1 Overview

This case study examines a Chinese-Omani cooperation project in the Special Economic Zone at Duqm, Oman (SEZAD), and illustrates how its significance extends beyond the China–Gulf relationship with broader implications for trade and security in the wider region. It shows how a small fishing village followed the typical Gulf progress narrative of new infrastructure and skylines rising from the desert, and how this vision advanced in conjunction with increasingly Chinese-driven development. The case study demonstrates how a project that began as one of the ports along the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) has gained in importance as being at the intersection of security interests in the region.

With an area of 2,000 km2 and a coastline of 80 km, the SEZAD is currently the largest special economic zone in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) region. It is a strategically located transshipment point for goods moving between Asia, Europe, and Africa and provides a crucial node in facilitating global trade and connectivity. The Sino-Oman (Duqm) Industrial Park is a major industrial park that is being developed within the SEZAD and is expected to attract investment of around US$10 billion. It will focus on a variety of industries including energy, manufacturing, and logistics, with key sectors for investment including agriculture, fishing, oil and gas extraction, the processing of foods, agrifoods, petroleum and nuclear fuel, the manufacture of chemical products, rubber and plastic products, automobiles, and building and construction industries.

This case study first discusses the overall context and considers the investment environment of Oman as well as Oman’s relationship with China. It then concentrates on the SEZAD and highlights several aspects that make this case unique. These include the involvement of multilateral funding (namely, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), the involvement of Chinese provinces in the development of an overseas industrial park, and issues for China as it invests in a neutral country, Oman.

2 Introduction

In February 2022, toward the end of the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions, the world witnessed a unique event: European monarchs, the king and queen of the Belgians, inaugurating a port in the Indian Ocean. The Omani Port of Duqm ميناء الدقم) located in a sparsely populated Governorate of Al Wusta ٱلوسطى) which literally means “the middle” in Arabic), is poised to play a pivotal role in international trade and shipping today as part of the SEZAD, a Chinese-Gulf cooperative project. This mega project would not have been possible without economic investment from China. The Sino-Arab Wanfang Investment Management Ltd. (中阿万方投资管理有限公司) invested US$10 billion in the project that includes the tripartite urban arrangement of a port, an industrial park, and a residential district. Additional funding was provided by a Western consortium led by the Port of Antwerp, Belgium, with the project aiming to transform an unremarkable fishing village into a major industrial port city.

In the modern era, ports have undergone a transformation from being mere cargo-handling facilities to comprehensive industrial hubs with integrated infrastructure and associated complex contractual and legal frameworks. These state-of-the-art facilities are designed to optimize the process of receiving, storing, handling, and distributing goods in an efficient and timely manner.

While this concept is not new, the Port of Duqm is unique in its multifaceted strategic significance, which goes beyond the typical functions of a modern port. In fact, the largest investment in Duqm has been directed not only to cargo berths and terminals but also to a new city with its own industrial, residential, and tourist areas. Even considering the many Chinese-funded industrial parks across the world, this one is particularly ambitious, a fact which suggests that it is not merely a commercial investment by China but also a strategic decision.

Since the MSR encompasses strategically positioned ports that facilitate trade between Asia, Africa, and Europe, Oman’s position at the crossroads of three continents and three seas has ensured its role as a critical link in the MSR for centuries. Historically, the Omani maritime empire also controlled the vast trade routes of the Indian Ocean. In fact, two key ports of the 21st Century MSR, both heavily supported by Chinese investment, Mombasa and Gwadar, marked the original outermost boundaries of maritime Oman before they were transferred to Kenyan and Pakistani governance respectively.Footnote 1

Many things have changed since the empire. One thousand miles north of Mombasa, Djibouti port has become a contested ground for “great power” rivalries; the United States and four European countries have set up separate military bases there along with the first overseas Chinese base. Gwadar and nearby ports retain their strategic significance but now as nodes in China’s ambitious maritime trade network, the success of which has had varying effects on host countries as made evident, for example, by Sri Lanka’s debt crisis. Regardless of such disruptive events (the latest being Hamas’s attack on Israel and consequent responses taken by Houthis from Yemen), the Indian Ocean maritime routes remain crucial for global trade, with the Red Sea route alone accounting for around 30% of worldwide container traffic (more than US$1 trillion goods annually).Footnote 2 These routes are now coming under additional pressure with problems further north caused by Russian aggression in Ukraine and issues in the terrestrial Middle East as it struggles to find a new peaceful equilibrium.

Such chains of events in the region emphasize the possible role the SEZAD could play for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and worldwide, first because the terrestrial security issues of the Middle East tend to have a less immediate effect on neutral Oman and second because its coast remains far away from the heavily militarized territorial waters around the Horn of Africa and hotspots within the Red Sea where global trade routes can be disrupted.

3 The Case

3.1 Oman in the GCC

The Sultanate of Oman, a member of the GCC, is a small country with significant strategic importance in the region and to the world at large (for general details, see Table 3.3.1). It is situated at the intersection of three regions (South Asia, West Asia, and East Africa) and three seas (Arabian Sea, Oman Sea, and Indian Ocean). Consequently, Oman controls the Strait of Hormuz, a vital chokepoint for global oil shipments and other commodities. It is also an important link between the Indian subcontinent and the Horn of Africa, and Oman’s ports provide a convenient stopover for shipping between these two regions. This strategic location makes Oman an important partner for China, as China seeks to expand its economic and political influence in the region.

Table 3.3.1 Oman facts

| Area | 309,500 km2 (coastline 2,092 km) | Labor force | 2.259 million (2021 est.) |

| Population | 3,833,465 (2023 est.) | Foreign labor | About 60% of the labor force are nonnationals |

| Government type | Absolute monarchy (Sultan Haitham) | Unemployment/ youth unemployment | 3.12% (2021 est.) 4.6% (2021 est.) |

| Legal system | Mixed legal system of Anglo-Saxon law and Islamic law | Exports | US$46.324 billion (2021 est.) |

| Real GDP purchasing power parity (PPP) | US$155.028 billion (2021 est.) | Export partners | China 46%, India 8%, Japan 6%, South Korea 6% (2019) |

| Real GDP per capita | US$34,300 (2021 est.) | Imports | US$36.502 billion (2021 est.) |

| Ratings | Fitch: BB˗ (2020) S&P: B+ (2020) | Import partners | United Arab Emirates 36%, China 10%, Japan 7%, India 7% |

| Economic overview: high-income, oil-based economy; large welfare system; growing government debt; citizenship-based labor force growth policy; US free trade agreement; diversifying portfolio; high female labor force participation. | |||

In contrast to many of its neighbors, Oman is relatively peaceful and stable, with a long history of independent foreign policy, neutrality, and mediation. As a descendant of a powerful maritime empire, it has maintained close ties with both the Arabian and the Persian sides of the Gulf and these relationships have allowed it to play a crucial role in regional diplomacy, serving as a mediator between the GCC and Iran, as well as between the United States and Iran. The country is thus a key player in efforts to maintain stability and promote cooperation in the Gulf region.

Oman has undergone a period of modernization and development over the past five decades under the rule initially of Sultan Qaboos bin Said who transformed the country, diversifying its economic priorities away from oil and exploring new avenues for growth. His successor, Sultan Haitham bin Tariq, the head of state since 2020, has continued this progress by providing a vision document “Oman 2040” focused on five strategic goals: further economic diversification, strong and inclusive private sector growth, sustainable and balanced development, efficient and transparent government institutions, and skilled and competitive Omani human capital.Footnote 3

The future economic policy of Oman places significant importance on free economic zones (FEZs) as an investment instrument to achieve economic diversification and growth, facilitate international trade and exports, help Omani businesses to reach new markets, and create jobs for Omanis. Oman’s strategic location and well-developed ports, including the FEZs around them, contribute significantly to the country’s trade and economic growth. In 2020, Oman’s ports handled a substantial shipping cargo trade volume of US$7,369 million, including 5.2 million TEUs of containers,Footnote 4 18.4 million tons of liquid cargo, and 54 million tons of general cargo. The eight ports of Oman handle an annual average of 5,400 to 6,200 vessels, with Sohar, Salalah, Duqm, and the Port of Sultan Qaboos in Muscat being the most notable. The latter is also currently undergoing a gradual transformation to include a tourist port, enhancing its appeal in the region.

FEZs are special economic zones (SEZs) that offer a variety of incentives to attract foreign investment, including tax breaks, simplified regulations, and easy access to land and labor. However, SEZs and FEZs are not differentiated in Oman at the legislative level, in the Free Zones Law,Footnote 5 or in the decree establishing the Public Authority for Special Economic Zones and Free Zones (OPAZ).Footnote 6 The OPAZ lists only Duqm as a SEZ together with eight other strategically important entities it oversees including Al Mazunah Free Zone, Salalah Free Zone, and Sohar Free Zone. The terminological differentiation of Duqm’s status may suggest greater plans for the SEZAD.

3.2 China–Oman Relationship

The ancient MSR forged strong cultural and trade ties between Oman and China, laying the foundation for a modern relationship that blossomed during Sultan Qaboos bin Said’s reign. In 1978, the countries established formal diplomatic relations, recognizing the potential for mutually beneficial cooperation. The Sultanate actively participated in promoting cross-regional communication and interdependence. In addition to its strategic location, Oman is the fourth largest crude oil supplier,Footnote 7 reducing its dependence on traditional (coal) energy sources. Oman’s neutral foreign policy and shared commitment to the five principles of Chinese Foreign Policy and International Law provide China with a valuable partner in the Gulf region, facilitating dialogue and conflict resolution channels.Footnote 8 Oman’s efforts in maintaining maritime security in the Gulf of Oman and the Arabian Sea align with China’s goal of securing safe passage for its commercial vessels.

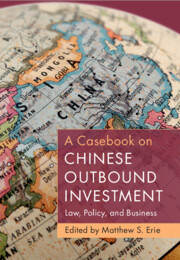

The trade volume between China and Oman has grown significantly in recent years (see Figure 3.3.1). In 2021, China exported goods worth US$3.13 billion to Oman, while Oman exported goods worth US$23.9 billion to China. In addition, there is a positive trend in cultural exchanges between China and Oman, with a recent increase in Chinese tourists visiting Oman and more Omani students studying in China.

Figure 3.3.1 Oman–PRC trade statistics

The China–Oman relationship is likely to continue to grow in the years to come. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) provides a framework for further cooperation between the two countries, and both sides are committed to deepening their ties.Footnote 9 Much of this framework rests on the multilateral relations with the GCC, which have been developing for decades and achieved significant success with regard to the penultimate round of the China-GCC FTA negotiations,Footnote 10 the GCC Single Customs Union, as well as the establishment of a number of Sino-Arab platforms for economic cooperation such as the biannual China-Arab States Expo and the China-Arab States Cooperation Forum.Footnote 11 These are the main “umbrella” entities for multiple thematic platforms of South-South cooperation,Footnote 12 in which Oman has a mandate. In this sense, the creation of the SEZAD has not been just a bilateral effort and strategic partnership between Oman and China but an outcome of significantly wider regional cooperation.Footnote 13

3.3 Local Labor and the Investment Environment

The vast majority of the Chinese projects in Duqm are carried out by migrant workers. The total migrant labor force in Oman is estimated to be more than 45% (1.6 million) of the total population in 2023, around 60% of which are migrants from India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.Footnote 14 The construction sector is the largest employer of migrant workers, followed by the manufacturing sector and the services sector.

The situation is similar across Oman, which, like its neighbors, has a foreign worker sponsorship scheme, the kafala system.Footnote 15 Under this system, in order to obtain a working permit in the country, a foreign worker needs a sponsor (a kafeel) who must be a local citizen. This sponsor often ends up controlling the foreign worker’s immigration documents, work permit, mobility, and even accommodation. The ethics and fairness of the working relations between the kafeels and the blue-collar migrant workers in the Gulf states has been subject to international scrutiny for some time.Footnote 16 In recent years, with the latest set of reforms in 2023,Footnote 17 the Omani government has implemented a number of progressive changes to the kafala system that has made it easier for workers to change jobs and leave the country without requiring their employer’s permission.

Apart from the labor reforms, the SEZAD investors also faced the challenge of bringing their own workforce from China as there were already many middle-age male migrant workers in the construction sector in Oman as well as alarming levels of youth unemployment.Footnote 18 It must be noted that along with the high number of migrant laborers, the Omani government is currently reviewing the quotas for the minimum number of local workers in the private sector. The goal is to achieve a gradual and sustainable increase in the so-called Omanization (تعمينال) of the private sector labor force. Although benchmarks vary according to industry, the overall categories include the following goals by 2025: professional and technical occupations, 80%; administration and clerical occupations, 60%; service occupations, 50%; trade and sales occupations, 40%; production and related occupations, 30%. Such sensitivity toward the local labor force might have a negative effect on Oman’s attractiveness for foreign investment, although in the case of the SEZAD, it seems this sensitivity has avoided problems, mostly due to the government’s public diplomacy efforts. However, such labor law restrictions could pose additional barriers in the future for Chinese companies hoping to hire local employees in Duqm. Owing to the remote location of the area (more than 500 km from major urban centers), there are not many Omanis willing to relocate to Duqm.

Similar to its Gulf neighbors, Oman used to have restrictive investment laws that imposed on foreign investors a minimum cap for investment volume of around US$500,000 per investor as well as restricted single corporate shareholder incorporation. In addition, laws required foreign investors to partner with an Omani company and limited the number of shares that could be owned by foreign representatives. Owing to the liberalization of foreign direct investment (FDI) legislation, the Commercial Companies Law (2019) allowed single shareholder incorporation,Footnote 19 and was followed by the new Foreign Capital Investment Law (2019),Footnote 20 which allowed simplified procedures for setting up wholly foreign-owned companies that permitted 100% share ownership in most types of business.

In addition to the more liberalized foreign investment rules that operate at the national level, the SEZAD offers specific incentives to investors such as no minimum registered capital and full foreign ownership, tax exemptions for thirty years, full repatriation of capital and profit, as well as free import or reexport duties. Even though land use is limited to fifty years, the duration can be renewed. The Sino-Oman Industrial Park is therefore at the heart of an advantageous free zone offering attractive incentives for foreign capital. The park has also received permission to build its own water and power plants, and products processed in the zone are regarded as local products for export. One-stop service centers provide businesses with the services they need, including registration, licensing, visas, and residence permits for expatriates. Such reforms are expected to work in favor of Chinese investors in Duqm, especially as they have pledged to invest in the SEZ to help attract additional FDI from across the globe.

3.4 Major Chinese Investors in Duqm

The Sino-Arab Wanfang Investment Management Ltd. is one of the major investors in the SEZAD. It is a Chinese company that was founded in 2015, has a registered capital of RMB 200 million, and is headquartered in the Ningxia Autonomous Region. It has a focus on investment and management in the Middle East region. Company subsidiaries were established under the leadership and with the support of the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR) Government, a provincial-level jurisdiction within the PRC, and include Ningxia Shunyi Assets Management Ltd., Ningxia Water Investment Group Co. Ltd., Ningxia Construction Investment Group, Ningxia Residence Group Co. Ltd., Yinchuan Yushun Oilfield Services Technologies Co. Ltd., Yinchuan Fangda Electric Engineering Company, and the Ningxia Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SME) Association.Footnote 21

In 2016, the Oman Wanfang LLC was formed as a joint venture company by the Sino-Arab Wanfang Investment Management Company and the SEZAD with the sole aim of developing and operating the Sino-Oman (Duqm) Industrial Park. The cooperation agreement between Oman Wanfang LLC and the SEZAD was signed on 23 May 2016 by Yahya Al-Jabri, chairperson of the SEZAD, and Ali Shah, chairperson of Oman Wanfang LLC.Footnote 22 As part of the comprehensive agreement for land lease development cooperation, Oman Wanfang was granted 1,172 ha of land for the next fifty years for the development of the Industrial Park. This park is divided into three sections: a heavy industrial area of 809 ha, a light industrial complex of 353 ha, and a five-star hotel and tourist area occupying 10 ha.

The total investment for the development of the industrial park is estimated to be US$10.7 billion, which is funded by Chinese companies and financed by Chinese banks. At initiation in 2016, ten projects worth more than US$3 billion had been signed by Oman Wanfang LLC and its investors from China. These included:

A building materials market.

A methanol and methanol-to-olefin project.

A power station.

A seawater desalination and bromine extraction plant.

A high-mobility SUV project.

A solar equipment manufacturing base.

A plant for the manufacture of oil country tubular goods.

A plant for the manufacture of nonmetal composite pipes used in oil fields.

A plant for the manufacture of steel thread frame reinforced polyethylene pipes and their parts.

A five-star hotel.

In addition to the direct investments made by Chinese companies there was also notable support extended by a multilateral body, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB).

3.5 AIIB Support

The AIIB, with headquarters in Beijing, has emerged as an alternative development finance institution. Given its focus on the Asian region as well as close ties with the GCC, in September 2023 the Bank established its first overseas office in Oman’s neighbor, the United Arab Emirates.Footnote 23 Even though the AIIB was established as a Chinese initiative, the PRC currently holds only 27% of its voting shares; the rest are owned by its member countries, with Oman being one of the founding members. Having a wide portfolio, the AIIB has already funded development projects in thirty-six of its member countries, including Oman, which was one of the first high-income countries supported by the AIIB.

The AIIB contributed a US$265 million sovereign-backed long-term loan.Footnote 24 Such an amount might look relatively modest in comparison to the Chinese private capital invested in Duqm. Yet, considering the timing and destination of the AIIB contribution, its loan was essential for securing the Duqm Port Loan and launching the SEZAD. In fact, the loan proved instrumental during the early days when the SEZ focused on the port and refinery and project work involved building port-related infrastructure such as access roads, terminal buildings, and operational zone facilities.Footnote 25 The project was successfully completed by the end of 2023,Footnote 26 and the AIIB assessed the degree of the project readiness positively: “reflected by the high quality of client staff and consultants” the project was implemented with a “high degree of transparency on construction arrangements.”Footnote 27 The stated indicators of the long-term loan are directly linked to the operational capacity and profitability of the Duqm port during a ten-year monitoring period from the date of completion.

It must be noted that the conditions of the contract were based on the construction laws of Oman as the host country,Footnote 28 and that an Environmental Assessment was conducted as required by the Omani authorities. The project also complied with the AIIB environmental and social safeguards, health and safety requirements, and the Construction Environmental Management Plan. The Environment and Social Policy low-risk category was assigned to the project as it was claimed to be implemented on reclaimed land, without land acquisition, resettlement,Footnote 29 or marine works. The SEZAD team received training from international procurement and financial management specialists on tendering, auditing, and best financial practices. All contractor variation orders were subject to approval by the SEZAD’s implementation unit.

Thus, the SEZAD has become a model project supported via different institutional layers, including international ones in the form of the multilateral financial institution AIIB as well as by private sector companies from the PRC. Interestingly, there is another layer of stakeholders that might be overlooked – at the regional level within the PRC – as Chinese companies that have invested in the SEZAD often have clear regional affiliations. In summary, it could be said that the SEZAD is an example of input from multilateral, national (e.g., government negotiations), regional (e.g., companies from Ningxia), and private sector levels.

3.6 Choice of Ningxia: Winning the Hearts and Minds of the Local Population

It may be surprising that the NHAR, one of the poorest inland areas of China, is playing an active role in the construction of the SEZAD given that it is landlocked in the middle of China. Ningxia has, in recent years, garnered a new life as the Chinese national government has branded it as the gateway to the Arab world and the successor to the historic Silk Road toward the Arabian Sea.Footnote 30 Ningxia is relevant not just because of its location but also because of its demographics. It is home to one of the ethnoreligious minorities in China, the Chinese Muslim or Hui people (回族). Their ethnic and linguistic ties to the Muslim world have been a significant factor in enabling investments along the Arabian coast.

The NHAR government has organized the biannual China-Arab States Expo since 2013 in Yinchuan, cosponsored by the Ministry of Commerce and the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade (which serves as a bridge in promoting trade and investment between China and Arab states). The Expo has also been an opportunity to select appropriate partnerships for international industrial capacity development from the Arab countries, showcasing common investment projects along the BRI, including the Sino-Oman Industrial Park.Footnote 31

The people-to-people exchanges associated with the Duqm development are not limited to high-level diplomatic exchanges but extend to people working within the SEZ. The core pattern is inbound migration of the host country population to China for cultural and educational exchanges as well as Chinese initiatives to support the development of training and professional development centers locally. It was announced that the Duqm project would help build the city, contributing not only to the development of Oman’s economic diversification but also to local employment including upgrading the professional skills of young Omani workers. This decision could be seen as both benefiting the local economy and enabling Chinese investors to meet the compulsory Omanization requirement while maintaining a skilled workforce in the Industrial Park.

An initiative to send 1,000 Omani students to China on Wanfang scholarships began in 2018 and funds students to train at the Ningxia Polytechnic in Yinchuan. Courses relate to petrochemical engineering, construction materials, computer software, technology, renewable energy, petroleum equipment, and economic management – thus following the economic profile of the Duqm Industrial Park by developing training courses specifically related to SEZAD skills requirements.Footnote 32

The choice of the NHAR with its historical ties with the Muslim world serves as an apparatus of soft power. Supporting cultural and educational professional training and taking account of the employment perspectives in a predominantly young population could be interpreted as supporting the positive image of China in Oman. Oman Wanfang LLC has further undertaken to build a school for children with special needs and facilitate community greening initiatives, such as planting trees, recycling waste, and using renewable energy sources. Such projects aim to establish a strong and sustainable partnership with the Omani government and people and are examples of very effective public diplomacy that rests on the shared values between two countries, in this case predominately religious values.Footnote 33

3.7 “One Province One Country” and Overseas Industrial Parks

The fact that all the major Chinese investors are from the NHAR appears to follow the noteworthy “one province one country” (一省一国) model. This is not an officially stated slogan of the Chinese government, yet it has been frequently used in the development context, especially with respect to the pandemic.Footnote 34 However, the slogan, and more importantly, the concept it signifies, had been used in the context of Chinese development before the pandemic, including by one of the investors in the SEZAD.Footnote 35 The matching of sovereign states with Chinese provincial and prefectural administrative units is a significant development in China’s industrial transfer policy, and, in the case of the SEZAD, the NHAR is not just transferring capital and technology to the Middle East but also transferring its own domestic institutions and business expertise to inform the setting up of the Industrial Park.

The timeline for selecting such cooperative ventures can be explored using the SEZAD as an example.

Selecting cooperative countries for overseas park construction:

Ningxia SME Association and Ningxia Expo Bureau organized multiple visits of Chinese private sector representatives to Arab countries.

Choice of Oman for the Sino-Arab Industrial Park; visits to potential locations in Muscat, Salala, and Duqm. Select the latter for the construction.

Strengthening the organization and leadership of industrial park construction:

Formation of the Sino-Arab Industrial Park construction coordination and promotion working group.

The working group promoted mechanisms involving representatives of the:

▪ Ningxia NDRC (the National Development and Reform Commission) (for formulation of the overall plan for the park);

▪ the Information Commission, the Department of Commerce, the Expo Bureau (for supporting its promotion);

▪ the Department of Finance (to study Omani financial regulation and policies);

▪ the Foreign Affairs Office (working with Omani partners and learning FDI regulations); and

▪ the Ningxia Branch of the National Development Bank of China, the Ningxia Branch of the Bank of China (access to finance for overseas investments).

Planning of the industrial park:

Ningxia DRC commissions the Foreign Economic Cooperation Department of the China International Engineering Consulting Corporation (CIECC) to prepare the master plan of the Sino-Arab Industrial Park in Duqm.

The CIECC Master Plan aims to:

▪ guide the infrastructure construction;

▪ attract investments from all over the world;

▪ plan industrial fields;

▪ lay out major projects; and

▪ drive enterprises from Ningxia and regions to go global.Footnote 36

Determining the areas and priorities for industrial park construction:

Cooperation agreement signed between the Ningxia Government and Oman on the industrial park approving the proposed layout of the park as well as the industries to promote given the resource allocation in the region, access to markets, and advantages of the Chinese manufacturing industry, promoting China’s international production capacity cooperation.Footnote 37

Selecting enterprises:

Only at this stage does Ningxia invite and select those private companies that are going to be primary investors in the industrial park as well as enterprises from other Chinese provinces that invest in individual projects.

Formulating work programs for the construction of industrial parks:

This stage includes initiating the construction projects in accordance with the master plan.

Such a process for international capacity development, and in particular the role of subnational or province-level actors, is a significant departure from the traditional approach to foreign investment, which has often been characterized by a top-down approach from international institutions. It is a novel approach, specific to China, and the interplay between the provincial entities and enterprises that took place in case of the SEZAD could be generalized to planning and policy approaches used for the other thirty-nine Chinese Overseas Industrial Parks (COIPs),Footnote 38 as the majority of them have strong provincial affiliations. By pairing its domestic administrative units with foreign countries, China is taking a more proactive approach to its foreign investment strategy, moving away from Western-led international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and adapting its approach to align more with multilateral development banks such as the AIIB. This gives China more control over the process of industrial transfer and allows it to tailor the process to the specific needs of the target country. Linking state investment funds and state offshore industrial associations with local government administrative units ensures that the capital and technology transferred to, in this case, the Middle East is used in a way that is beneficial to both China and the host country.

In terms of the normative or regulatory framework for this type of foreign investment and international development, there is no specific law that supports Chinese provincial enterprises seeking international cooperation and investments in a similar manner to the law that supports foreign firms investing in China’s provinces.Footnote 39 The main guiding legal text is the “Guiding Opinions of the State Council on Promoting International Cooperation in Production Capacity and Equipment Manufacturing,”Footnote 40 which includes four principles:

Expanding the scope and scale of cooperation and promoting the export of high-quality production capacity and equipment.

Improving the policy support system and creating a favorable environment for cooperation.

Strengthening the coordination and cooperation mechanism and enhancing the overall effectiveness of cooperation.

Promoting green development and fulfilling social responsibilities.

Those four principles can be illustrated using the SEZAD case since it is an example of the use of Chinese equipment and international production capacity in an internationalized investment environment and the attempt to promote new patterns of an open economy with optimizing export flows, while also promoting green development.

3.8 The Security Dimension

In addition to its strategic location, Duqm has a number of other qualities that make it a notable location for trade and investment. First, the port has a deepwater harbor that can accommodate large ships, and China is particularly interested in Oman’s expanding road networks and railway system.Footnote 41 These developments will connect the new Sohar Port and Free Zone to the existing Omani and GCC transportation corridors that extend into the UAE and Saudi Arabia. This will give Oman a competitive advantage over other established logistical and transportation hubs in the region.

Second, the SEZAD is characterized by a diverse portfolio of primary industries within the industrial zone, whether they concern petrochemicals, natural gas processing, oil refining, building materials, chemicals, or the halal food industry. Even those industrial plants that are not Chinese-owned might still serve Chinese economic security interests; it is very important to trace the movement of intermediary goods as well as determining the markets for the final products. Looking at the China–Oman trade statistics, since most Omani petrochemicals and crude oil are exported to the PRC, plants such as oil refineries should still be considered strategically important for China even though Chinese investors might not have any stake in the actual plant. It is likely that once the industrial park is fully operational, it might serve as an international platform for meeting China’s growing demand for the energy products from the Gulf. Thus, the multimodal connectivity that makes the SEZAD work must be considered as significant within the overall industrial manufacturing enterprise.

Third and perhaps most prominently, Duqm’s strategic location also has implications for regional security. The port is situated relatively near important geopolitical hotspots, such as Yemen, where Oman is mediating the ongoing conflict between the Saudi-backed coalition and Houthis, as well as the Horn of Africa. This has drawn attention to its potential military and security significance. The development of the port could have implications for the balance of power in the region, and it could also potentially be used as a base for military operations.

In 2017, just a year after signing the Agreement between Oman Wanfang and the SEZAD, Duqm became a focus for military cooperation between Oman and its allies. The UK Ministry of Defence, Oman’s major economic and security partner, announced the expansion of the UK Joint Logistics Support Base at Duqm by investing an additional US$31 million.Footnote 42 In 2018, this was followed by an annex to an existing maritime security memorandum of understanding (MOU) signed between India and Oman,Footnote 43 granting special access for the Indian Navy to Duqm port as well as to a dry dock and maintenance facilities. Also in 2018, the United States, which has the highest military naval presence in the Gulf,Footnote 44 signed a Framework Agreement with Oman expanding US access to facilities and ports in Salalah and Duq.Footnote 45 The agreement gave the US Navy berthing rights at Duqm for logistical and maintenance purposes. The maritime security cooperation between Oman and its Western allies goes beyond just granting access and includes joint naval training and anti-piracy cooperation.

Oman also maintains military cooperation activities with the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), including joint training and coastline security cooperation.Footnote 46 The military value of the Duqm port to PLAN, however, should be considered as very low. Even if we assume “dual-use” of the port,Footnote 47 it would still be of limited value to PLAN given that it already has a military presence much closer to the Bab-la-Mandab strait (between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa). PLAN has negligible (if any) operational control over the SEZAD port as it is neither owned nor operated by Chinese companies (in contrast to other ports, e.g., Gwadar or Dar as Salam).

Such a wide range of military partnerships and the utilization of Duqm for military purposes puts Oman in a situation similar to Djibouti, which has a comparable, if more permanent, coexistence of different military powers (although not because of its independent neutrality policy but driven by financial motivation). The resemblance of the SEZAD to Djibouti’s Doraleh Port lies not as much in the “dual-use” aspect but in the development pattern, specifically the import of the Shekou model (蛇口综合开发模式) in Djibouti.Footnote 48 Shekou, similar to Duqm, a small fishing village in Shenzhen in China’s Guangdong province, was transformed into a modern center using the port–zone–city model to develop the port infrastructure, an industrial park, and the adjacent urban zones.

3.9 The Shekou Model

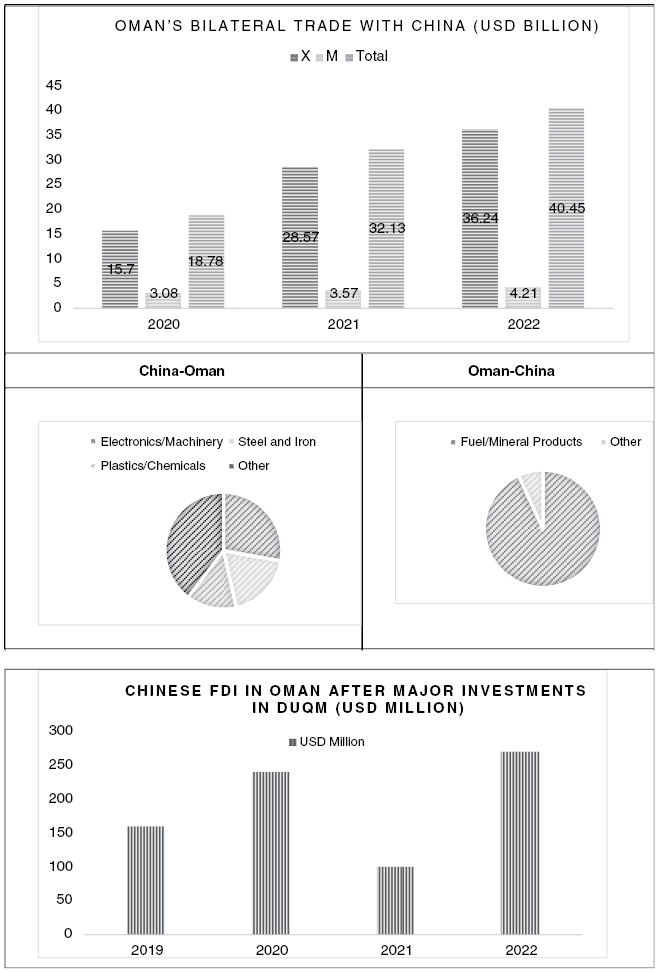

The SEZAD covers a multifaceted and integrated coastal urban-industrial space that is divided into eight separate and interconnected zones grouped into three main areas: port, industrial park, and city. This model envisages the initial development of the port with the subsequent gradual development of the industrial district and finally the residential area.Footnote 49 For the SEZAD (Figure 3.3.2):

Figure 3.3.2 Implemented and planned zones at the SEZAD

Maritime:

Port area: This zone includes a world-class deepwater port for shipping and maritime trade, the first phase of the 2.25 km long terminal with eight commercial berths. Two dry docks are to be installed for ship repair and maintenance, one of the largest facilities in the MENA, each 410 meters long, and a terminal with a total length of 2.8 km.

Fisheries center: This zone supports Oman’s largest 10 m deep fishing port, with two long breakwaters, a 1.3 km fixed berth, and six floating berths. It provides facilities for processing and marketing fish and seafood.

Industrial:

Industrial zone: This zone is designed to attract investment in a variety of industries, including manufacturing, logistics, and energy.

Logistics system: This zone provides transportation and storage facilities for goods and materials moving through the park, warehousing facilities, distribution centers, and cargo re-trading services. The airport, currently in operation on a single runway, is expected to be completed by 2024, with an annual design capacity of 500,000 passengers and 50,000 tons of cargo.

City:

New town: This zone provides housing, schools, and other amenities for the park’s employees and residents.

Central business district: This zone is the commercial heart of the park and is home to banks, offices, and other businesses.

Tourism and recreation area: This zone offers a variety of tourist attractions, such as beaches, resorts, and golf courses.

Education and training center: This zone provides training and educational opportunities for the park’s workforce.

The main similarity between the Shekou model and the SEZAD is the emphasis on foreign capital and the measures taken to attract it. Duqm stands out as an example of a more internationalized COIP, compared to other COIPs that are mainly oriented toward serving Chinese companies. Even though a large proportion of the project has been funded by Chinese private and development cooperation funds, European and Middle Eastern enterprises are supporting a number of infrastructure projects. For example, the port component is managed via a 50:50 joint venture between the Omani government and the Antwerp Port Group of Belgium (thus the special guests at its inauguration), the dry dock was built by Daewoo Shipbuilding Engineering Company of South Korea and is managed by the Oman Dry Dock Company, and the Omani Investment Authority is the sole manager of the fishing port. Similar patterns prevail beyond the maritime zone, such as a diverse range of stakeholders, which suggests that the development of the SEZAD should not be considered merely as a Chinese project.

4 Conclusion

The case of Duqm is an example of facilitated Chinese investment in a host country located in a globally strategic region of the world. The Chinese have benefited from favorable investment conditions while Oman has maintained its independent foreign and investment policy. Such an approach has manifested itself as a high degree of internationalization in the newly established port city and a potential influx of Western and GCC capital in the area where Chinese investments are concentrated.

As the Duqm port is not yet operational at full capacity, it is not clear at what point the return on investment will be high enough to make statements on the profitability of the project. Apart from the beneficial treatment for Chinese investors and preferential conditions for their investments, there are obvious strategic motivations for the Chinese, which are further enhanced by public diplomacy measures directed toward the local population and host country government.

5 Discussion Questions and Comments

5.1 For Law School Audiences

1. Given that the SEZAD is located in one of the most internationalized of the SEZs that Chinese companies are working in, what does the level of internationalization mean for dispute resolution? Many of the SEZAD contracts use local law, but would foreign investors have sufficient trust in local law for the purpose of resolving their disputes? If not, what are the alternatives? In discussing this question, consider China’s push to build Alternative Dispute Resolution both within and outside of China.Footnote 50

2. This case mentions different layers of funding for the development of the SEZ, ranging from provincial to multilateral levels. How do Chinese local administrative structures as well as multilateral strategies influence China’s trade and development policy with the Middle East?

3. The case also highlights that the projects had been implemented using the local law and complying with local industry standards. Is this also the case with other Chinese outbound investment projects you are aware of?

5.2 For Policy School Audiences

1. How does regional security shape the construction of the SEZAD? Did the planners of the SEZAD take such concerns into consideration, including what it means to have the industrial park near the highly militarized zone for (a) China, (b) the Omani government, and (c) the wider Gulf region? What are the risks and opportunities for the parties involved given that the Chinese have commercial activities in a port that is used by NATO? What are the possible implications of Chinese trade and development on Oman’s security interests?

2. It has been a decade since Xi Jinping proposed the grand goal of the Chinese foreign and development policy, the BRI.Footnote 51 How does this case study shed light on the soft power aspects of such initiatives such as the BRI and the relatively newer Global Development Initiative and Global Civilization Initiative?Footnote 52 What is the role and value of people-to-people exchanges, common religious/historical backgrounds, and education and training in this process?

3. What light may the SEZAD project shed on China’s possible policy choices in the MENA region? China has also played a decisive role in the normalization of the Saudi–Iran relations, which traditionally had been the domain of Omani foreign policy. It has also shown a strong stand on the recently revived conflict in Gaza. Given its interests, what is the possible policy line China could maintain in the regional conflicts of the Middle East? Given that Gulf–China relations have been elevated to the level of comprehensive strategic partnerships, and recognizing that the former relies extensively on US security and geopolitical assistance, what might the hard power projections look like in the greater Indian Ocean region in the case of potential escalation of the relationships between the great powers?

5.3 For Business School Audiences

1. When the SEZAD was first announced, it consisted of just the port and the refinery. It takes confidence by investors to invest at such an early stage of development. Nowadays, geopolitical risks play a crucial role in investment considerations, especially when it comes to the two superpowers, the United States and China, with ongoing technological rivalry and trade wars. What could be the geopolitical considerations for Western companies investing in the SEZAD as well as risks from the perspective of the Chinese companies when developing such an internationalized industrial park? To what extent would the Chinese-backed projects and commitments to the SEZAD have encouraged investment from the West and the Gulf region?

2. Duqm has been a major Chinese investment, yet the size of the FDI from China has fallen considerably (from billions to several hundred million US dollars) during the later stages of development. Currently, the focus for the SEZAD has shifted from heavily industrialized production and transportation of minerals toward more green energy and digital initiatives, supported mainly by British, European, and Korean investors. For example, the most sizable investments in the SEZAD in 2023 did not revolve around the Sino-Oman Industrial Park but rather focused on Hydrom,Footnote 53 which is coordinating national interest in green hydrogen and aiming to build the world’s largest production plant of renewable hydrogen by 2030. What would such a shift mean for China’s interests, including, potentially, its hydrocarbon trade? How would the medium-term investment horizon change for those Chinese companies that have been concentrating on the oil and gas production in the SEZAD?