Introduction

Since the late 1990s, Italy has undergone a significant process of decentralisation, which has mainly resulted in the strengthening of ‘mid-level authorities’ (Vassallo, Reference Vassallo2013), and, today, it can be considered as a ‘regionally framed’ welfare system (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov2010: 60; Barberis et al., Reference Barberis, Bergmark, Minas and Kazepov2010: 377). In this context, regions, but also municipalities, have become important arenas of welfare governance and play a central role in the financing, elaboration and implementation of some social policies. Similar processes of regionalisation and decentralisation have also occurred in other European countries such as Spain, Belgium and the UK (Hooghe et al., Reference Hooghe, Marks and Schakel2010). However, changes in the territorial configuration of authority are often neglected by ‘mainstream’ literature on welfare systems, which is still heavily influenced by what has been defined as methodological nationalism (Jeffery, Reference Jeffery2008).

The aim of this article is to show that the role played by national and sub-national institutional levels in the financing of social assistance programmes may substantially vary over time and across the regions of the same country. This should be taken into account when classifying or comparing welfare systems, since the national level is not always the most important level of analysis even within the same national boundaries. Whereas some regions still significantly rely on centrally allocated funds, others may play a more active role in social spending. More generally, some regions and local authorities may have become real promoters of welfare (re)building (Moreno, Reference Moreno2011), while others may have been unable (or unwilling) to play this role. This has serious implications in contemporary welfare systems in which the concept of ‘social citizenship’ is less and less homogeneous within national borders (Greer, Reference Greer2009). Indeed, taken to the extreme, fragmentation of social rights may even undermine the territorial integrity of nation-states and national communities. In the Italian case, it seems that decentralisation of social assistance has reinforced territorial differences, which not only derive from economic inequalities but also seem linked to political and demographic characteristics of the regions.

The following section provides an overview of the academic debate on the territorial dimension of welfare policies and some hypotheses focusing on the link between socio-economic, political and demographic variables and cross-regional variation in sub-national welfare activism. I then move to describing the process of territorial reconfiguration of social policies in Italy. It is shown that, whereas spending authority in healthcare and labour market policies has almost completely and homogeneously shifted to sub-national institutions in all Italian regions, in the case of social assistance we see substantial cross-regional variation. In some regions social assistance spending is almost completely decentralised while in others it is still overwhelmingly controlled by central institutions. The empirical analysis aims to explain this variation by referring to the hypotheses presented in the theoretical framework. The main finding is that the strength of regionalist parties and female employment are positively correlated with greater direct involvement of sub-national institutions in social assistance spending. On the other hand, it seems that, in those regions with an older population, the central government plays a more relevant role. This is probably due to the ‘pension-heavy’ nature of the Italian welfare system, where more emphasis is placed on centrally allocated pension benefits than on locally administered elderly care services.

The spatial reconfiguration of welfare: context and hypotheses

The 1950s and 1960s have often been described as the ‘golden age’ of the welfare state, when the nationalisation of social protection and its massive expansion had significant implications for territorial redistribution. Keynesian territorial management introduced a variety of spatial policies intended to alleviate intra-national territorial inequalities and local authorities operated solely as the agents of (centralised) welfare state provision (Brenner, Reference Brenner, Arts, Lagendijk and van Houtum2009). However, ‘the parabola of welfare state nationalization started to slow down during the 1960s, with a renewed emphasis on local government in the sphere of social services’ (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2005: 169). Since the 1970s, decentralisation became a ‘top-down’ strategy of central authorities aimed at delegating difficult decisions, including those concerning the financing and provision of social services, to lower levels of the decision-making process (Weaver 1986; Throslund et al., 1997: 204).

The term ‘multi-level governance’ has underlined the increasing importance of territoriality in the elaboration and implementation of social and economic policies in European countries. More generally, it seems that the strengthening of sub-national and supra-national actors and institutions has significantly challenged the primacy of nation-states. The construction of the European Union has also contributed to the constraining and ‘destructuring’ of national welfare regimes but has not resulted in a recentralisation and restructuring at a higher, European level (Hooghe and Marks, Reference Hooghe and Marks2001; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2005; Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005; Greer, Reference Greer2009). Given the absence of strong institutional and political competitors at the national and supranational level, it is not so surprising that in some countries regional and municipal governments have gradually become focal points in the establishment of sub-national policy networks. Such networks may in turn play a primary role in the development of social services that better respond to the needs of local communities.

As a consequence of these important transformations, scholarly interest in the territorial politics of welfare has grown only in recent years. Greer (Reference Greer2009: 9) has argued ‘neither the comparative study of the welfare state nor the study of citizenship has been particularly friendly to territorial politics, stateless nations and federalism’. Similarly, Kazepov (Reference Kazepov2010) has suggested that ‘the territorial dimension of social policies has long been a neglected perspective in comparative social analysis’. At the same time, the literature on territorial politics has paid scarce attention to the concept of ‘social citizenship’ – despite the fact that ‘social citizenship rights are, among other things, territorial’ (Greer, Reference Greer2009: 7). One exception is the seminal work by Alber (Reference Alber1995) that, while underlining the need to go beyond ‘social transfer payments of the state’, stresses the importance of territorial dynamics in welfare systems that are increasingly service-oriented.

The study by Nicola McEwen and Luis Moreno (Reference McEwen and Moreno2005) can be considered as the first attempt to provide a systematic and comparative picture of the relationship between territorial politics and welfare development. Their study focuses on important aspects such as ‘state formation, the welfare state and nationhood, and the influence of state structure on welfare development in the light of the internal quest for decentralization and the external constraints of globalization’ (Ibid., 32). In the same year, another important book, The Boundaries of Welfare by Maurizio Ferrera, marked a breakthrough in the study of welfare and territoriality. An article by Greer (Reference Greer2010) published in the Journal of Social Policy also provided a preliminary analysis of welfare decentralisation in the US and the UK and underlined the importance of linking the study of territorial politics and welfare governance.

Therefore, this study can be placed in a recent line of analysis that has linked transformations of social governance to processes of territorial reconfiguration of authority, citizenship and solidarity in advanced democracies. However, so far the literature on territorial welfare has been mainly aimed at demonstrating that, in many post-industrial democracies, national governments no longer play a clearly dominant role in the elaboration and implementation of most social policies (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2005; Greer, Reference Greer2009; Costa-Font and Greer, 2013). At the same time, scarce attention has been paid to explaining why, within a country, some regions have been more active than others in exploiting the new opportunities derived from the spatial reconfiguration of welfare. Two general questions need to be answered: are there some social policy areas in which the role played by sub-national institutions (vis-à-vis central institutions) is not territorially homogeneous within the same country? If yes, what socio-economic, political and demographic factors explain such heterogeneity?

In a context of multi-level policy making and weakening of central standardising forces, territorial discrepancies in economic development may become a source of cross-regional inequality in the way social services are financed and administered (Costa-Font and Greer, 2013: 26). Whereas resourceful regions would be more able to develop their own policies, poor ones would still rely on the financial support of central authorities. Beramendi (Reference Beramendi2012) has even argued that decentralisation may actually be endogenous to economic inequality and may become an institutional mechanism perpetuating and reinforcing pre-existing territorial differences in the level of wealth. Additionally, as underlined by Putnam (Reference Putnam1993), the effectiveness of sub-national institutions is strongly correlated with ‘social capital’ or ‘civic culture’. The debate on how economic development and social capital are causally linked is not relevant for my argument. It is sufficient to know that they are very likely to coexist – therefore one may refer to socio-economic development – and have a combined positive effect on the ability of the sub-national authorities to actively support the development of social services. Therefore it may be hypothesised that:

H1. In a decentralised system, those regions that are more socio-economically developed will be more able to finance (and independently administer) social programmes. Poor regions will be more reliant on the support of the central government.

Sub-national political dynamics may also explain cross-regional differences in the role played by local and regional authorities in welfare development. Following the approach employed by ‘power resource’ theories (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1985; Garrett, Reference Garrett1998; Korpi and Palme, Reference Korpi and Palme2003), because of their electoral constituencies, parties that are located on the centre-left are expected to pay more attention to welfare-related policies than other parties positioned on the centre or centre-right of the political spectrum. It follows that the former may also be more active in the promotion of sub-national social programmes than the latter. The literature on regionalism and decentralisation has also underlined the fact that social democratic parties may try to set out a new level of welfare provision at the regional level that complements national welfare systems (Keating, Reference Keating2007). For instance Greer (Reference Greer2010) has suggested that in the British case decentralisation may have created new opportunities of social democratic welfare development at the sub-national level. Therefore, it may be hypothesised that:

H2. In those regions where centre-left parties are stronger, sub-national authorities will play a more active role in financing social programmes.

Yet left-wing parties emerged in a context of increasing ‘nationalisation’, ‘centralisation’ and ‘de-territorialisation’ of politics at the beginning of the twentieth century (Caramani, Reference Caramani2004), when regional differences were ironed out by strengthening cross-territorial networks of social solidarity based on class identity (Bartolini, Reference Bartolini2005: 250–251). Therefore, when the opposite process of institutional decentralisation takes place, it is less easy for centre-left parties to rely on their traditional class identity to build new systems of social protection at the sub-national level. More generally, weakening central governments and the spatial reconfiguration of politics and public policy may reduce the importance of cross-territorial competition between Left and Right, and the key role played by ‘class-based’ centre-left parties, in determining social policy outcomes.

Other political factors should therefore be considered in systems where a territorial (sub-national) dimension of welfare is emerging. Alber (Reference Alber1995: 146) has argued that, in a context of increasingly service-oriented welfare systems, party competition between Left and Right may become less important and ‘centre-periphery relations between various levels of government become a crucial dimension of social service policies’. The author clearly refers to the system of cleavages (Left-Right vs Centre-Periphery) defined by Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) as a useful framework for understanding the political dynamics affecting welfare development in more recent years. Yet he does not explicitly mention regionalist and territorial parties as important political actors in this theoretical framework.

Regionalist parties are the quintessential representatives of territorial-based politics, and literature has emphasised the important role they play in systems where ‘meso-level’ institutions have been created or strengthened (De Winter and Türstan, Reference De Winter and Türstan1998). These parties emerged from the political mobilisation of the so-called ‘centre-periphery’ cleavage, which has been defined by Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967: 14) as the competition between peripheral and central political actors. Whereas the long-term strategies of regionalist parties may range from obtaining substantial regional autonomy to campaigning for full independence from the centre, they all focus on the sub-national dimension of policy making. In particular, they are likely to challenge welfare centralism and promote a system of social protection that is less dependent on (or controlled by) national authorities. As underlined by Béland and Lecours (Reference Béland and Lecours2008), regional social policy may be used to foster sub-state solidarities and identities that in turn reinforce the centre-periphery cleavage. At the same time, ‘nationwide’ political parties in central government may have fewer incentives to channel financial resources to those regions, where their role is more marginal due to the strength of regionalist parties. Therefore:

H3. In those regions where regionalist parties are stronger, sub-national authorities will play a more active role in financing social programmes.

The emergence of new needs has also significantly changed the structure of welfare systems, which are increasingly service-oriented and focused on activating policies (Hemerijck, Reference Hemerijck2013; Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli and Natali2012). As underlined by Van Berkel (Reference Van Berkel2010), ‘countries introduced decentralisation [. . .] in order to promote service provision tailored to local and individual circumstances’ (italics added). Child care and elderly care have become important social assistance areas in societies experiencing not only ageing but also increasing women's participation in the job market. Interestingly, functional transformations in welfare systems have also required a territorial reorientation of governance. Alber (Reference Alber1995) has argued that demographic and modernisation changes have made social services ‘increasingly important ingredients of welfare state production’. This, in turn, has increased the centrality of local and regional levels of government, which have traditionally been more involved in the provision of services than in the administration of social transfers and cash benefits. According to Ferrera (Reference Ferrera2005: 174–175) ‘the twenty‐first century has [. . .] begun [. . .] with visible symptoms of a regionalization of social protection, especially of policies targeted at new social needs’ (italics added). Literature had underlined that women's labour force participation can be expected to generate pressures on certain type of services, child care in particular (Huber and Stephens, Reference Huber and Stephens2001: 47; Madama, Reference Madama2010: 201–202). Similarly, ageing is a central element of the ‘demand’ for the creation of welfare-support networks (Lucchini et al., Reference Lucchini, Sarti, Tognetti Bordogna, Brandolini, Saraceno and Schizzerotto2009), which may go well beyond traditional pension schemes and may require a more direct involvement of local service providers. One should therefore expect that:

H4. Activism of sub-national institutions is higher in regions where the new needs deriving from an ageing society or increasing women's participation in the labour market are stronger.

In conclusion, H1 refers to the effect that the ‘geography of inequality’ may have on the role of sub-national institutions in the development of social policy. H2 and H3 refer to political factors. It is suggested that, in a context of increasing territorialisation and shift from transfers to services, the traditional role of centre-left parties (H2), highlighted by power resource theories, may be less important than that of regionalist parties focusing on the centre-periphery cleavage (H3). Finally, H4 underlines the importance of territorial variation in functional pressures, coming from ageing and female employment, in explaining why some regions are more active than others in social spending.

The spatial reconfiguration of welfare in Italy

Although initially classified as a ‘conservative’ welfare system (Esping-Andersen, Reference Esping-Andersen1990), Italy has often been included in the group of ‘southern European’ or ‘Mediterranean’ welfare states characterised by high functional fragmentation (Picot, Reference Picot2012), clientelism, familism and underdeveloped social services (Saraceno, Reference Saraceno1994; Ferrera, Reference Ferrera1996; Rhodes, Reference Rhodes1997). However, in the 1970s, elements of universalism were added to the Italian model. In 1978 the insurance-based and highly fragmented health system was replaced by a national health system (Sistema Sanitario Nazionale, SSN), which was universal and taxation-based (like the British and Scandinavian systems). The construction of the Italian welfare system was also linked to processes of centralisation and ‘nationalisation’ of politics and social rights (which, however, remained functionally fragmented [Picot, Reference Picot2012]). As pointed out by Ferrera (Reference Ferrera2005: 193), ‘Italy's welfare state followed rather closely the historical parabola of “nationalisation”’ and ‘the system of national social insurance was completed and consolidated during the 1950s and 1960s’.

It may seem a paradox but the process of decentralisation started in the 1970s, that is, when the National Health System was created and the construction of a statewide welfare system was completed. Regional assemblies and governments were created in 1970 (although four special regions and two autonomous provinces had been created much earlier) but only in 1977 were they granted some (very limited) powers in the area of social assistance (Fargion, Reference Fargion1997: 97–107).

In 1992–1993 the crisis of the Italian welfare system became evident (Ferrera and Gualmini, Reference Ferrera and Gualmini2004) and the process of regionalisation and decentralisation accelerated. Regions and municipalities became important actors in the administration of social services (Ferrera, Reference Ferrera2006). With the constitutional reform ratified in 2001, sub-national levels of government were entrusted with more responsibilities in the fields of healthcare, social assistance and active labour market policies (Fargion, Reference Fargion, McEwen and Moreno2005). In the case of healthcare, all regions have clearly become primary spending actors (regardless of their socio-economic situation, demographic characteristics and policy preferences), even though they act within a national regulatory framework (Ibid., Turati, Reference Turati, Costa-Font and Greer2013). On the other hand, in the case of social assistance policies, the role played by different levels of government has not been clearly defined and this has resulted in greater (vertical and horizontal) territorial fragmentation (Kazepov, Reference Kazepov and Ascoli2011; Kazepov and Barberis, Reference Kazepov and Barberis2013). Consequently, as shown in the next section, the centre-periphery boundaries of social assistance spending change considerably across the Italian territory and this needs to be explained by looking at the institutional, socio-economic, political and demographic characteristics of the regions.

Describing the data: patterns of spending decentralisation in healthcare, labour market policy and social assistance

In this section I focus on the three policies that have been affected by decentralisation reforms in the last two decades (healthcare, social assistanceFootnote 1 and labour market policy) and I consider the share of total spending in a specific policy field directly allocated by sub-national administrations (regions and municipalities). All figures are calculated by the author on the basis of multi-level spending data taken from the dataset provided by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development and Territorial CohesionFootnote 2 . Following Costa-Font and Greer's argument that ‘no money equates to no policy’ (2013: 17), spending of regional and municipal governments as a share of total spending can be regarded as an indicator of sub-national ‘activism’ in a particular welfare area. Therefore, a larger share of total spending directly controlled by sub-national institutions means that healthcare, social assistance and labour market policies are more decentralised. A score of 0 means that spending is fully controlled by the centre, whereas a score of 100 indicates that a specific welfare area is completely and directly financed by sub-national authorities.

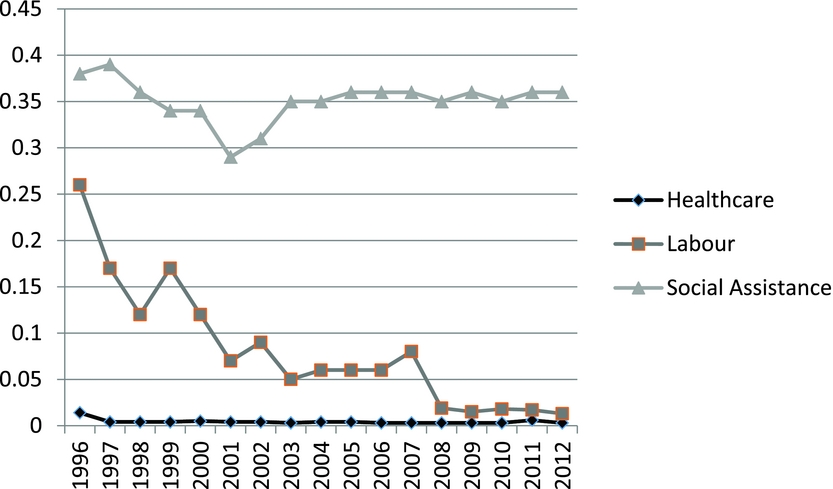

In Figure 1, the share of sub-national spending from 1996 to 2012 for each of the three policy areas is calculated as an average across the 21 Italian regions (more exactly, nineteen Regioni and two Province Autonome of Trento and Bolzano-South Tyrol). It can be noted that already by the late 1990s sub-national institutions played a central role in the financing of healthcare, approaching almost 100 per cent of the total spending. Labour market policies have also become almost totally decentralised. Interestingly, social assistance, which includes important social services such as elderly care, child care and poverty relief, seems, on average, much less decentralised than the other two policy areas. In 1996, across the 21 regions, only 20 per cent of total spending in social assistance was, on average, directly allocated by sub-national authorities and this figure has only increased to 30 per cent in 2012.

Figure 1. Share of public spending in health care, labour market policies and social assistance directly allocated by sub-national institutions (regions plus municipalities). Average across 21 Italian regions from 1996 to 2012.

However, this is just an average, which does not take into account variation across the 21 regions. In Figure 2 cross-regional variation in sub-national spending is calculated by relying on the GINI coefficient ranging from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). We can see that, across the 21 regions, variation in the sub-national share of healthcare spending has been minimal since 1996. In the case of active labour market policies it has substantially decreased to minimal levels. On the other hand, cross-regional variation in the share of social assistance spending allocated by sub-national authorities slightly declined in the late 1990s but then increased again in the early 2000s and has remained quite high.

Figure 2. Cross-regional variation in the percentage of sub-national social spending (GINI coefficient) from 1996 to 2012

Table 1 shows the radical differences existing across Italian regions in the share of sub-national spending in social assistance. It also shows to what extent such share has increased from 1996 to 2012. It can be seen that, for instance, in regions such as Aosta Valley and the Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano-South Tyrol, the share of sub-national spending has increased from 58–68 per cent of total spending in 1996 to 76–93 per cent in 2012. In other regions, local and regional authorities play a much less central role in social assistance spending. In Campania, Umbria and Molise only around 10–15 per cent of total spending in social assistance is allocated by sub-national institutions and this figure remained quite low in the period considered. In the case of Calabria the figure is even smaller than 10 per cent. On the other hand, in Friuli Venetia Giulia, Sardinia and Lombardy sub-national spending has increased to around (or more than) one third of total spending. Also Emilia Romagna and Piedmont seem to have experienced a moderate increase in sub-national social spending (above 25 per cent of total spending). Thus, whereas in the case of healthcare, and, increasingly, labour market policies we know that a sub-national dimension of welfare has clearly and homogeneously emerged across Italian regions, in the case of social assistance it is not possible to describe a general trend towards decentralisation. Some regions have strengthened their role in financing social assistance services, whereas others are still overwhelmingly, almost totally, reliant on central intervention. It is the existence of significant variation that makes social assistance an interesting policy area in the analysis of multi-level welfare governance. The following sections will try to provide an empirical explanation of cross-regional divergence by empirically testing the hypotheses presented in the theoretical part of this paper.

TABLE 1. Social assistance spending decentralisation (% of total spending directly allocated by sub-national authorities), per capita sub-national spending and central spending (1996 and 2012)

This paper focuses on sub-national spending as a percentage of total spending, since its main interest is to assess and explain activism of sub-national authorities relative to that of central authorities. This can be also defined as ‘spending decentralisation’. However, one could also consider the absolute level of generosity of social assistance spending at the sub-national level calculated as per capita sub-national spending. There is a strong correlation (r=0.89) between the two measures. Table 1 also suggests that, in some regions, sub-national per-capita spending has increased at faster rates than central spending, thus resulting in a more marked increase in spending decentralisation. At the end of the quantitative analysis presented in the next section, an additional model will be included to see if there has been a ‘replacement effect’ between sub-national and central per capita spending.

Multivariate model

As already mentioned, the quantitative analysis of this paper relies on time-series, cross-sectional data referring to sub-national spending in 21 regions (the two Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano-South Tyrol are analysed separately) as a share of total social assistance spending (subnational plus central) over a period from 1996 to 2012. Given the longitudinal nature of the data, the multivariate model presented in this section is built by following Beck and Katz's (1995) recommended procedure using panel-corrected standard errors (PCSEs), corrections for first-order autocorrelation, and imposition of a common rho. This technique is also used by Huber and Stephens (Reference Huber and Stephens2001) in their seminal work on the development and crisis of welfare states.

Before moving to the analysis of the results, the independent variables included in the model are presented (descriptive statistics are also provided in the Appendix). The level of socio-economic development is measured by using per capita GDP. This value can be used as a proxy of socio-economic development. In Italian regions per capita GDP is also strongly correlated to various indicators of ‘social capital’ proposed by Putnam (Reference Putnam1993). Additionally, GDP per capita is strongly and positively associated with the fiscal capacity of the regions (r=0.91), that is, with the amount of revenues deriving from direct regional taxationFootnote 3 . Therefore rich regions rely on a larger amount of autonomous resources which, as expected by Hypothesis 1, could be used to increase their autonomy from central government.

Strength of the Left is measured by considering the share of regional council seats won by centre-left parties in the regional councilsFootnote 4 . There is evidence that this operationalised variable is also strongly correlated with left-wing representation in municipal councils and can therefore be used as a proxy of the latter variableFootnote 5 . At the same time, regional councils provide a better picture of sub-national political equilibria than municipal councils, where ‘local lists’, which are not formally partisan, cannot always be easily classified by referring to left-right politics (Vampa, Reference Vampa2016). Lastly, sub-national spending data used for the dependent variable are aggregated regionally by the Ministry, suggesting that municipalities are embedded in a regional social system where regional institutions provide the legislative/regulative framework and set spending priorities. Similarly, I consider the share of seats won by regionalist partiesFootnote 6 to test the third hypothesis. Italy is a good case study to test both political hypotheses. Indeed in this country it is possible to find some regions in which left-wing parties have been traditionally strong (Trigilia Reference Trigilia1986; Floridia, Reference Floridia2010) and other regions, which have witnessed the emergence and strengthening of regionalist and ethnic parties (Giordano, Reference Giordano2000; Tambini, Reference Tambini2001; Caramani and Mény, Reference Caramani, Mény, Peter Lang, Costa-Font and Greer2005; Massetti and Sandri, Reference Massetti and Sandri2012).

The ‘ageing’ variable is most effectively measured by considering the percentage of the regional population aged 65 and above. The percentage of women aged between 15 and 64, who are employed, is used as an indicator of female participation in the workforce.

Lastly, differences in formal regional powers should be taken into account. Indeed, in Italy, regions have been traditionally divided into two broad categories: ordinary and special statusFootnote 7 . The Regional Authority Index (RAI) developed by Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Schakel2010) measures policy making, administrative and fiscal autonomy of the regions on a scale from 0 (no autonomy) to 24 (full autonomy). This indicator is included in the multivariate analysis as a control variable.

In Model 1 (Table 2) there are four statistically significant (at 0.01 level) coefficients: regionalist parties, ageing, female employment and the control variable, institutional special status. The coefficient of regionalist parties suggests that if in a region these parties obtain, for example, 10 per cent of the seats in the council, the share of social spending directly allocated by sub-national authorities is expected to be six percentage points higher than in a region where regionalist parties have no representation, controlling for the other variables. On the other hand, the coefficient of left-wing parties is negative, although not statistically significant. In those regions where centre-left parties are stronger, the level of activism of sub-national institutions in social assistance spending is not significantly different from those in which they are weaker. This means that power-resource theories focusing on the strength of the left have little explanatory power in multi-level settings, where the mobilisation of regionalist parties (regardless of their position on the left-right axis) seems to play a much more important role. Therefore, left-right party competition becomes less important than the rokkanian ‘centre-periphery’ cleavage. In Italy the latter aspect of competition is closely linked to the well-known ‘North-South’ territorial divide, which has become increasingly salient since the 1990s (Fargion, Reference Fargion, McEwen and Moreno2005) and has resulted in the electoral success of new regionalist parties (the Northern League in particular).

TABLE 2. Explaining cross-regional variation in spending activism of sub-national authorities from 1996 to 2012 (social assistance)

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05;***p < 0.01. Standard error in brackets.

Interestingly, the coefficients of ageing and female employment do not have the same direction. Whereas the former is negative, indicating that the larger the share of people aged above 65, the lower the share of sub-national social spending in social assistance, the latter is positive, suggesting an opposite relationship. An explanation for this is that, in the Italian context, old people mainly benefit from pension schemes, which are still centrally allocated, rather than from social assistance services. Italy has often been classified as having a ‘pension-heavy welfare system’ (Fargion, Reference Fargion, McEwen and Moreno2005; Bibbee, Reference Bibbee2007; Blome et al., Reference Blome, Beck and Alber2009), in which pension schemes have often replaced social services (like elderly care) as a source of social protection for old people. For this reason, an ageing population does not lead to increasing involvement of local and regional institutions in social assistance spending.

On the other hand, central transfers to families are relatively low in the Italian system and family policies and services (in particular child care) are almost completely managed by sub-national institutions. This explains the positive (and statistically significant) coefficient of female employment. Yet, interpreting the importance of female employment in causal terms is quite problematic. As underlined by Madama (Reference Madama2010: 201–202), higher female employment may indeed produce a stronger demand for social services but, at the same time, may be the consequence of well-functioning and extensive social services (Del Boca and Rosina, Reference Del Boca and Rosina2009). Additionally, female employment is strongly correlated with per capita GDP (r=0.9), thus creating problems of multicollinearity. For this reason, in Model 2 I have excluded female employment. As expected, the GDP coefficient increases its magnitude and becomes statistically significant at 0.01 level. Richer regions also have a more developed sub-national dimension of social assistance.

As highlighted by neo-institutionalist literature (Pierson Reference Pierson1994), developments in social policy – particularly changes in social spending – do not occur in a vacuum but depend on pre-existing conditions. Therefore, in Model 3, I have also included a lagged dependent variable to capture ‘dynamic effects’ (Keele and Kelly, Reference Keele and Kelly2006) and take into account the fact that spending in time ‘t’ is a function of spending in ‘t-1’. Yet the results of Models 3 and 4 should be interpreted with caution. Indeed, other scholars (Achen, Reference Achen2000; Kristensen and Wawro, Reference Kristensen and Wawro2003) have underlined that this model specification may bias other coefficients towards negligible values, while artificially inflating the effect of the lagged dependent variable.

Even after adding a lagged dependent variable, some of the results obtained in Models 1 and 2 are confirmed. Notably, in Model 3 (Table 2) the coefficients of regionalist parties’ strength and ageing population remain statistically significant at 0.05. Of course, their magnitude is much smaller because a large part of their effects is absorbed by the lagged dependent variable which is, as expected, statistically significant at any conventional level. The effect of special autonomy clearly collapses and loses statistical significance, probably as a consequence of the very conservative estimation produced by including a lagged dependent variable, which captures some institutional characteristics of the regions. Again, including or excluding the female employment variable, which is no longer statistically significant, makes a difference for the socio-economic variable (per capita GDP) in terms of magnitude and statistical significance. It should also be noted that the already high R-squared in Models 1 and 2 (0.70 and 0.69) becomes even higher in Models 3 and 4 (0.96), meaning that – and this is not really surprising – including a lagged dependent variable significantly improves the fit of the mode.

It should also be underlined that Aosta Valley, South Tyrol-Bolzano and Trento have very high values of decentralised spending compared to the other regions. Their social assistance spending may be higher because of their different arrangements in the provision of invalidity pensions (pensioni di invalidità). The Ministry database only provides aggregate figures and it is not possible to assess to what extent region-specific arrangements affect the level of spending decentralisation in the three regions. Including a lagged dependent variable in Model 4 already provided an important robustness check, since it gave us an idea of the ‘pure’ effect of each independent variable, regardless of the level of spending decentralisation at the beginning of the time series (thus reflecting different institutional arrangements that were already in place in the late 1990s).

Another way to check whether the general results of this analysis are valid would be to exclude the three ‘extreme’ cases from the model. Results of this last robustness check are shown in Model 5. It can be seen that excluding Aosta Valley, South Tyrol-Bolzano and Trento, the importance of per capita GDP increases, whereas the effects of ageing and female employment become insignificant. The effect of regionalist parties is still statistically significant (at the 0.1 level) and this further confirms the importance of ‘centre-periphery’ politics, even if the three regions in which regionalist parties have been considerably stronger have been excluded from the analysis. Lastly, the negative effect of left-wing mobilisation becomes significant at the 0.05 level. Surprisingly, regions dominated by left-wing parties have been less active than other regions in social spending, controlling for all the other variables.

So far the dependent variable of the multivariate model has been sub-national spending as a percentage of total spending. However, as underlined in the previous section, one may also consider absolute per capita spending and see whether the socio-economic, political and demographic factors considered here also affect this variable. Additionally, it would be interesting to see to what extent the increase in the sub-national per capita spending is influenced by decreasing central spending (replacement effect). The preliminary analysis in Table 3 (Model 1) suggests that such replacement effect does not exist since the coefficient of per capita central spending is negative but not statistically significant (and even positive and statistically significant in Model 2). Per capita sub-national spending is positively affected by the strength of regionalist parties, female employment and formal institutional asymmetries. On the other hand, ageing still has a negative effect on sub-national spending and strength of centre-left parties does not have any significant effect. The only result that deviates from the previous models is that of per capita GDP, which has a negative and significant (at 0.05 level) effect on per capita spending. Further research, relying also on qualitative analysis, is needed in order to better explain this surprising result. At this stage, it may be suggested that wealthier regions have been able to build a more autonomous (Table 2, Models 2, 4 and 5) but less generous (Table 3, Model 1) system of social governance. The positive effect of regionalist party and female employment is confirmed in Model 2 (Table 3), after excluding the three most generous regions: Aosta Valley, Bolzano-South Tyrol and Trento.

TABLE 3. Explaining cross-regional variation in per capita sub-national spending from 1996 to 2012 (social assistance)

*p<0.1; **p<0.05;***p<0.01. Standard error in brackets.

Conclusion

Unlike healthcare and labour market policy, social assistance is not homogeneously decentralised across the Italian territory. As shown by the data provided in this paper, whereas in some regions sub-national institutions play a more important (sometimes clearly dominant) role in social assistance spending, others still overwhelmingly rely on resources directly allocated by the central government. This points to the fact that it is not always possible to focus on just one level of analysis – either national or sub-national – when studying welfare policies.

Variation in social assistance decentralisation is only partly explained by formal institutional asymmetries (i.e. the distinction between ordinary and special status regions). Indeed, it seems that today, in those regions where regionalist parties have been stronger, sub-national authorities have come to control a significantly larger amount of spending on social assistance than those in other regions. On the contrary, and quite surprisingly, variation in the strength of left-wing parties does not seem to have a significant effect. These findings suggest that, in increasingly multi-level systems, the centre-periphery political cleavage may play a much more important role in explaining sub-state welfare development than traditional competition between Left and Right. This means that in a context of ‘de-nationalisation’ of social policy, territoriality rather than class may become a crucial political factor in welfare dynamics. This aspect is rarely considered by power resource theories and future studies should empirically test the importance of territorial political cleavages in other European (or non-European) countries.

Another interesting finding is that whereas female employment seems to have positively affected the decentralisation of social policy spending, since sub-national institutions often provide child care and family services, ageing on the other hand is negatively associated with the dependent variable. This is because a pension-heavy system, like the Italian one, has relied more on centrally allocated pensions than on services for the elderly. Lastly, female employment is highly correlated with socio-economic development and, once it is removed from the model, it becomes clearer that wealthy regions have been more able than poor ones to build a more autonomous system of social assistance (although not very generous, as shown in Table 3).

There are of course some limitations in the analysis presented here. It seems that regionalist parties have played an important role in the development of a regional social dimension in Italy. Their role is definitely more important than that of centre-left parties, which are traditionally regarded as the main driving force of welfare building. However, future studies should shed more light on how the centre-periphery cleavage, on which regionalist parties focus, is also shaped by vertical ‘fiscal games’ and fiscal constraints. Unfortunately, additional hypotheses referring to this, rather promising, stream of investigation could not be tested due to the lack of systematic quantitative data at this stage. Also some qualitative case studies may add some complexity to the quantitative model and show whether and how central and peripheral actors use fiscal tools to advance their (often contrasting) political projects.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Luis Moreno and Francisco Javier Moreno-Fuentes, as well as two anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Social Policy, for their constructive remarks and suggestions on an earlier draft of this manuscript.

Appendix

Descriptive statistics of independent variables