Introduction

The delegation of policy implementation to a non-majoritarian executive can result in policy drift (Epstein and O’Halloran Reference Epstein and O’Halloran1994; Franchino Reference Franchino2007; Huber and Shipan Reference Huber and Shipan2002; Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015). This has sparked a rich literature on the various control mechanisms that legislators can deploy to decrease such a drift. These include ex ante amendment of executive acts before their adoption or their ex post veto to override (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2017). However, we still know little about how the use of different control mechanisms affects the subsequent compliance outcomes. A recent change in the European Union (EU) treaties allows us to study this question by providing the EU legislators with distinct instruments for delegating implementation powers to the European Commission, which are subject to different levels of legislative control.

By examining the compliance of member states with the different types of executive (or Commission) acts, this study addresses the broader literature on the effectiveness of various mechanisms of controlling executive drift. It further adds to both studies on member states’ compliance with EU legislation and EU bureaucratization. Despite the growing number of executive acts, we have a limited understanding of how member states comply with Commission measures. Existing studies have compared compliance with EU secondary legislation (i.e., policies adopted by the EU legislature composed of the Council of the EU (Council) and the European Parliament [EP]) and tertiary legislation. They find that tertiary acts are generally easier to implement than secondary acts (Börzel Reference Börzel2021; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Luetgert and Dannwolf Reference Luetgert and Dannwolf2009; Mastenbroek Reference Mastenbroek2003) because member states face fewer domestic compliance costs.Footnote 1 To our knowledge, no study has systematically analyzed the determinants of member states’ compliance with different types of Commission acts. This is a major gap in the literature given the increasing volume of tertiary legislation and the political debates surrounding its adoption at the EU level (Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015; Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020).

Indeed, most EU policy instruments nowadays are not adopted by EU legislative institutions but by the executive, that is, the European Commission. The Council of the EU and the EP empower the Commission to adopt administrative rules to clarify, update, and supplement EU legislation. These tertiary acts have tremendous consequences for the member states as they determine how the EU policies are implemented by national governments. Thus, they enable the Commission to alter the spirit of EU legislation without necessarily taking on board the preferences of all legislators, which the Commission has incentives to do (Ershova et al. Reference Ershova, Yordanova and Khokhlova2023; Williams and Bevan Reference Williams and Bevan2019; Yordanova et al. Reference Yordanova, Aleksandra Khokhlova, Schmidt and Glavaš2024). Therefore, as in most political systems, delegation of powers to the EU executive is accompanied by control procedures that seek to keep it in check with the legislature’s preferences. This has historically been achieved through comitology: a system of committees of member state policy experts, involved in shaping and approval of the Commission’s so-called implementing acts (Article 291 TFEU) (e.g., Bergström Reference Bergström2005; Blom-Hansen Reference Blom-Hansen2011; Héritier Reference Héritier2012). However, the Lisbon Treaty (2009) transformed the legislative control over executive measures by introducing a new type of Commission measures, that is, delegated acts (Article 290 TFEU). As opposed to implementing acts, delegated acts are not subject to formal scrutiny in comitology committees, and national experts do not have formal rights to shape or amend them (although they can play an informal advisory role). Instead, through the Council, member states can only veto delegated acts, a nuclear option that may cause legislative failure or delay.

This leads us to the following competing expectations regarding member states’ compliance with delegated versus implementing acts. On the one hand, if member states’ preferences are not being taken into consideration in the formulation of delegated acts, this should lead to lower compliance with delegated as compared with implementing acts. This should be further shaped by the level of preference divergence between member states and the Commission. On the other hand, there are reasons to believe that member states have retained control over the content of delegated acts. First, the Commission continues to consult member states informally (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2012; Hardacre and Kaeding Reference Hardacre, Kaeding and Hardacre2011; Ritleng Reference Ritleng2015). Second, member states, represented by the Council, still control the delegation of implementation powers to the Commission in secondary legislation, alongside the EP. Thus, they can block the use of delegated acts on controversial issues, on which they expect policy drift by the Commission. In this case, we should observe, respectively, no differences in member states’ compliance with the two types of Commission acts or even less compliance with implementing acts (if they cover more controversial issues). Finally, we expect member states’ bureaucratic capacities to be more relevant for explaining compliance with delegated acts than with implementing acts if the former cover more complex issues.

We test our contrasting expectations using an original dataset of all delegated and implementing directives adopted by the Commission in the period between the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009 and the end of 2016. The dependent variable on member states’ compliance is measured through transposition delays and, as a robustness check, infringement cases. We find that member states are less likely to comply with implementing acts relative to delegated acts. We explain these findings with the use of delegated acts to supplement or amend legislation only on non-controversial issues, which is in line with the spirit of the Treaty. In other words, the available executive instruments offer member states their desired oversight mechanism (amendment and/or veto).

In the following section, we offer an overview of delegated and implementing acts and discuss the implications of their use for member states’ influence in policymaking. We proceed with a review of the theoretical literature on compliance with EU law. Upon formulating hypotheses on the extent and determinants of member states’ compliance with different types of tertiary acts, we describe our research design, analysis, and findings. We conclude with a discussion of the results and their implications for the alleged bureaucratization of EU policymaking and the effectiveness of legislative oversight tools more generally.

The bureaucratization of EU policymaking: delegated versus implementing acts

Nearly 80% of EU legislation constitutes executive acts, adopted by the Commission (Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015, p. 788), which serve to specify, update, and implement European legislation. Member states have historically exercised control over the Commission’s adoption of executive acts through a comitology system, which entails a system of committees of member states’ experts that “decides whether to approve the Commission’s acts or to refer them to the Council for further scrutiny” (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2012, p. 939). The comitology system was created in the 1960s in response to member states’ reluctance to delegate extensive powers to the Commission (Bergström Reference Bergström2005; Blom-Hansen Reference Blom-Hansen2008). It currently applies to implementing acts (Article 291 TFEU). These are acts that the Commission adopts, for which the EU legislators confer to it implementing powers in secondary legislation. They serve the purpose of setting uniform conditions for implementing the respective secondary acts in the member states through national legal measures. The member states oversee the Commission through various comitology committees, set up by the legislators and composed of a representative from each member state and a Commission official chairing. They provide a formal opinion, usually in the form of a vote, on the Commission’s proposed measures, which is binding depending on the mechanisms of member state control of the Commission’s exercise of implementing powers laid down by the EP and the Council (Article 291.3).

The Lisbon Treaty transformed the system of executive policymaking by introducing another type of executive acts, so-called delegated acts (Article 290 TFEU), which transfer powers to the Commission to amend or supplement “non-essential elements of secondary legislation” (i.e., measures of general scope but not part of the core text of the legislative act itself). The EU legislature (the EP and the Council) determines within the text of the secondary act it adopts the delegation powers of the Commission act, specifying the objectives, content, scope, and duration, including whether the Commission should amend (modify or repeal non-essential elements while complying with the essential elements of the secondary act) or supplement (develop in detail non-essential elements, complying with the entirety of the secondary act) the secondary act (European Court of Justice [ECJ] 17 March 2016, C-286/14). In its adoption of delegated acts, the Commission is held to account only ex post by the EU legislators, instead of being subject to ex ante control by the traditional committees of member state representatives in comitology (Article 290 TFEU). In particular, the Council and the EP share the powers to revoke the delegation or to object to the adoption of a specific delegated act within a time limit set by the secondary legal act, for which the EP acts by absolute majority (of its component members) and the Council by a qualified majority. However, member states do not have formal powers to scrutinize the Commission’s delegated acts via national experts as the comitology system does not apply to those acts. The legislators are left with a take-it-or-leave-it choice and no positive amendment power. Compared to implementing acts, this “reduces the ex ante control by the Union legislators” and “appears to indeed satisfy the Commission’s demands to enhance its executive autonomy” (Schutze Reference Schutze2011, p. 686).

Most research on the new system of delegation has so far analyzed its development, control, and preferences of institutional actors over the use of delegated or implementing acts (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2017; Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020). Recent studies have mostly analyzed the interactions between the Commission and the comitology committees in the case of implementing acts (Finke and Blom-Hansen Reference Finke and Blom-Hansen2022; Pasarin et al. Reference Pasarin, Dehousse and Plaza2021). Scholars generally agree that the distinction between delegated and implementing acts is not straightforward, and the use of either type depends on political considerations (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2012, Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2016; Christiansen and Dobbels Reference Christiansen and Dobbels2013a; Christiansen and Dobbels Reference Christiansen and Dobbels2013b). The ECJ confirmed this when the Commission challenged the legislators’ decision to convert to implementing rather than delegated powers conferral in one of its legislative proposals, ruling that ultimately this choice is to be made by the EU legislators (the EP and the Council), pursuant to the respective Treaty articles, while judicial review is limited to manifest errors of assessment.Footnote 2 It remains unclear if the EU legislators manage to tailor this choice in a way that avoids policy drift of executive acts and, as a result, how member states comply with different types of tertiary acts in general.

Do member states have less control over delegated acts relative to implementing acts?

There are different views on the relative level of control exercised by the Council and, thus, the member states over delegated as compared with implementing executive acts. The formal rules and the preferences of the Council indicate that it has less control over executive decisions in the system of delegated measures for several reasons.

Firstly, the Council only has the nuclear option to either prevent a delegated act from being adopted or revoke the delegation altogether but no formal ex ante powers to substantively amend delegated acts in a way that reflects the preferences of member states (Christiansen and Dobbels Reference Christiansen and Dobbels2013a; Christiansen and Dobbels Reference Christiansen and Dobbels2013b). Moreover, the Council faces significant constraints in exercising its veto powers. Depending on the provisions in the basic legislative act, it has limited time to formally voice its objections (between one and six months). Formal vetoes also need to be supported by a relatively large majority of member states (a qualified majority (QMV) in the Council consisting of at least 72% of its members representing at least 65% of the EU’s population). Because of the high voting thresholds, some scholars contend that the member states have limited influence under the new system of delegated acts, as they can effectively block executive policymaking only when many member states express disagreement with the Commission’s draft measures (Kaeding and Stack Reference Kaeding and Stack2015). In line with these arguments, Siderius and Brandsma (Reference Siderius and Brandsma2016) expect and find that the Commission is more eager to build support and accommodate member states’ preferences when drafting implementing acts than in the preparation of delegated acts. Consequently, the authors conclude that “Because the Council will almost never veto delegated acts, there are fewer incentives for the Commission to meet the preferences of all Member States” (Siderius and Brandsma Reference Siderius and Brandsma2016, p. 1277).

Secondly, the alleged loss of power of member states in delegated acts is also reflected in the preferences of the Council. There is a broad agreement in the literature that the Council generally favors strict comitology rules (Blom-Hansen Reference Blom-Hansen2011; Dogan Reference Dogan1997; Franchino Reference Franchino2007, pp. 283–5; Hardacre and Kaeding Reference Hardacre and Kaeding2010). After the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty, the Council has continuously insisted on the use of implementing acts or the ordinary legislative procedure during legislative negotiation whenever the use of delegated acts is debated (see Christiansen and Dobbels Reference Christiansen and Dobbels2013a).

However, the loss of formal powers by the member states may not have any practical implications for member states’ compliance. Firstly, member states can still exert influence over delegated acts through informal consultations. Brandsma and Blom-Hansen (Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2012) argue that member states succeed in incorporating their preferences in delegated acts due to informal arrangements that commit the Commission to systematically consult national expert groups when drafting delegated acts (Council 2011; Hardacre and Kaeding Reference Hardacre, Kaeding and Hardacre2011). These arrangements have been described as “reintroduction by the backdoor of the committee regime” (Ritleng Reference Ritleng2015, p. 255). Given that informal consultations do not have strict time limits, member states can delay the adoption of delegated acts. Secondly, the Council can pre-empt bureaucratic drift by blocking the use of delegated acts ex ante. The Council and the EP need to first confer powers to the executive to adopt delegated acts before it is even possible for the Commission to draft such measures (Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020). However, the Council may not agree to do so when it fears policy drift from a runaway Commission. Thus, the Council can obstruct the adoption of delegated acts or agree to their use only in relation to the most technical and non-controversial issues.

In sum, there are competing arguments about whether delegated acts diminish member states’ influence over executive policymaking in practice. Moreover, any such loss of control would only matter when there is a threat that the Commission would pursue policies that are not congruent with the member states’ substantive preferences. Unfortunately, we lack systematic information about the Commission’s and member states’ preferences to evaluate the risk of executive drift regarding every (potential) delegated act. Whereas recent studies measure the member states’ opposition to Commission’s draft implementing proposals (Finke and Blom-Hansen Reference Finke and Blom-Hansen2022; Pasarin et al. Reference Pasarin, Dehousse and Plaza2021), there is limited information about opposition to delegated acts. However, we argue that member states’ (in)ability to influence the content of the Commission’s acts should be reflected in their subsequent (non-)compliance with these acts. Thus, we build our expectations based on the literature on EU compliance.

Research on compliance with executive measures

Research on EU implementation has shown that EU’s tertiary acts adopted by the Commission are less likely to experience compliance problems relative to secondary legislation (Börzel Reference Börzel2021; König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Luetgert and Dannwolf Reference Luetgert and Dannwolf2009; Mastenbroek Reference Mastenbroek2003). On the one hand, several studies argue that politically sensitive issues are unlikely to be delegated to the Commission level (Kaeding Reference Kaeding2006; Mastenbroek Reference Mastenbroek2003). In addition, Commission directives primarily modify earlier Community legislation (König and Luetgert Reference König and Luetgert2009; Luetgert and Dannwolf Reference Luetgert and Dannwolf2009; Steunenberg and Rhinard Reference Steunenberg and Rhinard2010). As a result, these acts are “arguably easier to incorporate into national legislation” than policies adopted by the EU legislative institutions (Luetgert and Dannwolf Reference Luetgert and Dannwolf2009, p. 313). On the other hand, the assumption that Commission directives are non-controversial is not straightforward, as delegation also occurs to prevent policy drift by national administrations during the implementation process (Borghetto et al. Reference Borghetto, Franchino and Giannetti2006). Thus, executive measures reduce domestic compliance costs by allowing member states to circumvent domestic opposition to potentially contentious issues (Börzel Reference Börzel2021; Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015). In other words, executive measures deal with inherently contentious issues that can be politicized by domestic actors involved in the implementation process. Empirical findings also suggest that Commission measures “sometimes include difficult cases”, which create obstacles to national administrations in the long run (Haverland et al. Reference Haverland, Steunenberg and Van Waarden2011: 284). Related to this, non-compliance with tertiary acts has not been a rare occurrence since the adoption of the Lisbon Treaty. For example, our dataset shows many transposition delays and infringement cases against member states. Of all the 2352 directive-member state dyads in the dataset, transposition delays occurred in 547 dyads (or 24%, of which 163 related to delegated acts). The Commission initiated infringement proceedings against member states in 464 dyads (or 20%, of which 185 related to delegated acts). Thus, non-compliance with EU’s tertiary legislation does not constitute a trivial problem and merits attention. This is exacerbated by the fact that most EU legal acts are in fact executive measures that are unilaterally adopted by the Commission (Brandsma and Blom-Hansen Reference Brandsma and Blom-Hansen2016; Siderius and Brandsma, p. 1265).

Expectations about member states’ compliance with delegated versus implementing acts

To formulate expectations about the determinants of member states’ compliance with delegated and implementing acts, we follow established approaches, broadly divided into two groups: capacity-based and preference-based explanations.

First, preference-based explanations (also known as the “enforcement approach”) suggest that states voluntarily choose to defect from international agreements if the perceived benefits of doing so exceed the costs of non-compliance (Downs et al. Reference Downs, Rocke and Barsoom1996; Fearon Reference Fearon1998). The benefits of non-compliance could be either alternative priorities (given that compliance entails committing scarce resources that could be allocated to other uses) or a misfit of policy preferences with the contents of the adopted agreements. The costs of non-compliance refer to the probability of detection, perceived reputation losses, and the threat of sanctions that could be imposed on law-violating governments (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann, Panke and Sprungk2010; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002; Zhelyazkova et al. Reference Zhelyazkova, Kaya and Schrama2016). To measure policy preferences, scholars generally focus on government support for EU integration or government policy preferences regarding EU directives (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Torenvlied and Arrequi2007).

The second approach, by contrast, presents non-compliance as the result of states’ capacity limitations as well as complexity and ambiguity of EU legislation (also known as the “management approach”). Capacity limitations arise when a government lacks the necessary resources or cannot garner sufficient political and bureaucratic support to enforce an international agreement (Chayes and Chayes Reference Chayes and Chayes1993; Tallberg Reference Tallberg2002). Applied to the EU context, it is argued that national administrative constraints prevent or slow down the implementation of EU policies by national bureaucrats (Börzel et al. Reference Börzel, Hofmann, Panke and Sprungk2010; Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Torenvlied and Arrequi2007; Zhelyazkova et al. Reference Zhelyazkova, Kaya and Schrama2016). Among such constraints, government and bureaucratic inefficiency, poverty, and corruption are expected to affect member states’ capabilities to process, interpret, and adapt European rules into national settings (Jensen Reference Jensen2007; Mbaye Reference Mbaye2001; Perkins and Neumayer Reference Perkins and Neumayer2007).Footnote 3

Following enforcement and management approaches, respectively, we expect both preference divergence and state bureaucratic capacities to shape the implementation of tertiary acts. However, we argue that they will have different effects, depending on assumptions about member states’ de facto control (formal and informal) over different types of tertiary acts.

We depart from four alternative assumptions to derive our expectations: (1) member states exert less de facto control over delegated acts than over implementing acts; (2) member states exert equal control over the two types of acts; (3) member states grant the Commission the power to adopt delegated acts only in relation to (3) non-controversial issues or (4) highly complex issues. The assumptions and the respective hypotheses we derive from them are summarized in Table 1 and discussed below.

Table 1. Assumptions and hypotheses on member states’ de facto control over and the level of compliance with delegated acts

Firstly, if member states have less de facto (formal and informal) control over the Commission for delegated acts, this could mean that delegated acts do not meet the preferences of (at least some) member states to a greater extent than implementing acts. Consequently, member states whose policy preferences have been ignored during the decision-making process would have incentives to deviate at the implementation stage. This process is often referred to as “opposition through the backdoor” because non-compliance with EU policies can be seen as the continuation of opposition by other means (Falkner et al. Reference Falkner, Hartlapp, Leiber and Treib2004; Thomson Reference Thomson2010). Thus, if member states are indeed unable to amend policies in a way that fits their preferences in the system of delegated acts, on average, we should observe relatively more compliance problems related to delegated than to implementing acts.

H1: Member states are more likely to experience compliance problems in relation to delegated acts than to implementing acts.

Under the same assumption, non-compliance problems with delegated acts should be particularly pronounced for those member states, whose positions deviate the most from the Commission’s position and are thus least likely to have been accommodated in the adopted act. Conversely, in the context of implementing acts, divergent preferences are more likely to be resolved during the deliberations in the comitology system. This is in line with recent studies showing that opposition to the Commission’s proposals for implementing measures is generally weak and most cases are decided unanimously (Pasarin et al. Reference Pasarin, Dehousse and Plaza2021).

H1a: Member states are more likely to experience compliance problems, the more their preferences deviate from the Commission’s preferences, and this effect is stronger for delegated than for implementing acts.

Conversely, despite their loss of formal powers of scrutiny and amendment through comitology, in practice, member states may have retained ex post control over delegated acts. As discussed above, informal arrangements (notably, the 2011 Common Understanding on Delegated ActsFootnote 4 ) commit the Commission to keep consulting national experts in the adoption of delegated acts despite the formal removal of comitology for such acts. Moreover, member states can delay the adoption of delegated acts by slowing down this consultation procedure. Crucially, the Council retains the nuclear option of vetoing delegated acts, which may dissuade the Commission from deviating from member states’ preferences. So, if member states are effectively able to retain control over delegated acts, we should observe that:

H2: There are no differences in member states’ probabilities of not complying with delegated and implementing acts.

Moreover, if member states maintain control over all types of tertiary legislation, we also do not expect differences in the determinants of non-compliance with delegated and implementing acts:

H2a: There are no differences in the determinants of member states’ compliance with delegated and implementing acts.

However, in its 2014 Initiative to complement the Common Understanding on delegated acts as regards the consultation of experts, the Council assessed that “many of the difficulties experienced are due to insufficient guarantees about a proper consultation of experts during the preparation of delegated acts” and “the way in which the Commission consults experts at the moment is insufficient.”Footnote 5 If the Council fears less control over the content of delegated acts, it may consent to the Commission adopting delegated acts only in relation to highly technical but non-controversial issues. This would result in a selection bias, whereby implementing rather than delegated acts cover relatively more controversial issues. This assumption is in line with recent findings showing that the member states strongly favor implementing acts to delegated measures, as the former grants them more control in shaping executive law-making (Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020). Consequently, we would expect that:

H3: Member states are less likely to experience compliance problems in relation to delegated acts than to implementing acts.

In turn, a selection bias in implementing acts toward more controversial issues should result in the higher importance of preference-based explanations of member states’ non-compliance with such acts than with delegated acts:

H3a: Member states are more likely to experience compliance problems, the more their preferences deviate from the Commission’s preferences, and this effect is stronger for implementing than for delegated acts.

Based on the third assumption, ex ante selection is driven by member states’ fear that delegated acts allow the Commission to adopt rules that diverge from member states’ preferences. However, there are alternative selection mechanisms that could both affect the adoption of delegated acts and the subsequent stages of policy implementation. Research on delegation argues and finds that EU legislators grant more powers to the Commission for complex issues (Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015). Policy complexity creates information asymmetry between the ministers in the Council about the administrative and implementation conditions in different member states (Franchino Reference Franchino2007), while it is easier for the centralized bureaucracy to acquire the necessary information (Junge et al. Reference Junge, König and Luig2015). Moreover, a recent study finds that the Council and the EP are more likely to agree to delegate legislative powers to the Commission to adopt delegated acts when the secondary law deals with highly complex issues (Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020). As policy complexity increases the information asymmetry between the EU legislators, the EP is likely to demand delegated acts to decrease its information disadvantage. Consequently, like with H1, we can expect that member states are less likely to comply with delegated acts than with implementing acts. However, the mechanism is different: non-compliance is attributed to issue-level complexity and not to member states’ limited influence over delegated acts. Given the complex nature of the delegated measures, member states will need high levels of bureaucratic capacity to implement them in national law. We therefore expect:

H4a: Member states are more likely to experience compliance problems, the lower the government effectiveness, and this effect is stronger for delegated than for implementing acts.

Research design

To test our hypotheses, first, we compiled a dataset of delegated and implementing directives adopted by the European Commission between 1 December 2009 and 31 December 2016 based on the EUR-Lex database. Then, we collected information about member states’ compliance activities with these Commission directives and our explanatory variables, as detailed below.

Dependent variable measurement and modeling

EU directives need to be incorporated (i.e., transposed) into national legislation before a specified deadline by the relevant national authorities. Failure to meet the transposition deadline is construed as non-compliance with EU policy and is subject to infringement proceedings by the EU Commission.Footnote 6 We collected information about the timeliness of transposition measures member states have reported to the Commission as evidence that they have incorporated delegated and implementing directives into their national legislation – our key dependent variable. A member state delays transposition (coded as 1, otherwise 0) when national authorities fail to notify an implementing measure to the Commission before the deadline specified in a directive. To avoid exaggerating member states’ non-compliance, we only consider delays that occurred six weeks after the deadline or later.

As a robustness check, we replicated the analysis with an alternative dependent variable based on information on infringement proceedings the Commission has initiated against member states for non-compliance with any of the tertiary directives in our dataset. We recognize that transposition delays do not capture the correctness of the transposed legislation. In a similar vein, infringement data at least partially reflect the Commission ability and strategic considerations to monitor and enforce compliance with EU policies. Thus, infringement proceedings capture cases of non-compliance, on which the Commission decides to act. Many studies show that the Commission wields its enforcement powers selectively (König and Mäder Reference König and Mäder2014; Steunenberg Reference Steunenberg2010; Zhelyazkova and Schrama Reference Zhelyazkova and Schrama2023). For example, the Commission has become less willing to lodge infringement cases when these would aggravate relations with the EU member states (Kelemen and Pavone Reference Kelemen and Pavone2023; Toshkov Reference Toshkov2016). Arguably, the Commission has limited discretion to act strategically in the context of delayed transposition of EU directives, where the infringement procedure starts almost automatically (Cheruvu Reference Cheruvu2022; Zhelyazkova and Schrama Reference Zhelyazkova and Schrama2023). In our sample, all infringement cases concern delayed transposition or non-notification, which increases our confidence in the measure. Therefore, besides transposition delays, we employ infringement cases as an additional indicator of non-compliance as a robustness check.

The infringement procedure generally starts with the issue of a letter of formal notice regarding suspected violations. If a member state fails to resolve its implementation problems after the first stage, the Commission issues a reasoned opinion. Whereas reasoned opinions establish that a member state has violated EU laws, there are too few observations of reasoned opinions in our data to be able to conduct any meaningful analyss. Therefore, the analysis focuses on letters of formal notice. Nevertheless, we also present rare event models on reasoned opinions in the appendix (Models 2 and 3 of Table 4) as a robustness check.

Both dependent variables – transposition delay and the issue of formal letter by the Commission for member state non-compliance – are binary, and, therefore, we employ logistic regression models. Moreover, our observations are member state–directive dyads as each member state must comply with each directive. Consequently, we apply crossed-level logistic regression, which nests observations in both directives and member states to deal with violations of the assumption of independence of cases.

Independent variables

The main independent variable distinguishes between delegated and implementing measures (Delegated = 1, implementing = 0). It is used to test expectations about the effect of different types of tertiary measures on member states’ non-compliance (H1, H2, and H3). To test the conditional hypotheses, we measure the preference divergence between each government and the Commission (Government-Commission policy divergence) (H1a and H3a) and member states’ bureaucratic capacities (Government effectiveness) (H4a).

For Government-Commission policy divergence, we combine information from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP) (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2017) on party positions with the ParlGov database (2018) on parties in government (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2018). The CMP dataset enables us to extract policy-specific party positions regarding each policy sector based on parties’ electoral programs in each EU member state except Malta.Footnote 7 We matched the relevant manifesto items with their respective policy fields in the data on executive/tertiary measures. One of the challenges of using text data is converting counts of text items into a continuous policy dimension. In this study, we employ the commonly used scaling approach proposed by Lowe et al. (Reference Lowe, Benoit, Mikhaylov and Laver2011) to measure party positions based on the manifesto data. Subsequently, we computed the policy-specific position of each government in the Council (except Malta) as the average of the positions of government parties, weighted by their share of seats in government (Crombez and Hix Reference Crombez and Hix2015). For the Commission position, we took the policy-specific position of the party of the median Commissioner on the policy dimension of an act. Thereafter, we computed the absolute distance between each government and the Commission at the time of adoption of the respective tertiary act.

Our measure for Government effectiveness is based on the “Government Effectiveness” indicator from the World Bank Indicators database (2019). The indicator captures perceptions about the quality of public services, as well as the quality of policy formulation and implementation in various countries.

Finally, we employ interactions of the variable Delegated directive with Government-Commission policy divergence and Government effectiveness to test our conditional hypotheses H1a, H3a, and H4a.

We further control for several variables at the state and the directive levels that may confound the hypothesized relationships. At the state level, we differentiate between Central and East European (CEE) and older member states with a dummy variable. Past research has demonstrated higher compliance of newer EU member states (Börzel and Sedelmeier Reference Börzel and Sedelmeier2017; Sedelmeier Reference Sedelmeier2008; Zhelyazkova and Yordanova Reference Zhelyazkova and Yordanova2015).

We also account for member states’ size and power by incorporating information about their Voting weights in the EU Council under the QMV procedure based on the Treaty of Nice (Börzel Reference Börzel2021; Kaeding Reference Kaeding2006; Perkins and Neumayer Reference Perkins and Neumayer2007).Footnote 8 Bigger states can more easily amass the qualified majority necessary to veto and resist Commission enforcement (Jensen Reference Jensen2007). This could lead bigger member states to experience less non-compliance and fewer infringement cases than smaller member states. Country voting weights thus serve as a proxy for countries’ influence in Council decision-making, in line with the theoretical literature that underlines the predominance of compromise in the Council (Klüver and Sagarzazu Reference Klüver and Sagarzazu2013; Thomson Reference Thomson2010).

Another control variable reflects Government change between the adoption of the directive and the transposition deadline (coded as 1, otherwise 0). Even if a national government ensures that the adopted Commission measures are in line with its policy preferences, this may not be the case for the parties that take office during the implementation of the tertiary act. Furthermore, government changes could disrupt the implementation process, as they entail learning costs for ministries to complete the tasks started by the previous administration. As a result, we expect that a change in government negatively affects member states’ compliance with Commission measures.

At the directive level, we control for Legislative scope of the directive with an index using a principal component analysis of the number of recitals, number of articles, and number of words in each tertiary act. Some of the Commission acts have a more limited scope than others and, thus, may be easier to implement. Moreover, we control for the number of days between the directive adoption and its transposition deadline (Deadline length). On the one hand, member states are expected to exceed the transposition deadline if they are provided with limited time to transpose a directive. On the other hand, if tertiary directives indeed only supplement and clarify existing EU legislation, shorter deadlines could signify that member states need to make trivial changes to national policies. The analysis also includes fixed effects for each policy area in the main analysis and for member states in the robustness checks (Table 5 in the appendix).

Results

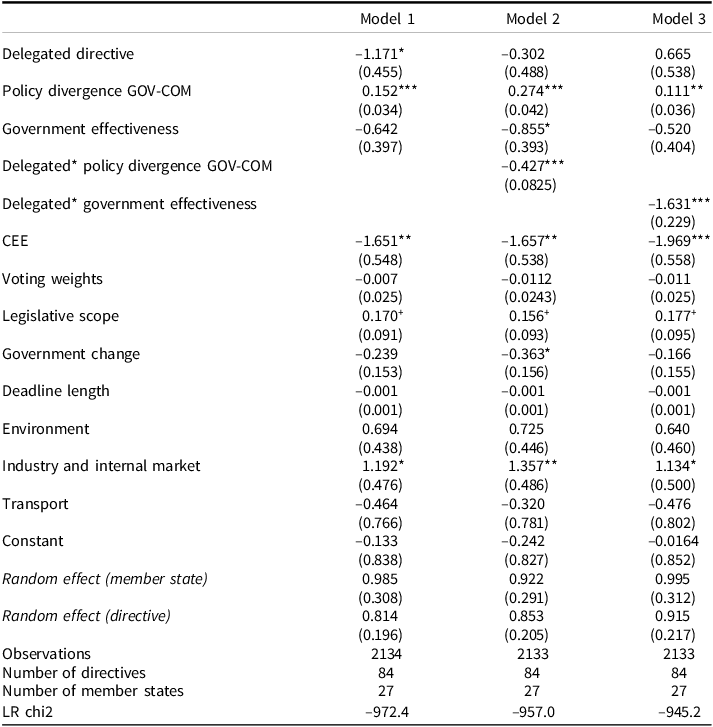

Tables 2 shows the results from the analysis of whether and, if so, under what conditions delegated directives are associated with more or less transposition delays than implementing acts, while we present our parallel analysis of infringement cases in Table 3 in the appendix. Model 1 includes the key independent variable and all controls. Models 2 and 3 also include interaction terms to test the conditional hypotheses on how the probability of non-compliance with tertiary directives is affected by member states’ willingness and capacity to comply.

Table 2. Cross-classified multilevel logistic regression of transposition delays

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses.

+ p < 0.10.

* p < 0.05.

** p < 0.01.

*** p < 0.001.

The reference policy is Agriculture.

Contrary to H1 and H2, irrespective of the dependent variable (transposition delays or infringement cases), the results show that member states are more likely to comply with delegated acts than with implementing acts. The coefficient for Delegated directive is negative and significant in both analyses of transposition delays and infringement proceedings (Model 1 in Tables 2 and 3 in the appendix). The average predicted probability of a transposition delay for delegated acts in our analysis is 0.11 or 0.16 lower than that for implementing acts. In turn, the average predicted probability of an infringement case for non-compliance with delegated acts is 0.06 or 0.16 lower than that for implementing acts. These results offer support for H3, which hypothesized less non-compliance with delegated than with implementing acts. The finding is in line with the assumption that member states are likely to restrict or block the Commission from adopting delegated acts if these concern contentious issues. Consequently, delegated acts end up covering non-controversial cases that are easier to implement than directives adopted under comitology.

A qualitative analysis supports this conclusion. The EU legislators seem to actively oppose and prevent the formal adoption of delegated acts that contain controversial issues, citing the legal requirement that delegated acts can only amend or supplement “non-essential elements” of secondary legislation (Article 290 TFEU). Soon after the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the ECJ reaffirmed that delegated acts should not include provisions that “require political choices falling within the responsibilities of the European Union legislature” (Judgment of 5 September 2012, Parliament versus Council [Frontex], C-355/10, EU:C:2012:516). Both the EP and the Council have used these arguments to block the adoption of delegated acts on controversial issues. For example, in 2019, the EP objected to a delegated act on asylum, migration, and integration fund (C201808466), which aimed to establish “controlled centers” for asylum seekers and third-country nationals not fulfilling the conditions for entry and stay. The EP argued that the concept of “controlled centers” is controversial and constitutes an “essential element.” Another example is the Council’s recent veto of a delegated act on sorting and recycling of waste on the grounds that the Commission went beyond the delegation granted in secondary law. The Council contested the obligation that the member states should provide easily accessible information to the public regarding materials collected but not recycled. Arguably, such a requirement could politicize the effectiveness of recycling systems in member states and increase the domestic costs of implementation.

Conversely, the Council strongly favors implementing acts over delegated acts, especially if these concern politically contentious issues. A prominent example is the adoption of the EU regulation 2012/528 on the use of biocidal products, which resulted in an interinstitutional battle between the EP and the Council on whether the Commission should use delegated or implementing acts in future measures supplementing the regulation (Biocides, ECJ 16 July 2015, C-427/12). The EP conceded to implementing acts to achieve agreement with the Council on the final legislative proposal, while maintaining that “political decisions are often involved in the implementation, too” (European Parliament 2012a). The example shows that the member states can pass politically contentious issues through implementing acts. The EP can object to this but is not always successful. For instance, in the case of ECJ 5 December 2012, C-355/10, on the appeal of the EP, the ECJ annulled the Implementing Decision 2010/252 on the Schengen Borders Code on the ground that it amended essential elements of basic legislation. However, in the later judgment ECJ 15 October 2014, the ECJ dismissed a similar appeal by the EP to repeal Implementing Decision 2012/733/EU as it judged it to be within the Commission’s implementing power to provide further detail on a basic act to ensure that it is implemented under uniform conditions in all member states, so long the Commission complies with the essential general aims pursued by the basic act and does not supplement or amend it. Overall, ambiguities remain as to what constitutes essential and non-essential elements of basic acts or how providing further details differs from supplementing these elements.Footnote 9

Adding to this qualitative evidence, our statistical analysis suggests that the introduction of delegated acts has not facilitated uncontrolled executive law-making or, at least, such executive drift is not reflected in member states’ level of compliance with tertiary legislation. This is despite the lack of formal scrutiny of delegated acts through comitology committees of member state policy experts and can be explained by alternative informal control through strategic selection, which we turn to next.

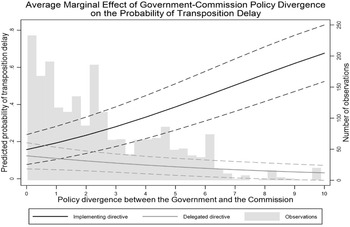

The results for the conditional hypotheses support this claim. The statistically significant interaction term of Delegated directive with Government-Commission policy divergence indicates differences in the impact of preference divergence on compliance with delegated and implementing acts. We explore these differences closer in Figure 1, which displays the marginal effects on transposition delay of delegated versus implementing acts at varying levels of divergence between government and Commission positions on policy-specific issues. As this divergence increases, on average, the probability of delayed transposition of delegated directives remains low and even becomes indistinguishable from zero. The opposite holds for implementing acts, which are associated with a statistically significant increase in the probability of delayed transposition as the policy positions of a government and the Commission grow. The probability of a transposition delay for implementing acts increases from 0.16 to 0.68 as the divergence in the policy preferences of the Commission and a member state government grows from its minimum to its maximum level observed in the dataset.

Figure 1. Predicted probability of delayed transposition of delegated and implementing directives over levels of policy divergence between a government and the Commission.

The additional robustness analysis of infringement cases shows that Government-Commission policy divergence has a negative effect on the initiation of infringement proceedings against non-compliance with Commission directives (Model 1 of Table 3 in the appendix). This result can be explained with the strategic considerations of the Commission, which may be reluctant to punish member states for violating tertiary measures, especially when it does not expect them to comply even after the infringement procedure. However, further exploration of the conditional effects (in Model 2 of Table 3 in the appendix) reveals that this holds for delegated acts. Provided that delegated directives should only concern specifications of non-controversial issues (in line with H3), starting infringement proceedings could be challenged by member states on the premises that the Commission has gone beyond its delegated competencies. In turn, the Commission may refrain from pursuing non-compliance with delegated acts in the face of policy disagreement with the violating government.

In sum, the results contradict H1a. Both transposition delays and infringement cases with delegated acts cannot be attributed to ideological conflicts between a government and the Commission. This suggests that delegated acts have not deprived member states of the ability to assert their preferences at the policymaking stage, which should have been reflected in their subsequent opposition to such acts “through the backdoor” at the implementation stage. The results also contradict H2a, as both capacity-based factors and (in the analysis of transposition delays) preference-based factors have different effects on member states’ compliance with delegated and implementing executive acts. Instead, the results support H3a, as preference divergence is more relevant for the timely transposition of implementing than delegated acts. These findings, together with the qualitative evidence, indicate a relatively more controversial nature of implementing directives.

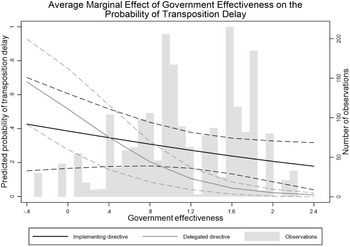

Finally, in line with H4a, we find support that delegated acts require more government capacities during implementation. The probability of non-compliance with delegated acts significantly decreases with higher levels of government effectiveness, as the significant negative interaction term in Model 3 of Table 2. The same holds in the analysis of the alternative indictator of non-compliance (see Table 3 in the Appendix). Figure 2 illustrates these results for transposition delays. The probability of a transposition delay for delegated acts decreases from 0.68 to just 0.01 as government effectiveness increases from its minimum to its maximum level. Put differently, non-compliance with delegated acts is attributed to capacity limitations in the EU member states rather than the loss of influence in the adoption of these directives. While delegated acts include non-political issues, they are also characterized by higher levels of complexity and thus require bureaucratic expertise. This finding is in line with the literature on delegation to the Commission, which shows that EU legislators agree to delegated acts for technically complex policy issues (Yordanova and Zhelyazkova Reference Yordanova and Zhelyazkova2020).

Figure 2. Predicted probability of delayed transposition of delegated and implementing directives over the level of governmental effectiveness.

Further robustness checks

To better understand the negative effect of delegated acts on non-compliance, we considered further the substantive differences between delegated and implementing acts. Recent research suggests that EU acts with long titles containing many numbers “signal that the content of these measures is uncontroversial” and of low salience (Blom-Hansen and Finke Reference Blom-Hansen and Finke2020, p. 162). Based on our dataset, delegated acts have significantly longer titles and include more numbers than implementing measures. Whereas implementing measures contain on average 24 words in a title, delegated acts have double this amount (48 words in a title). More importantly, the differences in compliance are no longer significant once we include the number of words in a title in the analysis. These results are presented in the appendix (Models 1 and 3 of Table 4). They indicate that the significant effect of delegated acts is captured by the level of controversy of the covered issue, supporting the argument that the member states only agree to the adoption of delegated acts for non-controversial issues. A closer look at the topics addressed by different types of executive measures further supports the conjecture that delegated acts address less salient and non-controversial issues, such as adapting to technical progress. Instead, more politically salient topics are addressed through implementing acts.Footnote 10

Discussion and conclusion

The goal of this study was to investigate the effectiveness of different kinds of legislative control mechanisms over the EU executive and their implications for policy compliance. For this purpose, we studied the consequences of the introduction of the new EU system of delegation of quasi-legislative powers to the Commission to unilaterally adopt executive measures (i.e., delegated acts). This institutional change de facto provided EU legislators with a choice between different formal tools to control the Commission’s tertiary acts: amendment and approval right through a comitology system for implementing acts or only ex post veto control for delegated acts. We argued that this choice affects the subsequent member states’ level of compliance with different types of executive measures. To examine this, we analyzed member states’ compliance with the new delegated acts as compared with the established implementing acts. Moreover, we studied if the determinants of non-compliance with these two types of acts differ to extrapolate member states’ de facto control over the use and content of delegated acts.

Based on the analysis, we found that delegated acts are associated with fewer compliance problems than implementing acts. More precisely, delegated acts incur fewer transposition delays and infringement cases. Thus, member states do not seem to oppose delegated acts by failing to comply with them at the implementation stage. These results do not support the conjecture that delegated acts have led to a loss of control for member states over the Commission relative to the established comitology system. The most likely explanation based on our argument and findings is that member states strategically select relatively less politically controversial issues for policymaking via delegated acts, that is, cases which would not be contested. Consistent with this interpretation, first, the quantitative analysis shows that preference divergence between the Commission and the member states significantly shapes compliance with implementing acts, while it does not affect compliance with delegated acts. Instead, non-compliance with delegated acts is attributable to limited bureaucratic capacities of EU governments to comply with the relatively more complex delegated Commission directives. Second, qualitative evidence suggests that both the Council and the EP are likely to block the Commission proposals for adopting delegated acts, when at least one of the institutions considers the proposed measures as contentious and politically salient. In sum, we find that capacity-based factors explain non-compliance with delegated acts, while preference-based factors are more relevant for compliance with implementing acts.

The idea that the new highly politicized executive measures cover mostly non-controversial issues alleviates concerns about diminished member states’ influence over executive policymaking. More generally, our results indicate that legislators can successfully prevent undesired policy drift and, consequently, non-compliance, through strategic ex ante selection of control mechanisms. However, these results then also suggest that the legislators avoid entrusting the EU executive with any potentially significant powers to adopt delegated acts. This echoes Bergström's (Reference Bergström2005: 358) that about the impact of the abolition of comitology in the context of delegated acts would deprive member states of key means of influence and continuous control. Consequently, member states have incentives to avoid delegated acts when the consider that the stakes are high.

At the same time, we should acknowledge some limitations of the study. Our findings are based on transposition delays and infringement cases. Arguably, transposition delays do not capture the substantive conformity of government measures, and infringement proceedings depend on the Commission strategic considerations to prosecute law-violating member states (Kelemen and Pavone Reference Kelemen and Pavone2023; König and Mäder Reference König and Mäder2014; Zhelyazkova and Schrama Reference Zhelyazkova and Schrama2023). Non-compliance with executive measures implies that the Commission has failed to specify and clarify member states’ obligations in a way that facilitates compliance. Consequently, the Commission may be reluctant to start infringement proceedings against non-conformity. Unfortunately, there is no data that systematically measures conformity with the content of executive measures. On the flip side, the analyses of both transposition delays and infringement cases show that delegated measures experience less compliance problems, which boosts our confidence in the results. Moreover, it is possible that member states’ loss of influence is not reflected in their compliance with EU law. Recent research more directly analyzes the level of dissent between the Commission and member states’ representatives in comitology committees (Finke and Blom-Hansen Reference Finke and Blom-Hansen2022; Pasarin et al. Reference Pasarin, Dehousse and Plaza2021). Future research should analyze further the extent to which the Commission incorporates the preferences of different member states in the adoption of executive measures.

Nevertheless, this study is a first step toward better understanding the impact of different types of Commission measures on the EU member states. To our knowledge, past research has not compared the drivers for member states’ compliance with different types of EU executive measures. The analysis of compliance with executive measures is often ignored based on the premises that Commission directives are too technical and easier to implement. However, this assumption is at odds with ideas about the expanding powers of the Commission to unilaterally legislate on issues that are of high importance to the member states (Williams and Bevan Reference Williams and Bevan2019). Indeed, our analysis showed that some executive measures are politically salient and could incur compliance problems within the member states. In particular, member states are more likely to delay the transposition of implementing acts, especially when the Commission and a EU government have divergent policy-specific positions. In other words, the Commission manages to sneak in controversial issues in executive measures with which member states disagree and that lead to higher non-compliance at the implementation stage. Future research should shed more light on the consequences of increased bureaucratization of EU legislation on the member state governments and national policies.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X24000096

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/DOORVS, Harvard Dataverse, V1.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Max Haag for the research assistance with the data collection, the participants at the 2019 EUSA Conference in Denver and the members of the European and Global Governance Group at Erasmus University Rotterdam (Markus Haverland, Michal Onderco, Geske Dijkstra, and Pieter Tuytens) for their feedback on earlier versions of the study, as well as editor and the three JPP referees for their constructive comments and suggestions for improvement.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.