Observers of the American mental health system often lament that people seeking its help have “nowhere to go.” Consider, for example, E. Fuller Torrey’s influential 1988 book Nowhere to Go: The Tragic Odyssey of the Homeless Mentally Ill, or the more contemporary press attention given to the issue, such as the 2014 CBS 60 Minutes report “Nowhere to Go: Mentally Ill Youth in Crisis” and the USA Today investigative piece “Cost of Not Caring: Nowhere to Go – the Financial and Human Toll for Neglecting the Mentally Ill” of the same year. The assumption I made that late Philadelphia evening I described in the Preface is, unfortunately, a nationwide reality.

Similar language is used in other countries. Note the title of a 2020 report from the Australian College of Emergency Medicine: “Nowhere Else to Go: Why Australia’s Health System Results in People Getting ‘Stuck’ in Emergency Departments.” Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, a headline in The Guardian bemoans the absence of mental health services, reading: “‘She Was Left with No One’: How UK Mental Health Deteriorated during Covid.” In Canada, the largest mental health and addiction teaching hospital, the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, premiered the film Nowhere to Go: A Brokered Dialogue to raise awareness about the mental health issues faced by LGBTQ homeless youth. This observation – that mental health systems are too meager to attend to societal needs – seems universal.Footnote 1

This chapter questions that claim. Previously unexplored international data shows that it is only in select societies – those that have had the greatest influence on scholarly perceptions of mental health care – that its users have nowhere to go. In many other countries, the supply of mental health care is much higher. Moreover, and contrary to the presumptions that guide global mental health care policy-making, these understudied countries provide both ample community care and ample inpatient care. The wide variation in the contemporary supply of mental health services across affluent democracies is surprising for several reasons. These differences align with neither the existing scholarly typologies of social policy systems nor those of health policy systems. Furthermore, these variations are present despite all countries’ shared history of psychiatric deinstitutionalization, a process conceptualized and documented using an original historical data set. I then turn to proposing an explanation for these differences and developing an empirical strategy to assess it. I focus on the cases of the United States and France, along with Norway and Sweden, in order to control for a range of case-specific alternative hypotheses. The chapter concludes with brief descriptions of the mental health care systems in each of the four countries examined in this book.

Contemporary Differences in the Supply of Mental Health Care across Countries

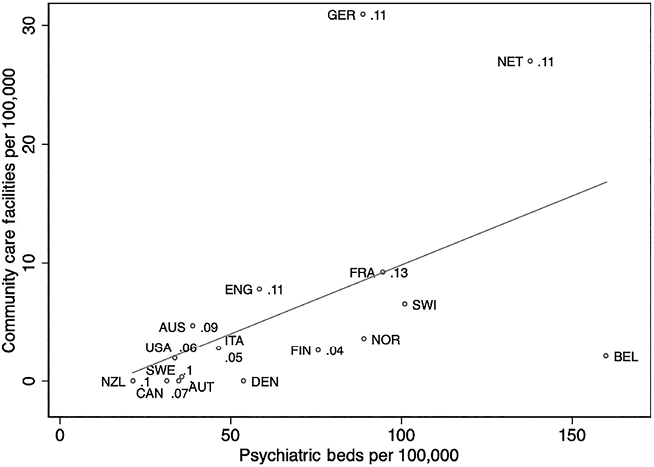

Figure 2.1 plots the supply of mental health care across 16 affluent democracies. The data is drawn from the World Health Organization (WHO), which sends a standardized questionnaire to in-country experts, usually government officials, who submit national statistics on their mental health system according to set definitions. Although an incomplete reflection of case-specific particularities, the figure presents an adequate snapshot of general trends across countries, using the most recent year available (see Perera Reference Perera2020c). The 16 countries included were the first in the world to deinstitutionalize, since their early industrialization prompted the rise of the asylum, and their postwar economic prosperity prompted its decline.Footnote 2 As a result, the shared experiences of these countries have framed global expectations in mental health, presuming that other countries will follow similar policy patterns as their economies develop.

Figure 2.1 Scatterplot of psychiatric beds and community care facilities per 100,000 population in 16 high-income democracies and percentage of the public health budget spent on mental health (as available), with line of best fit

Figure 2.1 reveals three important dimensions of variation in mental health care across countries. First, and despite the “nowhere to go” refrain, people with mental illnesses do have somewhere to go, in some countries. The supply of services in Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, and Norway is much higher than in New Zealand, Canada, Sweden, Australia, Austria, the United States, and Italy. Second, the composition of services in the high-supply group includes both ample “institutional” care and ample “community” care. Institutional care, or hospital-based overnight care for people with mental disorders (operationalized in Figure 2.1 as psychiatric beds per 100,000) has gained a negative reputation among mental health specialists, who often view it as the outdated vestige of psychiatry’s asylum period (WHO 2014a). They instead prefer community care, or non-hospital-based and outpatient care for people with mental disorders (operationalized as outpatient and day facilities per 100,000).Footnote 3 Nonetheless, countries with a generous supply of mental health care tend to include high amounts of both types of services. Moreover, countries at the higher end of the supply spectrum also tend to provide inpatient care in psychiatric hospitals, while those in the middle and at the lower end of the spectrum are more likely to deliver inpatient care in general hospitals (author’s calculations using WHO 2011, not shown, see also Perera Reference Perera2020a). In other words, countries that devote resources to separate psychiatric facilities appear to supply more inpatient care than those that do not. Third, the numbers to the right of each data point indicate, where available, the percentage of the government health budget allocated to mental health.Footnote 4 For the most part, countries that spend more of their public health budget on mental health tend to supply psychiatric care in greater quantities than those that do not.Footnote 5 This trend makes the mental health sector distinct from general health care, where the public sector accounts for far less of the supply of care (see also Perera Reference Perera2019). Unlike general health services, mental health services are far more labor-intensive and serve more destitute clients, a combination of factors that renders mental health care costly and private investment unlikely.

These intertwined three dimensions of variation in mental health care systems therefore run counter to the presumptions that permeate global mental health policy paradigms. Consider the title of a press release from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD): “The Netherlands has an innovative mental health system, but high bed numbers remain a concern” (OECD 2014). The persistence of inpatient care, despite an otherwise admirable performance record, is presented as a paradox. Implied here is the notion that a modern, expansive psychiatric system should shrink the supply of inpatient care and replace it with outpatient care instead. Yet the largest mental health systems provide ample institutional care as well as community care. Contrary to international expectations, these two types of services appear to be complements, not substitutes (Perera Reference Perera2020a). Their dependence on generous public financing, moreover, also challenges arguments that advocate for private investment in this policy area (Perera Reference Perera2020b).

These three intertwined dimensions in fact are preconditions for a high-quality mental health system. Measuring the quality of mental health care is a notoriously challenging task (see the forum debates in World Psychiatry 2018). Much depends on the particular diagnosis of the user. For example, an adult experiencing clinical depression may require frequent access to a combination of psycho-therapeutic services and psycho-pharmaceuticals, provided in the daytime. Meanwhile, a child with autism might require pediatric behavioral and communication therapies. Other patients, such as those who experience psychotic episodes, may require periodic access to dignified overnight care. Complicating quality measurements further are the complex ethical issues that arise in mental health care. Patients do not always consent to receiving services, either because they do not believe they need them (a condition known as anosognosia) or simply because they are uncomfortable with what providers recommend. Moreover, what constitutes a “cure” in this area is often different than in general health care. Many conditions are chronic and recurring, such that successful service users often prefer to self-describe as “in recovery” rather than simply “recovered.”

Nonetheless unifying these patient experiences is the need for widely available, comprehensive, and varied mental health care services, at low cost to the user. Experts agree that a “balanced” set of services ensures that all patients receive what they need, when they need it (Thornicroft and Tansella Reference Thornicroft and Tansella2013). These services include those indicators captured in Figure 2.1: outpatient facilities where the patient experiencing clinical depression might obtain regular access to psychotherapy and pharmaceuticals, day care facilities where the child with autism might obtain psycho-pediatric services (and their parent might obtain relief from childcare responsibilities during the workday), and overnight inpatient services where the patient experiencing psychosis might obtain support for stabilization. Without these services, their conditions would remain untreated. Only an acute episode (e.g., a panic attack for the child, a suicide attempt for the adult with depression) would trigger contact with a hospital’s stressful emergency department, hardly the site to relieve psychiatric trauma.

The public financing indicator in Figure 2.1 helps to capture how much these services cost their users. As I commented in The Lancet Psychiatry (2019), people with chronic behavioral health needs rarely have the means to afford their own care. Mental disability inhibits workforce entry, limiting the income available to cover private and out-of-pocket health care costs. Moreover, long-term mental health treatment requires different, often more complex resources than other health treatments (Franck and McGuire 2000). Public financing of these services is therefore common and necessary. Note that the public financing indicator normally excludes expenditures on psycho-pharmaceuticals. These drugs tend to be much cheaper to provide than labor-intensive care services, so governments tend to pay for them using standard pharmaceutical coverage schemes. More variable and often more consequential for users is whether and to what extent services are covered. When generously funded by the state, such services often result in low (or no) cost to users.

To be sure, Figure 2.1 cannot claim to predict the overall state of mental well-being in a country. First, it excludes information on mental health resources available in the general health system. But to that end, it does suggest a pattern, if perhaps a controversial one. Note that the services deemed necessary to a high-quality mental health system are located in ring-fenced facilities that are not integrated into the general health system. For example, countries with more psychiatric beds tend to house them in specialized psychiatric hospitals, not in the psychiatric wards of general hospitals (see WHO 2011, also Perera Reference Perera2020a). Such ring-fencing may over-medicalize mental health (leaving less room for counseling and other less biomedically intensive social services) or make it difficult to integrate mental health care into the primary health system (an often lauded goal, see WHO 2014a).

Second, Figure 2.1 excludes the numerous other policy areas that support mental health. The person experiencing clinical depression, for example, may benefit from employment accommodations or disability insurance payments. The child with autism may benefit from specialized educational services. The person experiencing psychosis may require long-term housing assistance. Such “wrap-around” supports and structural factors matter greatly for overall psychological well-being (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Balfour, Bell and Marmot2014; Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Wibbels and Wilkinson2015; WHO 2014b); however, the primary purpose of this book is to explain variations in the clinical services that address immediate mental health needs.

Put simply: To ensure high-quality mental health services, governments must first supply services. The noun is a prerequisite for its adjective. This data demonstrates that governments differ in the extent to which they succeed at that initial step. The varying supply presented in Figure 2.1 suggests that (1) some countries do provide mental health care at higher rates than expected by the “nowhere to go” narrative, (2) those high-supply countries tend to provide that care in both outpatient and hospital settings, and (3) mental health care supply depends heavily on public, not private, funding. The next section explores alternative explanations for these differences.

Alternative Explanations

To explain the puzzling differences in mental health care supply across countries, one might consider three alternative explanations. The first two, concerning the extent to which these differences align with cross-national differences in social welfare systems or health care systems, lose much of their explanatory power with a simple glance at Figure 2.1. The third, concerning the extent to which these differences result from varying historical differences in mental health care, requires a bit more unpacking. I will discuss that explanation in more depth after reviewing the first two, though it, too, is insufficient.

First, does a given country’s “world of welfare” predict its mental health system? If Esping-Andersen’s (Reference Esping-Andersen1990) classic three-part typology of social welfare systems could explain mental health care systems, each country’s placement in Figure 2.1 would be similar to that of others with similar social welfare systems. In other words, the “liberal” anglophone countries of Europe, North America, and Oceania, the “conservative” countries of continental Western Europe, and the “social democratic” countries of Nordic Europe would form distinct clusters on the graph. But this typological sorting is not visible in the figure. Although some of the smaller, more privatized welfare states of the liberal countries cluster at the lower end of the spectrum, others (Australia, England) supply mental health care at higher levels than the rest. Meanwhile, the generous social democratic welfare states, which typically supply public services at high levels, provide widely different amounts of mental health care (see the varying positions of Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Norway). Continental European welfare states, whose attributes place them in between the liberal and social democratic extremes, furthermore, hardly follow any patterns at all. Austria supplies mental health care at levels similar to both Canada and Sweden (a liberal and social democratic social welfare system). Yet some of Austria’s continental siblings, Germany, Belgium, and the Netherlands, sit on the other end of the spectrum and off the line of best fit. As such, the factors that explain the variation in social welfare systems, in particular the political power afforded to the Left, would be unable to fully explain the variation in mental health care systems.

Second, does a given country’s general health system predict its mental health care system? General health systems can vary in many ways, but one central dimension of variation is the relationship between providers (typically, physicians) and the government. Where providers have less autonomy, governments have more control and often oversee a fully public, state-owned health care system. Yet it is not clear that the supply of public mental health care is also greater in these countries. If that were the case, the supply of mental health care and the generosity of public financing would be universally high in countries with a national health service (i.e., Britain, Italy, and the Nordic countries), but it is not. It is curious that some countries with social insurance systems (e.g., Belgium, France, Germany) provide far more public mental health care than many of the national health service countries. But even within that subset of countries, there is significant variation in the quantity and distribution of mental health care services (e.g., low overall supply in Austria, higher-than-average community care in Germany, high inpatient care in Belgium). Since providers tend to have more bargaining power over the state in these countries, it is possible that those working in psychiatry may have greater institutional tools at their disposal to advocate for better pay and protections. But I will argue that the degree and scope of their success depends on other factors, namely their prospects for coalition with providers across occupational strata. As a result, what might explain the varying relationships between governments and providers across countries, such as the presence of institutional veto points, cannot wholly account for the variation in mental health care systems (Immergut Reference Immergut1992).

Other health system typologies fail to explain the variation in mental health care services as well (for a review, see Wendt and Bambra Reference Wendt, Bambra and Aspalter2020). For example, countries with a high overall supply of general health care, public and private, do not necessarily have a high supply of mental health care as well. Neither do Reibling’s (Reference Reibling2010) “low supply” health care systems, such as Denmark, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, provide especially low levels of mental health care; nor does Moran’s (Reference Moran2000) paradigmatic “supply state,” the United States, provide especially high levels of it. Another example: Typologies that focus on the user experience in the general health system do not appear to account for that of the mentally ill. The “social democratic” health systems, for instance, reduce the extent to which patients must depend on the market for care (i.e., the extent to which the patient is “de-commodified,” see Bambra Reference Bambra2005). Yet many of these countries, such as Canada, New Zealand, and Sweden, supply very low levels of public mental health care. The experiences of patients with mental illness, then, are different from those of others. In short, mental health care systems stand apart, producing politics, services, and experiences that do not resemble those in the general health system.

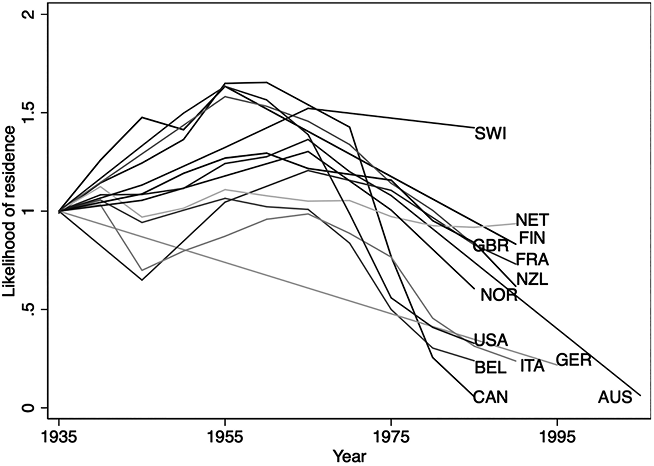

A third possible explanation considers the role of legacy: Does a given country’s historical supply of mental health care predict its current supply of care in this area? Perhaps the countries with high levels of institutional care never deinstitutionalized in the first place. Or perhaps prior levels of inpatient care can explain contemporary levels. Assessing the validity of this genre of explanation requires both developing a clear, portable definition of deinstitutionalization and collecting the appropriate longitudinal and cross-national indicators. As the coda to this chapter describes, I define (psychiatric) deinstitutionalization as a society’s movement down a continuum, in which the mentally ill become less likely to reside in an establishment that provides both psychiatric and custodial care than in the past. To measure this process across the full universe of cases (the 16 countries in Figure 2.1), editions of each country’s national statistical yearbook were surveyed to obtain data from before, during, and after deinstitutionalization, from 1935 to about 2000 (see the Appendix for more information). Although not all indicators were available for all countries and all years, most of the yearbook editions consulted included some information on three of the most important indicators: the residential population, the number of mental hospitals, and the number of psychiatric beds.

To assess whether all countries deinstitutionalized, Figure 2.2 draws on an original data set (see the Appendix) to plot the primary indicator of this process: the proportion of residents in mental hospitals per 100,000 population in a given year, compared to the historical baseline (1935). It shows that all countries deinstitutionalized the resident population of mental hospitals, though the extent to which they did so varied substantially. In most cases, the likelihood of institutionalization in fact increased after the Second World War but began to decrease by the 1970s. An exception to this pattern is Switzerland, where institutionalization rates remained high in the 1970s and 1980s; and unfortunately no recent residential data is available for that country, so what happened after that period is unclear. The figure also suggests that historical levels of institutionalization cannot predict what occurred during deinstitutionalization itself. For example, countries that had some of the highest postwar rates of institutionalization, such as Canada and Australia, eventually came to have some of the lowest.Footnote 6

Figure 2.2 Residents of psychiatric hospitals per 100,000 people, relative to a 1935 baseline, available countries and years

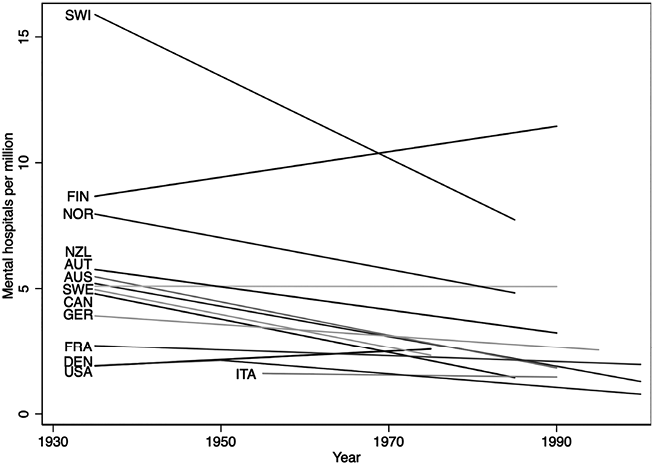

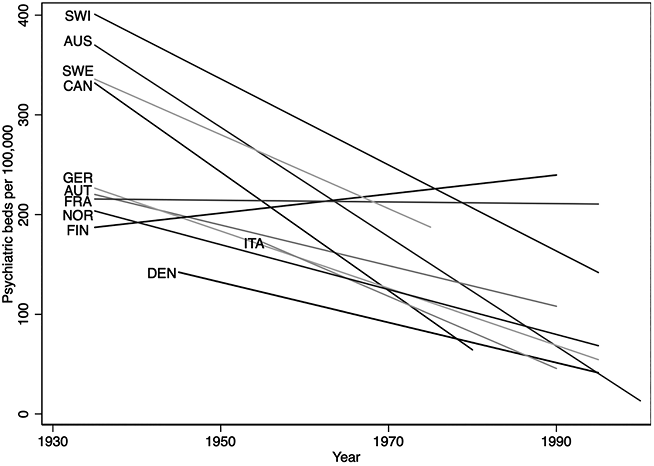

To assess whether historic differences in inpatient care explain contemporary differences, Figures 2.3 and 2.4 plot observations from the original database on the supply of mental health care – hospitals and beds, respectively – in these countries.Footnote 7 They do not. While the supply of mental health care in countries like Austria, Australia, Sweden, and Canada was once above average, it is now well below it (compare to Figure 2.1). The opposite is true for countries such as France and Germany. In the case of Finland, institutional services even increased (even as the population residing in them decreased, see Figure 2.2). Also worth noting is that, prior to 1935, these countries governed public mental health services in very different ways. As Ansell and Lindvall (Reference Ansell and Lindvall2020, table 7.1, 183) document, state control of asylums was common in Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, New Zealand, Norway, and Sweden; yet that control did not seem to stall the reduction of public institutional care in those countries with any consistency. In fact, contemporary levels of public mental health supply now vary widely.Footnote 8

Figure 2.3 Mental hospitals per million people, 1935–2000, available countries and years

Figure 2.4 Psychiatric beds per 100,000 people, 1935–2000, available countries and years

Together, Figures 2.2–2.4 hence challenge the notion that countries with historically high levels of mental health care, especially institutional care, did not deinstitutionalize at the end of the 20th century. That all countries eventually deinstitutionalized makes theoretical sense, even if not all cases have been closely documented by historians and country experts. Following Scull’s (Reference Scull1984) structural explanation for deinstitutionalization, in each of these countries favorable economic conditions in the postwar period expanded social insurance programs that would facilitate life outside the asylum, and the unfavorable economic conditions that followed in the 1970s and 1980s prompted governments to close costly inpatient mental health services. With the new antipsychotic medications, hospitals could reduce coercive restraint and outpatient treatment became more feasible. Developed by the French pharmaceutical company Rhône-Poulenc in the 1950s, chlorpromazine (also known under the trade names Thorazine and Largactil) was the first drug to treat psychosis (Grob Reference Grob1991, 146–155; Scull Reference Scull1984, 80). Although it was marketed, prescribed, and purchased in all these societies, chlorpromazine had little effect on the actual closure of hospitals (Gronfein Reference Gronfein1985). In addition, the societal support for deinstitutionalization tended to be high in all western societies in the latter half of the 20th century. These movements, moreover, were transnational. Optimistic postwar reformers from more than 27 countries regularly met in Geneva to discuss their shared ambitions to transform mental health care (Henckes Reference Henckes2009; WHO 1978; see also Roelcke et al. Reference Roelcke, Weindling and Westwood2010). Critics of institutional psychiatric power included Americans such as Erving Goffman, Alfred H. Stanton and Morris S. Schwartz, and Thomas Szasz; their counterparts in the British Commonwealth such as R. D. Laing and David Cooper; as well as non-anglophone thinkers such as Franco Basaglia and Frantz Fanon.Footnote 9 A steadily intensifying media spotlight on some of the most deplorable mental hospitals, accruing legal battles over involuntary commitment procedures, and the revolutionary overtones of the 1960s helped many of these ideas spread around the world. In sum, the three factors that helped to reduce the resident population of mental hospitals – movements, medications, and money – were present across each of these countries.

This data also challenges the notion that prior levels of institutionalization determined contemporary levels. The countries that provide greater levels of inpatient care today have not always done so. Notice also that, while most countries reduced the supply of psychiatric beds over the course of the 20th century, they did not necessarily do so by closing mental hospitals. Ironically, some countries reduced their resident population while increasing or generally maintaining the hospital and bed supply (Finland, France, Germany); Switzerland, meanwhile, saw dramatic supply reductions that do not match its residential trends in Figure 2.2. Since the varying supply of care today does not align with the variations prior to deinstitutionalization, then something must have occurred during deinstitutionalization to shift national policy trajectories. The next section presents a research strategy to explore those changes and test a hypothesis that can explain them.

Research Design

As discussed in Chapter 1, this book proposes that the “welfare workforce” – the workers who depend on the welfare state for their employment – shape social policy, particularly when its clients lack political power and as the underlying economic structure hangs on service industries such as health care and education. Psychiatric deinstitutionalization overlapped with this service transition, such that the increasing numbers of public mental health workers had the opportunity to influence policy in that area. But they were not always successful. Where they had access to political resources and allies, public sector workers were able to secure higher wages, more employment, and generous protections, a combination that results in more public services and feeds resources back into the workforce. This “supply-side policy feedback” process can be either positive or negative. Where workers did not have access to these supports, lower wages, fewer jobs, and layoffs resulted, producing fewer public services (see Figure 1.1, Chapter 1). To predict the likelihood of workers’ success, I hypothesize that independently organized and unified public sector managers are more likely to advocate with their employees and, by extension, increase their political power. The presence of a “public labor–management coalition” – an especially potent alliance that is particular to the public sector – therefore can drive expansions in public services, even when beneficiaries (like the mentally ill) cannot demand them.

Testing the effect of this hypothesis on the development of a macro-level structural outcome such as mental health policy requires case analysis, since it allows paying full attention to the exploration of causes. Careful consideration of the “causes of effects” is a characteristic strength of case study research, for it unveils multilevel, evolving, and often unquantifiable causal factors and mechanisms (Mahoney and Terrie Reference Mahoney, Terrie, Brady, Box-Steffenmeier and Collier2008). If this study is to unpack the political influence of public employees on mental health care, it must consider the shifting preferences of multiple actors (workers, managers, policy-makers) and their multiple representatives (trade unions, associations, government agencies) on various policy issues (inpatient care, outpatient care, public investment in psychiatric services). The same is true of historical developments (e.g., the growth of the public sector workforce, ideological change) and important cross-national differences (e.g., patterns of policy-making, demographic differences). Case studies make it possible to examine each of these complex factors in close detail and to assess their overall causal role more holistically.

Of the countries identified in Figure 2.1, two stand out as especially well-suited for detailed case comparison: the United States and France. The US experience of deinstitutionalization is, by far, the one that has most influenced popular and scholarly understandings of that process. If the proposed hypothesis found empirical support in this paradigmatic case, it would also call international presumptions about deinstitutionalization into question. In particular, evidence suggesting that the absence of a public labor–management coalition in the United States reduced the supply of all public mental health services in the late 20th century would challenge arguments about the functional, apolitical nature of deinstitutionalization, as well as about the necessity of closing hospitals to expand community care. France, by contrast, lies on the other extreme of the supply spectrum compared to the American case (see Gerring Reference Gerring2014). The expansive public mental health system in France developed during – even in spite of – psychiatric deinstitutionalization.

What renders this pairing most apt for comparison, though, is that a mid 20th-century observer could not have predicted these 21st-century policy outcomes (see Mahoney and Goertz Reference Mahoney and Goertz2004). If anything, the opposite might have been more likely. While the two countries shared a similar political economy of mental health care prior to deinstitutionalization and developed similar plans to reform it in the postwar period, policy-makers in the United States initially benefited from better prospects for service expansion. The supply of public mental health care in France had suffered during the Second World War, while infrastructure was more robust in the United States. Moreover, commitment to the reform was stronger in the United States (where Congress enacted it into law) than in France (where an administrative circular merely suggested the idea).

But the possibility of coalition between public sector psychiatric managers and workers differed. In the 19th century, public sector psychiatric managers in both countries organized independently from those in the private sector, but by the early 20th century those in the United States opted to include private practitioners in their membership. This decision would set the United States on a very different pathway to deinstitutionalization after the Second World War. Chapter 3 hence uses the logic of the structured, paired comparison to both document these similar initial conditions and highlight a single difference of causal importance (Slater and Ziblatt Reference Slater and Ziblatt2013; Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010).

Holding constant these otherwise similar initial conditions, US and French mental health policy diverged after the Second World War.Footnote 10 Chapters 4 and 5 therefore separate the two cases, respectively, and use within-case process-tracing techniques to assess the validity of the proposed hypothesis against context-specific alternative explanations in each country. Chapter 4 explores whether the absence of independently organized and unified public sector managers in the United States foreclosed the possibility of coalition with their employees and facilitated negative supply-side policy feedback. Chapter 5 explores whether the coalition’s presence in France enabled the opposite outcomes. Together, these two chapters examine whether and how a public labor–management coalition shaped policy feedback processes in mental health from the 1960s to the 1980s in these two main cases.

An abbreviated comparison of two other cases, Sweden and Norway, examines whether the argument can explain mental health care outcomes elsewhere. These two countries have much in common, such as their generous, state-oriented welfare states and large, powerful public sector workforces. Yet Sweden and Norway diverge widely on public mental health care. In fact, simply crossing the border from Norway into Sweden reduces the inpatient care supply by 60 percent. Community care is higher in Norway than Sweden as well. Support for the hypothesis in these two cases would bolster its predictive power. Analyses of Sweden and Norway can also refute alternative hypotheses that arise in the United States and France. For example, the role of the state is as important in Swedish welfare provision as it is in France (if not more so), yet Sweden did not produce the high levels of public mental health services accomplished by France. The decentralized Norwegian system, meanwhile, did not produce the rapid, “race to the bottom” deinstitutionalization experienced in the decentralized American welfare state. Chapter 6 presents the results of this second paired comparison.

Analyzing these four country cases has additional benefits. Together, they test the argument across all three types of welfare states (liberal America, conservative France, and social democratic Norway and Sweden) and across general health systems that are more oriented toward the private sector (France and the United States) compared to those oriented toward the public sector (Norway and Sweden). These cases also offer an opportunity to revise the standard narrative about better-known cases (the United States and, to some extent, Sweden) as well as to contribute to the English-language literature of lesser-known cases (France and Norway). Across all four cases, deinstitutionalization did occur (the population of patients residing in mental hospitals declined), but its outcomes differed. In the United States and Sweden, hospitals closed wholesale and few community services developed. By contrast, France and Norway kept existing hospital structures open while also expanding community services, in ways perhaps better aligned with the comprehensive goals of deinstitutionalization (see the coda to this chapter). The following section details these contemporary outcomes across the four cases.

Overview of the Four Mental Health Care Systems Selected for Comparison

Countries That Supply Limited Public Mental Health Care Services

The United States

Since psychiatric deinstitutionalization, the supply of public mental health care has declined in the United States. During that time (1960s–1980s), the psychiatric bed capacity of state and county mental hospitals reduced by 70 percent and about one out of every five hospitals closed (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Geller and Pandiani2009). Although some policy-makers attempted to develop and expand a network of public community mental health centers (CMHCs), only a fraction of these 1,200 sites were built. Fewer have been maintained. Today, the vast majority of people requiring outpatient mental health care services must seek it in the private sector, often with hefty user fees (Druss et al. Reference Druss, Bornemann, Fry-Johnson, McCombs, Politzer and Rust2008). Out-of-pocket payments for US mental health services are quite high: about 11 percent of total spending (Garfield Reference Garfield2011). Some inpatient care is available at general hospitals, private psychiatric hospitals, military hospitals, and correctional facilities (SAMHSA 2010, tables 48 and 116). The latter is often a last resort that compensates for the lack of chronic psychiatric care capacity in the general health system.

As a result, access to mental health care is poor in the United States. Only about a third of Americans with mental health problems receive treatment (Cunningham Reference Cunningham2009). Most outpatient visits are restricted to dispensing medication, not therapeutic or rehabilitative services (Olfson and Marcus Reference Olfson and Marcus2010). Moreover, the limitations of public mental health care and financing mean that private psychiatry is not only dominant in the United States but also its accessibility is limited to the most affluent of patients; those who can afford to pay the full cost of these services. Less affluent Americans are more likely to find themselves in prisons or homeless shelters than in psychiatric hospitals or clinics; psychiatric conditions affect about half of incarcerated individuals and about a quarter of chronically homeless individuals (Culhane Reference Culhane2008; James and Glaze Reference James and Glaze2006). In effect, this group has “nowhere (else) to go.”Footnote 11

Contemporary public policies structure these supply and access outcomes. Public mental hospitals, originally financed by state and county mental hospitals, began to close when the federal Social Security program developed in the 1960s and 1970s. Several new social programs incentivized states to shift patients to non-hospital settings. Medicaid, a joint state–federal public insurance program for the poor and disabled enacted in 1965, refused to pay for services in “institutions for mental disease” (IMDs, or specialized adult psychiatric institutions with more than 16 beds; hereafter the “IMD Exclusion”); however Medicaid would pay for long-term care services for the elderly, who composed a significant portion of the institutionalized population at the time.Footnote 12 Those payments, combined with a congressional support for nursing home construction, shifted much of the patient population from state and county mental hospitals to nursing homes. Meanwhile, Social Security Insurance, the disability insurance program enacted in 1972, also discouraged public inpatient psychiatry by denying benefits to individuals living in public institutions, such as state and county mental hospitals. Finally, Medicare, the income-taxed public insurance program for the aged and the disabled, would cover only 190 days of inpatient psychiatric care (in any institution, public or private) over the beneficiary’s lifetime. These changes have weakened the financial support for inpatient mental health care over time.

Community mental health care faced similar policy constraints. Congress enacted the CMHC program for only a few years at a time, limited the funds available for staff, and eventually structured it as a block-grant program. These factors stalled its expansion. Private insurers, which cover about two-thirds of the population, mostly through employment contributions, were not incentivized to cover outpatient care (or inpatient care); so they reimburse providers at low rates.Footnote 13 The same is true for both Medicare and Medicaid. According to Bishop et al. (2014), and as a consequence, only half of psychiatrists accept Medicare and private insurance and only 43 percent accept Medicaid, compared to nearly all physicians in other specialties (86, 89, and 73 percent, respectively). Thus, Chapter 4 will trace the political factors that produced these policy constraints in the United States.

Sweden

Sweden also has a limited supply of mental health care. Although mental health care provision is formally public and universal, public rhetoric has labeled it a “policy failure” and “national disgrace” (see the infamous comments of Social Democrat Lars Engqvist discussed in Chapter 6).Footnote 14 The poor reputation of Swedish mental health care is partly because it is not financially differentiated from general health care. There is no stand-alone fund for mental health care, since it depends on and competes for the same national funds that finance the general health system. As in the general health care system, 80 percent of mental health spending is funded by the national government and through public grants, while out-of-pocket payments account for 17 percent of expenditures (the remaining 4 percent is funded by marginal county and municipal taxes). Mental health care patients pay similar user fees as somatic patients, capped at just over $100 (USD) per year (NOMESCO-NOSOSCO 2022; per Riksbank 2022). Private psychiatric practitioners account for about 7 percent of total mental health care provision in Sweden (Anell et al. Reference Anell, Glenngärd and Merkur2012; Glenngärd Reference Glenngärd2020).

Another factor contributes to the low supply of mental health care in Sweden. As I will discuss in Chapter 6, in the 1990s the government devolved the responsibility for the nonmedical social care of the mentally ill to the municipal level. This move severed incentives for the regions to integrate medical and social – especially residential – services and resulted in significant cost-shifting to municipalities. Only very few dedicated funds are available to compensate them. Here, too, services depend on and compete for the same national funds (and marginal local taxes) for solvency. Significant local discretion in their allocation, moreover, means that services for the mentally ill are often short-changed and vary by municipality, as noted in that chapter.

Countries That Supply Extensive Public Mental Health Care Services

France

Unlike the mental health systems just described, France expanded its mental health care system during psychiatric deinstitutionalization. The 1960s to 1980s saw the development of psychiatric “sectorization” instead. The sectors partition the country into more than 1,200 geographic catchment areas for populations of around 60,000–70,000 people. Each must provide multidisciplinary mental health care, though the precise mix of services depends on the perceived needs of the population.Footnote 15 Nonetheless, sectors include a public psychiatric outpatient care center (centre médico-psychologique) that offers ambulatory mental health care, coordinated by a public hospital (Chevreul et al. Reference Chevreul, Brigham, Durand-Zaleski and Hernández-Quevedo2015). Care is available outside of the sectorization system as well. Although public sectorized services are more diverse and more numerous than private mental health services, the private sector accounts for about 20 percent of inpatient cases and about 50 percent of outpatient psychiatrists (Chevreul et al. Reference Chevreul, Durand-Zaleski, Bahrami, Hernández-Quevedo and Mladovsky2010; DREES 2016). Moreover, sectors are supplemented by a range of “medical-social” services (services médico-sociaux), such as housing, educational support, professional training, and sheltered workshops. The degree of coordination between the sectors and these public or not-for-profit medical-social services varies. This is partly because of the differences in their client populations, the psychiatric sectors care for more people with mental disabilities than medical-social services do (Chevreul et al. Reference Chevreul, Brigham, Durand-Zaleski and Hernández-Quevedo2015, table 5.3), and partly because of the competition between them. As a result, sectorization has remained, in the words of one influential government report, the “basic organizing principle” of psychiatry in France (Piel and Roelandt Reference Piel and Roelandt2001).

Sectorization helps to promote high levels of access to mental health care in France, where the utilization of psychiatric services is higher than in many of its peer societies, including Great Britain and Denmark (DGC 2014). But even within France, mental health care is considered more accessible than other forms of health care. The major government agency for health statistics (the Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques, or DREES) rates access to psychiatrists higher than access to pediatricians. In urban areas, psychiatrists are more accessible than ophthalmologists and gynecologists (Castell and Dennevault Reference Castell and Dennevault2017).

These supply and access outcomes, too, are the product of public policy. As Chapter 5 will show, the sectorization system grew out of a small community care program that eventually gained long-term financial support from the general health system. Today, French health insurance funds (financed by employment contributions and other revenues) entitle all residents to a basket of preapproved health care services, including psychiatric services (Mossialos et al. Reference Mossialos, Djordjevic and Osborn2017). In general, services rendered at public institutions require an up-front payment of 20 euro, while private providers require more (at least 25 euro), but this difference is much wider in mental health care services: 15 euro for public providers and at least 39.70 euro for private providers. The funds then reimburse 70 percent of public sector fees and 30 percent of the negotiated private sector fees, but beneficiaries with chronic conditions such as mental illness qualify for full reimbursement of these fees. In short, these financial arrangements cover virtually all health costs for people with mental illness and incentivize the development of public psychiatric care.

Norway

Norway also provides high levels of mental health care. To understand why, it is crucial to understand its distinct financial and administrative infrastructure. The state often provides a substantial pot of separate public funding for mental health. A “Golden Rule” principle even stipulates that growth in mental health care must be greater than growth in general somatic health care (Romøren Reference Romøren, Hatland, Kuhnle and Romøren2018).Footnote 16 Norway has also implemented a system similar to French “sectorization.” Drawing on centralized general tax revenues, municipalities administer and pay for “district psychiatric centers,” public psychiatric outpatient care centers akin to the centres médico-psychologiques. They also pay for, manage, and integrate these services into the municipalities’ inpatient psychiatry. Regional health authorities pay other outpatient care (about half of the total supplied). These patterns produce some geographic variation in service supply; but unlike their counterparts in Sweden (or even the United States), Norwegian localities draw on far fewer local funds to provide care. Instead, they rely equally on funds distributed from the central government and must commit to providing a basic package of services in exchange for it. Although the vast majority of care is public, 12 percent is provided through private practitioners contracted by specialty hospitals (Sperre Suanes 2020). Moreover, children receiving care in the district psychiatric centers and their attendant hospitals have no payment. The same is true for adults who have reached the yearly user fee ceiling limit (about $240 USD, NOMESCO-NOSOSCO 2022; per Norges Bank 2023a).

The examples of France and Norway challenge the narrative that people with mental conditions have “nowhere to go” for care. Although that might be true in the United States and the other countries on the low end of the spectrum plotted in Figure 2.1, it is not true for all affluent democracies. In fact, and contrary to scholarly and popular presumptions of mental health, countries that supply high levels of mental health care provide both ample community care and ample inpatient care through the public sector. As noted, existing typologies of national public policy approaches cannot explain these differences. Moreover, the variation exists despite countries’ shared experience of psychiatric deinstitutionalization.

A comparative-historical analysis can test the hypothesis that the presence of a public labor–management coalition, enabled by independently organized and unified public managers, propelled the welfare workforce to expand mental health care in some countries (while absence of the welfare workforce reduced mental health care in others). Four cases, whose contemporary mental health systems have been discussed in this chapter, will serve as the testing ground for this hypothesis in the chapters that follow. Chapters 3–5 first assesses the hypothesis in the case of US deinstitutionalization, which most influenced global narratives about this process, against the contrasting experience in France. Chapter 3 structures the comparison by ensuring that the conditions that preceded deinstitutionalization were the same in both countries, save for the organization of their public psychiatric managers. Chapters 4 and 5 use within-case process-tracing techniques to show how this difference shaped the diverging trajectories of deinstitutionalization in the United States and France, respectively. Chapter 6 then assesses the extent to which the hypothesis can explain the supply of mental health care elsewhere (and account for lingering alternative hypotheses) by juxtaposing the cases of Sweden and Norway. Together, I leverage these four cases to demonstrate how the welfare workforce shaped the supply of mental health care across a variety of welfare state regimes, health system types, and time periods.

Coda: Deinstitutionalization Defined

Conceptualizing deinstitutionalization requires determining whether to use that term in the first place. In humanistic and social science theory, institutionalization most often refers to the normalizing, routinizing, or codifying of various aspects of social life. Meanwhile, in the empirical analysis of social policy, the term can apply to multiple areas, such as the historic deinstitutionalization of workers out of poorhouses, or of children out of orphanages, and even the institutionalization of the elderly into care homes.Footnote 17

Even among scholars of mental health, the term lacks universal acceptance. Critical scholars concerned with the evolution of social control techniques have opted for language with a stronger charge. The influential writings of Andrew Scull (Reference Scull1984, 1), for example, employ the term “decarceration” to refer to a broader “state-sponsored policy of closing down asylums, prisons, and reformatories.” At the same time, scholars writing about non-anglophone countries often find that this anti-institutional bias does not represent the experiences of other countries. Writing about the French experience, Henckes (Reference Henckes2009, 511–18) “questions the deinstitutionalization model as an explanation of transformations of the structure of the French psychiatry system in the postwar period,” noting that not all societies “call[ed] into question the psychiatric hospitals themselves.”

Nevertheless, the term “deinstitutionalization” remains the language of choice for many academics and journalists commenting on the psychiatric experience (e.g., Goodwin Reference Goodwin1997; Harcourt Reference Harcourt2011; Mechanic and Rochefort Reference Mechanic and Rochefort1990; Scheff Reference Scheff2014; Pan Reference Pan2013; Ford Reference Ford2015). Thus, while it is necessary to acknowledge the aforementioned limitations of the term, my focus on mental health policy prompts me to use this familiar and resonant language – two important criteria for concept formation (Gerring Reference Gerring1999).

Most analysts share an understanding that deinstitutionalization involves a shift in the primary locus of mental health services from one type of institution (namely, a mental hospital or asylum) to the community. What they mean by a “shift” and “community,” however, varies. The shift can involve either the reduction of the number of institutional residents or a reduction in the number of institutions themselves. Although I use the contemporary WHO definition of community-based care, the meaning of this term has evolved over time. When deinstitutionalization began to acquire political significance in the 1970s and 1980s, scholars began pointing to an increased reliance on “nontraditional” or “noninstitutional” mental health care facilities (Bachrach Reference Bachrach1983). Today, these facilities range from outpatient psychiatric centers, to nonmedical social services such as day care and vocational rehabilitation services, and even to housing facilities such as group homes and halfway houses. The varied meanings and usages of the term “deinstitutionalization” fail to provide a portable standard for comparison across countries.

Goertz’s (Reference Goertz2020) guidelines for concept formation can help to remedy this problem. At a “basic” level, degrees of institutionalization refer to whether the mentally ill in a given society are more or less likely to reside in an establishment that provides both psychiatric and custodial care. Deinstitutionalization, therefore, refers to a society’s movement down a continuum, in which the mentally ill become less likely to reside in these establishments than in the past. Three components of this definition, and the indicators used to measure them, warrant highlighting and discussion in greater detail: the psychiatric-custodial establishment, the length of residence, and the relative likelihood of residence. Table 2.1 offers a schematic guide to this overview.

Table 2.1 Schematic of the concept and measurement of “deinstitutionalization”

| Basic definition | A society’s movement down a continuum, in which the mentally ill become less likely to reside in an establishment that provides both psychiatric and custodial care than in the past | ||

| Dimensions | Prevalence of establishments that provide both psychiatric services and custodial care | The degree of permanence with which people with mental illness are institutionalized | Relative likelihood of residence in these establishments |

| Indicator example | Number of mental hospitals | Length of stay in mental hospitals | Proportion of residents in mental hospitals per 100,000 population in a given year, compared to a historical baseline (e.g., 1935) |

The presence or absence of the psychiatric-custodial establishment is perhaps the most visible marker of institutionalization. The decoupling of psychiatric and custodial care developed over the latter half of the 20th century, making these establishments appear obsolete to contemporary observers. While many specialized psychiatric hospitals still provide medical care, rarely do they serve a custodial function as well. Importantly, this dimension assumes that the society in question has a tradition of caring for the mentally ill in asylums. The repurposing or decline of the asylum constitutes this critical dimension of deinstitutionalization. To measure this dimension, the most obvious indicator is the number of establishments themselves; but looking only at the availability of mental hospitals says little about whether they serve a custodial function, in addition to a medical function. Substitute indicators, such as utilization rates (e.g., admissions) and capacity (e.g., beds) present the same problem, perhaps even more so, since these measures sometimes reflect the activity of both mental hospitals and the psychiatric wards of general hospitals.

Since these indicators do not convey very much information about how mental health care has changed within the hospital, the length of residence dimension attempts to capture changes in the function of the hospital, specifically regarding its custodial work. This component refers to the degree of permanence with which people with mental illnesses are institutionalized. Substitutable, constitutive indicators of this dimension include the average length of stay in a psychiatric institution and measures of long-term residents (sometimes called “inmates”). Note that inpatients can be distinct from residents. Inpatients can include those who stay in a mental hospital temporarily (even just one or two days), while residence connotes a long-term care arrangement.

Finally, the dimension of relative likelihood ties it all together. It shows that long-stay residence in the psychiatric-custodial establishment is changing over time. It captures, first, the likelihood that a person with mental illness resides in a mental hospital and, second, whether that person is any more or less likely to reside there today than in the past. It hence compares two populations (the institutionalized mentally ill to the noninstitutionalized mentally ill) and two time periods (the likelihood of institutionalization in one period in time to its likelihood in a previous period). Indicators of the effect of this phenomenon must capture the proportion of the population at a point in time that could be institutionalized, relative to a historical baseline. An ideal indicator is the percentage of residents living in mental hospitals, relative to those living in mental hospitals in 1935, well in advance of deinstitutionalization and just before the Second World War began. Setting the baseline during the war itself would have to account for war-induced population changes, particularly in the countries where the war was fought. The year 1935 offers a slightly more standardized baseline.

Measures of deinstitutionalization should consider the psychiatric needs of the population, too; but it is possible to presume that needs have been and continue to be similar across countries Moreover, epidemiologists have difficulty estimating these needs, in part because they are often partially (sometimes entirely) constructed, as sociologists have long emphasized (Durkheim Reference Durkheim1897; Parsons Reference Parsons1951; Scheff Reference Scheff1966). The evolving classification of psychiatric disorders make this patently clear (Bayer Reference Bayer1987; Grob Reference Grob1991; Kirk and Kutchins Reference Kirk and Kutchins1992; Mayes and Horwitz Reference Mayes and Horwitz2005). Yet most western societies have used and continue to use broadly similar diagnostic categories. For this reason, it is likely that social perceptions of psychiatric needs were parallel across countries at any given point in time. For example, the perceived mental health needs in France in 1950 were comparable to the perceived mental health needs in Belgium in 1950. Major international observers agree implicitly. As previously mentioned, the WHO has found that neuropsychiatric conditions account for about 30 percent of the global burden of disease in every western society, even though the provision of services for these conditions varies across those countries (WHO 2011).