Introduction

The transition from work to retirement is an important event in later life. The way individuals adapt to retirement has been a focus of interest for researchers in various scientific disciplines, such as epidemiology, psychology and sociology. The nature of retirement has changed enormously over the past few decades. Until 1960, retirement was generally considered a ‘crisis’ event, creating a challenge to personal wellbeing (Van Solinge and Henkens, Reference Van Solinge and Henkens2008). Nowadays, retirement is commonly seen as a new phase of life which offers opportunities for the development of new identities, roles and lifestyles (Mein et al., Reference Mein, Martikainen, Hemingway, Stansfeld and Marmot2003; Wang, Reference Wang2007). It is no longer associated with a conclusion (limited social roles, declining health, etc.), but can be described as the beginning of a third age of adulthood (Freedman, Reference Freedman1999).

This change in the nature of retirement, due in part to a continuous increase in life expectancy, the better health status of the retired, and their willingness to remain active in family and community roles, has increased the academic interest in the nature of retirement transition and how people live in retirement (Price and Nesteruk, Reference Price and Nesteruk2010). Representing a border between the middle age before retirement and a new stage of life (Ekerdt, Reference Ekerdt2010), retirement is a significant event in the context of the stabilisation of general health and successive developments in later life (Henning et al., 2016). Understanding how people cope with the new challenges this stage presents could help us to comprehend how people can maintain wellbeing and health even at older ages (Henning et al., 2016).

However, investigations focused on the influence of the retirement transition on quality of life have arrived at mixed results, and few studies have focused specifically on women. Current knowledge about the issue is primarily focused on men or on gender comparison (Price and Joo, Reference Price and Joo2005). Women's careers are often marked by interruptions or part-time employment which are often not considered in the active ageing debate (Foster, Reference Foster2011; König, Reference König2017). Career interruptions, caused by the birth of children, often produce great differences between the work histories of men and women (Foster, Reference Foster2011). For these reasons, it could be important to study female retirement adaptation as a standalone phenomenon since the whole process of retirement could be a different experience for women, because of the differences in their attachment to and participation in the labour force. When men leave their jobs, they are exiting from a role that has typically dominated their adult years. On the contrary, women, who commonly experience greater discontinuity in their working life (Sorensen, Reference Sorensen1983; Clausen and Gilens, Reference Clausen and Gilens1990; Moen, Reference Moen, Binstock and George2001), may have a different attachment to the role of ‘worker’ and a different adaptation to retirement.

A further limitation of previous analyses in studying the relationship between the transition to retirement, subjective wellbeing and the characteristics of the work history is that the information on work or employment has often been limited to a specific time-point, such as the last employment before retirement, without taking into account the influence of the entire working lifecourse. This strategy conflicts with one of the key principles of the lifecourse perspective, which suggests the incorporation of individual events into the different life trajectories and the consideration of their length and development (Elder et al., Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003).

The main goal of this paper is to investigate the change in subjective wellbeing of European women before and after the retirement transition, using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). I am interested in understanding if a change in the quality of life exists, and how various pre-retirement working trajectories are associated with this change. Women's work status (full-time, part-time, inactivity and unemployment) will be observed during their entire lifecourse; then the career structure will be related to the variation in wellbeing associated with withdrawal from the paid labour market. At the methodological level, sequence analysis and panel analysis techniques will be implemented.

Theoretical framework

Retirement is an important event that represents the start of a new lifestage in which work is no longer dominant, new opportunities present themselves, and both positive and negative changes can happen. Individuals have to adjust to this life change and pursue psychological wellbeing in retirement (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge and Whitbourne2015). Furthermore, the retirement process itself is changing and it is transforming. In periods of high unemployment, in most Western countries older workers were frequently pushed into early retirement to enable younger workers to enter the labour market (Blossfeld et al., Reference Blossfeld, Buchholz and Hofäcker2006; Ebbinghaus, Reference Ebbinghaus2006) and to keep the workforce competitive and adaptable to economic transformation (Buchholz et al., Reference Buchholz, Rinklake, Schilling, Kurz, Schmelzer and Blossfeld2011). However, due to population ageing and the increasing financial burden of pensions, a reverse trend can be observed since the beginning of 2000 (Ebbinghaus and Hofäcker, Reference Ebbinghaus and Hofäcker2013; König, Reference König2017). That is, in recent years, many countries have had the goal of keeping older workers in the workforce by closing paths to early retirement (König, Reference König2017). On the other hand, the increase in longevity means that retirement is becoming more a mid-life transition rather than a transition to old age; and retiring people often acquire new roles, continue to take on other roles (e.g. friend or spouse) and develop new identities (Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2001).

Research on the effects of retirement on wellbeing has shown very mixed conclusions. Some studies indicate that retirement is basically good for individual physical and psychological health (Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1996; Isaksson and Johansson, Reference Isaksson and Johansson2000; Latif, Reference Latif2011), whereas the opposite effect has also been empirically supported (Richardson and Kilty, Reference Richardson and Kilty1991; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002). Yet again, there are studies suggesting that retirement has virtually no implications at all for post-retirement wellbeing (Crowley, Reference Crowley and Parnes1985; Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher, Robertson and Callinan2004; Luhmann et al., Reference Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid and Lucas2012).

Still, many studies on retirement adjustment rely on cross-sectional designs, comparing differences in quality of life between workers and retirees (e.g. Herzog et al., Reference Herzog, House and Morgan1991; Midanik et al., Reference Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa1995; Drentea, Reference Drentea2002). However, these kinds of data do not allow us to observe the intra-individual changes in wellbeing during the retirement transition (Wang, Reference Wang2007). It is therefore necessary to adopt a longitudinal design in studying individuals’ variation in wellbeing. Indeed, dynamic, longitudinal analyses can capture the process of moving from a job to retirement and can clarify the evolving consequences of this transition (Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2001).

The major theoretical perspectives that have been applied as frameworks to study this heterogeneity in retirement adjustment include role theory and continuity theory (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Henkens and van Solinge2011). Both theories reason about the function that social roles – both working and extra-working roles – play in defining the identity of the individual. Coming to different conclusions, both theories address the consequences that losing a role can have for a person's adaptation and wellbeing. These theories have often been integrated with a lifecourse approach, which allows us to study retirement as a transition inserted in a lifelong process and not as a result of an isolated time-point. All these perspectives could be seen as complementary rather than contradictory because they focus on different aspects of the retirement adaptation process (Van Solinge, Reference Van Solinge and Whitbourne2015).

Role theory

Role theory has been often used as a framework for understanding retirement adjustment and, in particular, post-retirement psychological wellbeing. This theory suggests that some socially and personally relevant roles are important to building self-identity (Moen et al., Reference Moen, Erickson and Dempster-McClain2000; Petters and Asuquo, Reference Petters and Asuquo2008). They can emerge through relationships with neighbours, through work activities, through the family and so on. Therefore, society is structured around various roles, which prescribe norms and expectations for both behaviours and attitudes (Richardson and Kilty, Reference Richardson and Kilty1991). Individual differences in adaptation to role changes can be understood by examining variations in different life transitions.

Since leaving the workforce requires a change of roles and activities, this approach can be applied to the retirement process as well. Therefore, retirement is seen as a transition that involves an expansion, redefinition and change of roles. Differences in post-retirement wellbeing can thus be attributed to an individual's ability to react to those changes.

The influence that the loss of role has on individual psychological wellbeing depends on the importance of that role during the lifecourse and the possibility of finding other satisfactory replacement roles (Carter and Cook, Reference Carter and Cook1995). In fact, insofar as a person is strongly committed to a particular role, feelings of self-esteem tend to be associated with the ability to perform that role effectively (Ashforth, Reference Ashforth2001).

Role theorists argue that the ‘rolelessness’ – or a bad adaptation to the new role of pensioner – can cause people to feel unhappy, anxious or depressed. This dynamic can lead to low levels of wellbeing in the post-retirement period (Riley and Riley, Reference Riley, Riley, Riley, Kahn and Foner1994), and life after retirement could be perceived as less satisfying than life before that transition. Indeed, researchers have found evidence that role loss is associated with decreased life satisfaction (Fry, Reference Fry1992) and it is linked to poorer adjustment (Van Solinge and Henkens, Reference Van Solinge and Henkens2008) as well as elevated levels of stress, depression and anxiety (Moen et al., Reference Moen, Dempster-McClain and Williams1992; Adams et al., Reference Adams, Prescher, Beehr and Lepisto2002). In general, work and employment relationships are considered an important source of identity, and their loss could have negative consequences on the wellbeing of the individual, also in accordance with the level of development of the other life spheres (Jæger and Holm, Reference Jæger and Holm2004).

Continuity theory

The continuity theory, proposed by Atchley (Reference Atchley1971), supports the idea that work is not as crucial for our self-concept and identity as role theory implies. We tend to form our identity from multiple sources and roles. Even though job-related roles and activities are lost, other sources for building one's identity remain, such as family and non-work-related social networks. Then, the coherence of life patterns over time is emphasised: there is a continuity of the self-identity in the retirement transition, and this continuity contributes to the adaptation of the individual to retirement (Atchley, Reference Atchley1999). Rather than focusing on retirement as a process of loss of role, continuity theorists describe it as an opportunity to maintain social relationships and life patterns. Therefore, this theory argues that there should be no significant decline in psychological wellbeing when people move from work to retirement unless they have difficulties in maintaining their general life patterns (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Henkens and van Solinge2011). The theoretical assumption of the continuity theory is that individuals are regularly guided by existing internal mental frameworks, which make them prone to maintaining similar patterns of behaviours across time (Atchley, Reference Atchley1999). Individuals tend to preserve their social roles, lifestyles and values even when they retire (Atchley, Reference Atchley1976, Reference Atchley and Kelly1993). In other words, the most common pattern of adjustment in retirement is maintaining the same lifestyle patterns developed prior to retirement (Wang, Reference Wang2007). Dealing with change, ageing adults select alternatives that are coherent with their prior social identities and activities, sustaining the sense of self.

Atchley (Reference Atchley1976) has also proposed a model for describing the retirement adjustment process. The first period of retirement – he claims – could be related to the so-called honeymoon, an increase in wellbeing, due to the experience of the new freedom. This period is then followed by what the author calls disenchantment, as people have to cope with daily life in retirement and new problems. Afterwards, retired people experience a sort of reorientation in which they need to learn how to cope with the realistic opportunities and demands of this stage of life. This period in turn leads to a phase of moderate stability. Finally, in the last stage, called termination, people could experience a loss of independence due to more marked age-related changes (Henning et al., 2016).

It should be noted that continuity theory does not exclude the existence of psychological stress caused by role exit and role transitions. Instead, it underlines that maintaining continuity is essential for retirees to preserve their psychological wellbeing. Therefore, individuals who maintain their lifestyle or activities through retirement or who view retirement as a realisation of a prior goal should not experience significant decline of psychological wellbeing during the retirement transition (Wang, Reference Wang2007). Moreover, retirement may offer the opportunity to spend more time in the roles of friend and family member (Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1994), which offer psychological continuity to retirees. These family and community roles may provide social relationships that enable social integration and increases wellbeing among adults (Reitzes and Mutran, Reference Reitzes and Mutran2004). The continuity theory further argues that retirement may offer relief from job pressure and performance expectations. This dynamic may improve psychological wellbeing. In short, continuity is so important in this perspective, since pre-retirement priorities and activities have more impact on later life than retirement itself.

Lifecourse theory

The lifecourse perspective (Elder, Reference GH1995)) ; Elder and Johnson, Reference Elder and Johnson2003) focuses on important points for the comprehension of post-retirement wellbeing: transitions and trajectories; contextual embeddedness; and the interdependence of spheres of life and timing of transitions (Szinovacz, Reference Szinovacz, Adams and Beehr2003). Transitions refer to changes of state over time (e.g. from employment to retirement) and trajectories refer to the development of life in relatively stable states (e.g. employment history). The concept of contextual embeddedness implies that the experience of life transitions and developmental trajectories depends on the specific circumstances in which the transition occurs (e.g. health, career trajectories, social network, etc.), and the principle of the interdependence of life spheres emphasises that experiences in one sphere of life (e.g. retirement life) influence, and are influenced by, experiences in other spheres of life (e.g. marital or working life) (Wang, Reference Wang2007).

A lifecourse perspective emphasises that retirement is one transition in the context of a lifetime of employment (Quick and Moen, Reference Quick and Moen1998), and stresses how individuals construct their life roles, including their careers, framed within the environment and other life domains. In general, the importance of earlier life experiences for explaining behaviour later in life is underlined (Settersten, Reference Settersten2003: 15–45).

In the existing literature, the influence of the working history on retirement adjustment has often been investigated through variables related to employment observed at a precise time-point (for instance, the job from which the individual retired; e.g. Atchley, Reference Atchley1982; Newman et al., Reference Newman, Sherman, Higgins and Szinovacz1982), providing only a snapshot of the work history itself (Quick and Moen, Reference Quick and Moen1998). Only a few studies have focused on the cumulative process over the lifecourse by examining lifecourse determinants of late-life outcomes (Ponomarenko, Reference Ponomarenko2016). However, they did not specifically focus on women's wellbeing after retirement. This gap in the literature is remarkable, given that work experiences accumulated over the lifecourse could be crucial in shaping the consequences of later-life transitions (Damman et al., Reference Damman, Henkens and Kalmijn2011; Bennett and Moehring, Reference Bennett and Moehring2015). Indeed, the lifecourse principle of agency within the structure (Settersten, Reference Settersten2003) postulates that older adults make choices and take actions within the opportunities and restrictions of their broader social worlds, influenced by various life domains and personal histories.

Previous labour market experiences vary to a great extent concerning, for instance, the number of years spent in employment, the occupational status achieved and experience of discontinuity in career paths (e.g. Wahrendorf et al., Reference Wahrendorf, Akinwale, Landy, Matthews and Blane2017). The accumulation of specific labour market experiences creates opportunities and limitations that drive older adults in their decisions and adaptation after retirement (Dingemans and Möhring, Reference Dingemans and Möhring2019). Career development is therefore seen as a lifelong process, in which other life roles are taken into account, allowing retirement decisions to be considered in the context of other relevant identities (spouse, grandparent, etc.) Hence, retirement is also seen as a life transition in an ongoing trajectory and the retirement experience as influenced by previous life events such as job-related variables and family-related variables (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Zhan, Liu and Shultz2008; Von Bonsdorff et al., Reference Von Bonsdorff, Shultz, Leskinen and Tansky2009).

The importance of women's employment history

As we have previously seen, the increase in women's labour force participation has contributed to the changing nature of retirement, as the number of women experiencing this later-life transition has increased and continues to do so (Slevin and Wingrove, Reference Slevin and Wingrove1995). Several researchers have shown that the retirement transition can no longer be perceived as a ‘male-only’ event (Price and Nesteruk, Reference Price and Nesteruk2010), and have highlighted the need to recognise the unique context in which women retire (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1993; Price, Reference Price1998; Richardson, Reference Richardson1999; Price and Nesteruk, Reference Price and Nesteruk2010). It has been also argued that traditional retirement models are unsuitable for women, who are more likely to have an uneven working live than men (Richardson, Reference Richardson1999; Simmons and Betschild, Reference Simmons and Betschild2001; Byles et al., Reference Byles, Tavener, Robinson, Parkinson, Smith, Stevenson, Leigh and Curryer2013). Indeed, there are several reasons for examining women's retirement separate from men's retirement (Price and Nesteruk, Reference Price and Nesteruk2010). These include the difference in how women experience retirement, the different way in which they combine work and family responsibilities, the financial instability of female retirees, and their greater longevity, which extends their retirement period compared to that of men (Price, Reference Price1998; Quick and Moen, Reference Quick and Moen1998; Price and Nesteruk, Reference Price and Nesteruk2010). Furthermore, the different occupational trajectories of women and men could influence their retirement process differently and this could affect an individual's orientation and satisfaction with life during retirement (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1996).

The literature about males’ retirement adjustment process highlights the importance of work for men's psychological wellbeing (Cinamon and Rich, Reference Cinamon and Rich2002), suggesting that men with long periods of non-employment have more depressive symptoms later on compared to men with continuous employment (Wahrendorf et al., Reference Wahrendorf, Dragano and Siegrist2013). It thus may be assumed that continuous employment promotes opportunities of meeting psychosocial and economic needs, while precarious and unstable careers may be accompanied by the recurrent experience of psychosocial stress, with adverse consequences for health and wellbeing (Chandola et al., Reference Chandola, Brunner and Marmot2006; Wahrendorf et al., Reference Wahrendorf, Dragano and Siegrist2013).

As for women, they are more likely to be care-givers for younger and older family members, and they often adapt their work behaviour to satisfy this responsibility (Hatch and Thompson, Reference Hatch, Thompson, Szinovacz, Ekerdt and Vinick1992; O'Rand et al., Reference O'Rand, Henretta, Krecker, Szinovacz, Ekerdt and Vinick1992; Pienta, Reference Pienta1999). These discontinuities in women's labour force participation lead to some negative consequences, such as having fewer opportunities to develop skills, increase knowledge or move up the organisational hierarchy. As a result, women may be less likely to receive promotions, accumulate pension credits or be in jobs with the most remunerated pension plans (Quick and Moen, Reference Quick and Moen1998). Several of these consequences could have an impact on retirement adjustment.

Two main arguments can be found in the literature regarding the role of gender in the retirement adjustment process (Damman et al., Reference Damman, Henkens and Kalmijn2015). On the one hand, women might have fewer difficulties adjusting to the loss of the social dimensions of work than men, as that they have more experience in terms of role transitions and career breaks, and may be more prone to perceive the family role as their main role (Damman et al., Reference Damman, Henkens and Kalmijn2015). Women are more likely to decrease their engagement in the labour market or even leave it when they have children. Consequently, having already taken advantage of alternative roles, the transition to retirement may be easier because they are often less attached to the labour market. Alternative roles should moderate the negative influence of retirement on the subjective wellbeing dimension (Ryser and Wernli, Reference Ryser and Wernli2017). On the other hand, it can be assumed that women face financial difficulties when they leave the job role, as they may be economically vulnerable due to their interrupted working careers or low-paid occupations (Damman et al., Reference Damman, Henkens and Kalmijn2015). In this regard, there is evidence that females have more negative attitudes towards retirement than males do, and that retirement is more likely to be linked with greater loneliness and depression for females than for males (Van Solinge and Henkens, Reference Van Solinge and Henkens2005; Fadila and Alam, Reference Fadila and Alam2016).

To conclude: since working careers, developed and combined with family histories, have important consequences for women's later-life characteristics (e.g. Pienta et al., Reference Pienta, Burr and Mutchler1994), the entire employment history could be considered to be an important factor in explaining the effect of the retirement transition on subjective wellbeing. More specifically, working history is interconnected with family responsibilities and, as such, it becomes a fundamental factor influencing the attachment to the labour market and to the role of ‘worker’.

Research questions

Despite the wealth of research investigating the relationship between life events and subjective wellbeing, there remains a limited understanding regarding the consequences of retirement on subjective wellbeing (Horner, Reference Horner2014) and its relationship with working lifecourses. Previous studies have often relied on repeated cross-sectional data that cover only a time-point in women's lives, even though work and care-giving roles vary over time (Moen and Chermack, Reference Moen and Chermack2005). Moreover, relatively little research has focused specifically on the relationship between women's working history and their subjective wellbeing – especially in the context of retirement transition.

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies show very mixed results regarding this theme. In fact, on the one hand, we have evidence that supports an increase in wellbeing after retirement (e.g. Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1996; Isaksson and Johansson, Reference Isaksson and Johansson2000; Latif, Reference Latif2011; Wetzel et al., Reference Wetzel, Huxhold and Tesch-Römer2016; Ponomarenko et al., Reference Ponomarenko, Leist and Chauvel2019). Several previous studies have shown that retirement may lead to a positive overall experience by offering opportunities for role enrichment (Wang, Reference Wang2007), leisure (Pinquart and Schindler, Reference Pinquart and Schindler2009) and civic engagement (Kaskie et al., Reference Kaskie, Imhof, Cavanaugh and Culp2008). These are all factors that have been shown to be positively linked to levels of wellbeing (Hershey and Henkens, Reference Hershey and Henkens2014).

On the other hand, some results go in the opposite direction, pointing to negative effects of the retirement transition (e.g. Richardson and Kilty, Reference Richardson and Kilty1991; Dave et al., Reference Dave, Rashad and Spasojevic2008). For new retirees, the experience of encountering substantial life changes could lead to a decreased sense of self-esteem (Ashforth, Reference Ashforth2001), anxiety and depression, and to a lower general level of subjective wellbeing (Hershey and Henkens, Reference Hershey and Henkens2014). There are also studies that find no effects (or continuity) of retirement transition on wellbeing (e.g. Crowley, Reference Crowley and Parnes1985; Mayring, Reference Mayring2000; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002; Warr et al., Reference Warr, Butcher, Robertson and Callinan2004; Szinovacz and Davey, Reference Szinovacz and Davey2006; Luhmann et al., Reference Luhmann, Hofmann, Eid and Lucas2012) and studies that find beneficial effects of retirement in the short term, followed by a long-term decline in wellbeing (Horner, Reference Horner2014), and that also point to differences relating to education and social status (Wetzel et al., Reference Wetzel, Huxhold and Tesch-Römer2016). Finally, there are studies that link the characteristics of working lifecourse with the retirement effects on wellbeing that have found that persons who have been involuntarily unemployed experience a significant increase in wellbeing after retirement (e.g. Hetschko et al., Reference Hetschko, Knabe and Schöb2014; Ponomarenko et al., Reference Ponomarenko, Leist and Chauvel2019), whereas economically inactive persons do not show the same increase (Ponomarenko et al., Reference Ponomarenko, Leist and Chauvel2019).

Due to the inconsistency of the results obtained by the existing literature and the lack of a solid theoretical framework regarding the association between women's working history and changes in psychological wellbeing through retirement, I find it very difficult to formulate verifiable hypotheses. Therefore, this research has an explorative intention and seeks to integrate the two main theories on retirement adaptation – role and continuity theory – with a lifecourse approach. I consider the entire working lifecourse of European women (from 20 to 50 years of age) and examine (a) whether the transition to retirement affects female subjective wellbeing and (b) whether a possible change in subjective wellbeing differs according to the structure of the working career.

Data and methods

Data

I use data from SHARE which is a multi-disciplinary and cross-national panel database of micro data on health, socio-economic status, and social and family networks of individuals aged 50 or older. Specifically, for the sequence analysis, I use the third and seventh waves, SHARELIFE, which were collected in 2008/2009 and in 2017. SHARELIFE provides detailed retrospective information about individual work–family trajectories from early adulthood until retirement. For the regression analysis and the sample selection I used the regular waves of the survey (Waves 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6) and the regular part of Wave 7. Indeed, Wave 7 contains the retrospective questionnaire for all respondents who did not participate in Wave 3 (first SHARELIFE questionnaire), as well as a panel questionnaire for all respondents who had already answered the first SHARELIFE interview and for the new respondents entering the survey. Brugiavini et al. (Reference Brugiavini, Orso, Genie, Naci and Pasini2019) transformed the employment history variables (combining Waves 3 and 7) into a long data format, the Job Episodes Panel, which includes all relevant information on employment history.

Sample selection

Sequence analysis and regression models have been applied to the same sample of individuals, which I selected as the population of interest in this study. I selected women who were working or were unemployed the first time they were observed in the panel (I therefore excluded women who had already retired or who were permanently sick or disabled) and who made the transition to retirement during the observation period. When constructing the sample, the observations reporting more than one retirement transition or returning to the labour market after retirement were censored (right-censoring). Indeed, the aim of the paper is to focus on the first retirement transition. Moreover, I selected only individuals with no missing information on the variables used in the models and I excluded respondents with fewer than five recorded years in the labour market. In fact, persons who were inactive during most of their life are often excluded from the population of interest because the notion of retirement presupposes prior work (Radl, Reference Radl2014). Since SHARELIFE does not provide current information but only retrospective events, the sample is constructed by, first, identifying the population of interest in the regular panel waves. Then, information about employment and family history is added to this sample. The final sample is composed of 2,877 respondents (with no missing information on any the variables used) from 11 European countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland).

Methods

The empirical analyses are developed in two steps: in the first part, I performed sequence analysis to construct the individual working sequences and to explore the existence of similar patterns of career. In the second part, I related the career clusters with the variation in wellbeing before and after the retirement transition, running different fixed effects regression models on the different sub-samples defined by each specific career cluster. In a first step, I estimated a fixed effects regression model including only the main independent variable, which accounts for the years before and after retirement, to assess how the association between retirement transition and life satisfaction varies across the different clusters/sub-samples, as defined by their working trajectories. I aggregate the independent variable in five categories (two or more years before retirement; one year before; retirement year; one year retired; two or more years retired) and the analysis is divided by career trajectory. In a second step, I introduced the relevant covariates into the models.

Sequence analysis

The use of sequence analysis to study lifecourse has been earning growing attention; it has been widely recognised as a valuable toolbox for investigating life trajectories (Abbott and Hrycak, Reference Abbott and Hrycak1990; Abbott and Tsay, Reference Abbott and Tsay2000; Billari and Piccarreta, Reference Billari and Piccarreta2005). Even if this method is mostly explorative, it makes it possible to trace lifecourses entirely, investigating dynamic processes that are difficult to understand with other methods in lifecourse research (like event history analysis) (Ponomarenko, Reference Ponomarenko2016).

Indeed, sequence analysis takes into account the whole career and makes it possible to treat data in a holistic way. Moreover, it permits a reduction of complexity and the creation of order from a large variety of individual sequences (Hansen and Lorentzen, Reference Hansen and Lorentzen2019). Indeed, the main purpose of this technique is to detect the order, or patterns, in a sequence of events or states that are observed for a given set of actors (Cornwell, Reference Cornwell2015).

Sequence analysis normally proceeds in different steps: first, the data are coded using an alphabet of states that is useful to construct the sequences, then a cost matrix is defined and an algorithm is applied, resulting in a matrix of distances between all pairs of sequences. This matrix is then analysed with a data reduction method like cluster analysis (Abbott and Tsay, Reference Abbott and Tsay2000). The difference between a given pair of sequences is determined by quantifying the transformations needed to turn one sequence into another sequence (Gabadinho et al., Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Mueller and Studer2011; Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Madero-Cabib and Staudinger2018). There are several approaches to this calculation. Some of them consider the order of the event to be more important than the timing; others consider timing to be more important than order (Lesnard, Reference Lesnard2010). I chose the optimal matching approach. Optimal matching analysis is a procedure that counts the ‘costs’ needed to transform sequence A into sequence B and vice versa by counting the minimum number of transformations needed. Two types of operation are possible: substitution and insertion/deletion. The dissimilarities are calculated by comparing each sequence with each other (Cornwell, Reference Cornwell2015). To explore the robustness of the findings, I tried several cost specifications and chose the above-mentioned because it generated the most distinct cluster specification indicated by several cluster cut-off criteria.Footnote 1

It is then possible to perform a cluster analysis on the resulting distance matrix, which allows homogeneous groups of sequences to be created, which, taken together, represent types of trajectories (Gauthier et al., Reference Gauthier, Widmer, Bucher and Notredame2010). For this purpose, I use Ward's cluster analysis (Ward, Reference Ward1963). To determine the most appropriate number of clusters, I considered several cluster cut-off criteria, including the Average Silhouette Width and Point Biserial CorrelationFootnote 2 (Hennig and Liao, Reference Hennig and Liao2013; Studer, Reference Studer2013) that identify the most discriminant number of groups. The Average Silhouette Width ranges between 0 and 1. Higher values indicate a more discriminant grouping. Values greater than 0.25 suggest that there is a meaningful structure in the data that is captured in the respective grouping (Studer, Reference Studer2013).Footnote 3

Status alphabet

For the construction of the sequences, the respondents enter into the analysis at 20 years of age and they are followed until they are 50 years of age (I chose these age cut-off criteria to start observing people once they leave the education system and finish observing them when the transition to retirement normally becomes possible). For the current analysis, five distinct and mutually exclusive work statuses were defined every year, for a total of 31 years. The variables used to define the status alphabet collect the information about the yearly work status and hours worked (part-time or full-time). Therefore, the status alphabet is coded into these categories: in education, part-time work, full-time work, unemployed/inactive and retired.

Panel regression analysis

The panel nature of SHARE is extremely valuable for a study on the effects of retirement transition characteristics on wellbeing. The fixed effects regression model is the most common technique to analyse panel data. This model makes it possible to eliminate the effect of potential unobserved factors that remain constant over time. The logic behind this is to express the change in the outcome variable as a function of the changes recorded in the variables that vary over time. The factors that remain constant are eliminated. Hence, I used fixed effects linear regression models to examine the extent to which retirement transition is associated with changes in psychological wellbeing.

This study takes advantage of the longitudinal nature of SHARE to calculate the change in wellbeing between the first respondent observation and various later time-points. Indeed, I have information on several measures/dimensions of respondents’ wellbeing: (a) before the retirement transition (from five years to one year before retirement, depending on when the individual makes the transition to retirement); (b) the year of the retirement transition; and (c) some years after retirement, until the respondent's last observation. The sample is unbalanced: some individuals are observed only until retirement, others until one year after retirement, others until two, three or four years after the transition. In this paper, models were estimated on the different sub-samples defined by each specific career cluster.

Definition of key variables

Life satisfaction

In this analysis, subjective wellbeing is the dependent variable and is measured by life satisfaction on a 0–10 scale with 10 being the most positive satisfaction with life. Shin and Johnson (Reference Shin and Johnson1978) define life satisfaction as a global evaluation of a person's quality of life based on his or her criteria. It is important to underline that these criteria are set by the individual for him- or herself; they are not imposed externally. For example, although health, income, social network and so on may be desirable, individuals may give them differing levels of importance. For this reason, the life satisfaction scale generally asks the person for the overall evaluation of his or her life, rather than summing up satisfaction with specific sectors (Diener et al., Reference Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin1985). It is a measure of subjective wellbeing that evaluates life as whole rather than current feelings and, therefore, integrates long-term developments (Diener, Reference Diener2009). This aspect makes it extremely suitable for studying long-term consequences of life trajectories (Poromanenko, Reference Ponomarenko2016).

Main independent variable: retirement transition

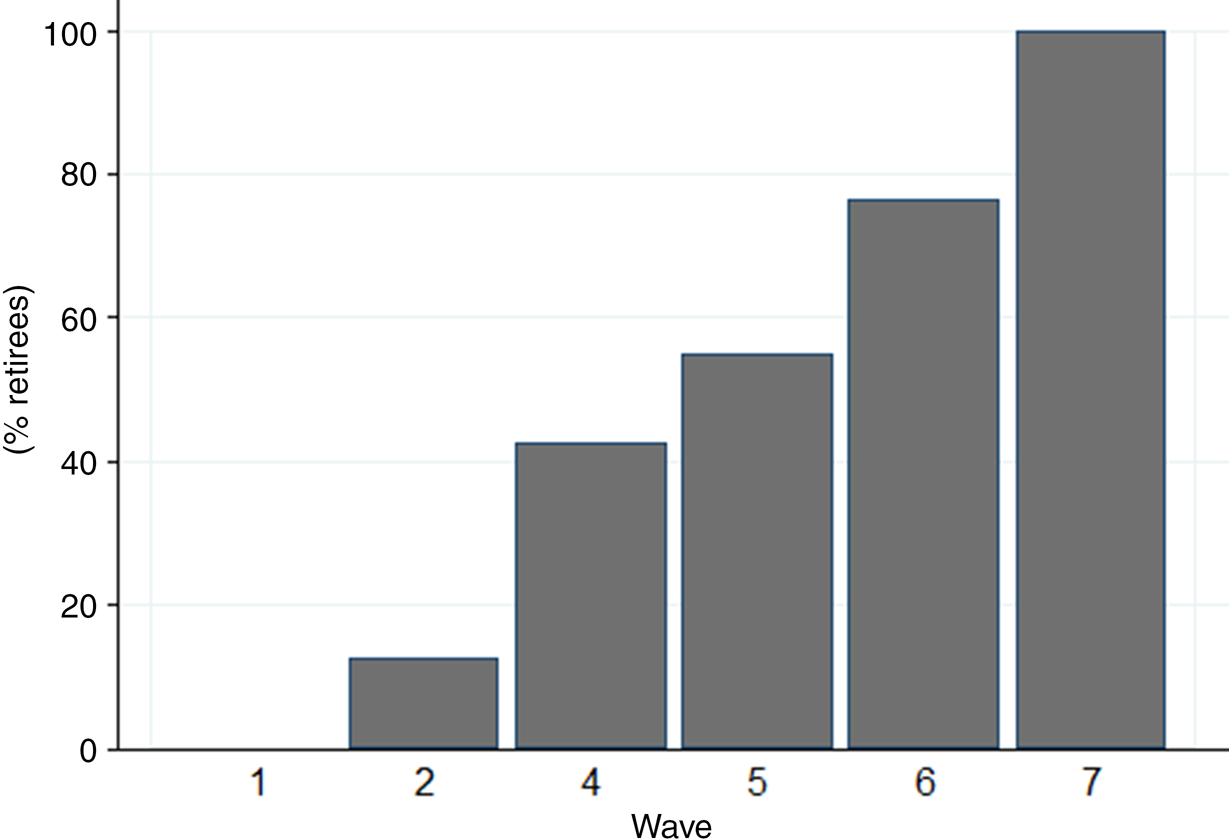

Respondents are asked to best describe their current employment situation from a list of ‘retired, employed, self-employed and unemployed’. Respondents are classified as being retired if they report that they are retired in answer to this question. The percentage of people who are retired increases steadily across each wave of data between 2004/2005 (Wave 1, in which I selected only employed or unemployed people) and 2017 (Wave 7, in which the whole sample is retired) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of retired respondents at each wave, 2006/2007 to 2017.

A variable has been constructed in order to measure retirement transition, i.e. considering time before and after the year of retirement.Footnote 4 It is a ‘time variable’, constructed from the six waves of SHARE as illustrated in Figure 2. This time variable represents the period before retirement (coded −5 to −1), the transition to retirement (coded 0 for the year of retirement) and the period after retirement (coded 1–4) for all respondents included in the sample. Since the sample is not balanced, not all the respondents are present from Time −5 to Time 4.

Figure 2. Specification of time variables.

Note: W: Wave.

Covariates

The literature on wellbeing has found a large variety of demographic, economic, familial and social network-related variables to be significant in predicting levels of wellbeing and their variation (Herzog and Rodgers, Reference Herzog and Rodgers1981; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2001). In this analysis, I include a number of these factors – of course excluding time-invariant ones – as control variables when analysing the effects of retirement on wellbeing. The distribution of the variables used in the analysis and the main characteristics of the analytical sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (observed the year before retirement)

Notes: ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education. IADL: instrumental activities of daily living. SD: standard deviation.

First of all, poor health has been found to have significant negative effects on mental wellbeing among retired people (Midanik et al., Reference Midanik, Soghikian, Ransom and Tekawa1995; Dwyer and Mitchell, Reference Dwyer and Mitchell1999). People in good health are more likely to make successful retirement adjustments than those in poor health (De Vaus and Wells, Reference De Vaus and Wells2004; Bender and Jivan, Reference Bender and Jivan2005). Healthy people may engage in a greater range of activities and opportunities for access to social support than those who are less healthy, thereby helping to increase quality of life in retirement (Heybroek et al., Reference Heybroek, Haynes and Baxter2015). Therefore, I included in the analysis the presence of limitations with instrumental activities of daily living as a categorical variable (no limitations, one or more limitations) and also the self-perceived health variable (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor). Family transitions, in later life too, have also been found to be associated with varying retirement experiences (Szinovacz and Ekerdt, Reference Szinovacz, Ekerdt, Blieszner and Bedford1995) and with changes in subjective wellbeing. First, marital status has been shown to be related to wellbeing among old people (Barer, Reference Barer1994; Hilbourne, Reference Hilbourne1999; Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2001), as well as in the general population (Haring-Hidore et al., Reference Haring-Hidore, Stock, Okun and Witter1985; Kurdek, Reference Kurdek1991). Family relationships can provide social and psychological benefits, suggesting that people who are in a relationship may report a higher level of life satisfaction in retirement than those who are divorced, separated, widowed or single (Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1996; Szinovacz, Reference Szinovacz, Adams and Beehr2003). People living without a partner are less likely to have strong networks of support in retirement and may be at risk of loneliness (Wolcott, Reference Wolcott1998; Heybroek et al., Reference Heybroek, Haynes and Baxter2015). Hence, in this analysis, I controlled for the effect of change in civil status, looking at co-habitation and coding it into three categories: (a) if the respondent is living with a partner/spouse, (b) if the respondent is not living with a partner/spouse, and (c) if the respondent becomes a widow. These categories include women who are (were) in a co-habiting relationship without distinction between married and unmarried. I controlled also for the effect of becoming a grandparent (not having grandchildren, having grandchildren). Furthermore, former studies suggest that changes in the economic situation are also important in explaining adaptation and wellbeing (George, Reference George, Cutler, Gregg and Lawton1992; Holden and Kuo, Reference Holden and Kuo1996); other socio-economic factors such as social class and level of education are also significant predictors of wellbeing among retired people (Dahl and Birkelund, Reference Dahl and Birkelund1997). In order to account for the economic situation, I controlled for a measure that asks the respondent whether his or her household has the ability to make ends meet. This variable ranges from 1 (‘with great difficulty’) to 4 (‘easily’). As a consequence of using fixed effects, I do not need to specify time-invariant variables such as gender, country of residence or education level.

Results

Sequence analysis and working history

The cluster cut-off criteria suggest seven clusters as the best grouping. Figure 3 illustrates the groups of working trajectories as state distribution plots from 20 to 50 years of age (Gabadinho et al., Reference Gabadinho, Ritschard, Mueller and Studer2011). State distribution plots show, at each age, the distribution of employment statuses. Unlike sequence index plots, where individual sequences are chronologically ordered, state distribution plots reduce individual information to general proportions and gather individual sequences into more holistic and abstract clusters, facilitating interpretation (Ponomarenko, Reference Ponomarenko2016; Calvo et al., Reference Calvo, Madero-Cabib and Staudinger2018).

Figure 3. Seven-cluster solution. Employment history (20–50 years of age).

Notes: Freq.: frequency. disc.: discontinuity. OLM.: out of the labour market.

The first cluster, named ‘Full-time employed’, is the largest group and accounts for 45 per cent of the final sample. This group represents the standard model of continuous full-time employment. The second cluster, ‘Mixed’, accounts for 8 per cent of the sample. Here, women have had mainly a full-time working lifecourse, interspersed with many years of part-time work and some periods of inactivity, particularly in the middle of the observational period. The third cluster is called ‘Late entry and full-time employed’ and accounts for 8 per cent of the sample. Women in this group enter the labour market around 25–28 years of age – because they stay longer in education – with a full-time job, and then they have a continuous career. The fourth group is the ‘Long-term inactivity’, which accounts for 10 per cent of the sample. Women in this group enter the labour market with a full-time job and exit around 25–30 years of age. Around 45 years of age, some of them re-enter the workforce again with a part-time or full-time job. The fifth cluster is called ‘Mid-life discontinuity and full-time’. This course is followed by 5 per cent of the women in the sample and it is characterised by a full-time trajectory interrupted by periods of inactivity from 25 to 35 years of age. The sixth group, the ‘Mid-life discontinuity and part-time’ cluster, accounts for 11 per cent of the sample. Like in the fifth cluster, women in this group have a career interruption at around 25 years of age, but re-enter the labour market (around 10 years later) with a part-time job instead of a full-time one. The last cluster is called ‘Part-time employed’ and is followed by 12 per cent of the sample. Women in this group follow a continuous part-time trajectory.

Table 2 reports the main sociodemographic characteristics of each of the sub-samples defined by the work trajectory, i.e. clusters. Across the clusters there are large differences in the distribution of the educational level and the number of children. In particular, the woman educated to higher levels (International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 5 and 6) are prevalent in clusters 1, 3 and 7, and those receiving a lower level of education (ISCED 0 and 1) are prevalent in clusters 4 and 5. Regarding the number of children, the percentage of women with two or more children is higher in groups with an atypical or discontinuous trajectory compared to the continuous and full-time pathways (clusters 1 and 3).

Table 2. Descriptive information of seven groups of working trajectories (observed the year before retirement)

Notes: ISCED: International Standard Classification of Education. OLM: Out of the labour market.

Fixed effects regression models

Figure 4 shows the result of the fixed effects regression model including only the main independent variable. It accounts for the years before and after retirement, to assess how the association between retirement transition and life satisfaction varies across the different clusters/sub-samples, as defined by their working trajectories.

Figure 4. Predictive margins of retirement transition on life satisfaction by career trajectory, fixed effects without covariates (95% confidence intervals are shown).

Looking at the different working trajectories, we notice that the pathways 7 (part-time employed) and 6 (mid-life discontinuity and part-time) have a higher general level of wellbeing than the other trajectories. The greatest change in the level of wellbeing between the years before retirement and the retirement year is shown by groups 2, 4 and 5, which manifest an increasing trend in life satisfaction starting one or two years before the transition to retirement. For groups 2 and 5, we can notice a decline in life satisfaction, starting in the year of the transition. In the case of group 4 (long-term discontinuity), the increase continues until one year after retirement and then the level of life satisfaction remains fairly stable (there is only a slight decrease). As for the other clusters, the change in subjective wellbeing before and after retirement seems very minimal, particularly for group 1 (full-time employed), for which the displayed curve is almost flat.

Table 3 shows the results of the fixed effects regression models (with all the covariates), again divided by career trajectory. For cluster 1 (full-time employed), the effect of the independent variable is positive for each category compared with the reference one, which is two or more years before retirement. Nevertheless, the coefficients are very close to zero (0.02, 0.05, 0.06, 0.01) and are not statistically significant.

Table 3. Fixed effects regression model on life satisfaction scale divided by career trajectory

Notes: Ref.: reference category. IADL: instrumental activities of daily living.

Significance levels: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Group 2 (mixed) shows positive and quite large coefficients for all the categories compared to the reference one: there is an increase in life satisfaction as we move closer to the retirement transition and also once the women have retired. These results suggest a continuous increment in the level of life satisfaction (only two categories have statistically significant coefficients). The effects of retirement transition for cluster 3 (late entry and full-time employed) could indicate a continuous decrease in life satisfaction levels over time, however, the coefficients are not statistically significant. Cluster 4 (long-term discontinuity) manifests a positive increment in life satisfaction starting the year of retirement and it is continuous over the entire retirement process (the coefficient is significant only one year after retirement). The fifth pathway manifests a trend in life satisfaction that seems to increase in the year of retirement (0.7) and one year after retirement (0.6), but then decreases again for the category ‘2+ years retired’ (−0.2). However, the coefficients are not statistically significant. The sixth group shows a similar pattern compared to the cluster just mentioned. About that, it should be added that the small sample size of some clusters (e.g. cluster 5) affects their statistical power and the statistical significance of the variables in the models. To conclude, cluster 7 (part-time employed) shows positive and significant coefficients: the level of life satisfaction increases continuously during and after the retirement transition.

Regarding the covariates, a worsening of health conditions leads to a decrease in the level of life satisfaction for all clusters. Furthermore, the results of the analyses indicate that, in general, the economic situation plays a role in determining the level of wellbeing: unsurprisingly, the shift to a difficult economic situation reduces the quality of life. The effect of the presence of family networks is different across the clusters considered. I find that becoming a grandparent seems to have an effect close to zero for some clusters but increases wellbeing for others; however, the coefficients are not statistically significant. Moreover, becoming a widow decreases the level of life satisfaction for many of the clusters (though it is significant only for the third, fourth and seventh groups).

Figure 5 shows linear predictions from the previous fixed effects models. Although, in some cases, the standard errors are large, these figures graphically confirm that being retired is associated with an increment in the level of life satisfaction for the second, fourth and seventh groups. Women in the fifth and sixth clusters, on the other hand, perceive a decrease in wellbeing starting from the retirement year. Those in the first clusters seem to perceive a sort of continuity in life satisfaction levels throughout the observation period. Finally, women in group 3 experience a continuous decline in their levels of life satisfaction that starts two or more years before retirement and greatly worsens during the year of the transition.

Figure 5. Predictive margins of retirement transition on life satisfaction by career trajectory (95% confidence intervals are shown).

Discussion

With increasing female retirement across many Western societies, questions arise regarding the characteristics of retirement itself. While previous research has mainly focused on predictors proximal to the retirement transition, and on men, this paper investigates the consequences of retirement from paid work for the overall wellbeing of women, and, most importantly, how these consequences vary across women who have experienced contrasting paid-work career trajectories. Overall wellbeing is expressed by the life satisfaction indicator.

In line with the lifecourse theory (Elder et al., Reference Elder, Johnson, Crosnoe, Mortimer and Shanahan2003), the results show that work histories, in addition to other well-known factors, such as a woman's health and economic situation, are crucial in explaining changes in wellbeing after retirement. In particular, some of the trajectories constituted of discontinuity or part-time periods (clusters 2, 4 and 7) showed a continuous increase in life satisfaction throughout the retirement transition. This result can be explained by the fact that women with this type of trajectory may have developed ‘alternative’ roles to that of ‘worker’ during their lifecourse to a greater extent than other women. For example, they could have exited the labour market, or have opted for a part-time job, in order to take care of children or other family responsibilities. In my case, the retirement transition not only seems to be easy but apparently increases wellbeing for women in those clusters. The rise in life satisfaction could be due to two dynamics: on the one hand, after the retirement transition, these women could have more time to spend with their family or for leisure. On the other hand, they no longer have to face great difficulties in reconciling work and family demands.

How do these findings fit into the existing literature? At the descriptive level of working histories, the findings – showing seven career pathways – are in line with previous results that indicated a great complexity of working pathways in the case of women (Macmillan, Reference Macmillan2005; Widmer and Ritschard, Reference Widmer and Ritschard2009). However, in contrast to previous findings, the present results are not based on single-point measures or on specific characteristics of work history (e.g. involuntary job losses, frequent job changes or periods of unemployment) (Bambra and Eikemo, Reference Bambra and Eikemo2009; Wahrendorf et al., Reference Wahrendorf, Dragano and Siegrist2013; Wahrendorf, Reference Wahrendorf2015). Rather, the focus was on entire working histories where five different work statuses were considered. With regard to the investigated associations between work histories and life satisfaction, the results supplement the previous findings, which argued that women who decreased their engagement in the labour market in some periods (such as those with part-time or discontinued careers) and have taken advantage of alternative roles experience an easy transition to retirement. Indeed, alternative roles should moderate the influence of retirement on the subjective wellbeing dimension (Ryser and Wernli, Reference Ryser and Wernli2017). Again, other studies (e.g. Wahrendorf, Reference Wahrendorf2015) suggested that the best quality of life was found among women with mixed histories (domestic work and employment) whilst women with regular histories (continued employment) had a lower quality of life (Wahrendorf, Reference Wahrendorf2015). In my case, women with mixed or part-time histories benefit from the retirement transition in terms of subjective wellbeing. Moreover, the results partially support the continuity theory, according to which retirement may offer the opportunity to spend more time in the roles of friend and family member (Reitzes et al., Reference Reitzes, Mutran and Fernandez1994), offering psychological continuity to retirees. These family and community roles may provide social relationships that enable social integration and increase wellbeing among adults (Reitzes and Mutran, Reference Reitzes and Mutran2004).

The paper has some limitations. First, the fixed effects regression approach did not permit the inclusion of institutional variables that could capture differences in the pension systems. This restricts the possibility of drawing specific policy conclusions based on this paper or comparing different institutional contexts. Moreover, the choice to carry out the analysis on a pooled sample of 11 European countries is due to the small sample size. I am aware that contextual differences between countries can affect people's response to life changes and subjective wellbeing; however, deciding to focus on one or a few countries would have greatly decreased the sample size, invalidating its statistical power. Future literature should analyse data on individual countries or focus on the differences between different institutional contexts. A second limitation is that I use a self-reported measure to distinguish between being employed/unemployed or retired, and exclude those respondents who report themselves differently (e.g. as being a home-maker). I recognise that the self-reported measure of the work status can differ from administrative data. It is possible that respondents from the sample that consider themselves not retired but receive pension benefits have been excluded. Finally, it would also be interesting to use other indicators to measure the level of wellbeing or to investigate the effect of other life domains (such as the family trajectory) on female life satisfaction.

Despite these limitations, this study has many strengths. It offers advances in terms of new research questions and methods. First, I considered patterns of employment from youth to middle age. Using sequence analysis, I was able to observe the differences in women's work trajectories over 30 years. This technique allows us to differentiate careers characterised by full-time employment, part-time work, and a combination of paid work and long or short breaks. The clustering provides a parsimonious model that allows the association between life events and later-life outcomes to be studied (Zella and Harper,2020). Second, due to the richness of the SHARE data, I was able to take into account the changes in life satisfaction, taking into account important covariates. Results show that the retirement transition affects the level of life satisfaction differently, depending on the longitudinal working trajectories. Therefore, through the application of a recent methodological approach to handling lifecourse information, I can broadly enlarge the perspective on the work models typically followed by women and on the outcomes they have in old age. From a lifecourse perspective, the question of how different types of work patterns can influence future outcomes (e.g. life satisfaction) can now be addressed in a new and very promising way. Sequence analysis provides a rigorous methodology for visualising and interpreting work (and other) trajectories as process outcomes, and fixed effects regression models make it possible to observe the intra-individual changes. My results focus attention on the relevant question of how women can combine work and family, and how this combination can influence the structure of their working career and, consequently, their wellbeing in later life. Moreover, it would be extremely important to think about how social policies could advance wellbeing, considering how they could play a role in shaping individual and context-specific trajectories.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.