1. Introduction

On 18 March 2014, 400 student protesters occupied Taiwan's Legislative Yuan. They were demonstrating against the ruling Kuomintang (KMT)'s unilateral move to force the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA) through the legislature without a clause-by-clause review. In September 2014, university students in Hong Kong called a strike in protest against the introduction of electoral reforms that would allow the Beijing authorities to screen candidates for the position of Hong Kong chief executive before a national vote.

The two student movements had much in common. Most significant was the way in which they both made use of the Internet and social media instead of traditional strategies. The movements' online news and Facebook fan pages quickly gained thousands of ‘likes’ and were shared widely on their first day of existence (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Clement and Leung2015; Lo, Reference Lo2015, 200). During the occupations of the Legislative Yuan in Taiwan and Causeway Bay and Mong Kok in Hong Kong, the protesters assigned tasks and coordinated their efforts via mobile phone apps such as Line and Facebook Messenger (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liao, Wu and Hwan2014; Lee and Chan, Reference Lee and Man Chan2016). To keep protest activities visible and accountable to the public, the occupiers even broadcasted live streams on Ustream and YouTube. The intensive use of social media in the two movements not only drew public attention to the events, but also brought their supporters out to the streets. Consequently, on 30 March 2014, 500,000 people marched in the streets of Taipei to protest against the opaque legislative procedures surrounding the CSSTA. In Admiralty, Hong Kong, between 29 September and 1 October 2014, more than 200,000 citizens joined the protests (Harbour Times, 9 October 2014).

With the emergence of new information and communication technologies (ICTs), the popularity, accessibility, and social connectability of the Internet have attracted the attention of various disciplines. Scholars and politicians have started to view the Internet as a new way of governing and bringing citizens, especially those of the younger generations, closer to the political process. Nonetheless, while most scholars would agree that the Internet has the potential to increase public access to political information, they hold conflicting views on the effectiveness of the Internet for enhancing political engagement and expanding democratic participation. Some authors suggest that the rise of new communication tools can enhance awareness of public affairs among citizens (Boogers and Voerman, Reference Boogers and Voerman2003; Best and Krueger, Reference Best and Krueger2005; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Lusoli and Ward2005), which will further encourage them to play a more active role in public life (Norris, Reference Norris2001; Ward and Vedel, Reference Ward and Vedel2006). Others worry that the Internet might lead to a reduction in real-life interactions because it encourages citizens to remain isolated in front of their computer screens (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000). Recent social media studies argue that the users tend to selectively exposure to information that confirms their preexisting political opinions (Garrett, Reference Garrett2009; Bakshy et al., Reference Bakshy, Messing and Adamic2015), and create an online environment with extreme homophily in which beliefs are amplified and reinforced by communication and interactions among like-minded users, the so-called echo chamber. Such an echo chamber might not only monger hatred and facilitate social extremism but also foster political polarization and thus erode trust in institutions and belief in democracy (Van Boven et al., Reference Van Boven, Judd and Sherman2012; Westfall et al., Reference Westfall, Van Boven, Chambers and Judd2015).

The Sunflower Movement provided a glimmer of hope for bringing young adults back to politics via the Internet, showing that the Internet not only has the potential to expand the base of youth political participation, but also might have inspired their concerns for and interests in public affairs. According to an on-site survey on the Sunflower Movement conducted by the Department of Sociology, National Taipei University, the average age of the participants was 28 and people under the age of 30 accounted for 77.2% of the total number of participants.Footnote 1

Building on previous research into online and offline political participation, this paper sets out to explore whether, how, and to what extent the Internet and social networking technologies have influenced Taiwanese citizens' political engagement from a dynamic perspective. This paper compares not only the extent of political participation among younger and older adults, but also the differences between the two age groups in terms of how the Internet influences their political engagement. This study is important for a variety of reasons. First, data on studies of civic engagement have shown a significant and consistent decline in electoral and social participation in the EU states (Blais et al., Reference Blais, Gidengil and Nevitte2004), the United States (Putnam, Reference Putnam2000; Skocpol, Reference Skocpol2004), Russia, Latin America, and East Asian countries (Chang, Reference Chang2018), particularly among young people. This trend is threatening the future of representative democracy (O'Toole et al., Reference O'Toole, Lister, Marsh, Jones and McDonagh2003). If the Internet and social media can efficiently reduce the information and transaction costs of political participation, younger citizens who possess more advanced digital skills than their elders should perceive more strongly the influence of these ICTs and are thus more likely to be mobilized through the Internet to cast their ballots.

In addition, in contrast to members of older age groups who established their patterns of political participation in the pre-Internet era, young citizens who have yet to develop stable political attitudes and value systems are much more open to the influence of the online world (Quintelier and Vissers, Reference Quintelier and Vissers2008). If the Internet can enhance government efficiency and responsiveness by providing a two-way communication channel, young citizens fluent in ICTs should be more capable of conveying their demands, expressing opinions, engaging in public debate, and turning online activities into practical political participation.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. First, I review the literature on political participation and the conflicting opinions on how the Internet influences citizens' political participation. I further highlight the research merits of the Taiwanese case and show how the Sunflower Movement might have inspired young Taiwanese adults' political participation via the Internet. In the second section, I analyze the empirical findings on political participation in Taiwan derived from the Taiwan's Election and Democracy Surveys (TEDS) from 2012, 2014, and 2016 and the 2014 Asian Barometer Survey Wave IV: Taiwan (ABS Wave IV) datasets.Footnote 2 I divide the respondents into two age cohorts: young adults and older adults, and then scrutinize the influence of the Internet on young citizens' political engagement. Although the data indicate a positive association between the use of the Internet for political purposes and young adults' political participation in the post-Sunflower Movement period, no influence was detected in the 2012 and 2016 elections. These empirical findings reflect the short-term nature of the impact of the Sunflower Movement on young citizens' political behaviors and attitudes, suggesting that the fast-changing Internet domain cannot exert a long-lasting influence on young citizens' enthusiasm for and engagement in politics. To prolong the influence of the Internet on mobilizing political participation, the paper concludes by encouraging the government to practice democracy via the Internet in order to facilitate online discussion of public affairs and enhance mutual understanding.

2. Youth, political participation, and the Internet

2.1 Life-cycle theory and youth participation

The subject of youth participation in politics has been an ongoing concern since the early 1990s (Bennett, Reference Bennett1997; Park, Reference Park, Jowell, Curtice, Park, Brook, Thomson and Bryson2000; Henn et al., Reference Henn, Weinstein and Wring2002; Kimberlee, Reference Kimberlee2002). Studies dealing with youth political engagement often treat young people as a generation apart. Not only do young citizens turn out in lower numbers to vote than older generations (Russell et al., Reference Russell, Fieldhouse, Purdam and Kalra2002), but also they are not interested in, engaged with, or concerned about politics (O'Toole et al., Reference O'Toole, Lister, Marsh, Jones and McDonagh2003), have relatively weak commitments to political parties, and are less likely than older people to be members of political organizations (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Moyser and Day1992; Park, Reference Park, Jowell, Curtice, Park, Brook, Thomson and Bryson2000; Kimberlee, Reference Kimberlee2002). This decline in the political involvement of younger generations and the decreasing levels of youth participation not only endanger the democratic representativeness of today, but also jeopardize the democracy of tomorrow.

Previous research attributes these generational differences to age (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Moyser and Day1992; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Fieldhouse, Purdam and Kalra2002). Unlike older people who have been socialized for much longer and hence have accumulated more political resources and experiences through life, young people, as newcomers to politics, are chronically politically apathetic and lack interest in and connections to politics (Parry et al., Reference Parry, Moyser and Day1992; Park, Reference Park, Jowell, Curtice, Park, Brook, Thomson and Bryson2000; Kimberlee, Reference Kimberlee2002; Henn et al., Reference Henn, Weinstein and Forrest2005). As young people become older, socialized, and educated, their own cumulative political experiences will enable them to make more informed choices with regard to electoral and political processes (Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2007, 173).

2.2 The Internet and political participation

Witnessing the dramatic growth in communication technologies and the rapid rise of online social networks such as Facebook, Twitter, Plurk, YouTube, etc., scholars have pinned their hopes on the Internet for enhancing political participation, especially among young voters (Delli Carpini, Reference Delli Carpini2000; Xenos and Foot, Reference Xenos, Foot and Lance Bennett2007). The reasoning behind these expectations consists of four elements (Strandberg, Reference Strandberg2006). First, the Internet is seen as providing opportunities for spontaneous engagement in politics, as online voting in polls, debating, blogging, and so forth all allow end users to freely express their opinions (Strandberg, Reference Strandberg2006; Ward and Vedel, Reference Ward and Vedel2006). Second, with the popularity of smartphones and other mobile devices, the diffusion of ICTs should widen the penetration rate of the Internet and further lower the entry barrier for participation in online politics (Best and Krueger, Reference Best and Krueger2005). Third, the Internet provides up-to-date information essential for participating in civic life and public discussions and a level playing field for the political opposition (Delli Carpini and Keeter, Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996; Hale et al., Reference Hale, Musso, Weare, Hage and Loader1999; Tolbert and McNeal, Reference Tolbert and McNeal2003). Last but not least, social media permit users to exchange information, ideas, and opinions of all sorts (messages, images, videos, and files), and to openly debate with other users (Barber, Reference Barber2003; Shalom, Reference Shalom2005; Soep, Reference Soep2014). The interactive nature of social media has increased the efficiency of direct democracy and facilitated relations between citizens, political parties, and politicians (West, Reference West2004; Di Gennaro and Dutton, Reference Di Gennaro and Dutton2006; Steinberg, Reference Steinberg2015, Reference Steinberg and Çoban2016). In short, social media could solve collective action problems that have long impeded the participation in mainstream politics.

Some scholars recognize the significant potential of the Internet to enhance communication both horizontally among members of the public and vertically between the public and government officials, but suspect that the Internet merely reinforces existing patterns of political engagement and thus magnifies the gap between activists and apathists (Norris, Reference Norris2001, 228; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Lusoli and Ward2005; Di Gennaro and Dutton, Reference Di Gennaro and Dutton2006, 300). They examined the Internet usage of young adults and found that the ‘disengaged’ were largely of low socioeconomic status and were less likely to interact with political sites and to visit civic webpages and further concluded that the Internet appears to exacerbate the socioeconomic biases already exhibited in civic and political participation (Vromen, Reference Vromen2003, Reference Vromen2007; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Loumakis and Bergman2003; Livingstone et al., Reference Livingstone, Bober and Helsper2004). Other scholars acknowledge the utility of social media for facilitating online political engagement and the aggregation of individuals around common causes, but question its effectiveness in creating a collective identity (Fenton and Barassi, Reference Fenton and Barassi2011; Juris, Reference Juris2012) and enhancing offline participation (Brants et al., Reference Brants, Huizenga and van Meerten1996; Streck, Reference Streck1997). Their studies show that although young people use the Internet to acquire political information more frequently, they are no more likely to vote in national elections (Bimber, Reference Bimber1998, Reference Bimber2001; Couldry et al., Reference Couldry, Livingstone and Markham2006).

Recent studies further remind us that in spite of the Internet's undeniable advantages, it is like a double-edged sword. On the one hand, social media can serve as a ‘liberation technology’ which allows people to communicate with peers about current events, gather like-minded comrades, organize protests and movements, and support political candidates and parties (Diamond, Reference Diamond, Diamond and Plattner2012). On the other hand, it might stimulate online social extremism and political polarization and thus jeopardize the foundation of democracy. Political psychologists argue that to avoid cognitive dissonance and attitudinal ambivalence, online users tend to be motivated by directional goals and selectively expose to information that simply confirms their prior views (Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006, 757; Slothuus and de Vreese, Reference Slothuus and de Vreese2010; Bakshy et al., Reference Bakshy, Messing and Adamic2015) and deliberately interact with like-minded. Such segregated information environments not only facilitate rumors, fake news, extreme attitudes, and misperception of facts (Flynn et al., Reference Flynn, Nyhan and Reifler2017; Lazer et al., Reference Lazer2018), but also monger hatred toward others and foster online cleavages (Bessi, Reference Bessi2015; Del Vicario et al., Reference Del Vicario, Vivaldo, Bessi, Zollo, Scala, Caldarelli and Quattrociocchi2016; Lazer et al., Reference Lazer2018; Stewart et al., Reference Stewart, Arif and Starbird2018).

2.3 The Sunflower Movement and its research merits

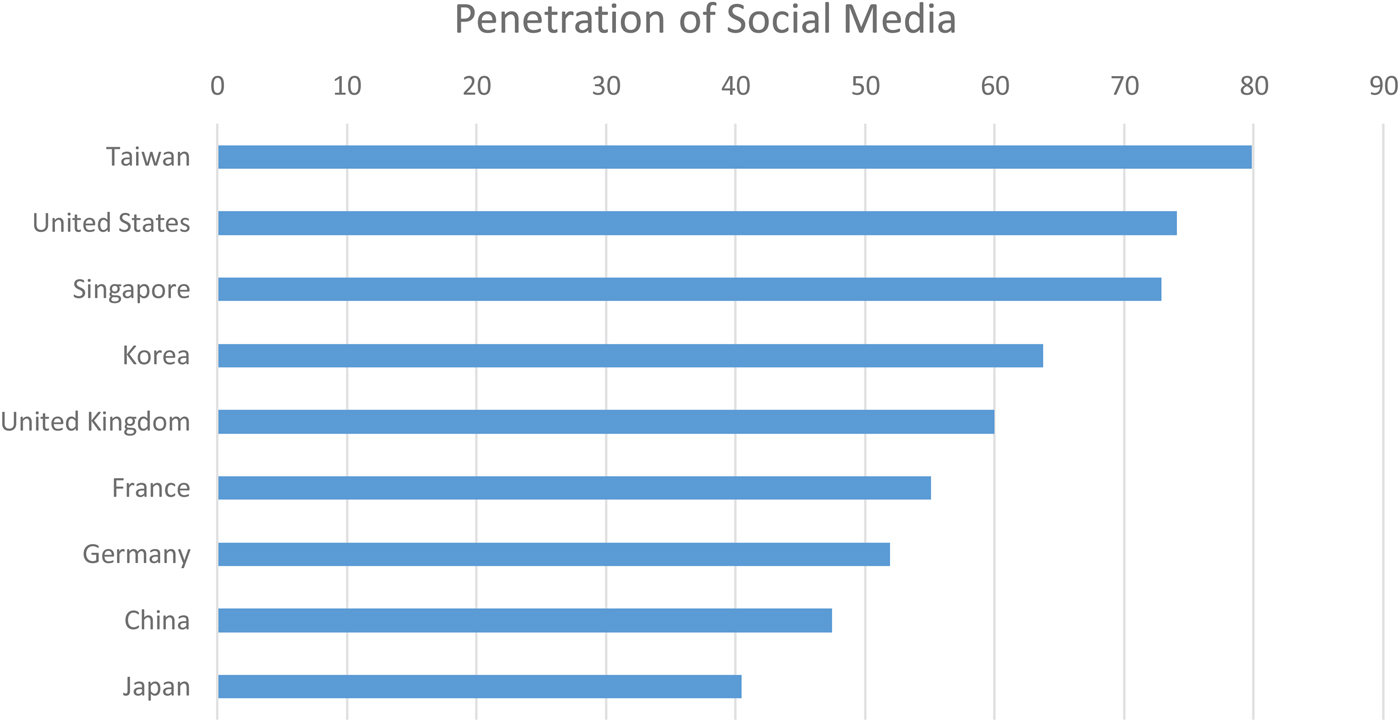

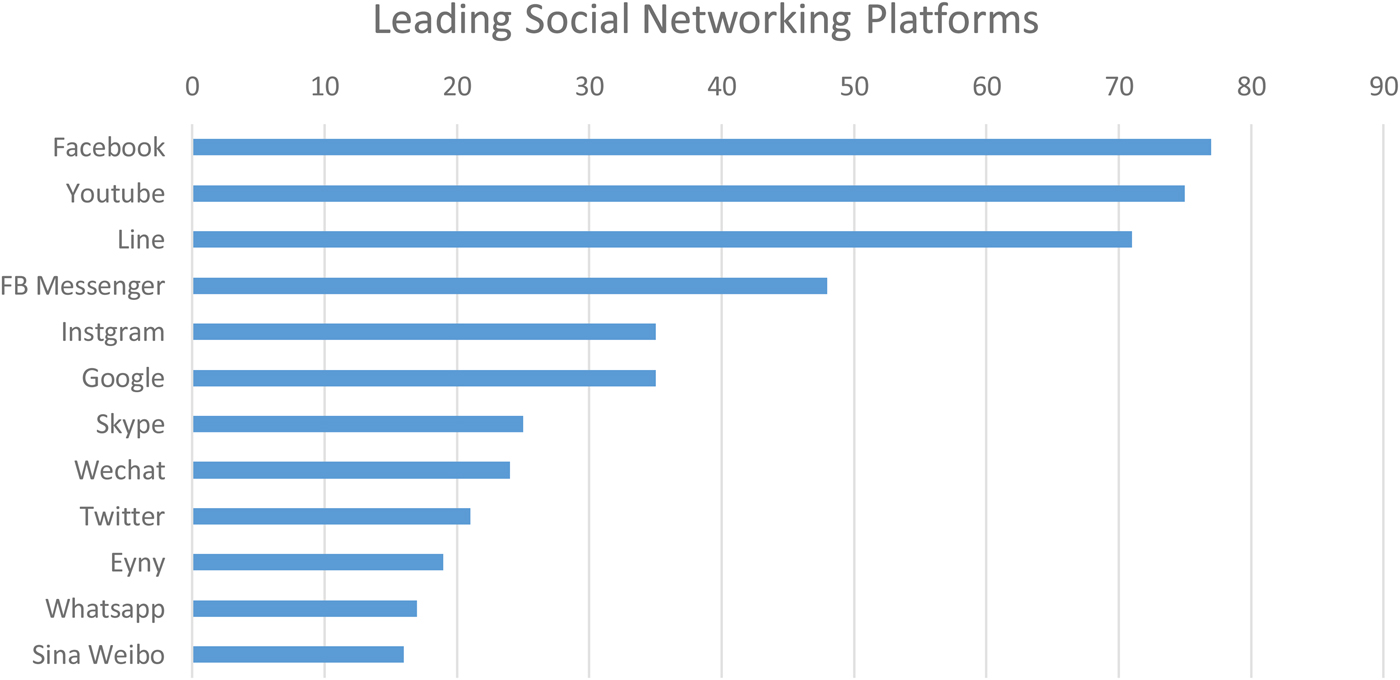

Marking the first time in which the legislature had been occupied by citizens in Taiwan, the Sunflower Student Movement showed that young Taiwanese are not uninterested in or apathetic to politics. On 17 March 2014, the KMT attempted to void the agreement with the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) and to force the CSSTA to vote for ratification in the KMT-controlled legislature. This unilateral move triggered the student occupation of the parliament the following day. From 18 March to 10 April 2014, hundreds of university students and activists occupied the Legislative Yuan to protest against the passing of the controversial CSSTA without a clause-by-clause review. Because Taiwan's media environment had been highly polarized between the incumbent KMT and the opposition DPP, at the outset of the Sunflower Movement, traditional media merely simplified the occupation as a conflict between the two camps. Therefore, to overcome the limitations of traditional media and to keep the world up to date about the constant goings-on of the movement, student occupiers waged their battles on social media platforms. Among the industrial countries listed in Figure 1, Taiwan has the highest social media penetration rate. About 80% of the population has actively used social networking services to connect with friends, share information and interests, play games and more. Figure 2 further demonstrates that Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, Line, and Google are the most popular social media platforms among Taiwanese netizens. Given the interactivity, connectability, and easy accessibility of social media, the students decided to make use of Facebook, Twitter, and other popular bulletin boards and online forums to disseminate their appeals, mobilize supporters, and challenge the mainstream media (Ho, Reference Ho2015; Lo, Reference Lo2015).

Figure 1. Social media penetration rate in industrial countries and China (Source: Statista; https://www.statista.com/).

Figure 2. Leading social networking services in Taiwan (Source: Digital in 2018 in Eastern Asia Essential Insights).

The intensive use of social media had significantly aroused public concern and anxieties over the political consequences of closer economic relations with China, with some citizens worrying that the increasing economic dependency on China might erode Taiwan's political autonomy and may result in the loss of their political liberties. On 30 March, 500,000 people rallied in the streets demanding that the CSSTA first be withdrawn from the legislature, the bill on Cross-Strait Agreement Supervision (CSAS) be enacted, the CSAS bill be legislated before the legal review of the CSSTA could take place, and a citizens' constitutional conference be convened. The Sunflower Movement thus became the last straw for President Ma and his KMT government. Ma's disapproval rating rose from 64 to 74.5% and his approval rating was down to 13.6%. On 29 November 2014, in the Taiwanese local mayors and magistrates elections held in Ma's final term, the KMT-controlled areas dropped from four municipalities and eleven counties to only one municipality and five counties. Thus began the KMT's secession of power to the DPP, culminating in the DPP candidate Tsai Ing-wen being elected and the KMT's seats in the legislature dropping from 64 to 35 in the 2016 presidential and legislative elections.

The Sunflower Student Movement stands in stark contrast to the life-cycle and motivated reasoning theories and serves as an inspiration to young people in overcoming their political apathy and lack of political efficacy by bringing them back to politics via the Internet. First of all, the life-cycle theory oversimplifies the differences in turnout rates by attributing them to generational effects. Recent studies (Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2007, 176) and the Sunflower Movement both illustrate that younger generations are no less interested in politics than their older counterparts. Second, the life-cycle theory critiques young people's lack of participation according to a very narrow conception of ‘formal' politics – i.e. politics that is concerned with the formal institutions of government, the main political parties and traditional forms of political behavior such as voting in elections (Henn et al., Reference Henn, Weinstein and Wring2002). Despite its importance in the regulation of democratic systems, voting is not the only form of political participation. Numerous recent studies and the Sunflower Movement both underscore this idea by demonstrating that new forms of participation have diverted younger generations from traditional forms of political engagement practiced by older generations (cf. Norris, Reference Norris2001; Quintelier, Reference Quintelier2007, 165).

Third, the intensive use of social media during the Sunflower Movement shows that the Internet not only has the potential to expand the base of younger citizens' political participation, but also to have inspired their concerns about and interest in public affairs and enhanced their sense of political efficacy. According to post-Sunflower Movement surveys, the percentage of young adults interested in politics increased from only 25% in 2010 to 50% in 2014 and that of young people who thought they had influence over what the government does also expanded from 34 to 50% (Data Source: TEDS 2010, ABS Wave IV). Last but not least, instead of creating an echo chamber which reinforces and amplifies the belief of its supporters by rumors, fake news, and false or dubious information, the Sunflower Movement disseminated their appeals, recruited supporters, and challenged the mainstream media by providing the most real time and transparent information from the occupied legislative floor (Lo, Reference Lo2015).

The above discussion highlights a series of important questions that emerge when studying Taiwan's political participation in the digital era. Given that we know that student activists who participated in and supported the Sunflower Movement used the Internet extensively to both coordinate among themselves and to disseminate their appeals to the public, to what extent did the Movement and the associated Internet use have a broader impact on democratic political participation? If online political information, like its offline counterpart, can encourage voter turnout (Matsusaka, Reference Matsusaka1995; Feddersen and Pesendorfer, Reference Feddersen and Pesendorfer1996, Reference Feddersen and Pesendorfer1999; Stromberg, Reference Stromberg2004), we should observe a consistent and positive association between the use of the Internet and political participation. However, if political participation was temporarily inspired by the Sunflower Movement via its intensive use of the Internet, the positive relationship between the Internet usage and political participation should only exist in the post-Sunflower Movement period, but not in other elections. The second question looks at the different impacts of the Internet on different generations. Did use of the Internet have a consistent effect on the political participation of different age groups or did it affect different generations in different ways? If online political information can inspire citizens' political participation, young adults who are more skilled at zooming from site to site, sorting, sifting and assessing online information than older citizens should be more efficient in turning their online political engagement into political participation in the real world.

Given the Internet's accessibility, interactivity, and connectability, I argue that it is hard to deny its potential in promoting political participation, especially that of young adults. However, because online behavior is often considered negligent and exaggerated, prejudice surrounding the Internet thus hinders its interactivity from the bottom up and delimits the development of online democracy. Although the Internet has widely been thought to facilitate government efficiency, considering Internet security, the representativeness of the end user, and the reliability of online information, the government rarely allows voters to officially exert their influence on policy making or hold their elected representatives accountable via ICTs. Consequently, social media often serves as a weapon of opposing activists, allowing them to disseminate their critiques on government or politicians. As shown in the Sunflower Movement, online cynicism can even bring down a government when it arouses enough sympathy. Nevertheless, it also fades away quickly and has no long-term impact when the discontent was covered by the immerse information on the Internet.

3. Political participation in Taiwan

In an attempt to answer the above questions, I used the TEDS 2012, 2014, and 2016 post-election survey data. Due to the potential impact of the Sunflower Movement on young citizens' political participation, the young adult cohort variable is created from respondents' birth year: 1974 is used as the cut-off point to divide the young adult and adult cohorts. I further divided offline political participation into two categories: electoral participation (voting turnout) and non-electoral participation (lobbying and self-help activities). This setup enables us to make an in-depth investigation into how use of the Internet and social media might differently affect different generations' political behavior instead of merely focusing on formal electoral participation.

3.1 The Internet and electoral participation in Taiwan

Figure 3 depicts the generational differences in voting turnout in recent elections in Taiwan. In line with the findings of previous studies on youth participation in politics, young Taiwanese citizens are less engaged in voting. Their average turnout rates are 10–20% lower than that of older adults. I then classify respondents into four different types along with their frequency of searching for information about elections, politics, and government on the Internet: ‘No Use,' ‘Occasional Use,' ‘Regular Use,’ and ‘Frequent Use.’ To dynamically investigate whether use of the Internet is differently associated with older and younger generations' turnout, I estimated a logit model to predict voting turnout as a function of respondents' generation, the frequency of their searching for political information online, and the interaction of the two variables. If the Internet, as suggested by previous studies, exerts greater influence on younger people than on older adult cohorts, we could expect that online political information has a greater marginal association with younger people's voter turnout than on that of older citizens across the three elections. To derive a more robust estimation, I further controlled for respondents' frequency of discussing politics (from [1] never to [4] often), gender ([1] male, [2] female), education level (from [1] illiterate to [13] graduate school), and partisanship ([0] no party affiliation and [2] with party affiliation), which have been thoroughly discussed in studies of voting behavior (see the Appendix for details).

Figure 3. Generational difference in electoral participation (Source: Chu (Reference Chu2012), Huang (Reference Huang2014, Reference Huang2016)).

Table 1 presents the results from a multivariate logit analysis of respondents' turnout in the most recent three elections in Taiwan. Since the TEDS 2014 survey did not draw on a national sample but was only conducted in the three municipalities of Taipei, Taichung, and Kaohsiung, in order to derive a more reliable comparison I also estimate samples from the municipalities in the TEDS 2012 and 2016 datasets. As shown in Table 1, the two different samples yield the similar results. The statistics in the first row of Table 1 show that the generational difference in voting engagement between younger and older adults is consistent with the findings of most youth studies and Figure 3. It reveals that, other things being equal, the younger age group was less likely to vote than older adults. The coefficients in the second and third rows respectively indicate the average marginal effect of Internet use on the older group's voting participation and the average difference in the marginal effect of Internet use on the younger and older groups' voting participation. To facilitate our understanding of the statistics, Table 2 calculates the estimated marginal effect of the Internet use on different generations' turnout rates, showing that the 2014 election stands out from the other two as the only election in which the Internet had a significantly positive association with the younger group's voting participation. Figure 4 further illustrates the predicted marginal effect of the Internet usage on different generations' turnout rates in the 2014 election and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals derived from Table 1. As depicted in the figure, as the Internet usage increases from regular use to frequent use for the younger group, the predicted turnout rate of that election increases from 85.1 to 88.7%. However, the same increase in the internet usage does not yield significant effect on older adults' voting turnout.

Figure 4. Marginal influence of Internet use on voting engagement.

Table 1 The generational difference in the marginal effects of the Internet on voting turnout

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Date Source: Chu (Reference Chu2012), Huang (Reference Huang2014, Reference Huang2016).

Table 2 Estimated marginal effect of the Internet usage on voting turnout for different generation

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

3.1.1 Non-electoral participation in Taiwan

Next is an examination of the association between Internet usage and non-electoral participation using the ABS Wave IV data, which was collected between June and September 2014, only a few short months after the Sunflower Movement. The survey asked interviewees whether they had contacted politicians, elected officials, or representatives. It also queried their experiences of participating in self-help activities, including raising issues, signing petitions, or attending demonstrations, protests, or marches for political ends (see the Appendix for details). I applied the two batteries above to generate two corresponding indicator variables, lobbying and self-help. If a respondent had practiced any of the activities above at least once in the past year, I coded the corresponding variable as 1; otherwise it was coded 0 (see the Appendix for details). Then the same interaction model was applied to estimate the association between Internet use and respondents' non-electoral participation. If the interactivity, communication feedback, and faster conveyance of information of the ICTs, as suggested by sociologists, could be used in organizing and maintaining social activities and in accomplishing e-participation (Biernacka-Ligieza, Reference Biernacka-Ligieza and Çoban2016, 112; Çoban, Reference Çoban and Çoban2016, vii), we should be able to observe that access to online political information also has a positive relationship with young citizens' participation in lobbying and self-help activities.

Table 3 shows that while control for citizens' frequency of discussing politics, gender, education levels, and partisanship, the estimated coefficient of the internet usage turns out to be insignificant. In other words, access to online political information has no association with older adults' participation in lobbying and self-help activities. In contrast to use of the Internet for political causes, citizens' offline social–political engagement and their partisanship are more significantly associated with their non-electoral participation.

Table 3 The generational difference in the marginal effects of the Internet on non-electoral participation

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Data Source: ABS Wave IV.

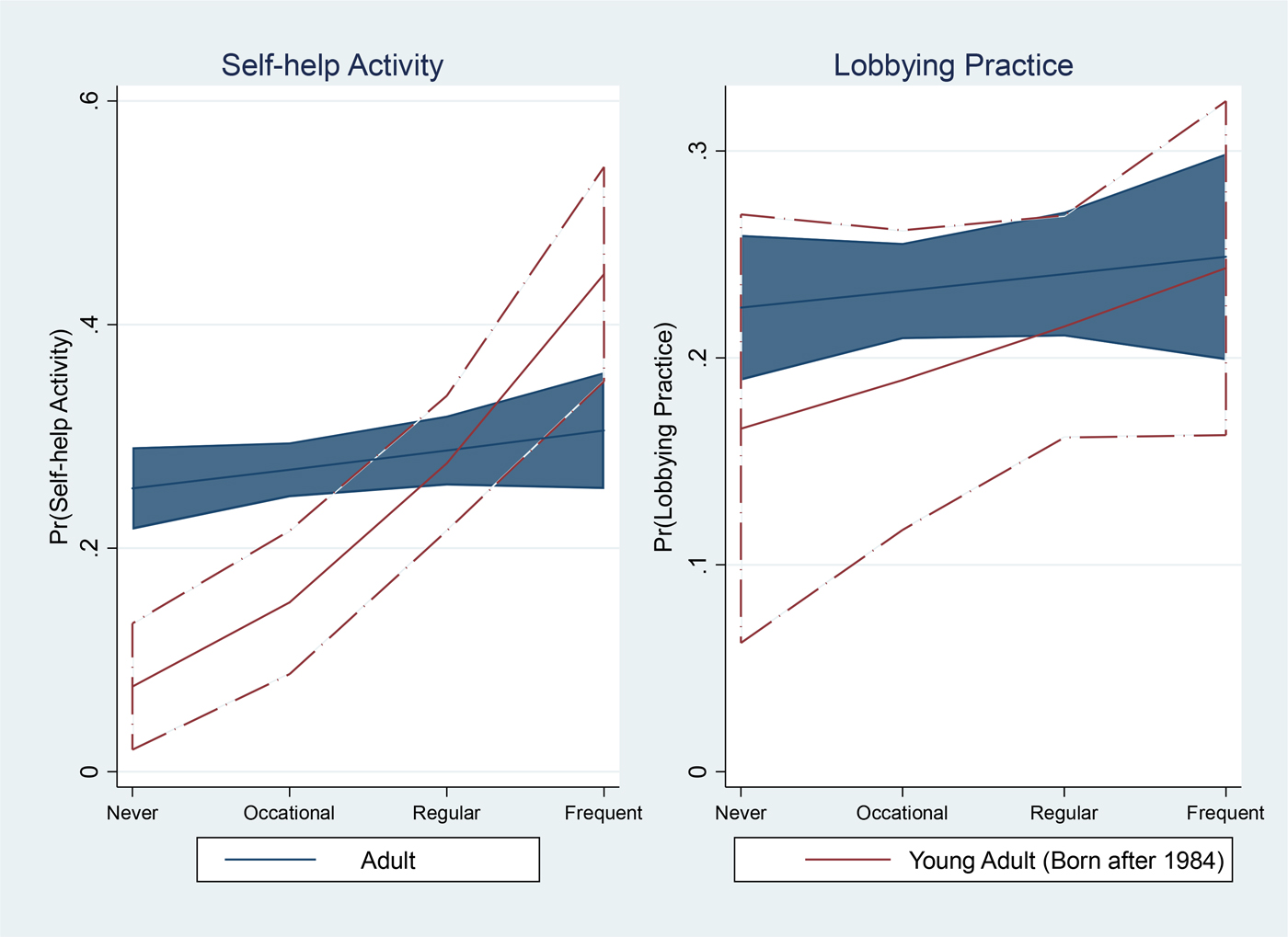

Moreover, Table 4 demonstrates that Internet usage had different associations with younger age groups' participation in different non-electoral activities. As demonstrated in Figure 5, all other things being equal, a one-unit increase in the frequency of Internet usage for political causes is significantly associated with a 3.9% increase in young adults' participation rate in self-help activities (standard error: 0.009). However, the same unit increase in Internet usage is insignificantly associated with a 0.2% increase in young citizens' participation in lobbying activities (standard error: 0.005). In other words, while the use of the Internet for political purposes has a positive association with young citizens' engagement in petitions and protests, it neither encouraged older citizens' non-electoral participation nor inspired young citizens to contact influential people.

Table 4 Estimated marginal effect of the internet usage on self help activities and lobbying practice for different generation

***p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, *p < 0.1.

Figure 5. The generational difference in the marginal effects of the Internet use on non-electoral participation.

Why did Internet usage, as demonstrated by the findings above, boost young adults' participation in electoral and self-help activities, but not inspire them to carry out lobbying activities in 2014? The Sunflower Movement was ignited by the ruling party's controversial maneuvering over the CSSTA, and the occupation of the Legislative Yuan was a sign of students' disenchantment with representative politics. Mobilized by the Internet and the Sunflower Movement, younger citizens decided to take action themselves rather than relying on conventional media, political parties, politicians, or influential celebrities.

4. Discussion: the Sunflower Movement and its influence

The above findings can be summarized as follows: first, the statistics displayed in Tables 1 and 2 indicate that it was only in the 2014 election that Internet usage significantly enhanced young adults' participation in politics. Moreover, the ABS data show that while use of the Internet inspired young citizens' participation in self-help activities, it had no significant association with their engagement in lobbying. Why do the findings derived from the data present such different stories? More precisely, why did the Internet have such an impact on young citizens' participation in the 2014 election but not in others? I assert that the findings simply reflect the event-driven nature of the Internet and the considerable influence of the Sunflower Movement.

Undoubtedly, the Internet can connect millions of people instantaneously, create new opportunities to voice opinions, and allow people to reduce the information and transaction costs associated with political participation. Nonetheless, as pointed out by Barber (Reference Barber1998, 586), ‘technology can then help democracy, but only if programmed to do so and only in terms of the paradigms and political theories that inform the program.’ Even if widely diffused, the Internet remains no more than an instrument. Its content is heavily influenced by substantive public issues that surface in discussions and debates. Unless a noticeable public event draws the attention of citizens, people mainly just use the Internet for emailing, instant messaging, shopping, online gaming, downloading files, chatting, searching for information, and maintaining personal networks. As such, the widespread perception of the Internet as an information and communication tool for assisting the offline operations of daily life actually limits its development and effectiveness. Numerous studies have shown that people only use the Internet to communicate with friends and relatives, to have fun, to release emotional stress, and to collect essential information needed for work (Shaw and Gant, Reference Shaw and Gant2002; Bessière et al., Reference Bessière, Kiesler, Kraut and Boneva2008; Kesici and Sahin, Reference Kesici and Şahin2009; Bozoglan et al., Reference Bozoglan, Demirer and Sahin2014). Since the content of the Internet was primarily designed to entertain or to enhance the quality of the offline world, it is merely a means rather than an end. Therefore, Internet users are considered to be biased and unrepresentative (Best and Krueger, Reference Best and Krueger2005). Online behavior is also viewed as inattentive and emotional. Prejudices such as these have a negative impact on the meaning and significance of online engagement. As a result, most users simply view the Internet as a virtual leisure activity or an emotional outlet and their online political activities do not necessarily mobilize them to vote in the offline world.

Throughout the Sunflower Movement, students applied social media such as Facebook, Twitter, and other popular bulletin boards and online forums to disseminate their appeals, to recruit supporters, and to challenge the mainstream media (Ho, Reference Ho2015; Lo, Reference Lo2015). While conventional media neglected the CSSTA dispute, Watchout.tw immediately wrapped up the ‘Black Box of the CSSTA for Dummies,’ demonstrating how the ruling KMT forcefully passed the disputed CSSTA without a clause-by-clause review. The information quickly acquired more than 700,000 ‘likes’ and was shared thousands of times via Facebook within just a few days. To fight against the distorted reports from the pro-government media, which prejudicially stereotyped the occupiers as mobsters, News E-Forum provided updated first-hand, real-time reports of the occupied legislative floor every 3–5 min on Facebook. Shot for Democracy even live-streamed the activities from inside the legislature, showing that the student protestors were well organized and behaved. The international department of the Sunflower Movement was responsible for translating the information of the movement into multiple languages, tracking the foreign news about the movement, and contacting foreign media and overseas Taiwanese. In short, during the Sunflower Movement, the Internet was not only used as a means to achieve certain substantive ends, it also embodied important intrinsic values of the movement, such as consensual politics, transparency, freedom and openness, which stood in stark contrast to the autocracy, nontransparency, and monopolies of conventional politics.

The intensive use of the Internet not only drew public attention to the CSSTA, but further expanded the quantity and variety of the information available on the movement, thus enhancing the visibility of the Sunflower Movement and the public understanding of the CSSTA. Some netizens spontaneously compared the extent of openness of China's market to Taiwan in the CSSTA with that of other countries such as Peru, Chile, New Zealand, and the ASEAN states. They concluded that the CSSTA, unlike how it had been described by the ruling KMT, was unfair to Taiwan. Others scrutinized the CSSTA with a clause-by-clause review and analyzed how it might seriously affect Taiwan's labor market (Hung, Reference Hung and Hung2015; Lo, Reference Lo2015). Consequently, real-time new media replaced conventional TV and newspapers as the most reliable information sources on the Sunflower Movement (Hung, Reference Hung and Hung2015; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Chang and Huang2016). While TEDS shows that only 53% of citizens acquired political information from the Internet, the on-site survey on the Sunflower Movement revealed that 86% of participants selected Internet news, Facebook, PTT, or other social media as their most important information source on the movement. Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Chang and Huang2016) further found that in contrast to the protestors who mainly obtained their information on the Sunflower Movement from TV and newspapers, those who got relevant information from social media and the Internet, on average, stayed longer hours at the protest site.

The above findings demonstrate the event-oriented characteristic of the Internet and answer why Internet use only has a positive association with young citizens' political participation in the 2014 election, but not in the 2012 or 2016 elections. Although the Sunflower Movement, as exhibited above, exerted considerable influence on its supporters, due to the fast-changing nature and the diffused content of the Internet, this effect could not last for an extended period of time after the event. In the absence of any eye-catching event such as the Sunflower Movement that could draw public attention to specific issues, the role of the Internet in the 2012 and 2016 presidential and legislative elections was more like that of the conventional media – it was being used by candidates to mobilize their supporters. Ultimately, this alone was not enough to inspire young citizens' enthusiasm for politics or further encourage their political engagement.

5. Conclusion

Two competing views exist on how the Internet influences the political process. Scholars on one side of the debate assert that the Internet can reduce various costs involved in political engagement. They emphasize the Internet's potential for enhancing political participation, including voting turnout, the voicing of concerns to governments both online and offline, and involvement in social movements and civil society. Scholars on the other side, although they acknowledge the above potentials of the Internet, suspect that the wider diffusion of Internet use might dilute its influence on patterns of political participation. Using evidence from TEDS and ABS data, this study has assessed the impact of the Internet on political engagement and sought to understand its implications for political participation. I have paid special attention to the influence of the Internet on young people, who are more skillful in searching for and utilizing online political information than their elders. The empirical data demonstrate the impact of the Sunflower Movement on the younger generations' political participation via the Internet. First, Internet usage is significantly associated with young citizens' voting engagement in the 2014 elections, but it isn't in 2012 or 2016. Second, an analysis of ABS data brings to light the public's lack of trust in government officials and elected representatives stirred up by the Sunflower Movement. The data show that although Internet use was significantly associated with young adults' participation in self-help activities, it had no impact on their participation in lobbying.

The findings above elucidate the event-oriented and instrumental nature of the Internet. Through the social connectability and widespread usage of the Internet, the KMT's unlawful legislative behavior which unilaterally forced the CSSTA through the legislature was widely shared on social media platforms and further stimulated people's dissatisfaction with Ma administration and their concerns regarding increased economic dependence on China. Nowadays, a special event such as the Sunflower Movement can quickly draw public attention, intensively mobilize its followers, and drastically impact how members of the public, especially the younger generations, view politics, potentially influencing their political behavior in short order. Nevertheless, its impact on adults is limited since most of them have established their patterns of political participation and already developed stable political attitudes in the pre-Internet era. Moreover, because the Internet is considered as biased and an unreliable source of information, the stereotype of the Internet and its end users thus delimits its influence on politics. Although top-down e-governance has become an indispensable instrument of most governments for enhancing their administrative efficiency, the bottom-up e-democracy still has rarely been implemented. As a result, the Internet oftentimes functions as an alternative approach of the opponent activists, allowing them to share photos, videos, and narratives related to the corruption of the government (Barrons, Reference Barrons2012, 57) and to archive all the crimes committed by those in power (Çoban, Reference Çoban and Çoban2016, xiii). This thus explains why the use of the Internet for political purposes was only significantly correlated with young citizens' turnout rates and self-help participation in the post-Sunflower Movement surveys. Finally, due to the fast-changing nature and the instrumental essence of the Internet, the effect of the Internet on political mobilization dissipated over time and did not last long enough to produce similar effects in subsequent elections.

How can we use the Internet to substantively facilitate political participation among younger citizens? The discussion above shows that there remains a long way to go. As discussed previously, a high Internet penetration rate only provides a prerequisite condition for participation; it does not necessarily enhance political engagement as long as incumbent governments and opposing parties still view ICTs as primarily designed to enhance their offline political ends. Therefore, to systematically remove the long-lasting instrumental stereotype of the Internet, the bias against online behaviors, and doubts about their validity, I suggest that the most efficient way to cultivate citizens' participation in politics via the Internet is to practice democracy via an online platform.

Scholars define e-democracy as a mechanism which provides novel and efficient means for citizens to exercise their influence in the policy making procedure and to hold their elected representatives accountable via ICTs (Trechsel and Mendez, Reference Trechsel and Mendez2005, 5; Macintosh, Reference Macintosh and Chen2008). Although the far-reaching feature of the Internet allows it to connect millions of people worldwide in a very short time, most political scientists suggest starting e-democracy at the local level because it opens doors for citizens interested in learning about their community and local politics and thus enhances their opportunities for engagement (De-Miguel-Molina, Reference De-Miguel-Molina2010; Cegarra-Navarro et al., Reference Cegarra-Navarro, Rodrigo, Pachón and Moreno Cegarra2012). Ellison and Hardey (Reference Ellison and Hardey2014) also suggest that social media provide opportunities to reinvigorate the public sphere of local affairs and can bridge the divide between community residents and local governments. In addition to e-democracy, there should also be initiatives to allow citizens to contribute to policy making by exchanging thoughts and opinions with other citizens via the Internet. For example, online voting on topics related to citizens' daily life, such as development schemes in their communities, would be a good start. Online schemes like these not only attract public attention to and encourage discussion of public affairs but further enhance mutual understanding between citizens. To sum up, changing how young adults engage in political life while using the Internet, and doing so in a more inclusive and democratic manner, will require more effort, moving the Internet from a mere instrument to a powerful tool.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/OHF34L.

Alex Chang is an Associate Research Scholar in the Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica (IPSAS). He received his Ph.D. in political science from the University of Iowa and joined the faculty of IPSAS in 2007. He is primarily interested in the intersection of formal models, democratic theory and quantitative analysis. He has authored and coauthored several articles published in academic journals including Journal of Democracy, Democratization, Electoral Studies, Journal of Contemporary China, Japanese Journal of Political Science, among others.

Appendix

Dependent variables

(1) Voting Turnout (TEDS)

In this presidential election on [election day] many people went to vote, while others, for various reasons, did not go to vote. Did you vote?

(0) No

(1) Yes.

(2) Non-Electoral Participation (ABS)

(A) Self-Help Activities and Lobbying Practice

Here is a list of actions that people sometimes take as citizens. For each of these, please tell me whether you, personally, have never, once, or more than once done any of these things in the past year?

(I) Self-Help Activities

(1) Got together with others to raise an issue or sign a petition

(2) Attended a demonstration or protest march

(3) Used force or violence for a political cause

(II) Lobbying Practice

(1) Contacted elected officials or legislative representatives at any level

(2) Contacted officials at higher level

(3) Contacted traditional leaders/community leaders

(4) Contacted other influential people outside the government

(5) Contacted news media

Explanatory variables

(1) Online Political Engagement

During this year's presidential and legislative election campaign, some people spent a lot of time on all kinds of media news stories about the election, while others did not have the time for this type of news. On average, how much time did you spend each day on election campaign news on the Internet?

(1) Never

(2) Occasional Use

(3) Regular Use

(4) Frequent Use

(2) Offline Social Political Engagement

When you get together with your friends, relatives or fellow workers, how often do you discuss politics?

(1) Never

(2) Rarely

(3) Sometimes

(4) Often

(3) Partisanship

Among the main political parties in our country, including the KMT, DPP, NP, PFP, and TSU, do you think of yourself as leaning toward any particular party?

(0) No

(1) Yes