Continuing professional development (CPD) is a lifelong process that involves enhancing one's knowledge, acquiring new skills and polishing existing skills. Reference Bamrah and Bhugra1 It requires psychiatrists to maintain, develop and remedy any deficits in their knowledge and skills relevant to their professional work. 2 Participation in CPD is central to maintaining standards within clinical governance and has a key role in appraisal and revalidation. 3,Reference Mynors-Wallis4 Continuing professional development is an individual exercise but for it to be effective, it needs to be carefully structured, especially in the current changing, policy-driven climate.

At the time of the surveys, the Royal College of Psychiatrists had 20 regional CPD coordinators (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/training/cpd/cpdregional.aspx) who were expected to coordinate flows of information on CPD-related matters, assisted by local trust-based CPD coordinators.

Participation in a peer group is a key element of the College CPD policy. 5 The purpose of the peer group is to review each member's personal development plan (PDP), ensure its appropriateness, and identify practical ways in which the agreed objectives can be met. At the end of the annual CPD cycle, a member of the peer group then validates the contents of the PDP on Form E, before final submission to the College. A PDP is a series of personal statements linked to the individual objectives that the psychiatrist has identified, which will help to improve the quality of care for patients that he or she provides, while at the same time ensuring that there are some personal developmental gains.

The present CPD policy has been in existence since 2001, and although the College CPD department performs a random annual audit of CPD Form E submissions, so far no survey has been published on any aspect of the existing CPD policy. Broadly speaking, the policy recommends that all CPD registrants fulfil 50 hours of CPD time annually, in a 5-year cycle. The 50 hours are comprised of 30 internal hours (usually regarded as local meetings) and 20 external hours (regional, national and international meetings). Each Form E is signed off by a member of the peer group before submission to the College's CPD department. The 5-year cycle is consistent with General Medical Council (GMC) revalidation proposals.

All consultants and staff grade, associate specialist and specialty (SASS) doctors have, by contractual rights, time available for CPD, audit, teaching, training and other such activities. This can be achieved either through the annual study leave allocation of 10 days in a full-time contract or as ‘supporting professional activities’ in the weekly timetable. The College recommends that on average one programmed activity per week is devoted to CPD and associated learning. Indeed, job descriptions are approved by the College on this basis, but once approved no monitoring is undertaken by the College to ensure that this happens. Studies on previous College CPD policies have highlighted potential difficulties in the uptake and implementation of CPD. Reference Davies and Ford6-Reference Sensky8 The main barriers are lack of protected time, lack of funding and the content of meetings being unattractive. In one study, more than a third of the sample surveyed was less impressed with locally organised meetings than with regional and national conferences. Reference Williams, Sims and Sensky7 There are inherent tensions within peer groups due to interpersonal difficulties among peers, interspecialty misunderstandings, and the conflict between the set aims and objectives of peer groups with those of the employing organisation. Reference Davies and Ford6

A key driver in the government's revalidation policy is that doctors should keep up to date with their CPD. In a small sample, Brook concluded more than two decades ago that an overwhelming number of psychiatrists disagreed that specialists should undergo recertification even though almost 96% supported the concept of CPD. Reference Brook and Wakeford9 We wanted to capture the strength of feeling among our two groups of doctors on whether or not revalidation was a valid concept for regulation of psychiatrists as well as the current status and views of the consultant psychiatrists and SASS doctors regarding their CPD and peer group activities.

Method

Survey I (regional)

A survey was conducted by distributing a questionnaire (n = 60) to psychiatrists attending a regional conference in north-west England. The questionnaire included multiple choice questions and space for free text to assess current activities and views relating to CPD and PDP. A total of 45 (75%) questionnaires were returned. Nine respondents were trainees or were consultants from other regions and were excluded. The results relating to the consultant psychiatrists from the north-west region (n = 36) are presented below.

Survey II (national)

All consultant psychiatrists and SASS doctors currently registered for CPD with the College were sent a questionnaire to determine their attitudes to CPD, peer groups and revalidation. (A copy of the questionnaire is available from the authors.)

Results

Survey I

Respondents included consultant psychiatrists from 12 National Health Service trusts (n = 34) and the independent sector (n = 2) in the north-west region (general adult 42%, child and adolescent 14%, old age 11%, forensic 8%, other 25%). The mean time as a consultant was 10 years (range 1-25). Seventy-one per cent of the consultants worked full time.

Responses on CPD requirements

All respondents were registered for CPD with the College and 83% had a current CPD certificate. Consultants experienced significantly more difficulties in meeting internal compared with external CPD requirements (39% v. 20%).

Overall, 33% of respondents had a study budget, 61% did not and 6% were unsure. On the question regarding available study funds per consultant, the answers varied from £500 to £1500 per year (28% of respondents gave the actual amount). In total, 11% admitted difficulties in getting study leave approved to attend conferences, while 42% experienced problems in obtaining financial support from their employers. Only 29% (10 of 34) of consultants said they knew their local CPD coordinator.

Responses on peer groups

Ninety-four per cent of the consultants were in a peer group and all peer groups met at least twice a year. Of the peer groups, 70% had 4-6 members, 12% had 3 members, 12% had 6-8 members, and 6% (2 groups) had 10 members. Overall, 88% of the respondents had a trust-based peer group and 73% were specialty-based. Only a minority (12%) of the peer groups included non-consultant grade doctors. Fifty-eight per cent of the consultants were willing to accept new members into their peer groups.

Survey II

A total of 6006 questionnaires were sent out. The response rate was 44% (n = 2632). Respondents who failed to indicate their grades were considered invalid for further scrutiny. Of the total, 2333 of 2358 consultants and 269 of 274 SASS doctors were valid for further analysis; 61 consultants’ replies and 39 SASS doctors’ replies were invalid, while 9 consultants’ replies and 1 SASS doctor's reply had other missing data.

The majority of consultants (93%) and SASS doctors (86.5%) were in ‘Good Standing for CPD’ with the College, which essentially is an affirmation that they had complied with College policy. However, more SASS doctors than consultants had difficulty in finding a peer group (χ2 = 113.87, d.f. = 1, P<0.001) (Table 1). Cramer's statistics is strong, so the association found is unlikely to be due to chance. Over 90% of respondents found peer groups to be supportive in achieving their CPD; 8.5% of consultants and 7.6% of SASS doctors thought that peer groups served no purpose in their CPD.

Table 1 Peer group membership

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Consultantsa | ||

| Member of peer group | ||

| Yes | 2288 | 97.4 |

| No | 61 | 2.6 |

| SASS doctorsb | ||

| Member of peer group | ||

| Yes | 234 | 85.7 |

| No | 39 | 14.3 |

Frequency of peer group meetings

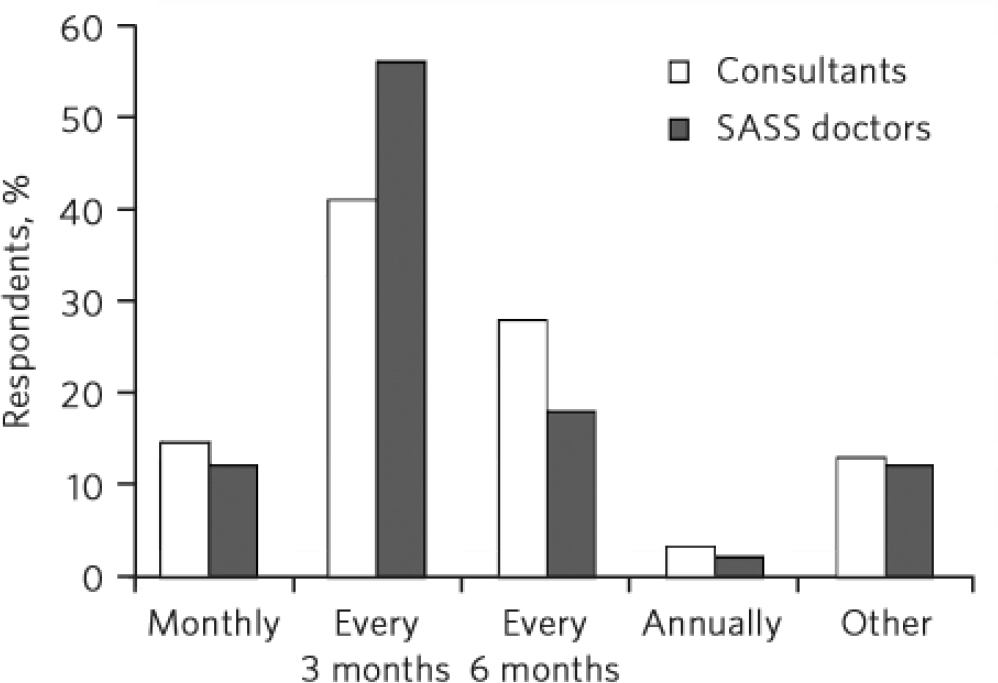

The frequency of peer group meetings is shown inFig. 1. Over 55% of consultants and nearly 70% of SASS doctors meet every 3 months or more frequently.

Fig 1 Frequency of peer group meetings. SASS, staff grade, associate specialist and specialty.

Relevance of CPD to revalidation of psychiatrists

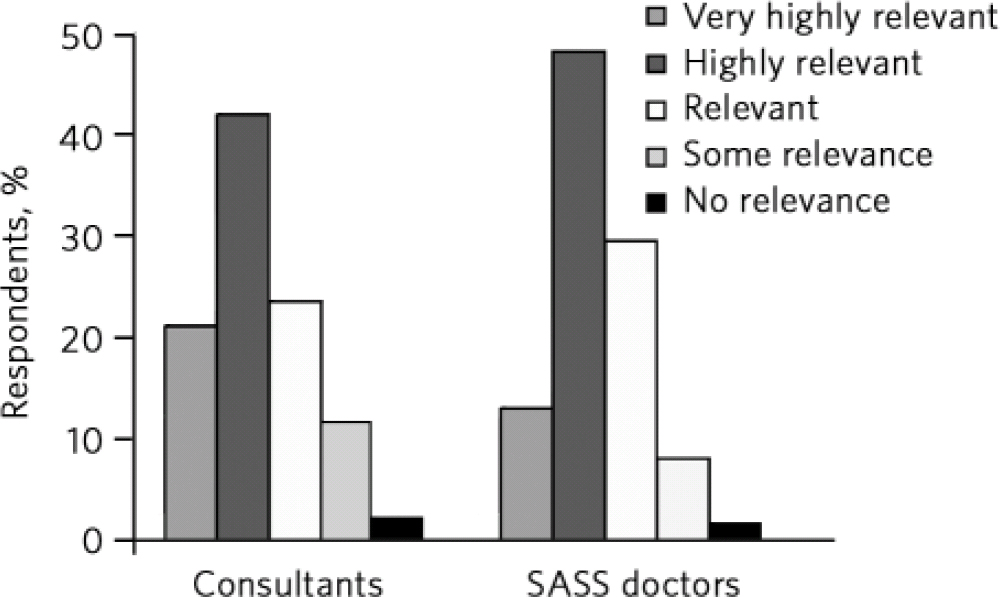

An overwhelming group of consultants (98%) and SASS doctors (98.5%) believed that CPD was very relevant to any future revalidation of their practice (Fig. 2). Only 2% (n = 51) of consultants and 1.5% (n=4) of SASS doctors considered CPD to be irrelevant to revalidation.

Fig 2 Relevance of continuing professional development to revalidation. SASS, staff grade, associate specialist and specialty.

Protected time for CPD

This survey gives a clear indication of how CPD time is available within job plans. Almost half of each group has difficulty accessing CPD time on a regular basis. For SASS doctors and consultants the inaccessibility for CPD time was quite marked in 17.2% and 9.2% of the respective samples (Table 2).

Table 2 Availability of protected time for CPD

| n | % | Cumulative % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consultantsa | |||

| Time available | |||

| Always | 246 | 10.6 | 10.6 |

| Almost always | 990 | 42.8 | 53.4 |

| Sometimes | 859 | 37.1 | 90.5 |

| Rarely | 198 | 8.6 | 99.1 |

| Never | 21 | 0.9 | 100.0 |

| SASS doctorsb | |||

| Time available | |||

| Always | 26 | 9.9 | 9.9 |

| Almost always | 116 | 44.3 | 54.2 |

| Sometimes | 75 | 28.6 | 82.8 |

| Rarely | 38 | 14.5 | 97.3 |

| Never | 7 | 2.7 | 100.0 |

Discussion

The results of both surveys show that the majority of consultant psychiatrists and SASS doctors adhere to the current College policy on CPD. The main strengths of the policy appear to be the validation by peer group activity and the submission of CPD credits, which in turn generates the annual ‘Good Standing for CPD’ certificate, which most psychiatrists seem to value.

The regional survey indicates that there is some confusion about the internal and external activities, and that many individuals have problems accessing the internal component of CPD. This might be one reason why they attended the meeting in the first place, although, as has been shown previously, consultants seem to value attendance at regional or national meetings more than attendance at local meetings. Reference Williams, Sims and Sensky7 Kerr et al surveyed 200 consultants and showed that (external) conferences ranked higher in terms of popularity than local meetings by a good margin, with visits from pharmaceutical representatives being of little educational value. Reference Kerr, Jones and Easmon10 The same study found that 94% of consultants had not been refused study leave, but that the budget was generally limited to £100-£300 per annum. Our own observation is that the budget is set between £500 and £1500 annually for some consultants, but this very much depends on the employing authority.

It is a matter of concern that many consultants experience problems in getting study leave authorised and/or securing financial support. If this reflects a general trend of restricted study leave budgets, then this might have a significant impact on the range of educational and training opportunities that consultants are able to attend in the future. The implications for other career-grade psychiatrists would be similar or worse. It is likely that consultants seek financial support from a variety of sources, such as pharmaceutical companies, research funds, lecture monies and private incomes, so the ability to attend a major conference would depend very much on the funds available.

With regard to revalidation, although we have no data to show whether psychiatrists have in the distant past supported this concept, it would appear that the attitude to recertification has softened over the past two decades since Brook demonstrated that almost 50% of his respondents either disagreed or tended to disagree with any form of recertification. Reference Brook and Wakeford9 Sensky reported 7 years later that 57% of his sample was in favour of CPD being the basis of specialist registration, Reference Sensky8 which indicates some acceptance, whereas our own national survey showed that the majority of psychiatrists (98%) support the inclusion of CPD in the current proposals on revalidation.

Our survey of 2602 members is the first indication that a significant number (almost 50%) have difficulty accessing CPD time within their job plans. The likely causes for this are competing demands of clinical work and lack of adequate funds. However, as has been demonstrated, high-quality clinical care is best delivered by those who have time for professional development and reflective thinking. Reference Bamrah and Bhugra1 Pressure of time has been cited frequently as an impediment for CPD participation, Reference Williams, Sims and Sensky7,Reference Newby11 and sadly, despite the high risks carried by psychiatrists in their day-to-day clinical work, nothing significant seems to have changed in this regard. It is clear from the CPD returns that we receive that most psychiatrists are managing to fulfil their basic requirements to remain in good standing with the College, and this is possibly through attendance at evening and weekend meetings, effectively in their own time. Our survey gives no indication of the educational worthiness of CPD activities, but one study found that 38-47% of respondents thought local meetings were generally regarded as not being as attractive as regional or national events. Reference Williams, Sims and Sensky7

We were pleasantly surprised that peer group activity was so high, particularly among consultants, although SASS doctors achieved a very respectable 85% uptake too. This is in contrast to a decade ago, when less than half of the cohort studied thought that being in peer groups was an appropriate method of undertaking their personal learning. Reference Davies and Ford6 In that study, 3 months was seen as the preferred frequency of peer group meetings, similar to our findings. A reported reason for not meeting in peer groups was lack of time, similar to our findings. The current CPD policy does not give legitimacy to time spent in peer groups, which is also a drawback.

The two surveys have a number of limitations. The brevity of the first survey contributed to the excellent response rate but limited the depth of information collected. The respondents for both surveys were a self-selected sample of CPD enthusiasts and as such participation in CPD and peer groups may be an overestimate. We would concede that some psychiatrists may not submit their returns to the College because they are registered with another Royal College (this is acceptable under reciprocal arrangements) or may maintain their own records of CPD activity without submitting them to the College. We believe that these numbers are small. Continuing professional development is a members’ privilege and therefore for the vast majority it costs nothing extra. Furthermore, the College is required under rules that govern revalidation to provide the quality assurance to the submission process that appraisers will demand.

Nonetheless, there are key issues for the College from these surveys about the reported concerns expressed by members on some of the important aspects of the policy. There is a need to review the significance of different types of CPD activity as well as the CPD infrastructure (locally, regionally and nationally) so that the College's expectation about disseminating information about new policies relating to CPD through regional structures or College divisions could be realised. In particular, the visibility or existence of trust CPD coordinators seems to be sporadic, and the distinction between external and internal CPD needs to be ironed out, with less emphasis on the strict demarcation that the policy promotes (but that has not been adhered to in recent years).

A new CPD policy has already been developed by the College's CPD Committee, with the likelihood of it being implemented in 2011. The policy strengthens the role of CPD in revalidation, gives formal recognition to peer groups, promotes distance learning and distinguishes in practical terms the domains required to become clinically effective psychiatrists. It is designed to firmly embed CPD in the job plans of every consultant and SASS doctor. However, further work needs to be undertaken on the utilisation and availability of study leave resources and the most cost-efficient and meaningful methods of learning for psychiatrists in these modern times.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks go to all the regional coordinators who have gallantly supported the College CPD policy over the past two decades, and to Professor Lindsay Thompson for her support during the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.