INTRODUCTION

Warfare as a process profoundly impacts the human experience. The fortification of settlements in many parts of the world defined ancient notions of culture, community, and wilderness (Ballmer et al. Reference Ballmer, Fernández-Götz and Mielke2018; Tracy Reference Tracy2000). The creation and maintenance of martial landscapes can provide a means for social differentiation, which includes the perpetuation of social hierarchies (Johnson Reference Johnson2002; Müth et al. Reference Müth, Schneider, Schnelle and De Staebler2016). To better understand the relationship between war and institutionalized social inequality, I examine how the tactic of defense-in-depth was implemented at the site of Tzunun, Chiapas, Mexico.

Researchers have long debated the link between social conflict and inequality. In the contemporary world, it is evident that colonialism and neocolonialism have been made possible in large part by military might (e.g., Fanon Reference Fanon1968; Giddens Reference Giddens1985; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2009). War-making can lead to the domination of others and at least the threat of martial force can be used to open new avenues for capital accumulation (Foucault Reference Foucault2003; Murphy Reference Murphy2003; Tilly Reference Tilly, Tilly, Evans, Rueschemeyer and Skocpol1985). Given the interconnections between war, power, and political economy, investigators have sought to understand if similar relationships existed in the past and in non-Western cultures (Earle Reference Earle1997; Flannery and Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2012; Junker Reference Junker1999; Kirch Reference Kirch1994; Otto et al. Reference Otto, Thrane and Vandkilde2006). The ability of archaeologists to understand war, however, tends to be constrained by what Kim and Kissel (Reference Kim and Kissel2018:2) term the “literary horizon,” which refers to the differential constraints posed on archaeological analysis due to the availability of written records.

For many societies that were documented by literate peoples, much is known about the practice of war. Military historians have debated issues such as command structure, battle order, combat techniques, and actions in particular campaigns among the ancient Egyptians, Classical Greeks, and during the warring states period of China (Anglim et al. Reference Anglim, Rice, Jestice, Rusch and Serrati2002; Goldsworthy Reference Goldsworthy2005; Keegan Reference Keegan1993; Lynn Reference Lynn2003; Matthew Reference Matthew2012; Sidebottom Reference Sidebottom2004; Spalinger Reference Spalinger2005). Scholars of ancient Rome can question why Varus led his armed forces into the Teutoberg Forest, the tactics in the Battle of the Teutoberg Forest, and the ramifications of the resulting disastrous defeat for the Roman Empire (Clunn Reference Clunn2009; Murdoch Reference Murdoch2008; Wells Reference Wells2003). Once researchers cross the literary horizon, however, martial practice becomes more opaque and investigators tend to rely on presence/absence arguments to understand war in the human experience.

The presence of fortifications, weapons, martial iconography, skeletal trauma, burning/destruction, or preferably some combination of these factors is used by archaeologists to make claims about warfare in the past (Allen and Jones Reference Allen and Jones2014; Arkush and Allen Reference Arkush and Allen2006; Carman and Harding Reference Carman and Harding2009; Clark and Bamforth Reference Clark and Bamforth2018; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kusimba and Keeley2015; LeBlanc Reference LeBlanc1999; Milner Reference Milner1999; Sherman et al. Reference Sherman, Balkansky, Spencer and Nicholls2010). Yet, an interpretive gap exists between finding material indicators of war and documenting the existence of inequality in a context under investigation. Beyond establishing a correlation, how can scholars tangibly connect social processes and material remains to demonstrate that war directly contributes to the institutionalization of inequality?

Like other areas of the world, Maya historical archaeology can provide some of the conceptual framework necessary to develop causal arguments on broad social phenomena that are rooted in material remains (e.g., Lightfoot Reference Lightfoot1995; Preucel and Mrozowski Reference Preucel, Mrozowski, Preucel and Mrozowski2010:11–13). Due to the lack of deciphered Preclassic scripts, the literary horizon remains an issue for understanding warfare when Mesoamerican peoples first institutionalized rank and stratification. Fortunately Classic Maya writing is, to a large degree, deciphered, and this period has become a hotbed of research on warfare that can contribute insights for earlier and later periods (e.g., Earley 2023; Kim et al. 2023; Martin Reference Martin2020:196–236). Scholars, however, have underutilized Colonial-era records to examine Maya martial practice (Restall Reference Restall, Scherer and Verano2014). A better understanding of the practice of war in this later era can unravel Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period social dynamics and foster the development of models for the investigation of war-making. Thus, the Postclassic and Early Spanish Colonial period Maya cultural context, similar to the Classic period, can become a springboard to create conceptual frameworks and develop hypotheses pertaining to social conflict in other time periods.

By combining documentary and archaeological evidence with comparative insights on war-making, I examine how Maya peoples at Tzunun designed a martial landscape. Understanding human interactions with landscape allows me to address how elites utilized preparations for war to maintain power. I argue martial strategy and tactics framed local community life. Because Tzunun is fortified, the placement of buildings ties into Maya combat plans (i.e., tactics) and evince how elites protected their sources of power. By harnessing the sacred and martial power of elevated terrain, the local landscape provides evidence that like other Mesoamerican cultures, Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial-period (a.d. 900–1697) Maya martial strategy at Tzunun emphasized the protection of elites (e.g., Hassig Reference Hassig1988, Reference Hassig1992). This focus was not exclusive of commoners and other members of the community. Instead, differences in status led to varying levels of protection. One's literal place within the settlement served to perpetuate status distinctions. Critical to understanding these social dynamics is an examination of how well documented Mesoamerican conceptions of sacred geography, specifically those associated with elevated terrain, were incorporated with martial architecture to create a series of fortified zones (i.e., defense-in-depth).

To build my argument, I discuss how the concepts of strategy and tactics can be applied to the study of unequal social relations and landscape. Next, I elaborate on the concept of defense-in-depth to provide investigators with a means to think about how fortifications at Tzunun and other Mesoamerican sites were used and might have tied into local culture. I then combine the concepts of strategy, tactics, landscape, and defense-in-depth to examine how the process of fortification tied into the institutionalization of inequality at the site of Tzunun in Chiapas, Mexico.

MARTIAL STRATEGY, TACTICS, AND LANDSCAPE

Discussions of strategy and tactics in military history can be traced back to the work of Clausewitz (Reference Clausewitz1976 [1832]). His treatise, On War, outlined an approach to war as the continuation of policy via other means. The means being the application of maximum physical force against an enemy. War is a political instrument and in Clausewitz's cultural context, policy was in the hands of state actors (Lynn Reference Lynn2003). Strategy, or the overall political goal(s) of a particular military campaign, was determined by rulers and heads of state, hopefully in conjunction with members of military leadership. Tactics are how a war is actually conducted. In other words, tactics are how strategies are accomplished and being a military officer, Clausewitz focused on the organization of battle. Because all tactics should be directed toward accomplishing a strategic goal, every martial engagement can feed into networks of power.

Although his interest lay in everyday life and consumer practices, de Certeau's (Reference de Certeau and Rendall1984) analysis further highlights that strategy and tactics provide important distinctions that are tied to power and status. In practice, strategies are generated by the powerful and tactics are the potential realm for the creative manipulation of power relations. To build from his well-known example, strategy would be the top-down view of a city by an official who examines the overall urban plan to decide where streets, buildings, and neighborhoods should be located (de Certeau Reference de Certeau and Rendall1984). Note the similarity between an urban planner and general who organizes a battle. In contrast, tactics is the realm of the city-walker. Although urban planners can attempt to funnel movement and structure activity, the walker often finds creative new ways to engage with other forms of life and the city landscape. Creativity can include the relatively benign practice of parkour to the more potent use of civic space and city streets by the oppressed to protest police brutality. By understanding the structure of society and the affordances of a particular situation, people can perpetuate existing hierarchies and/or manipulate structures of power to their own benefit. Thus, strategy and tactics provide avenues to think about power, war-making, and social structure. I apply the concepts of strategy and tactics to examine interactions with a martial landscape.

Studies of landscape and earlier settlement pattern analysis have been concerned with how the organization of architecture and terrain can inform scholars about past social organization (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1981; Ashmore and Knapp Reference Ashmore and Knapp1999; David and Thomas Reference David and Thomas2008; Freidel and Sabloff Reference Freidel and Sabloff1984; Johnson Reference Johnson2007; Palka Reference Palka2014; Smith Reference Smith2003; Trigger Reference Trigger1967; Willey Reference Willey1953). Brady and Ashmore (Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999) demonstrate how the triumvirate of mountain-cave-water played an important role in shaping Maya landscapes and inequality. Temple-pyramids, which were conceptualized by many Maya peoples as mountains, were often placed in relation to caves and bodies of water (e.g., Vogt and Stuart Reference Vogt, Stuart, Brady and Prufer2005). At the Classic period site of Dos Pilas, the royal palace was centered over a cave that during the rainy season would emanate a rush of water from behind the structure. Because Maya rulers were associated with fertility and agriculture, the design of the royal palace asserted the ruler's power over water, and by extension rain-making and fertility (Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999:130). The inhabitants of Dos Pilas also utilized the tallest local hill to create the El Duende Pyramid, which was part of the largest architectural complex at the site. Brady and Ashmore (Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999:132) argue the “pattern of appropriating prominent sacred landmarks into public architecture reflects a larger strategy to sanctify and legitimate the city and, by extension, its leaders.” The use of mountains and height to instantiate and perpetuate power differences was an enduring aspect of Maya cultures.

Cross-culturally height is often associated with cosmological narratives and status (Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2008; Basso Reference Basso1996; Best Reference Best1993; Grapard Reference Grapard1982; McGuire and Villalpando Reference McGuire and Villalpando2015; Palka Reference Palka2002, Reference Palka2014). Throughout Mesoamerica, mountains and temple-pyramids formed important components of ritual landscapes. Ethnographically mountains can be homes for deities and powerful places to contact divine forces (Astor Aguilera Reference Astor Aguilera2010; Kapusta Reference Kapusta2016; Montejo Reference Montejo2001; Palka Reference Palka2014; Vogt and Stuart Reference Vogt, Stuart, Brady and Prufer2005). For example, during times of war, Jakaltek Maya would ascend a sacred mountain to seek divine protection from El Q'anil or “man of lightning” (Montejo Reference Montejo2001). During the Postclassic period and Spanish encounter, the Templo Mayor was a snake-mountain that marked the center of the cosmos and projected the strength of Aztec rulers through public ceremony that included large-scale sacrifice of captives (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2000). In addition to the ceremonial show of force, the imposing height of temple-pyramids likely projected an image of power. For example, the greater size and height of an individual in Classic Maya art signified high status (Palka Reference Palka2002). Consequently, triumphant rulers are depicted hovering over their lowly captives. In Mesoamerica, height and mountains were associated with power.

The above discussion highlights that Mesoamerican scholars have devoted much attention to the sacred and meaningful elements of landscape (Ashmore Reference Ashmore1991, Reference Ashmore2009; Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2008; Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999; Landau Reference Landau2015; Palka Reference Palka2014; Townsend Reference Townsend1992). Ashmore's (Reference Ashmore1991) work on cosmological designs at Copan has inspired investigators to examine ritual and cosmological landscapes at various scales of settlement. The authors in Landscape and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica built on the work of Ashmore and others to examine how performance and the construction meaning in monumental groups or a single civic-ceremonial structure can serve to promote social hierarchy (Koontz et al. Reference Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001). Tied to growth in the study of Maya warfare, researchers have also sought to examine how ritual landscapes figure into elite power and social conflict (Duncan Reference Duncan, Rice and Rice2009; Garrison and Houston Reference Garrison and Houston2019; Hernandez and Palka Reference Hernandez, Palka, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Morton and Peuramaki-Brown Reference Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019). For example, Reese-Taylor and Koontz (Reference Reese-Taylor, Koontz, Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001) demonstrate how the placement of war banners at the site of El Tajin served to promote polity cohesion and elite exclusivity. In the site's Central Plaza, the placement of 15 undecorated bases for banners at the foot of the Pyramid of the Niches was designed to foster the massing of multiple groups in a ritual reminiscent of banner raising at the base of Coatepec or the Templo Mayor at Tenochtitlan. The ritual involved the bringing together of banners to reaffirm the political community. The sanctuary atop Structure Four of El Tajin, however, contains a single base with elite iconography carved in the prestigious Classic Veracruz style (Figure 1). The high-status of the iconography chosen for the base and restricted access into the sanctuary reveal that elites created their own exclusive version of the banner ritual. Thus, the ritual landscapes of El Tajin bear the marks of how power and inequality were organized and perpetuated in the past. Separate banner raising rituals were used to affirm the polity and status distinctions. I examine the effects of war-making through the analysis of how power and status were supported via sacred and martial landscapes.

Figure 1. Banner stone from El Tajin carved in Classic Veracruz style. Drawing by Daniela Koontz.

As the focal points of public ritual, Mesoamerican temple-pyramids and their associated civic-ceremonial groups could support the power of the ruling elite. Conversely, an attack or destruction of a temple-pyramid or elements of a communities’ sacred landscape could seriously undermine the status quo (Hernandez and Palka Reference Hernandez, Palka, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019). A well-known example of these connections is the use of burning temple-pyramid imagery by Nahua artists to signify conquest and how during the Spanish encounter, Mexica temple-pyramids became places of refuge (Hassig Reference Hassig1988:105–106). In pre-Columbian times, the occurrence of Maya attacks to desecrate caves, temple-pyramids, and civic ceremonial groups reveal the importance of protecting sacred places (Brady and Colas Reference Brady, Colas, Prufer and Brady2005; Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997; Duncan and Schwarz Reference Duncan and Schwarz2015; Helmke and Brady Reference Helmke, Brady, Helmke, Sachse and Mesoamericana2014; Hernandez and Palka Reference Hernandez, Palka, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Pagliaro et al. Reference Pagliaro, Garber, Stanton, Brown and Stanton2003; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Serafin, Masson, Lope, Guzmán and Russell2017; Sheseña Reference Sheseña2014). Overall, the status of Maya and Mesoamerican rulers was tied with the ability to transform and protect sacred landscapes (Koontz et al. Reference Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001). I now turn to a discussion of specific tactics past Maya might have used to defend themselves and their sacred landscapes.

DEFENSE-IN-DEPTH AND COLONIAL-ERA MARTIAL TACTICS

Defense-in-depth is a tactic of creating fortified zones to face an oncoming force (Hill and Wileman Reference Hill and Wileman2002:102; Lupfer Reference Lupfer1981). Instead of creating one linear zone to confront an enemy, the point is to wear down opponents by making them confront multiple areas that have been prepared for war. The trench systems of World War 1 are examples of defense-in-depth. The European Western Front was composed of a series of trenches running roughly parallel to one another that were traversed via covered or exposed paths (Figure 2). If the first line of trench was breached the succeeding lines could provide combat support and attempt to prevent a total rupture of the fortified front. Overall, the goal of defense-in-depth is to slow and stall, if not outright prevent, an attack through the creation of layers of defense. The general stalemate and millions of casualties that resulted from trench warfare in World War 1 provide testament to the deadly potential of this tactic. Although lacking the martial capabilities of industrialized nations, I demonstrate how defense-in-depth applies to Maya peoples.

Figure 2. Image of World War I trenches at St. Eloi, Belgium. Modified from an image published under Creative Commons License by the National Library of Scotland (https://digital.nls.uk/74549740).

Similar to earlier eras, Late Postclassic and Early Spanish Colonial Maya warfare was dominated by the use of infantry (e.g., Hassig Reference Hassig1992; Repetto Tió Reference Repetto Tió1985; Webster Reference Webster, Feinman and Marcus1998, Reference Webster2000). Prior to the arrival of the Spanish and their horses, there is no evidence of mounted warriors (i.e., cavalry) in the Americas. Instead, combat generally involved warriors on foot. Maya warriors can be divided into shock and projectile forces. Shock forces primarily used their body and handheld implements, such as a thrusting spear or club, to make contact with an opponent. Projectile wielding warriors typically operate at distance by firing an object through the air that will hopefully make contact with a target. Although available during the Classic period, it was during the Postclassic that the bow-and-arrow became widely used in the Maya area (Aoyama Reference Aoyama2005; Aoyama and Graham Reference Aoyama and Graham2015; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Rice, Pugh, Polo, Rice and Rice2009). In Chiapas, as in other parts of Mesoamerica, Spanish and Indigenous historians noted the use of canoes for war (De Vos Reference De Vos1980, Reference De Vos1990; Feldman Reference Feldman2000; Jones Reference Jones1998; Nance et al. Reference Nance, Whittington and Jones-Borg2003). The use of canoes in Maya combat requires further detailed study of available sources (de Villagutierre Reference de Villagutierre and Wood1983[1701]; De Vos Reference De Vos1980, Reference De Vos1990; del Castillo Reference del Castillo2008; Feldman Reference Feldman2000; Jones Reference Jones1989; Nance et al. Reference Nance, Whittington and Jones-Borg2003; Thompson Reference Thompson1970; Webster Reference Webster2000; among others) to develop an overall picture of this type of warfare along with hypotheses for archaeological investigation in regions not documented by Colonial-era chroniclers. Consequently, I focus on terrestrial martial practice but acknowledge the past use of watercraft in war.

Despite the presence of fortifications throughout Mesoamerica during the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period, there is a lack of documented siege weaponry (e.g., Armillas Reference Armillas1951; Hassig Reference Hassig1988, Reference Hassig1992; Palerm Reference Palerm1956; Repetto Tió Reference Repetto Tió1985; Webster Reference Webster2000). Siege weapons among the Aztecs were limited to ladders and fire (Hassig Reference Hassig1988:108–109). Otherwise, they would rely on a ruse or cunning to enter a fortified settlement. It is interesting to note, however, the presence of siege towers in the Terminal Classic (a.d. 800–1000) murals of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars at Chichen Itza (Figure 3). Thus, iconographic evidence highlight the dynamics of Maya martial practice and that some technologies of war have been lost over time. It is unclear how frequently siege towers were employed in martial engagements, and there is no extant evidence the pre-Columbian Maya used battering rams, mining technologies, or catapults to assault fortifications.

Figure 3. Siege towers from the Terminal Classic (a.d. 800–1000) murals of the Upper Temple of the Jaguars at Chichen Itza. Image courtesy of Bridgeman Images.

The Process of Fortification

In Maya martial practice it was common to fortify terrestrial access points such as paths. Barricades could stop or slow advancing warriors and send a message of martial intent. Fray Diego de Landa reports that along paths, the Maya would station archers and place barricades that could be made of stones, trees, and stakes (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:123). During their Entrada in Guatemala, Pedro de Alvarado and his armed forces repeatedly encountered fortifications along paths. In a letter to Hernán Cortés, Alvarado reports that on his approach to the town of Zapotitlan, “I found they had left the highroads and crossroads open, but had closed the roads leading into the main streets, and I judged that their reason for doing this was to make war on us” (de Fuentes Reference de Fuentes1963:184). On the march to Xelaju (Quetzaltenango) Alvarado describes how, “we began to climb a pass six leagues long…This pass was so steep we could barely take the horses up…Further on I found a strong wooden barricade in a narrow gap, but there was no one in it” (de Fuentes Reference de Fuentes1963:185). The Lienzo de Quauhquechollan provides the perspective of Nahua speakers who accompanied Alvarado during his Entrada (Asselbergs Reference Asselbergs2004). There are numerous scenes in the lienzo with pits of sharpened stakes and wooden fortifications along paths like the barricades described by Landa (Figure 4). Blocking a road would not necessarily stop Mesoamerican warriors but could hinder movement. Drawing from Hassig, Asselbergs (Reference Asselbergs2004:132) argues the presence of fortifications along paths “were a political statement: they signaled the intention to sever relations, resist hostile passage or entry, or initiate a war. When a subjected town or an independent city blocked its roads, this was regarded as an act of rebellion (Hassig Reference Hassig1988:8).” Documentary and archaeological evidence also reveal a highland Maya practice of fortifying communities and their access points via the use of elevated and rugged terrain.

Figure 4. (a) Pit with sharpened stakes and (b) road with wooden barricade in the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan. Images redrawn from Restall (Reference Restall, Scherer and Verano2014).

Mountainous, rugged terrain has been utilized cross-culturally to create martial landscapes (Allen Reference Allen, Arkush and Allen2006; Arkush Reference Arkush2011; Blake Reference Blake2010; Brice Reference Brice1990; Dyer Reference Dyer1992; Haas and Creamer Reference Haas and Creamer1993; Fox Reference Fox1987; Lau Reference Lau2010; Martindale and Supernant Reference Martindale and Supernant2009; McGuire and Villalpando Reference McGuire and Villalpando2015; Minge Reference Minge1991; Müth et al. Reference Müth, Schneider, Schnelle and De Staebler2016). Based on his experience in the K'iche Maya community of Utatlan (Q'umarkaj), Alvarado (de Fuentes Reference de Fuentes1963:186) states “…the city is very strongly fortified, and has two entrances…since the city is very compact and the streets narrow, we could not have resisted an attack without being cut off, nor have escaped…without throwing ourselves down the [nearby] embankment.” In other words, thoroughfares and local terrain constrained movement within the community. Archaeological investigations at Utatlan have revealed clusters of dense settlement surrounded by barrancos or ravines (Babcock Reference Babcock2012; Carmack Reference Carmack1981). A combination of archaeological and documentary evidence support that Utatlan's inhabitants utilized the local highland terrain to restrict pedestrian movement in and out of the site.

In their review of fortified sites in the highland Huista-Acatec region of Guatemala, Borgstede and Mathieu (Reference Borgstede and Mathieu2007) argue that mountaintop sites and intra-site planning (i.e., inner fortifications) became more common during the Postclassic period. To support their case, they gather ethnohistoric data on how the Kaqchikel Maya funneled Spanish-led warriors into an alley at Iximche (Borg Reference Borg, Nance, Whittington and Borg2003). This tactic is similar to what Restall (Reference Restall, Scherer and Verano2014:103–109) calls “urban ambush” or the Maya use of dense settlement on rough, broken terrain to trap and launch a surprise attack on Spanish-led forces. In addition to Borgstede and Mathieu's comparative research, the above description of Utatlan by Alvarado highlights that narrow walkways were important considerations in martial practice (de Fuentes Reference de Fuentes1963:185). Highland Maya utilized the pedestrian constraints posed by local geology to create layers of defense within their communities. Moreover, the Maya would incorporate bodies of water into the design of martial landscapes.

It was common for Maya peoples during the Postclassic and Early Spanish Colonial period to fortify terrain where bodies of water could be used to restrict pedestrian access (e.g., Bassie-Sweet et al. Reference Bassie-Sweet, Laughlin, Hopkins and Casimir2015; Chase and Rice Reference Chase and Rice1985; Kennett et al. Reference Kennett, Masson, Serafin, Culleton, Lope, VanDerwarker and Wilson2016; Schwarz Reference Schwarz2013). During his martial campaign against the Maya of Lake Atitlan, Alvarado encountered “a city on a large lake…strengthened by the lake and the canoes they had…” (Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007:37). When approaching the “city on the large lake,” which Alvarado also refers to as a “peñol,” he reports encountering Maya who “got onto a very narrow causeway which entered the rock [peñol]…we entered the rock so that they had not time to break down the bridges…” (Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007:37). Like Alvarado, Cortés also reports how paths, rugged terrain, and lacustrine settings were important components in the Mesoamerican practice of war.

During his a.d. 1525 punitive expedition to Honduras, Cortés describes many regions and Maya groups, such as the Acalan, Kehach, and Peten-Itza (Pagden Reference Pagden1986). Although the ethnicity(ies) of the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period Maya of Tzunun is unknown, members of the community interacted with people from the Acalan, Kehach, and Peten-Itza regions (De Vos Reference De Vos1980, Reference De Vos1990; Palka Reference Palka2005; Pugh Reference Pugh, Rice and Rice2009). In his fifth letter to the King of Spain, Cortés describes a fortified settlement in the Kehach region that bears strong similarity to Tzunun:

“It was so well fortified, however, that we could find no way in, and when at last we found a way, we discovered it had been abandoned…This town stands upon a high rock: on one side it is skirted by a great lake and on the other by a deep stream which runs into the lake. There is only one level entrance, the whole town being surrounded by a deep moat behind which is a wooden palisade as high as a man's breast. Behind this palisade lies a wall of very heavy boards, some twelve feet tall, with embrasures through which to shoot their arrows; the lookout posts rise another eight feet above the wall, which likewise has large towers with many stones to hurl down on the enemy. There are also embrasures in the upper parts of all the houses, facing outwards, and likewise embrasures and traverses facing the streets; indeed, it was so well planned with regard to the manner of weapons they use, they could not be better defended” (Pagden Reference Pagden1986:371).

Cortés provides a clear description of how the Kehach created a community with layers of fortification to counter an attack. Initially, bodies of water restrict access to the settlement. Next, utilizing the generally rugged local terrain, the Kehach created multiple layers of barricades across the most level ground into the community. Attacking across the spit of land that connected the site to the mainland would require the assaulting force to navigate across a moat, followed by two layers of palisades. If attackers could breach the barricades, then the site's inhabitants could utilize the local rugged terrain to continue fighting and fire projectiles from their rooftops. Thus, the occupants of the site organized their community and local landscape according to the tactic of defense-in-depth by creating layers of defense to slow and stall an attack. The past inhabitants of Tzunun employed this same basic martial plan.

TZUNUN, CHIAPAS, MEXICO

Situated within the Naha-Metzabok UNESCO Biosphere Reserve and the smaller region of Mensabak, Tzunun is a small to medium sized (~14 ha during the rainy season) site with rugged, mountainous terrain. The settlement is located on the southeastern shores of Lake Tzibana (Figures 5 and 6). Due to its lacustrine setting, the site becomes an island during the rainy season and peninsula in the dry season. The contemporary peoples, primarily Lacandon and Tzeltal Maya, of Puerto Bello Metzabok employ the shifting shorelines on the southwestern end of the site to dock boats. In collaboration with the local community, I conducted a full coverage survey and mapped of 5.65 ha of Tzunun (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The Mensabak Region of Chiapas, Mexico. Maps by the author and Santiago Juarez.

Figure 6. Map of Tzunun. Map by the author.

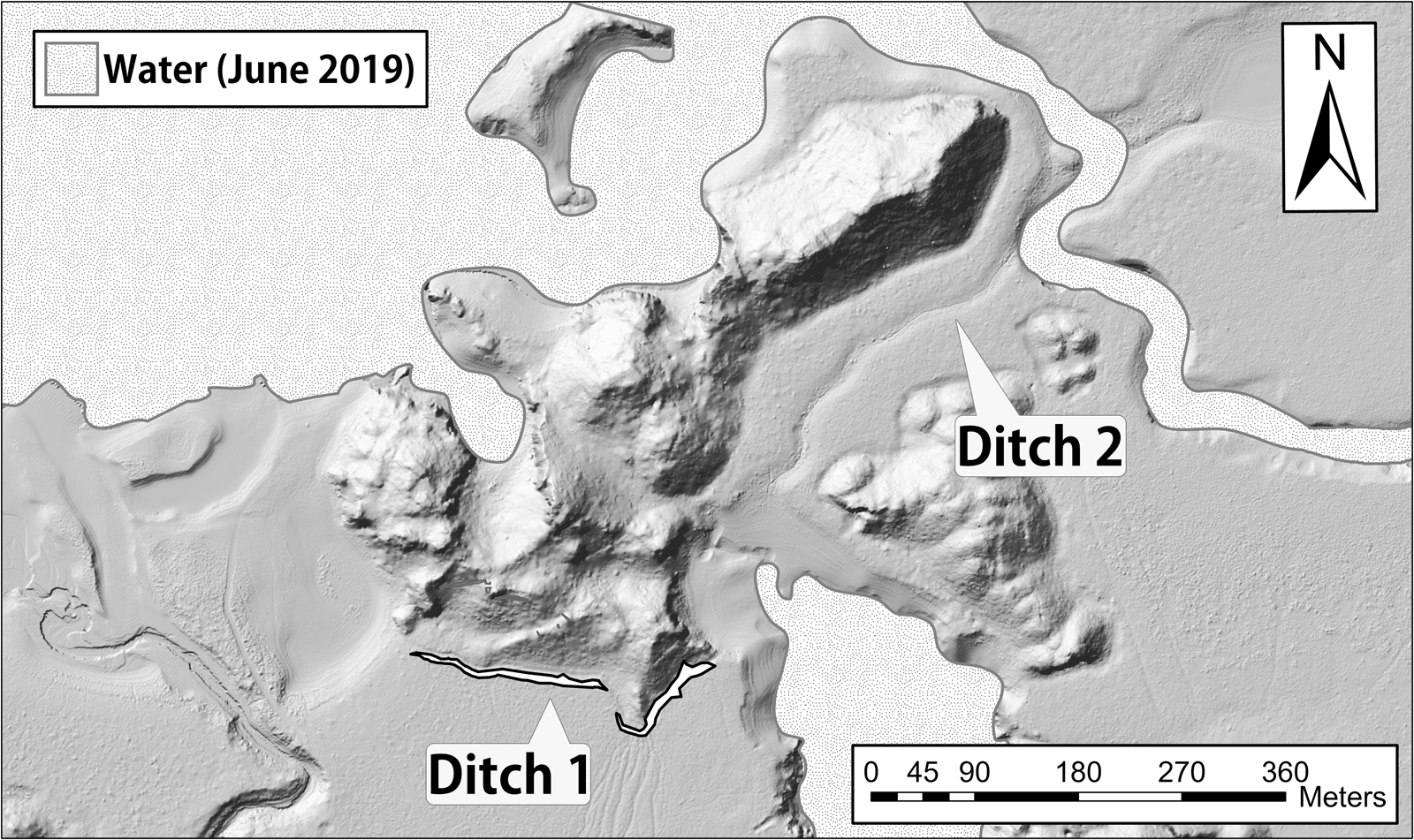

During the initial mapping of the site, local Maya and I measured Tzunun's topography at 5 m intervals. We recently supplemented this work with aerial lidar data (Figure 7). The topographic data revealed an undulating terrain that rises from the relatively level flood plain that marks the end of Tzunun's architectural remains (Figure 8). In order to access the site and understand the local landscape, one must go up, then down, and then up some more. Furthermore, Tzunun's structures cluster on peaks in the topography. The rugged topography with structures clustering on elevated terrain suggested internal fortifications (e.g., Arkush Reference Arkush2011; Haas and Creamer Reference Haas and Creamer1993; Martindale and Supernant Reference Martindale and Supernant2009).

Figure 7. Combined Digital Elevation Model and Digital Surface Model of Tzunun. Map by the author.

Figure 8. Profile image of Tzunun's Terrain. Image by the author.

As part of my 2016 dissertation fieldwork, local Maya and I excavated the site's fortifications, ritual, administrative, and residential areas. Through 15 test pits and 361 shovel test pits, we sampled midden associated with a temple group and 11 potential residential mounds. We also sampled potential fortifications on the southern end of the site via eight test pits and two trench excavations (Figure 9). Although our sampling universe only covered about 40 percent of the site's surface area, the relationships among height, warfare, and status are clearly visible.

Figure 9. Excavations along Tzunun's fortifications. Photograph and map by the author.

Tzunun was occupied during the Late Preclassic (200 b.c.–a.d. 200) and Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period (a.d. 900–1600; Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017). Limited evidence of Preclassic occupation clusters around the site's highest peak. Our investigations, however, have yet to reveal evidence of martial architecture during this early phase of occupation. The majority of the site's surface remains date to the Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period. My analysis is focused on this later portion of Tzunun's history.

During the Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period, dwellings and civic-ceremonial architecture within Tzunun are clustered on peaks in the topography. I attempted during several field seasons with local Maya to map a rock outcrop that is about five meters southeast of Tzunun's highest peak (Figure 10). The outcrop has sheer sides that make the geologic feature look like a large pillar of stone. The top of the pillar has an area of roughly four m2 that from a distance appeared to contain a level surface. In the summer of 2016, Josué de Jesus Gómez Vázquez found a climbable section of rock face and at the top of the outcrop observed two courses of stone forming a structure with roughly rectilinear sides. Bees thwarted all our attempts to map the construction. Despite the setback, the sheer sides mean that the only manner to build on the rock outcrop was to climb with tools and construction materials to the top of the stone pillar. Otherwise, a small bridge would have to be created from the site's highest peak to the top of the outcrop (Figure 10). For Tzunun's occupants, it was important to build on elevated terrain.

Figure 10. View when standing behind (i.e., attempting to look at the rear ZN-K-1) Tzunun's highest peak and nearby rock outcrop. Images not to scale. Drawing by Josué de Jesús Gómez Vázquez and the author; photograph by the author.

On the site's highest peak, Tzunun's inhabitants filled in a rock outcrop to create a level area for construction. The fill contains Late Postclassic to Early Spanish Colonial period ceramics (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017). On the leveled terrain, the Maya created multiple small basal platforms and an approximately three-meter-tall structure (ZN-K-1), which is a large masonry basal platform with a central stairway (Figure 11). The staircase is oriented toward a temple-pyramid. On the top of the structure there is a low rectangular feature made of masonry. ZN-K-1 is one of the largest buildings at Tzunun, and the low rectangular feature at the top of the structure may be an altar or the remnants of a base for a pillar similar to those found at other Postclassic Maya sites (e.g., Rivero Torres Reference Rivero Torres and Botello1992). The size and masonry construction of ZN-K-1 suggested it was associated with people of high status (Palka Reference Palka1997; Pugh Reference Pugh2004; Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:86–87).

Figure 11. Architecture on Tzunun's highest peak and the aligned temple group. Map by the author.

Shovel test pit (30 × 30 cm) and test pit (2 × 2 and 1 × 1 m) excavations revealed a general a lack of artifacts on Tzunun's highest peak (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017:209–216). Further sampling along the base of the precipice behind the summit also revealed a lack of artifacts. Due to the general paucity of artifacts in and around the site's highest peak, I argue the structures on the summit are not the remnants of a household. Instead, ZN-K-1 and the other constructions on the peak had primarily administrative and ritual functions.

Investigations just below the entrance to the summit revealed that Tzunun's inhabitants created stairs leading to a small basal platform for a structure that might have been used to control access to the peak (Figure 11). Excavation of the area inside and outside of the small basal platform below the summit entrance revealed a general lack of artifacts. The few recovered diagnostic ceramics date to the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017:216–219). The paucity of recovered artifacts, similar to ZN-K-1, suggest the small platform just below the entrance to the summit and associated stairs had an administrative function, namely monitoring and/or restricting access to the architectural group on the peak.

Researchers have established that the divine associations and ritual power of Mesoamerican ruling elites were vital for the maintenance of their status (Carrasco Reference Carrasco2000; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Schele and Parker1993; Hernandez and Palka Reference Hernandez, Palka, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1996; Martin Reference Martin2020; Schele and Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986). Similarly, war and other political matters were entangled with ceremony and cosmology. Evidence of this connection is provided by the protection and destruction of temple-pyramids, civic-ceremonial groups, and other Maya sacred places (Brady and Colas Reference Brady, Colas, Prufer and Brady2005; Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997; Duncan and Schwarz Reference Duncan and Schwarz2015; Helmke and Brady Reference Helmke, Brady, Helmke, Sachse and Mesoamericana2014; Hernandez and Palka Reference Hernandez, Palka, Morton and Peuramaki-Brown2019; Pagliaro et al. Reference Pagliaro, Garber, Stanton, Brown and Stanton2003; Paris et al. Reference Paris, Serafin, Masson, Lope, Guzmán and Russell2017; Shesheña Reference Sheseña2014). At Tzunun, the staircase of ZN-K-1 is oriented toward a temple-pyramid (Figure 11). Surface reconnaissance of the plaza in front of the temple-pyramid revealed a possible altar in line with the orientation of ZN-K-1 toward the temple-pyramid but excavations are necessary to confirm the altar hypothesis. Because the status of Mesoamerican rulers was tied to ritual power and divine forces, the orientation of ZN-K-1 toward a temple-pyramid provides evidence that local elites, perhaps rulers, sought to maintain their status through a combination of cosmology, ceremony, and political power.

Tzunun's inhabitants worked with the local mountainous terrain to create civic-ceremonial architecture. Located on the highest point of the peninsula's mountainous terrain, ZN-K-1 is one of Tzunun's largest masonry structures and faces a temple group. Consequently, the architecture on the site's highest summit incorporates elite displays of status through large masonry architecture, elevation, sacred/cosmological conceptions of mountains, and a physical orientation toward a temple-pyramid (i.e., also a mountain) to create a ritual landscape. Lack of artifacts on or around the peak reveal that ZN-K-1 and the other constructions on the summit are not the remnants of a household. Instead, I argue that through their connection to elite ritual power, the structures on the peak would have had politico-administrative functions. With access to the peak perhaps hindered by people stationed in a structure located below the entrance to the summit, Tzunun's highest peak was a place of power where local elites maintained their status within the community. Similar to other Mesoamerican communities, such as Dos Pilas and El Tajin, the inhabitants of Tzunun channeled the power of mountains and height to instantiate status distinctions (e.g., Bassie-Sweet Reference Bassie-Sweet2008; Brady and Ashmore Reference Brady, Ashmore, Ashmore and Knapp1999; Palka Reference Palka2002, Reference Palka2014; Reese-Taylor and Koontz Reference Reese-Taylor, Koontz, Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001; Schele and Kappelman Reference Schele, Kappelman, Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001).

High-status occupation of Tzunun's elevated terrain extends to the second highest hilltop within the sampling area (Figure 12). I assessed status of occupations through a comparison of architecture, and the quantity, quality, and variety of recovered artifacts. Hernandez (Reference Hernandez2017:170–273) provides a detailed account of this analysis, of which I provide a summary of results. On the second highest hilltop, located west of ZN-K-1, local Maya and I mapped large masonry basal platforms that together form a patio group (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017:220–227). Excavations revealed large quantities and varieties of artifacts, including some made of metal (one copper-based and another unidentified), greenstone, and marine shell. Further sampling of dwellings around this apical group revealed occupations of varying status. In sum, people of high status occupied Tzunun's second highest hilltop and people of varying statuses lived at lower elevations. Findings from two apical groups at Tzunun reveal evidence of high-status occupation on summits.

Figure 12. Apical group west of ZN-K-1. Map by the author.

Tzunun's Series of Fortifications

Tzunun's fortified landscape can generally be categorized into inner and outer fortifications. The outer fortifications include the hydrology, topography, and martial architecture that form the outline of settlement. The inner fortifications are composed of the site's rugged terrain and the placement of buildings.

Tzunun's outer fortifications begin with a combination of local topography and hydrology. The site is an island or peninsula depending on the season. During the dry season, when Tzunun is a peninsula, most of the site is surrounded by water and pedestrian access is restricted to the northeastern and southern ends of the site (Figure 7). A ditch traverses both land accesses. On the southern end of the site, our total station mapping revealed the ditch is 328 m long and has a general depth of 1–1.5 meters (Figure 6). The western portion of the ditch is backed and fronted by earthen mounds. The tallest mound backs the ditch and reaches a height of one m (Figure 13). The smaller mound fronts the ditch and is barely discernible on the surface. The mounds are located at the entrance of the path that contemporary Maya forest rangers use to patrol Tzunun. Due to its location across the southern land bridge into the site, the ditch and mounds could be part of Tzunun's Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period fortifications. A lack artifacts recovered from the earthen features, however, has made chronometric interpretations difficult and my analysis is ongoing. Consequently, my discussion of Tzunun's martial landscape is focused on the stone martial architecture.

Figure 13. Profile of Tzunun's ditch and mounds. Drawing by Heriberto Valenzuela Gómez, Kristin Landau, and the author.

Past Maya blocked the contemporary path into Tzunun with two masonry walls (Figure 9). This walkway is a narrow corridor between two ridges. Aside from the walls, the corridor provides a relatively gentle slope into the site. The first wall (Wall 1) is a masonry retaining wall that is approximately one meter tall and 5.7 m long at its top. The second wall (Wall 2) is a masonry free-standing wall that is 1.2–1.8 m tall, 15–17 m long, and 8.5–10 m wide (Figure 9). Excavation of both walls revealed ceramics mainly from the Late Postclassic to Early Spanish Colonial period (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017:376–377). Based on comparative documentary and archaeological evidence, the walls in the corridor barricaded the gentlest slope into the community. Like the fortifications encountered by Alvarado at Lake Atitlan and Xelaju, the inhabitants of Tzunun blocked the narrow access into the site. Perhaps the narrow, fortified corridor contained bridges similar to those constructed by the inhabitants of Lake Atitlan (Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007:37).

At Tzunun, Maya peoples also created a series of free-standing walls on the apex of the ridgeline to the west of the barricaded path (Figure 14). The walls contain four gaps and are occasionally interrupted by small hills with evidence of low stone architecture on their peak. It is possible the hills are the remnants of bastions or the “towers” described by Cortés (Pagden Reference Pagden1986:371) and archaeologically documented as part of Classic period fortifications by Scherer and Golden (Reference Scherer and Golden2009). Future excavations are necessary to confirm my hypothesis. Excavation of one gap along the barricades revealed that below the surface much of the wall was still intact (Figure 14). Therefore, the walls were partially dismantled in the past, which resulted in the breaks documented on the surface. It remains unclear why the constructions were dismantled. Perhaps the gaps resulted from martial activity, lack of maintenance in the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period, activities by Lacandon Maya who re-occupied Tzunun to create farm plots, or some combination of these factors. A 14C sample recovered from the context below the dismantled wall provided a date of cal. a.d. 1034–1165 (2σ, IntCal13 atmospheric) or the Early Postclassic (Figure 14). The ceramics recovered from the context above the radiocarbon sample, which is also the context that contains the foundations of the wall, primarily date to the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period (Hernandez Reference Hernandez2017:204–205, 358, 378–379). My discussion of trends in Maya fortification construction supports that similar to the fortifications described by Cortés, the series of walls on the ridge are the remains of martial architecture used to create a layer of defense beyond the walls blocking the narrow pass into the site.

Figure 14. Map of fortifications along the southern ridgeline of Tzunun. Circles denote gaps along the walls. Images and photograph by the author.

DISCUSSION

The documentary evidence presented above demonstrate that Maya peoples intentionally built fortifications to block areas of pedestrian access. Cortés's description of a Kehach site revealed that when fortifying a path leading toward a peninsula, the Maya would build a series of barricades that included walls and ditches. Tzunun's ditches are located across the spits of land connecting the site to the mainland. Survey and excavation at the southern end of the site revealed the ditch was associated with mounds. The mound features are located at the entrance of a narrow corridor where local topography provides a gradual slope into the site. Although speculative due to lack of chronometric data, perhaps the mounds were part of a temporary and/or incomplete addition to Tzunun's series of fortifications. Nevertheless, the series of walls at the southern end of the site provide evidence that Tzunun was fortified during the Late Postclassic/Early Spanish Colonial period.

Along the southern edge of settlement, the site's inhabitants created a series of masonry fortifications to repel an infantry attack. Two masonry walls block the gentlest slope into the site. The barricades along the path are bolstered by fortifications that run along a nearby ridge. Tzunun's inhabitants created a series of walls on the ridge that are interrupted by hills with evidence of low masonry architecture on their peaks. Due to their placement along the walls, the hills may be bastions or towers similar to those described by Cortés, and Scherer and Golden (Reference Scherer and Golden2009). The interior of Tzunun bears further similarity to the Kehach site visited by Cortés.

Tzunun's inner fortifications incorporate the local, rugged topography to create layers of defense. If the outer defenses were breached, then the local rugged landscape would present obstacles for attacking warriors. Furthermore, the placement of structures on and around high points in the local terrain added to the site's overall martial landscape because height provided defenders with greater potential visibility (i.e., lines-of-sight) and the mechanical advantage of gravity. The bow-and-arrow is one of the most frequently reported weapons in ethnohistoric documents, and was in common use during the Late Postclassic and Early Spanish Colonial periods (e.g., De Vos Reference De Vos1980; Meissner and Rice Reference Meissner and Rice2015; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Rice, Pugh, Polo, Rice and Rice2009). It is likely other types of projectile weapons were also in use at Tzunun and we found one potential slingstone during excavations (Figure 15). Excavations also revealed some evidence of projectile points but further lithic analysis is necessary to determine if they were used or designed for use in martial combat. Whether Maya peoples used a bow, sling, atlatl, or any other means to launch objects through the air, fighting from higher ground allowed Tzunun's defending infantry to fire projectiles and charge with greater force, while potentially expending less overall energy than people approaching from lower terrain. In contrast, attacking infantry would have to work against gravity to attack opponents on high ground. Moreover, like the conquistadors at Utatlan or Iximche, warriors assaulting Tzunun could be trapped within the dense architecture and broken terrain of the site (Figure 6). Tzunun's mountainous terrain, including the pillar of stone that was a struggle to map, could have provided high points for refuge, defense, and perhaps places to launch counterattacks. In short, Tzunun was a fortress.

Figure 15. Projectiles recovered from Tzunun with potential martial function. (a) Potential slingstone. (b–d) Sample of projectile points. Photographs by the author.

Through the combination of inner and outer defenses, Tzunun's inhabitants worked with the local landscape to create defense-in-depth. Pedestrian access is limited to small strips of land that are only available during the dry season. Otherwise, the site would have to be attacked via amphibious assault. Similar to the ethnohistoric examples above, Tzunun's inhabitants likely had canoes ready in case attackers approached via watercraft, but such an argument remains speculative. Boat docks are difficult to locate, and ancient wooden watercraft rarely preserve in the Maya area. Nonetheless, various Colonial-era chroniclers describe encounters with Maya warriors on canoes in Chiapas and nearby Guatemala (De Vos Reference De Vos1980, Reference De Vos1990; Feldman Reference Feldman2000; Jones Reference Jones1998; Restall and Asselbergs Reference Restall and Laurence Asselbergs2007; Scholes and Roys Reference Scholes and Roys1948; Thompson Reference Thompson1970). Adding to Tzunun's martial landscape, the southern land bridge into the site was fortified by multiple masonry walls. The stone martial architecture might have been bolstered by ditches and earthen mounds. The narrow pass between the ridges along Tzunun's southern boundary was blocked by two walls. The site's inhabitants also created a series of fortifications on the ridge west of the fortified path. If the outer defenses were breached, attackers would then have to navigate the inner, broken terrain of the community. Buildings were constructed on and around peaks in the topography. Therefore, locals could take advantage of higher ground when defending their homes and other parts of their community. Perhaps Tzunun's inhabitants were ready to turn their dwellings into temporary fortifications. Cortés reports that a Kehach site, which resembles Tzunun in terms of topography and fortifications, had dwellings with the superstructures modified to create embrasures that allowed defenders to strike people walking on thoroughfares. Similar to the Kehach site described by Cortés, architecture at Tzunun was incorporated with rugged, elevated terrain to wear down opponents. The local landscape was designed for the tactic of defense-in-depth or to wage war in a manner that made attackers confront multiple zones that had been prepared for war.

Understanding the tactical design of Tzunun reveals past Maya strategy. Within Tzunun's layers of fortification, higher terrain would have been better defended than lower terrain. Survey and excavation revealed that on the highest and most well-defended location in the community, the site's inhabitants created ZN-K-1, which was a ritual/administrative structure. Because the building faced a temple-pyramid, the presence of a potential altar on ZN-K-1, and likely hindered access to the summit, I argue that, similar to El Tajin, Tzunun's highest peak served as a more private space for elite political administration and ritual. Perched atop ZN-K-1, Tzunun's elites had greater security and could potentially look down on the public performances that occurred in the temple group below. Although more complicated due to people of varying status living at lower elevations, we nonetheless see high-status occupation on the summit of a second apical group located west of ZN-K-1. Elite occupation of the most well-defended terrain in the community provides evidence of past strategy.

A general emphasis in Mesoamerican warfare, like contemporary wars among nation-states, was the protection of elites and their status. Via the implementation of defense-in-depth and elite occupation of higher terrain, we see how the rest of the community is less protected and becomes a potential buffer to protect elite status and power. The varying levels of protection would have affected the course of an attack on the site and was designed to maintain status differences.

The tactic of defense-in-depth was employed to protect the inhabitants of Tzunun, with strategic primacy given to protecting elite occupation and, above all, the ritual/administrative structures on the site's highest peak. Thus, sacred geography and civic-ceremonial architecture were incorporated into a martial landscape. This strategy makes sense within current Mesoamerican scholarship because I highlight that status was tied to the protection of sacred landmarks and ritual landscapes. By understanding the tactical scheme of Tzunun's landscape, one can see how preparations for war actively contributed to the instantiation and maintenance of status distinctions by affording elite occupations greater protection. Past Maya institutionalized inequality via the martial design of Tzunun's landscape.

Returning to the wider interpretative question of this paper, archaeologists can tangibly connect social processes and material remains by understanding how past people practiced war. In other words, my analysis positions human activity as a mediator that connects the archaeological record with the processes of war and the institutionalization of inequality. To flesh out the human activity associated with material remains, I paired documentary records with comparative insights on war to argue Tzunun's martial landscape was designed to create defense-in-depth. Understanding the tactic of creating multiple zones of inner and outer fortifications (i.e., defense-in-depth) revealed that nested within this martial plan were the means to instantiate and perpetuate status distinctions by affording greater protection to elite occupations. This durable landscape design would have had long-term effects and thereby provided a means to institutionalize inequality. By understanding tactics, strategy, and the particulars of martial practice, the material indicators of war can be more powerfully analyzed to develop causal arguments for social processes. With the large corpus of available documentary, iconographic, and hieroglyphic records from the Colonial and pre-Columbian eras, Maya archaeologists are less burdened by the literary horizon. A wealth of potential data is available to flesh out pre-Columbian war-making; the only question is whether we are willing to dig into the details of practice.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, I examined the tactics employed by the inhabitants of Tzunun, Chiapas, Mexico, to fortify their community and demonstrated how this martial design tied into the institutionalization of inequality. Through a combination of documentary, archaeological, and comparative analysis, I determined the site was a heavily fortified through a combination of inner and outer fortifications to create defense-in-depth. If the outer fortifications were breached, defenders could fall back to the elevated and rugged terrain within the community to wear down attackers. Within the site's martial landscape, elevation and elements of sacred geography were critical. High, mountainous terrain afforded potential refuge and higher levels of protection.

Given its tactical advantage, the site's highest peak is a place of ritual and political administration. The largest structure on the summit is physically oriented toward a temple group that together denote a ritual landscape. Because the maintenance of ritual landscapes and sacred landmarks was central to elite Maya authority, the local martial landscape was designed to afford the greatest protection to places and symbols of high status. Examination of a nearby hilltop also revealed high-status occupation on the peak. Thus, a trend is beginning to emerge of elite occupation on hilltops.

War could have affected and involved all segments of the population, but the protection of elite occupations and sources of power were points of emphasis in the martial decision-making process at Tzunun. Because people of high status occupied the most well-defended portions of the site, the community's defense-in-depth was designed to provide greater protection for elite power and high status. Similar to conquest era accounts, Tzunun's martial landscape provides further evidence for the strategic importance of elites in Mesoamerican warfare. Ritual, cosmology, and Tzunun's martial landscape supported differences in status.

By unpacking the particulars of practice with a martial landscape, I linked the material indicators of war and inequality to demonstrate that the process of fortification actively contributed to the institutionalization of inequality. This research provides insights for future analysis of other Mesoamerican sites such as Zacpetén and Punta de Chimino in Guatemala (e.g., Bachand Reference Bachand2006; Demarest et al. Reference Demarest, O'Mansky, Wolley, Van Tuerenhout, Inomata, Palka and Escobedo1997; Rice et al. Reference Rice, Rice, Pugh, Polo, Rice and Rice2009). Both sites have a similar settlement pattern to Tzunun, with multiple fortifications along the spit of land that connect the sites to the mainland. Understanding the importance of height, hydrology, and terrain for creating defense-in-depth at Tzunun, it might prove fruitful to examine how this tactic was employed at Zacpetén, Punta de Chimino, and other Mesoamerican sites with similar martial designs. Could it be that the tactical and strategic design of the local landscape maintained aspects of local culture? In the end, my investigation of martial practice reveals that preparations for war were integral for the perpetuation of inequality at Tzunun.

RESUMEN

Aunque los estudios de la guerra ahora son comunes en la arqueología de los mayas, queda mucho por conocer sobre la estrategia, tácticas y varios otros factores prácticos en el proceso de hacer la guerra. Estudios de sociedades en Eurasia y África destacan que la práctica marcial humana puede tener profundos impactos en la economía política, el paisaje, y la cultura. Por lo tanto, un énfasis en el aspecto concreto y práctico de la guerra es necesario para reconocer la agencia y comprender cómo se relaciona el conflicto con la experiencia humana. A través de un examen de datos etnohistóricos, iconográficos y arqueológicos, profundizo el conocimiento de las prácticas de construcción de fortificaciones mayas y cómo la creación de un paisaje marcial se relaciona con el poder durante el posclásico tardío y período colonial temprano (1200–1600 d.C.). Durante estos tiempos, en el sitio de Tzunun, ubicado en la región de Mensabak, Chiapas, México, los mayas fortificaron una península según los principios de defensa en profundidad. En otras palabras, crearon zonas de fortificación para disminuir y detener un ataque. Las zonas consisten en barricadas exteriores y la colocación de estructuras dentro del terreno montañoso de la península/isla.

Adentro de esta comunidad fuertemente fortificada, la altura jugó un papel importante al brindar protección y mantener las diferencias de estatus. Dado su ventaja táctica, el pico más alto del sitio es un lugar de ritual y administración con su estructura más grande orientada físicamente hacia un templo que juntos formán un paisaje ritual. Debido a que el mantenimiento de paisajes rituales y lugares sagrados era fundamental para la autoridad élite entre los Mayas, el paisaje marcial local fue diseñado para brindar la mayor protección a lugares y símbolos de alto estatus. Semejante al pico más alto, un grupo apical cercano también reveló una ocupación de alto estatus en la cima. En general, se empleó la táctica de defensa en profundidad para proteger a los habitantes de Tzunun, con primacía estratégica dada a las ocupaciones de élite en las cimas del sitio. Mi análisis revela cómo la creación de un paisaje marcial, dio forma a la cultura local al perpetuar la desigualdad.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was conducted with the permission of Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONANP), and the community of Puerto Bello Metzabok, Chiapas. I would like to thank Justin Bracken, Kathryn Catlin, Juan Carlos Fernandez Diaz, Josué de Jesús Gómez Vázquez, Mark Hauser, Santiago Juarez, Rex Koontz, Daniela Koontz, Matthew Johnson, Kristin Landau, Little Leo, Luna, Rubén Núñez Ocampo, Joel Palka, Kathryn Reese-Taylor, Cynthia Robin, Ramesh Shrestha, and the National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping for their assistance in the development of this manuscript. The reported investigations were part of the broader Mensabak Archaeological Project (MAP), directed by Joel Palka (Arizona State University), and Adriana Fabiola Sanchez Balderas, Chief Executive Officer of Xanvil A.C. MAP, and was supported by a National Endowment for the Humanities (#196404) awarded to Palka. This research was also funded by a National Geographic Society Young Explorers Grant, National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (#1324585), a National Science Foundation Doctoral Dissertation Improvement Grant (#1546972) and National Science Foundation Social, Behavioral and Economic Sciences Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (#1715009) awarded to Hernandez. Last but not least, muchas gracias a la comunidad de Puerto Bello Metzabok por su apoyo y amistad durante muchos años de investigación colaborativa.