhastrika)

d skull shining breath (kapalabhati)

e loud mantra chanting.

4 Fast yoga breathing practices such as bellows breath and skull shining breath should be avoided in:

a depression

b chronic psychotic disorders

c substance use disorders

d panic/anxiety disorder

e mild cognitive impairment.

5 Strongest evidence for the beneficial effects of yoga has been observed in:

a anxiety disorders

b chronic psychotic disorders

c substance use disorders

d depression

e mild cognitive impairment.

MCQ answers

1 d 2 c 3 b 4 d 5 d

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.