1 Overview

This case study presents innovative work by a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE) to use corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a key component of its business strategy in Kenya. AVIC International’s (“AVIC INTL’s”) core business is exporting Chinese machinery and vocational training curricula to enhance the availability of equipment in host countries and to build the capacity of local technical and vocational training institutions. Through active learning with stakeholders in Kenya, AVIC INTL has developed the “Africa Tech Challenge” (ATC) to host training and competitions for candidates from Kenyan technical and vocational institutes. This CSR project, first initiated in 2014, later became a signature CSR project for the company, one which was repeated annually and received Chinese government awards for companies’ overseas brand-building.

The case study shows how CSR can be an effective business strategy for Chinese SOEs operating in African states. Chinese SOEs have started to use CSR projects as a channel for gaining market access, building a positive image both in the host country and in Beijing, and cultivating and deepening ties with host country politicians, industry, civil society, and the (future) labor pool. The study also demonstrates how Chinese SOEs, over the course of overseas operations, have experienced a steep learning curve in host countries with this learning facilitated by SOEs’ interactions with stakeholders in the host country. It discusses how, despite structural asymmetry vis-à-vis China, African actors can actively shape the behavior of Chinese SOEs that are financially powerful and technically strong.

2 Introduction

Why do overseas Chinese SOEs engage in CSR initiatives?Footnote 1 How do SOEs effectively integrate CSR as part of their business strategy? These questions are particularly salient for SOEs working in host countries with relatively weak legal and social institutions to regulate corporate behavior. Global engagement by Chinese SOEs exposes them to new sets of local and international norms and practices that are frequently different from those in China. Many SOEs, during years of operations overseas, have experienced a steep learning curve in acquiring practices and norms from host countries, particularly in countries with sociopolitical contexts starkly different from that of China. CSR has become an area where SOEs can experiment with innovative practices that bring their corporate practices closer to the host country’s normative frameworks.

This case study examines AVIC INTL’s innovative approach of using CSR as a key business strategy in Kenya. It illustrates that in conditions of Sino-African power asymmetry, Chinese SOEs in Kenya learn from their interactions with host country stakeholders and adapt their operations. In 2014, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office rejected the standard approach to CSR as advocated by their headquarters in Beijing and instead initiated the ATC that later became a signature CSR project for the company. The ATC was continued annually and received awards from the Chinese government for effective overseas brand-building. What motivates AVIC INTL to allocate large budgets to this CSR project on an annual basis? Why and how did AVIC INTL create such innovative CSR activities in Kenya? And what was the role of Kenyan stakeholders in shaping AVIC INTL’s CSR initiative?

This case study draws empirical insights from the author’s direct participation in the ATC initiation stage as an early member of the China House, a Kenya-based NGO that participated in ATC’s design and implementation, in 2014. Additional empirical evidence was collected through interviews during multiple field trips to Kenya and China in 2017 and 2019 and follow-up telephone interviews in 2021 and 2022. The study also draws on secondary sources such as AVIC INTL’s CSR reports, internal documents, and email communications with stakeholders on the ATC projects.

The study is organized as follows. It starts by introducing the sociopolitical context of Kenya and Sino-Kenyan relations. Chinese companies operating in Kenya confront a starkly different sociopolitical landscape from their familiar context in China. The study then briefly discusses the Chinese government’s encouragement of Chinese companies, particularly SOEs, to use CSR as a way of overseas operational risk mitigation and it continues by describing AVIC INTL, its shareholding structure, its entry into Kenya, and its core business. The main subsection then elaborates on the initiation and development of ATC from an idea to AVIC INTL’s signature annual CSR project covering multiple African countries, and it concludes with a discussion of key points related to institutional learning, African agency, and the identity of Chinese SOEs as for-profit businesses, policy extensions of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and learning institutions to diffuse innovative overseas practices to China’s domestic business community.

3 The Case

3.1 Background on Sino-Kenyan Relations

Kenya is a lower-middle-income country. The country’s GDP per capita was US$2,007 in 2021,Footnote 2 and GDP per capita growth has averaged 1.3% over the past five years, above the regional average. In 2020, Kenya surpassed Angola to become the third largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa after Nigeria and South Africa, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). From 2015 to 2019, Kenya’s economy achieved broad-based growth averaging 4.7% per year, significantly reducing poverty (which fell to an estimated 34.4% at the US$1.90/day line in 2019).Footnote 3 Tourism in Kenya is the second largest source of foreign exchange revenue following agriculture. In 2020, the COVID-19 shock hit the economy hard, disrupting international trade and transport, tourism, and urban services activity. IMF evaluation shows that Kenya’s economic rank in sub-Saharan Africa dropped to seventh in 2021. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 further exposed Kenya’s economy to commodity price shocks, particularly as Kenya’s economy is vulnerable to the cost of fuel, fertilizer, wheat, and other food imports.Footnote 4

Kenya has one of the more vibrant media landscapes on the African continent, with professional and usually Western-trained journalists serving as watchdogs. The country’s media is highly competitive and diverse, with over 100 FM stations, more than 60 free-to-view TV stations, and numerous newspapers and magazines. Journalists in Kenya, like in many other African countries, have long been trained with Western curricula, which produces a media system that is “an appendage of the Western model” of journalism.Footnote 5 Kenya also has an active civil society organization (CSO) sector, and trade unions are active with approximately 57 unions representing 2.6 million workers in 2018.Footnote 6 Journalists and CSOs critically assess the operations of domestic and foreign businesses and politics.

In Kenya, like many other African countries, Chinese media reporting tends to be less appealing and less popular than news from Western media sources despite Beijing’s emphasis on soft power and discourse power.Footnote 7 In 2009, China’s central government committed US$6 billion to facilitate Chinese media “going out” and competing with Western media conglomerates.Footnote 8 In 2012, CGTN, the main Chinese global media station, opened its Africa headquarters in Nairobi and China Daily launched its Africa edition. Xinhua News Agency and China Radio International have also been active in their outreach to the continent. China even carried out media training programs for African journalists in China, with the hope that the journalists would portray China in a more favorable light upon returning home but with mixed results.Footnote 9 In fact, interviews and surveys with African residents found Chinese media outlets to be unappealing. Local interviewees were largely unaware of CGTN,Footnote 10 and a survey of young private sector employees in Nairobi showed that CNN, a US media outlet, was the most watched foreign media channel.Footnote 11

3.2 Kenya–China Relations

China established diplomatic relations with Kenya only two days after Kenya gained independence from the United Kingdom in December 1963. China was the fourth country to open an embassy in Nairobi. Bilateral relations gained momentum when President Daniel arap Moi came to power in 1978 and Deng Xiaoping in China pushed for “Opening and Reform.” The Sino-Kenyan relationship gained momentum with high-profile visits and agreements to promote trade, investment, and technology exchange, as well as military exchange.

China is Kenya’s largest trading partner and largest source of imports. In 2020, Kenya imported US$5.24 billion’s worth of highly diversified products from China, with textiles, chemicals, metals, electronics, and machinery representing the main sectors. In the same year, Kenya exported just US$123 million’s worth of products to China, predominantly minerals and agricultural products (see Figure 2.1.1). Kenya’s approach of exporting raw materials to China and importing manufactured products from China conforms to China’s bilateral trading pattern with many non-resource-rich African countries.Footnote 12

Figure 2.1.1 Kenya’s export basket, 2020

Kenya is the fourth largest destination of Chinese loans in Africa after Angola, Ethiopia, and Zambia. From 2000 to 2020, China extended US$9.3 billion of loans for transport, power, ICT, and other sectors.Footnote 13 The largest and most expensive project in Kenya supported by Chinese loans is the Standard Gauge Railway Phase I (US$3.6 billion) and Phase 2A (US$1.5 billion). Since 2017, however, concerns over Kenya’s debt sustainability and whether China uses debt to seek control over strategic assets such as railways and the Port of Mombasa have generated extensive debate in Kenya and internationally.

The two countries have starkly different sociopolitical systems. China is home to one of the world’s most restricted media environments with a sophisticated system of censorship.Footnote 14 The publication of the law on foreign nongovernmental organizations in 2017 and the 2016 legislation governing philanthropy significantly reduced CSOs’ access to funding from foreign sources and increased supervision and funding from the government. There is only one legal labor union organization, which is controlled by the Chinese government, and which has long been criticized for failing to properly defend workers’ rights.Footnote 15 Chinese companies operating abroad in highly different sociopolitical contexts such as in Kenya frequently find themselves stepping into unfamiliar situations such as environmental and community welfare activism, labor unions, and media watchdogs. Kenyan employees of Chinese SOEs may resort to strikes to force the management to negotiate on wage and benefits, issues that Chinese managers are ill-equipped to deal with and which are a source of tension that reveal large cultural and management style differences.Footnote 16 The sheer size and visibility of the multibillion-dollar projects that Chinese SOEs work on, with frequent visits from high-profile local politicians as well as Chinese and other international political celebrities, draw these projects into the media spotlight. Used to highly controlled media serving as a mouthpiece of the Chinese government, Chinese SOEs find themselves beleaguered by “biased” criticism in local and international newspapers and other outlets. As a result of these challenges, Chinese companies frequently find it challenging to adapt their operation to the Kenyan situation. One response is the defense mechanism of “keeping a distance with respect” (jing’er yuanzhi).Footnote 17

3.3 Doing CSR Overseas

The Chinese government has encouraged CSR domestically and published CSR regulations for overseas projects, yet implementation has been slow because these regulations are largely voluntary in nature and have weak implementation monitoring requirements. To coincide with the global expansion of Chinese companies and the ongoing evolution of the BRI, government agencies at both central and provincial levels issued 121 guidelines and regulations between 2000 and 2016, mostly voluntary, requiring Chinese companies overseas to perform CSR or improve environmental, social and governance (ESG) domestically and overseas.Footnote 18

In response to external criticism of Chinese companies’ overseas behavior, Beijing recalibrated the BRI and promoted new regulations to oversee its implementation.Footnote 19 For instance, in 2016, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce started to publish annual social and political risk assessments and held training programs for Chinese overseas investors. The Industrial and Commercial Bank of China published the first Belt and Road Green Bond at the Summit in 2019. The Environmental Protection Agency committed to training 1,500 officials in BRI countries and establishing technology exchange and diffusion centers along the Belt and Road.Footnote 20 However, the majority of these are also nonmandatory, and Beijing’s regulatory bodies cannot exercise effective control and oversight of all BRI activities conducted locally or abroad.Footnote 21

3.4 AVIC INTL and the TVET Project in Africa

China Aviation Industry Corporation (AVIC) is a central SOE specializing in aerospace and defense and headquartered in Beijing. It was founded on 6 November 2008 through the restructuring and consolidation of the China Aviation Industry Corporation Ι (AVIC Ι) and the China Aviation Industry Corporation ΙΙ (AVIC ΙΙ).Footnote 22 AVIC’s business units cover defense, transport aircraft, helicopters, avionics and systems, general aviation, research and development, flight testing, trade and logistics, assets management, financial services, engineering and construction, automobiles, and more. It is ranked 140th in the Fortune Global 500 list as of 2021,Footnote 23 and, as of 2021, has 1,003 subsidiary companies, including 63 second-level subsidiaries, 281 third-level subsidiaries, 340 fourth-level subsidiaries, 261 fifth-level subsidiaries, and 14 seventh-level subsidiaries, with 24 listed companies and 400,000 employees across the globe.Footnote 24

AVIC International Holding Corporation (“AVIC INTL”) is a global shareholding enterprise affiliated to AVIC. Also headquartered in Beijing, it has six domestic and overseas listed companies and has established branches in sixty countries and regions.Footnote 25 In 2008, AVIC INTL became an independent subsidiary company engaging in nonmilitary activities, including project planning, project financing management, export of electromechanical products, general contracting, operation, and maintenance of overseas engineering projects. AVIC INTL Project Engineering Company (“AVIC INTL-PEC”) was formally the International Projects Department under AVIC INTL and became a separate company in May 2011, also headquartered in Beijing. The company specializes in four main businesses: (1) people’s livelihood projects, including exporting Chinese mobile hospital equipment, vocational training equipment, container inspection system, buses, and so on; (2) energy engineering, procurement, and contracting, notably the Atlas Power Station Project in Turkey; (3) infrastructure construction, such as the rebuilding and expansion of a Kenyan airport project; and (4) industrial facility construction. The shareholding structure of AVIC INTL-PEC is illustrated in Figure 2.1.2.

Figure 2.1.2 AVIC INTL-PEC shareholding structure

AVIC entered Kenya in 1995 to export Chinese military aircraft to Kenya and established AVIC INTL Kenya representative office on 2 June 1995. Subsequently, AVIC INTL-PEC, AVIC INTL Beijing (covering businesses including cement engineering, petrochemical engineering, electromechanical engineering, and import and export of heavy equipment), and AVIC INTL Real Estate (newly established in 2014) were established in Kenya. When bidding for projects in Kenya, AVIC INTL-PEC, together with other subsidiaries, used the name of the parent company AVIC INTL because it had a bigger branding effect, but in reality these subsidiaries operate relatively separately, having offices in different compounds. AVIC INTL-PEC has engaged in three main projects: the National Youth Service (NYS) Phase I and II,Footnote 26 Technical, Vocational and Entrepreneurship Training (TVET) Phase I and II, and the Karimenu dam water supply project.Footnote 27

3.5 TVET Phase I

AVIC INTL’s TVET project was developed with the Kenyan Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (MOEST) and involves equipment provision and capacity-building for Kenyan technical and vocational training institutions. In 2008, a MOEST delegation visited China and raised a request to import Chinese machineries and training in support of Kenyan TVET institutions. In 2010, AVIC INTL signed a Memorandum of Understanding with MOEST for US$30 million for Phase I of the TVET project. The following year, the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) signed an agreement with the Government of Kenya, providing a US$30 million concessional loan in support of this TVET Phase I. The terms of this loan were set at 2% interest rate, twenty-year maturity, and a seven-year grace period. The loan was scheduled for semi-annual repayment between March 2018 and September 2030.

The purpose of the project was to establish ten vocational and technical institutes in Kenya and provide training to 15,000 students.Footnote 28 The implementation of the first phase of the project mainly focused on two parts: equipment supplies and course training. This includes providing electronic and electrical goods, mechanical processing, rapid prototyping experimental training equipment, diesel generator sets and corresponding spare parts, supporting facilities for ten affiliated colleges and universities, as well as providing college planning, professional settings, and course packages, including compiling textbooks, laboratory planning, teacher training, assessment and evaluation, integration of production and education, and academic exchanges.Footnote 29

3.6 TVET Phase II

In September 2013, AVIC INTL signed the TVET Phase II contract with MOEST at a cost of US$284 million.Footnote 30 This figure was later revised to US$167 million via Addendum No. 1 of the contract. The contract value was then further revised to US$159 million via Addendum No. 2 dated 25 May 2016, after the Government of Kenya opted to undertake the civil works itself, while leaving the supply, installation, and commissioning of the equipment as well as human capacity-building to AVIC INTL. According to the contract, AVIC sought to equip a total of 134 educational institutions and provide training across the country. It was stipulated that 1,500 teachers were to be sent to the field and 150,000 students were to be trained by 2020. Exim Bank’s approval for financing was pending for three years. It was not until 2017 that Exim Bank signed an agreement to provide an additional US$158 million of commercial loans for TVET project Phase II.

3.7 Challenges during TVET Phase I Implementation

By 2013, however, the imported equipment from TVET Phase I had not been used to its full capacity. A review of the project by Kenya’s Auditor General revealed that one university and nine technical training institutes had been supplied with electrical/electronic engineering, mechanical engineering, rapid prototyping manufacturing laboratories, and diesel generators, but a physical verification of the equipment in all of the ten institutes revealed that the equipment had not been utilized to full capacity and the generators had not been put to use.Footnote 31 AVIC INTL’s progress report to Exim Bank in June 2013 also recognized the limitation of existing infrastructure and the gap between Kenyan and Chinese higher education.Footnote 32 AVIC INTL’s then project manager Li explained these two points in detail.Footnote 33 First, many remote towns in Kenya cannot provide stable electricity, and unstable electric current risks damaging expensive equipment. Second, teachers in TVET institutions, even after weeks of training in China, were still not sufficiently skilled to operate the machines, let alone teach students. For the training, AVIC INTL partnered with Inner Mongolia Technical College of Mechanics & Electrics to design the curriculum and carry out the training, but the language barrier was a key obstacle. Chinese trainers from the college traveled to Kenya and taught through translators but misinterpretation and the need to use technical jargon resulted in misunderstandings.Footnote 34 AVIC INTL needed to show that Phase 1 was successful to secure follow-on finance. However, implementation of Phase 1 on the ground was far from successful with some brand-new machines purchased from China laying idle.

3.8 A CSR Innovation: Africa’s Tech Challenge

To secure Exim Bank’s funding approval for Phase II, AVIC INTL needed to show that Phase I was a success. An endorsement letter from the Chinese Economic Councilor in Kenya was a crucial step toward securing Exim Bank funding and Liu, the then deputy CEO of AVIC INTL, took a short trip to Kenya in late January 2014. There was a dinner meeting with Han Chunlin, the then Chinese Economic Councilor to Kenya. When Han asked about the progress of AVIC INTL’s projects in Kenya, Liu reported on the progress of TVET Phase II and reflected on the experience of implementing Phase I, which had been completed by the end of 2013. He said that, in Phase II, AVIC INTL would further commit, and explore possible solutions, to ongoing issues even beyond the contract framework, such as providing raw materials and manufacturing contracts to schools and ensuring that the products could be used in other AVIC INTL projects in Kenya. By then, the company had already signed a contract with MOEST regarding TVET Phase II and were applying to Exim Bank for a loan thus requiring the endorsement letter from the Economic Councilor.

This was also the time when AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters were considering conducting a CSR project in Kenya. The then AVIC INTL’s TVET project manager Li was also at the dinner that evening. Months later, he went on a trip to visit schools in the western provinces of Kenya with Isalambo S. Shikoli Benard, his counterpart from MOEST. On 21 February, on their way to Turkana, Li received an email from AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters in Beijing informing him of the headquarters’ interest in developing a CSR project in cooperation with the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation (CFPA). CFPA approached AVIC INTL headquarters in Beijing and proposed a CSR project featuring the provision of scholarships to African students to continue their study locally or in China. This was relatively easy to prepare and coordinate; CFPA already had rich experience of this type of corporate philanthropy in China. AVIC INTL headquarters allocated RMB 1 million (approx. US$16,000) for the Kenyan office to implement the project in collaboration with CFPA. AVIC INTL’s Kenyan office was selected because it was the first office to carry out an education-related program.Footnote 35 In the email, AVIC INTL headquarters indicated their plan to form a research team with the Corporate Culture Department and three managers from CFPA for a nine-day field trip to Kenya in March 2014 to carry out a feasibility study of this CSR project. Li was asked to coordinate with local stakeholders to prepare for this fieldtrip but was far from enthusiastic about CFPA’s proposal. During the seven-hour drive, Li and Benard discussed this scholarship project and Benard was equally unimpressed.

This prolonged driving trip was an ideal place for Li and Benard to brainstorm CSR project ideas. Benard’s team in MOEST had previous experience of hosting the “Robot Contest” and the winner was named “African Tech Idol.” The idea was to use robot assembly as an entry point to promote engineering and provide a forum for young engineers to display their creative works, exchange ideas, and promote engineering. Sponsored by Samsung, the fourth contest was to be held at TVET institutions.Footnote 36 Drawing on MOEST’s multiyear experience of successfully hosting the Robot Contest in cooperation with Samsung, Li and Benard borrowed this idea and applied it to AVIC INTL’s CSR project to host a technical skills competition using equipment installed by AVIC INTL. When they finally arrived at a village around midnight, Li emailed back to the senior management of AVIC INTL-PEC, copying in Liu, and warned of three difficulties in implementing the scholarship project including the recipient selection criteria, monitoring and evaluation, and most importantly, the corrupt nature of the client ministry:

The scholarship distribution has to rely on Kenyan Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, and the coordination process may induce corruption. Referencing to previous scholarship programs in cooperation with the Ministry, the scholarship tends to end up [more often] in the hands of some connected individuals than the most needed; or the money was simply divided up within the Ministry before they even reach the students.Footnote 37

In the same email, Li briefly outlined his discussion results with Benard on an alternative “Africa’s Tech Idol” project:

Name: Africa’s Tech Idol (tentative)

Potential candidates for the first season: Kenya Vocational and Technical College (about 30)

Two rounds of competition for the first season:

1. The preliminary round: machining competitions are held in five regions in Kenya and the top two in each region will be determined.

2. The final round: ten teams compete in machining at our workshop at Kensington University. We provide the design, and the team can choose their equipment, including ordinary and numerical control equipment.

The winning team will be rewarded:

1. Offered a production and processing contract on the spot.

2. Will be supported by our technicians in the factory.

3. We process raw material support.

4. A certain amount of project funding (in the form of sponsorship or angel funding) or equipment sponsorship, or both.Footnote 38

Sun and Qi (2017) had a subsequent quote from Benard explaining his attitude toward the traditional types of CSR and his enthusiasm toward the skills competition:

They [the AVIC International staff] were saying, “we could build a hospital…” I said, “All that is good, but it is being done by many people. But where you’ll have impetus: you’ve given us huge equipment, but the equipment is just here. We’re not utilizing it. So, if we have a competition to support this equipment, then really, you’ll be helping us as a country to build the confidence of our students that they can make things which can actually go out there.”Footnote 39

Benard drafted a project proposal for the creation of what eventually became the “Africa Tech Challenge” soon after returning from the Turkana trip.Footnote 40 In MOEST, Benard also sought higher administrative support from the Ministry. On AVIC INTL’s side, Li’s team sent the “Africa Tech Challenge” proposal back to Beijing for approval at the headquarters level. In comparison, the CFPA’s scholarship program gradually lost support from the AVIC INTL leadership.

In addition to MOEST’s experience in hosting skills competitions, Li also drew from the Japan International Cooperation Agency’s (JICA’s) extensive support of the Nakawa Vocational Training Institute in Uganda and also the experiences of Japanese companies in conducting CSR and other philanthropic projects – information shared via Li’s friend who was working in the Japanese Embassy in Uganda at the time.Footnote 41 Li’s friend was part of JICA’s Nakawa Institute project and, following his friend, he shadowed meetings with the project stakeholders in Uganda. When Li visited the Nakawa Institute, he was impressed to see that JICA’s malfunctioning vehicles were sent to Nakawa for maintenance. During the two decades of JICA’s cooperation with Nakawa, there was not only education but also a combination of “production and education” (chanjiao jiehe) projects in Nakawa, bringing business benefits to the institution in addition to training students. In his proposal to AVIC INTL headquarters, Li also cited the Toyota Academy and Huawei Training Centre in Kenya as successful examples of vocational training.

Upon initial confirmation from AVIC INTL headquarters of the idea of “Africa Tech Challenge,” Li and Mwangi, a Kenyan manager of AVIC INTL’s TVET project who used to study in China and speaks and writes Chinese fluently, developed the idea into a full concept note in March 2014. Mwangi’s family was well-connected in Kenya, and through her family network AVIC INTL managed to mobilize the then vice president (and president since 2023) William Ruto for the “Africa Tech Challenge” ceremony. Through his personal network, Li met the founder and CEO of China House, Huang, a Columbia University graduate and freelancing journalist who had created a Kenya-based CSO to help connect Chinese companies and Kenyan local communities. In his emails with AVIC INTL-PEC headquarters, Li mentioned China House and explored the possibility of contracting with China House to help with the development of AVIC INTL’s CSR project. Li wrote in his email to AVIC INTL headquarters:

Huang is very familiar with the media. At the time [of the competition], we will need the help of such talents in media public relations and writing various English reports… China House can recruit excellent summer volunteers to help us solve the labor shortage during the busiest season of AVIC INTL’s Kenya office.Footnote 42

Seeking to secure the first project, Huang’s friendship with Li led to a service contract between AVIC INTL and China House on the ATC in June 2014. China House recruited two full-time staff for the delivery of AVIC INTL’s contract. Among others, China House’s main responsibilities included (1) coordinating ATC stakeholders, including MOEST, public relations companies, social media, and the United Nations; (2) publicizing the ATC via China House’s own channels; and (3) providing a project evaluation summary report on the ATC’s effects to participants and media. Huang brought in his media connections and sensitivity to the ATC’s implementation and the involvement of China House was key to the development of the ATC.

Li convinced AVIC INTL headquarters to conduct the ATC as a machining skills competition in cooperation with MOEST. Li, with the help of the Ministry and together with China House, visited twenty-six out of forty-six TVET institutions in Kenya and received twenty-nine team applications, with three members in each team. Each school could nominate one or two teams with one advisor who was responsible for the organization of the participants. In the preliminary round, eighteen teams were selected and the top six then participated in the final competition. After twenty-three days of training, three winning teams were awarded US$100,000 in machine parts contracts and three individual awards with opportunities to continue education in China.Footnote 43 AVIC INTL subcontracted with the Inner Mongolia Technical College of Mechanics & Electrics to design the short training curriculum and flew two teachers from Inner Mongolia to Nairobi to train Kenyan candidates and prepare them for the competition. The ATC started in late July 2014 and the final competition was held on 5 September.

AVIC INTL’s Kenyan office developed the ATC and media relations strategy not through imposition or borrowing experience from Beijing headquarters but from the company’s interaction with stakeholders in Kenya. In addition to China House, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office also contracted with a Kenyan public relations (PR) company to run the ATC opening and award ceremonies and media engagement. Invited leaders from AVIC INTL and its parent company, the Chinese Ambassador, the Economic Councilor, the Kenyan Minister of Education, Science and Technology, and other government leaders attended the awards ceremony, which attracted wide media coverage. In fact, PR was a key component of ATC from the project design stage onward. PR costs represented 24% of the total ATC budget with expenses including PR company service fees, social media company service fees, and billboard rental and printing fees. AVIC INTL rented a billboard in Nairobi’s busy Harambee Avenue for multiple weeks. The ATC project evaluation report conducted by China House showed that the media influence of ATC included fifty-three media items at various stages of the ATC, including the opening and award ceremonies, during training, and the candidates’ recruitment. Nine out of the fifty-three pieces were from Chinese media groups in Kenya with the remainder from Kenyan and African media. Western media groups were absent.Footnote 44

The first ATC emphasized entrepreneurship and women’s empowerment as key themes beyond general skills training. The theme of entrepreneurship was implemented through ATC Talk, mimicking the format of a TED Talk. This idea emerged from a brainstorming session between Li’s team, China House, and the local PR company. The PR company invited successful Kenyan entrepreneurs and young leaders to communicate face-to-face with the students to share their entrepreneurial experiences and growth stories. In August and September 2014, three Kenyan entrepreneurs were invited to give talks to ATC candidates to create opportunities for candidates to interact with local businesses. Invited entrepreneurs shared their thoughts on topics such as “How to become an entrepreneur” by Samuel Kasera, CEO of Mutsimoto Motor Company, and “From student to entrepreneur: dream or reality” by David Muriithi, CEO of the Creative Enterprise Centre. The theme of women’s empowerment was addressed by making sure to give at least one female candidate the opportunity to study in China.Footnote 45 Charity, the only female winner among three candidates who were awarded a scholarship, continued her study at Beihang University in China and was featured in AVIC INTL’s short movie, A Kenyan Girl’s Dream to Become an Engineer.

The success of ATC resulted in AVIC INTL highlighting it as the company’s signature CSR project to be held annually. The ATC was an innovative idea for AVIC INTL, whose existing CSR projects were educational philanthropy, a signature project being a rural teacher training program named “Blue Chalk.”Footnote 46 It was also AVIC INTL’s only overseas CSR project. Each year, the ATC was featured in AVIC INTL headquarters’ annual documentary series, Glories and Hope. Although the revenue of the TVET project cannot compete with major construction projects from other AVIC branches, the ATC project was so unique that Li was awarded AVIC INTL “Best Overseas Employee.” The success of ATC Season I earned AVIC INTL wide media coverage in Kenya, enhanced client relationship with MOEST, and boosted Chinese domestic recognition.

Publicity for the ATC in China has not been as systematic as overseas in Africa where AVIC and China House’s connections were based. In explaining why the ATC’s overseas publicity is more important to AVIC INTL than domestic publicity in China, the current TVET project manager Yang explained: “We mainly target the overseas market, so domestic publicity is not very focused. At AVIC level, when they receive notifications from the government, AVIC sometimes requests us to report the ATC case.” The ATC project won the “2020 Excellent Case for Chinese Companies Overseas CSR Award,” an annual award jointly organized by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council Information Center, the China Press Office of the China International Publishing Administration, and the International Communication and Culture Center of the China Foreign Publishing Administration.Footnote 47 Utilizing its mobilization strength among university students in China, China House has also presented the ATC as a successful activity during policy conferences and student meetings.

Starting in Season III, ATC expanded beyond Kenya with teams invited from Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia. Cooperation with China House, however, finished. Since then, the ATC has become more closely aligned with AVIC INTL’s TVET project and women’s empowerment and entrepreneurship elements have not been featured.

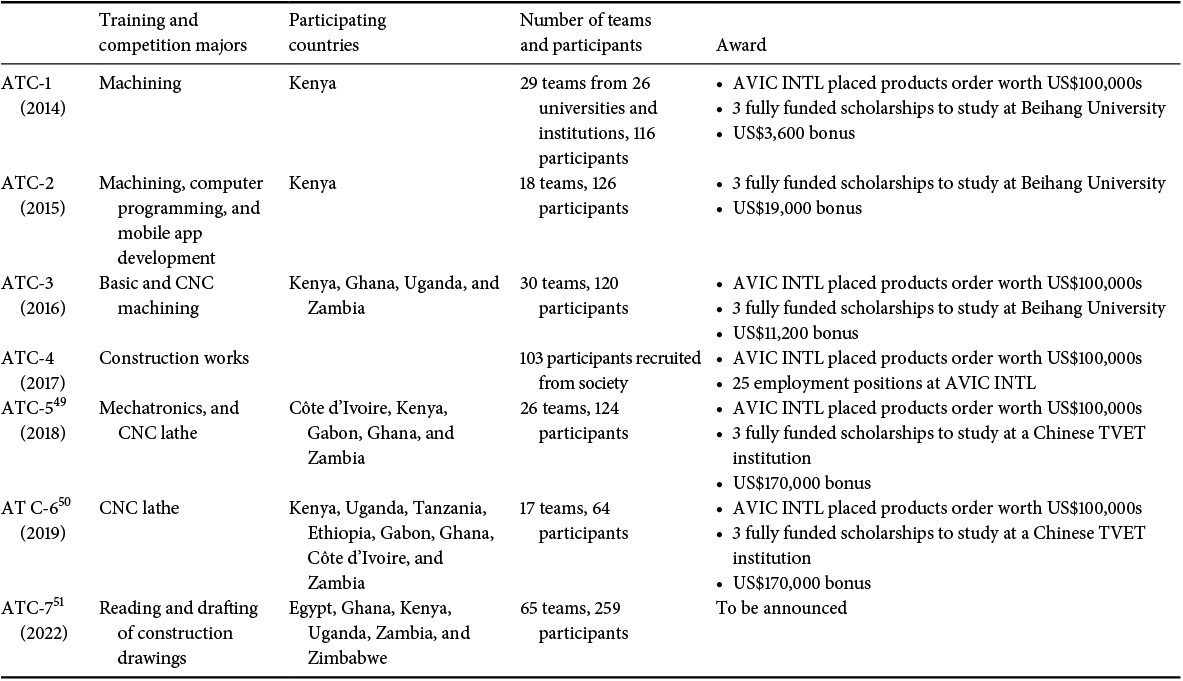

Since 2014, ATC has been held once a year, and as of 2019, it has successfully held six competitions (see Table 2.1.1). Each year, AVIC INTL allocates approximately RMB 3 million to the event.Footnote 48 Due to the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, the event was temporarily suspended, but in July 2022, after suspension for two years, ATC Season VII launched online. The training was also conducted online through a newly developed app that AVIC INTL developed to use for its TVET projects in response to the pandemic and expanding business globally. The preliminary round of ATC VII has expanded to 42 schools entering 65 teams from six countries, namely Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, and a total of 259 students.

Table 2.1.1 The seven ATC seasons and coverage

| Training and competition majors | Participating countries | Number of teams and participants | Award | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATC-1 (2014) | Machining | Kenya | 29 teams from 26 universities and institutions, 116 participants |

|

| ATC-2 (2015) | Machining, computer programming, and mobile app development | Kenya | 18 teams, 126 participants |

|

| ATC-3 (2016) | Basic and CNC machining | Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, and Zambia | 30 teams, 120 participants |

|

| ATC-4 (2017) | Construction works | 103 participants recruited from society |

| |

| ATC-5Footnote 49 (2018) | Mechatronics, and CNC lathe | Côte d’Ivoire, Kenya, Gabon, Ghana, and Zambia | 26 teams, 124 participants |

|

| AT C-6Footnote 50 (2019) | CNC lathe | Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire, and Zambia | 17 teams, 64 participants |

|

| ATC-7Footnote 51 (2022) | Reading and drafting of construction drawings | Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe | 65 teams, 259 participants | To be announced |

Yang, the current AVIC INTL’s TVET project manager, who was in charge of ATC, explained how this CSR project is being used to develop AVIC INTL’s main TVET business. ATC’s participating countries are usually the ones the company has already had TVET projects in or in which it plans to cultivate TVET cooperation:

We approached officials from the respective country’s Ministry of Education or their Vocational Education Department under the Ministry when we invited them to form teams to participate in the ATC, and for the award ceremony, we invited them over to Nairobi to attend. Similarly, we invite headmasters of TVET institutions in these countries. For each country, we have two official invitation quotas for the ATC award ceremony, and more Kenyan government officials are invited. At the third season of ATC, the current president-elect, William Ruto came.Footnote 52

This quote shows that the SOE smartly connects its CSR project to business development and market expansion. Although business development has not been made directly through the ATC, this platform is used to cultivate and maintain relationships with the leadership from TVET institutions and government officials of the target countries.

4 Conclusion

The ATC, AVIC INTL’s signature CSR project, is an example of a multinational company’s willingness to adapt to host country situations. First, AVIC INTL’s Kenya office demonstrated a learning curve with respect to CSR norms and practices in the host country. Over time, AVIC INTL developed an innovative and successful CSR project with an elevated PR strategy and aspects of gender equality and youth entrepreneurship. Second, the SOE’s project manager actively learned through interacting with a variety of stakeholders in Kenya through his personal and professional networks. Project manager Li incorporated expertise from Kenyan counterparts and drew on his knowledge of Japanese corporate practices and JICA projects to come up with tailored solutions appropriate for his project. MOEST’s successful multiyear experience of hosting the Robot Contest, in cooperation with Samsung’s CSR department and China House’s media relations and public engagement expertise, all contributed to the development and implementation of the ATC. Finally, the SOE’s internal structure may serve as a channel for the diffusion of good practices from field offices to Beijing headquarters and further spread to other Chinese companies through government promotion. Through AVIC INTL’s internal structures, information and experiences from the SOE’s field offices in Kenya were applauded by their headquarters in China and shared in internal meetings. The ATC as a case study also received an award from the Chinese government and was promoted to the wider SOE community.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

Upon completion of TVET Phase I, AVIC INTL identified the lack of usage of the machines they provided, which could potentially harm their success of securing Phase II funding from Exim Bank. Mediocre implementation on the host state side is a problem that extends well beyond the TVET case, and thus has broader significance for analyzing China–Africa projects. In the TVET case, substandard implementation was also the motivation for the company to innovate on a CSR project that could “train the trainers” to run the machines. To address the problem, AVIC INTL could have pursued a number of different strategies. For example, instead of initiating the ATC, another approach would have been for AVIC INTL to resort to litigation or other formal dispute resolution means. What are the legal merits for AVIC INTL’s claim should it want to sue the Kenyan government for not implementing its part of the contract? What are the potential risks for AVIC INTL if it pursued a legal rather than CSR route to solve the challenge? Do you agree with the company’s decision for not resorting to legal procedures?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

The ATC case raises two main questions with policy relevance. First, are CSR activities instruments of Beijing’s global soft power outreach or are Chinese SOEs making genuine progress toward localization and further internationalization? And are these mutually exclusive explanations? Arguably, Chinese SOEs, particularly their CSR activities, are part of Beijing’s broader soft power projection in Africa. Indeed, it is frequently perceived that Chinese SOEs, particularly given their state-owned nature, sometimes have broader, noncommercial aims providing a pivotal role in establishing connection between the Chinese government, local media outlets, and universities to promote a positive image of China in Africa. This case study, however, shows a CSR initiative developed by an SOE’s Kenyan subsidiary after the Kenyan project manager rejected the original CSR project proposal from the SOE headquarters. Following its success, the CSR project was then promoted by the SOE headquarters and the Chinese government as creating business development opportunities and as an example of corporate stewardship overseas. This case may thus show less a coordinated effort by the Chinese government in Beijing and more a localized learning endeavor by the SOE’s Kenyan subsidiary seeking to advance its business through an innovative and targeted CSR project. At the same time, in spite of the fact that the project was driven by local needs and interests, such facts are not to say that the Chinese government in Beijing could not then use the project for its own soft power benefits. Discuss these alternatives.

Second, is ATC an example of African agency or Chinese agency? Is China in Africa more precisely perceived as a global power exercising influence in small states? Or should we see this relationship as an interactive process where both parties have the agency to shape outcomes? We may emphasize the structural asymmetry between global economic and political strengths between smaller African countries and China, the world’s second largest economy and a rising power. In dealing with Chinese SOEs, we may perceive Kenyan bureaucrats, media, and CSOs as lacking the agency to shape the behaviors of Chinese SOEs to their benefit. An opposing perspective is to view Chinese SOEs’ activities in African countries, and in this case, AVIC INTL’s CSR initiatives in Kenya, as jointly shaped by Chinese managers and a variety of Kenyan actors. Discuss these diverging perspectives.

5.3 For Business School Audiences

AVIC INTL’s innovation underlines how CSR could help address several operational risks and opportunities for the overseas endeavors of Chinese SOEs and multinational corporations in general, particularly those operating in developing countries. What drives multinational companies’ CSR activities? The ATC case shows that in countries with relatively weak social and environmental regulations, CSR could help multinational companies earn the social license to operate and reduce compliance risks. In countries with strong socio-environmental protection laws that are strictly implemented, these legal regulations serve as a guidance for multinationals, particularly those that newly entered a market, to develop amiable community relations and avoid local pushback against their products and operations. In countries where the implementation of socio-environmental regulations is relaxed or even incomplete, how could companies use CSR activities to help them navigate community relations in host countries?

Second, the ATC case also demonstrates an opportunity for companies to strategically connect CSR and business development activities. How specifically did AVIC INTL manage to achieve this connection? In AVIC INTL’s case, the ATC’s success motivated the company’s leadership to further invest in the project and connect it to market expansion opportunities in neighboring African countries. In other words, this is a bottom-up and ad hoc connection between CSR and business development. What are options for companies to cultivate this connection? Could top-down design provide an alternative (or complementary) strategy?

1 Overview

This case study delves into the State Grid Corporation of China’s (SGCC’s) localization strategies within the Belo Monte hydroelectric project in Brazil, highlighting the challenges and learning experiences of Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in expanding their reach into Latin America. Over recent decades, Chinese SOEs have emerged as potential collaborators for Latin American countries in need of investment and technology for critical infrastructure projects. SGCC’s role in constructing the Xingu-Estreito transmission line for the Belo Monte hydroelectric plant stands as a prime example. This line, among the world’s largest and first to implement ±800kV ultra-high-voltage direct current (UHVDC) technology outside China, represents not only an engineering triumph for SGCC but also a significant business and legal accomplishment. The company adeptly navigated the complex Brazilian legal environment, addressing multifaceted regulatory, financial, and environmental challenges. While the Brazilian government has lauded the project for advancing energy security, it has also faced considerable criticism over socio-environmental issues. This case study, drawing on government and corporate documents as well as confidential interviews, examines SGCC’s approach to procurement, financial structuring, environmental licensing, and operational management in the context of these grandiose transmission lines.

Our company is from China, works in Brazil and gives back to the whole world; hence, the better its localization strategies, the more international it becomes.

The size of this project is the size of our people. It is grandiose. It is a grandiose power project. The best way to describe Belo Monte is this word: grandiose.

Our fish are gone, our village is gone, the blue of the lake we used to care for is gone. They violated our rights and threw us in the trash as if we were disposable.

2 Introduction

On 7 February 2014, executives at the SGCC headquarters in Beijing’s Xicheng District celebrated their successful bid to construct the Xingu-Estreito transmission line with a toast and smiles. Ten thousand miles away, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the celebration was a bit more boisterous. The victory in the Transmission Auction No. 011/2013 was a watershed moment for SGCC’s operations in Latin America. It marked its largest venture in the region and positioned the company as one of the largest foreign players in Brazil’s electricity sector. This achievement would be a triumph for any foreign company emerging in a market as competitive as Brazil’s. However, this example is particularly remarkable as SGCC had been operating in the country for less than three years – a short time for such a complex economic sector and jurisdiction.

When Cai Hongxian, a 46-year-old senior executive at SGCC, arrived in Brazil in September 2010, he faced the daunting task of leading the company’s most significant venture outside China. At that time, SGCC was already the world’s largest electricity company, holding assets worth US$3.9 trillion and providing power to more than 1.1 billion people in China (Figure 2.2.1 gives an overview of SGCC’s global assets as of 2021). However, the company had little experience investing overseas, having only previously ventured into the nearby Philippine market. Brazil was certainly the company’s biggest international challenge at the time – and its greatest economic opportunity. The country had a large consumer market, geographic characteristics similar to China’s, and was building stronger political ties with the Chinese government. Furthermore, Brazil was experiencing an economic boom, with a corresponding energy demand increase.

Figure 2.2.1 Overview of SGCC’s global assets, 2021

Conversion rate: RMB to US$ at 6.5 (Bloomberg, August 2021).

Cai was tasked with a clear goal: to make Brazil a successful case in SGCC’s emerging international portfolio, particularly since the board was interested in expanding into new markets. However, the means to achieve this goal were uncertain. When the executive arrived in Brazil, he exemplified SGCC’s general lack of knowledge about the country. He did not speak Portuguese, had a limited understanding of the complex regulatory environment surrounding the electricity sector, and was not familiar with the country’s business culture. Cai was accompanied by a small team of Chinese colleagues, SGCC’s technical expertise, and a blank check from headquarters – the Chinese board pledged to provide financial support for SGCC’s activities in Brazil as long as they were sound and profitable.Footnote 1 Nonetheless, Cai had to find a way to establish a successful company that could thrive in Brazil’s highly complex, competitive, but lucrative electricity market.

This case study explores SGCC’s foray into Brazil, drawing on a range of sources, including publicly available governmental, corporate, and regulatory documents, along with disclosed and undisclosed interviews with the company’s directors and legal advisors. The case study proceeds in five sections: the first provides an overview of the regulatory framework in Brazil that SGCC encountered in 2010; the second outlines the legal and corporate steps taken by SGCC upon entering the country; the third presents the Belo Monte hydroelectric project; the fourth examines the construction of the Xingu-Estreito transmission line; and the fifth evaluates the business aftermath of the line’s construction. Finally, the study concludes by highlighting SGCC’s successful localization strategies and discussing potential regulatory issues for the local government arising from the company’s expanding influence in Brazil.Footnote 2

3 The Case

3.1 Background: The Regulatory Framework of Brazil’s Electricity Market

Though SGCC made a swift entry into the Brazilian market, it was nevertheless a latecomer compared to other Western players. When Cai announced SGCC’s first investment in Brazil in mid 2010, that country’s electricity market was at the apex of a two-decade-long reform period. This era not only revolutionized electricity production and commerce but also led to the establishment of an interconnected grid system under a revamped regulatory structure, known as the National Interconnected System (Sistema Interligado Nacional).

This reform process can be traced back to the early 1990s. Facing a shortage of dollars stemming from a structural balance of payment crisis and an inability to meet foreign commitments, the Brazilian government embarked on a large-scale reform program under the neoliberal auspices of the Washington Consensus. Within the electricity market, the restructuring was grounded in the three principles of the British power grid model: promoting competition through staged segmentation; relinquishing the state’s monopoly and encouraging foreign direct investment; and repositioning the government from an active economic participant to a supervisory entity. Accordingly, the Brazilian government first segmented the electricity production chain into four stages: generation, transmission, distribution, and commercialization. Each segment was to be governed by its own set of regulations, standards, and supervisory institutions. Additionally, the government established three platforms for electricity trading: a system of public auctions to allocate concessions for each segment, a wholesale market for facilitating bilateral contracts between agents operating at different stages, and a secondary market for negotiating previously auctioned concessions.

Public and private companies, whether domestic or foreign, were allowed to participate in each segment either by securing new auctions or by acquiring existing concessions in the secondary market. The resulting “4-stages, 3-markets” framework was designed to mitigate risks of market control and supply chain verticalization, while assigning the Brazilian government the responsibility of managing the energy supply in line with its policy objectives.Footnote 3

The liberalization scheme brought about by these reforms significantly reduced public assets and redirected the state’s focus toward market regulation. The government created several new bodies to oversee economic activity across all stages, including the National Electric Energy Agency (Agência Nacional de Energia Elétrica, ANEEL), a quasi-independent regulatory agency responsible for supervising all stages and guaranteeing market competition. ANEEL also was tasked with coordinating public auctions for long-term energy concessions, where the bid is awarded to the company that offers the highest discount rate on the annual allowed revenue (receita anual permitida, RAP), that is, the lowest annual amount in fees.

The ensuing scenario marked a notable change in the nature of electricity production, transitioning from a predominantly state-owned economic activity to a decentralized, stringently regulated environment with a rising private sector. The market became fragmented, with successful privatizations resulting in the establishment of more than 280 companies in Brazil. Foreign participation became a cornerstone across all stages of the electricity production chain, surging from almost negligible to approximately 21% in the country’s installed capacity, 23% in transmission lines, and 52% in energy distribution.Footnote 4 In contrast to other Latin American economies such as Mexico and Paraguay, which primarily depend on state-led activities, Brazil boasts one of the most liberalized electricity markets in the region.Footnote 5 The majority of these companies are from Europe, North America, and, most recently, China.

Overall, the three reform pillars – competition, regulation, and private/foreign participation – effectively bolstered energy supply and resilience in the country while fostering market competition. From 1990 and 2022, the installed capacity in the country increased markedly from 49,760 MW to 206,451 MW, with the length of transmission lines correspondingly expanding from about 56,000 km to 165,667 km.Footnote 6 Brazil now ranks as the sixth-largest electricity producer worldwide, contributing 49.8% to Latin America’s total installed capacity.Footnote 7

Despite its progress, Brazil’s energy sector still faces critical challenges related to water availability and transmission distances. The heavy reliance on hydropower, accounting for 63% of Brazil’s electricity, renders the country vulnerable to climate-induced stresses, as highlighted by the severe 2020 drought.Footnote 8 The majority of energy demand, around 48.6%, is in the southeast’s urban centers, while approximately 70% of untapped hydropower resources are in the underdeveloped northern region – an area characterized by poor infrastructure, low population density, and a significant distance from consumer centers.Footnote 9 Developing projects in this region requires the construction of extensive transmission lines, which incurs efficiency costs and necessitates increased infrastructure investment.

3.2 The Company: SGCC Lands in Brazil

SGCC, a state-owned “profit-driven” utility company headquartered in Beijing, People’s Republic of China (PRC), operates under the oversight of the State Council State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, the body tasked with supervising China’s SOEs.Footnote 10 Established on 29 December 2002, SGCC emerged from an extensive reform within China’s electricity sector, which dismantled the former all-purpose China State Power Corporation (CSPC). This restructuring was driven by the policy of “grasping the large and letting go of the small” (zhua da fang xiao), adopted by the 15th Communist Party Congress in September 1997, with the aim of enhancing market competitiveness and fostering innovation through equity segmentation. The subsequent “Plant-Grid” reform led to the fragmentation of CSPC into five smaller generation groups and two grid companies, SGCC – which retained about 80% of CSPC transmission assets and the responsibility for orchestrating the general operations of the grids across the country – and the smaller China Southern Power Grid Company.

In the following years post-reform, SGCC established itself as the dominant force in China’s transmission sector, buoyed by public funding, easy credit access, market barriers for new entrants, and a vast consumer market. However, at the turn of the century, SGCC’s operations were predominantly confined within China, and few foresaw its venture into overseas investments. This direction shifted with the PRC’s “go out” (zouchuqu) policy in the early 2000s, encouraging outbound investment. Concurrently, SGCC’s business strategy expanded to encompass foreign markets, initially focusing on three objectives: enhancing technology for improved domestic outcomes, securing higher profits compared to the more price-restricted Chinese market, and strengthening its position within China’s political landscape.Footnote 11

As a result, in 2007, SGCC embarked on its first international venture in the Philippines. The company secured the operation of the national power grid during a privatization auction of the state-owned National Transmission Corporation (TransCo).Footnote 12 A consortium comprising SGCC and two Philippine companies, Monte Oro Grid Resources Corporation and Calaca High Power Corporation, clinched the bid with an offer of US$3.95 billion for a twenty-five-year license to operate TransCo. Within the newly formed National Grid Corporation of the Philippines, SGCC held a 40% stake and was able to appoint its chairman. SGCC hired Goldman Sachs to help with the deal.Footnote 13

In the following months, SGCC swiftly enhanced its corporate structure to better manage its emerging international portfolio. The restructured framework included the establishment of various subsidiaries, each tailored to oversee distinct aspects of its global activity.Footnote 14 These entities were not limited to but included (1) State Grid International Development Co. Ltd. (SGID Co.), a limited liability company organized under the laws of the PRC; (2) State Grid International Development Limited (SGID), a private company limited by shares organized under the laws of Hong Kong SAR; (3) International Grid Holdings Limited (IGH), a corporation organized under the laws of the British Virgin Islands; and (4) Top View Grid Investment Limited (TVGI), a corporation organized under the laws of the British Virgin Islands (BVI). IGH and TVGI are each direct wholly owned subsidiaries of SGID. SGID is a direct subsidiary of SGID Co., which is a direct wholly owned subsidiary of SGCC.

The Philippines venture highlighted both profits and challenges for SGCC. Initially harmonious, the relationship deteriorated due to events including the 2010 Manila hostage crisis and the 2011 South China Sea dispute. In 2012, the Philippines denied visas to twenty-eight SGCC executives and employees. Diplomatic efforts failed, and SGCC ceased further investments, while Monte Oro sold their shares to a local holding, OneTaipan. By 2015, the Philippines claimed technical self-sufficiency, leading to the exit of remaining SGCC experts. Although SGCC continued to receive dividends, its operational influence ended. Currently, no SGCC executive serves on TransCo’s board.

The Philippine experience highlighted the importance of political risk management and stability in international investments for SGCC. It provided valuable lessons that shaped SGCC’s more strategic and locally attuned approach to entering the Brazilian market. This new foray into Latin America was also informed by dialogues with the Chinese government, which equipped SGCC’s board with insights into global economic opportunities. This advice was crucial in light of the challenges other Chinese SOEs were encountering in their international ventures.Footnote 15

Subsequently, on 28 April 2010, SGCC announced its entry into Brazil by confirming the creation of State Grid Brazil Holding (SGBH), a privately held company focused on managing local equity interests.Footnote 16 SGBH was incorporated in Rio de Janeiro as a subsidiary of TVGI and IGH with a 0.0001% and 99.9999% interest, respectively. The incorporation was soon followed by the announcement of SGBH’s first investment in the country.

On 16 May 2010, the newly formed board confirmed the conclusion of negotiations to acquire seven transmission lines from the Spanish consortium Plena Transmissoras, led by Isolux, Cobra, and Elecnor, for US$989 million plus debt assumption. This deal also included a thirty-year license to operate approximately 3,000 km of the consortium’s transmission networks in Brazil. The deal involved Brazilian and Anglo-American law firms and was also supported by SGCC’s expanding in-house global legal team.Footnote 17 While the external firms addressed corporate and transactional legal issues, the internal team spearheaded legal research and played a pivotal role in shaping the investment strategy.

SGBH’s investment also coincided with a series of political agreements between Brazil and China. From 2002 to 2010, both governments signed various legal instruments, such as a Joint Plan of Auction and multiple Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs), highlighting economic opportunities and synergies. These documents frequently mentioned energy cooperation, with China expressing interest in Brazil’s electricity market.Footnote 18

Thus, when SGBH announced its entry into Brazil, it was celebrated by both presidents, Lula da Silva and Hu Jintao, for fulfilling the pledge of the Chinese government to invest in Brazil’s infrastructure gap. For SGCC, the Brazilian market seemed to be the right choice to bolster the company’s internationalization drive and it targeted Brazil for several reasons. The 1990s reforms in Brazil had gained international recognition, attracting an increasing number of foreign companies. Post-2008 financial crisis, European utilities, seeking capital, were keen to sell their local assets. Additionally, Brazil was anticipating a 4–5% annual growth in electricity demand from 2001 to 2021, further driven by Rio hosting the 2014 World Cup and the 2016 Olympics. As Cai stated in 2011: “Brazil is a politically stable country and has friendly relations with China … We were attracted to the Brazilian market due to its mature market operations mechanism, transparent decision-making, and orderly sectoral supervision.”Footnote 19

The 2010 acquisition proved to be just the beginning of SGCC’s plans for Brazil. Over the next few years, SGBH expanded its operations by acquiring other operational Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs) and participating in public auctions conducted by ANEEL. From 2011 to 2013, SGBH acquired five additional transmission lines (covering 1,960 km) from the Spanish group ACS for US$940 million and won four public auctions (covering 1,700 km) to construct new transmission lines in the country.

Despite financial support from the parent company for these operations, the initial phase was challenging for SGCC, as it had no previous experience operating in Brazil. The management team sent to the country, though well-versed in the market’s economic prospects, had minimal grasp of the complex regulatory landscape, the rigorous environmental licensing processes, and the robust labor protections involving a unionized workforce. As highlighted by a former SGBH director, the Chinese management, accustomed to a centralized political culture, “did not [initially] understand the regulatory, environmental, and labor intricacies of the country.”Footnote 20 As a result, the Chinese group employed various strategies to overcome the initial informational asymmetry and cultural gaps.

First, SGBH participated in public auctions as part of consortiums with Brazilian SOEs, a method used in three of the four initial auctions. In Auction No. 006/2011, SGBH secured a 51% majority stake in the Luziânia-Niquelândia substations system concession by forming a consortium with the state-run Furnas, offering a discount rate of 5.2% below the reference value. Similarly, in Auction No. 002/2012, SGBH joined forces with another Brazilian SOE, Copel, to obtain a 51% share in the Tele Pires transmission lines concession, including the Matrinchã and Guaraciaba projects, with substantial discount rates of 43.01% and 28%, respectively. In Auction No. 007/2012, SGBH collaborated with both Furnas and Copel to win a 51% share in the Paranaíba transmission lines project. As the SGBH Investment Director emphasized in 2012, the company’s strategy in Brazil at the time was centered on forming alliances with local companies, stating, “Our goal is to seek cooperation rather than competition.”Footnote 21

Second, through acquiring Plena Transmissoras and ACS, SGBH gained access to a skilled pool of professionals. Between 2010 and 2013, the company recruited several managers and workers from the acquired companies and the broader market, dramatically expanding its office in Brazil. One notable example was the hiring of Ramon Haddad, a former Plena Transmissoras professional widely recognized as a market expert, who later became the vice president of SGBH. As noted by a former SGBH director, “these acquisitions quickly provided operational infrastructure, but more importantly, valuable knowledge on how to navigate the Brazilian market in terms of regulations and professional networks with authorities.”Footnote 22

Over the next few years, the company consistently prioritized local expertise in its board and management roles. While the positions of chairman, CEO, and one vice president were held by long-standing SGCC employees, the other two vice presidents and senior directors were predominantly Brazilian. Of the initial 300 hires within the first three years, nearly all were locally sourced. By 2013, SGBH had also formed a dedicated in-house legal team, even incorporating Brazilian legal professionals who had assisted with the company’s initial M&As and public auctions.Footnote 23 This team grew over time, taking on most of SGCC’s in-house legal responsibilities in Brazil. Currently, they collaborate with local and, occasionally, foreign law firms for complex or specialized legal advice.Footnote 24

This move to localize both the operational and business decisions was a conscious one as Cai explained in 2013:

Given that we are a Chinese company entering a foreign market, we knew we had to adapt to the local culture and operational environment. We decided right from the beginning to bring twenty Chinese employees to Brazil to give us support through the process of adapting our Chinese culture to the Brazilian way of business. Such first steps are always tentative but we are here to stay and we are ready to do what is necessary to accomplish our targets.Footnote 25

Finally, during the initial period between 2010 and 2013, SGBH focused on strengthening its ties with local economic and political stakeholders, forging its own MOUs independently of the PRC government. A notable collaboration was formed with Brazilian SOE Eletrobras in 2011 during President Dilma Rousseff’s visit to China. This MOU facilitated interactions and technical knowledge-sharing between both electricity giants. Shortly thereafter, SGBH and Eletrobras deepened their partnership beyond political engagement, collaborating economically on the Chinese company’s most significant overseas investment at the time: constructing the first transmission line of the Belo Monte hydroelectric power plant, a grandiose dam marred by its socio-environmental impact.

3.3 The Project: The Belo Monte Hydroelectric Power Plant

In March 2010, ANEEL released the construction notice for the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, inviting bids under specific conditions. Accordingly, Brazil was set to build the third largest hydroelectric dam in the world, with an installed capacity of 11,233 MW across eighteen turbines. The proposed power plant, designed as a “diversion” or “run-of-river” facility, differed from traditional Brazilian hydroelectric plants that store river water. This design aimed to minimize the socio-environmental impact of the project.Footnote 26

The announcement of the Belo Monte dam project was greatly celebrated by then president Lula, whose administration revived the plan, originally conceived by Brazil’s military government in 1975. Lula’s administration advocated for the dam as crucial for Brazil’s energy security. However, civil society and environmental groups raised significant concerns. They criticized the project’s potential environmental and social impacts, particularly on Indigenous communities. Despite the design with reduced impacts, issues like water management and economic viability remained contentious.

Additionally, the dam was to be built in the Xingu River in the state of Pará, far from the country’s industrial region (Figure 2.2.2 provides an aerial view of the dam and its location). According to the transmission technology available in the country at the time, such long distances would result in significant losses during transmission to Brazil’s southeast. The most advanced transmission line in Brazil at the time was the Rio Madeira high-voltage direct current (HVDC) system. It consisted of two bipolar ±600 kV DC transmission lines, each with a capacity of 3,150 MW, and an approximate loss rate of 11%.

Figure 2.2.2 The Belo Monte dam and its location in Brazil

Some of the concerns surrounding the project proved to be valid. The dam led to the displacement of several communities and significantly altered the region’s environmental conditions.Footnote 27 Fluctuations in river flow affected power production, with the dam’s guaranteed minimum capacity set at 4,571 MW, approximately 39% of its maximum capacity (Figure 2.2.3 gives annual average production). Furthermore, the consortium that won the bid for the hydroelectric plant, comprising several prominent Brazilian companies, faced numerous corruption allegations and environmental disputes in federal courts. These challenges delayed the dam’s completion by fourteen months and doubled its total cost from approximately US$9 billion to US$18 billion.Footnote 28 Despite these issues, the initial fears of energy loss did not materialize, as Brazil was on the brink of witnessing the construction of one of the world’s largest UHVDC lines.

Figure 2.2.3 Belo Monte dam’s daily average energy production, 26 February 2016 to 30 December 2023 (median megawatts, MWmed)

3.4 The Line: Xingu-Estreito

The construction of the Belo Monte dam started in 2011, but only two years later the auction notice for its transmission lines was made public – a short but crucial period for the lines’ design. ANEEL produces feasibility studies before officially launching a project via its Energy Research Office (Empresa de Pesquisa Energética, EPE), which details the expected technicalities required in each project. In 2007, EPE published the first studies for a transmission line connecting the Belo Monte dam to the national grid. These studies proposed using an HVDC of ±600 kV, similar to that seen in Rio Madeira.

In 2011, EPE conducted new feasibility studies. This time it recommended using a UHVDC system consisting of two bipolar ±800 kV DC transmission lines, each with a capacity of 4,000 MW. UHVDC technology offers lower transmission costs and higher efficiency for transmitting very high power over long distances. However, at the time, the technology for this voltage level was not only unavailable in Brazil but only used in one place in the world: China.

On 19 December 2013, the auction notice for the Xingu-Estreito line was then published, confirming the use of UHVDC. When the offers for the construction and thirty-year use concession were opened on 7 February 2014, a consortium composed of SGBH and two Eletrobras subsidiaries, Eletronorte and Furnas, won the bid to Auction No. 011/2013. The three companies offered US$217 million of annual revenues to build and operate the lines, a 38% discount rate to the notice threshold. Chinese officials noted that SGCC’s competitive bid was enabled by its ability to source significant equipment from China.Footnote 29

In March 2014, the three companies then established an SPV named Belo Monte Transmissora de Energia (BMTE) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. SGBH held a majority stake of 51% in BMTE, with Eletronorte and Furnas splitting the rest equally. The company’s governance structure balanced Brazilian and Chinese influences, featuring an evenly shared presidency and board with three members from each country. Senior management roles were jointly held, pairing a director and a deputy for each area, representing both nationalities.

The partnership between SGBH and Eletrobras proved effective for handling the complexities of the Xingu-Estreito project. Despite SGBH’s growing familiarity with Brazil, this project posed larger technical, environmental, economic, and political risks. The planned transmission line, traversing sixty-five municipalities, four states, and three biomes in Brazil, presented a challenging terrestrial landscape. The legal complexities were even more daunting, requiring billion-dollar funding, negotiations with numerous landowners, and adherence to strict environmental standards. Collaborating with Eletrobras, Brazil’s largest energy player, presented an advantageous opportunity. SGCC brought state-of-the-art technical expertise, while Eletrobras contributed extensive local knowledge of Brazilian regulations and authorities. As an SGBH former director aptly put it, “This was a successful business strategy from SGCC to adapt to Brazil, mitigate risk, and accelerate learning.”Footnote 30

Although the companies collaborated, each had a specific role in particular aspects of the venture. SGBH managed the financial side and appointed the Financial Director to BMTE. Eletronorte was in charge of obtaining environmental licenses and naming the Environmental Director. Furnas handled the technical design and appointed the Technical Manager. Furthermore, Eletrobras engaged in shaping public opinion through a media campaign to address ongoing criticisms of the Belo Monte project.

A distinctive feature of this management structure was the implementation of a “shadow management” system. In this arrangement, whenever a Brazilian professional held a managerial role, a Chinese deputy was assigned to work alongside them. This Chinese deputy closely collaborated with the Brazilian manager, providing insights and relaying important information back to the Chinese headquarters. As explained by a former director: “Every senior executive at SGBH had a Chinese shadow at his side. And this Chinese shadow made reports to the Chinese headquarters on the matters dealt with. It was a way that the Chinese found to learn about the Brazilian operation in practice.”Footnote 31

In legal matters, the SGBH in-house team led operations for BMTE in conjunction with teams from Eletronorte and Furnas, maintaining close collaboration with the Chinese management, the global SGCC legal team, and external law firms, especially for intricate tasks such as debenture issuance, audits, and labor- and tax-related issues. While ultimate decision-making authority rested with the Chinese management, the Brazilian legal team enjoyed significant autonomy in handling local affairs. As one SGBH lawyer noted, “Brazilians were at the forefront of all legal operations, reporting to Chinese managers. Direct interactions with Chinese executives were rare.” A former director further explained, “Cai had the final say, but our legal team had substantial independence in determining the best strategies for matters involving concessions, public bids, or landowner negotiations to achieve the company’s economic goals.”Footnote 32