Introduction

Drucker (Reference Drucker1986) states that an institution exists for a specific purpose, mission, and social function. He indicates that, ‘Without understanding the mission, the objectives, and the strategy of the enterprise, managers cannot be managed, organizations cannot be designed, managerial jobs cannot be made productive’ (p. 38). Thus, the starting point is the articulation of a mission statement, the determination of ‘what our business is and what it should be’ (Drucker, Reference Drucker1986: 57).

The value and benefits of a well-drafted mission statement have been touted by many (e.g., Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000; David & David, Reference David and David2003, Reference David and David2017; Mission and Vision Statements, 2018). But research on its impact on organizational, particularly financial, performance has been few (Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero, & Mas-Machuca, Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) and its results indeterminate (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008) likely due to the diversity in the studies' contexts and measures. This may question the very need for such a statement (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998), especially given the amount of time and effort invested in producing it and the risk of controversy and conflict in articulating it (Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1992). Nevertheless, Desmidt, Prinzie, and Decramer (Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011, Abstract) reinforce anew the value of mission statements with their meta-analysis study showing a ‘small positive relation between mission statements and measures of financial organizational performance.’

Early research on mission statements gravitated toward a managerial phenomenon-based approach, which was unsurprising given interest in mission statements began with practitioners (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018). This early research was focused on North American firms (e.g., David, Reference David1989; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987) and was descriptive (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998). Later research on mission statements expanded to cover various types and sizes of organizations (e.g., Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002; Spear, Reference Spear2017) and other geographies beyond North America (e.g., Attrill, Omran, & Pointon, Reference Attrill, Omran and Pointon2005; Lin, Huang, Zhu, & Zhang, Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019). It also increasingly became more quantitative (e.g., Bart & Hupfer, Reference Bart and Hupfer2004; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012) and used more theories in its investigations (e.g., Bartkus & Glassman, Reference Bartkus and Glassman2008; van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink, & Thijssens, Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008).

This study adds primarily to the increasingly quantitative, theory-based research on mission statements, by extending the investigation to the lesser-explored emerging market context, in this case the Philippines.Footnote 1 There is few research on mission statements conducted for emerging markets, like China (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019), India (Yadav & Sehgal, Reference Yadav and Sehgal2019), Malaysia (Amran, Reference Amran2012), and Sri Lanka (Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012). Unfortunately, there is no consensus on the mission statement–performance relationship (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012).

Expanding to new institutional contexts is valuable because there is evidence of geographical differences in the components (e.g., customer, product/service, location, etc.) and stakeholders (e.g., shareholder, customer, supplier, etc.) included in mission statements (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004). Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019) show how Chinese firms' mission statements are society-oriented and emphasize the social roles of a firm, while American firm's mission statements are market-oriented and emphasize customer and partner relationships. This society orientation may be due to the institutional voids firms in emerging markets face and may need to fill – weak institutions to support product, capital, and labor markets; misguided regulations; and inefficient judicial systems (Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu1997). Hence, (large) firms in emerging markets may attempt to fill and exploit these institutional voids as part of their corporate strategies and reflect as much in their mission statements. In fact, inclusions of ‘contribute to national development,’ and ‘nation building’ are seen in the mission statement of a few publicly listed corporations (PLCs) in the Philippines.

Additionally, emerging markets generally enjoy stronger growth than developed markets, and (larger) firms in said environment may profit from this growth by pursuing several opportunities simultaneously and not focusing their business on certain products, services, industries, and locations. This may reflect in a more open-ended mission statement, lacking in a sharp focus and specificity, as evidenced by a few mission statements from Philippine PLCs – ‘… to create long-term value for all our stakeholders,’ and ‘…make life better for every Filipino.’

This extension to an emerging market context further: (1) marries the practitioner-based component and theory-based stakeholder approaches in its investigation; and (2) empirically explores the mission statement–performance relationship and, in addition to this, investigates the association of the content and comprehensiveness of a mission statement with performance. This responds to the call to ground research on mission statements in theories (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) that can be subject to empirical testing. The component approach (David, Reference David1989; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987), originally used by businessmen in crafting their mission statement, argues that ‘a good mission statement should cover related components for it to play positive roles in the company's performance’ (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019: 4906). The stakeholder approach is a natural theoretical lens for research on mission statements given its predominant use in strategy management. It acknowledges that certain individuals or groups (stakeholders) affect the achievement of a firm's goal; and thus, stakeholder analysis is necessary as a firm decides on what it stands for (or its mission statement) (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). This study contributes to the literature by offering another view in the analysis of mission statements by considering the institutional voids, characteristic of emerging market contexts, in its exploration of the content and comprehensiveness of mission statements.

Review of literature

Mission statement

‘What our business is and what it should be’ (Drucker, Reference Drucker1986: 57) is the seminal definition of a mission statement. Several have added to this definition (e.g., Collins & Porras, Reference Collins and Porras1991; Vogt, Reference Vogt1994), yet the spirit remains the same. The statement's primary value is its ability to provide a firm a sense of direction, purpose, and focus (e.g., David & David, Reference David and David2003, Reference David and David2017; Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1992) – all critical to its long-term interest and survival (Pearce, Reference Pearce1982). Also, it ensures that key stakeholders and their legitimate claims are not ignored (Bart, Reference Bart1997b; Pearce, Reference Pearce1982).

A mission statement is an essential, foundational first step in the strategy management process (e.g., David, Reference David1989; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987). It is also the most formal, visible, and publicized portion of any strategy (Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987), communicating the organization's identity to stakeholders (Leuthesser & Kohli, Reference Leuthesser and Kohli1997) who are either inside or outside of a firm (Klemm, Sanderson, & Luffman, Reference Klemm, Sanderson and Luffman1991; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce, Reference Pearce1982).

The internal and external benefits of a mission statement are numerous. Internally, it can operationally and financially: (1) serve as a control mechanism (Bart, Reference Bart1997b; Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000); (2) guide wide range day-to-day decisions (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000; Mission and Vision Statements, 2018); and (3) inform long-range resource allocation decisions (e.g., Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003). Behaviorally, it can: (1) influence, inspire, and motivate employees, possibly providing them with a meaning for their existence and a sense of mission (e.g., Collins & Porras, Reference Collins and Porras1991; David & David, Reference David and David2003, Reference David and David2017; Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1992); (2) promote shared culture and values and offer standards of behavior (Bart, Reference Bart1997b; Klemm, Sanderson, & Luffman, Reference Klemm, Sanderson and Luffman1991) and performance (Mission and Vision Statements, 2018); and (3) guide actions and behaviors that are responsible (Pearce, Reference Pearce1982) and ethical (Mission and Vision Statements, 2018). Externally, it can enlist support, create closer linkages and enhance communications, and serve as a public relations tool (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003; Mission and Vision Statements, 2018) communicating a certain public image (Klemm, Sanderson, & Luffman, Reference Klemm, Sanderson and Luffman1991). It also may reveal a firm's ‘commitment to responsible, ethical actions in providing a needed product and/or service for customers’ (David & David, Reference David and David2017: 46), as well as project a sense of worth and intent that can be identified and assimilated by external stakeholders (Pearce, Reference Pearce1982).

Component approach

To help organizations craft their mission statements, early research focused on the components a mission statement should include (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008). The argument was ‘a good mission statement should cover related components for it to play positive roles in the company's performance’ (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019: 4906). Though researchers offered similar advice on the suggested content of the statements, they differed in the number, terminologies, and definitions of the components, limiting the comparability of studies and decreasing the benefits that could be realized with the replication of studies (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008). (See Alegre et al. [Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018], Bart & Baetz [Reference Bart and Baetz1998], Stallworth Williams [Reference Stallworth Williams2008], and Sufi & Lyons [Reference Sufi and Lyons2003] for summaries and further discussions on the different classifications of components.)

Two classifications of mission statement components have gained traction. The first comes from the seminal work of Pearce and David (Reference Pearce and David1987) and David (Reference David1989) which has nine components and has been used in several research outside of their own (e.g., Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008). These are customer, product/service, location, technology, survival, philosophy, self-concept, public image, and employee. The second comes from Bart which has more than twice the number of components than that of Pearce and David and has been primarily used in his research (e.g., Bart, Reference Bart1997a, Reference Bart1997b, Reference Bart2000; Bart & Hupfer, Reference Bart and Hupfer2004) and a handful of others (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002).

Stakeholder approach

The stakeholder approach to strategy (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984) recognizes that stakeholders, or ‘any group of individuals who can affect or is affected by the achievement of an organization's purpose’ (p. 53), play a vital role in a firm's success. This approach begins with the setting of a strategic direction, which includes the analyses of stakeholders, managerial values, and social issues, and incorporating all of these in the question ‘What do we stand for?’ (a mission statement) (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984: 83).

Conceptually, taking a stakeholder approach to mission statement: (1) recognizes that a firm's long-term survival and development are closely related to its stakeholders; (2) considers the stakeholders' needs, values, interests, and claims (Baetz & Bart, Reference Baetz and Bart1996; Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012); and (3) establishes the kind of relationship a firm wishes to build with them (Leuthesser & Kohli, Reference Leuthesser and Kohli1997; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012).

Practically, the stakeholder approach forces a firm to balance the competing claims of stakeholders, likely including only the (most) important stakeholders in the mission statement (Bart, Reference Bart1997b; Klemm, Sanderson, & Luffman, Reference Klemm, Sanderson and Luffman1991; Neville, Bell, & Whitwell, Reference Neville, Bell and Whitwell2011; Reynolds, Schultz, & Hekman, Reference Reynolds, Schultz and Hekman2006) and excluding the others – a divergence from the theoretical view of capturing as broad a range of stakeholders as possible (Freeman, Reference Freeman1984). Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997) offer a theory for identifying the important stakeholders based on the concept of saliency; it derives from the three stakeholders' attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency. The stakeholders highest on all three attributes are the most salient and dominant and likely to be recognized by the firms through their actions and possibly in their mission statements. (See Mitchell, Agle, & Wood [Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997] for further discussion on stakeholder saliency and typology.)

A mission statement is effectively a vehicle to communicate a firm's description (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000), a public declaration conveying how the organization (and its management) want to be perceived (Bartkus & Glassman, Reference Bartkus and Glassman2008), and a recognition of its salient stakeholders. It allows current and future stakeholders to determine their involvement with a firm (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000) and, if they agree with its mission, develop a relationship with the firm and align their individual objectives with those of the firm's – all of which can translate to a more intrinsically motivated stakeholder group (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2000). A mission statement thus provides a focal point and a sense of worth and intent for all stakeholders of a firm (David & David, Reference David and David2017).

Empirical studies on mission statement

Early research on mission statements gravitated toward a managerial phenomenon-based approach, highlighting the opportunity for more theory-based research (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018). It focused on North American firms (e.g., Bart, Reference Bart1997a, Reference Bart1997b; Bart & Tabone, Reference Bart and Tabone1999; David, Reference David1989; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987) and was descriptive (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998).

Research interest has since grown to encompass more: (1) geographies, such as Holland (Sidhu, Reference Sidhu2003), Malaysia (Amran, Reference Amran2012), Sri Lanka (Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012), the UK (e.g., Attrill, Omran, & Pointon, Reference Attrill, Omran and Pointon2005; Omran, Attrill, & Pointon, Reference Omran, Attrill and Pointon2002), and some even multiple geographies (e.g., Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008); and (2) types of organizations, such as small- and medium-sized enterprises (Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002; O'Gorman & Doran, Reference O'Gorman and Doran1999) and nonprofit institutions (e.g., Kirk & Beth Nolan, Reference Kirk and Beth Nolan2010; Spear, Reference Spear2017). Studies have also become more quantitative, exploring mission statements' association with innovativeness (Bart, Reference Bart1996, Reference Bart2000) and behavioral (Bart & Hupfer, Reference Bart and Hupfer2004) and financial measures (e.g., Amran, Reference Amran2012; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012). Lastly, more theories have been used in its investigation, such as theories on impression management (Spear, Reference Spear2017), legitimacy (Kirk & Beth Nolan, Reference Kirk and Beth Nolan2010; Mazza, Reference Mazza1999; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008), resource and stakeholder dependencies (van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008), rhetoric (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008), signaling (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Campbell, Shrives, & Bohmbach-Saager, Reference Campbell, Shrives and Bohmbach-Saager2001), and stakeholder (e.g., Bartkus & Glassman, Reference Bartkus and Glassman2008; Omran, Attrill, & Pointon, Reference Omran, Attrill and Pointon2002; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008).

The operationalization of research on mission statements follows several themes, its: (1) existence (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011); (2) inclusion of specific components (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008) or stakeholders (van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008); (3) existence and/or content's effect on employees (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) and performance (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008); and (4) development process (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011) and resulting impact on employee attitudes or organizational alignment (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011).

Hypothesis development

Existence of a mission statement

The existence of a mission statement may provide a firm numerous internal and external benefits, as earlier mentioned, e.g., offering it a sense of direction, purpose, and focus and acknowledging its stakeholders' claims. Despite these, not all firms have one. Defining a mission statement may be difficult, painful, and risky; and it may cause controversy, argument, and disagreement (Drucker, Reference Drucker1986), such as aligning diverse stakeholders' perspectives (Ireland & Hitt, Reference Ireland and Hitt1992). Developing one may require a lot of work, distracting management from operational matters (David, Reference David1989). Also, it may push a firm away from its comfortable status quo and illicit fears of revealing too much confidential and competitive information, among others. (See Ireland & Hitt [Reference Ireland and Hitt1992] for a detailed list of reasons.)

The most basic way to operationalize research on mission statements is to measure whether a firm has a mission statement, with the hypothesis that its existence, regardless of its form or content, positively influences performance (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011). Alegre et al. (Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) point out the criticisms of this type of studies: (1) their results are diverse, equivalent to the differences in the environmental contexts of and performance measures employed by these studies; and (2) they assume a direct association between mission statement and performance, likely overlooking mediating factors between these two constructs.

Empirically, evidence to support a mission statement–performance link is not plentiful and the early results indeterminate (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008), particularly in emerging markets (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012). Some studies have shown a significant relationship that is positive (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Rarick & Vitton, Reference Rarick and Vitton1995) or mixed (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998; David, Reference David1989) depending on the measures used, as well as a nonsignificant relationship (Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012). This has led Bart and Baetz (Reference Bart and Baetz1998) to question the value of a mission statement given the amount of time and effort invested in crafting one. Nevertheless, in a meta-analysis of 14 mission statement–performance studies, Desmidt, Prinzie, and Decramer (Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011, Abstract) reinforce anew its value, showing a ‘small positive relation between mission statements and measures of financial organizational performance.’

Based on the theoretical value of a mission statement and the empirical result of the meta-analysis, this study hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): The existence of a mission statement has a positive relationship with performance.

Content of a mission statement

Another way to operationalize research on mission statements is to determine if the content of a mission statement positively relates to performance, that is, to see if the inclusion of specific components (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018; Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008) or stakeholders (van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008), the two most used classifications (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019), influences performance. Alegre et al. (Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) also point out the criticisms of this type of studies: (1) they assume what is stated in a mission statement aligns with the real actions and beliefs of a firm; (2) they give equal weight and importance to all components (and stakeholders); and (3) they convey the idea that the more components (and stakeholders) mentioned the better (an issue tackled later under mission statement comprehensiveness).

Component approach

A component approach to studying mission statement takes on a managerial practitioner's perspectives. It focuses on empirical evidence and lacks a ‘theoretical corpus in which to be grounded’ (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018: 14). Despite this lack of theory development, the component approach still serves as a management tool, where important insights can be derived and used by practitioners as they develop and/or enhance their mission statements (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018).

Studies associating individual components with performance are not abundant and their results equivocal. There is no consensus on which components are associated with performance, and some studies have shown nonsignificant relationships for all components (Bart, Reference Bart1996, Reference Bart1997a). But the few studies that have shown a significant relationship for certain components skew toward a positive relationship toward ‘customer’ and ‘location’ (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008); firm's economic ‘survival’ (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008); ‘public image’ (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008); and concern for ‘employee’ (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008). However, some relationships are mixed with ‘philosophy,’ or the firm's basic beliefs and values, being both positive (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987) and negative (Amran, Reference Amran2012); and similarly so ‘self-concept,’ or firm's perceived strengths, both positive (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987) and negative (Amran, Reference Amran2012).

Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004) speculate that the possible lack of significant relationships between certain components and/or stakeholders and financial performance may be because the value is in the process of crafting a mission statement rather than the actual statement itself. They further state that the final mission statement may be relatively unimportant compared to the generation of ideas, determination of priorities, and other procedural benefits.

Nevertheless, Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004) also say a mission statement cannot be ignored given it is a public declaration and the possible negative impact of a ‘poor’ statement on a firm's perception and stakeholders, among others. Furthermore, a mission statement may need to include related components to positively influence performance (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019).

Additionally, studies reveal that the frequency of inclusion of certain components are equivocal and likely dependent on the studies' unique contexts – differences in industries (Bart & Hupfer, Reference Bart and Hupfer2004; David, Reference David1989), geographies (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019), profit/nonprofit motives, and time frames. Agreement only exists on two components: (1) self-concept is one of the most frequently included components across studies (David & David, Reference David and David2003; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008); and (2) technology is the least (e.g., David & David, Reference David and David2003; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003; O'Gorman & Doran, Reference O'Gorman and Doran1999; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008).

Following from this, firms in emerging markets may exclude certain mission statement components and gravitate more toward others. Facing larger economic growth potentials than firms in developed markets, firms in emerging market may avoid a sharp, articulated focus on certain products, services, industries, and location to maximize their participation in this growth. Also, likely lagging in technology to firms in developed markets, firms in emerging market may further exclude this already least included component in their mission statement. Apart from location (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008), these variables have not shown significant relationship with performance in prior studies. On the other hand, firms in emerging markets may fill institutional voids (Khanna & Palepu, Reference Khanna and Palepu1997) and have strong society orientation (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019) in their mission statements, as possibly seen with the often inclusion of their basic beliefs and values or ‘philosophy,’ public image, and concern for ‘employees.’ This is on top of the needed market orientation to ensure a firm meets its ‘customer’ needs, ensures economic ‘survival,’ and distinguishes its strength or ‘self-concept.’

Given these perspectives, study results, and an emerging market context, this study hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 2A: The inclusion of the components (H2Ai) customer, (H2Aii) survival, (H2Aiii) philosophy, (H2Aiv) self-concept, (H2Av) public image, and (H2Avi) employee in a mission statement has a positive relationship with performance.

Stakeholder approach

An (instrumental) stakeholder approach to strategy posits that, all things being equal, a firm practicing stakeholder management will achieve positive firm performance (Donaldson & Preston, Reference Donaldson and Preston1995), and empirical literature is generally supportive of this positive relationship (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013; Laplume, Harrison, Zhang, Yu, & Walker, Reference Laplume, Harrison, Zhang, Yu and Walker2021; Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, Reference Laplume, Sonpar and Litz2008; Phillips, Barney, Freeman, & Harrison, Reference Phillips, Barney, Freeman, Harrison, Harrison, Barney, Freeman and Phillips2019).

Thoughtful and well-executed stakeholder management, which includes treating the stakeholders well, managing their interests (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013), and likely also recognizing them and their interests in a firm's mission statement, can increase stakeholders' bond to and positive affiliation with the firm (Laplume et al., Reference Laplume, Harrison, Zhang, Yu and Walker2021). These in turn may help a firm create value through a variety of ways which ultimately translate to performance (Harrison & Wicks, Reference Harrison and Wicks2013). One, it may amplify a firm's legitimacy that can increase its stakeholders' support and environmental stability (Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, Reference Laplume, Sonpar and Litz2008). Two, it may enhance a firm's access to vital, needed resources which stakeholders may directly or indirectly control (resource dependence), or their centrality within a network can increase or withhold a firm's access to the rest of the network (Neville, Bell, & Whitwell, Reference Neville, Bell and Whitwell2011). Three, it may guide a firm on how to manage resources to achieve competitive advantages (resource-based view [RBV] of the firm) (Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell, & de Colle, Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and de Colle2010) and similarly indicate how creating long-term (not transactional) relationships with stakeholders can lead to valuable and intangible competitive advantages (Hillman & Keim, Reference Hillman and Keim2001).

The key issue, hence, is defining who is a stakeholder and identifying who to focus on. (See Friedman & Miles [Reference Friedman and Miles2006: 5–8] for a chronological summary of stakeholder definitions.) Considering the classic (instrumental) stakeholder definition of Freeman (Reference Freeman1984) and focusing on salience as a primary mechanism for stakeholder identification (Mitchel et al., Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997) lead to a focus on primary stakeholders – those identified by their economic relationship to the firm (customer, supplier, employee, and shareholder) – above secondary (all other) stakeholders. A focus on secondary stakeholders, or social issues not related to primary stakeholders, may not create value (Hillman & Keim, Reference Hillman and Keim2001), but at that same time they are becoming increasingly important to engage (Crane & Ruebottom, Reference Crane and Ruebottom2011).

Studies using a stakeholder approach for mission statements are less abundant than those that use a component approach and their perspectives (and results) more varied. Omran, Attrill, and Pointon (Reference Omran, Attrill and Pointon2002) determine no significant difference in returns between firms with a stakeholder-oriented mission statement and firms with a shareholder-oriented one. Desmidt, Prinzie, and Decramer (Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011: 478) indicate that ‘mission statement performance appears to benefit from a specific focus of the mission statement on the stakeholders served and the means to satisfy them’ (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998; Bart & Tabone, Reference Bart and Tabone1999). Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019) illustrate different stakeholders are emphasized by firms from different geographies, with mission statements from emerging market Chinese firms being more society-oriented, emphasizing the social roles of an organization, and those from developed market American firms being more market-oriented, paying more attention to customer and partner relationships. van Nimwegen et al. (Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008) show that the stakeholders firms are most dependent on are more frequently addressed in their mission statements and that the choice which stakeholder to include depends on different factors, such as the industry a firm is in. Lastly, the few studies that identify stakeholders in their studies most frequently include customer (Baetz & Bart, Reference Baetz and Bart1996; Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012) and have shown a significant positive relationship for certain stakeholders and performance: customer and shareholder (Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012), employee (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012), and society (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012).

Given the theoretical underpinning and empirical support for a positive relationship between stakeholder approach to strategy and firm performance, as well as the positive relationship of most individual stakeholders and performance shown by a few empirical studies, this study hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 2B: The inclusion of the stakeholder (H2Bi) shareholder, (H2Bii) customer, (H2Biii) employee, (H2Biv) supplier, and (H2Bv) society in a mission statement has a positive relationship with performance.

Comprehensiveness of a mission statement

Including a specific component or stakeholder in a mission statement may relate to financial performance, as shown by some studies. But it does not necessarily follow that a more comprehensive mission statement, one that includes more components or stakeholders, may result in even greater financial success, as posited by Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006). They say that adding more components or stakeholders may cause confusion and conflict, blurring what is priority and thereby affecting performance. Too broad a statement may attract stakeholders with clear goals of their own, possibly leaving a firm either: (1) floundering with no specific direction; and/or (2) coping to balance many competing claims and creating factions with its own interpretation of its mission statement.

Furthermore, equal balancing of stakeholders, which may reflect through the mention of many/all of them in a mission statement, contradicts theory and is difficult in practice (Laplume et al., Reference Laplume, Harrison, Zhang, Yu and Walker2021). A firm must allocate resource and attention in favor of the stakeholders that contribute most to value creation and give different weight to various stakeholders in its decision-making according to salience research (Laplume et al., Reference Laplume, Harrison, Zhang, Yu and Walker2021). Ultimately, a strategic narrowing is necessary, focusing on those stakeholders who affect a firm's strategic objectives (Friedman & Miles, Reference Friedman and Miles2006: 11); and in practice, many organizations do practice an unbalanced approach to stakeholders (p. 158).

Empirically, Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004) find that few firms include all stakeholders and most include only half of the components in their mission statements. David and David (Reference David and David2003) show that different industries develop different levels of comprehensiveness.

Further, evidence to support a mission statement comprehensiveness–performance link is mixed. Some studies have shown relationships that are inconclusive to nonsignificant (Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002; David, Reference David1989; O'Gorman & Doran, Reference O'Gorman and Doran1999) or significantly positive (Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987; Sidhu, Reference Sidhu2003) or even negative if comprehensiveness is captured by the length of a mission statement (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998). A comprehensive, inclusive mission statement is a longer mission statement; and Bart and Baetz (Reference Bart and Baetz1998) show that a relatively shorter mission statement has a significant positive association with performance, likely because they are easier to communicate and remember and encourage more focused effort.

Based on the argument that a more comprehensive mission statement may cause conflict and confusion and the theoretical and practical support for an unbalanced stakeholder approach to strategy, this study hypothesizes that:

Hypothesis 3 (H3): The comprehensiveness of a mission statement has a negative relationship with performance.

Methodology

Sample and data

This study's sample covers the 247 active PLCs in the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) as of December 31, 2018.

The Philippines is selected to extend research on mission statements in emerging markets. It is a fast-growing consumer-driven economy, with a 10-year average annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth of 5.5% as of 2018 (Schwab, Reference Schwab2019) and consumption comprising 70% of GDP (Pascasio, Dimafelix, Gamis, Chavez, & Robredo, Reference Pascasio, Dimafelix, Gamis, Chavez and Robredo2019). Amidst this large growth potential, firms operate in an environment with numerous institutional voids. Firms need to contend with poor roads, ports, and logistical infrastructures; high power costs; slow broadband connections; regulatory inconsistencies; corruption in both the public and private sectors; a complex and slow judicial system; slow and burdensome business registration process; and small, limited, and illiquid capital markets albeit a stable banking system (U.S. Department of State, 2019). But some (large) firms, many PLCs, may choose to exploit and/or fill these voids as evidenced by their broad pronouncements of industry- or nation-building in their mission statements.

The focus on PLCs is driven by their economic influence and data availability, and the lack of strategy management research focused on these firms. The total market capitalization of the PSE is equivalent to 74.43% of the country's GDP as of the end of 2018 (The World Bank, n.d.). Firms listed in the PSE also have the highest level of data transparency and disclosures and are required to annually disclose in their corporate governance reports if they have clearly defined and updated their vision, mission, and core values and where it can be publicly viewed (Securities and Exchange Commission [SEC], 2017). Lastly, despite the increasing practice of strategy management in large Philippine firms, likely PLCs, there is a paucity of strategy management research.

Data for this study were obtained from different sources. For each PLC's mission statement: (1) the author first visited its websites and searched for ‘Mission’ or ‘Mission Statement’ under the page ‘Home,’ ‘About Us,’ ‘Our Company,’ or its equivalent, or a search engine was used to find the statement (in March 2020); (2) if it was not available, the author next looked for ‘Mission’ or ‘Mission Statement’ in its 2018 annual reports; and (3) if it still was not available, it was assumed that the PLC had no mission statement or at least not one it wished to publicly share. For the PLCs' financial data, the author obtained these from Thomson Reuters, while for each of the PLC's incorporation date, to determine its age, it was taken from the PSE website.

Variables

This study's dependent variable is performance, and its measure is return on capital employed (ROCE) (Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012), which captures how a firm can efficiently turn its capital (both debt and equity) into operating profits. It is measured as annual earnings before interest and taxes divided by the difference between average annual total assets and average annual total current liabilities. It is averaged over the last three years as of year-end 2018 to moderate for any large fluctuations.

There are several independent variables used to test the various hypotheses put forward. First, the variable existence of a mission statement (Existence of MS) (H1) is captured by a binary measure of 0 if the PLC has no mission statement and 1 if it is visible in its website and/or 2018 annual report.

Second, the content of a mission statement is captured by the component and stakeholder variables. For the component variable, this study adopts and further reduces the well-used, parsimonious nine-component classification of Pearce and David to six components (David, Reference David1989; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987), given: (1) its continued relevance and presence in current mission statements (Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008); (2) the brevity of Philippine mission statements which averages 52 versus 112 words from Campbell, Shrives, and Bohmbach-Saager's (Reference Campbell, Shrives and Bohmbach-Saager2001) study of the top FTSE 100 firms; and (3) the likelihood of firms in emerging markets to exclude certain components and gravitate more toward other mission statement components given their context. For the stakeholder variable, this study focuses on two sets of stakeholders (Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and de Colle2010; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Barney, Freeman, Harrison, Harrison, Barney, Freeman and Phillips2019), a firm's: (1) primary stakeholders (shareholders, customers, suppliers, and employees) whose support is necessary for a firm to exist, who are intertwined with a firm's value creation process, and/or who a firm may have special duties toward; and (2) secondary stakeholders (lumped under the category society) who can influence a firm but who are not part of its operating core. Both the component and stakeholder variables are also captured by a binary measure of 0 if the individual component (H2Ai-vi) or stakeholder (H2Bi-v) is not in the mission statement and 1 if it is as determined from the content analysis. This measurement approach is comparable to prior studies using the component (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998; Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; David, Reference David1989; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987; Rarick & Vitton, Reference Rarick and Vitton1995) and stakeholder approaches (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008).

Third, the variable comprehensiveness of a mission statement (H3) is measured by counting the number of included components (# of Components) (Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002; David, Reference David1989; David & David, Reference David and David2003; O'Gorman & Doran, Reference O'Gorman and Doran1999; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987; Sidhu, Reference Sidhu2003) and stakeholders (# of Stakeholders) as determined from the content analysis.

Lastly, three control variables have been chosen from the few mission statement regression studies and among several variables that have been tested. These three measures have shown to be the most relevant in the model's fit. Like ROCE, all control variables are averaged for the last 3 years as of year-end 2018 to moderate for any large fluctuations. Firm Size is the log of average annual total assets, and it is expected to have a positive effect on performance (Attrill, Omran, & Pointon, Reference Attrill, Omran and Pointon2005). Firm Leverage is the quotient of average annual total liabilities and average annual total equity, and it is expected to have a negative effect on performance (Attrill, Omran, & Pointon, Reference Attrill, Omran and Pointon2005). Firm Age is the difference between December 31, 2018, and the date of a firm's incorporation, and its relationship with performance is indeterminate as indicated in the review article of Rossi (Reference Rossi2016) on firm age.

Content analysis

This study uses content analysis, an often-used research method in the study of mission statements (e.g., Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Kemp & Dwyer, Reference Kemp and Dwyer2003). The results of the content analysis are subsequently used for descriptive and statistical analyses.

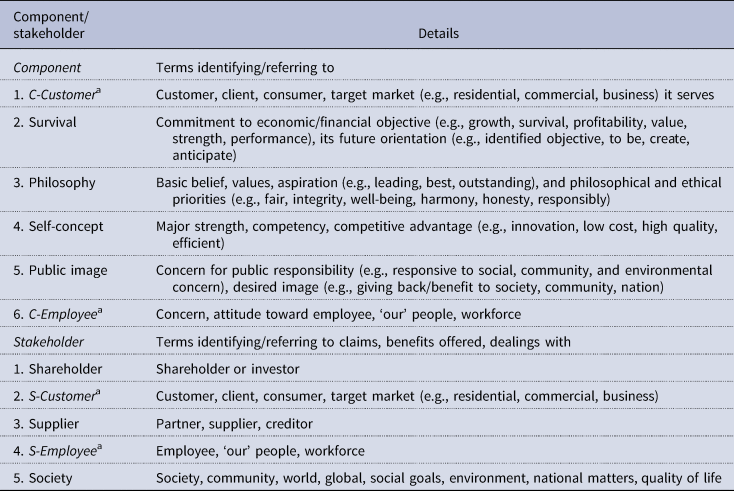

Table 1 enumerates this study's coding terms, which are adopted and slightly revised from the detailed coding terms used by Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004: 395–396).

Table 1. Component and stakeholder coding terms

a C refers to component approach and S to stakeholder approach.

Source: Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004: 395–396).

Note the presence of customer and employee in both the component and stakeholder coding terms, distinguished by the upfront addition of the letters C and S to the terms, respectively. There are significant differences in the coding of C-Customer and S-Customer, with S-Customer encompassing more than just identifying and making a reference to the customer which C-Customer only does. S-Customer may also include the benefits offered to the customer, e.g., the type of product/service it offers the customer. There is hardly any coding difference between C-Employee and S-Employee.

These coding terms were shared with the other coder, along with other relevant literature on mission statements and its contents, and the PLCs' mission statements. A preliminary round of coding was conducted on a handful of mission statements to test the coding terms. The author and the other coder independently recorded whether each PLC's mission statement contained each of the nine components and the five stakeholders using the coding terms. They then discussed their results, resolved any coding differences, and revised the coding terms accordingly. A certain component or stakeholder was judged to be present in a mission statement when both the author and the rater agreed. Coding proceeded independently for the rest of the mission statements. Interrater reliability levels were acceptable (Scott's pi = .836, Cohen's kappa = .837, and Krippendorff's alpha = .836).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses in past mission studies were rather simple, using: (1) correlation analysis (e.g., Bart & Tabone, Reference Bart and Tabone1999; Sufi & Lyons, Reference Sufi and Lyons2003; van Nimwegen et al., Reference van Nimwegen, Bollen, Hassink and Thijssens2008); and (2) test of statistical difference between two groups (e.g., Bart, Reference Bart2000; Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma, & Herath, Reference Dharmadasa, Maduraapeurma and Herath2012; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008) or more (Omran, Attrill, & Pointon, Reference Omran, Attrill and Pointon2002; Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012).

This study uses both correlation and cross-sectional, multiple regression analyses (e.g., Attrill, Omran, & Pointon, Reference Attrill, Omran and Pointon2005; Kirk & Beth Nolan, Reference Kirk and Beth Nolan2010; Sidhu, Reference Sidhu2003). Regression offers the benefit of exploring many variables simultaneously.

Results

Descriptive results

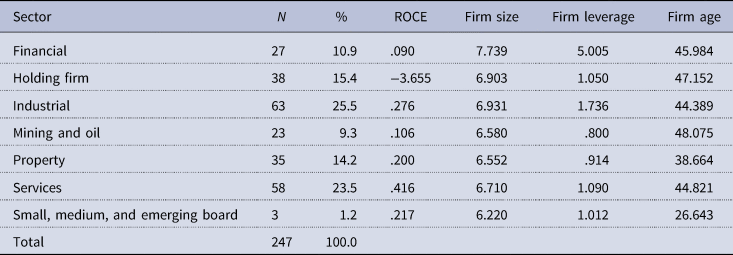

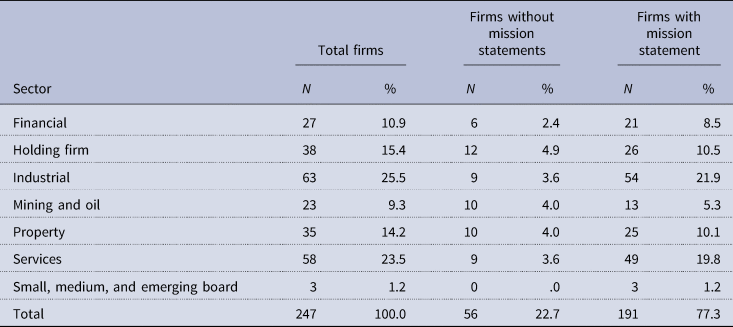

Table 2 describes this study's sample, and Table 3 indicates the existence of a mission statement. The industrial and services sectors: (1) have the largest number of PLCs, comprising close to half of the total; (2) are the highest performers in terms of ROCE; and (3) have the most firms (>80%) articulating a mission statement. Overall, only 191 of the 247 (77.3%) PLCs have a mission statement. Of the 56 (22.7%) PLCs classified as having no mission statements, 24 have either their mission and vision combined, mission and values combined, or mission, vision and values combined. Because of the difficultly of disentangling these PLCs' pure missions from the combined statements, they were excluded in the count of firms with mission statements.

Table 2. Profile of PLCs, means

Table 3. Existence of a mission statement

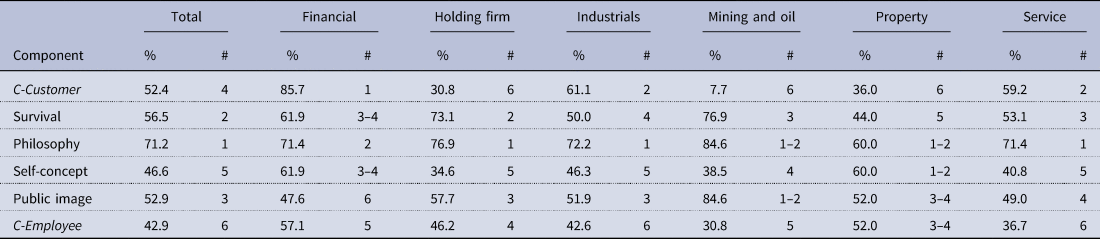

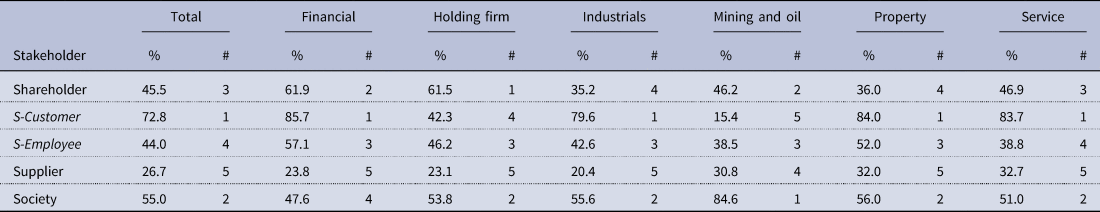

Tables 4 and 5 disaggregate the content of a mission statement by components and stakeholders, respectively.

Table 4. Component breakdown

Note. The column # refers to the component's rank in terms of frequency of inclusion in the mission statement.

Table 5. Stakeholder breakdown

Note. The column # refers to the stakeholder's rank in terms of frequency of inclusion in the mission statement.

In terms of components, the most frequently included are Philosophy and Survival, and the least are Self-Concept and C-Employee. The ranking of components, in terms of frequency of inclusion, differs across sectors. But they are at least directionally similar except for a handful of striking differences from the financial and property sectors, indicating possibly their unique contexts (Bart & Hupfer, Reference Bart and Hupfer2004; David, Reference David1989). The financial sector has C-Customer ranked higher at 1 (vs. total of 4) and Public Image at 6 (vs. total of 3). The property sector has Self-Concept ranked at 1–2 (vs. total of 5) indicating the need of the PLCs in the sector to distinguish themselves from competitors, C-Employees at 3–4 (vs. total of 6), and Survival at 5 (vs. total of 2).

In terms of stakeholders, the most frequently mentioned is S-Customer like prior study results (Baetz & Bart, Reference Baetz and Bart1996; Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004; Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012), and the least is Supplier. Directionally the results are similar across the sectors except for a handful of differences. The holding firm has Shareholder ranked at 1 (vs. total of 3) indicating this stakeholder is likely the most critical and salient for their success; and this sector, together with the mining sector, has S-Customer ranked at 4 and last, respectively (vs. total of 2), indicating this stakeholder is probably the least critical and salient for their success. Lastly, the banking sector has Society ranked at 4 (vs. total of 2).

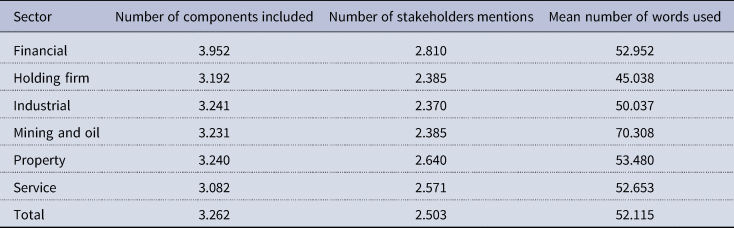

Table 6 shows the comprehensiveness of a mission statement, which on average contains half the number of components and stakeholders. This is in line with Bartkus, Glassman, and McAfee's (Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004) findings that few firms include all stakeholders and that most firms include only about half of the components. The average length of a mission statement is 52 words, less than half the average of 112 words, in Campbell, Shrives, and Bohmbach-Saager's (Reference Campbell, Shrives and Bohmbach-Saager2001) finding in their study of the top FTSE 100 firms. Except for the longer mission statements in the mining sector (M = 70 words, +43%), the level of comprehensiveness is similar across sectors contrary to David and David's (Reference David and David2003) finding that they differ by industries.

Table 6. Comprehensiveness of a mission statement, means

Statistical results

Correlation results

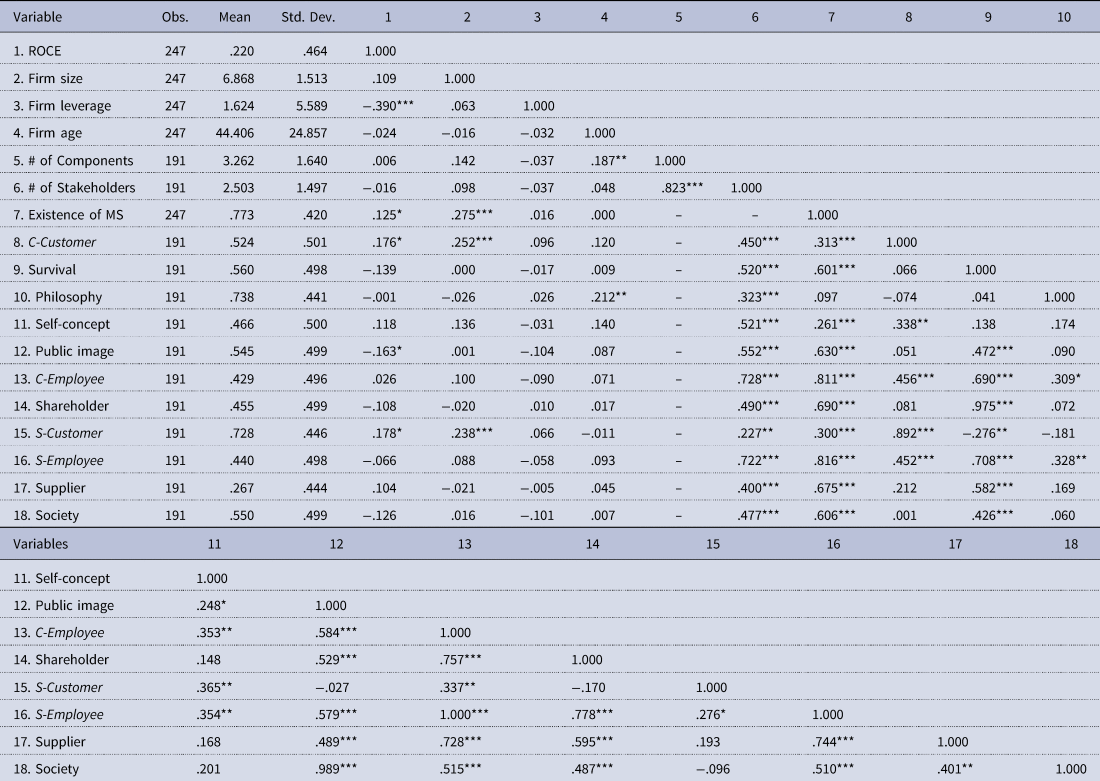

Table 7 contains the correlation analysis. Given the data values are a mix of continuous, discrete, and binary measures, different correlations needed to be computed – Pearson correlation for the continuous and discrete measures, point biserial correlation for the binary variables with continuous and discrete measures, and tetrachoric correlation for the binary variables. ROCE reflects significant relationships with Firm Leverage (r = −.390, p < .001), Existence of MS (r = .125, p < .05), and the inclusion of C-Customer (r = .176, p < .05) and Public Image (r = −.163, p < .05) for the component approach and S-Customer (r = .178, p < .05) for the stakeholder approach. Correlation coefficients for Existence of MS cannot be computed for the # of Components and # of Stakeholders, nor the individual component and stakeholder, because the measure does not vary; only when there is a mission statement can these individual components and stakeholders be present and counted. As expected, significant and at times large correlations exist between the # of Components and # of Stakeholders and the individual component and stakeholder which comprises the count. There are also some significant and large correlations between the individual component and stakeholder, such as C-Employee and S-Employee (r tet = 1.000, p < .001) and Public Image and Society (r tet = .989, p < .001); note these measures are used in two separate regression analysis, i.e., the component and stakeholder approaches. Lastly within the same approach there are some significant and large correlations, such as Public Image and Employee (r tet = .584, p < .001) for the component approach and Shareholders and Suppliers (r tet = .744, p < .001) for the stakeholder approach; and for these, multicollinearity needs to be computed in the separate regression analysis.

Table 7. Correlation table

Note. C refers to component approach and S to stakeholder approach; variables 8–13 are part of the component approach, and variables 14–18 are part of the stakeholder approach.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Regression results

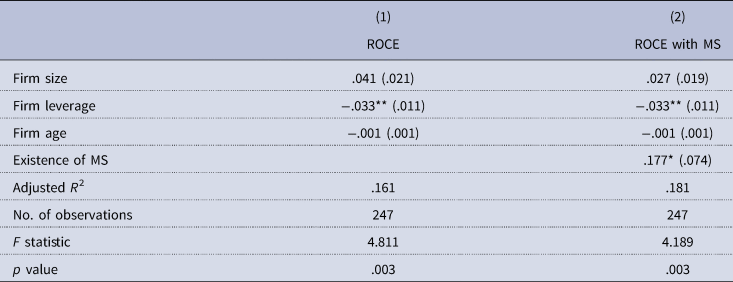

Existence of a mission statement

Table 8 demonstrates the mission statement existence–performance relationship. The Existence of MS is positively and significantly associated with ROCE (β = .177, p < .05) like the results of the correlation table (r = .125, p < .05). Its existence also increases the explanation in the variance of ROCE moderately (adjusted R 2 = .181 [+.020], p = .003). Lastly, the directions of the control variables are as predicted, but only Firm Leverage is significant (β = −.033, p < .01); and multicollinearity is not a concern (mean VIF = 1.04 for regression 2).

Table 8. Existence of a mission statement

Note. Standard errors in parentheses; constants estimated but not reported.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Two robustness checks on the mission statement–performance relationship were conducted. First, additional variables were added in the regression to control for Sectors and Firm Investments, defined as the quotient of annual capital expenditure divided by average annual total assets averaged for the last 3 years as of year-end 2018. The Existence of MS (β = .139, p < .10) remained positive and significant, albeit at a lower significance level, and the two additional control variables were nonsignificant. Second, return on assets (ROA) was instead used as a measure of performance, and the Existence of MS was also positive and significant (β = .065, p < .01). Results may be provided upon request from the author.

The results align with the theoretical value of a mission statement and empirical results of prior studies (Amran, Reference Amran2012; Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011; Rarick & Vitton, Reference Rarick and Vitton1995), as well as support H1.

Content of a mission statement

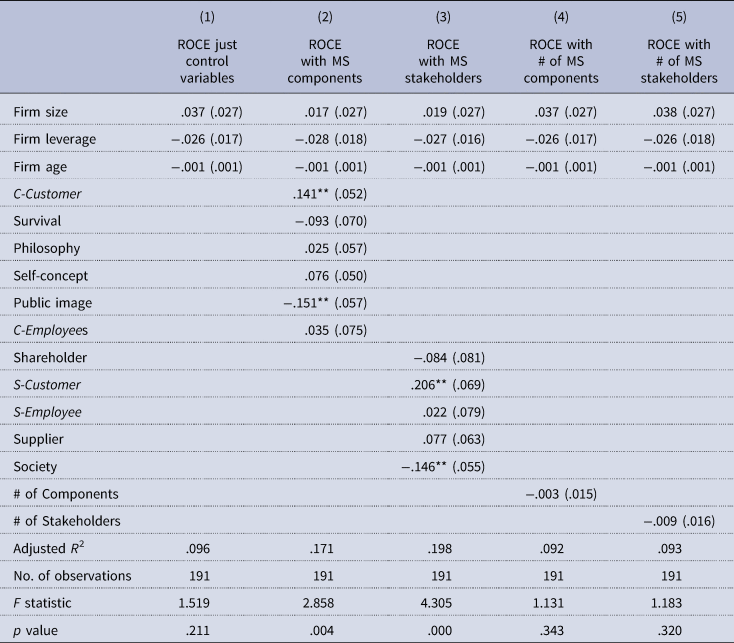

Table 9 shows the mission statement content–performance relationship (regressions 2 and 3), as well as the mission statement comprehensiveness–performance relationship (regressions 4 and 5).

Table 9. Content and comprehensiveness of a mission statement

Note. Standard errors in parentheses; constants estimated but not reported; C refers to component approach and S to stakeholder approach.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

ROCE is impacted significantly and positively by C-Customer (β = .141, p < .01) consistent with H2Ai but negatively by Public Image (β = −.151, p < .01) contrary to H2Av for the component approach (regression 2); this is like the results of the correlation table C-Customer (r = .176, p < .05) and Public Image (r = −.163, p < .05). The rest of H2A is rejected given the lack of statistical significance and at times opposite effects found (H2Aii, Survival).

ROCE is also impacted significantly and positively by S-Customer (β = .206, p < .01) consistent with H2Bii but negatively by Society (β = −.146, p < .01) contrary to H2Bv for the stakeholder approach (regression 3); this is like the results of the correlation table S-Customer (r = .178, p < .05) and Society (r = −.126, p < .10). The rest of H2B is rejected given the lack of statistical significance and at times opposite effects found (H2Bi, Shareholder).

The inclusion of components almost doubles the explanation in the variance of ROCE (adjusted R 2 = .171 [+.075], p = .001) (regression 2), and the inclusion of stakeholders more than doubles it (adjusted R 2 = .198 [+.102], p = .000) (regression 3). The directions of the control variables are as predicted but are nonsignificant; and multicollinearity again is not a concern (mean VIF = 1.23 for regression 2 and 1.30 for regression 3).

The same two robustness checks were conducted on the mission statement content–performance relationship. First, adding the two control variables, Sectors and Firm Investments, kept the significance and direction of the original results – C-Customer (β = .123, p < .05) and Public Image (β = −.156, p < .01) for component and S-Customer (β = .177, p < .05) and Society (β = −.161, p < .001) for stakeholder approaches; the two additional control variables were nonsignificant. Second, using ROA as the measure of performance, only the inclusion of the component C-Customer (β = .016, p < .10) remained positive and significant. Results may be provided upon request from the author.

Given that concepts overlap in these two approaches as seen from the correlations in Table 7 of C-Customer and S-Customer (r tet = .892, p < .001) and Public Image and Society (r tet = .989, p < .01), it is unsurprising to see the alignment of their regression results in terms of direction and significance. The Public Image, as a component, tackles not only the image a firm wants but also its public, social, community, and environmental responsibilities, which are precisely the matters of interest to the Society as a (secondary) stakeholder.

These results align with prior studies on components and stakeholders. For the component approach, prior studies show similar statistical significance for Customer (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008) and Public Image (Palmer & Short, Reference Palmer and Short2008; Pearce & David, Reference Pearce and David1987; Stallworth Williams, Reference Stallworth Williams2008) albeit in a positive direction, contrary to the study. For the stakeholder approach, prior studies show similar statistical significance for Customer (Peyrefitte, Reference Peyrefitte2012) and Society (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2006) albeit in a positive direction, contrary to this study.

Comprehensiveness of a mission statement

Though the # of Components (regression 4) and # of Stakeholders (regression 5) are negatively signed as hypothesized, they are nonsignificant. The correlation table has hinted this possibility given the small, negative, and nonsignificant correlation results; the regression was carried out to verify how the exogenous variables move together.

The results align with past studies that show no relationship (Analoui & Karami, Reference Analoui and Karami2002; David, Reference David1989) and reject H3.

Discussion

This study explores the mission statement–performance relationship in Philippine PLCs and shows that the existence of a mission statement, as well as the inclusion of Customer as a component and a stakeholder in a mission statement, positively and significantly influences performance. However, the inclusion of Society as a stakeholder and Public Image as a component in a mission statement negatively and significantly influences performance. Lastly, the comprehensiveness of a mission statement has no effect on performance.

The theoretical value of the existence of mission statements is empirically supported by this study. This study, thus, enlarges the body of empirical work, particularly in the emerging markets, that supports the value of a sense of direction, purpose, focus, and the internal (operational, financial, and behavioral) and external (support, linkages, and public relations) benefits of a mission statement. It also provides empirical support that there is value, beyond compliance, to the Philippine regulator's insistence that a PLC discloses its mission statement.

Certain inclusions in a mission statement are identified by this study to be associated with performance. Moreover, the use of two lenses in studying the content of a mission statement, the component and stakeholder approaches, has proven relevant given the reinforcing results. First, the identification of Customer (as a component) and a firm's commitment to this stakeholder have a significant positive association with performance. Second, tackling social, community, and environmental interests in a mission statement has a significant negative association with performance as shown by the inclusion of the component Public Image and the stakeholder Society. Moreover, the stakeholder approach proves valuable in explaining why certain inclusions in a mission statement have such effects on performance.

The Customer is overall the most frequently included stakeholder in a mission statement (73%) and within the top three in most sectors. This may be unsurprising in a consumer-driven economy such as the Philippines. Its inclusion in the mission statement also has a significant positive impact on performance.

The Customer is a primary stakeholder whose support is necessary for a firm to exist and whose value creation process is intertwined with that of the firm (Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and de Colle2010; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Barney, Freeman, Harrison, Harrison, Barney, Freeman and Phillips2019). A firm acknowledges the saliency of this stakeholder (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997) by including it in its mission statement and ideally by building a relationship with it (Hillman & Keim, Reference Hillman and Keim2001). Relative to other stakeholders, the customer's power over a firm, the legitimacy and urgency of its claim, as well as its ability to confer legitimacy (Laplume, Sonpar, & Litz, Reference Laplume, Sonpar and Litz2008), makes it a dominant stakeholder (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997). Hillman and Keim (Reference Hillman and Keim2001) show that building and investing in a long-term relationship with a primary stakeholder, of which the customer is one, can lead to the creation and/or enhancement of competitive advantages (RBV). This desire for a long-term relationship may reflect in a firm's mission statement, considering the customer's interests and acknowledging its claims on the firm; and if the customer agrees with all these, s/he may then choose to support the firm, translating ideally to its improved performance.

On the other hand, not all stakeholders positively impact performance as seen with Society's significantly negative impact on performance. The Society is overall the next most frequently included stakeholder in a mission statement (55%) and within the top two in majority of the sectors; this society orientation of mission statements mirrors the results of Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019). But unlike the Customer, which can be clearly delineated, Society is a more amorphous group of communities with broader interests in the environment, society, nation, and quality of life, to name a few. In an emerging market with numerous institutional voids like the Philippines, some (large) firms, many PLCs, may choose to exploit and/or fill these voids and reflect such efforts in their mission statement, with inclusions such as ‘environmental and social upliftment,’ ‘contribute to national development,’ and ‘nation building.’

Society is a secondary stakeholder that can influence a firm but that is not part of its operating core (Parmar et al., Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and de Colle2010; Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Barney, Freeman, Harrison, Harrison, Barney, Freeman and Phillips2019). It is a discretionary stakeholder that may possess the attributes of legitimacy, that may at times have the power to influence a firm (e.g., regulator, government), but that has no urgent claims on it – making it less salient than customers (Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, Reference Mitchell, Agle and Wood1997). Furthermore, Barney and Harrison (Reference Barney and Harrison2020) point out that the stakeholder theory is different from corporate social responsibility (CSR) which refers to things like environment and society. They point out that environment is not human, and society is best studied at the unit of analysis of the sociologists. For the stakeholder approach, they say a better focus is on corporate responsibility targeted at the primary stakeholders, such as providing a good product at a fair price to the customer, paying suppliers justly and timely, and treating employees well. Also, Parmar et al. (Reference Parmar, Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Purnell and de Colle2010) say that CSR does not have much to say on how value is created, casting it as an afterthought to the value creation process of stakeholder management or alternatively casting it as the primary criterion that supersedes profits. Lastly, Hillman and Keim (Reference Hillman and Keim2001) show that participation in social issues is negatively associated with shareholder value.

Contributions

This study primarily replies to the call to further ground research on mission statements in theories (Alegre et al., Reference Alegre, Berbegal-Mirabent, Guerrero and Mas-Machuca2018) that can be subject to empirical testing. It does so by focusing its investigation on the lesser-explored emerging market context and by offering another view that considers the institutional voids, characteristic of this context, in its exploration of the content and comprehensiveness of mission statements.

By combining the theoretical stakeholder and practical component approaches in the study of mission statements, reinforcing results are produced. Further, the stakeholder approach, with its concepts of primary and secondary stakeholders, stakeholder saliency and its typology, and long-term relationship building to build competitive advantage (RBV), provides a rich explanation of why the inclusion of customer and society has opposite effects on performance.

The results from this new emerging market context reinforce Lin et al.'s (Reference Lin, Huang, Zhu and Zhang2019) finding that mission statements in said context may be more society-oriented and may emphasize the social roles of a firm. It also echoes the results of Hillman and Keim (Reference Hillman and Keim2001), this time in an emerging market context, that the focus on primary stakeholders, in this study's case the customer, may produce beneficial results, but the focus on social issues, in this study's case the secondary stakeholder society, may not. The reality is firms in emerging markets need to adjust their strategy to fill and exploit the numerous institutional voids they face and, in the process, possibly taking on more social roles. However, there are risks, as shown by this study, that a society-oriented mission statement can negatively influence performance, perhaps because it overextends the firm's sense of purpose and diffuses its focus.

Additionally, this study reassures management that there is value in investing the time and effort and surmounting any controversy or conflict in the process of articulating a mission statement. Specifically, for Philippine PLCs, it indicates to management that there is value beyond regulatory compliance in creating and articulating their firms' mission statements. Philippine PLCs and other firms in emerging market likely confront the tensions of breadth and focus and market and society orientation in the articulation of their mission statement, as they jointly exploit market growth and fill institutional voids. A clear determination of who the firm's customer, be it on a component or stakeholder approach, is necessary. Further, as the firm works through the tensions, particularly on the stakeholders, it is vital to identify the salient stakeholders to help in balancing competing claims.

Limitations

This study is limited to a static, one-point-in-time, and strategic approach to mission statement. It focuses on for-profit (large) PLCs and explores a direct relationship between mission statement and financial performance.

A static, one-point-in-time approach loses the additional insight of seeing ‘how and why mission statement change over time in response to various environmental and strategy changes could provide further insights’ (David, Reference David1989: 97). Also, there may be possibilities of a lag in the relationship between a firm's mission statement and its performance (Bart & Baetz, Reference Bart and Baetz1998).

Further, by taking a strategic approach to mission statement, this study assumes a mission statement is associated with higher financial performance. Financial benefits are just one possible operationalization of mission statement success according to Desmidt, Prinzie, and Decramer (Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011). Under the component approach, a firm may, for example, use a mission statement to establish a primary purpose of quality or technology leadership, which places financial performance in a secondary role. Under the stakeholder approach, Harrison and Wicks (Reference Harrison and Wicks2013) point out that financial returns may be an incomplete and an oversimplification of the utilities received by various stakeholders. Mission statements are also relevant for nonpublic and nonprofit organizations that may have a different take on the stakeholder approach and where ‘financial benefit then is not the criterion of choice to operationalize mission statement effectiveness’ (Braun, Wesche, Frey, Weisweiler, & Peus, Reference Braun, Wesche, Frey, Weisweiler and Peus2012: 431).

Also, just looking at the direct relationship and ignoring the process of creating a mission statement excises a mission statement from its organizational fabric and may result in a loss of vital information (Desmidt, Prinzie, & Decramer, Reference Desmidt, Prinzie and Decramer2011). The value of a mission statement may not be in the final output but in the process of coming up with it (Bartkus, Glassman, & McAfee, Reference Bartkus, Glassman and McAfee2004).

All these points to opportunities for further research that may be longitudinal, focuses on the mission statement process, and uses of other measures of success. This allows to explore dynamic, as well as intermediate, behavioral outcomes, and nonfinancial measures, such as satisfaction with a mission statement, mission statement influences over behavior, and commitment to the mission (Bart, Bontis, & Taggar, Reference Bart, Bontis and Taggar2001).

Regina M. Lizares (http://vsb.upd.edu.ph/faculty/lizares) is an Associate Professor of the Cesar E.A. Virata School of Business, University of the Philippines, where she teaches undergraduate, master, and PhD-level courses. She is a core faculty for the courses on International Business, Strategy Management, Human Behavior in Organization, Organization Theory, Introduction to Business Management, General Management, and Industrial Organization. She graduated from the University of the Philippines with a PhD in Business Administration (2018), an MS in Management (2018) and a BS in Business Administration, Magna Cum Laude (1988). She also completed an MA in International Business and Economic Development, with Distinction (1995) as a Chevening scholar from the University of Reading (UK), and a Master in Business Administration, Bilingual Programme (1991) from IESE (Spain).