INTRODUCTION

Deforestation and degradation of natural forests continue to threaten the persistence of biodiversity and ecosystem services in tropical countries (Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Lee, Koh, Brook, Gardner, Barlow, Peres, Bradshaw, Laurance, Lovejoy and Sodhi2011; Vieilledent et al. Reference Vieilledent, Grinand and Vaudry2013; WWF 2014), even though forest conservation is economically beneficial (MEA 2003; TEEB Reference Kumar2010). In many cases, the benefits of forest conservation exceed its costs due to the value of biodiversity and the ecosystem services provided by forests. However, while the global community enjoys most of the benefits, local populations typically bear high opportunity costs (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Ferraro Reference Ferraro2002; Balmford & Whitten Reference Balmford and Whitten2003; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006).

Successful forest conservation depends on the creation of forest conservation incentives for local forest users. Changing the local cost–benefit relationship is especially important in states with poor economic development and weak governance. Otherwise, forest conservation projects and protected areas risk being ineffective due to the lack of enforcement capacity and compliance of local users (Mascia et al. Reference Mascia, Pallier, Krithivasan, Roshchanka, Burns, Mlotha, Murray and Peng2014). This long-known misfit in cost–benefit relations (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Ferraro Reference Ferraro2002; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006) prompted government organizations (GOs) and non-government organizations (NGOs) to design and implement numerous projects to allow local populations to profit from conservation. But continuing deforestation suggests that efforts to translate the values generated by forest preservation into real local benefits have so far not been successful (Balmford & Whitten Reference Balmford and Whitten2003; Hanson Reference Hanson2012; Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, Nicoll, Mbohoahy, Oleson, Ratsifandrihamanana, Ratsirarson, Rene, Virah-Sawmy, Zafindrasilivonona and Davies2013).

Madagascar is a prominent example of such unfortunate developments. Its many endemic species and the high deforestation rate qualify Madagascar as a global conservation priority (Myers et al. Reference Myers, Mittermeier, Mittermeier, da Fonseca and Kent2000; Goodman & Benstead Reference Goodman and Benstead2005; Ganzhorn et al. Reference Ganzhorn, Wilmé, Mercier and Scales2014). On the other hand, Madagascar ranks 155th of 187 states in the Human Development Index and serves as a prime example of a region in which a large share of the population depends heavily on the ecosystem services provided by their environment for survival and in which the risk of malnutrition is very high (Scales Reference Scales2014a; UNDP 2014; Welthungerhilfe 2014). Despite efforts by GOs and NGOs to conserve forests and improve the situation of the rural population, deforestation in Madagascar is proceeding at rates close to 1% per year, with regional highs above 2% per year (Harper et al. Reference Harper, Steininger, Tucker, Juhn and Hawkins2007; ONE et al. 2013; Brinkmann et al. Reference Brinkmann, Noromiarilanto, Ratovonamana and Buerkert2014; Zinner et al. Reference Zinner, Wygoda, Razafimanantsoa, Rasoloarison, Andrianandrasana, Ganzhorn and Torkler2014). The situation in Madagascar is thus exemplary of many biodiversity-rich developing countries striving to reconcile development and conservation objectives.

Here we review the cost–benefit relationships of forest protection and the impact of recent conservation projects and other activities on the local population in Madagascar. Our review is the first of this type for the biodiversity-rich island. We review the envisioned costs and benefits from forest protection of three cost-benefit analyses (CBAs) and contrast them with evidence (a) on the actual burdens of forest conservation for the local population and (b) on the actual local gains from forest conservation, generated mainly in the context of conservation projects. We go beyond the existing CBAs by collecting evidence on actually generated values for all cost and benefit types considered in the CBAs and assess the potentials and impediments for the realization of the different benefit types.

CBAs quantify the costs and benefits of a project with the aim of assessing whether the project is economically beneficial to society (i.e. has a positive net present value). The net present value of a project equals the difference between the present values of the (aggregated) benefits and (aggregated) costs, which are calculated by summing up discounted future costs and benefits. A high discount rate indicates that future costs and benefits are given a low value compared to present ones. In order to be methodologically sound, all benefits and costs of a project need to be included and monetized. If no market prices exist, benefits or costs have to be estimated with appropriate methods, such as contingent valuation (willingness-to-pay or willingness-to-accept studies). In CBAs, the potential benefits of alternative use of an area are included as opportunity costs. The opportunity costs of using a resource for a particular purpose are defined as the foregone benefits of being unable to use this resource for the highest-valued alternative purposes (e.g. Hanley & Barbier Reference Hanley and Barbier2009; Boardman et al. Reference Boardman, Greenberg, Vining and Weiner2010).

METHODS

The review is based on literature sources in English and French on the economic dimensions of forest use activities and conservation projects in Madagascar. In a first step, the Web of Science was searched for papers with the keywords ‘forest conservation’, ‘Madagascar’, ‘costs’, ‘benefits’ and terms defining different types of costs and benefits (e.g. ‘charcoal’, ‘silk’ and ‘medicinal plants’). Keywords were used in different combinations mainly connected by ‘and’ for searching ‘topics’ in all years. We found that many of the papers identified through this search were not relevant to our analysis. Therefore, in a second step we manually selected those sources assessing the different types of costs or benefits either qualitatively or quantitatively. Open web-based searches and experts on forest conservation in Madagascar helped with access to books, project reports and other grey literature sources.

POLITICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF MADAGASCAR'S CONSERVATION POLICY

Policies to protect Madagascar's forest date back to the pre-colonial period in the late 19th century. They have seen rapid expansion since the late 1980s when Madagascar received an enormous influx of development funds, including support for integrated conservation and development projects (ICDPs), community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) and payments for ecosystem services (PES) (Mercier Reference Mercier2012; Scales Reference Scales2014a).

Since 1996, the rights to manage natural resources have been transferred to local populations under the regulations Gestion Locale Sécurisée (GELOSE; transfer of property rights to local communities). It was expected that community-based management would solve the problem of open access to forest resources and resolve conflicts between traditional management rights and state policies. Moreover, funds for the basic communities (in Malagasy: Vondron'Olona Ifotony) should be generated through payments from the local population (Hockley & Andriamarovololona Reference Hockley and Andriamarovololona2007; Pollini & Lassoie Reference Pollini and Lassoie2011). However, the actual implementation was criticized for assigning a strong role to external NGOs and external goals and neglecting the interests of local communities. In consequence, the large-scale implementation of CBNRM under the GELOSE regulations still suffers from insufficient incentives for local households to preserve the resources under their management. Thus, while CBNRM or some other form of community participation in conservation is important, actual benefit generation requires additional efforts (Hockley & Andriamarovololona Reference Hockley and Andriamarovololona2007; Fritz-Vietta et al. Reference Fritz-Vietta, Röttger and Stoll-Kleemann2009). The latest phase of government environmental policies, initiated with the ‘Durban vision’ of President Ravalomanana in 2003, aimed to triple the area of protected zones (Corson Reference Corson and Scales2014). However, the success of conservation projects has been mixed at best, and deforestation still has not been stopped (Sayer Reference Sayer2009; Freudenberger Reference Freudenberger2010; Brinkmann et al. Reference Brinkmann, Noromiarilanto, Ratovonamana and Buerkert2014; Corson Reference Corson and Scales2014; Zinner et al. Reference Zinner, Wygoda, Razafimanantsoa, Rasoloarison, Andrianandrasana, Ganzhorn and Torkler2014).

CBA OF FOREST PROTECTION IN MADAGASCAR

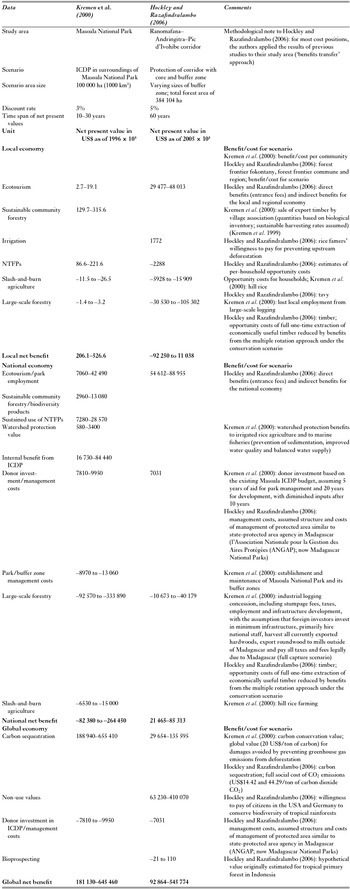

In Madagascar, CBAs for an ICDP close to Masoala National Park (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000) and for the protection of the Ranomafana-Andringitra-Pic d'Ivohibe corridor (Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006) identified costs and benefits at the local, national and global levels. Both studies found positive net benefits for the establishment of the forest protection projects, but also significant local and national costs compared to high benefits for globally valued ecosystem services (Table 1). In these scenarios, permission for timber extraction is crucial and benefits from this activity must be captured by local communities (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006).

Table 1 Two cost–benefit analyses for forest conservation in Madagascar (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006). ICDP = integrated conservation and development project; NTFP = non-timber forest product.

A third CBA assessed the value of Madagascar's network of protected areas and also estimated a positive net present value of conservation efforts (Table 2) (Carret & Loyer Reference Carret and Loyer2004). Thus, in all three CBAs, the benefits from forest products, biodiversity conservation, watershed protection and ecotourism outweigh the costs of forest protection.

Table 2 Cost–benefit analysis of the system of protected areas in Madagascar based on Carret and Loyer (Reference Carret and Loyer2004).

BURDENS OF FOREST CONSERVATION FOR THE LOCAL POPULATION

Slash-and-burn agriculture

Slash-and-burn agriculture (tavy) is the predominant system of agriculture practised in the eastern rainforest regions for rice cultivation and constitutes the main cause of deforestation and biodiversity loss in Madagascar (Minten Reference Minten2003; Styger et al. Reference Styger, Rakotondramasy, Pfeffer, Fernandes and Bates2007; Scales Reference Scales2014a). To assess the cost of abandoning slash-and-burn agriculture, estimations have used household models and considered a switch to income sources in order to replace deforestation or forest use activities (Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Sharma and Munasinghe1995; Shyamsundar & Kramer Reference Shyamsundar and Kramer1997; Ferraro Reference Ferraro2002; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006). Others assess the willingness to accept compensation for abandoning slash-and-burn agriculture or the use of non-timber forest products (NTFPs) (Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Sharma and Munasinghe1995; Minten Reference Minten2003). The opportunity costs per household are similar at different sites and probably represent the lower margin of opportunity costs since aspects such as health costs, the value of medicinal plants and social and cultural aspects were not considered (Table 3). The costs are low by western standards, but represent significant shares of the local households’ total income (Shyamsundar & Kramer Reference Shyamsundar and Kramer1997; Ferraro Reference Ferraro2002). Opportunity costs vary subject to whether the use of NTFP is allowed or not (Table 3) and can be higher for abandoning the use of NTFPs than for abandoning slash-and-burn agriculture and differ between household types within and between villages (Minten Reference Minten2003).

Table 3 Opportunity costs of abandoning non-sustainable forest use on the local level in Madagascar. NTFP = non-timber forest product.

Logging of high-value timber

Non-sustainable commercial timber extraction is an important cause of deforestation in north-eastern Madagascar. Although logging targets few species, summarized under the name ‘rosewood’ (Dalbergia spp. and Diospyros spp.), the damage to the whole forest is considerable (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Lopez and Rahaga2009; Burivalova et al. Reference Burivalova, Bauert, Hassold, Fatroandrianjafinonjasolomiovazo and Koh2015). Madagascar rosewood is mainly exported to China (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Lopez and Rahaga2009; Randriamalala & Liu Reference Randriamalala and Liu2010). An estimated 52 000 tonnes were logged in 2009 in north-eastern Madagascar, of which an estimated 36 700 tonnes were shipped to China for a total export sale price estimated at US$220 million (Randriamalala & Liu Reference Randriamalala and Liu2010). Most of the profits from rosewood trafficking are reaped by the exporters, while the state collects only negligibly in the form of taxes and fines, and local communities profit only marginally. Taking into account the area impacted during logging, a rosewood revenue of US$31–76 per hectare is achieved (based on Randriamalala & Liu Reference Randriamalala and Liu2010). Rosewood trafficking has increased significantly since the 2009 coup as a result of political instability and rising corruption and has brought some species near to extinction (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Brown, Morikawa, Labat and Yoder2010). In the two CBAs summarized earlier, the foregone benefits from timber extraction represent the most important opportunity costs on the regional and national levels (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006). Both studies assumed that logging companies respect Malagasy laws and pay all taxes legally that are due from logging. In a more realistic approach, Kremen et al. (Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000) calculated a scenario in which the state captures a third of the logging taxes. Even in this scenario, timber extraction still remains the most important factor in the opportunity costs on the national level. However, this remains speculative.

Charcoal production

Deforestation through charcoal production is high near access roads to urban centres (Minten et al. Reference Minten, Sander and Stifel2013) and in the dry spiny forest region in the southwest of Madagascar (Sussman et al. Reference Sussman, Green and Sussman1994; WWF Global 2010). The high charcoal demand in urban centres led to supply problems and longer transport routes, which induced the establishment of eucalyptus plantations (Gade & Perkins-Belgram Reference Gade and Perkins-Belgram1986). The charcoal sector provides income opportunities to the rural poor through production, petty retail or casual work (Minten et al. Reference Minten, Sander and Stifel2013). Especially in the southwest, it also offers poor rural households income opportunities during drought years (WWF Global 2010; Neudert et al. Reference Neudert, Andriamparany, Rakotoarisoa and Götter2015). There, the situation is aggravated because charcoal cannot be produced economically with tree plantations as trees grow very slowly under the dry climate of the south-west. Despite the regional importance of charcoal production, it was not included in any CBA.

GAINS FOR LOCAL POPULATIONS FROM FOREST CONSERVATION

Benefit generation

Non-timber forest products

The rural Malagasy population uses a wide range of NTFPs. There are few Strict Nature Reserves (IUCN Category I) in Madagascar where extraction of NTFPs is prohibited (Bemaraha, Tsaratananana, Betampona and Zahamena). The majority of protected areas fall into IUCN Category II or lower, which allow utilization of forest products to some extent.

Fruits

In eastern Madagascar, about 150 plant species with edible fruits have been recorded growing in forests or on agricultural land. Wild fruits are consumed directly or sold to raise income. Commercialization of wild fruits is mainly undertaken by poorer households living closest to forests. However, the market for wild fruits remains unorganized and prices are low (Styger et al. Reference Styger, Rakotoarimanana, Rabevohitra and Fernandes1999; Schatz Reference Schatz2001; Mananjo et al. Reference Mananjo, Rejo-Fienena, Tostain, Tostain and Rejo-Fienena2010).

Yams

About 40 species of yam occur in Madagascar, most of which are endemic (Jeannoda et al. Reference Jeannoda, Razanamparany, Rajaonah, Monneuse, Hladik and Hladik2007). While in the dry west (Menabe and Mikea) the diversity of wild, endemic species is especially high, introduced and cultivated yams are abundant in shifting cultivation areas in the humid east (Jeannoda et al. Reference Jeannoda, Razanamparany, Rajaonah, Monneuse, Hladik and Hladik2007). All yam species are important food sources during the lean season and occasionally contribute to cash income, especially among poorer households (Jeannoda et al. Reference Jeannoda, Razanamparany, Rajaonah, Monneuse, Hladik and Hladik2007; Cheban et al. Reference Cheban, Rejo-Flenens and Tostain2009; Andriamparany et al. Reference Andriamparany, Brinkmann, Wiehle, Jeannoda and Buerkert2015). In south-western Madagascar, sales of yams can provide weekly revenues of about US$1.9 to collectors during the harvesting period. This amount does not capture the total value of yams, as intermediate dealers buy from collectors and sell to consumers at much higher prices (Cheban et al. Reference Cheban, Rejo-Flenens and Tostain2009).

Bushmeat

Bushmeat, including wild mammals and birds, provides a complementary source of protein in addition to domestic animals. While some species are endangered and strictly protected or considered taboo (fady), others (e.g. fruit bats and tenrecs) can be hunted legally at certain times of the year (Randrianandrianina et al. Reference Randrianandrianina, Racey and Jenkins2010; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Fernald, Brashares, Rasolofoniaina and Kremen2011). Some types of bushmeat represent important sources of income for the rural poor (e.g. in south-eastern Madagascar where hunters sold more lemurs than they consumed) (Randrianandrianina et al. Reference Randrianandrianina, Racey and Jenkins2010). Based on data from wildlife sales, the value of wildlife represented 57% of the annual household cash income in local communities in the Makira Natural Park and Masoala National Park. This is equivalent to an economic return of US$0.42 per hectare and year in the harvested areas (Golden et al. Reference Golden, Bonds, Brashares, Rasolofoniaina and Kremen2014). In south-western Madagascar, bushmeat hunting is a secondary activity and probably has an important function as a safety net (Gardner & Davies Reference Gardner and Davies2014). Although sustainable wildlife hunting can potentially generate long-term benefits for the local population, hunting has increased and is a major conservation concern (Barrett et al. Reference Barrett, Brown, Morikawa, Labat and Yoder2010; Randrianandrianina et al. Reference Randrianandrianina, Racey and Jenkins2010). In addition, many of Madagascar's unique species achieve very high prices on the international pet market. Due to the mostly illegal nature of this market, the opportunity costs are difficult to estimate but are likely to be substantial (Raselimanana Reference Raselimanana, Goodman and Benstead2003; Ganzhorn et al. Reference Ganzhorn, Manjoazy, Paeplow, Randrianavelona, Razafimanahaka, Ronto, Vogt, Wätzold and Walker2015).

Medicinal plants and genetic diversity

Medicinal plants play a central role in traditional medicine, but are also traded on international markets (Schippmann et al. Reference Schippmann, Leaman and Cunningham2002). In Madagascar, diverse plant species are collected mostly from the wild by rural households and traditional healers. For most medicinal plants, the exchange value associated with single plants is uncertain (Méral et al. Reference Méral, Raharinirina, Andriamahefazafy and Andrianambinina2006), but they represent a low-cost alternative to western medicine. For the Makira protected area, Golden et al. (Reference Golden, Rasolofoniaina, Anjaranirina, Nicolas, Ravaoliny and Kremen2012) estimated an average of 82 treatments per year with botanical ethnomedicine from the forest having an equivalent value of US$30.24−44.30 per household and year.

An important exported medicinal plant growing in forests is the bark of Prunus africana, which can generate more than 30% of a village's revenue (Péchard et al. Reference Péchard, Antona, Aubert and Babin2005). The local markets for medicinal plants are segmented and prices paid to collectors for unprocessed material are low; therefore, the rural population receives only an insignificant share of the consumer price (Péchard et al. Reference Péchard, Antona, Aubert and Babin2005; Méral et al. Reference Méral, Raharinirina, Andriamahefazafy and Andrianambinina2006). P. africana and other medicinal resources in Madagascar are increasingly threatened by unsustainable collection and deforestation (Stewart Reference Stewart2003).

Silk

Madagascar has a long tradition of silk production and there are a number of wild silk-producing species, especially in the highland Tapia forests and the western and northern provinces (Moat & Smith Reference Moat and Smith2007; CITE/Boss Corporation 2009). Silk production is often a secondary income source for farmers (ACI 2008; Hance Reference Hance2012), but it can contribute up to 40−60% of total household income (CITE/Boss Corporation 2009). The domestic silk market is growing with a high demand for traditional silk scarves among the domestic population and tourists (ACI 2008). Numerous projects aim to enhance silk production and marketing in order to generate direct benefits for rural producers from standing forests (Razafimanantosoa et al. Reference Razafimanantosoa, Ravoahangimalala and Craig2006; CITE/Boss Corporation 2009; Hance Reference Hance2012). However, policy failure and uncoordinated production, processing and trade limit growth and investment (ACI 2008; Hance Reference Hance2012). ACI (2008) estimated a possible output growth from 57 tonnes of silk cocoons per year to 174 tonnes per year over the next 10 years. This would generate an output value of US$3.8 million and multiplier effects on the regional and national levels of US$5.5 million.

Sustainable timber extraction

Kremen et al. (Reference Kremen, Razafimahatratra, Guillery, Rakotomalala, Weiss and Ratsisompatrarivo1999, Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000) calculated greater benefits in sustainable use areas from sustainable timber extraction, where a certified management system of high-value timber in cooperation with certified timber companies would translate into an annual benefit of US$130 per household. However, it is unclear whether local communities are able to capture these benefits (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Razafimahatratra, Guillery, Rakotomalala, Weiss and Ratsisompatrarivo1999, Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000). Apart from uncertainties on how benefits could be shared, the definition and calculation of ‘sustainability’, and thus the possible revenue to be obtained, is still a matter of debate (Plugge et al. Reference Plugge, Baldauf and Koehl2013). Thus, the benefits outlined by Kremen et al. (Reference Kremen, Razafimahatratra, Guillery, Rakotomalala, Weiss and Ratsisompatrarivo1999, Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000) should be taken as proxies rather than concrete values.

In principle, sustainable use of forest resources, including the use of timber, is a key goal of the devolution of management under the GELOSE law. However, successful transfer of management rights and improvements in forest conditions were achieved in very few cases (McConnell & Sweeney Reference McConnell and Sweeney2005; Raik & Decker Reference Raik and Decker2007). In particular, the economic challenges encountered by households in reducing slash-and-burn agriculture were rarely addressed. Yet without the creation of viable income alternatives and reinforcement of the existing law, forest management is unlikely to be sustained (Cuvelier Reference Cuvelier, Ganzhorn and Sorg1996; Raik & Decker Reference Raik and Decker2007; Urech et al. Reference Urech, Sorg and Felber2013).

Ecotourism

Madagascar's biodiversity is an important attraction for international tourists, with ecotourism making up the largest segment of the sector (Christie & Crompton Reference Christie and Crompton2003). Tourism accounted for 6.4% of Madagascar's GDP in 2006 (Lapeyre et al. Reference Lapeyre, Andrianambinina, Requier-Desjardins and Méral2007), with a growth rate of over 200% between 1990 and 2000 (Christ et al. Reference Christ, Hillel, Matus and Sweeting2003; de Groot & Ramakrishnan Reference de Groot, Ramakrishnan, Hassan, Scholes and Ash2005). In CBAs for forest protection, ecotourism is seen as a major potential source of income by capturing tourists’ willingness to pay for visiting natural sites (Carret & Loyer Reference Carret and Loyer2004; Ormsby & Mannle Reference Ormsby and Mannle2006). While ecotourism has become a major source of income in some regions (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Andriamihaja, King, Guerriero, Hubbard, Russon and Wallis2014), ecotourism is concentrated in very few tourist hotspots; even there, the ecotourism benefits fail to compensate the costs of forest protection at local and regional levels (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000; Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006).

Revenues to local communities and Madagascar National Parks administration are being generated through direct marketing such as entrance fees, employment of local residents and tourist expenditures (Chaboud et al. Reference Chaboud, Méral and Andrianambinina2004; Dolch Reference Dolch and Goodman2008; Wollenberg et al. Reference Wollenberg, Jenkins, Randrianavelona, Rampilamanana, Ralisata, Ramanandraibe, Ravoahangimalala and Vences2011; Sarrasin Reference Sarrasin2013). People benefitting materially from Masoala National Park had a more positive opinion of the park and were more willing to engage in its protection (Ormsby & Mannle Reference Ormsby and Mannle2006).

Policy mechanisms for paying locals for global benefits

Payments for ecosystem services

PES can be described as voluntary contractual arrangements between ‘buyers’ and ‘sellers’ for the delivery of an ecosystem service or the provision of biodiversity (Engel et al. Reference Engel, Pagiola and Wunder2008). PES compensate local land users (sellers) for the provision of ecosystem services and biodiversity related to forest conservation through payments by national or international beneficiaries (buyers). In recent years, PES have been promoted as means of achieving conservation goals (TEEB Reference Kumar2010).

Carbon sequestration

Carbon conservation values that are accruing at the global level outweigh all opportunity costs on local and national levels (Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Niles, Dalton, Daily, Ehrlich, Fay, Grewal and Guillery2000). Thus, selling carbon certificates could provide substantial incentives for conservation (Hockley & Razafindralambo Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006), although possible benefits vary widely between forest types (Plugge et al. Reference Plugge, Baldauf, Rakoto RatsimbaI, Rajoelison and Köhl2010). Nevertheless, Madagascar has emerged as one of the prime recipients of Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) and Clean Development Mechanism payments. Since 2008, 11 REDD+ projects have been implemented or are planned in Madagascar, predominantly by global conservation NGOs such as Conservation International, the Wildlife Conservation Society and the World Wide Fund for Nature (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2009). All REDD+ projects rely on CBNRM village associations for their implementation at the local level (Runeberg Reference Runeberg, Angelsen, Brockhaus, Sunderlin and Verchot2013). In addition, there are several other projects aiming at carbon storage in forests, but not under the umbrella of REDD (Ferguson Reference Ferguson2009).

However, the actual transfer of benefits from carbon sequestration is still limited to a few pilot areas. The most advanced REDD+ project in Madagascar is the Makira REDD+ project implemented by the Wildlife Conservation Society. Since 2008, the Makira Carbon Company has raised US$700 000 through the sale of carbon credits for project implementation. Nevertheless, further sale of carbon credits in that project did not take place until 2014 (Brimont & Bidaud Reference Brimont, Bidaud and Scales2014). Another example is the Mantadia project in the east of Madagascar implemented by Conservation International (Wendland et al. Reference Wendland, Honzak, Portela, Vitale, Rubinoff and Randrianarisoa2010). The Mantadia project is a voluntary agreement on carbon storage between the ‘sellers’ (Madagascar´s government) and the ‘buyers’ (the World Bank's BioCarbon Fund). Monetary benefits are paid directly to the CBNRM organization, financing local patrolling, community organization and sometimes development projects. But while the overwhelming share of grants is used for community organization (per diems, transport costs, equipment and partly ineffective local patrolling), only an insignificant share flows to those locals bearing the opportunity costs of forest conservation (Brimont & Bidaud Reference Brimont, Bidaud and Scales2014).

Reviewing five existing REDD+ projects, Demaze (Reference Demaze2014) criticizes the strong role of international donors and NGOs compared to the weak Malagasy state and low involvement of regional and local actors. Runeberg (Reference Runeberg, Angelsen, Brockhaus, Sunderlin and Verchot2013) reports on insufficient coordination between and within projects due to a lack of leadership and institutional weaknesses at the state level.

Watershed protection

PES for watershed services are rare due to their high transaction costs (Andriamahefazafy Reference Andriamahefazafy2010). A pilot scheme for the delivery of water services was instituted for the Antarambiby river basin providing water for the city of Fianarantsoa (c.170 000 inhabitants). Local organizations of upstream users agreed with the water supplier on reducing rice farming, refraining from using chemical fertilizers and other measures to enhance water delivery and quality. As compensation, 196 households received Madagascar Ariary (MGA) 289 million (c.US$107 840) for a period of 2 years during the pilot phase (Andriamahefazafy Reference Andriamahefazafy2010). This amounts to a payment of c.US$275 per household and year, although data on the distribution of payments are not available. A similar scheme was implemented in 2009/2010 in the north of Madagascar in the river catchment area of Sahamazava with a contract of MGA 209 million (c.US$77 988) for 4 years and 32 households (Andriamahefazafy Reference Andriamahefazafy2010), translating to c.US$609 per household per year.

Biodiversity

Madagascar's unique biodiversity has a high value for the global community (e.g. Kramer et al. Reference Kramer, Sharma and Munasinghe1995; Markova-Nenova & Wätzold Reference Markova-Nenova and Wätzold2014). In the CBA of Hockley and Razafindralambo (Reference Hockley and Razafindralambo2006), these values constitute the highest benefits for the international community.

In contrast to the large number of projects piloting the selling of carbon offsets, actual benefit transfers for non-use biodiversity values are rare in Madagascar. An incentive payment scheme of community competitions was implemented by the Durell Wildlife Conservation Trust in the Menabe region (Sommerville et al. Reference Sommerville, Jones, Rahajaharison and Milner-Gulland2010a). Awards are distributed based on the performance of CBNRM in biodiversity conservation. The project's annual rewards of c.US$8500 are distributed in kind to the communities. While the distribution of benefits-in-kind in the communities was perceived as generally fair, no incentive is provided for those bearing the highest opportunity costs. Rather, behavioural changes seem to be driven by the fear of being caught as a result of increased monitoring activities (Sommerville et al. Reference Sommerville, Jones, Rahajaharison and Milner-Gulland2010a, Reference Sommerville, Milner-Gulland, Rahajaharison and Jones2010b).

A similar reward structure with participatory biodiversity management and rewards for communities was set up in the south for the Tsitongambarika Forest by Birdlife International in cooperation with the NGO Asity. Financing comes from ‘biodiversity offsetting’ by Rio Tinto and Rio Tinto QIT Madagascar Minerals mining ilmenite in this region (Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Bishop and Anstee2011; Temple et al. Reference Temple, Anstee, Ekstrom, Pilgrim, Rabenantoandro, Ramanamanjato, Randriatafika and Vincelette2012; Birdlife International 2015).

Benefit sharing from genetic diversity benefits

The biodiversity in Madagascar's ecosystems has a high economic option value in terms of its potential for the discovery of genetic and biochemical products (bioprospecting) (Jeffery Reference Jeffery2002; Raharinirina Reference Raharinirina2009). The economic significance of genetic resources has prompted interest in these resources and stimulated their trade (Jeffery Reference Jeffery2002; Raharinirina Reference Raharinirina2009). In the 1990s, Madagascar began to focus on the exploitation of its genetic resources, participating in international bioprospecting programmes and collaborating with laboratories and pharmaceutical companies abroad. Policies guiding access to genetic resources in accordance with the Convention on Biological Diversity (United Nations Treaty Service reference: C.N.329.1996.TREATIES-2) exist in Madagascar and were the basis of bioprospecting contracts. Two contracts, one with the International Cooperative Biodiversity Group (ICBG) Zahamena and one with ICBG Ranomafana, have since been signed, aiming to integrate the discovery of medicinal plants into research, rural development and biodiversity conservation (Raharinirina Reference Raharinirina2009). While the ICBG Zahamena considered only benefits for research institutions in Madagascar, the local communities were also supposed to benefit directly under the ICBG Ranomafana. However, real benefit sharing with local households remained questionable as the main focus was on community development measures (Raharinirina Reference Raharinirina2009).

DISCUSSION

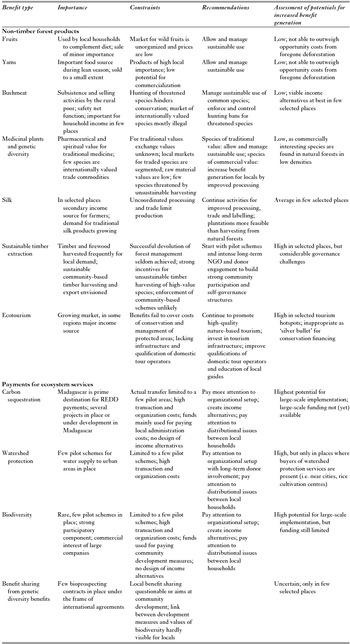

CBAs demonstrate large net benefits of forest conservation in Madagascar. While significant costs are incurred at local and national levels, the benefits of conservation accrue mainly to the global community, and policies still fail at enhancing and transferring benefits to local populations (Table 4). Similarly to the situation in Madagascar, this result may be found in many other biodiversity-rich developing countries striving to reconcile development and conservation objectives.

Table 4 Potential for increased benefit generation from ecosystem services for Madagascar's forests. NGO = non-governmental organization; REDD = Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation.

An important reason for this is that approaches to generating direct benefits often deliver less value than expected for rural communities. More specifically, short-term benefits for the local population that are higher than slash-and-burn agriculture are rare (Méral et al. Reference Méral, Raharinirina, Andriamahefazafy and Andrianambinina2006; Hance Reference Hance2012). Forest products such as fruits, honey, yams, bushmeat and medicinal plants are mainly used for consumption by poor rural households and often only serve as secondary sources of income, constituting a safety net when other income sources fail and delivering goods and services that are expensive to replace (Shackleton et al. Reference Shackleton, Shackleton and Shanley2011). Only silk production and bushmeat hunting provide employment and constitute the primary income source at selected locations (CITE/Boss Corporation 2009; Golden et al. Reference Golden, Bonds, Brashares, Rasolofoniaina and Kremen2014). If the sustainable management of NTFPs in forests is possible and does not contradict conservation goals, it seems appropriate to allow some degree of harvesting of NTFPs in forests and management zones of protected areas. Although the benefits are too small to outweigh the benefits of slash-and-burn agriculture, NTFPs support the livelihoods of local land users and thus might enhance acceptance of forest conservation.

Another reason for the failure of increased benefit generation for local people is that marketing opportunities for forest benefits are often insufficiently developed and, if they are developed, they often face problems of elite capture of benefits and governance failure on the national and regional levels (Ballet et al. Reference Ballet, Lopez and Rahaga2009). Complex institutional and structural challenges in marketing hinder increased benefit generation from ecotourism and sustainable timber extraction. In principle, ecotourism can constitute a viable alternative source of income for local households in some highly frequented tourist destinations (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Andriamihaja, King, Guerriero, Hubbard, Russon and Wallis2014). However, the inability of the local economy to capture a substantial share of these benefits due to a lack of skills and capital and existing power relations is a major problem. Similarly, sustainable timber extraction could potentially provide significant benefits to the local population, especially in the humid forests of Madagascar, where trees achieve higher growth rates than in dry forests (Cuvelier Reference Cuvelier, Ganzhorn and Sorg1996; Kremen et al. Reference Kremen, Razafimahatratra, Guillery, Rakotomalala, Weiss and Ratsisompatrarivo1999).

Institutional limitations in the local communities and governance failure at higher levels also limit benefit transfer mechanisms that, in principle, could bridge the gap between the high benefits on the global level and the local costs of conservation. Under weak governance conditions, intermediary institutions and the process of overcoming high transaction costs are crucial for benefit transfer mechanisms (Cahen-Fourot & Meral Reference Cahen-Fourot and Meral2011). International donor organizations focus more on community benefits than on direct compensation of households and so do not provide income alternatives for individual households. Moreover, where compensation is paid, due to a lack of information and education and local power relations, the beneficiaries may not be the affected households (Poudyal et al. Reference Poudyal, Ramamonjisoa, Hockley, Rakotonarivo, Gibbons, Mandimbiniaina, Rasoamanana and Jones2016). While it is possible to pay local households directly for not carrying out certain activities, the impact on the household in terms of livelihood security may be negative if those payments become unavailable sometime in the future (Kronenberg & Hubacek Reference Kronenberg and Hubacek2013). Similarly, the benefit transfer from the bioprospecting of genetic resources would require elaborate agreements between local representatives and international agents. However, recent examples have tended to go in the direction of decoupling bioprospecting and development projects financed by the compensation payments, thus not creating incentives for forest conservation at the local level (Neimark & Tilghman Reference Neimark, Tilghman and Scales2014).

There is no single panacea for overcoming failure to change cost–benefit relations for local land users, but rather several measures are needed. Unlike often in the past, the impact of conservation measures on local livelihoods should be addressed during the project planning phase (Scales Reference Scales2014b). Appropriate actions include enhancing alternative income sources, even outside natural forests. Especially when designing benefit transfer schemes, greater emphasis has to be placed on developing income alternatives for the local population.

In line with Hanson (Reference Hanson2012) and Scales (Reference Scales2014b), we recommend extensive communication between locals and conservationists to avoid misconceptions about local realities and insufficient local backing of initiatives. Conservation projects need to build on a detailed understanding of local land use systems, motivations to preserve resources and social relations inside local communities (Marie et al. Reference Marie, Sibelet, Dulcire, Rafalimaro, Danthu and Carriere2009; Poudyal et al. Reference Poudyal, Ramamonjisoa, Hockley, Rakotonarivo, Gibbons, Mandimbiniaina, Rasoamanana and Jones2016). They also need to consider cultural differences, especially in approaches to communication, and local power relations (Scales Reference Scales2014b).

To set up viable forest use schemes (e.g. for sustainable timber harvesting or ecotourism), a number of preconditions regarding appropriate governance structures at local, regional and national levels need to be addressed. This is challenging, especially for local communities (Hajjar et al. Reference Hajjar, McGrath, Kozak and Innes2011). Project periods of a few years are mostly insufficient for building organizational and social capacity within local societies for managing CBNRM initiatives independently (Urech et al. Reference Urech, Sorg and Felber2013). This often contradicts the planning horizons of donors and international NGOs aiming to achieve measurable success, mostly within 3 years. Thus, in striving to achieve milestones and indicators of project success on paper, the needs and concerns of local people are often of secondary concern. Moreover, long-term engagement of field-based personnel to build trust with locals, gain knowledge on local realities and facilitate participatory processes is often lacking. Thus, also on the side of donor projects and NGOs, important structural preconditions for working closely with the local population need to be improved (Urech et al. 2015).

Recommendations to establish participatory processes that strongly involve the local population (Hanson Reference Hanson2012; Scales Reference Scales2014b) also call for more interdisciplinary cooperation in the design and execution of projects, and especially the involvement of social scientists for a thorough understanding of local land use, motivations and cost–benefit relations. Longer project durations with adequate funding of field staff seem to be crucial in this regard. Thus, small pilot schemes with long-term donor engagement, a focus on people's livelihoods and participatory processes seem the most appropriate steps forward on the long path to achieving lasting success in forest conservation in Madagascar and elsewhere.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The study was carried out under the ‘Accord de Collaboration’ between Madagascar National Parks and the Universities of Antananarivo, Hamburg and Cottbus. The authors are grateful to the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the SuLaMa project team for assistance in collecting the literature and for supporting our work. The comments of two anonymous reviewers helped us to improve the manuscript significantly.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

The study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) as part of a project on sustainable land management of the Mahafaly Plateau (SuLaMa; grant number 01LL0914G).