Two months ago, you submitted a paper to the American Political Science Review, the political science discipline’s flagship journal. Ever since, you’ve anxiously awaited a decision. Today, you receive an email from the editors, and … it’s an invitation to revise and resubmit! At first you are elated, but as you read the decision letter, in which the editors outline the revisions they see as necessary and important, you realize you have a lot of work left to do.

Then you notice something unusual: the letter bears a collective signature (Sincerely, The Editors, American Political Science Review). “What kind of process produced this decision?” you wonder. How did the editors decide to invite you to revise and resubmit? How did they select which aspects of the reviews to emphasize? And, if an editorial collective will be evaluating your revision, then how can you best navigate the next steps? Maybe the uncertainty surrounding these questions makes you feel uncomfortable. Maybe, to borrow the language of the feminist thinker and advocate Sara Ahmed (Reference Ahmed2017), it makes you “sweaty.”

Our team’s collaborative decision-making model intentionally unsettles dominant norms and practices in political science and in academic journal editing more generally. In this “Notes from the Editor,” we seek to ease any discomfort it may induce by explaining the principles and the rationale for our model. We begin by comparing the traditional, hierarchical journal management model with the collaborative model that we have adopted, before considering the challenges and the advantages of our approach.

The “Person-in-Charge” Model

Traditionally, scholarly journals have been run by a single (typically white, male) scholar: a person who historically was identified as the “Managing Editor” and today is usually called the “Lead Editor” or “Editor-in-Chief.” This individual functions as a final decision maker: the arbiter of what is considered publication-worthy research. Those selected as lead editors tend to be established scholars with extensive, mainstream publication records, a profile that solidifies their legitimacy as gatekeepers.

For example, when the APSR was first published in 1906, the Managing Editor was Westel Woodbury Willoughby, a professor at Johns Hopkins, who was one of the founders of the nascent American Political Science Association and who would go on to serve as the Association’s president. For its first century, the APSR was run by a series of Managing Editors with profiles comparable to Willoughby’s. Except for two four-year periods, when that role was occupied by white women (Dina Zinnes, 1982–1986 and Ada Finifter, 1996–2002), those editors were white men. And even when Zinnes and Finifter took the reins, the journal retained its “person-in-charge” model.

Under the traditional model, the Managing or Lead Editor signs the journal’s decision letters, and authors ostensibly can rest assured that the signatory made the decision and will be responsible for all subsequent decisions about the manuscript. However, the demands of running modern journals are such that the person-in-charge model may mask what happens behind the scenes. Especially in the past several decades—as the volume of journal submissions has grown for major journals and many disciplines, including political science, have become at once increasingly specialized and increasingly diverse—most Lead Editors have taken to working with a team of other scholars, who are typically called “Associate Editors.” Associate Editors take primary responsibility for manuscripts that fall within their areas of expertise. On some editorial teams, Associate Editors sign their own decision letters, whereas on others, Associate Editors draft them and then Lead Editors review and sign them.

The Collaborative Model

When the UCLA team took over the APSR in 2008, they explained in their first “Notes from the Editor” that they were “pioneering a new model of editing, using a team of scholars with different areas of expertise who would deliberate together on manuscripts as they progressed through the review process.” The UCLA team did have a “person in charge.” They even returned to the original title for that role, calling him the “Managing Editor.” However, they referred to themselves as an editorial collective, and they emphasized that they held weekly meetings, during which they consulted with one another and deliberated about manuscript decisions.

We are the fourth team to edit the APSR, and the team model is now well established across the discipline. Editorial decision making in political science today is considerably less centralized and top down than it was through much of the twentieth century. That said, most journals are still run by a Lead Editor, who directs and coordinates the work of a team of Associate Editors, who in turn solicit reviews and make or recommend decisions on manuscripts in their fields of expertise.

Our team structure draws more explicitly on and extends the collaborative model. In addition, we intentionally introduce feminist values and principles to our editorial process. By leveraging the experiences and perspectives of our substantively and methodologically pluralistic and racially and ethnically diverse team of coequal editors, we intend to fully disrupt the gate-keeping function of the “person in change.” We practice reflexivity about our positionality, as well as about the assumptions that we bring to the table, as scholars with particular substantive interests, methodological skills, and epistemological commitments. We have self-consciously modeled ourselves as a nonhierarchical collaborative, in the tradition of women-centered NGOs (Timoshkina Reference Timoshkina2008), transnational academic organizations (Bickham Mendez and Wolf Reference Bickham Mendez and Wolf2001), and feminist business enterprises (D’Enbeau and Buzzanell Reference D’Enbeau and Buzzanell2013). Our collective signature reflects this nonhierarchical structure.

Concretely, at all times two of our team members serve as Co-Lead Editors, who oversee the smooth running of the journal and ensure that no manuscripts fall through the cracks. Team members cycle through this position, with most of us serving one 12-month term, the first six months of which overlap with the term of one team member and second six months of which overlap with the term of another. In other words, one Co-Lead changes every six months. These overlapping terms ensure continuity, while also regularly bringing fresh energy and ideas to the lead position.

Co-Leads, however, are not “Co-Persons in Charge.” Although Co-Leads coordinate the journal’s day-to-day business, on our team, every editor is an equal member. No one person defines the journal’s direction.

Our team members all participate in weekly meetings, during which we discuss manuscripts and other journal business. We listen to and engage one another’s views about important decisions (such as how to constitute our Editorial Board or whether to adopt a particular editorial policy), and, if possible, we try to arrive at consensus on such decisions. We also collaborate on many day-to-day decisions, such as whether to desk reject a particular manuscript rather than send it for review. In the case of desk rejects, our policy requires that at least two editors agree before we desk reject a manuscript. If an editor proposes to desk reject a manuscript but another team member disagrees, then the editor who supports sending the manuscript for review takes primary responsibility for shepherding that manuscript through the review process.

More generally, we collaborate through all steps in the editorial process, drawing on the team’s collective expertise, especially in the cases of papers that do not fit squarely within just one editor’s areas of strength. We regularly ask one another for suggestions for reviewers, seek guidance on how an author might successfully reconcile reviewers’ concerns, and request feedback from each other on the novelty of a manuscript’s contributions.

We also work together, often in smaller configurations, to plan the journal’s issues, to expand authors’ and reviewers’ commitments to research ethics, to promote contributors’ research through blogs and social media posts, and more generally to maintain and improve the journal’s quality and integrity, while broadening its readership, relevance, and contributor pool.

Challenges of the Collaborative Model

We have worked hard to forge our shared approach and vision, and in the process, we have found that working collaboratively takes time, commitment, and effort. We don’t always agree; to the contrary we often disagree, respectfully challenging one another’s assumptions, judgments, and points of view. While navigating disagreements can be challenging, we believe that these engagements ultimately lead to better decisions.

It is our considered conviction that the benefits of our collaborative model outweigh the costs. Nevertheless, we realize that it raises some valid concerns. One important concern is that nonhierarchical, collective decision making can be time consuming and inefficient (Ferree and Martin Reference Ferree, Martin, Ferree and Martin1995; Bickham Mendez and Wolf Reference Bickham Mendez and Wolf2001). Because we share this concern, we closely monitor our average time-to-decision (TTD), the measure of efficiency mostly commonly employed by scholarly journals.

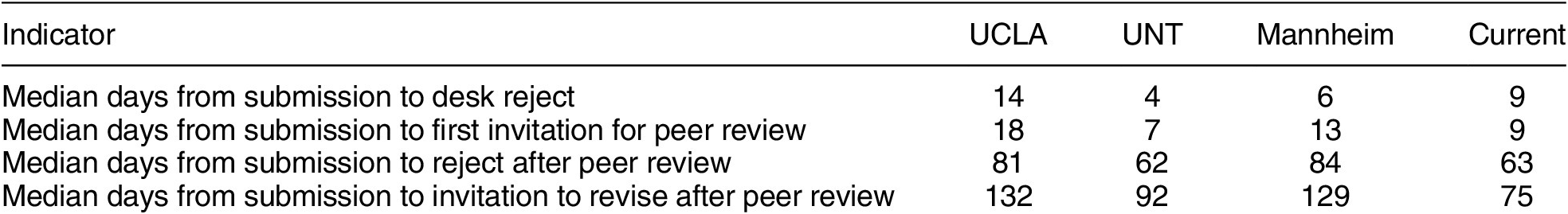

As Yang’s (Reference Yang2010) work suggests, collaborative decisions tend to take longer than decisions that are associated with hierarchical editorial models. Although it is difficult to measure our turnaround times for all manuscripts with a final disposition (because many of the manuscripts that have been initially submitted since we first began our tenure have not yet completed the entire review process), we can compare turnaround times between new submissions and either first invitations to review or desk reject decisions.

The results are mixed. With respect to desk reject decisions, our TTD average is longer than that of the previous (Mannheim-based) team and it is more than double that of the UNT team (See Table 1). However, our median time from submission to first invitation for peer review remains comparatively short, which suggests that our policy of requiring at least two editors to concur on desk rejects causes the longer TTD for those decisions.

Table 1. Workflow/Turnaround Times, 2008–2021

A second set of challenges centers on transparency and accountability. “If there is no ‘person in charge,’” one might reasonably worry, “then how will people know who made which decisions, and why, and how, they made them?” Journal editors who work collectively and collaboratively (one might think) will be insufficiently accountable to authors, reviewers, readers, members of their scholarly disciplines, and other stakeholders. If authors or reviewers have questions about how manuscripts were handled, if readers have issues with published articles, or if someone simply needs to plead for an extended deadline, being able to direct those concerns to an identifiable individual who has authoritative standing can be reassuring.

We appreciate the appeal of individualized accountability. Our Co-Lead Editors are involved in day-to-day journal communications, and they respond promptly to routine queries. In addition, they coordinate our team’s response to larger concerns, which often involve individual editors with particular roles (such as Ethics Editor or Appeals Editor) taking the lead. At the same time, we practice accountability and transparency as a team. For example, we regularly share information about our editorial processes and workflow, as well as various data including data on the composition of our reviewer pool and our submitting and published authors.

A third set of challenges stems from the discomfort (the “sweatiness”) that this nontraditional editorial model may induce. It is not uncommon, especially in male-dominated and masculine contexts (for example, the military, the Catholic Church, or trading firms) to see backlash when women in organizational leadership positions introduce egalitarian, democratic, and collaborative decision-making practices (see Eagly and Carli Reference Eagly and Carli2003). Arguably, political science remains a male-dominated, masculine discipline, the members of which have become accustomed to a “person-in-charge” (typically, one whose own research is rooted in quantitative methods or formal modeling).

If so, then discomfort and backlash are to be expected. However, as Eagly and Carli (Reference Eagly and Carli2003) suggest, backlash may abate as institutional practices and cultures change. So as feminist models of journal editorship become more common, their distinctive leadership approaches may become valued for the advantages they bring.

Advantages of a Collaborative Model

Our large, diverse, and collaborative team leverages multiple voices, forms of knowledge, and perspectives. We intentionally flatten the editorial hierarchy, incorporating rotating responsibilities and shared decision making and accountability. We hope that these features of our editorial model will not only improve the quality of our editorial decision making but also help to flatten some of the discipline’s hierarchies.

As noted above, we regularly rotate the Co-Lead Editor role. We also rotate responsibility for performing many of the journal’s other important functions, from promoting equity, inclusion, and ethical research practices to managing publicity and outreach, as well as addressing and improving transparency and accountability. As individual members of our team shift positions within this structure, they bring their distinctive scholarly and personal perspectives to the table, lending their insights to a new set of collective questions and deliberations. “What are the barriers that prevent some groups of scholars from submitting to the APSR?” is an example of a question that one of our team members recently posed to the group, generating a discussion of concrete steps we will take to generate a deeper understanding of those barriers and identify ways to mitigate them. Another example of a question a team member recently articulated is “How can we create an online scholarly community?” A third is “How can we use our platform to increase accessibility by articulating expectations and norms (the “hidden curriculum” of publishing)?”

We believe that bringing plural perspectives to these and related problems will help to diversify political science by broadening the research topics and approaches and the range of voices that appear in the pages of the APSR. At the same time, as we cultivate relationships, not only among the 12 editors on our team but also with the members of our Editorial Board and our Editorial Assistants and Managing Editor, we hope to strengthen the feminist intellectual network in our discipline (forged by, among others, Journeys in World Politics, Visions in Methodology, and the WPSA Feminist Theory Group).

Conclusion

That “we” voice that you read in your revise-and-resubmit letter indicates genuinely team-based deliberation and decision making. Similarly, the collective voice that you read in this (and our other) “Notes from the Editors” reflects a composition process that incorporates multiple authorial voices. Our signature line (“The Editors”) means exactly what it says; the members of this editorial collective share in the work that we do. This sharing underpins our collective, feminist model.

Moving into our second year of editorship, we will continue thinking of our editorial work as a feminist enterprise. As Martin (Reference Martin, Fenstermaker and Stewart2020) recommends, we will attend to and listen to our stakeholders, and we will remain reflexive about the gendered, racialized, and other power dynamics embedded in our practices and outcomes. We will also continue our outreach work and our efforts to augment transparency about our stewardship of the journal. Our goal is to continue to refine and improve our feminist model, which we believe is an attractive one that others might consider adopting and adapting.

Sincerely,

The Editors,

American Political Science Review

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.