In October 1814, when she was twenty-two, Anne Lister wrote ‘clytoris’ on a scrap of paper.1 But she did not find the clitoris ‘distinctly for the first time’ until 1831, when she was forty.2 Why did it take so long? She had clearly been experiencing pleasure through the clitoris and giving pleasure to other women. She attended lectures in Paris on anatomy and read many medical texts. Yet until 1831, when she tried to find the clitoris on her own and her lovers’ bodies, she seems to have confused the cervix with the clitoris.

Where could she find information about the clitoris and how did she interpret it? Famously, anatomist Renaldo Columbus claimed to discover the clitoris in 1559, and declared it was the seat of women’s pleasure. Furthermore, popular anatomy books asserted that women could not conceive without an orgasm, so as the source of women’s pleasure, the clitoris was rather important. At the same time, popular anatomists traditionally regarded the vagina as analogous to the penis, which made things somewhat confusing. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, historian Thomas Laqueur argues, scientists began to understand that female orgasm was not necessary for conception; thus, the clitoris became less important, and some medical texts began to leave it out.3 Other historians have criticised this chronology as too simple. Recently, Alison M. Moore has argued that in fact nineteenth-century medical texts did include the clitoris.4 However, aside from Laqueur, these recent articles skip from the seventeenth and early eighteenth century to the 1840s, leaving out the early nineteenth century, Anne’s time. By looking at Anne’s reading about the clitoris, we can illuminate the debate about what nineteenth-century people could know about the clitoris and when they knew it.

Anne’s diaries reveal that it was not enough for a medical or popular book simply to mention the clitoris. Anatomy could be difficult to understand: even medical experts could find it hard to understand the anatomist Vesalius’s text and images.5 Studies focus on what medical experts wrote and thought, not how women themselves interpreted them. If such an erudite and sexually experienced woman had such difficulty accurately finding it on her own body, other women would face even greater confusion. Lister’s diaries provide a rare opportunity to examine a woman’s detailed exploration of her own body and of anatomy texts, therefore contributing to the historiography about how people understood their own bodies and interacted with popular and official medical knowledge.6 A few historians have shown that eighteenth- and nineteenth-century people read popular medical tracts and learned about folk medicine, and the literate middle class also had access to books about anatomy and even venereal disease in circulating libraries.7 With Anne’s diaries, we can trace how she understood anatomy in detail. Conveniently, Anne noted each book and article she read, so that we can track where she found certain words and concepts.8

Because these texts often buried the clitoris in confusing and abstruse detail, Anne practised ‘queer reading’ to interpret them. In other writings, I use this term to explain how she found obscure references to sex between women, researched them down the rabbit hole of commentaries and used them for her own ends.9 She also had to ignore negative depictions of women who had sex with each other. I have previously written about how she read deeply in Latin classical works that scornfully depicted women who had sex with each other as ‘tribades’. Similarly, she loved the Romantic poet Byron, famed as ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’, and emulated his libertine persona to create a sense of self as a romantic hero, even though she denounced him as improper to her acquaintances.10 In this chapter, I will argue that she read anatomy books in a similarly queer way, disregarding condemnations and warnings to find sexual information fascinating and arousing.

For instance, Anne also ‘queerly’ read Onania, Samuel Tissot’s anti-masturbation tract.11 Lister had decried her own masturbatory practice (indicated as a cross in the margin of her diary) as ‘self-pollution’, as ‘shameful’ and a ‘vile habit’. Yet she never stopped masturbating, and after 1825, she no longer expressed guilt about it.12 Like many such tracts, Onania titillated in condemning by conveying information about sex, even sex between women. Although Anne only lists reading up to page 102 in Onania, further in the book the author reprints a letter supposedly from another woman who recounts how she learned pleasure with other girls in boarding schools. The book also mentions anatomist Regnier de Graaf’s theories that some women have enlarged clitorises that they use with other women.13

Two years later, Anne discussed the ‘sin of Onan’ with Mrs Barlow, her sexually experienced lover in Paris. Anne generally kept her queer reading interpretations very private: in conversations with others, she did not directly discuss sex; instead, she hinted obliquely until the other woman had implicated herself with her own knowledge. To get the sexually experienced widow Mrs Barlow to admit first to her own knowledge of female desire, Anne then ‘made her believe how innocent I was all things considered’, until Mrs Barlow implicated herself by saying she thought there was ‘little harm’ in such things. Mrs Barlow then showed Anne a French book, Voyage à Plombières, which contains a brief and oblique condemnation of lesbian eroticism. Then, she was able to discuss with Mrs Barlow that the sin of Onan – spilling his seed or semen on the ground to avoid conceiving a child with his brother’s widow – was how French husbands themselves avoided conceiving. Onania also mentioned the biblical condemnation in Romans 1:26–27 (KJV) that ‘even their women changed the natural use into that which is against nature’, implying this meant sex with each other. She and Mrs Barlow creatively decided that this meant women having sex with men contrary to nature (anal sex), and that the passage did not apply to women having sex with each other.14

Anne developed a secret language and code to record her sexual encounters both solitary and social. While she shared her code with a very few lovers, her sexual symbols seem to have been secret. Transcribers Steph Galloway and Livia Labate have also identified Anne’s sexual vocabulary and the symbols for her sexual practices she noted in the margins of her daily entries (which Anne sometimes defined in her journals).15 During her teenage relationship with Eliza Raine, Anne noted ‘felix’ (Latin for happy) in her diaries, apparently when they had sexual encounters – and also when she masturbated, for she noted ‘felix’ in her journal when Eliza was not there.16 In her diaries, she wrote when she gave or received a ‘kiss’, using the word in 1816 if not earlier.17 While she uses the word, as we would, simply to mean a kiss, it is very clear that this also meant a genital sexual encounter, perhaps deriving from the French baiser, which could mean kiss or sexual intercourse.18 But it might also mean an orgasm: for instance, in 1817 she wrote ‘[Mariana] had a very good kiss last night mine was not quite so good but I had a very nice one this morning’.19 Her lovers also gave her a kiss when they ‘got close’ or pressed together. She also used the more technical term vagina in the medical context.20

Anne seems to have worked on developing this sexual vocabulary even more intensively between 1818 and 1820, when she became embroiled with several lovers around the same time (sometimes on the same day). It is possible that some of these words were shared, and then these young women were aware amongst each other about the possibility of mutual sexual pleasure. For instance, Eliza Belcombe, Mariana Belcombe’s sister, claimed she saw Anne lick Mariana’s neck and that another girl grabbed her in bed at night, and alluded knowingly to ‘using the fingers’. But Anne disapproved of this open conversation.21 Instead, she seems to have preferred to invent or modify her own terms. She used ‘queer’ or ‘quere’ as her term for the female genitals, perhaps derived from ‘quim’, a slang term for them. She first used this term when she initiated sex with Miss Vallance in October 1818.22 In her diaries, she described how she ‘grubbled’ women, reaching up under their petticoats and stroking and penetrating them with her fingers (she specified which finger she used); to grubble is defined in Johnson’s dictionary as ‘to feel in the dark, as in Dryden’, and was used in Dryden’s translation of Ovid’s Art of Love, as ‘to grubble, or at least to kiss’. It also meant ‘grope’ in earlier times, and perhaps later in northern parts such as Scotland.23 Anne Lister first used this term on 19 October 1820, at a time when she was engaged in fervid sexual exploration with several women, and also when she had begun reading in the classics, such as Juvenal, to find obscure Latin references to sex between women.24

Anne’s particular spelling of ‘clytoris’ also provided a clue that she found anatomical information in Aristotle’s Masterpiece. This particular spelling of clitoris was found most often in some editions of the work, and in 1817, 1819, 1820 and 1821, her journal mentions reading it.25 Aristotle’s Masterpiece, a popular sex guide printed on cheap paper and sold by pedlars in several versions, was not an academic treatise but a compendium of many sources that often contradicted each other, as Mary Fissell has found.26 It is impossible to note exactly which edition of many it was that Anne read, but I have cited a 1717 version of Aristotle’s Masterpiece that contains this spelling of ‘clytoris’ and mentions other points cited by Anne. Like Onania and other popular medical and erotic literature, it intentionally had to be read against the grain: for instance, the introduction links ‘the mutual delight [men and women] take in the act of Copulation’ to the wonders of generation, and apologises that this information might ‘stir up their Bestial Appetites, yet such may know, this was never intended for them’, but only to help married couples procreate. Of course, not only married couples read it: Anne obtained her copy from her aunt, who had seized it from a maid.

Aristotle’s Masterpiece did not have illustrations depicting the location of the clitoris, and it described female anatomy in three rather confusing instances. First, just after a paragraph on the nymphaea, or labia, the ‘clytoris’ is described as the ‘seat of venereal pleasure’, and as ‘like a yard [in] Situation, Substance, Composition and Erection, growing sometimes out of the Body two Inches, but that never happens unless thro’ extream Lust, or extraordinary Accidents’. In another chapter, it compares the clitoris to the penis, claiming its ‘outer end’ is like the penis or glans in men. In the third instance, the work describes the ‘neck’ of the womb, and goes on to say, ‘near unto the Neck there is a prominent Pinnacle, which is called of Montanus, the Door of the Womb, because it preserveth the Matrix from Cold and Dust. Of the Grecians it is called Clytoris, of the Latins Proputium Muliebre [penis muliebre], because the Jewish Women did abuse this Part of their own mutual Lusts, as St Paul speaks Rom. 1:26.’ The Masterpiece also referred to the theory that women’s genitals were like men’s but turned inside out, so that by extension, the penis resembled the vagina. Of course, this is very confusing if the clitoris is also analogous to the penis, but this may explain why Anne thought that the clitoris was located in the vagina.27 Aristotle’s Masterpiece does not define the cervix, so it is possible that Anne thought that this fleshy knob in the vagina was the clitoris, or the door of the womb.

It may be that the overall frame of thinking about sex during her time, as well as in the Latin authors she read, was still so phallic and focused on penetration that it shaped her assumptions about sex. Anne came of age during the Regency period, when prudishness competed with public sexual jokes, and the upper-middle class and gentry people with whom she socialised often told erotic jokes. Anne herself often disapproved of such public ‘indecency’ of men and even the ‘gross language’ of female friends, but she also regaled female lovers with wild sexual tales. Although Mr Empson kept ‘indecent’ books in his drawer, his wife did not understand the joke Anne told her about the Wexford oyster as ‘rough without, moist within, and hard to enter’. This was a joke from Yorick’s Jests, a collection of mildly smutty and highly phallic bon mots.28

In her diaries, we can see how Anne did not clearly understand the location of the clitoris. In 1820, she mentions the clitoris – spelled ‘clytoris’ – to her lover Miss Vallance. Miss Vallance recounted that a doctor told her that ‘something came too low down and blocked the passage’, and she feared she should not marry as ‘she could not bear much and could never make anyone happy’. In response, Anne told her ‘the clytoris had slipped down too low from illness anxiety etc’.29 This resembles the discussion in Aristotle’s Masterpiece of the ‘dropping of the mother’, or when the cervix and uterus sag into the vagina, what is now called a prolapsed uterus.30 Anne seems to have been confusing the clitoris with the cervix. She also noted in her code that she was able to feel Miss Vallance’s ‘stones of ovaria’ with her fingers.31

Anne continued these explorations with Mrs Barlow in Paris. She penetrated Mrs Barlow and reported that this enabled her to feel ‘her clitoris all the way up just like an internal penis’. But Anne herself did not like anything ‘inside her’; although she tried to find her own internal clitoris, she said it hurt and did not give pleasure, and with other women, it made her feel too much like a woman.32 Instead, she decided to ‘incur’ a cross in her ‘old way by rubbing the top of the queer’ – no doubt the clitoris.33 In 1821, she tried penetrating herself with a finger after managing to use a uterine syringe, but mentioned, ‘anything of this sort would never give me pleasure or a kiss the latter is produced on the surface’.34

Aristotle’s Masterpiece and Anne’s studies in anatomy can also illuminate the wider debate about Anne’s masculinity and whether she should be seen as a potentially trans subject. As Laqueur writes, popular anatomy often depicted the vagina as like a penis turned inside out, by implication comparable in substance and function, and possibly able to turn outside in. While texts sometimes told stories of boys who turned into girls or vice versa, this does not mean that early modern people saw gender as easily fluid or reversible.35 For instance, Aristotle’s Masterpiece presented a debate between ancient Greek physicians about this. Galen is quoted as saying that a man

is different from a woman in nothing else, but having his genital members without his body, whereas å woman has them within. And this is certain, that if nature, having formed a male, should convert him into a female, she hath no other task to perform, but to turn his genital members inward, and so to turn a woman into a man by the contrary operation.36

The Masterpiece states, however, that Galen’s model refers to possible gender confusion in the womb, when an imbalance of humours might make a boy become effeminate and shrill, or a girl too strong and masculine, rather than to allow a total transformation. Yet the text quotes Severus Plineus as regarding men’s and women’s genitals as utterly different, and states that apparent transformations of girls into boys and vice versa were merely cases of mistaken identity, of boys with very small penises who were mistaken for females or females with ‘overfar extension of the Clytoris’.37

Unfazed, Anne took from Aristotle’s Masterpiece the possibility that the clitoris could grow larger. She discussed with Mrs Barlow whether her attraction to women was based on her own anatomy. She declared that this attraction was ‘all nature’: ‘I had thought much, studied anatomy, etc. Could not find it out. Could not understand myself. It was all the effect of the mind. No exterior formation accounted for it.’ Evoking Aristotle’s Masterpiece quoted above on women’s genitals as like men’s turned inside out, she ‘alluded to there being an internal correspondence or likeness of some of the male or female organs of generation’. Mrs Barlow even tried ‘To examine if I [Anne] was made quite like her but she merely observed that Anne had smaller breasts and narrow hips’. Anne also noted that rumours had spread that her physician thought there was a ‘small difference between my form and that of women in general’. She made a parallel between men with undescended testicles and the possibility that she had something internal, alluding ‘to the stones not slipping thro’ the ring till after birth, etc’.38 This most closely resembles the discussion of the development of the foetus in Blumenbach’s 1817 work on anatomy;39 Lister later visited him in Germany. But she may have also learned it from Guillaume Dupuytren, a famed French physician whom she visited for treatment for her presumed venereal disease, who explained to her that men with only one testicle had the other one undescended in the abdomen. She had been asking questions about Charles Lawton, husband of her lover Mariana.

Instead of becoming a man, Anne hoped that she could enlarge her clitoris and therefore ‘copulate with women’. In 1825 she mused to Mrs Barlow: ‘I felt as if something might come farther out and that perhaps if I had an operation performed I might have a little thing – half an inch would be convenient. It would enable me to have my drawers made differently – that is to make water more conveniently.’ She allowed Mrs Barlow to imagine that her doctor, Mr Simmons, had said this was possible.40 A few months later, she wrote in her diary that she ‘began putting up my left middle finger to bring down the clitoris, wishing it come so as to be able to copulate with women’.41 Around the same time, she worried that ‘I cannot do enough for Mrs B[arlow]. I cannot give her pleasure in any way but with my finger, and this does not suit. If I had a penis an inch or two long, or the clitoris down far enough I could manage.’ Mrs Barlow never expressed any discontent about this, and in fact said that she had more pleasure with Anne than with men.42

More reputable sources than Aristotle’s Masterpiece did not prevent Anne from confusing the cervix and the clitoris. In 1821 she read Cheselden’s Anatomy on the genital parts of men and women; it described the clitoris as the ‘chief seat of pleasure’ for women in coition, as the glans is in men. Anatomically, Cheselden described the clitoris as a ‘small spongy body, bearing some analogy to the penis in men’. But the description of its place is highly technical, stating ‘it begins with two crura from the ossa ischia’: although he does mention that this ‘proceeds to the upper part of the nymphaea’, this text did not help Anne understand the location of the clitoris.43

With both Mariana and Mrs Barlow, she tried to reach the ‘orifice of the womb’, but it is unclear whether she meant the hymen or cervix.44 She was intent on ‘devirginating’ Mariana, or breaking her hymen, in a way to triumph over Charles, her husband, who had not been able to accomplish the act. In 1825, she penetrated Mariana with her finger and was surprised to find no entrance into the womb; she did not understand, therefore, the nature of the tightly closed cervix. At other times, Mrs Barlow complained that Anne pressed so far against the ‘orifice of the womb’ that it was painful.45

The theory of male and female seed also fascinated Anne, who was very aware of female wetness during sex. To Mrs Barlow, she said, ‘in copulation I always used my finger to keep the parts open so that I could give them what came from me’.46 She and Mrs Barlow speculated what it would be like if Anne had a penis: ‘she said I must excuse her saying so but she thought if I had a little one meaning a penis what I emitted was not good enough to beget children it was too thin not glutinous enough to which I agreed’.47 One night in 1834, her partner, Ann Walker, complained, ‘I gave her no dinky dinky that is seminal flow.’48 This is interesting because it referred to debates about generation at the time. Earlier anatomy books, and especially popular works, debated whether the male or female fluids contained the seed that formed the embryo. By the 1820s new anatomical studies were proving the latter theory wrong; however, their work was still hotly contested.49

Anne also read widely to try to find more sophisticated and scientific understandings of anatomy than Aristotle’s Masterpiece. This was not just because she was searching for the clitoris: she was intensely interested in the body and in the medical treatment of her relatives, and followed the symptoms of her ailing aunt and uncle very closely. Although she never published anything, she was insatiably curious about science and pursued a systematic course of reading and lectures. As early as 1819 she wrote to the famed anatomist Cuvier and asked if she could study with him in Paris.50 By the 1820s, she was also very concerned that she had contracted venereal disease from her great love, Mariana, who in turn had contracted it from her husband, Charles Lawton. While this may have been simply thrush or another similar infection, Anne sought out experts, such as Guillaume Dupuytren, for treatment, including mercury.

In 1824 Anne asked local doctors in Yorkshire what she should read about, and they recommended Andrew Fyfe’s Anatomy and John Bostock’s Physiology.51 In contrast to the centuries-old Aristotle’s Masterpiece, and earlier more scientific anatomists, these newer books often ignored or slighted the clitoris. For earlier anatomists, the clitoris was interesting because its erectile tissue was similar to that of the penis. As Laqueur points out, the change in the understanding of fertilisation meant that the clitoris became less important, and also once the idea of female seed was discredited, then female sexual pleasure was also less significant.52 Fyfe’s Anatomy focused on the process of generation and buried the clitoris in a paragraph about the labia, noting that it produced the same sensation as the penis but without referring to pleasure. Unlike Aristotle’s Masterpiece, Fyfe began his description with the uterus, for he saw it as more important in the process of conception and birth. He also described the cervix in a way that might confuse it with the clitoris, which in other works was often compared to the penis. Fyfe claims ‘the under part of the Cervix projects into the Vagina, somewhat in form of the Glans Penis’.53 Similarly, while Alexander Monro, whom Anne read, mentions the clitoris in highly technical terms, he describes the womb and vagina first, and only mentions the function of the clitoris as ‘sensibility’.54 Bostock was up on the latest science. Trained in Edinburgh, he became fascinated by the chemical functions of the human body and trained in chemistry as well as medicine.55 Bostock was a physiologist, which meant that he was concerned with the mechanical, that is muscular or contractile, and nervous functions of the body, rather than simply describing anatomy. Although Bostock presented the debates about generation in detail, he was not concerned with sexual pleasure; he did not mention the clitoris.56

By 1828 Anne returned to Paris to attend lectures on anatomy, as well as botany, geology, zoology and mineralogy. In 1829–31 she wrote, ‘Surely my taste is decidedly for anatomy tho’ every part of science gives me so much pleasure I have always had difficulty in choosing that which seemed really to suit my natural inclination best.’57 Her studies also provided a welcome distraction from her romantic entanglements with three women, and she wrote, ‘What is there like gaining Knowledge? all else here below is indeed but vanity and vexation of spirit – I am happy among my books.’58

She purchased a skeleton for her rooms, and even dissected human body parts and foetuses, employing a medical student to teach her. Dissecting a human hand first made her feel ‘very queerish … somehow the cutting at a hand so like one’s own’.59 Studying anatomy was not something she could publicly discuss; she kept this information from Mariana, and when she told Vere Hobart, a prospective lover, Vere remarked ‘what pleasure you will have some time in dissecting me I merely said oh no even if I felt it a duty to have her opened I should not could not be there to see no one dissected those they had loved or had even much known’.60 In Britain dissections offended the devout, and only murderers could be legally anatomised. As a result, anatomists employed body-snatchers to find corpses to provide material for them,61 leading to several murders in Edinburgh, the infamous ‘burking’ of which Anne was well aware.62 In 1834, she noted that the people of Hull were ‘threatening to pull [the museum’s public dissecting rooms] down’.63 In contrast, since the Revolution, French doctors could dissect the bodies of diseased patients in charity hospitals.64 As Foucault points out, doctors thus exerted power over the bodies of the poor, who had to submit to become ‘spectacles’ in order to receive treatment.65

Anne enjoyed the intellectual and social ferment of early nineteenth-century Paris, where ladies attended scientific and medical lectures, in part to learn, and in part as a form of entertainment. She was omnivorously curious, attending lectures on botany, geology, chemistry, comparative animal anatomy and human anatomy. She was able to meet eminent lecturers such as Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire and Georges Cuvier, and even socialised with Cuvier’s wife and daughter. As Outram writes, the household and the natural history museum had porous boundaries. These eminent men often disagreed with each other fundamentally on the way to approach the examination of human and animal bodies, whether to follow form or function, similarities or differences on the surface or deep in the body.66 Anne was interested in much more than her own body, but she certainly mentioned lectures that touched on ‘generation’ or reproduction, even among molluscs.67

Studying anatomy in Paris exposed Anne even more to new approaches to anatomy and physiology.68 The older anatomy was interested in surveying and categorising all the organs of the body in a taxonomy, but the Paris School of Medicine focused on the functions of the tissues of the body.69 Bichat, who pioneered this approach, identified the different types of tissues that could be found across the body in various organs, so he would look beyond the individual organ to see its components. He also focused on the function of these tissues in terms of ‘contractability and sensibility’ that tied together the functions of the system of the body; furthermore, he organised his anatomy in terms of a ‘hierarchy’ of these systems.70 Paris anatomists did mention the clitoris, but these new ways of thinking about the body meant they sometimes downplayed it. Bichat describes the clitoris and notes the similarity in the tissue between the clitoris and the penis, with its corpus caverneaux, but in this he is echoing longstanding anatomical tradition. He noted that unlike the male genitals, which could be analysed ‘according to the principal phenomena of the function which they exercise; those of the woman do not lend themselves to this distribution’.71 Although Anne took out Bichat’s book from the circulating library and returned it, she does not mention any findings from it.72 She did read the works of his associates Pierre-Hubert Nysten, Pierre Béclard, and the brothers Hippolyte and Jules Cloquet.73

Even when she read these advanced anatomists, the necessary information was hard to find and decipher: it took a year and a half. Today, we can just look in the index or Google search a term, as I have done in this research. But French books had their tables of contents at the back and did not index them. Anne tended to read through books systematically, noting which pages she read each day, so it took some time to get to the end of the book – and to find information about female sexual organs, which even then was not entirely clear.

First, Anne found Nysten’s dictionary of medicine to be useful – and stimulating. In February 1830 she wrote in code, ‘Reading anatomy from 12 to 1 50/60. Chiefly dictionary, clitoris, etc., & at last, in trying if I had much of one, incurred a cross on my chair.’74 Nysten described the clitoris as something which is often touched, ‘titiller’, at the ‘partie superiore de la vulve’, composed of erectile tissue and analogous to the penis. However, this meant the ‘top’ or upper part of the vulva, so that Anne might have confused it with the top of the vagina.75

She then read Béclard, who followed Bichat’s discipline in emphasising function; instead of presenting his book as a visual tour through anatomy, he organised it by tracing the function of bodily fluids: ‘The human body, like all organised bodies, is composed of solid parts and of fluids, which have a similar composition, and continually change into each other.’ Furthermore, he also delineated sensations such as irritability that produce motion. Generation was another function produced by irritability: ‘the sensations and voluntary motions which accompany it, the motions of irritation, the phenomena of the secretion of the spermatic fluid and the formation of the ovula, those of the nutrition and grow the fecundated egg, are all seen to be more or less directly subject to the nervous action’. Béclard mentioned the clitoris, but it is buried in the text of a chapter on ‘Erectile tissue’ and its function and sensation are not described.76

Anne finally made the discovery in reading the works of the Cloquet brothers, but it took from June 1829, when she bought Hippolyte Cloquet’s Traité d’anatomie, to February 1831.77 Hippolyte Cloquet’s book was all text, and to identify the organs Anne had to purchase or obtain the very expensive plates of his brother Jules’s anatomy books. First, she had to plough through Hippolyte Cloquet’s dry prose about the heart and the brain; on 6 March 1830 she read on the urinary tract, and on 13 March 1830, she started reading a bit on the organs of generation, but soon nodded off.78 Hippolyte Cloquet, as usual, described the clitoris as resembling the penis because they were both composed of erectile tissue; he also noted that, like the penis, the corpus cavernus behind the clitoris had ‘an extraordinary number of blood vessels and nerves’. But these lists of anatomical parts did not help Anne conceptualise the location of the clitoris. She did borrow and eventually buy Jules Cloquet’s expensive book of plates, but it put her to sleep when she started to read it on 8 May 1830.79

It took another year for Anne to make the final discovery. On 25 January and 1 February, the comparative anatomist Cuvier lectured on the process of reproduction, including ‘the hymen uterus menstrual discharge and penis’, and she noted that half a dozen ladies, plus Cuvier’s wife and daughter, attended, undeterred by the topic.80 In his later published lectures, Cuvier described the vagina as analogous to the penis only in that it was made to receive the liquor of ‘fecundation’. However, like the anatomists, he mentions the clitoris briefly and as an afterthought. He states that it has ‘erectile tissue’ somewhat analogous to the penis, and that it was exquisitely ‘sensible’, but this is not related directly to sexual pleasure, unlike earlier anatomical descriptions.81

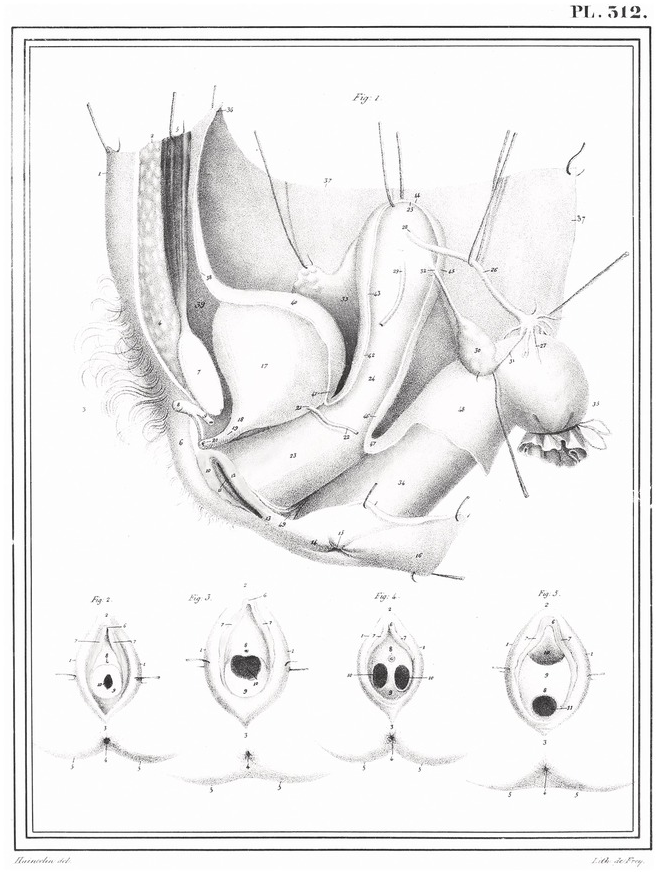

Anne decided to buy Jules Cloquet’s book for herself on 27 January. At the same time, she bought Sarlandière’s anatomy book.82 Finally, on 17 February 1831, she wrote that she fell asleep reading Cloquet, and then incurred a cross, noting, ‘it was from studying the female [parts of] generation and finding out distinctly for the first time in my life the clitoris’. 83 Anne must have put together the description in Hippolyte Cloquet’s written text with the plates in Jules Cloquet’s Anatomy.84 To figure it out, she would have to look at each plate, and go back to the description of the plates to find out which organ each number corresponded to. Since the clitoris was so small, not all the plates made this very obvious. But one side view did make it quite clear; the clitoris appears as a little protrusion from the nymphae, but it is quite distinct. The same day, she also read more in Sarlandière, who described the clitoris and the external organs as ‘organe de l’appétit vénérien de la femme’, separately categorising the vagina and the uterus. A plate on the previous page clearly labelled them. The organs of digestion are on the same page.

Figure 3 Manuel d’anatomie descriptive du corps humain: représentée en planches lithographiées by Jules Cloquet.

In reading these texts, Anne also had to contend with the fact that Parisian sources tended to link the clitoris negatively with sex between women. Bichat began his discussion of the clitoris by disapprovingly mentioning the problem of women with enlarged clitorises who engage in ‘vicious’ practices and become too masculine and lascivious.85 In his dictionary, Nysten noted that a M. Fournier had invented the word ‘clitorisme’ to diagnose those women with enlarged clitorises who ‘abused’ other women with them.86 If Anne had investigated this definition further, she could have found an entry in the Dictionnaire des sciences médicales (1813) that presented titillation of the clitoris in highly negative terms as leading to ‘bizarre tastes’ for relations between women, such as that indulged by Sappho, which would distract from the natural relations between women and lead to ‘bitter feelings’; it also led to excessive masturbation.87 Anne had to read such texts with all the tools of queer reading to take the information she needed without feeling as if she were tainted by such perversity.

Anne also read cultural and anthropological works that took a negative approach to women’s anatomy. For example, she read J.-J. Virey’s Histoire naturelle du genre humain and De la femme.88 Virey stressed that men and women were different in every way, and women were suited to the softer domestic world owing to their physiology. Anne did not take on Virey’s ideas about women’s soft and submissive nature; in fact, around the same time, she planned to write a book arguing that women of property deserved the vote. Virey mentioned the clitoris only in the context of puberty, and in more detail, in exotic and racialised tales of the so-called Hottentot Venus as well as oriental women with supposedly large clitorises.89 On 20 April, Anne read the very pages in which Virey mentioned the Hottentot Venus and the necessity in oriental countries of female circumcision for enlarged clitorises, and then spent half an hour in the closet touching her clitoris; the next day she tried to titillate it in order to enlarge it.90 Although Virey clearly meant accounts of enlarged clitorises to indicate racial difference and pathology, Anne found these accounts instead to be inspiring.

Virey probably learned of the Hottentot Venus from the pre-eminent anatomist Georges Cuvier. She was actually Sara Bartmann, a woman of KhoeKhoe heritage from South Africa, who had been taken first to London, then to Paris, to be exhibited on the stage as exotic. When she died, Cuvier obtained her body and dissected her, and then wrote a great deal about her supposedly elongated labia and clitoris, repeating these mentions in his book on anatomy that Anne read.91 He and other anatomists were pioneers of racist interpretations of human physiology.92 Anne also visited Johann Blumenbach in Germany, another scientist well-known for his racial theories.93 However, Anne seems to have simply ignored the racist implications of the anatomical works she was studying (although further transcriptions may reveal more of her opinions).94

What can Anne’s search for the clitoris tell us? This is a very unusual example of how a nineteenth-century person studied anatomy to understand her own body, and how it took so long for her, a well-educated and sexually experienced woman, to figure it out. On the one hand, she was so shaped by Aristotle’s Masterpiece and dominant phallic discourses that she was searching for the clitoris deep within her own and her lover’s vaginas. On the other hand, she used her tools of queer reading in searching for the clitoris, taking on negative depictions and turning them around – and getting turned on by them. At first, she thought she would find something about her own anatomy that was different, such as an enlarged clitoris, and that would explain why she was so attracted to women. But as she searched for the clitoris, she was also trying to find her lovers’ clitorises to give them pleasure, and to give herself pleasure; she saw herself as different from them, as masculine and usually not wanting to be touched, but also as similar, in sharing the same anatomy. For Anne, the search for the clitoris was part of her general tendency to study, document and control; she sought to explore her own body and those of her lovers in the same way as she mapped and controlled her land and her destiny, but the surrounding culture mapped sexual anatomy in a way that sometimes took her in a false direction.