1 Introduction

Weight gain and obesity are known risk factors for several diseases, including hypertension, insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular diseases (CVD), stroke, and some types of cancer [Reference Pi-Sunyer1]. Consequently, weight gain and obesity also affect morbidity and mortality, notably in cardiovascular disease patients [Reference Pi-Sunyer1, Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2]. There is therefore an urgent need to investigate the risk factors for weight gain and obesity, especially in a clinical context, where weight gain has an impact on patients’ medication adherence. Shin and colleagues [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2] found that patients gain an average of 2.45 kg during an inpatients psychiatric treatment. To reduce the chances of weight gain during psychiatric hospitalization, we need to determine the factors associated with weight gain that puts patients’ health at risk.

At present, there are several known factors that can influence weight or lead to weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment. One well-known risk factor is psychopharmacological medication use [Reference Dent, Blackmore, Peterson, Habib, Kay and Gervais3–Reference Sušilová, Češková, Hampel, Sušil and Šimůnek6]. In their review, Dent and colleagues [Reference Dent, Blackmore, Peterson, Habib, Kay and Gervais3] found that several psychotropic drug types, such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, anxiolytics and mood stabilizers are able to induce weight gain. In several pharmacological trials an association between a lower initial BMI and an increased weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment compared to initially obese or overweight patients could be found [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2, Reference Ness-Abramof and Apovian4, Reference Musil, Obermeier, Russ and Hamerle5, Reference Sušilová, Češková, Hampel, Sušil and Šimůnek6].

In addition, Shin and colleagues [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2] found that, in their American multi-racial sample, ethnicity had a significant influence on weight gain. Asian patients showed the smallest weight gain and BMI increase. In contrast, Afro-American patients showed the greatest weight gain and BMI increase. In line with these findings, Truong and Sturm [Reference Truong and Sturm7] found that in the U.S., non-Hispanic Afro-Americans gained weight faster than non-Hispanic whites. The investigated sample included different ethnic groups, but it remains unclear whether this effect is rooted in biological (e.g., genetic) factors.

However, differences in weight gain also have a cultural explanation: in many modern and industrial cultures, such as in the U.S., obesity has a negative connotation, and thus, the pursuit of weight loss has produced a major industry [Reference Brown8, Reference Brown and Konner9]. In contrast, obesity is seen as a sign of health and prosperity in many other cultures [Reference Brown8, Reference Brown and Konner9]. In traditional Nigeria, for example, high weight is considered as an indication of femininity, beauty and nobility [Reference Brown and Konner9]. Generally, it would seem that Africans see weight as evidence of good living. Also nutritional habits, availability of aliments, and financial opportunities may be factors which are associated with regional differences in weight gain.

Moreover, this difference in BMI change may be due to different clinical practices related to prescribing psychiatric medicines and the diagnostic process in these geographical regions because of different levels of development (for example unaffordable drug prices [Reference Buabeng, Matowe and Plange-Rhule10]) and cultural attitudes towards health [Reference Toftegaard, Gustaffson, Uwakwe, Andersen, Becker and Bickel11] or food [Reference Kumanyika12]. Additionally, Zito and colleagues [Reference Zito, Safer, Janhsen, Fegert, Gardner and Glaeske13] found differences in the prescription of psychotropic medication for children and adolescents even between the Netherlands, Germany, and the US, which are defined as developed countries. As reasons for these differences, the authors cite regulatory restrictions (such as government drug regulation and the availability and financing of services) and cultural beliefs [Reference Zito, Safer, Janhsen, Fegert, Gardner and Glaeske13, Reference Patel14].

In their systematic review Haroz and colleagues [Reference Haroz, Ritchey, Bass, Kohrt, Augustinavicius and Michalopoulos15] compared the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for Major Depression with the most frequent features of 170 study populations of 77 different nationalities. They found that the DSM model does not adequately reflect the construct of depression at worldwide levels, because the DSM model is based on research on Western populations. This may derive from different cultural perspectives on or different clinical manifestations of the psychiatric disorders [Reference Kirmayer16].

Based on these findings, we hypothesized that the geographic region of treatment would have an impact on BMI changes during inpatient psychiatric treatment.

In addition to that, we propose that the distribution of psychiatric medication and diagnoses differs among the various studied regions. In this context, we assumed that BMI changes during inpatient psychiatric treatment are influenced by the psychiatric medication and diagnoses that patients obtain [Reference Dent, Blackmore, Peterson, Habib, Kay and Gervais3, Reference Ness-Abramof and Apovian4, Reference Stubbs, Williams, Gaughran and Craig17].

Moreover, we assume that the BMI of psychiatric inpatients on discharge is higher than their BMI on admission, which in turn influences the BMI change, as reported in the study by Shin and colleagues [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2]. Thus, we expect patients who have a normal weight on admission to gain significantly more weight than patients who are overweight or obese on admission.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Experimental

The study was conducted in mental health care centres in Nigeria (Nnewi), Japan (Hamamatsu), Denmark (6 centers: Aalborg, Augustenborg, Odense, Skanderborg, Slagelse, Tønder), Germany (Düsseldorf) and Switzerland (Marsens). Patients were recruited from May 2003 to February 2006. All patients admitted to a treatment centre at the time of the study were invited to participate. If patients were admitted more than once, only their first admission was included in the study. A detailed assessment of the patients’ physical and mental health status was performed on admission and discharge and after three months or on discharge day, whichever came first. Diagnoses and their codes were based on the current ICD-10 criteria of the WHO (2003). Patients were given one of the following diagnoses: F1 (F10-19: Mental and behavioural disorders due to psychoactive substance use), F2 (F20-29: Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders), F3 (F30-39: Mood [affective] disorders), F4 (F40-49: Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders), F6 (F60-69: Disorders of adult personality and behaviour). The assessments were made according to routine clinical practice. Additional information regarding geographic origin and socio-demographic data was recorded. For a more detailed description of the methods used in the study see publications by Frasch and colleagues [Reference Frasch, Larsen, Cordes, Jacobsen, Wallenstein-Jensen and Lauber18], Larsen and colleagues [Reference Larsen, Andersen, Becker, Bickel, Bork and Cordes19] and Toftegaard and colleagues [Reference Toftegaard, Gustaffson, Uwakwe, Andersen, Becker and Bickel11].

2.2 Sample

We combined Danish, German, and Swiss patients into a Western European patients group.

As our analyses aimed to draw conclusions regarding weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment, we included the data of those patients who were admitted for at least five days and for whom weight and body mass index (BMI: calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; kg/m2) data were available. Of the originally 2,328 patients, 876 patients met this criterion for our analyses. Missing data regarding psychiatric diagnoses was due to technical errors.

2.3 Calculations

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were performed to check the normality assumption. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to reveal significant differences between two dependent variables (for example BMI on admission and on discharge), whereas Mann-Whitney U tests were used for independent variables (for example extreme group comparisons) and Kruskal-Wallis tests for the testing of more than two independent variables with Dunn-Bonferroni Post-Hoc tests (for example the effect of geographic region on BMI change). For correlations we used the Spearman’s rho. Moreover, a linear regression analysis was conducted to examine predictors for BMI change.

3 Results

For the demographic data and an overview over the BMI values and the duration of hospitalization, see Table 1.

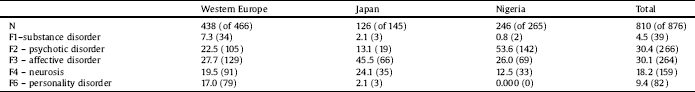

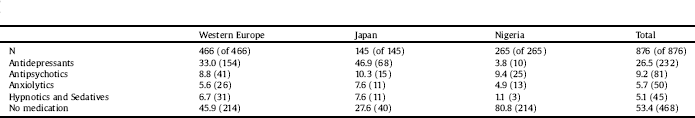

Of 876 patients, 483 were younger than the average age of the sample, and 393 patients were older. An overview of the psychiatric diagnoses and psychiatric medication use for the corresponding geographic regions can be found in Tables 2 and 3.

A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test revealed that the variables were not normally distributed; therefore, non-parametric tests were used. Concerning the BMI change, a positive value indicates weight gain, zero indicates no change, and a negative value indicates weight loss.

3.1 BMI

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed that the difference between the BMI on admission and the BMI on discharge was significant, with a higher median BMI on discharge (z = −9.684, p < 0.001). Because the descriptive data suggested that this result could be changed if the Nigerian patients were left out of the analysis because of their high BMI change, we conducted a Wilcoxon signed-rank test with only the Japanese and the Western European patients; this analysis also showed a significantly higher BMI on discharge compared with admission (z = −3.674, p < 0.001). To clarify a possible relationship between the duration of hospitalization and BMI change, a correlation analysis of the two variables was conducted. There was a non-significant positive correlation (Spearman’s rho) between the duration of hospitalization and the BMI change (ρ(874) = 0.006, p = 0.853).

We assessed the BMI change separately for the following groups and calculated the statistical significance of difference between the groups: 364 patients had an initial BMI above 25 kg/m2, and 512 patients had a BMI lower than 25 kg/m2. A Mann-Whitney U test indicated that the BMI change was higher for patients with an initial BMI lower than 25 kg/m2 (mean rank = 470.4, Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 [range = −7.26–9.59]) than for patients with an initial BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher (mean rank = 393.6, Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 [range = −16.38–8.35]; U = 76,856, p < 0.001). A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed a significant effect of BMI on admission on the BMI change (χ2(37) = 62.67, p = 0.005).

3.2 BMI and geographic regions

The median BMI change was calculated for the different geographic regions: The median BMI change for the Nigerian patients was Mdn = 1.03 kg/m2 (range = −10.04–9.59); for the Japanese patients Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 (range = −16.38–2.74); and for the Western European patients Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 (range = −11.10–8.35). A Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant effect of geographic region (Nigerian, Japanese, Western European) on BMI change (χ2(2) = 145.4, p < 0.001). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference between the BMI changes of Nigerian and Japanese patients (z = 7.560, p < 0.001) and between those of Nigerian and Western European patients (z = −11.86, p < 0.001).

An extreme group comparison (1. vs. 4. quartile) showed that the patients who were in the first quartile of BMI on admission (N = 219; BMI on admission ≤21.09 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = −1.98–9.59; mean rank = 241.07]) gained significantly more weight than the patients in the fourth quartile of BMI on admission (N = 220; BMI on admission ≥27.92 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = −16.38–8.35; mean rank = 199.0]; U = −3.669, p < 0.001). A comparison split for every geographic region revealed significantly higher weight gain among Western European patients in the first quartile (N = 116; BMI on admission ≤21.66 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = −0.78–5.10; mean rank = 128.6]) compared with those in the fourth quartile (N = 116; BMI on admission ≥29.01 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = −11.10–2.42; mean rank = 104.40]) of BMI on admission (U = −3.547, p < 0.001). For the Nigerian patients, a Mann–Whitney U test showed that the patients in the first quartile of BMI on admission (N = 66; BMI on admission ≤21.30 kg/m2; Mdn = 1.243 [range = −1.62–9.59; mean rank = 73.47]) had a significantly higher weight gain than the patients in the fourth quartile (N = 66; BMI on admission ≥27.51 kg/m2; Mdn = 1.021 [range = −10.04–5.55; mean rank = 59.53]; U = −2.094, p = 0.036), whereas a Mann-Whitney U test of the Japanese patients found no significant difference in weight gain between the first (N = 36; BMI on admission ≤19.12 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = − 1.98–2.43; mean rank = 39.81]) and the fourth quartiles (N = 36; BMI on admission ≤25.13 kg/m2; Mdn = 0.000 [range = − 16.38–2.74; mean rank = 33.19]; U = −1.373, p = 0.170).

Table 1 Demographic data, median BMI and duration of hospitalization.

Number of patients, gender and marital status of the patients from different geographic regions as well as median age, median BMI on admission (BMI1) and on discharge (BMI2) and the median duration of hospitalization. Percentage values (for nominal scaled variables) and medians (for interval scaled variables) are printed in bold type. Absolute values (for nominal scaled variables) and ranges (for interval scaled variables) are displayed in the brackets. Values do not add up to 100% of the total sample size due to missing data.

Table 2 Psychiatric diagnoses.

Percentage distribution (%) and absolute number (in brackets) of psychiatric diagnoses for the studied geographic regions. Values do not add up to 100% due to missing data.

Table 3 Types of medication.

Percentage distribution (%) and absolute number (in brackets) of types of medication for the studied geographic regions.

3.3 Psychiatric medication

A Kruskal-Wallis test with the psychiatric medication as a factor and the BMI change as an independent variable showed a significant effect (χ2(4) = 17.39, p = 0.002). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference in BMI change between patients who received antidepressants and those who were not medicated (z = 3.411, p = 0.006) and between patients who received antidepressants and those who took antipsychotics (z = 3.127, p = 0.018). A Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant effect of geographic region (Nigerian, Japanese, Western European) on psychiatric medication use (χ2(2) = 150.9, p < 0.001). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference in psychiatric medication use between Nigeria and Japan (z = −11.08, p < 0.001), between Nigeria and Western Europe (z = 9.932, p < 0.001) as well as between Japan and Western Europe (z = −3.999, p < 0.001).

In the whole sample, patients who received an antipsychotic medication did not show a significant BMI change compared with patients who did not receive antipsychotic medication (Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 [range = −10.82–9.38, mean rank = 447.2] vs. Mdn = 0.000 kg/m2 [range = −16.38–9.59, mean rank = 435.0]; U = 75,884, p = 0.493).

3.4 Psychiatric diagnoses

A Kruskal-Wallis test showed that psychiatric diagnoses had a significant influence on BMI change (χ2(4) = 56.76, p < 0.001). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference between the BMI change of F2 patients compared with every other diagnosis (F2 vs. F1: z = −3.627, p = 0.003; F2 vs. F3: z = 3.113, p = 0.019; F2 vs. F4: z = 5.849, p < 0.001; F2 vs. F6: z = 5.824, p < 0.001) and between F3 patients compared with F4 patients (F3 vs. F4: z = 3.147, p = 0.017) and personality disorders (F3 vs. F6: z = 3.680, p = 0.002). Furthermore, a Kruskal-Wallis test showed a significant effect of geographic region (Nigerian, Japanese, Western European) on psychiatric diagnoses (χ2(2) = 64.70, p < 0.001). A Dunn-Bonferroni post hoc test showed a significant difference between the psychiatric diagnoses given in Nigeria and Japan (z = −5.883, p < 0.001) and between those in Nigeria and Western Europe (z = 7.594, p < 0.001).

A multiple regression revealed that psychiatric medication, psychiatric diagnosis and the geographic region could explain a significant part of the variance in BMI change. Age and sex, however, could not explain a significant part of the variance. The result of the multiple regression is displayed in Table 4.

4 Discussion

Our hypothesis that geographic region would influence weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment was supported. Moreover, we found that weight on discharge would be significantly higher than weight on admission and that weight on admission would be positively related to BMI changes during inpatient psychiatric treatment.

Not only was there a significant difference between BMI on admission and discharge, but BMI on admission had a significant effect on the BMI change. We found that patients with a BMI lower than 25 kg/m2 gained significantly more weight than those with a BMI of 25 kg/m2 or higher; additionally, the (Nigerian and Western European) patients with an admission BMI in the first quartile gained significantly more weight during hospitalization than patients with an admission BMI in the fourth quartile. Japanese patients in the first and fourth quartiles of BMI on admission did not differ in terms of weight gain. The reason for this finding might lie in these patients’ generally lower BMIs and the substantially higher duration of hospitalization. Our results are in accord with Shin and colleagues [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2], who found that patients with a high body weight on admission gained less weight during inpatient psychiatric treatment than those with normal weight on admission. One can assume that in a developing or threshold country, patients weigh less due to their lower socio-economic status and tend to gain more weight during inpatient treatment due to conditions that differ from their daily lives. However, we can only speculate about socio-economic factors because we did not acquire data of that kind. In general, weight gain can be a sign of improved well-being during hospitalization [Reference Fava20]; however, it can also be a medical side effect [Reference Dent, Blackmore, Peterson, Habib, Kay and Gervais3]. Several factors of inpatient treatment could be responsible for this finding, including a lack of physical activity, a different daily routine, better nutritional supply and the initiation or change of medication within psychiatric hospital treatment settings.

Table 4 Sample regression table.

Sample regression table for BMI change. Beta is the standardized regression coefficient. Significant at the p < 0.05 level. *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

4.1 BMI and geographic region

The hypothesis that the geographic region influences weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment could not be rejected. A significant effect of geographic region on BMI changes could be found. The Nigerian patients (as an example for Western Africa) gained significantly more weight than the Western European and Japanese patients (as an example for Eastern Asia), who showed a significantly smaller weight gain. One can discuss regional and cultural differences concerning weight gain. Socio-economic status or different attitudes towards body weight and food [Reference Kumanyika12] might have caused these differences. For example, Brown and Konner [Reference Brown and Konner9] found that in modern achievement-oriented societies, such as the USA or Asia, a high body weight is socially stigmatized. In contrast, in Nigeria, high body weight in women is considered a sign of health and femininity [Reference Brown and Konner9]. Moreover, Sobal and Stunkard [Reference Sobal and Stunkard21] postulated in their review that in developing societies, there is a strong relationship between socio-economic status and obesity: People with lower socio-economic status are more affected by obesity which can also be applied to the comparison of industrial and developing countries. Furthermore, Nigeria is a quite poor threshold country, with a gross domestic product per inhabitant of $1.490 (nominal, 2011). By comparison, Germany has a gross domestic product per inhabitant of $44,999. Health care policy factors can also explain our pattern of results. This is especially interesting in terms of the significant effect of geographic origin on the prescription of psychiatric medications and the psychiatric diagnoses. The rate of non-medicated patients is highest in Nigeria, in our collective it has the highest rate of patients suffering from schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F20-F29), which often require medication. This difference may be due to differences in the availability and financing of services or to unaffordable medication [Reference Buabeng, Matowe and Plange-Rhule10, Reference Zito, Safer, Janhsen, Fegert, Gardner and Glaeske13]. For example, 47.8% of African countries have a mental health policy (World Average: 59.5%; South-East Asia: 70.0%; Europe: 67.3%) [Reference Saraceno and Saxena22]. In 78.9% of African countries, less than 1% of the total health budget is spent on mental health (World Average: 36.3%; South-East Asia: 62.5%; Europe: 4.2%) [Reference Saraceno and Saxena22]. Another striking fact is that 29.9% of African countries do not have three of the most common psychotropic drugs (Phenytoin, Amitriptyline and Chlorpromazine) required for treating mental disorders at the primary health care level, which is higher than the world-wide average of 19.4% (South-East Asia: 11.1%; Europe: 22.2%) [Reference Saraceno and Saxena22]. Additionally, the health care supply of mental health professionals is rarely met: for example, there are just 0.05 psychiatrists (average: 1.00; South-East Asia: 0.21; Europe: 9.00), 0.05 psychologists (World Average: 0.40; South-East Asia: 0.02; Europe: 3.00) and 0.04 social workers (World Average: 0.30; South-East Asia: 0.05; Europe: 2.35) per 100,000 people in African countries [Reference Saraceno and Saxena22]. This underlines the extent of the differences in health care supply among different geographic regions. Another explanation could be found in ethnical reasons. Ethnicity and genetics are a well known risk factor for weight gain and obesity [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2, Reference Filozof and Gonzales23]. These differences may base on physiological causes, such as genetic differences in the resting metabolic rate and a high respiratory quotient, which indicate low fat oxidation [Reference Filozof and Gonzales23]. However, possible generalizable ethnical factors are strongly confounded by local practice patterns and blending of ethnic groups within single countries.

4.2 BMI, psychiatric diagnoses and psychiatric medication

Another explanation for the mentioned results might be the psychiatric diagnoses. The results showed that patients with schizophrenia, schizotypal, and delusional disorders (F20–F29) gained significantly more weight during hospitalization than all other patients. This might be due to younger age of these patients and lower BMI due to negative symptoms. Moreover, schizophrenia patients often exhibit a sedentary lifestyle and poor quality of food [Reference Stubbs, Williams, Gaughran and Craig17, Reference Filozof and Gonzales23]. This result needs not necessarily be due to conditions of developing countries. For example Fleischhacker and colleagues [Reference Fleischhacker, Siu, Bodén, Pappadopulos, Karayal and Kahn24] investigated patients with first episode schizophrenia with a low BMI and of young age. He could show a significant weight gain even in the Ziprasidone group, which is an antipsychotic which was not associated to significant weight gain in many clinical trials examining mid-range age and BMI schizophrenia patients [Reference Nasrallah25]. Therefore we can conclude that younger age and lower BMI on admission are important factors regarding weight gain, also in Western European countries.

Moreover, as already mentioned, disease related factors can contribute to this result. However, compared with the study subpopulation that received no medication, antipsychotic medication had no significant influence on BMI in our study. Nevertheless, patients treated with antipsychotics gained significantly more weight than those treated with antidepressants. Patients treated with antidepressants gained significantly less weight than non-medicated patients. These results must be interpreted with caution. The fact that few Nigerian patients with F2 disorders received antipsychotic medication could confound this result. Among the regional groups, Nigerian patients were most likely to be F2 patients, non-medicated and have the highest weight gain. Therefore in Nigerian patients weight gain cannot be seen as a side effect, but may be due to different admission strategies, with more patients suffering from schizophrenia being hospitalized and depressive patients treated on an outpatient basis or not at all in Nigeria. Therefore our results concerning the different contributions of psychiatric diagnoses on weight gain could also be due to different admission strategies in geographic regions. As previously mentioned, health care policy or different local prescribing and treatment practices may contribute to this pattern and complicate the interpretation of our data.

4.3 Limitations and recommendations

We were able to show significant differences in weight gain, prescribed medication and psychiatric diagnoses across ten different treatment centres in three continents. We are aware that explanations for these differences are likely multifactorial with strong influences of not only ethnical affiliation but also sociocultural differences and such of health care systems and of the sociocultural background in general. The data did not allow for properly controlling for all of these factors (especially ethnicity) which certainly can be regarded as a shortcoming of our study. However, due to the confounding of design by several uncontrolled factors, we cannot draw conclusions on causality of our results. Further limitations of our study included missing data regarding the socio-economic status, ethnical background and other factors that could influence the pattern of the results [Reference Shin, Barron, Chiu, Hyun Jang, Touhid and Bang2]. Moreover, further information about the prescribed medication, such as treatment duration, dose and substance, is not available. Medication-induced weight gain differs between certain substances of the described medication types [Reference Dent, Blackmore, Peterson, Habib, Kay and Gervais3]. Therefore our results regarding psychiatric medication must be interpreted carefully. Nevertheless, the major strength of our study was that the patients were recruited from and examined in five different countries on three continents. Therefore, a reliable identification of cross-sectional differences during inpatient psychiatric treatment was possible. However, generalization is limited to the mentioned countries or at most to the certain region of Western Europe, Eastern Asia and Western Africa.

Recommendations for further research include a clarification of single local-specific practice patterns contributing to weight gain in psychiatric patients to reach global goals in mental health care, like improvement of treatments, expansion of access to health care, transformation of health systems and the development of human resource capacities [Reference Collins, Patel and Joestl26].

5 Conclusions

As we were able to show, geographic region, psychiatric diagnosis and prescribed psychiatric medication influence weight gain during inpatient psychiatric treatment. Therefore, we consider weight gain as a multifactorial phenomenon that is influenced by several factors. In conclusion, one can discuss socio-economic, cultural, local prescribing and treatment practices or access-to-care reasons for the found results.

Contributions

Authors KF, CL, WR, RU and PMJ worked on the study design and the implementation of the study. Authors CLA, JIL, GGB, BB, BAJ, SOWJ, CL, BM, JAN, WR, KJT, KLT, UAA, RU, PMJ and JC did the recruitment and acquisition of study participants. Authors CE, CLA, SP, KGK and KF worked on the data analysis and the interpretation of the data. Author CE wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final draft of the manuscript.

Funding

Eli Lilly supported the first planning meeting held in Aalborg, Denmark.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Author KF has received travel payments from Lundbeck.

J. Cordes was a member of an advisory board of Roche, accepted travel or hospitality not related to a speaking engagement from Servier, support for symposia from Inomed, Localite, Magventure, Roche, Mag & More, NeuroConn, Syneika, FBI Medizintechnik, Spitzer Arzneimittel and Diamedic, research and study participation funded by the German Research Foundation and the German Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, Foundation European Group for Research In Schizophrenia, ACADIA Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Europe Ltd. and EnVivo Pharmaceuticals.

Authors CE, CLA, SP, KGK, JIL, GGB, BB, BAJ, SOWJ, CL, BM, JAN, WR, KJT, KLT, UAA, RU and PMJ reported no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Eli Lilly for the support of the first planning meeting held in Aalborg, Denmark.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.