Childhood maltreatment encompasses various early adverse experiences, including physical and emotional neglect, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse, as well as witnessing domestic violence. Maltreatment is one of the most profound insults to normal development, and it is strongly associated with several maladaptive outcomes including poor mental and physical health as well as reduced economic productivity across the life span (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Lansford et al., Reference Lansford, Dodge, Pettit, Bates, Crozier and Kaplow2002; Widom, Czaja, Bentley, & Johnson, Reference Widom, Czaja, Bentley and Johnson2012). It is noteworthy that individuals with a psychiatric disorder who have experienced childhood maltreatment show higher rates of comorbidity and symptom severity (Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough, & Riccardi, Reference Cougle, Timpano, Sachs-Ericsson, Keough and Riccardi2010; Teicher & Samson, Reference Teicher and Samson2013) and are less likely to respond to treatment (Nanni, Uher, & Danese, Reference Nanni, Uher and Danese2012). Furthermore, epidemiological data have estimated that childhood abuse and neglect account for up to 45% of the risk of childhood-onset psychiatric disorders and for approximately 30% of adult and adolescent-onset disorders (Green et al., Reference Green, McLaughlin, Berglund, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Kessler2010). In line with these findings, population-attributable risk assessments from large cross-cultural data sets have indicated that eradicating childhood abuse and neglect could reduce the occurrence of childhood-onset psychopathology by more than 50% (Kessler et al., Reference Kessler, McLaughlin, Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky and Williams2010).

The Theory of Latent Vulnerability

Despite the abundance of evidence linking early adversity with negative outcome, there is a relative paucity of knowledge regarding the mechanisms through which increased psychiatric vulnerability becomes instantiated. The theory of latent vulnerability (McCrory & Viding, Reference McCrory and Viding2015; McCrory, Gerin, & Viding, Reference McCrory, Gerin and Viding2017) offers a systems-level approach that places emphasis on the neurocognitive mechanisms that link early adversity to future psychopathology. According to this account, childhood maltreatment leads to alterations in several neurobiological and cognitive systems, which are understood as developmental recalibrations to abusive and neglectful environments. Such changes are “latent” insofar as they do not inevitably result in a manifest psychological disorder and can even confer short-term functional advantages within early adverse environments. Yet, in the long-term, they come at a cost as they heighten psychiatric risk.

The majority of neuroimaging studies of childhood abuse and neglect have focused on (a) perceptual/attentional processes, such as threat detection (e.g., Dannlowski et al., Reference Dannlowski, Stuhrmann, Beutelmann, Zwanzger, Lenzen, Grotegerd and Kugel2012, Reference Dannlowski, Kugel, Huber, Stuhrmann, Redlich, Grotegerd and Suslow2013, McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011, Reference McCrory, De Brito, Kelly, Bird, Sebastian, Mechelli and Viding2013; Tottenham et al., Reference Tottenham, Hare, Millner, Gilhooly, Zevin and Casey2011); (b) low-level executive functions, especially response inhibition (Elton et al., Reference Elton, Tripathi, Mletzko, Young, Cisler, James and Kilts2014; Lim et al., Reference Lim, Hart, Mehta, Simmons, Mirza and Rubia2015; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Maheu, Dozier, Peloso, Mandell, Leibenluft and Ernst2010); and, more recently, (c) affect regulation (McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves, & Sheridan, Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015; Puetz et al., Reference Puetz, Kohn, Dahmen, Zvyagintsev, Schüppen, Schultz and Konrad2014, Reference Puetz, Viding, Palmer, Kelly, Lickley, Koutoufa and Mccrory2016) and (d) reward processing (Dennison et al., Reference Dennison, Sheridan, Busso, Jenness, Peverill, Rosen and McLaughlin2016; Goff et al., Reference Goff, Gee, Telzer, Humphreys, Gabard-Durnam, Flannery and Tottenham2013; Hanson, Hariri, & Williamson, Reference Hanson, Hariri and Williamson2015; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Gore-Langton, Golembo, Colvert, Williams and Sonuga-Barke2010). A number of consistent findings have emerged from these studies (see McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Gerin and Viding2017, for a recent review). First, in relation to threat processing, several studies have reported increased neural response (particularly in the amygdala) to threat-related cues, such as angry faces. Second, studies of explicit affect regulation and executive control have reported a pattern of increased activation in medial frontal regions, including the superior frontal gyrus and cingulate cortex in individuals who have experienced maltreatment. By contrast, during more implicit regulatory processes, maltreatment experience has typically been associated with a pattern of reduced activation in a widespread frontolimbic network. Third, studies of reward processing have generally reported reduced activation in subcortical reward-related areas, in particular the striatum. These alterations in neural function are consistent with those reported in studies of individuals presenting with common psychiatric disorders (such as anxiety and depression) and may therefore represent markers of latent vulnerability to future psychopathology (McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, Gerin and Viding2017; McCrory & Viding, Reference McCrory and Viding2015).

However, in addition to these domains of functioning, it is possible that the neurocognitive processes implicated in how an individual learns from his or her experience, may also be compromised in children exposed to maltreatment given their frequent exposure to chaotic and unpredictable environments (Cyr et al., Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Ackerman, Izard and Bakermans-Kranenburg2010; Solomon & George, Reference Solomon, George, Solomon and George1999). In recent years a series of studies have documented how altered reinforcement-based decision making is implicated in a number of disorders associated with maltreatment, such as anxiety and depression (Eshel & Roiser, Reference Eshel and Roiser2010; Hartley & Phelps, Reference Hartley and Phelps2012). This suggests that altered reinforcement-based decision making may index latent vulnerability to psychiatric disorder following childhood maltreatment experience.

Reinforcement-Based Decision Making and Maltreatment

Evidence from neurodevelopmental sciences, psycholinguistics and even cognitive developmental robotics, suggest that our ability to detect patterns in the environment (i.e., contingency detection) is crucial for the acquisition of a number of skills, ranging from basic perpetual abilities to higher order cognitive functions, including language, affect regulation, and relevant to this study, reinforcement-based decision making (Ellis, Reference Ellis2006; Nagai, Asada, & Hosoda, Reference Nagai, Asada and Hosoda2006; Reeb-Sutherland, Levitt, & Fox, Reference Reeb-Sutherland, Levitt and Fox2012). Despite preliminary findings linking maltreatment to neural changes in the context of reward processing (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Holmes, Birk, Brooks, Lyons-Ruth and Pizzagalli2009; Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hariri and Williamson2015) and outcome monitoring (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Hart, Mehta, Simmons, Mirza and Rubia2015), no prior study has investigated alterations in the neural systems mediating reinforcement-based decision making and its computational components in maltreated individuals.

During normal development, our innate ability for contingency detection is fostered through sensitive caretaking. However, maltreatment experiences disrupt the species normative learning environment as the child is exposed to extreme and erratic parental affective reactions and/or a paucity or inconsistency in the availability of primary reinforcers. In the case of physical maltreatment, punishments are unpredictable and extreme, compromising contingency learning by biasing attention toward negative cues (e.g., McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011; Shackman, Shackman, & Pollak, Reference Shackman, Shackman and Pollak2007). This in turn may limit the resources available (allostatic load) for the development of a range of normative cognitive functions (Rogosch, Dackis, & Cicchetti, Reference Rogosch, Dackis and Cicchetti2011), and reduce the opportunities necessary for learning by inducing a more avoidant exploratory style (Cicchetti & Doyle, Reference Cicchetti and Doyle2016; Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006; Cyr et al., Reference Cyr, Euser, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Ackerman, Izard and Bakermans-Kranenburg2010). In the case of physical and emotional neglect, which represent common forms of maltreatment, basic reinforcers, such as food and emotional warmth, are not only less frequent but also less predictable (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Radford, Corral, Bradley, & Fisher, Reference Radford, Corral, Bradley and Fisher2011). These conditions are likely to contribute to the formation of abnormal expectancies representation of stimulus–outcome (S-O) and responses–outcome (R-O) associations. In other words, it is possible that maltreatment experience leads to alterations in the neurocomputational processes critical for reinforcement-based decision making.

Neurocomputational Processes of Reinforcement-Based Decision Making

Behavioral and computational neuroimaging research suggests that at least two processes underlie successful reinforcement-based decision making: (a) expected value (EV) representation (i.e., the reinforcement expectancies associated with a stimulus or action) and (b) prediction error (PE; i.e., the ability to detect the difference between the actual from the expected outcome associated with a stimulus or action; Clithero & Rangel, Reference Clithero and Rangel2013; O'Doherty, Hampton, & Kim, Reference O'Doherty, Hampton and Kim2007; Rescorla & Wagner, Reference Rescorla and Wagner1972).

These two components are highly interdependent: PE signals are thought to alter the EV associated with a stimulus or action while EV representation is directly related to the strength of the PE response to a given outcome. Evidence from computational model-based studies and animal models have shown that these two processes engage overlapping frontostriatal circuitry with its central nodes in the dorsal striatum (DS) and ventral striatum (VS) and the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC; Clithero & Rangel, Reference Clithero and Rangel2013; O'Doherty, Reference O'Doherty2011; O'Doherty et al., Reference O'Doherty, Dayan, Schultz, Deichmann, Friston and Dolan2004; Tanaka et al., Reference Tanaka, Doya, Okada, Ueda, Okamoto, Yamawaki, Ikeda, Kato, Ohtake and Tsutsui2016; Valentin & O'Doherty, Reference Valentin and O'Doherty2009). Other brain areas implicated in PE and EV signaling include the globus pallidus, thalamus, and medial and lateral temporal regions, such as the hippocampus, insula, and superior temporal gyrus (Amiez et al., Reference Amiez, Neveu, Warrot, Petrides, Knoblauch and Procyk2013; Bach et al., Reference Bach, Guitart-Masip, Packard, Miró, Falip, Fuentemilla and Dolan2014; Glimcher, Reference Glimcher2011; Zénon et al., Reference Zénon, Duclos, Carron, Witjas, Baunez, Régis and Eusebio2016). Nodes associated with the salience network have consistently been implicated during PE signaling, including the amygdala, insula, and dorsal portions of the cingulate gyrus (Amiez et al., Reference Amiez, Neveu, Warrot, Petrides, Knoblauch and Procyk2013; Garrison, Erdeniz, & Done, Reference Garrison, Erdeniz and Done2013; Kosson et al., Reference Kosson, Budhani, Nakic, Chen, Saad, Vythilingam and Blair2006).

Reinforcement-Based Decision Making and Psychiatric Disorder

Extant neuroimaging and behavioral data suggest that alterations in the mechanisms underlying reinforcement-based learning and decision making may contribute to the emergence and the maintenance of psychiatric conditions commonly associated with childhood maltreatment, such as anxiety, depression, conduct problems, and substance abuse (Eshel & Roiser, Reference Eshel and Roiser2010; Grant, Contoreggi, & London, Reference Grant, Contoreggi and London2000; Hartley & Phelps, Reference Hartley and Phelps2012; Matthys, Vanderschuren, & Schutter, Reference Matthys, Vanderschuren and Schutter2012; Schoenbaum, Roesch, & Stalnaker, Reference Schoenbaum, Roesch and Stalnaker2006). Neuroimaging studies of these disorders have typically reported a pattern of decreased neural activation during reinforcement expectancies representation and outcome anticipation in the orbitostriatal circuitry (Benson, Guyer, Nelson, Pine, & Ernst, Reference Benson, Guyer, Nelson, Pine and Ernst2014; Finger et al., Reference Finger, Marsh, Blair, Reid, Sims, Ng and Blair2011; Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Christopher May, Siegle, Ladouceur, Ryan, Carter and Dahl2006, Reference Forbes, Hariri, Martin, Silk, Moyles, Fisher and Dahl2009; Galván & Peris, Reference Galván and Peris2014; May, Stewart, Migliorini, Tapert, & Paulus, Reference May, Stewart, Migliorini, Tapert and Paulus2013; Schoenbaum et al., Reference Schoenbaum, Roesch and Stalnaker2006; Smoski et al., Reference Smoski, Felder, Bizzell, Green, Ernst, Lynch and Dichter2009; Smoski, Rittenberg, & Dichter, Reference Smoski, Rittenberg and Dichter2011; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas Belil, Artiges, Lemaitre, Gollier-Briant, Wolke and Paillère-Martinot2015). Reduced neural response in the striatum (especially the caudate), OFC, and the insula have also been reported in recent computational functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of EV and PE representation in anxiety, conduct disorder, and addiction (White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Fowler, Sinclair, Schechter, Majestic, Pine and Blair2014, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017; White, Tyler, Botkin, et al., Reference White, Tyler, Botkin, Erway, Thornton, Kolli and Blair2016; White, Tyler, Erway, et al., Reference White, Tyler, Erway, Botkin, Kolli, Meffert and Blair2016). This is in line with animal models of early adversity (e.g., Pani, Porcella, & Gessa, Reference Pani, Porcella and Gessa2000) and with neuroimaging data of reward processing with institutionalized individuals (Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Gore-Langton, Golembo, Colvert, Williams and Sonuga-Barke2010).

Hypotheses

In the current study, we examined reinforcement-based decision making, and its neurocomputational correlates, as a potential candidate system for indexing latent vulnerability among maltreated individuals. In order to investigate maltreatment-related changes in EV and PE neural signaling, children (10–15 years) with and without documented abuse and neglect were presented in the scanner with a probabilistic passive avoidance task. This task has been used previously with individuals of similar age ranges, as well as with patients with psychiatric condition associated with maltreatment (White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017). Briefly, participants were required to learn what stimuli were associated with a higher probability of winning or losing points, and respond to (actively approach) the reward stimuli and withhold the response to (passively avoid) the punishment stimuli.

A model-based fMRI analytic method was implemented to assess the computational processes underlying EV and PE representations. Such an approach offers the opportunity to generate regressors of interest that go beyond stimulus inputs and behavioral responses. This can help uncover hidden functions and variables by showing how the brain implements a particular process (O'Doherty et al., Reference O'Doherty, Hampton and Kim2007). A model-based approach allowed us to detect with greater sensitivity the neural signal underlying the computations necessary for EV and PE representation.

We hypothesized that for both approached and avoided stimuli, children with maltreatment experience would show reduced modulation of blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) responses by EV in four regions of interest (ROIs): the DS and VS striatum, the medial OFC (mOFC), and the lateral OFC (lOFC). As noted earlier, this is in line with evidence from studies of reinforcement expectancies representation in those psychiatric disorders associated with maltreatment, with the animal literature of early adversity, and with some preliminary evidence from studies of extreme neglect (e.g., Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Hariri, Martin, Silk, Moyles, Fisher and Dahl2009; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Gore-Langton, Golembo, Colvert, Williams and Sonuga-Barke2010; Smoski et al., Reference Smoski, Rittenberg and Dichter2011; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas Belil, Artiges, Lemaitre, Gollier-Briant, Wolke and Paillère-Martinot2015; White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017). In addition, consistent with substantial evidence of increased neural activation to negative stimuli and negative feedback among abused and neglected children (e.g., Lim et al., Reference Lim, Hart, Mehta, Simmons, Mirza and Rubia2015; McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015), we hypothesized that children with maltreatment experience would show increased modulation of BOLD responses by PE during punishment feedback in four ROIs: the amygdala, the insula, and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and midcingulate cortex (MCC).

In addition, we conducted a number of exploratory analyses related to PE modulated brain response for reward feedback. Extant data from animal models of early adversity and from studies of psychiatric conditions associated with maltreatment provide conflicting findings (Anisman & Matheson, Reference Anisman and Matheson2005; Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Holmes, Birk, Brooks, Lyons-Ruth and Pizzagalli2009; Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hariri and Williamson2015). Some studies suggest no maltreatment-related nor psychiatric-related changes in consummatory behavior, positive outcomes processing, and their related neural signaling in striatal and orbitofrontal regions (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Holmes, Birk, Brooks, Lyons-Ruth and Pizzagalli2009; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Gore-Langton, Golembo, Colvert, Williams and Sonuga-Barke2010; Pryce, Dettling, Spengler, Schnell, & Feldon, Reference Pryce, Dettling, Spengler, Schnell and Feldon2004; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas Belil, Artiges, Lemaitre, Gollier-Briant, Wolke and Paillère-Martinot2015; Ubl et al., Reference Ubl, Kuehner, Kirsch, Ruttorf, Diener and Flor2015). In contrast, other studies report a pattern of decreased neural signaling as well as reduced behavioral response to receiving reward (Gotlib et al., Reference Gotlib, Hamilton, Cooney, Singh, Henry and Joormann2010; Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Hariri and Williamson2015; Kalinichev, Easterling, & Holtzman, Reference Kalinichev, Easterling and Holtzman2001; Matthews & Robbins, Reference Matthews and Robbins2003; Willner, Reference Willner2005).

Methods

Participants

Forty-one children aged 10–15 years participated in this study: 20 with a documented experience of maltreatment (MT group) recruited via a Social Services Department and 21 with no prior Social Service contact recruited via schools/advertisements (NMT group). Exclusion criteria included the presence of a pervasive developmental disorder, neurological abnormalities, standard MRI contraindications, and an IQ below 70. Two participants from each group were excluded from the final analyses due to movement artifacts leaving a final sample of 37 children (MT group, N = 18; NMT group N = 19). Consent was obtained from the child's legal guardian, and assent to participate was obtained from all children. Procedures were approved by University College London Research Ethics Committee (0895/002). Participant details of the final sample are reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographics and psychiatric symptomatology of MT and NMT participants included in the functional magnetic resonance analyses

Note: MT, maltreated group; NMT, nonmaltreated group; SES, socioeconomic status; WASI-IQ, Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence, two IQ subscales (Wechsler, 1999); TSCC, Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children; SDQ-P, Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire—Parent report.

a Completed by caretaker.

b Composite score of self-report and parent rating of Puberty Development Scale.

c Three MT and six non-MT participants met the threshold for underresponsiveness. By excluding those individuals, the scores did not differ across the two groups.

d Missing data for 1 MT.

*p < .05.

Measures

Maltreatment history

History and severity of abuse type (neglect, emotional, sexual, and physical abuse and intimate partner violence) was provided by the child's social worker or the adoptive parent (on the basis of Social Services reports). Severity of each abuse type was rated on a scale from 0 (not present) to 4 (Table 2) in line with an established measure of maltreatment (Kaufman, Jones, Stieglitz, Vitulano, & Mannarino, Reference Kaufman, Jones, Stieglitz, Vitulano and Mannarino1994). In addition, age of onset and duration of maltreatment by subtype was estimated on the basis of the file information.

Table 2. Abuse subtype frequency, severity, estimated onset age and duration (years) in the MT group

Psychiatric symptomatology

The Trauma Symptom Checklist for Children (TSCC), a self-report measure of affective and trauma-related symptomatology was administered to all participants (Table 1; Briere, Reference Briere1996). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was completed by parents or caregiver to assess general functioning (Table 1; Goodman, Reference Goodman1997).

Cognitive ability

Cognitive functioning was assessed using two subscales of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence (Wechsler, Reference Wechsler1997).

Behavioral fMRI paradigm

A probabilistic passive avoidance task was administered in the scanner (Figure 1; White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017). Participants were required to learn what stimuli were associated with a higher chance of winning or losing points. The task consisted of two phases: a decision phase and a feedback phase. During the decision-phase participants could either (a) actively approach (by a button press) or (b) passively avoid (by withholding a response) one of four stimuli that were presented for 1500 ms. Each stimulus was presented 14 times in total (creating a total of 56 trials). The stimulus presentation was followed by a randomly jittered fixation cross (0–4000 ms). During the feedback phase one of four outcomes was presented for 1500 ms: “you win 50 points,” “you win 10 points,” “you lose 50 points,” or “you lose 10 points.” The feedback was probabilistic as the reward and punishment stimuli led to, respectively, gains and losses 70% of the time. Moreover, one reward stimulus was associated with a higher winning rate (i.e., a maximum gain of 185 points every 10 trials) while the other stimulus had a lower winning rate (a maximum gain of 70 points every 10 trials). Similarly, one punishment stimulus led to worst outcomes (a maximum loss of 185 points every 10 trials) compared to the other (a maximum loss of 70 points over 10 trials). The participants could only win or lose points if a stimulus was approached. Thus, avoidance responses led to no feedback presentation and a fixation cross was presented instead (also for 1500 ms). The feedback phase was followed by another randomly jittered fixation cross (0–4000 ms).

Figure 1. The probablilistic passive avoidance task. The figure illustrates the behavioral paradigm used in the scanner. Participants chose to either approach (via a button press) or avoid (by withholding a response) four stimuli presented one at a time. Reinforcement was probabilitstic such that over the course of the task two objects would result overall in gains and the other two in losses. (a) Following an approach response (i.e., a button press), a rewarding feedback is received. (b) Following an approach response, a punishing feedback is received. (c) Following an avoidance response (no button press), no feedback is received (i.e., no losses or gains).

The behavioral data was used to model the EV and PE for each trial for each participant based on the Rescorla–Wagner model of conditioning (O'Doherty et al., Reference O'Doherty, Hampton and Kim2007; Rescorla & Wagner, Reference Rescorla and Wagner1972). The EV for the first trial of each object was set to 0 and was then updated using the following formula:

In this formula the EV of the current trial (t) equaled the EV of the previous trial (t – 1) plus the PE of the previous trial multiplied by the learning rate (α). The learning rate was set to 0.354, calculated by taking the average across all individually estimated learning rates via a model-fitting simulation (see the online-only supplementary material for a description of the model-fitting procedure). The PE for the current trial equaled the feedback (F) of the current trial minus the EV of the current trial: PE(t) = F (t) – EV(t). These parameters were then used for the model-based fMRI analyses (described below).

fMRI data acquisition

All data were acquired on a 1.5 Tesla Siemens Avanto (Siemens Medical Systems, Erlangen, Germany) MRI scanner with a 32-channel head coil during 1 run of approximately 7 min. A total of 127 T2-weighted echo-planar volumes were acquired, covering the whole brain with the following acquisition parameters: slice thickness = 2 mm; repetition time = 85 ms; echo time = 50 ms; field of view = 192 mm × 192 mm2; 35 slices per volume, gap between slices = 1 mm; flip angle = 90°). A high-resolution, three-dimensional T1-weighted structural scan was acquired with a magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo sequence. Imaging parameters were as follows: 176 slices; slice thickness = 1 mm; gap between slices = 0.5 mm; echo time = 2730 ms; repetition time = 3.57 ms; field of view = 256 m2; matrix size = 2562; voxel size = 1 mm3.

Data analysis

Behavioral analyses

Behavioral performance on the task was assessed in relation to the number of omission errors (i.e., the number of trials in which reward stimuli were avoided) and the number of commission errors (i.e., the number of trials in which punishment stimuli were approached) as well as the total number of errors (i.e., the sum of omission and commission errors). In addition, to test the validity of the behavioral model, we examined whether the EV estimates for each trial predicted behavior (i.e., approach and avoidance responses).

fMRI analyses

Data analyses were conducted using the software package SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm8) implemented in Matlab 2015a (MathWorks Inc.).

Image preprocessing

After discarding the first three volumes of each run to allow for T1 equilibration effects, each participant's scans were realigned to the first image. Four participants (two in each group) were excluded from the final analyses due to more than 10% of the images being corrupted by head motion greater than 1.5 mm. This left a final sample of 19 NMT and 18 MT (N = 37). Data were normalized into MNI space using deformation fields from T1 scan segmentation at a voxel size of 3 mm3. The resulting images were smoothed with a 6-mm Gaussian filter and high-pass filtered at 128 Hz.

First-level analysis

Fixed-effects statics for each individual were calculated by convolving the canonical hemodynamic response function with the box-car functions modeling the four conditions: stimulus approached, stimulus avoided, reward received, and punishment received. To reduce movement-related artifacts, we included the six motion parameters as regressors and an additional regressor to model images that were corrupted due to head motion >1.5 mm and were replaced by interpolations of adjacent images (<10% of participant's data for 9 NMT and 5 MT; no difference between groups, p = .22). Furthermore, linear polynomial expansion was applied to the percent signal change at each voxel and time point using the EV and PE estimates as parametric modulators during, respectively, the decision phase and the feedback phase.

Second-level analysis

Group analyses were conducted using a series of independent samples t tests by entering the individual statistical parametric maps containing the parameter estimates of the four conditions as fixed effects and an additional “subject factor” for random effects. For the decision phase, activation in the NMT group was compared to the activation in the MT individuals for the approached stimuli modulated by the EV estimates and the avoided stimuli modulated by the EV estimates. For the feedback phase, activation in the NMT group was compared to the activation in the MT individuals in relation to the punishment feedback modulated by the PE value, and exploratory analyses were also conducted to examine the reward feedback modulated by the PE value.

Given our a priori hypotheses, small-volume corrected ROI analyses (thresholded at p < .05 corrected for family-wise error [FWE]) were performed, on the decision phase data, on the DS, VS, mOFC, and lOFC. Masks for the mOFC and lOFC were taken from the AAL atlas (WFU PickAtlas). The VS and DS masks were created based on the findings by Martinez et al. (Reference Martinez, Slifstein, Broft, Mawlawi, Chatterjee, Hwang and Laruelle2003) on the functional subdivisions of the striatum. For the punishment feedback condition, small volume-corrected ROI analyses (thresholded at p < .05, corrected for FWE) were performed in the amygdala, insula, ACC, and MCC. Masks for these regions were also taken from the AAL atlas (WFU PickAtlas).

For completeness, whole-brain analyses were also conducted, using Monte Carlo Simulation (3D ClusterSim; Ward, Reference Ward2000) correcting for multiple comparisons. Cluster-size corrected results are reported (voxelwise p < .005, ke = 75) corresponding to p = .05 FWE corrected.

Results

Behavioral results

Demographics and symptomatology

The MT and NMT groups did not statistically differ in age, gender, pubertal status, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, intelligence (IQ), and affective symptomatology (i.e., depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder; Table 1). The SDQ revealed difference among the two groups in overall functioning, and in relation to the conduct and hyperactivity scales.

Behavioral performance

The MT and NMT groups did not differ significantly in task performance at the behavioral level. In particular, they did not differ in relation to number of total (MT M = 23.22, SD = 8.39; NMT M = 23.42, SD = 6.89; t = 0.08, df = 35, p = .94), omission (MT M = 9.89, SD = 4.73; NMT M = 9.39, SD = 4.65; t = 0.33, df = 35, p = .75), and commission errors (MT M = 13.83, SD = 5.65; NMT M = 13.53, SD = 5.47; t = –0.17, df = 35, p = .87).

Model validity

To test the validity of the computational model, we examined the extent to which the estimated EV predicted participant's approach and avoidance responses. Consistent with the model, there was a significant relationship between predicted and observed behavior, average correlation: r = .23; one sample t test (null r = 0), t = 4.59, df = 36, p < .001. Moreover, the model was equally predictive of behavior across groups (t = –0.15, df = 35, p = .89).

fMRI results

Main effects in the nonmaltreated group

Whole-brain main effect analyses were performed within the NMT group in order to ensure that the four conditions (i.e., approach trials, avoidance trials, positive feedback, and negative feedback) elicited activation patterns that were comparable to previous studies. As expected, the approach and avoidance conditions activated a network that has been previously linked with EV representation and outcome anticipation (see online-only supplementary Table S.1). Similarly (although at a more lenient cluster threshold), the punishment and reward feedbacks elicited brain activity in areas associated with PE signaling (see online-only supplementary Table S.2).

Decision phase activation modulated by EV

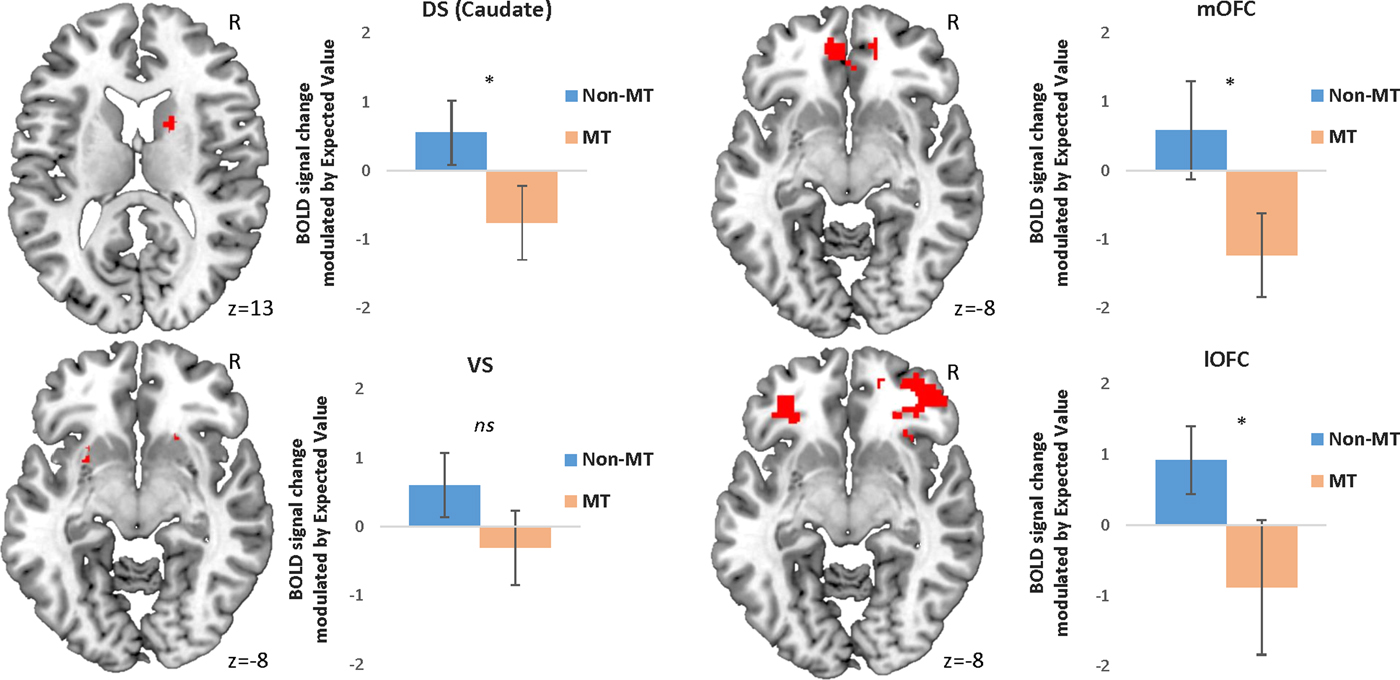

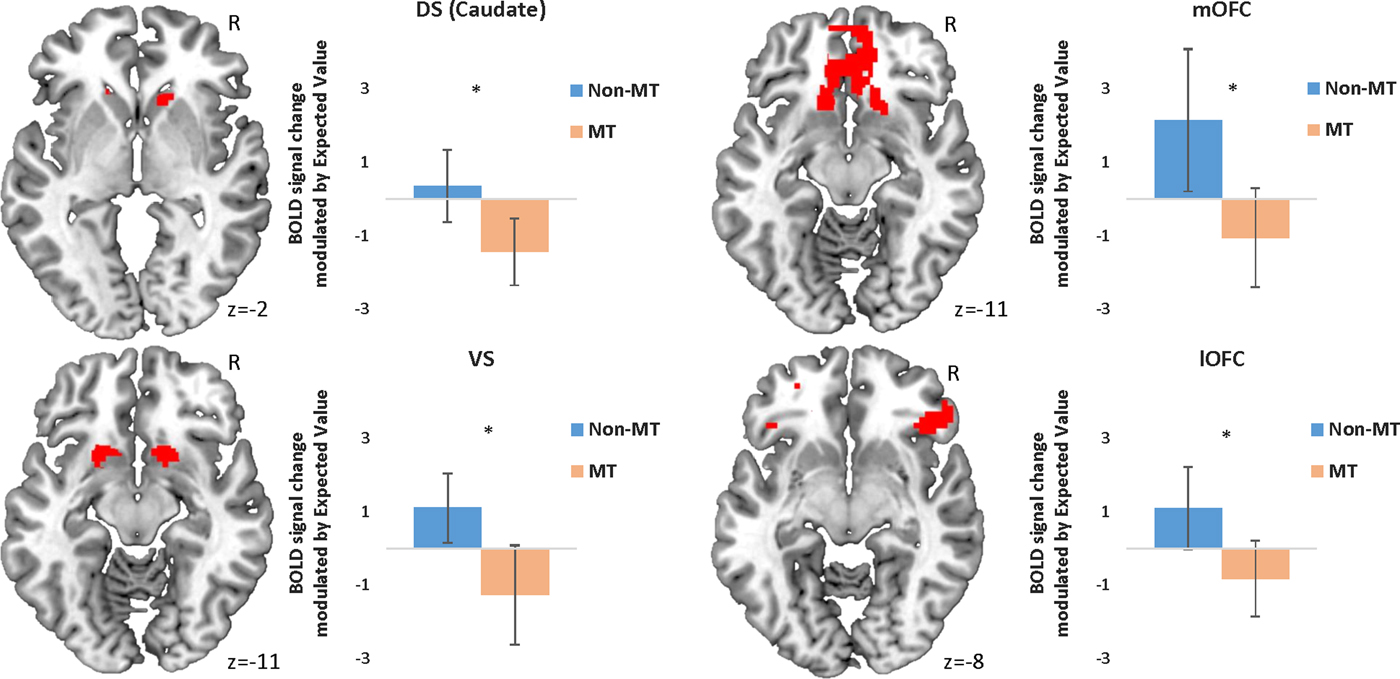

In line with our hypotheses, the MT group showed reduced modulation of BOLD activity in the DS (in particular in the caudate nucleus), the mOFC, and the lOFC as a function of EV when choosing to approach a stimulus (Table 3, Figure 2). However, contrary to our hypotheses, no statistically different activation was found in the VS (Table 3, Figure 2).

Figure 2. (Color online) Peak activation in each region of interest modulated by expected value during approach responses. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *p < .05 corrected for family-wise error. Initial threshold p < .05 uncorrected. DS, dorsal striatum; mOFC, medial orbital frontal cortex; BOLD, blood oxygen level dependent; MT, maltreatment; VS, ventral striatum; lOFC, lateral orbitofrontal cortex.

Table 3. Regions of interest demonstrating group-level differential blood oxygen level dependent responses during the task

Note: The region of interest analyses were corrected at p < .05 for family-wise error and at p < .005 for the initial threshold. R/L, right/left; ke, cluster extent; NMT, nonmaltreated group; MT, maltreated group; DS, dorsal striatum; VS, ventral striatum; mOFC, medial orbitofrontal cortex; lOFC, lateral orbitofrontal cortex.

When choosing to avoid a stimulus, the MT group showed reduced modulation of BOLD activity as a function of EV in all four ROIs (Table 3, Figure 3). Unexpectedly, the MT group also showed a pattern of increased bilateral modulation as a function of EV in the putamen (DS) when choosing to avoid a stimulus (Table 3).

Figure 3. (Color online) Peak activation in each region of interest modulated by expected value during avoidance responses. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. *p < .05 family-wise error. Initial threshold p < .05 uncorrected. DS, dorsal striatum; mOFC, medial orbital frontal cortex; BOLD, blood oxygen level dependent; MT, maltreatment; VS, ventral striatum; lOFC, lateral orbitofrontal cortex.

Findings from the whole-brain analyses (Table 4) were consistent with our ROI analyses, indicating a widespread pattern of reduced EV signaling (for both approach and avoidance responses) and also implicated other brain regions including the globus pallidus and temporal regions, such as the insula and the hippocampus (which have in some previous studies been implicated in the representation of reinforcement expectancies).

Table 4. Whole brain regions demonstrating group-level differential blood oxygen level dependent responses during the task

Note: Whole brain analyses corrected/thresholded at ke = 75, p < .005 (equivalent to p < .05 family-wise error). R/L, right/left; ke, cluster extent; NMT, nonmaltreated group; MT, maltreated group; DS, dorsal striatum; VS, ventral striatum; mOFC, medial orbitofrontal cortex; lOFC, lateral orbitofrontal cortex; dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; BA9, Brodmann area 9; MTG, middle temporal gyrus; STG, superior temporal gyrus; MTL, medial temporal lobe; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; MCC, middle cingulate cortex; PCC, posterior cingulate cortex.

The whole-brain data revealed that the MT group showed a pattern of increased activation in frontodorsal regions during EV processing for both approached and avoided stimuli (Table 4). In particular, the dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dmPFC, dlPFC; e.g., Brodmann area 9) and the dACC and MCC were implicated. These unexpected findings were interrogated further in post hoc analyses reported below.

Feedback-phase activation modulated by PE signaling

No group difference in BOLD activity as a function of PE was found during punishment feedback in the four ROIs (i.e., amygdala, insula, dACC, and MCC; Table 3). However, MCC activity modulated by PE fell just above traditional significance threshold level (p = .052, FWE). For completeness, whole-brain analyses were also conducted (Table 4). Increased BOLD response modulated by PE was found among MT individuals in regions associated with PE processing, such as the MCC (which approached significance in the ROI analyses), the thalamus, and the superior temporal gyrus (Table 4; Amiez et al., Reference Amiez, Neveu, Warrot, Petrides, Knoblauch and Procyk2013; Garrison et al., Reference Garrison, Erdeniz and Done2013). During reward feedback, no difference was found between the two groups (Table 4).

Post hoc analyses

Three sets of post hoc analyses were conducted. First, we tested whether the pattern of altered neural activation found among maltreated individuals during EV representation (Table 3) was associated with maltreatment duration and severity. These correlational analyses indicated that within the MT group, maltreatment duration was associated with reduced BOLD activity by EV in the mOFC during approach trials (r = –46, p = .03).

Second, we examined whether reduced activation in orbitostriatal regions during EV representation in the MT group (Table 3) was associated with increased psychiatric symptomatology. Previous clinical computational fMRI studies that used the same passive avoidance paradigm implemented here have found that patients with anxiety and with conduct disorder show a highly comparable neural profile to the MT group in this study during EV processing (White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017; White, Tyler, Erway, et al., Reference White, Tyler, Botkin, Erway, Thornton, Kolli and Blair2016). These clinical studies have consistently reported a pattern of reduced activation, modulated by EV, in the DS (in particular the caudate) and in the medial and lateral orbitofrontal cortices (White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017; White, Tyler, Erway, et al., Reference White, Tyler, Erway, Botkin, Kolli, Meffert and Blair2016). Thus, our correlation analyses focused on these two areas (i.e., OFC and DS). Measures of anxiety (using the TSCC anxiety subscale and the SDQ emotional problems subscale) and conduct problems (using the SDQ conduct disorder subscale) were correlated with the peak activation in the lOFC, mOFC, and DS (caudate) during EV processing within the MT group. Consistent with prior studies of EV representation with anxiety patients (White et al., Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017), reduced EV neural signaling during approach trials in the lOFC (r = –.60, p = .004) and in the DS (r = –.41, p = .04) was associated with self-reported (TSCC) anxiety symptoms levels within the MT group. Moreover, we found a significant correlation between parental-reported measures of emotional problems on the SDQ (r = –.41, p = .04) and lOFC activation during avoidance trials.

Finally, post hoc analyses were performed to interrogate the unexpected whole-brain finding of increased activity, within the MT group, in a large frontodorsal cluster during EV representation during both approach and avoidance (Table 4). One interpretation for the observed increased EV neural signaling among MT individuals in frontodorsal regions is that it represents an adaptive response, compensating for reduced signaling in areas traditionally associated with EV computations (such as the DS, VS, mOFC, lOFC, insula, and hippocampus). In line with this post hoc hypothesis, we found that MT individuals’ total error rate was negatively correlated with frontodorsal activation modulated by EV during both approach (r = –.45, p = .03) and avoidance (r = –.41, p < .05) trials. This suggests that the degree of engagement of this frontodorsal network during EV processing contributes to improved behavioral performance on the task. To explore this effect further, the total error rate was then divided into omission and commission error rates. It was found that while the BOLD response by EV in this frontodorsal cluster during both approach and avoidance trials was significantly correlated with omission errors (r = –.64, p = .002 and r = –.43, p = .04, respectively), that was not the case for the commission errors (r = –.15, p = .28 and r = –.26, p = .15, respectively).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the extent to which children with documented experiences of childhood maltreatment show alterations in the neural systems engaged with specific computations of reinforcement-based decision making. We employed a probabilistic passive avoidance task, in combination with a model-based fMRI analytic approach, in order to assess neural responses associated with EV representation and PE processing for reward and punishment cues. At the behavioral level, the children who had experienced maltreatment (MT group) did not differ from a group of nonmaltreated (NMT) peers. By contrast, at the neural level, the MT group differed from their peers in three main ways. First, the MT group demonstrated a pattern of reduced activity modulated by EV in a network commonly associated with reinforcement expectancies representation, including the orbitostriatal circuitry. Second, during losses, the MT compared to the NMT group showed increased PE signaling in frontal and temporal regions, including the mid-cingulate gyrus and the superior temporal gyrus. Third, the MT group showed increased activity in the putamen and in frontodorsal regions during EV representation.

EV modulated neural response

Reduced EV modulated neural response in corticolimbic circuitry

As predicted, maltreatment experience was associated with reduced BOLD response by EV in both approach and avoidance trials in the mOFC and the lOFC, and in the DS, especially in the caudate nucleus. Reduced response in the VS was also observed, but only in the avoidance trials. Our whole-brain analyses were consistent with these findings, and also implicated the globus pallidus, the subthalamic nucleus, insula, and the hippocampus. These regions have been previously shown to be involved in reinforcement expectancy representation in typical individuals (e.g., Bach et al., Reference Bach, Guitart-Masip, Packard, Miró, Falip, Fuentemilla and Dolan2014; Glimcher, Reference Glimcher2011; Kosson et al., Reference Kosson, Budhani, Nakic, Chen, Saad, Vythilingam and Blair2006; Zénon et al., Reference Zénon, Duclos, Carron, Witjas, Baunez, Régis and Eusebio2016); reduced neural response in these same regions has been reported in studies of psychiatric disorders associated with maltreatment experience, including anxiety, conduct disorder, and depression (Gotlib et al., Reference Gotlib, Hamilton, Cooney, Singh, Henry and Joormann2010; Ubl et al., Reference Ubl, Kuehner, Kirsch, Ruttorf, Diener and Flor2015; White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017). This pattern of reduced neural response is thought to reflect impairments in the precision of EV representation (White et al., Reference White, Pope, Sinclair, Fowler, Brislin, Williams and Blair2013, Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017). As such, the findings of the current study may reflect alterations in reinforcement-based decision making that may in turn confer increased latent vulnerability to psychiatric disorder. Our post hoc analyses, demonstrating that reduced activation in the caudate and the OFC was related to higher levels of anxiety symptomatology in the MT group, are consistent with this hypothesis. It is also noteworthy that post hoc analyses indicated a dose-dependent negative association between maltreatment duration and degree of activation in these areas, suggesting that greater maltreatment exposure was associated with more marked neurocognitive alterations.

Increased EV modulated neural response in the putamen

During EV processing for avoided stimuli, the MT group showed an unexpected pattern of increased activation relative to the NMT group in the putamen. This may initially appear surprising, given that the MT group also showed a pattern of reduced EV-related signaling in the caudate. However, studies of disorders associated with early adversity, such as depression (see Zhang, Chang, Guo, Zhang, & Wang, Reference Zhang, Chang, Guo, Zhang and Wang2013, for a meta-analysis) and anxiety (e.g., White et al., Reference White, Geraci, Lewis, Leshin, Teng, Averbeck and Blair2017), suggest that the caudate (but not the putamen) is less active during outcome anticipation. Moreover, data from a recent study investigating affect processing and regulation reported that children who have experienced maltreatment also show greater engagement of the putamen (but not the caudate) to negative cues (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015).

The putamen and the caudate are connected to different brain regions and are understood to perform different functions (Cohen & Frank, Reference Cohen and Frank2009; Grahn, Parkinson, & Owen, Reference Grahn, Parkinson and Owen2008). The caudate is thought to be crucial for EV representation, including R-O and S-O associations, flexible cognition, and it underpins goal-directed behavior (Grahn, Parkinson, & Owen, Reference Grahn, Parkinson and Owen2009). By contrast, outcome expectancy is not evaluated in the putamen. Rather, this region has been implicated in less complex and less flexible types of behavioral and cognitive representations, such as habit learning (Devan, Hong, & McDonald, Reference Devan, Hong and McDonald2011; Grahn et al., Reference Grahn, Parkinson and Owen2008). It has been suggested that the putamen may be recruited during the initial phases of reinforcement-based learning, with the caudate becoming more dominant during later stages of instrumental learning (Brovelli, Nazarian, Meunier, & Boussaoud, Reference Brovelli, Nazarian, Meunier and Boussaoud2011).

One possible explanation for the pattern of findings in the DS is that children with experience of maltreatment sustain activation of the putamen throughout the task, unlike their peers who progress to more flexible and complex reinforcement-based representations (indexed by their greater activation of the caudate and other regions involved in higher order EV processing). For maltreated individuals, it may be paramount and more adaptive to learn rapidly (at the expense of more flexible and complex EV processing) which elements in the environment are associated with punishment and should be avoided. The development of more flexible and higher order cognition in relation to reinforcement and contingency learning to negative cues may be less optimal (or even counterproductive) in environments where behavioral responses must be quickly learned to avoid punishment. Future studies are required to investigate this hypothesis by parsing out early from later stages of reinforcement-based learning differences in MT and NMT individuals.

Increased EV modulated neural response in the dorsomedial and dorsolateral frontal cortex

Our whole-brain analyses revealed a pattern of increased activation in an extended dorsofrontal network that includes the dmPFC and dlPFC prefrontal cortex (especially Brodmann Area 9), the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and also the MCC, which was unexpected, but which is in line with studies investigating outcome anticipation among depressed children and adolescents (Forbes et al., Reference Forbes, Christopher May, Siegle, Ladouceur, Ryan, Carter and Dahl2006, Reference Forbes, Hariri, Martin, Silk, Moyles, Fisher and Dahl2009). Recent neuroimaging studies of maltreatment have found that despite no differences in task performance, MT children show increased activation in dorsomedial and dorsolateral prefrontal regions while performing different cognitive functions (e.g., explicit affect regulation; McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015) and response inhibition (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Hart, Mehta, Simmons, Mirza and Rubia2015). It has been proposed that greater engagement of these regions involved in effortful control may represent a compensatory mechanism as more effort may be required for comparable task performance by children who have experienced maltreatment (McLaughlin et al., Reference McLaughlin, Peverill, Gold, Alves and Sheridan2015).

In the context of this study, the engagement of this dorsofrontal network may similarly represent an adaptive response, compensating for the reduced signaling in brain areas traditionally associated with EV representation (such as the DS, VS, mOFC, lOFC, insula, and hippocampus). In line with this potential explanation, our post hoc correlational analyses indicated that, among maltreated individuals, EV modulated activation in this dorsofrontal network was associated with improved task performance, and in particular with improvement in omission (but not commission) error rate. On this basis, we speculate that a tendency for an avoidant response in the MT group (as indexed by increased neural response to punishment) is attenuated by the increased activity found in the frontodorsal region during EV processing. If this is the case, it suggests that the comparable behavioral performance of the groups may be driven by differential neurocomputational processes.

PE-modulated neural response

PE for reward feedback

No group difference was found during PE-modulated brain activation to reward. This is in line with a large set of studies that suggests that consummatory (unlike anticipatory) neurocognitive and behavioral processes are not implicated in disorders such as depression (Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas Belil, Artiges, Lemaitre, Gollier-Briant, Wolke and Paillère-Martinot2015; Ubl et al., Reference Ubl, Kuehner, Kirsch, Ruttorf, Diener and Flor2015), nor appear associated with early adverse experiences (Dillon et al., Reference Dillon, Holmes, Birk, Brooks, Lyons-Ruth and Pizzagalli2009; Mehta et al., Reference Mehta, Gore-Langton, Golembo, Colvert, Williams and Sonuga-Barke2010; Pryce et al., Reference Pryce, Dettling, Spengler, Schnell and Feldon2004).

PE for punishment feedback

As noted earlier, extant studies on threat-detection and salience processing among maltreated children and adults have found a consistent pattern of increased activation in several regions implicated in the detection of negative cues (e.g., Dannlowski et al., Reference Dannlowski, Stuhrmann, Beutelmann, Zwanzger, Lenzen, Grotegerd and Kugel2012; McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011). On this basis, we also expected an increased pattern of PE signaling during punishment feedback in the MT group in four regions: the amygdala, insula, ACC, and MCC. However, no group differences were found in these ROIs. In contrast, the whole-brain data revealed a widespread pattern of increased activation in frontal, temporal, and subcortical areas, including the MCC, the superior temporal gyrus, the postcentral gyrus, and the thalamus. This network has been extensively implicated in PE error signaling in normative samples (Amiez et al., Reference Amiez, Neveu, Warrot, Petrides, Knoblauch and Procyk2013; Garrison et al., Reference Garrison, Erdeniz and Done2013). In addition, these findings are in line with the data from the only study that has investigated (noncomputationally) PE in maltreated children (Lim et al., Reference Lim, Hart, Mehta, Simmons, Mirza and Rubia2015). Maltreatment-related alterations in PE processing for negative information may therefore be system specific insofar as they do not overlap with the brain network that is devoted to salience detection and threat processing (e.g., insula and amygdala). Future studies should test this hypothesis by directly comparing PE and threat-detection signaling in MT and NMT individuals.

Childhood maltreatment, decision making, and latent vulnerability

As discussed above, sensitive caregiving and appropriate parental scaffolding plays an important role in the normative development of contingency detection, which is a sine qua non for the acquisition of a number of skills and higher order cognitive functions, including reinforcement-based decision making (Ellis, Reference Ellis2006; Nagai et al., Reference Nagai, Asada and Hosoda2006; Reeb-Sutherland et al., Reference Reeb-Sutherland, Levitt and Fox2012). However, this developmental learning process may be compromised by an impoverished and chaotic learning environment and by several other aspects associated with the maltreatment experience, such as unpredictable and severe forms of punishment.

It has been shown that an abusive environment can lead to the preferential diversion of attentional resources toward threat-related cues in the environment (McCrory et al., Reference McCrory, De Brito, Sebastian, Mechelli, Bird, Kelly and Viding2011; Pollak & Tolley-Schell, Reference Pollak and Tolley-Schell2003; Pollak, Vardi, Putzer Bechner, & Curtin, Reference Pollak, Vardi, Putzer Bechner and Curtin2005). Early adverse experiences may also contribute to the misattribution of negative valence to social cues in the environment that are actually neutral and nonthreatening, in line with a number of psychiatric presentations (Cooney, Atlas, Joormann, Eugène, & Gotlib, Reference Cooney, Atlas, Joormann, Eugène and Gotlib2006; Leppänen, Milders, Bell, Terriere, & Hietanen, Reference Leppänen, Milders, Bell, Terriere and Hietanen2004). Negative attention and attribution biases may, in turn, contribute to the development of abnormal EV representation in several ways: (a) by diverting away the cognitive and attentional resources necessary for normal contingency-based learning (Rogosch et al., Reference Rogosch, Dackis and Cicchetti2011); (b) by overweighting S-O and R-O associations in favor of negative information; or (c) by reducing the amount and quality of exploratory behavior, crucial for contingency learning and the development of normative EV and PE representations (Cicchetti & Doyle, Reference Cicchetti and Doyle2016; Cicchetti et al., Reference Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2006).

An alternative view is that physical and emotional neglect, common forms of childhood maltreatment (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Widom, Browne, Fergusson, Webb and Janson2009; Radford et al., Reference Radford, Corral, Bradley and Fisher2011), create aberrant environments that distort the development of flexible and contingency-based learning and context-appropriate higher order representations (e.g., Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist, & Target, Reference Fonagy, Gergely, Jurist and Target2004; Gergely & Watson, Reference Gergely, Watson and Rochat1999), leading to widespread alterations in EV and PE neural signaling. It is known that these forms of neglect are characterized by environments were primary reinforcers (e.g., food) are less predictable and frequent, and where there is a lack of timely and sensitive positive affective communication and emotional reciprocity.

The ability to envisage the consequences and predict the outcomes associated with a given stimulus or action is crucial for our ability to orient, motivate, and flexibly guide behavior toward specifics goals and navigate the environment successfully (O'Doherty et al., Reference O'Doherty, Dayan, Schultz, Deichmann, Friston and Dolan2004). However, abnormal EV representation can compromise this ability, leading to suboptimal decision making and maladaptive outcomes, as documented in a number of common psychiatric disorders (Eshel & Roiser, Reference Eshel and Roiser2010; Hartley & Phelps, Reference Hartley and Phelps2012; Stringaris et al., Reference Stringaris, Vidal-Ribas Belil, Artiges, Lemaitre, Gollier-Briant, Wolke and Paillère-Martinot2015; Zhang et al., Reference Zhang, Chang, Guo, Zhang and Wang2013). Therefore, the evidence presented here suggests that abnormalities in reinforcement-based decision making may represent a promising neurocognitive candidate system to index increased psychiatric risk among individuals who have experienced early adversity.

Limitations and conclusions

The current study has a number of limitations. First, this study has a relatively small sample size and the design is cross-sectional in nature. A longitudinal design and larger sample will be necessary to investigate whether maltreatment-related alterations found in reinforcement-based decision making are associated with future psychiatric vulnerability. A second limitation pertains to the design of the passive avoidance task employed here. Although a well-validated measure of reinforcement-based decision making used in a number of prior developmental studies of psychiatric groups, this measure does not allow the parsing of EV processing from motor-output responses during the approached trials. Future neuroimaging investigations, which require the approach (or avoidance) responses to be executed after stimulus presentation, would address this issue directly. Nevertheless, the model-based fMRI analytic approach implemented here allowed the estimated EVs (on a trial-by-trial and individual basis) to be convolved with the BOLD signal, facilitating the partialing out of the brain signal that was unrelated to the representation of reinforcement expectancies. Third, a recent study has shown that maltreatment exposure is more detrimental to the development of executive control functions when it occurs earlier (during infancy) than later in life (during childhood; Cowell, Cicchetti, Rogosch, & Toth, Reference Cowell, Cicchetti, Rogosch and Toth2015). Executive control functions, including working memory, cognitive flexibility, and inhibitory control, are central to the computations that underlie reinforcement-based learning and decision making (e.g., Ridderinkhof, van den Wildenberg, Segalowitz, & Carter, Reference Ridderinkhof, van den Wildenberg, Segalowitz and Carter2004). Therefore, an examination of the timing of maltreatment exposure may contribute to a more precise understanding of the neurocomputational mechanisms through which maltreatment interferes with the development of reinforcement-based decision making. Our post hoc analyses suggest that greater duration of maltreatment relates to more considerable neurocognitive alterations; however, the heterogeneity and sample size of the recruited sample did not allow us to systematically investigate the existence of periods during which the effect of early adversity may be particularly potent (i.e., sensitive periods; Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2004). This remains an important open question to be addressed in the future.

To conclude, this is the first study to show that childhood maltreatment may be associated with altered neurocomputational EV representation (for both punishment and reward) in a widespread corticolimbic network that includes the orbitofrontal cortex, the basal ganglia (especially the caudate), and medial temporal regions (i.e., hippocampus and insula). Moreover, in line with an account of increased neural signaling to negative stimuli and feedback in this population, an increased PE-modulated brain response during punishment trials was found in several frontal and parietal regions that have been implicated with both PE signaling and with the experiences of abuse and neglect. Consistent with the clinical literature, these neurocognitive alterations may compromise the ability of maltreated individuals to accurately predict the outcomes associated with a given stimulus or action and in turn confer increased latent vulnerability to future psychiatric disorder.

Supplementary Material

To view the supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941700133X.