I Introduction

Over recent decades, Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) has emerged as a key instrument to support evidence-based and coordinated policy-making.Footnote 1 After an early uptake in the US and the UK in the 1980s, RIA gained popularity and traction in developed economies in the second half of the 1990s. As a result, by 2015, all 34 members of the OECD at the time reported to have “some form of RIA” in place.Footnote 2

Following a trend originating in OECD countries, many developing and transition economies have also launched RIA programs, in particular to improve their investment climate. The last 15 years have seen support to emerging RIA systems becoming an increasingly important element of donors’ and international organisations’ development assistance. In particular, RIA has become part of a (regulatory) reform agenda oriented not only towards good governance and evidence-based decision making, but more so towards improving the business climate and competitiveness.Footnote 3

How have these reform efforts fared so far? What are the key design features of the RIA reforms enacted in developing countries? Have these reforms led to functioning RIA systems, ie systems whereby RIA documents are regularly produced and utilised in policy formulation? And, most importantly, if functioning RIA systems have not emerged out of RIA reforms, can we identify explanatory factors that led to this outcome?

Although several studies suggest mixed results,Footnote 4 there is no systematic account of RIA implementation in developing countries – as opposed to the abundance of periodic data produced by the OECD on developed countries. Existing studies suggest that global RIA diffusion has not led to the establishment of a single RIA model, and instead shows marked differences between countries. Additionally, many factors that can constrain the success of RIA reforms and the establishment of sustainable RIA systems have been identified, but these factors have not been systematised to facilitate explanatory analysis.

To fill this gap, two World Bank Group officials with many years of practical experience with supporting RIA reforms, with the support of an academic consultant, launched in 2016 a new study with the aim to come up with an overview of RIA reforms in developing countries, their design, success and challenges.Footnote 5

The study systematically and originally takes stock of the record of all the RIA reforms that occurred in developing countries in the period 2001–2016 and analyses a number of factors that impacted (mainly negatively) on the eventual roll-out of RIA systems in a selected sample of countries where the implementation of RIA reforms has proved more challenging. In other words, the 2018 World Bank study not only allows to take a much-needed snapshot of the state of the art of RIA reforms in developing countries as of 2016, but also, by looking at a number of representative case studies, to appraise in detail factors for success/failure of such reforms.

The present article is structured as follows. In Section II the research design of the 2018 World Bank study is briefly introduced. The results of the macro overview of RIA reforms in developing countries are presented and discussed in Section III. In Section IV we move from the macro picture to the micro setting of the four case studies (Botswana, Cambodia, Kenya and Uganda) to unearth which (and how) challenging RIA factors have emerged in reform practice. Section V concludes by looking at and discussing key findings and how they can help in mitigating “risks when reforming”.

II Research design

The 2018 World Bank study on which this article builds upon aims at answering five research questions:

(1) How many developing countries have launched RIA reforms?

(2) What are the main design features of RIA reforms in developing countries?

(3) Were the developing country RIA reforms successful or not?

(4) Can particular design features be associated with successful and unsuccessful RIA reforms?

(5) Can we identify key factors causing certain RIA reforms to be unsuccessful?

Given the global scope of the investigation and the scattered nature of the data, the team working on the study had to take several clear-cut methodological decisions to tackle the above puzzles. First of all, surveys were ruled out as unique means of collecting data points given the typically rather limited response rates, and problematic reliability, observed in those studies that solely resort to questionnaires sent to civil servants and/or country experts. The decision, hence, was to rely primarily on secondary sourcesFootnote 6 and triangulate them with additional data such as: existing surveys and databases (especially the World Bank Group’s Global RIA Database and Global Indicators of Regulatory GovernanceFootnote 7 ), contributions by in-country based World Bank staff, as well as expert validation by Word Bank Group staff which provided Technical Assistance in the implementation of RIA reforms. Information from World Bank staff was collected through a questionnaire, which covered a range of data points, including period implemented, the role of donors and international organisations, and other factors in the reform environment such as reforms that have overlapped with the RIA reforms. As field-based World Bank staff are in daily contact with counterparts across client governments, they are in a position to identify appropriate sources of information and gather high quality data as required.Footnote 8

As for the selection of the key reform design features to measure, the study draws on a template which is specific to developing countries.Footnote 9 This is because of the fact that, although the so-called OECD model has proven crucial in the global diffusion of RIA reforms and systems, developing countries admittedly approach RIA reforms with different aims, resources and capacities. The set of key reform design features measured in the study was therefore more limited with respect to the OECD best practice and checklists and reflects the specificities of regulatory reform in developing countries. As a result, the key dimensions of RIA reforms measured in the study are the following:

(1) presence of formal political commitment (for instance in a strategic/policy document);

(2) integration in rule-making process (integration of RIA in the policy cycle/policy formulation process through a legal provision);

(3) establishment of a coordination/oversight body/authority;

(4) availability of RIA guidelines and methodologies;

(5) presence of consultation mechanisms;

(6) capacity-building activities and early practice/piloting of RIA.

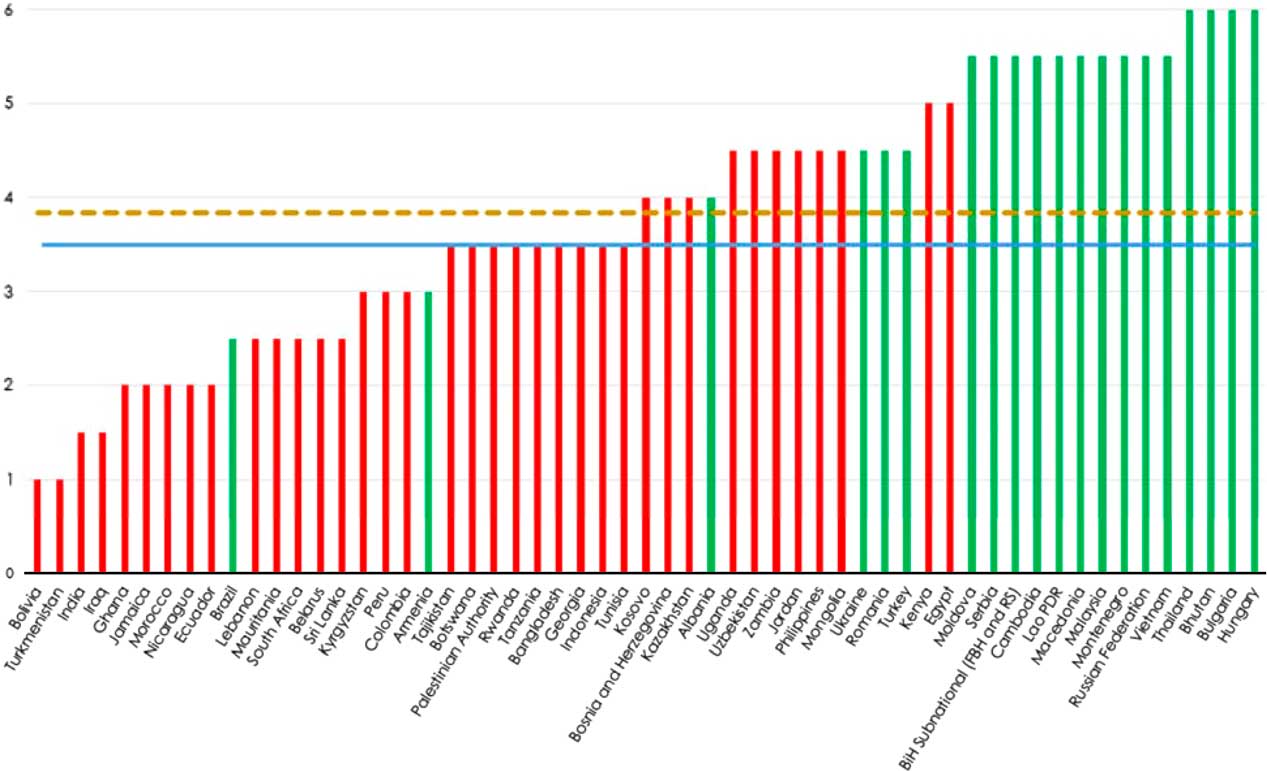

Each of these dimensions, in each of the developing countries which launched a RIA reform in the period 2000–2016, was measured according to a simple scoring scheme capturing full (1 point), partial (0.5 points) or lack (0 points) of compliance with the above “good practice” RIA standards. The end-result is a synthetic composite indicator (ranging from 0 to 6) measuring the adherence of each RIA reform to the simple set of good practices which are especially relevant for developing countries (see Table 1 and Figure 1 below).Footnote 10

Table 1 Reforms modalities and resulting RIA systems in the 60 developing countries where RIA reforms have been identified as having taken place in the 2001–2016 period

Figure 1 Design scores for RIA reforms which have been concluded for more than two years (N=57). The composite indicator spans from 0 to 6. Reforms scored below the 3.5 threshold (continuous horizontal line) were considered as not fully adhering to good international practices, and vice versa. The dotted horizontal line indicates the mean reforms’ score for the universe (mean=3.8). Light grey columns illustrate reforms that led to a functioning RIA system; dark grey columns show reforms that did not lead to a functioning RIA system.

The challenge to determine what constitutes a “functioning” RIA system, and by when such functionality could be expected after the launch of a reform project, was solved by establishing a simple and easily operationalisable threshold criterion to adjudicate whether a country has effectively a (minimally) functioning RIA system in place: the existence of publicly availableFootnote 11 RIA documents drafted by national officials at least two years after launch of the RIA reform. RIA reforms which have been launched within the last two years were counted as “too early to call”, regardless of whether these RIA systems were actively producing RIAs or not.Footnote 12

To grasp the correlation between reform design and successful implementation the synthetic composite indicator presented above is used. The threshold for a reform to be sufficiently well designed is set to 3.5 points out of 6 and individual country scores are then contrasted to the existence, or lack thereof, of a functioning RIA system.

Finally, the study explores why some RIA reforms, despite having “ticked all the boxes” of good practice design, had not (yet) delivered sustainable RIA systems. The purpose of this part of the study is to articulate factors for implementation challenges within a structured analytical framework, ie a theoretical causal mechanism (composed of interrelated causal factors) that can be subject to empirical qualitative testing in the context of case studies. To some extent, these factors consolidate “popular” explanations shared among RIA advocates, practitioners and scholar, which have never been systematically tested. They are:

(i) crowding out: competing short-term reforms seen as low hanging fruits for the political principals can crowd out more time-consuming and challenging RIA reforms. For instance, one-off deregulatory and red tape reduction efforts may require less political capital, ensure more visible and faster results and hence “crowd RIA out”;

(ii) insufficient adaptation or “Plug and Play”: this is an oft-voiced criticism: the model of RIA system transferred to developing countries involve too little adaptation of so-called “OECD best practices”. Such best practices might be unsuitable and unrealistic in developing countries. For instance, establishing a fully independent body for RIA coordination may paralyse, delay, or even halt the reform process;

(iii) misunderstanding of reform requirements or “Pig-in-a-poke”: domestic reform champions may have insufficient understanding of RIA as a long-term governance reform that needs broad stakeholder buy-in. An implementing government may have a basic understanding and ownership of regulatory reform concepts and RIA, but may be unaware of resources required to successfully introduce a RIA system, including the political capital investments and political risks required. This may result in the failure to allocate adequate resources, or to put in place sufficiently empowered institutions;

(iv) resistance from public officials: RIA systems in developing countries may also be difficult to implement because of lack of commitment among civil servants. Unelected civil servants can resist/oppose reform even when there is a binding requirement explicitly mandating RIA in policy formulation. Public officials may resist RIA systems simply because they can change established processes and work patterns, but also because the associated transparency may expose practices which are not ethical or legal;

(v) impatient donors leading to overly short time-frames for reform: development partners supporting RIA reforms may have an overly optimistic view about the time it takes for an RIA system to develop and become sustainable. Consequently, too early withdrawal of financial and technical support may lead to the breakdown of RIA reforms, which may have survived with a slightly longer implementation support from development partners;

(vi) “unhinged”: ie RIA reforms not linked to or leveraged by other public sector reforms. RIA reforms face implementation challenges because they are developed and implemented in a vacuum, without adequate linkage to other supportive good governance instruments and practices.

It was not expected that any of the factors above by themselves would be able to fully explain why a particular RIA reform did not deliver on its goals. Consequently, the study attempts to capture the dynamic of these factors in the RIA reform context through the country case studies.

III Global overview

Although limited to 2016 and with some reforms still underway by that time, the 2018 study reveals that 60 developing countries have embarked in RIA reforms since 2000 (see Table 1 and Figure 1 below). Crucially, all of these reforms have been backed by an international organisation, whether acting as donor and/or as provider of technical assistance. In three of the surveyed countries (5%), RIA reforms were within the first two years of implementation, and hence “too early to call”. These reforms are left out from the analysis of whether the reforms were successful or not.

Out of the 57 governments having initiated RIA reforms more than two year before 2016, 20 (35%) of the RIA systems are functional and operational, whereas 37 (65%) have not succeeded in establishing an operational RIA system. As hinted in the previous section, the criterion for defining a RIA system as functional and operational is that two years after the RIA reform began, Regulatory Impact Statements or documents are regularly produced and available in the public domain.

Countries’ scores on the “RIA Reform Index” vary in a largely expected pattern (see Table 1 and Figure 1 below). The mean score across all 60 countries is 3.8. For the 20 RIA systems which are functional and operational, the average RIA reform score is 5.1. The average RIA reform score for the sample of 37 reforms that did not lead to functioning RIA systems is 3.2. In 22 (37%) of the surveyed countries, the score assigned to RIA reforms is below 3.5, hence they can be considered as not complete and/or adequately designed.

Although there is strong correlation between adherence to “good practices” and successful RIA reforms (ie RIA reforms which did not observe good practices, typically, did not lead to a functional RIA system)Footnote 13 compliance with appropriate reform design and practices is a necessary but not sufficient predictor/condition of success. A large number of RIA reforms (20) which did not succeed, did in fact observe and comply with good practices.Footnote 14

Some good practices appear more important than others. The study compared performing RIA systems with non-performing RIA systems along the six sub-dimensions comprising the “RIA Design Index”. By far the biggest differentiator was adherence to two particular RIA design features, namely the establishment of an oversight body, and the formal integration of RIA procedures in the policy-making process. This seems to suggest that RIA reforms, which do not include institutional leadership/oversight, and which do not formally “wire” RIA requirements into the policy-making process, have a higher likelihood of not taking off than reforms that do observe these practices. While this is hardly surprising to experts and advocates for RIA reforms, this finding provides further empirical evidence to the claim. The data also suggest that the relative importance of formal political commitment (ie a policy statement about commitment to establish a RIA system) as well as capacity-building measures are of less importance than other building blocks of a successful RIA system, ie they seem to make no decisive difference in terms of the success of the reform. These findings could have implications for the sequencing and relative emphasis of the various design components of a RIA system.

IV Case studies

In this section we briefly elaborate on why a subset of the “well-designed” RIA reforms did not lead to operational RIA system. The findings reported and discussed hereafter stem from having process traced four RIA reform processes as case studies. The analysed reforms took place in Botswana, Cambodia, Kenya and Uganda.

For reasons of space it is not possible to take stock of each of the cases in this article. We refer the interested readers to the 2018 World Bank study for more details on the employed methodology, causal mechanisms and case-specific findings. Table 2 synthetises the key findings and conclusions arisen out of the case studies in relation to the six challenging RIA factors presented in the previous section.

Table 2 Summary of reform period, design, status and challenging factors for countries selected for case studies

Looking at the cases jointly, it seems clear that all six factors play important roles in explaining why RIA reforms not always lead to operational RIA systems: Crowding out, insufficient adaptation, misunderstanding of reform requirements, resistance from vested interests, short time horizons for implementation, and limited linkages to other governance systems all seem relevant and often powerful contributors to why RIA reforms do not always develop as intended. It also seems that these factors are closely connected and mutually reinforcing each other.

A second observation relates to political leadership and institutional anchoring of RIA reforms. The initial rationale and impetus to pursue RIA reform is often closely linked to preceding or parallel regulatory burden reduction reforms. This close connection is very legitimate and in most cases probably strategically sound. However, it also comes with a risk of the RIA reforms being crowded out (factor i) by faster and more tangible reforms, and, perhaps more importantly, of being “stuck” with reform champions who are not capable or willing to pursue the cross-ministerial coordination and enforcement roles associated with a functioning RIA system. The “crowding out” factor seems closely associated with an insufficient appreciation by RIA reform champions of the requirements and long-term nature of RIA reforms (factor ii). The limited appreciation of RIA reform requirements may in part be due to insufficient clarifications made by external experts and developing partners.

Across all of the case studies there seemed to be no or only limited integration of RIA with, or linkage to, other public sector reforms. Instead, RIA reforms are often developed and implemented in a virtual vacuum, without adequate linkage to other supportive “good governance” practices and instruments such as, for example, performance management, strategic planning, or freedom of information laws. It seems likely that the relative disconnect of RIA systems from other governance systems had a negative impact on the reforms’ sustainability and capacity to evolve according to changing circumstances.

In fact, evidence from Western countries suggest that policy instruments like RIA work at their best when they are adopted and deployed in conjunction with other procedures which allow, taken together, for a greater involvement of the stakeholders in the policy process, overall transparency and accountability. Although the study could not test the effects of the interaction between different regulatory reform tools in the surveyed developing countries, it seems plausible to argue that such an ecological perspective on policy instruments seem to be of even greater importance for countries which have more limited administrative capacity, institutional endowment and tradition of substantive engagement of stakeholders in the policy (formulation) process.

V Lessons for RIA reformers

This article has reported on the key findings of the 2018 World Bank study which has provided one of the first comprehensive overviews of RIA reforms in developing and transition countries. Over the period 2001–2016, at least 60 developing countries have initiated RIA reforms, all of which have been supported by development partners in one way or another. Of the 60 reforms, three have been launched within the last two years and were not considered in the subsequent analysis.

Looking at the 57 RIA reforms that were initiated more than two years ago and applying a very simple “dead or alive” criterion (are RIA statements regularly produced and publicly available two years after the reform’s launch, or not?) the mapping of reforms found that 20 RIA reforms have led to operational and functional RIA systems, whereas 37 have not. Whether a “success-to-failure” rate of 1:2 after only two years is satisfactory, mediocre or poor depends on one’s perspective. If such appraisal is informed by an assumption about RIA reforms as relatively simple and linear, the judgement call is likely to be negative. However, if RIA reforms are considered a relatively complex governance reform requiring a difficult combination of long-term political commitment, coordination across government, technical skills, and willingness to rearrange decision-making processes, the success rate may be very acceptable, possibly even encouraging. Add to this that many RIA reforms which have not yet become operational and systematically applied may do so over a longer time horizon.

The study confirmed that RIA reforms designed in line with generally recognised “good practices” for developing and transition economies are more likely to lead to operational RIA systems than RIA reforms which were not. The single biggest difference between RIA reforms which led to operational systems, and reforms which did not, was formal/legal integration of RIA requirements in the policy-making process. In other words, formal/legal requirements for policy-makers to comply with RIA quality-assurance mechanisms, although not necessarily a guarantee for the quality of RIAs, may be the single-most important milestone towards establishing an operational RIA system. However, appropriate reform design was not found to a sufficient condition for successful RIA systems’ roll-out as a number of countries who ticked all the boxes in term of “good reform standards” still struggled to implement a functioning RIA system.

Drawing on this finding, the study sought to pin down what challenging RIA factors, beyond incomplete reform design, have contributed the most to non-functional RIA systems. This further layer of analysis allowed us to single out a number of policy implications and recommendations to transition and developing countries considering to establish a RIA system, and to development partners supporting such efforts. We point to five areas where changes to the strategic framing of RIA initiatives, compared with how most RIA reforms are developed today, may have the most significant impact:

(i) recast RIA as part of a long-term plan to improve regulatory quality and evidence-based rulemaking (not just burden reduction for businesses): because of regulatory reforms’ close relation to the investment climate, RIA is often launched in the context of regulatory burden reduction reforms. However, evidence-based policy making seen as a simple add-on to business licensing or other one-off reforms may create wrong perceptions about reform requirements and may embed RIA in suboptimal institutional structures;

(ii) use high-level political support to lock in the RIA reform at an early stage: the findings of this study suggest that there may be merit in capitalising on the strong political commitment often enjoyed at the early stages of RIA reform by seeking a formal/legal integration of RIA in the policy-making process. Legal amendments could be made such that they would only come into force with a certain delay (ie 12–18 months), but they would send a credible signal and navigation point for relevant stakeholders;

(iii) establish regulatory oversight bodies to champion RIA reform; functions may initially be focused more on guidance and support than gate-keeping: as could be seen in the macro overview of RIA reforms, the presence of an institutional structure that spearheads the reform efforts is a strong predictor of success. A formal structure can help manifest the government’s long-term commitment to RIA, both to internal and external stakeholders. A centralised body can manage roll-out across government and collect and disseminate knowledge over time. A strong gatekeeper function with authority to the oversight unit to “review and reject” RIAs of suboptimal quality may create unproductive adversarial relations between RIA stakeholders and may lead to speculative behaviour aimed at avoiding such scrutiny;

(iv) leverage other public-sector reform tools to promote evidence-based rule-making: RIA should not be considered an activity separate from other dimensions of the policy-making process. Efforts should be made to make evidence-based policy making part of the regular government functioning already at an early stage of the reforms. This includes communicating synergies and exchange of information with other functions, such as regulatory enforcement and strategic planning, but also formal integration in the government’s consultation practices and training curriculum;

(v) focus capacity-building efforts on clear targets and on-the-job requirements: findings of the study suggest that training and capacity building measures are not a predictor of a RIA reform’s outcome. The suggestion is that investments in RIA training may often provide only limited direct returns to the reform efforts. The implication for RIA reform may be that training at the early stages of RIA reforms should focus less on broad and generic RIA training, but rather be targeted to specific RIA requirements of the country.